Abstract

Venous dysfunction has recently been hypothesized to contribute to the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis (MS). 2D phase-contrast (PC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive and innocuous technique enabling reliable quantification of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood flows in the same imaging session. We compared PC-MRI measurements of CSF, arterial and venous flows in MS patients to those from a normative cohort of healthy controls (HC). Nineteen MS patients underwent a standardized MR protocol for cerebral examination on a 3T system including Fast cine PC-MRI sequences with peripheral gating in four acquisition planes. Quantitative data were processed using a homemade software to extract CSF and blood flow regions of interest, animate flows, and calculate cervical and intracranial vascular flow curves during the cardiac cycle (CC). Results were compared with values obtained in 21 HC using multivariate analysis. Venous flow patterns were comparable in both groups without signs of reflux. Arterial flows (P=0.02) and cervical CSF dynamic oscillations (P=0.01) were decreased in MS patients. No significant differences in venous cerebral and cervical outflows were observed between groups, thereby contradicting the recently proposed theory of venous insufficiency. Unexpected decrease in arterial perfusion in MS patients warrants further correlation to volumetric measurements of the brain.

Keywords: cerebral blood flow measurement, cerebrospinal fluid, cerebral hemodynamics, MRI, multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disorder affecting the central nervous system, presumed to have an autoimmune pathogenesis. Although the triggering factors remain partially unknown, it is now widely admitted that they mainly involve genetic and environmental factors.

Recently, a new concept was brought in by Zamboni et al.1, 2 suggesting that MS is provoked by venous dysfunction, at both intracranial and extracranial levels. Congenital venous stenoses, at different cervical and/or thoracolumbar levels, are presumed to induce abnormal, insufficient, or even reversed venous drainage, resulting in decreased shear stress and promoting a proinflammatory environment. Subsequently, venous wall infiltration and venule inflammation are thought to promote lymphocyte and erythrocyte migration across the blood–brain barrier. The resulting inflammation and iron deposition may be responsible for the inflammatory and degenerative lesions characteristic of MS.3 This theory gave rise to the so-called chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) syndrome, of which Doppler ultrasound-based criteria were defined by the authors.2 While Zamboni et al.4 reported on a perfect diagnosis accuracy of these criteria (classifying MS patients with a 100% sensitivity and specificity), further studies, using the same criteria, found partial, doubtful, or even no association between MS and venous drainage abnormalities.5, 6, 7

Phase-contrast MRI (PC-MRI) provides a rapid, non-invasive, and operator-independent assessment of venous drainage pathways, at both intracranial and cervical levels. The technique has previously enabled a quantitative characterization of venous flows in healthy young adults.8

In addition, comprehensive complementary study of dynamic interactions between the intracranial compartments is allowed. According to the Monro–Kellie doctrine, intracranial pressure homeostasis within the unexpandable cranial box is determined by the continuous adaptative volume variations in the three fluid-containing sectors: arterial, venous, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). At the beginning of each systole, instantaneous increase of the arterial total inflow should be rapidly compensated by sequential outflows of subarachnoid CSF, venous blood, and ventricular CSF. During the diastole, the same serial events are reversed. The sequence of these events has been previously described.9

The purpose of this study was to simultaneously quantify the venous, arterial, and CSF flows in MS patients, in comparison to age and gender-matched healthy adults. Our working hypothesis was that if MS was related to any venous flow modification, this dysfunction should be measurable by PC-MRI, and it should result in a modification of intracranial flows, particularly CSF.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Nineteen patients with MS were included. Age ranged from 21 to 52 years (median: 33 years; standard deviation (s.d.): 9). Eleven out of the 19 (58%) patients were female. Mean disease duration from clinical onset was 53 months (range: 1 to 165). Two sub-groups of patients were considered. The first sub-group consisted of seven patients (median age=28 years, s.d.: 11, female ratio: 71%) presenting within less than 4 months after the first clinical event suggestive of MS (clinically isolated syndrome or CIS), according to initial MRI features, presence of oligoclonal bands in CSF, and/or evoked potential abnormalities. The second sub-group included 12 patients (median age=31 years, s.d.: 7, female ratio: 50%) with a diagnosis of MS according to the revised McDonald criteria, presenting with a relapsing remitting (RR) course. The mean disease duration since clinical diagnosis was 85 months (range: 17 to 165). Exclusion criteria were: (i) clinical relapse or use of corticosteroids within the last 30 days; (ii) presence of any associated non-MS neurologic disorder; and (iii) contraindication to MR examination. MS patients were issued from a more comprehensive clinical study encompassing morphologic and volumetric acquisitions. The control group consisted of 21 age and gender-matched healthy controls (HC) without relevant medical history, recruited between good-willing hospital employees and spouses. Median age was 33 years (s.d.: 4), and 10 (48%) were female. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Commission d'Ethique Biomédicale Hospitalo-Facultaire de l′UCL), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Acquisition

All MRI examinations were performed on the same 3T system (Achieva 3T, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands), using a 32-channel head coil. Subjects were supine.

In all subjects, flow images were acquired using 2D Fast cine PC-MRI pulse sequence with retrospective peripheral gating, and 32 frames covering the entire CC were analyzed. Phase-contrast parameters were as follows: echo time TE=12–17 milliseconds; repetition time TR=30 milliseconds; flip angle: 15° field-of-view FOV=140 × 140 mm2; matrix 256 × 128; slice thickness 5 mm. SENSE reduction factor for parallel imagingoption was set at 1.8 for extracranial and intracranial blood flows, 1.6 for the cervical subarachnoid spaces, and 0 for the aqueduct. The parallel imaging allowed significant acquisition time reduction without interfering with measurements because of the limitation of the SENSE factor lower to 2 and the use of a 32-channel receiving coil. Velocity encoding sensitization was set at 80 cm/second for the vessels, 10 cm/second for the aqueduct, and 5 cm/second for the cervical subarachnoid space. Sagittal T1-weighted scout view images were used as localizer to prescribe slice locations for flow quantification, as illustrated in Figure 1. The acquisition planes were set in the most perpendicular location to the presumed direction of the flow. The acquisition time for each flow series was ∼90 to 150 seconds, with slight variations depending on the participant's heart rate, resulting in a total examination time of less than10 minutes.

