Abstract

Th9 cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells, shown to be important in allergy, autoimmunity and anti-tumor responses. However, their role in human infectious diseases has not been explored in detail. We identified a population of IL-9 and IL-10 co-expressing cells (lacking IL-4 expression) in normal individuals that respond to antigenic and mitogenic stimulation but are distinct from IL-9+ Th2 cells. We also demonstrate that these Th9 cells exhibit antigen –specific expansion in a chronic helminth infection (lymphatic filariasis). Comparison of Th9 responses reveals that individuals with pathology associated with filarial infection exhibit significantly expanded frequencies of filarial antigen induced Th9 cells but not of IL9+Th2 cells in comparison to filarial-infected individuals without associated disease. Moreover, the per cell production of IL-9 is significantly higher in Th9 cells compared to IL9+Th2 cells, indicating that the Th9 cells are the predominant CD4+ T cell subset producing IL-9 in the context of human infection. This expansion was reflected in elevated antigen stimulated IL-9 cytokine levels in whole blood culture supernatants. Finally, the frequencies of Th9 cells correlated positively with the severity of lymphedema (and presumed inflammation) in filarial diseased individuals. This expansion of Th9 cells was dependent on IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1 in vitro. We have therefore a identified an important human CD4+ T cell subpopulation co – expressing IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4 that is whose expansion is associated with disease in chronic lymphatic filariasis and could potentially play an important role in the pathogenesis of other inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Traditionally associated with the Th2 response, IL-9 is a member of the common γ chain cytokine family and exerts broad effects on many cell types including mast cells, eosinophils, T cells and epithelial cells (1, 2). However, it has become apparent from studies in mice that many different CD4+ T cell subsets have the capacity to secrete IL-9. A subset of IL-9 producing CD4+ T cells (Th9 cells) distinct from Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells has been identified (3, 4). These Th9 cells are characterized by the coincident production of IL-9 and IL-10 and develop from naïve CD4+ T cells under the combined influence of IL-4 and TGFβ (3, 4). It has also been shown that IL-9 secretion of murine Th2 cells is also dependent on TGFβ and that TGFβ can redirect committed Th2 cells towards the Th9 phenotype (4). IL-1 family members may also contribute to IL-9 production (5). Moreover, regulatory T cells expressing IL-9 have been described to play a role in the induction of peripheral tolerance (6). Finally, murine Th17 cells have also been shown to secrete significant amounts of IL-9 (7). Very few studies have examined the role of Th9 cells in humans. Th9 cells in humans were initially described as IL-9 cells co-expressing IL-17 (8), however, IL-9 producing CD4+ T cells distinct from Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells have also been recently described (9, 10). Th9 cells, in humans, are thought to play an important role in allergy (11), atopy (12), asthma (11), auto-immunity (13) and anti-tumor immunity (14). Although, IL-9 has been implicated in resistance to intestinal helminth infection (15, 16), the role of IL-9 in human parasitic infections is not known. Moreover, data on the role of Th9 cells in any infectious disease are scant.

Lymphatic filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by nematode worms that can manifest itself in a variety of clinical and subclinical conditions (17). While the majority of the 120 million infected individuals are clinically asymptomatic, a significant minority of individuals (~40 million) are known to develop lymphatic pathology following infection. The most common pathological manifestations of lymphatic filariasis are adenolymphangitis, hydrocele and lymphedema (elephantiasis in its most severe form) (17). The pathogenesis of lymphatic filarial disease is thought to be associated with the expansion of antigen-responsive Th1 and Th7 cells (18, 19).

While, Th9 cells have been shown to act as mediators of inflammation in experimental disease models, such as colitis, peripheral neuritis and experimental autoimmune encephalitis (3, 7, 20), IL-9 has also been shown to participate in peripheral tolerance by increasing the survival and activity of regulatory T cells (21). Therefore, it is still unclear whether IL-9 mediates pro –or anti – inflammatory activity. Since filarial infection exhibits differences in clinical manifestations with both an inflammatory component (filarial disease) and a non- inflammatory component (asymptomatic infection), we postulated that this infection would provide an ideal milieu to examine the role of Th9 cells in inflammation and infection.

