Abstract

Objective

To translate the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) which is a self-administered questionnaire that assesses effect of dysphagia on the quality of life for patients with head and neck cancer, into Korean and to verify the validity and reliability of the Korean version of MDADI.

Methods

We performed 6 steps for the cross-cultural adaptation which consisted of translation, synthesis, back translation, review by an expert committee, cognitive debriefing, and final proof reading. A total of 34 dysphagia patients with head and neck cancers from Seoul National University Hospital answered the translated version of the questionnaire for the pre-testing. The patients answered the same questionnaire 2 weeks later to verify the test-retest reliability.

Results

One patient was excluded at second survey because he changed his feeding strategy. Overall, 33 patients completed the study. Linguistic validations were achieved by each step of cross-cultural adaptation. We gathered statistically strong construct validity (Spearman rho for subdomain scores to total score correlation range from 0.852 to 0.927), internal consistency for subdomains (Cronbach's alpha coefficients range from 0.785 to 0.889) and test-retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient range from 0.820 to 0.955)

Conclusion

The Korean version of the MDADI achieved linguistic validations and demonstrated good construct validity and reliability. It can be a useful tool for screening and treatment planning for the dysphagia of patients with head and neck cancers.

Keywords: Quality of life, Deglutition disorders, Head and neck neoplasm, Questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

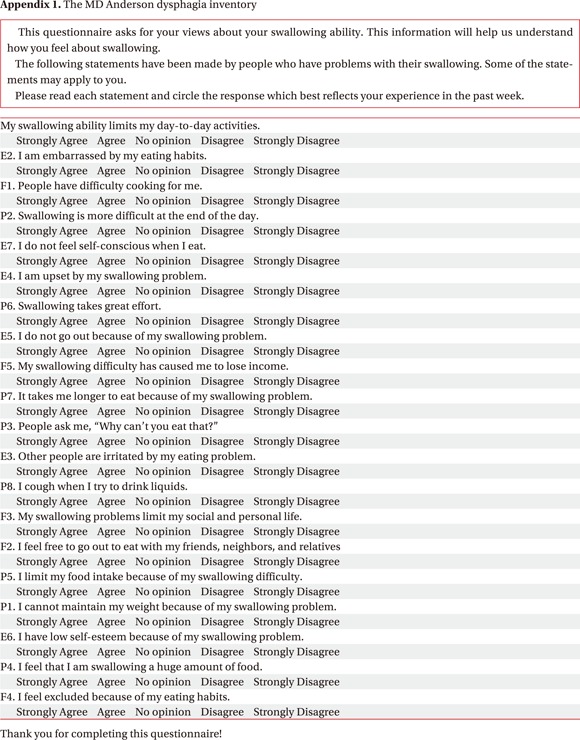

The absolute number of head and neck cancer survivors is expected to increase as the treatment outcome improves [1,2], although there is considerable variability in reported frequency worldwide [3]. The improved treatment outcome in nasopharyngeal cancer by concurrent chemoradiation therapy is case in point [4,5]. Therefore, the interest in health-related quality of life (QOL) of cancer survivors is increasing. The previous study reported that dysphagia of head and neck cancer patients degrades the health-related QOL [6-8] which has increased demands for dysphagia-specific health-related QOL measurement tools. In this regard such tools are being developed and used around the world [9-11]. However, there is no standardized Korean tools for measuring dysphagia-specific health-related QOL. The MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) developed by Chen et al. [12] is the dysphagia-specific health-related QOL measurement tool for head and neck cancer patients. The MDADI contains 20 questions covering four subdomains (Appendix 1). In addition, it has been used in many studies due to high validity and reliability [12].