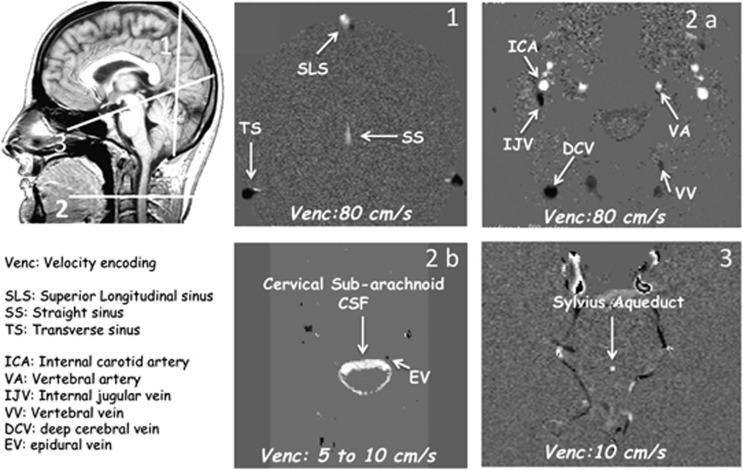

Figure 1.

Data acquisition. Sagittal scout view sequences were used as localizer to select the anatomic levels for flow quantification. The acquisition planes were selected perpendicular to the presumed direction of the flows. A coronal section (1), with a Venc (velocity encoding) fitted to vascular flows (at 80 cm/second), was used to measure venous flows in the superior longitudinal sinus (SLS), in the straight sinus (SS), and in the left and right lateral transverse sinuses (TS). Section through the C2–C3 level (2), using the same Venc (2a), was used to measure vascular flows in left and right internal carotid artery (ICA), vertebral artery (VA), internal jugular vein (IJV), vertebral vein (VV), deep cervical vein (DCV), and epidural vein (EV) (2b). By varying the Venc (5 to 10 cm/second), the same cervical section level (2b) was used to measure cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows in the cervical CSF subarachnoid spaces. Finally, a transverse section (3) perpendicular to the flow direction at the mid level of Sylvius aqueduct enabled measurement of the ventricular CSF flow. White pixels represent the flows entering in the section plane, black pixels represent flows directed out of the section plane, and gray pixels correspond to immobile tissues.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a free homemade image processing software (http://www.tidam.fr/) running an optimized CSF/blood flows segmentation algorithm, which automatically extracted the regions of interest at each level, and calculated flow curves over the 32 frames covering the whole CC. To correct for offsets in baseline velocity, a standard background was manually delineated in static tissues adjacent to each segmented regions of interest. Mean velocity curve of this noise area was calculated and subtracted to that of regions of interest, for each frame of the CC, thereby correcting for eddy currents effects. (More information about processing available in previously published papers8, 9).

Venous, arterial, and CSF flow curves were then generated at different time-points during the CC and analyzed.

For arterial flows, the so-called ‘mean total arterial blood flow' (tABF) was calculated in mL/minute at cervical level, and corresponded to the sum of flows within left and right internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and vertebral arteries (VAs).

The so-called cervical ‘primary venous blood flow' was calculated as the sum of the venous flows within the left and right internal jugular veins (IJVs), and the ‘secondary cervical venous blood flow' as the sum of the flows within the three main secondary venous pathways: epidural (EV), vertebral (VV), and deep cervical veins.

Both primary venous blood flow and secondary venous blood flow were as well expressed as percentage of the tABF. The difference between tABF and the sum of primary venous blood flow +secondary venous blood flow corresponded to undetected venous flow, and was therefore called ‘unmeasured venous flow'.

At the intracranial level, venous flows within the major intracranial sinuses were calculated: the superior longitudinal sinus, straight sinus, and the right and left transverse sinuses.

Cerebral venous blood flow (cVBF) was defined as the sum of mean venous flows within superior longitudinal sinus and straight sinus.

In addition, we compared flow values within left versus right major arterial (ICA, VA) and venous trunks (IJV), to detect a lateral dominance. A dominant flow was defined as a side difference of more than 50% in blood flow values.

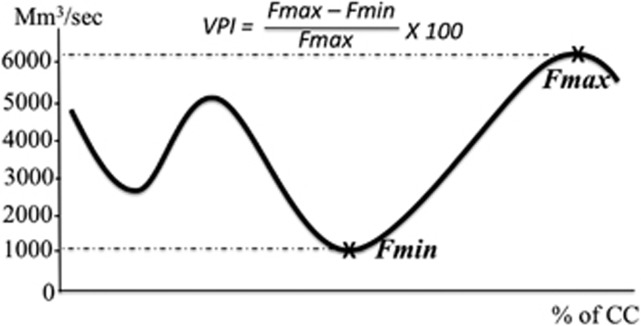

The venous pulsatility index (VPI), as previously defined, 8 was calculated at the cerebral level (venous flow oscillation within superior longitudinal sinus) and at the cervical level (flow oscillation within the dominant IJV). Minimum and maximum flow amplitudes (abbreviated as Fmin and Fmax, respectively) were extracted (Figure 2), and VPI was calculated as follows: VPI=100 × (Fmax−Fmin)/Fmax.

Figure 2.

Venous flow curve. The venous flow in an internal jugular vein is plotted during the cardiac cycle (CC), and expressed in millimeters per second. The maximum (Fmax) and the minimum (Fmin) amplitude of the venous flow are represented with stars, and enable calculation of venous pulsatility index (VPI).