We first identified a population of IL-9 and IL-10 co – expressing CD4+ T cells (Th9 cells) that can be distinguished from IL-9+Th2 cells and demonstrate their expansion in response to both cognate antigen and mitogen stimulation. We next demonstrated that this Th9 population was expanded in filarial disease (lymphedema) and their frequencies were directly related to the severity of disease. Moreover, this expansion appears to be critically dependent IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We first studied a group of 15 normal individuals (NL). We later expanded the study to include 47 individuals with filarial lymphedema (hereafter CP) and 39 clinically asymptomatic, filarial infected (hereafter INF) individuals in an area endemic for LF in Tamil Nadu, South India (Table 1). All normal individuals were circulating filarial antigen negative and without any signs or symptoms of infection or disease. All CP individuals were circulating filarial antigen negative by both the ICT filarial antigen test (Binax, Portland, ME) and the TropBio Og4C3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Trop Bio Pty. Ltd, Townsville, Queensland, Australia), indicating a lack of current active infection.. The diagnosis of prior filarial infection was made by history and clinical examination as well as positive Brugia malayi antigen (BmA) -specific IgG4. BmA-specific IgG4 and IgG ELISA were performed exactly as described previously (22). The illness of each CP individual was classified according the standard 4 grades that been established by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]: grade 1, pitting edema that is reversible by elevation of the affected limb; grade 2, pitting/nonpitting edema that is not reversible by elevation of affected limb; grade 3, nonpitting edema that is not reversible by elevation of the affected limb and that is accompanied by thickening of the skin; grade 4, nonpitting edema of the limb that is accompanied by fibrotic and verrucous skin changes (elephantiasis). All INF individuals tested positive for active infection by both the ICT filarial antigen test and the TropBio Og4C3 ELISA and had not received any anti-filarial treatment prior to this study. There were no differences between the groups in terms of demographics or socioeconomic status. All individuals were examined as part of clinical protocols approved by Institutional Review Boards of both the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis (NCT00375583 and NCT00001230), and informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

| CPa (n=47) | INF (n=39) | NL (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 44 (29–65) | 39 (23–65) | 36 (24–65) |

| Gender male/female | 33/14 | 29/10 | 9/6 |

|

| |||

| Lymphedema/Elephantiasis | Yes | None | None |

|

| |||

| ICT card test | Negative | Positive | Negative |

|

| |||

| W. bancrofti circulating antigen levels (U/ml) [GM (Range)] | < 32b | 1409 (138–22377) | <32 |

CP refers to individuals with filarial pathology, INF refers to individuals with asymptomatic, filarial infection and NL refers to endemic normal individuals.

Below the limits of detection.

Parasite and control antigen

Saline extracts of B. malayi adult worms (BmA) and microfilariae (Mf) were used for parasite antigens and mycobacterial PPD (Serum Statens Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used as the control antigen. Final concentrations were 10 μg/ml for BmA, Mf and PPD. Endotoxin levels in the BmA was < 0.1 EU/ml using the QCL-1000 Chromogenic LAL test kit (BioWhittaker). Phorbol myristoyl acetate (PMA) and ionomycin at concentrations of 12.5 ng/ml and 125 ng/ml (respectively), were used as the positive control stimuli.

In vitro culture

Whole blood cell cultures were performed to determine the frequencies of cytokine producing CD4+ T cells (CP=23, INF=25, UN=15). Briefly, whole blood was diluted 1:1 with RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/100 mg/ml), L-glutamine (2 mM), and HEPES (10 mM) (all from Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and placed in 12-well tissue culture plates (Costar, Corning Inc., NY, USA). The cultures were then stimulated with BmA, Mf, PPD, PMA/ionomycin (P/I) or media alone in the presence of the co-stimulatory reagent, CD49d/CD28 (BD Biosciences) at 37° C for 6 hrs. FastImmune Brefeldin A Solution (10 μg/ml) (BD Biosciences) was added after 2 hours. After 6 hours, whole blood was centrifuged, washed with cold PBS, and then 1x FACS lysing solution (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) was added. The cells were fixed using cytofix/cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), cryopreserved, and stored at −80°C until use. For cytokine neutralization experiments, whole blood from a separate set of CP (n=10) individuals was cultured in the presence of anti-IL-4 (5 μg/ml) or anti-TGFβ (5 μg/ml) or anti-IL-1R (2.5 μg/ml) or anti-IL-6R (2.5 μg/ml) or isotype control antibody (5 μg/ml) (R& D Sytems) for 18 h following which BmA was added and cultured for a further 6 h.