The purpose of this study was to provide the academic basis of the Korean version of MDADI (K-MDADI) with the linguistic validation [13-18], construct validity, and reliability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

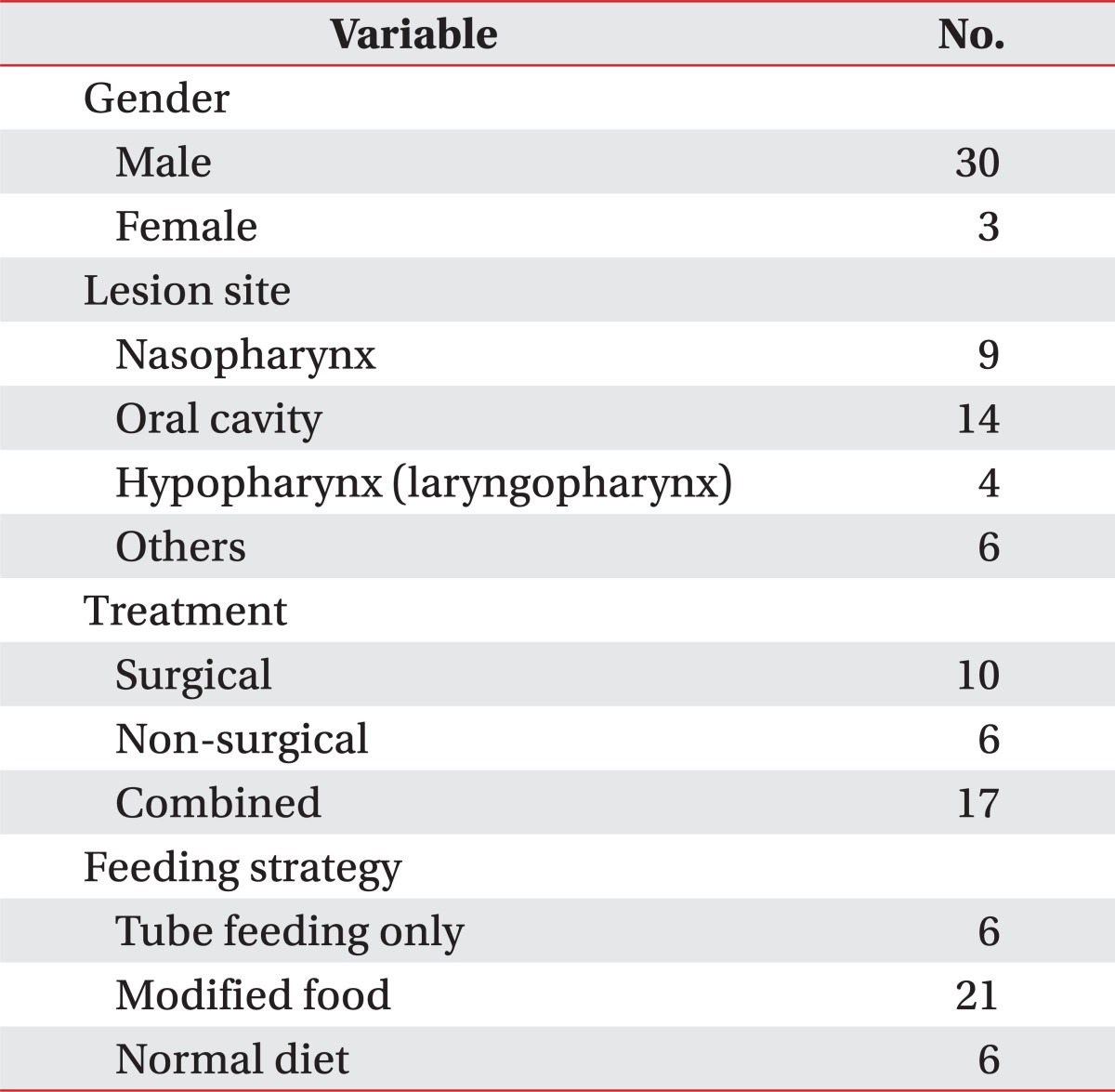

The survey was performed with the 34 volunteers (31 males, 3 females) who had head and neck cancers. They were asked to fill out the final version of K-MDADI and took videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) on the same day. The mean age of patients was 61.18 years (range, 37-79 years) and the average duration of dysphagia was 59.38 months (range, 3-252 months). The cancer lesion, treatment method, and current diet are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects

MDADI

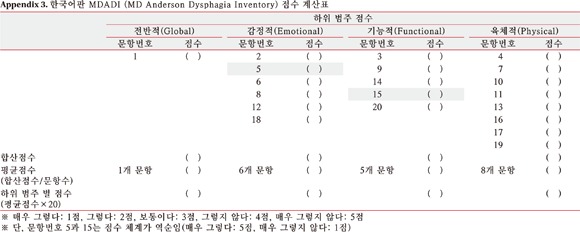

MDADI is a free questionnaire developed by Chen et al. [12] to evaluate the dysphasia-specific health-related QOL for head and neck cancer patients. The survey contains 20 self-administered questions to measure 4 subdomains of global (1 question), emotional (6 questions), functional (5 questions), and physical category (8 questions). Each question was composed of Likert scale and expressed as from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). But it was expressed in inverse order for two questions: Question 5. I do not feel self-conscious when I eat; Question 15. I feel free to go out to eat with my friends, neighbors, and relatives. The average score for each question of subdomain was multiplied by 20 to calculate subdomain score. Higher scores meant better dysphagia-specific health-related QOL.

Translation of the survey

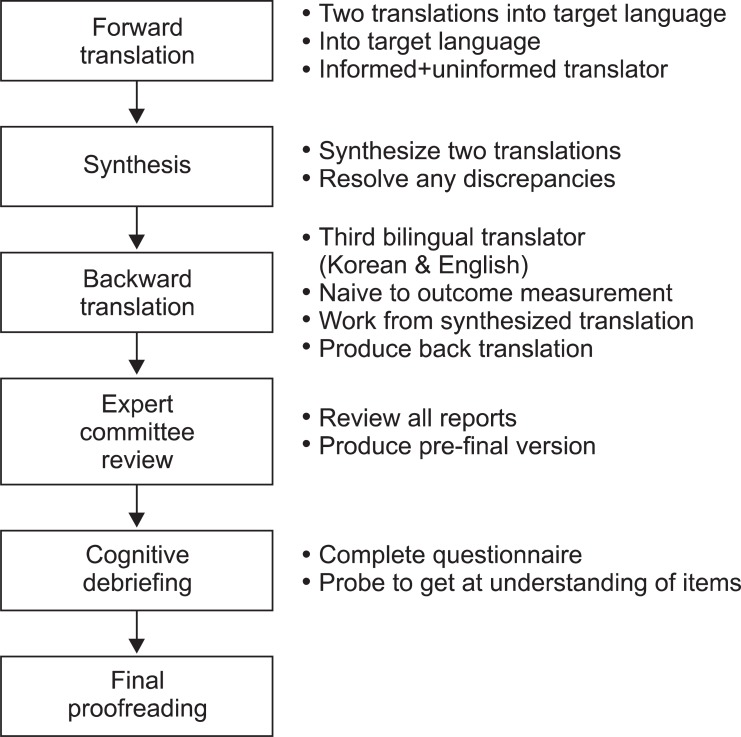

The translation consisted of the following (Fig. 1) according to the cross cultural adaptation method [19,20].

Fig. 1.

Process of cross-cultural adaptation.

Forward translation: In order to develop the K-MDADI, the translation was performed with the authorization from original author of MDADI, Chen AY. Two translators who are proficient at both English and Korean participated; one translating with preliminary knowledge of MDADI and the other with no medical background.

Synthesis of the translations: Two translations were synthesized into one interim version through the discussion between authors and translators.

Backward translation: The interim version was translated into English again by a 3rd translator who was bilingual in English and Korean with no medical background. Thereafter, the difference of backward translation from concept of the original survey was verified by three professionals composed of rehabilitation medicine doctors who were fluent in both English and Korean, and have treated dysphasia patients for over two years.

Review of expert committee: The authors and translators gathered again to check any potential errors.

Cognitive debriefing: The preliminary examination was performed on 5 head and neck cancer patients with the translated MDADI before finalization of translation. The understanding and answering of questions without any help were verified and the opinions on the ambiguity, misunderstanding, awkward expression, and cultural differences were collected through in-depth interviews.