At last, CSF flow curves at the aqueductal and cervical levels were integrated in both positive and negative CC phases, providing the CSF stroke volumes (SV), defining mean CSF volumes displaced in one direction or the other through the considered regions of interest at each level.10, 11

Statistical Analysis

Median values were calculated for all parameters in MS and HC's groups.

Non-parametric statistical tests were chosen.

Comparison between the two groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney test for vascular flows and CSF stroke volumes.

To investigate the impact of disease duration on dynamic flow oscillations, a one-way analysis of variance was also performed, together with post hoc analysis when needed, comparing results in HC and the two sub-groups of patients (CIS and RR).

A standard level for statistical significance (P-value) was set at 0.05.

Results

An excellent detection rate was obtained for veins in both groups.

In HC, venous flows were obtained only in 20 subjects and 19 out of 21 at the cervical and intracranial levels respectively, for technical reasons. For identical reasons, in the 19 MS patients, venous flow was obtained in all 19 MS patients at the cervical (IJV) level, while obtained in 18 patients out of 19 in the transverse sinus.

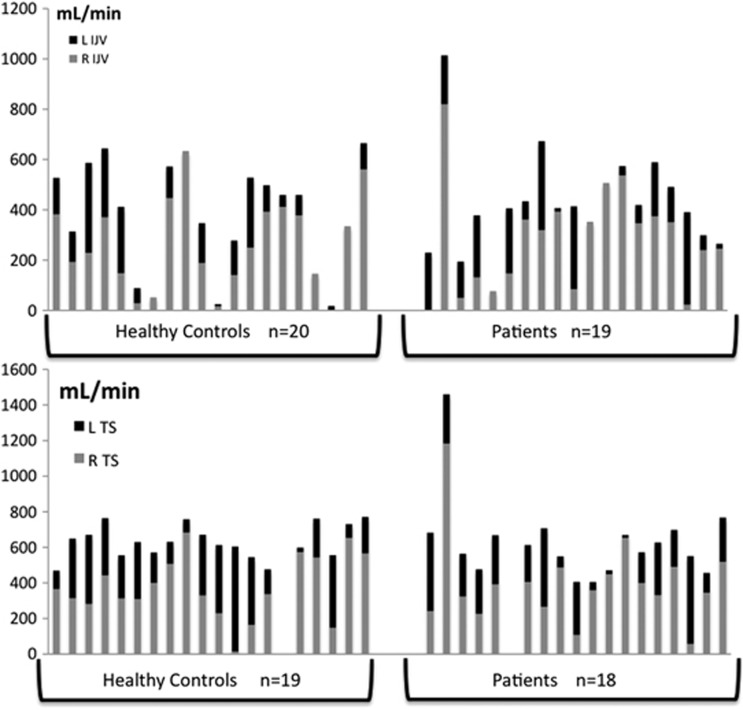

Heterogeneity of values together with elevated standard deviations reflected high dispersion of venous flows, mainly in the jugular veins. A significant right-sided dominance in the jugular veins and transverse sinuses was demonstrated, contrasting with results in the arterial vessels. The distribution of venous flows in the right and left jugular veins and the transverse sinuses is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Side repartition of venous flows. Venous flows are represented, in mL/minute, in healthy controls and subjects. They are represented at cervical level (internal jugular veins or IJV) in the upper part of the figure, and at cerebral level (transverse sinuses or TS) in the bottom part. Individual flows are represented as columns, with, for each subject, the right flow (R) represented with the gray part of the column, while left flow (L) represented in black. Right dominance is significantly expressed in venous pathways, with larger gray parts in the majority of columns, in both populations, at both IJV and TS levels.

On the arterial side, equal distribution between the right and left ICA was observed in 100% of the HC and 95% of the MS patients. In VA, flows showed right-sided dominance, left-sided dominance, and equal distribution in respectively 20%, 40%, and 40% of the HC, compared with 16%, 53%, and 31% of the MS patients (not significant).

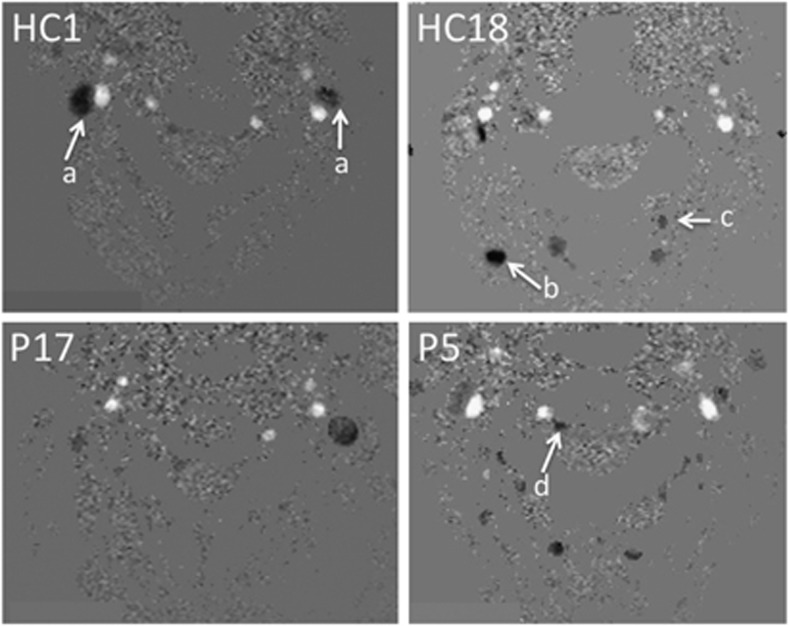

Secondary venous pathways had a key role in cerebral venous blood drainage, but with similar variability in HC and in MS patients: in some subjects, they may only represent a minor pathway when compared with jugular flow, while they may equal primary jugular cerebral venous flows in other subjects, or even constitute the prominent drainage pathway in others. The variability of this distribution in the two populations is shown on Figure 4. Additionally, examples of venous flow patterns in two patients and two controls are given on Figure 5.