Intracellular cytokine staining

The cells were thawed and washed with PBS first and PBS/1% BSA later and then stained with surface antibodies for 30–60 minutes. Surface antibodies used were CD3 -Amcyan, CD4 - APC-H7 and CD8 - PE-Cy7 (all from BD Biosciences). The cells were washed and permeabilized with BD Perm/Wash™ buffer (BD Biosciences) and stained with intracellular cytokines for an additional 30 min before washing and acquisition. Cytokine antibodies used were IL-4 FITC and IL-10 APC (BD Pharmingen) and IL-9 PE (e-Biosciences). Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer with FACSDiva software v.6 (Becton Dickinson). The lymphocyte gating was set by forward and side scatter and 100,000 gated lymphocyte events were acquired. Data were collected and analyzed using Flow Jo software. All data are depicted as frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing cytokine(s) or as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cytokine expression within a particular subset. Values following media stimulation are depicted as baseline frequency while frequencies following stimulation with antigens or PMA/ionomycin are depicted as net frequencies (with baseline values subtracted).

ELISA

Whole blood cell cultures were also performed to measure IL-9 production. Briefly, whole blood from a separate set of CP (n=14) and INF (n=14) individuals was cultured in 12-well tissue culture plates for 72 h in the presence of BmA or PPD and culture supernatants collected. IL-9 ELISA (eBiosciences) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Geometric means (GM) were used for measurements of central tendency. Statistically significant differences between the groups were analyzed by using the Mann-Whitney test followed by Holm’s correction for multiple comparisons and differences within the same group were determined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman rank test.

Results

Identification of IL-9 and IL-10 co – expressing cells and their expansion following PPD and PMA/ionomycin stimulation

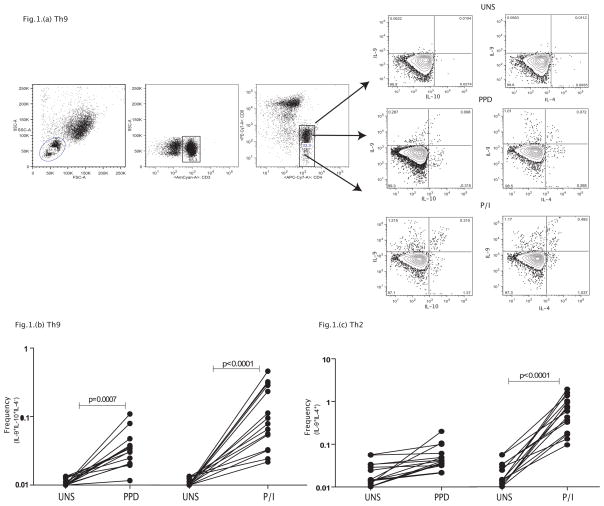

To determine if Th9 cells (defined as IL-9+, IL-10+ and IL-4−) are present in normal individuals, we measured the frequency of these cells in a group of normal individuals at baseline and following stimulation with a standard antigen (PPD) and a mitogenic stimulus (PMA/ionomycin). As shown in a representative contour plot (Figure 1A), we were able to detect Th9 cells co – expressing IL-9 and IL-10 in normal individuals. As shown in Figure 1B, this population exhibits significant expansion in response to PPD (3 fold) and PMA/ionomycin (8.5 fold) stimulation. IL-9 expression on CD4+ T cells was also detected in Th2 cells (expressing IL-9 and IL-4) and a similar expansion was observed following PPD (2.5 fold) and PMA/ionomycin (25.5 fold) stimulation (Figure 1C). Thus, Th9 cells, similar to their murine counterparts, are antigen and mitogen – responsive.

Figure 1. Identification of classical Th9 cells and their expansion in normal individuals.

(A) A representative flow plot depicting the gating strategy and baseline as well as PPD and PMA/ionomycin stimulated population of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9, IL-4 and IL-10 in a normal individual. (B) Baseline, PPD and PMA/ionomycin induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4 (classical Th9 cells) in normal individuals (n=15). (C) Baseline, PPD and PMA/ionomycin induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-4 (Th2 cells) in normal individuals (n=15). The data are represented as frequencies of CD4+ T cells and each line represents a single individual. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Increased frequencies of filarial – antigen stimulated Th9 cells and elevated IL-9 production in filarial lymphedema