The final proof-reading: The development of the K-MDADI was completed after inspecting the survey style and typing error.

Validation of the final version

The head and neck cancer patients with dysphasia were surveyed on the same day of VFSS. The survey was self-administered and performed again two weeks after the initial survey for verifications of reliability whether there had been changes of the general condition and feeding strategy was checked on the second survey.

Swallowing function

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association National Outcome Measurement System (ASHA-NOMS) was determined after VFSS [21]. The correlation between measured ASHA-NOMS score and K-MDADI score was analyzed.

Data analysis

The linguistic validation of K-MDADI was verified by the cross cultural adaptation method [13-20]. The SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The correlation coefficient was used to measure the construct validity of K-MDADI [14,15,22]. The four subdomains were defined as the construct and the Spearman rho was calculated between subdomain scores and total scores to check whether the test scores well measured the defined constructs. The Cronbach's alpha was calculated for internal consistency of subdomains [23] and intra-class correlation coefficient was obtained for test-retest reliability [24]. The correlation between ASHA-NOMS score and total score of the K-MDADI was checked by Spearman rho.

RESULTS

K-MDADI

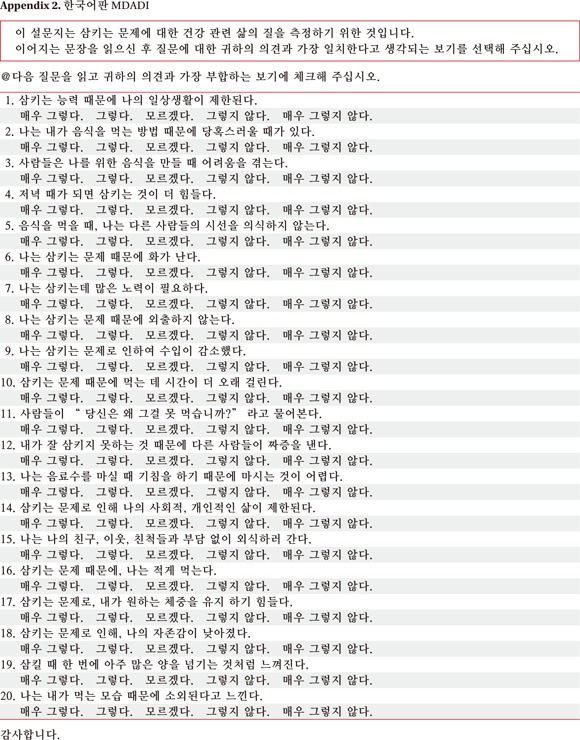

A total of 20 questions were translated and validated by the cross cultural adaptation method (Appendix 2). The order of each question was same as the original and questions were sequentially numbered. The table for scoring was attached at the end of K-MDADI (Appendix 3).