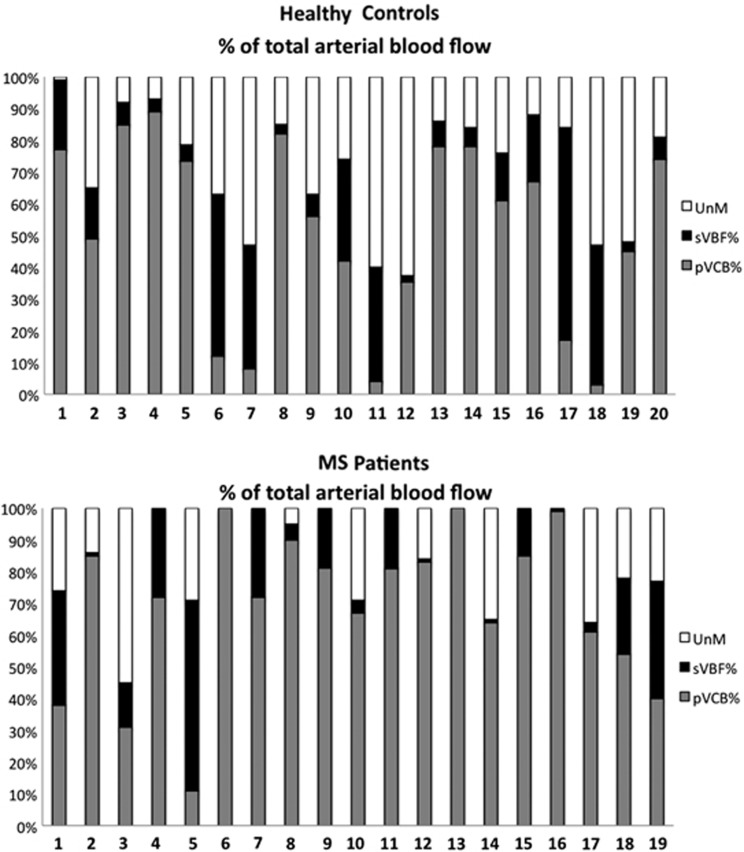

Figure 4.

Primary and secondary venous pathways. The upper figure represents venous cervical flows obtained in 20 healthy control (HC) out of 21, while the lower corresponds to the 19 multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. Each column represents venous flows detected at the cervical level, expressed as a percentage of total arterial blood flow (tABF). The gray part corresponds to the primary venous flow's (both left and right jugular veins) participation to the drainage of arterial cerebral flow. Black rectangle corresponds to the secondary venous flow's (epidural, vertebral, and deep cervical veins) participation to the drainage of arterial cerebral blood flow. The white rectangle represents the difference between the arterial blood flow and the sum of primary and secondary venous flows (tABF−(pVCB+sVBF)), called ‘unmeasured venous flow' (unM). This figure illustrates the heterogeneity of venous flow drainage patterns, in both populations: the participation of ‘primary' jugular veins to the total drainage of venous blood is heterogeneous, in HC as well as in MS patients. The participation of ‘secondary' pathways is greatly variable, sometimes largely exceeding jugular drainage (i.e., HC17, P5).

Figure 5.

Illustration of physiologic variation of venous drainage pathways. Axial views at the cervical level show the venous and arterial vessels in four subjects: two healthy controls (HC) and two multiple sclerosis (MS) patients (P). In the first HC (HC1), we observe a clearly predominant jugular drainage (arrow a), right dominant, without detected accessory venous drainage. An exclusive jugular, strictly unilateral (unique left internal jugular vein (IJV)) is shown in a MS patient (P17). On the contrary, a preponderant role of accessory venous drainage pathways can be observed, in HC as well as in MS patients: in HC2, only a slight flow is detected in the right IJV, while the left one is undetected. The venous drainage is mainly shunted to the deep cervical (arrow b) and the vertebral (arrow c) veins (HC18). Accessory venous drainage is also obvious in the epidural veins (arrow d in P5).

Notably, none of the venous flow in any venous vessel, in any participant, crossed the 0 line, which signified that only flows in the craniocaudal direction were observed throughout the CC, and that no reflux was recorded in the venous flows (Figure 2).

Table 1 compares calculated median flow values between HC and MS populations.

Table 1. Flows comparison between MS and HC populations.

| HC | MS (CIS+RR) | CIS | RR MS | p1 | p2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb | 21 | 19 | 7 | 12 | ||

| Age (median) | 33±4 | 33±9 | 28±11 | 31±8 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Heart Rate (/min) | 66±10 | 69±13 | 77±16 | 69±10 | 0.2 | 0.06 |

| Female ratio (%) | 48 | 58 | 71 | 50 | ||

| Cerebral venous flows | ||||||

| SLS | 281±59 | 251±78 | 279±63 | 250±88 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| SS | 127±31 | 115±42 | 127±24 | 104±48 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| R TS | 337±178 | 376±243 | 406±134 | 400±315 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| L TS | 242±147 | 245±142 | 240±128 | 220±152 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| R>L | 9 | 10 | ||||

| L>R | 4 | 4 | ||||

| E | 6 | 4 | ||||

| cVBF | 396±70 | 378±111 | 407±66 | 357±132 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| VPI a | 26±5 | 31±9 | 28±13 | 33±2 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Cervical venous flows | ||||||

| R IJV | 240±182 | 282±207 | 250±205 | 301±231 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| L IJV | 104±107 | 145±127 | 120±87 | 159±150 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| R>L | 12 | 12 | ||||