Validity and reliability of K-MDADI

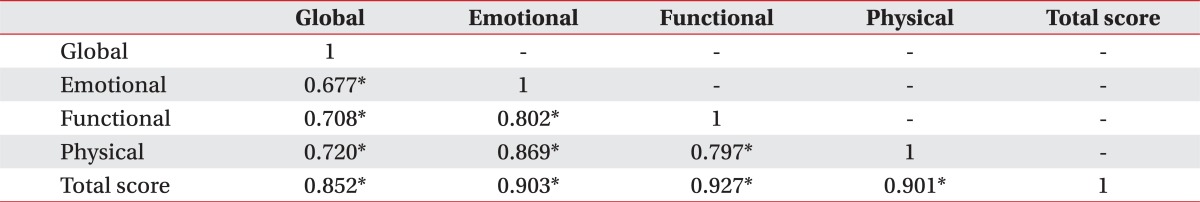

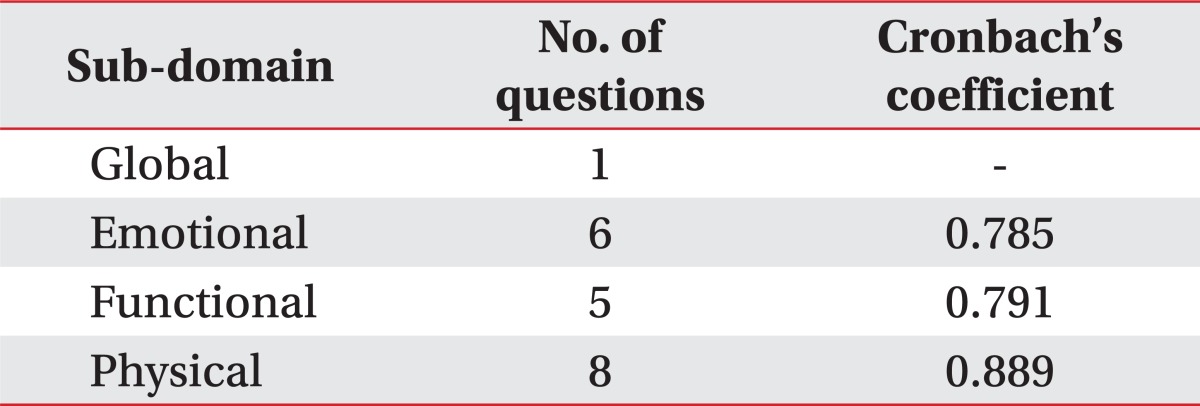

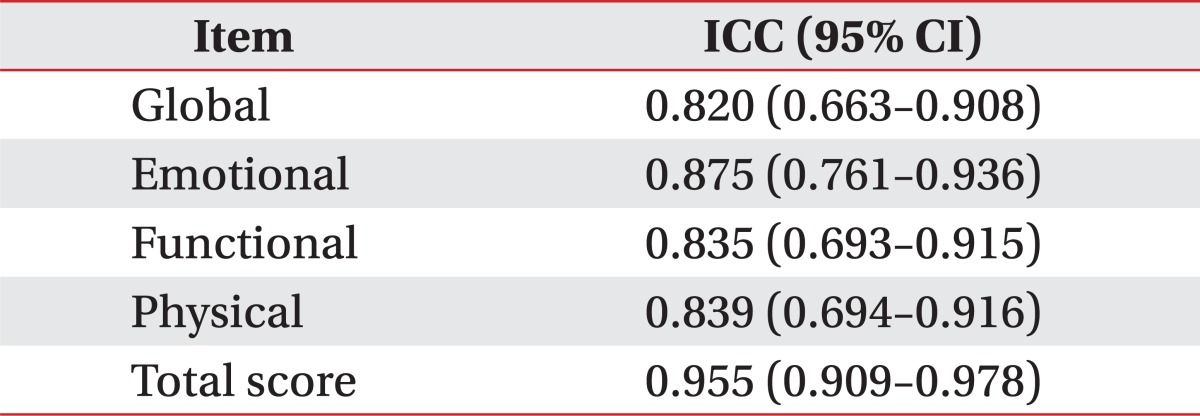

Overall 33 patients were included, because one patient changed diet strategy after initial VFSS. Construct validity was checked by Spearman rho. The Spearman rho between subdomain scores and total score of K-MDADI ranged from 0.852 to 0.927 (Table 2). The Spearman rho between each subdomain scores ranged from 0.677 to 0.869. The internal consistency was checked by Cronbach's alpha in three subdomains except the global subdomain which has only one question. Cronbach's alpha ranged from 0.785 to 0.889 (Table 3). The intra-class correlation coefficient of each subdomains and total score by test-retest method ranged 0.820 to 0.955 (Table 4).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of overall scores and subdomain scores of the Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory

*p<0.05.

Table 3.

Internal consistency of the Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory

Table 4.