| L>R | 4 | 2 | ||||

| E | 4 | 5 | ||||

| pVBF | 430±209 | 407±202 | 370±202 | 461±220 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Ratio/arterial (%) | 58±29 | 69±26 | 63±36 | 73±15 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

| sVBF | 63±152 | 85±111 | 155±136 | 77±91 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Ratio/arterial (%) | 8±19 | 14±17 | 24±20 | 14±16 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| VPI a | 58±17 | 61±18 | 56±20 | 64±16 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Unmeasured (%) | 24±18 | 14±19 | 13±24 | 13±15 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Cervical arterial flows | ||||||

| R ICA | 271±35 | 226±90 | 233±50 | 237±110 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| L ICA | 265±37 | 218±65 | 211±26 | 243±74 | 0.05 | 0.2 |

| R VA | 80±34 | 71±37 | 84±44 | 64±35 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| L VA | 109±36 | 95±42 | 81±57 | 86±30 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| tABF | 699±81 | 614±163 | 609±68 | 630±190 | 0.02 | 0.5 |

| Cervical CSF SV | 727±244 | 549±145 | 605±155 | 525±131 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| Aqueductal CSF SV | 41±17 | 44±25 | 39±24 | 53±26 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Abbreviations: CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; cVBF, cervical venous blood flow; E, equal distribution; HC, healthy controls; ICA, internal carotid artery; IJV, internal jugular vein; L, left; MS, multiple sclerosis; pVBF, primary venous blood flow; R, right; RR, relapsing remitting; SLS, superior longitudinal sinus; SS, straight sinus; sVBF, secondary venous blood flow; TS, transverse sinus; VA, vertebral artery; tABF, total arterial blood flow.

Median values are represented for each parameter in each population. p1 refers to P-value in Mann–Whitney analysis comparing MS and HC groups, while p2 refers to P-value in multivariate analysis comparing HC to CIS and RR groups of patients.

Cervical and aqueductal CSF stroke volumes are expressed in μL per cardiac cycle.

Refers to venous pulsatility index, expressed as an indicator, without unit.

Venous flows were not significantly different between groups. Similar oscillating properties within venous trunks were found in the two populations, with the cervical jugular veins exhibiting greater oscillating properties (assessed by higher VPI) than the intracranial dural sinuses.

One-way analysis of variance analysis, comparing HC to MS patients split into two sub-groups (CIS and RR) failed to reveal any significant difference in venous flows between groups.

In turn, tABF values were significantly decreased (by approximately 14%, P=0.02) in MS patients when compared with HC, mainly within left ICA. Although multivariate analysis failed to detect a significant impact of disease stage (CIS versus RR) on arterial flow dynamics, the tABF was mostly decreased in CIS patients when compared with HC, with the reserve of a very small-sized CIS subgroup (n=7).

Significant reduction of CSF oscillations at the cervical level was observed in MS patients (24% when compared with HC, P=0.01). Although multivariate analysis did not reach significance level, the most relevant decrease was recorded in RR patients when compared with HC.

Discussion

The venous hypothesis in MS was revived by the findings of Zamboni et al.2 who highlighted venous flow abnormalities at transcranial color-coded Duplex sonography in 100% of MS patients, with even specific patterns for each phenotype of the disease. Their results were confirmed, although in lower proportion and small populations, in some publications.12, 13 However, further studies, using the same technique, failed to reproduce these results. Venous stenoses were not detected, and only one or the other criterion of the venous hemodynamic abnormalities was found, with similarly low frequency in both MS patients and HC.5, 14 Moreover, Mayer et al.6 failed to highlight at least one of the proposed criteria in MS patients. This study, although limited on a small sample size (n=20), was carefully designed, with a masking procedure to avoid bias. Furthermore, although suggested to have a causative role in MS, CCSVI abnormalities were not confirmed in early stages of MS, such as in patients with CIS7 or as MS with early pediatric onset.15 Transcranial color-coded sonography is an imaging method with many advantages (rapid, cheap, realization on patient's bedside), but suffers significantly limiting factors such as operator's skills and experience, head position, respiration, heart rate, external compression, hydration status, as well as factors related to the absence of blinding, and to some technical factors.16

In turn, PC-MRI, especially using semi-automatic segmentation algorithms,9 offers operator-independent, rapid, non-invasive; and reproducible quantitative assessment of extracranial and intracranial flows. Moreover, its relevance in venous flow quantification has been demonstrated in healthy subjects in a previous study,8 and results were validated because they were similar to those of the invasive catheter venography, stated as the gold-standard reference technique. Finally, it offers the unique opportunity of evaluating the venous system as a component of the global multi-compartmental system regulating intracranial pressure, with regards to arterial and CSF flows.

Venous Flows

Venous flows were tightly comparable in MS patients and in age-matched controls, at both extracranial and intracranial levels, independently of the disease duration, as demonstrated by the absence of significant differences between MS sub-groups. The absence of relevant abnormal venous drainage has been recently reported in PC-MRI studies of cervical (IJV)17, 18, 19 or intracranial (internal cerebral veins and straight sinus) flows,20 matching the absence of concomitant abnormalities at MR venograms.18, 19, 20 Other studies, using time-of-flight venography of the jugular veins in a larger population of MS patients, failed to reveal any difference in morphologic flow features when compared with healthy subjects.21

The present work is the first study combining venous flow quantification at both the cervical and intracranial levels.

Whether MS had been related to insufficient venous drainage at the cervical or thoracic level, then abnormal dynamics of venous oscillations should have been recorded, primarily within the cervical IJV, and secondarily at the intracranial level, where venous insufficiency would have resulted in abnormalities in CSF dynamics and composition.

By comparing oscillation patterns of veins and sinuses, we found that these two compartments had strongly different properties, as previously reported:8 the jugular veins have higher VPI, and thus higher elasticity; in turn, the sinuses have lower compliance, as shown by less pulsatile flow during the CC.

Notably, those venous pulsatile properties were unchanged in MS patients, thereby maintaining the compliance of the venous system, at cervical and intracranial levels, which has a key role in the preservation of the intracranial pressure homeostasis.

Venous flows analysis revealed major heterogeneity, in comparable range in both MS and HC populations.

Right-sided dominance was prevalent in IJV and transverse sinus in the two populations, contrasting with homogeneous repartition within the arteries (mainly ICA), as it has been previously described in HC using PC-MRI8 or venographic techniques.22, 23

Contribution of venous accessory drainage pathways has been neglected in the CCSVI definition, except for the vertebral vein. Although initially described as accessory, the secondary venous pathways, namely epidural vein, vertebral vein, and deep cervical vein, are now recognized to represent a significant fraction of the venous cranial drainage, depending on posture (sitting or standing position, in which the jugular veins collapse) or on intrathoracic pressure.24, 25, 26 Moreover, a previous PC-MRI study performed on HC has demonstrated that the role of secondary venous pathways may be physiologically variable, independently of posture-related factors.8

These heterogeneous venous flow patterns observed in MS patients as well as in HC renders difficult to assess ‘venous obstructions,' as distinguishing between physiologic side dominance, secondary venous drainage preponderance, or venous obstruction may be challenging in subjects with flow asymmetry.

In a recent study using PC-MRI venous quantification, Ertl-Wagner et al.17 found that MS patients had increased participation of venous accessory drainage when compared to HC, although this feature was unspecific for MS, because it was observed in non-MS participants with migraine. Nevertheless, in this study, the authors found a wide variability in venous flow distribution, comparable to our results, which makes difficult to reach any definite conclusion about a prominent pattern in these populations.

Arterial Flows

Recent publications have stressed the role of venous insufficiency as a main triggering factor in various cerebral diseases, such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension or normal-pressure hydrocephalus.27 However, arterial flows remain the ‘driving force' initiating the mechanical coupling between the intracerebral compartments,28 and maintaining intracranial pressure equilibrium throughout the CC. Arterial input should therefore be analyzed concomitantly to venous flows.

Our results highlighted the main vascular difference between MS and HC was a decrease in arterial input in patients, mainly in the carotid circulation. This reduction was observed even at early stages of the disease (patients with CIS). Although not significantly, arterial total CBF tended to be lower in patients with MS in a previous study using PC-MRI.18

Using dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MRI, researchers have initially detected ‘patchy' pattern of focal CBF modifications, presumptively corresponding to a patchwork of alternating areas of increased regional cerebral blood volume due to vasodilatation within perivascular acute inflammation and areas of decreased regional cerebral blood volume in chronic lesions with axonal damage.29

Other possible underlying mechanisms were later suggested. Recent studies using MRI or metabolic PET studies30, 31 have highlighted a reduction of arterial inflow within the damaged white matter, particularly the periventricular normal-appearing white matter,32, 33 extending to the cerebral cortex and deep gray matter. Cerebral hypoperfusion in MS patients was mainly assumed to be secondary to reduced metabolic demand due to axonal degeneration. Further extension to the cerebral cortex and deep gray matter was assumed to result from a secondary disconnection between cerebral cortex and subcortical areas, because of underlying white matter damage.

Contradictorily, recent works demonstrated that the widespread cerebral hypoperfusion occurs since the early stages of MS, and thus precedes brain atrophy.34, 35 Underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are complex and remain partially resolved. They suggest the central role of astrocyte energy metabolism reduction, responsible for enhanced nitric oxide levels (oxidative mechanisms contributing to degeneration) and decreased formation of lactate and glutamate, which are energy sources for axons (axonal mitochondrial dysfunction). In addition, the astrocytes produce and release high levels of endothelin-1 that may reach the intracerebral arterioles and induce long-lasting vasoconstriction.36

CSF Dynamics

Cerebrospinal fluid stroke volume was significantly decreased at the cervical level in MS patients but was preserved at the aqueductal level. Cerebrospinal fluid stroke volumes reflect the ‘mobile compliance' of each compartment, and contribute to rapid regulation of intracranial pressure throughout the CC.

To our opinion, these results are mainly related to arterial perfusion decrease. According to the Monro–Kellie doctrine, the systolic phase of the CC is characterized by a sudden dramatic increase in arterial input, which must be dampened by an equal intracranial volume withdrawal, to maintain the intracranial pressure homeostasis. The first removable volume is the cervical CSF; its flush through the subarachnoid spaces enables brain expansion. Consequently, cerebral subarachnoid spaces pressure drops, resulting in venous cerebral and cervical flush, and finally, ventricular CSF flush occurs through the aqueduct and at the third ventricle and Monro levels.9

If the arterial inflow is decreased, less energy is transferred from the arterial tree to the CSF, of which oscillations lessen. As cervical CSF oscillating volume is more than 12-fold higher than aqueductal one, the subarachnoid cervical CSF is the main compartment reflecting the reduction in arterial pulsatility.

Previous studies using different quantitative parameters of aqueductal CSF dynamics, solely37, 38 or in combination with the analysis of arterial and venous jugular flows18 have found heterogeneous and contradictory results.

The Swedish group18 found results in concordance with ours; they used the same definition and calculation method for CSF stroke volume (i.e., integration of the area under the CSF curve during one CC) and failed to reveal any significant difference between MS and HC.

Gorucu et al.38 found increased CSF volume oscillations in both craniocaudal and caudocranial directions, as well as increased net flow (difference between these two volumes), only when calculated in mL/minute, but, unexpectedly, not when expressed in μL/CC.