Test-retest reliability of Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory by ICC

ICC, intra-class correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

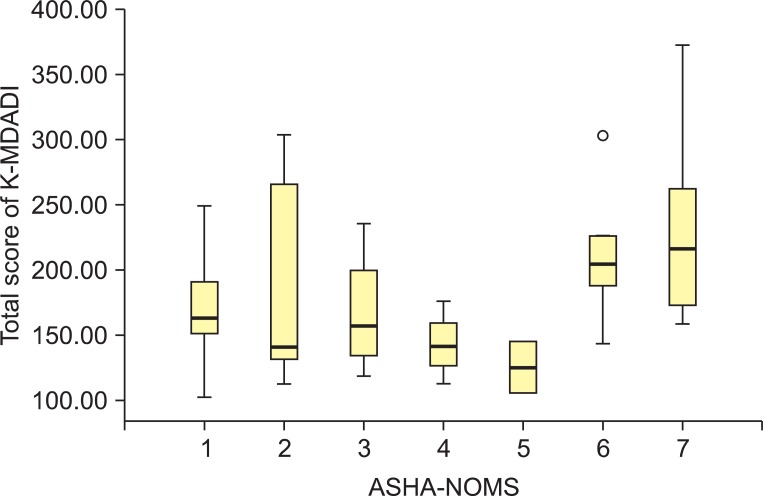

Swallowing function and K-MDADI

The ASHA-NOMS [21] score and total score of K-MDADI showed no significant correlation (Fig. 2). The Spearman rho of total score of K-MDADI and ASHA-NOMS score was 0.282 (p=0.112).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of total score of Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (K-MDADI) according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association National Outcome Measurement System (ASHA-NOMS) score.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to develop the K-MDADI and to verify its validity and reliability. The linguistic validation of K-MDADI was checked by the cross cultural adaptation method [13-20] and the construct validity and reliability was evaluated statistically.

The process of cross cultural adaptation caused little difficulty because MDADI had relatively simple and clear sentences. However, question 13 was modified because patients who could not drink water were unable to answer the question.

The patient's cooperation is very important for diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia. But the previous research reported various compliance of dysphasia diet with modified consistency [25-27]. Patients' perceived QOL is as an important determinant for higher compliance as objective functional evaluation such as VFSS. The study actually showed no statistical correlation between total score of K-MDADI and ASHA-NOMS score [21], and it means that the functional state only cannot fully explain the QOL of dysphagia patients. The previous study showed correlations between MDADI and performance status scale for dysphagia [28], but correlation with MDADI emotional domain than with other domains. It implied that self-administered MDADI reflects the subjective emotional condition of patients better than the performance status scale scored by clinicians [12]. Meanwhile, other study showed that depression was correlated with dysphasia for head and neck cancer patients, and low QOL was more highly correlated with depression rather than with severity of dysphasia [29]. Depression might aggravate treatment compliances, subjective pain, and suicidal risk. Therefore dysphagia-specific QOL as well as dysphasia function should be evaluated in the treatment of dysphasia [30].

MDADI is a dysphagia-specific QOL measuring tool for head and neck cancer patients and has been used widely and translated in many languages [31-33]. In addition, MDADI could be applicable to not only head and neck cancer patients but also stroke patients [32,34].

The limitations of this study lies in that we could not check the concurrent validity due to lack of another Korean version of dysphagia-specific QOL measurement tool and that the study had relatively small sample size although statistical analysis was possible. It was also limitation of this study that we did not evaluate depression. But in case of translation for other dysphasia-specific QOL measurement tool in the future, concurrent validity could be provided using the above-stated K-MDADI.