Magnano et al.37 using comparable definitions, concluded that MS patients had higher net positive CSF flows in caudocranial direction (reflecting increased CSF pulsatility in the aqueduct) contrasting with reduced CSF net flow (reflecting decreased CSF drainage). They hypothesized that the increased pulsatile flow could lead to increased perfusion and permeability of the ventricles, thereby resulting in higher accumulation of periventricular and deep white matter lesions.

The measurement technique in those two studies was different from ours. Their selected velocity encoding (20 cm/second) was exceedingly above the range of measured CSF velocities at the aqueductal level, which can decrease the signal–to-noise ratio, thereby resulting in lower precision of measurements.

Moreover, low values of mean calculated net flow, and high values of standard deviations probably exceeded the limits of the technique's accuracy. Conclusions should therefore be drawn cautiously: it seems inappropriate to extrapolate conclusions about complex, circadian-related CSF secretion, from a single value obtained at only one time point through a short calculation during a few CCs, with high susceptibility to respiratory motion.

In addition, none of the two latter studies have analyzed CSF oscillations with regards to the arterial dynamics, which represent the ‘driving force' initiating the complex cerebral hydraulic regulatory mechanisms. Nor did they measure the venous flows. However, they concluded that the observed CSF flow abnormalities could be related to disturbed venous drainage.

Limits

As several technical and measurement difficulties have to be taken into account when studying flows, we considered different conditions to enhance reliability and reduce limits in this evaluation.

Vascular flow measurements with PC-MRI have been performed in different cardiac and neurologic applications, and seem thus far reliable, provided that velocity encoding is appropriately chosen.39

The main challenge was measuring aqueductal CSF flow, because of the very small caliber of the aqueduct. However, previous studies have demonstrated a good reliability of PC-MRI CSF quantification,40 mainly when semi-automated algorithm is used, because it minimizes velocity dispersion when compared with manual contouring.9 Similar reliability was obtained with these segmentation softwares for assessing cervical CSF flows in this anatomically challenging area.9

Conclusion

Since its initial description in 2009, the hypothesis of CCSVI has raised a passionate debate among the scientific community, which extended to the media and patients, provoking a rise in percutaneous endovascular dilatation procedures; the importance of this controversy and of its potential impact on the therapeutic strategies render mandatory to demonstrate whether CCSVI truly exists in MS patients.

Our study using PC-MRI reports on an exhaustive quantification of the arterial, venous, and CSF intracranial flows. We failed to demonstrate significant venous flow abnormalities in MS patients, e.g., no venous reflux, which is supposed to be frequent in CCSVI. We documented complex and heterogeneous venous drainage pathways, which did not significantly differ between MS patients and HC. An arterial cerebral hypoperfusion was highlighted in MS patients, even those with CIS, mainly in the carotid arteries, in accordance with previous dynamic and metabolic studies, which resulted in a decrease of CSF dynamic oscillations, thereby preserving intracranial homeostasis.

To our opinion, there is so far no robust data supporting the occurrence of CCSVI in MS. In contrast, the reduction of arterial flow in the carotid circulation in MS patients warrants further studies.

Dr Elsankari has received honoraria for lectures from BayerSchering and BiogenIdec, and travel expenses for attending meetings from BayerSchering, BiogenIdec, Merck-Serono, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Dr van Pesch has received honoraria for lectures from BayerSchering, Novartis and BiogenIdec, and travel expenses for attending meetings from BayerSchering, BiogenIdec, Merck-Serono, Novartis and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Professor Sindic has received honoraria for consultancy, board membership, and lectures from BayerSchering, BiogenIdec, GSK Biological Vaccines, Merck-Serono, Novartis and Sanofi Aventis, and research grants from BayerSchering, Merck-Serono and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study was funded by La Fondation Roi Baudoin and La Ligue Nationale Belge de la Sclérose en Plaques (Convention N: 2010-R12060-002).