In this study we translated MDADI into Korean by cross cultural adaptation method for clinical purpose. And we also checked the validity and reliability of the K-MDADI for providing academic basis for medical research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciated Dr. Chen's kind permission to translate MDADI into Korean. We would like to thank Minsoo Ha, Saena Sohn, and Hyunkyung Kwon for their contribution to the translation.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:11–24. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KM, Kim YM, Shim YS, Kim KH, Chang HS, Choi JO, et al. Epidemiologic survey of head and neck cancers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:80–87. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sankaranarayanan R, Masuyer E, Swaminathan R, Ferlay J, Whelan S. Head and neck cancer: a global perspective on epidemiology and prognosis. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:4779–4786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fountzilas G, Tolis C, Kalogera-Fountzila A, Karanikiotis C, Bai M, Misailidou D, et al. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin, epirubicin, and paclitaxel (CEP), followed by concomitant radiotherapy and weekly paclitaxel for the management of locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group phase II study. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin S, Tham IW, Pan J, Han L, Chen Q, Lu JJ. Combined high-dose radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy improves survival in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:474–479. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31821a9452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell SJ, Wong HB, Loh KS, Ngo RY, Wilson JA. Impact of dysphagia on quality-of-life in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2005;27:864–872. doi: 10.1002/hed.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen NP, Frank C, Moltz CC, Vos P, Smith HJ, Karlsson U, et al. Impact of dysphagia on quality of life after treatment of head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Peris P, Paron L, Velasco C, de la Cuerda C, Camblor M, Breton I, et al. Long-term prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: impact on quality of life. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, Rosenbek JC, Robbins J, Chignell KA, et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I. Conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia. 2000;15:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s004550010012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woisard V, Andrieux MP, Puech M. Validation of a self-assessment questionnaire for swallowing disorders (Deglutition Handicap Index) Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2006;127:315–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, Pryor JC, Postma GN, Allen J, et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, Hebert T, Leyk S, Lewin J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Kim E, Oh SJ, Lee BS, Kim DA. The linguistic validation and reliability of the Korean version 'Qualiveen Questionnaire'. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2010;34:524–543. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins MM, O'Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Pontari MA, Adler A, Eremenco S, et al. The Spanish National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index: translation and linguistic validation. J Urol. 2001;166:1800–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh SJ, Park HG, Paick SH, Park WH, Choo MS. Translation and linguistic validation of Korean version of the King's Health Questionnaire Instrument. Korean J Urol. 2005;46:438–450. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homma Y, Tsukamoto T, Yasuda K, Ozono S, Yoshida M, Shinji M. Linguistic validation of Japanese version of International Prostate Symptom Score and BPH impact index. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;93:669–680. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.93.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quittner AL, Sweeny S, Watrous M, Munzenberger P, Bearss K, Gibson Nitza A, et al. Translation and linguistic validation of a disease-specific quality of life measure for cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:403–414. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. National Outcomes Measurement System (NOMS) Rockville: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; 1998. Adult Speech-Language pathology training manual. [Google Scholar]

- 22.CronbacH LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull. 1955;52:281–302. doi: 10.1037/h0040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low J, Wyles C, Wilkinson T, Sainsbury R. The effect of compliance on clinical outcomes for patients with dysphagia on videofluoroscopy. Dysphagia. 2001;16:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s004550011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenvinge SK, Starke ID. Improving care for patients with dysphagia. Age Ageing. 2005;34:587–593. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford H, Leslie P, Drinnan MJ. Compliance with dysphagia recommendations by carers of adults with intellectual impairment. Dysphagia. 2007;22:326–334. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<564::aid-cncr2820660326>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin BM, Starmer HM, Gourin CG. The relationship between depressive symptoms, quality of life, and swallowing function in head and neck cancer patients 1 year after definitive therapy. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1518–1525. doi: 10.1002/lary.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Leeuw JR, de Graeff A, Ros WJ, Blijham GH, Hordijk GJ, Winnubst JA. Prediction of depressive symptomatology after treatment of head and neck cancer: the influence of pre-treatment physical and depressive symptoms, coping, and social support. Head Neck. 2000;22:799–807. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<799::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speyer R, Heijnen BJ, Baijens LW, Vrijenhoef FH, Otters EF, Roodenburg N, et al. Quality of life in oncological patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: validity and reliability of the Dutch version of the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory and the Deglutition Handicap Index. Dysphagia. 2011;26:407–414. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9327-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlsson S, Ryden A, Rudberg I, Bove M, Bergquist H, Finizia C. Validation of the Swedish M. D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck cancer and neurologic swallowing disturbances. Dysphagia. 2012;27:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guedes RL, Angelis EC, Chen AY, Kowalski LP, Vartanian JG. Validation and application of the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory in patients treated for head and neck cancer in Brazil. Dysphagia. 2013;28:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s00455-012-9409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen PH, Golub JS, Hapner ER, Johns MM., 3rd Prevalence of perceived dysphagia and quality-of-life impairment in a geriatric population. Dysphagia. 2009;24:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]