References

- Zamboni P, Menegatti E, Bartolomei I, Galeotti R, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, et al. Intracranial venous haemodynamics in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:252–258. doi: 10.2174/156720207782446298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, Dall'Ara S, et al. Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple scleorsis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:392–399. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.157164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dake MD. Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis: history and background. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;15:94–100. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni P, Menegatti E, Galeotti R, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, Dall'Ara S, et al. The value of cerebral Doppler venous haemodynamics in the assessment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;282:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doepp F, Paul F, Valdueza JM, Schmierer K, Schreiber SJ. No cerebrocervical venous congestion in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:173–183. doi: 10.1002/ana.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer CA, Pfeilschifter W, Lorenz MW, Nedelmann M, Bechmann I, Steinmetz H, et al. The perfect crime? CCSVI not leaving a trace in MS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:436–440. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.231613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baracchini C, Perinin P, calabrese M, Causin F, Rinaldi F, Gallo P. No evidence of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency at multiple sclerosis onset. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:90–99. doi: 10.1002/ana.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoquart-Elsankari S, Lehmann P, Villette A, Czosnyka M, Meyer M.E, Deramond H, et al. A phase-contrast study of physiologic cerebral venous flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baledent O, Henry-Feugeas MC, Idy-Peretti I. Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and relation with blood flow: a magnetic resonance study with semi-automated cerebrospinal fluid segmentation. Invest Radiol. 2001;36:368–377. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitz WR, Bradley WG, Jr, Watanabe AS, Lee RR, Burgoyne B, O'Sullivan RM, et al. Flow dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid: assessment with phase-contrast velocity MR imaging performed with retrospective cardiac gating. Radiology. 1992;183:395–405. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.2.1561340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzmann DR, Pelc NJ.Cerebrospinal fluid flow measured by phase-contrast cine MR AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993141301–1307., (discussion 1309-10). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omari MH, Rousan LA. Internal jugular vein morphology and hemodynamics in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int Angiol. 2010;29:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simka M, Kostecki J, Zaniewski M, Majewski E, Hartel M. Extracranial Doppler sonographic criteria of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in the patients with multiple sclerosis. Int Angiol. 2010;29:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Gupta P, Greenberg BM, Frohman EM, Awad AM, Bagert B, et al. No cerebral or cervical venous insufficiency in US veterans with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;68:1521–1525. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato MP, Saia V, Hakiki B, Giannini M, Pasto L, Zecchino S, et al. No association between chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1791–1796. doi: 10.1177/1352458512445943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdueza JM, Doepp F, Schreiber SJ, van Oosten BW, Schmierer K, Paul F, et al. What went wrong? The flawed concept of cerebrospinal venous insufficiency. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:657–668. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl-Wagner B, Koerte I, Kumpfel T, Blaschek A, Laubender RP, Schick M, et al. Non-specific alterations of craniocervical venous drainage in multiple sclerosis revealed by cardiac-gated phase-contrast MRI. Mult Scler. 2011;18:1000–1007. doi: 10.1177/1352458511432742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom P, Wahlin A, Ambarki K, Birgander R, Eklund A, Malm J. Venous and cerebrospinal fluid flow in multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:255–259. doi: 10.1002/ana.22132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinkenberg M, Akeson P, Sillesen H, Lovgaard S, Sellebjerg F, Paulson OB, et al. Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and venous stenoses in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;126:421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2012.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattjes MP, van Oosten BW, de Graaf WL, Seewann A, Bot JC, van den Berg R, et al. No association of abnormal cranial venous drainage with multiple sclerosis: a magnetic resonance venography and flow-quantification study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:429–435. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.223479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinov R, Lopez-Soriano A, Weinstock-Guttman B, Schirda CV, Magnano CR, Dolic K, et al. Use of MR venography for characterization of the extracranial venous system in patients with multiple sclerosis and healthy control subjects. Radiology. 2011;258:562–570. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgun B, Ilglt ET, Cizmeli MO, Atasever A. Evaluation by angiography of the lateral dominance of the drainage of the dural venous sinuses. Surg Radiol Anat. 1993;15:125–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01628311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanzen RH, Bird CR, Keller PJ, McCully FJ, Theobald MR, Heiserman JE. Cerebral MR venography: normal anatomy and potential diagnostic pitfalls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:74–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alperin N, Hushek SG, Lee SH, Sivaramakrishnan A, Lichtor T. MRI study of cerebral blood flow and CSF flow dynamics in an upright posture: the effect of posture on the intracranial compliance and pressure. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:177–181. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilenge D, Perey B. An angiographic study of the meningorachidian venous system. Radiology. 1973;108:333–337. doi: 10.1148/108.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirovic S, Walsh C, Fraser WD, Gulino A. The effect of posture and positive pressure breathing on the hemodynamics of the internal jugular vein. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman GA, Smith RL, Siddique SH. Idiopathic hydrocephalus in children and idiopathic intracranial hypertension in adults: two manifestations of the same pathophysiological process. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:439–444. doi: 10.3171/PED-07/12/439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitz D, Wirestam R, Franck A, Nordell B, Thomsen C, Stahlberg F. Pulsatile brain movement and associated hydrodynamics studied by magnetic resonance imaging. The Monro-Kellie doctrine revisited. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:370–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00596493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselhorst R, Kappos L, Bilecen D, Scheffler K, Mori D, Radu Ew, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast MR imaging of plaque development in multiple sclerosis: Application of an extended blood-brain barriere leakage correction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:495–505. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(200005)11:5<495::aid-jmri5>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Tanaka M, Kondo S, Okamoto K, Hirai S. Clinical significance of reduced cerebral metabolism in multiple sclerosis: a combined PET and MRI study. Ann Nucl Med. 1998;12:89–94. doi: 10.1007/BF03164835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhya S, Johnson G, Herbert J, Jaggi H, Babb JS, Grossman RI, et al. Pattern of hemodynamic impairment in multiple sclerosis: dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MR imaging at 3.0 T. Neuroimage. 2006;33:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M, Saindane AM, Ge Y, Babb JS, Johnson G, Mannon LJ, et al. Microvascular abnormality in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: perfusion MR imaging findings in normal-appearing white matter. Radiology. 2004;231:645–652. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313030996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaci FG, Marziali S, Meschini A, Fornari M, Rossi S, Melis M, et al. Brain hemodynamic changes associated with chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency are not specific to Multiple Sclerosis and do not increase its severity. Radiology. 2012;265:233–239. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelman AP, van de Graaf Y, Vincken KL, Tiehuis AM, Witkamp TD, Mali WP, et al. Total cerebral blood flow, white matter lesions and brain atrophy: the SMART-MR study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:633–639. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AW, Johnson G, Babb JS, Herbert J, Grossman RI, Inglese M. White matter hemodynamic abnormalities precede sub-cortical gray matter changes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;282:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeseleer M, Cambron M, Vanopdenbosch L, De Keyser J. Vascular aspects of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnano C, Schirda C, Weinstock-Guttman B, Wack DS, Lindzen E, Hojnacki D, et al. Cine cerebrospinal fluid imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:825–834. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorucu Y, Albayram S, Balci B, Hasiloglu ZI, Yenigul K, Yargic F, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics in patients with multiple sclerosis: a phase contrast magnetic resonance study. Funct Neurol. 2011;26:215–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baledent O, Fin L, Khuoy L, Ambarki K, Gauvin AC, Gondry-Jouet C, et al. Brain hydrodynamics study by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial color doppler. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:995–1004. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetmer PH, Huston J, Friedman JA, Dixon GR, Petersen RC, Jack CR, et al. Measurement of cerebrospinal fluid flow at the cerebral aqueduct by use of phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging: technique validation and utility in diagnosing idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:534–543. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]