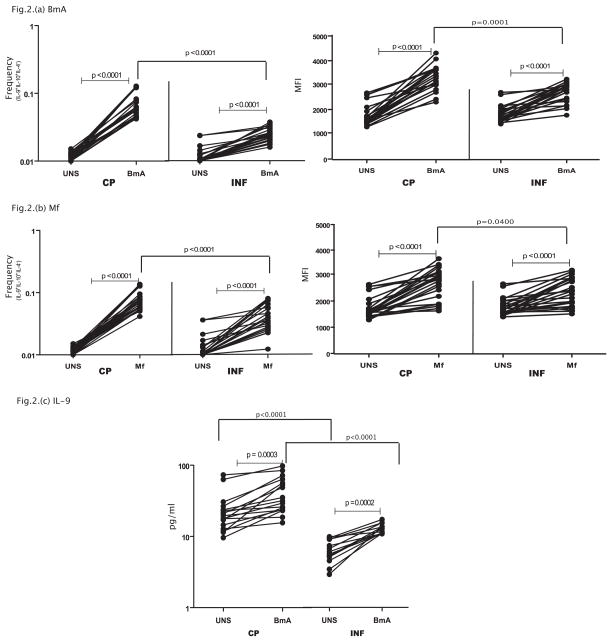

To determine the expression of Th9 cells in an infectious disease with an inflammatory component, we measured the frequency of Th9 cells in CP and compared them to INF individuals. As shown in Figure 2A, while parasite – antigen (BmA) induces expansion of Th9 cells in both CP and IN individuals, those with filarial lymphedema (CP) exhibited a significantly greater expansion of classical Th9 cells (IL-9+, IL-10+, IL-4−) in response to BmA (1.8 fold) in comparison to INF individuals. In addition, the per cell expression of IL-9 expression (based on MFI) on Th9 cells was also significantly increased following BmA stimulation in both groups but this enhancement was significantly greater (1.3 fold) in CP compared to INF individuals. Similarly, as shown in Figure 2B, both the frequencies of Th9 cells (2 fold) as well as the MFI of IL-9 expression (1.2 fold) on these cells was significantly higher in CP compared to INF individuals in response to a second filarial antigen, Mf. In addition, CP individuals did not exhibit any significant difference in the frequency of Th9 cells in response to PPD or PMA/Ionomycin when compared to INF individuals (data not shown). Moreover, filarial antigen induced net frequencies of Th9 cells were significantly higher in CP compared to normal, uninfected individuals as well (data not shown), indicating that heightened expansion of Th9 cells is specific to individuals with pathology. Finally, as shown in Figure 2C, CP individuals exhibit significantly elevated production of IL-9 in whole blood supernatants in response to BmA (GM of 11.7 pg/ml in CP vs. 6.4 in INF) but not PPD (data not shown) in comparison to INF individuals. Thus, filarial lymphatic disease is associated with enhanced antigen – driven frequencies of Th9 cells as well as increased production of IL-9 both on a per cell basis and in bulk populations.

Figure 2. Filarial lymphedema is associated with elevated frequencies of filarial antigen induced classical Th9 cells with increased IL-9 production.

(A) Filarial antigen (BmA) induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4 (classical Th9 cells) in CP (n=23) and INF (n=25) individuals and the mean fluorescence intensity of IL-9 expression on Th9 cells. (B) Filarial antigen (Mf) induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4 (classical Th9 cells) in CP (n=23) and INF (n=25) individuals and the mean fluorescence intensity of IL-9 expression on Th9 cells. (C) Filarial antigen (BmA) induced total levels of IL-9 whole blood culture supernatants in CP (n=14) and INF (n=14) individuals. The data are represented as frequencies and MFI of CD4+ T cells or levels of cytokine in the supernatants and each line represents a single individual. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the Mann-Whitney test.

Decreased frequencies of filarial – antigen stimulated Th2 cells expressing IL-9 in filarial lymphedema

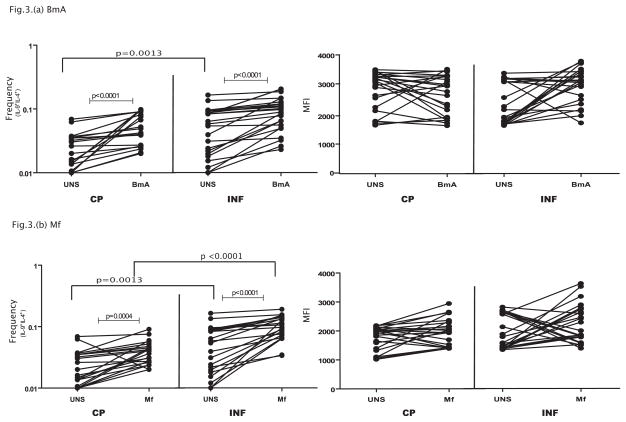

Since IL-9 is also expressed by conventional Th2 cells, we measured the frequency of IL-9+Th2 cells in CP and compared them to INF individuals. As shown in Figure 3A, while parasite – antigen (BmA) induces expansion of Th2 cells expressing IL-9 in both CP and INF individuals, those with filarial lymphedema (CP) exhibited a significantly lower expansion of Th2 cells expressing IL-9 (IL-9+, IL-4+) in response to BmA (1.5 fold) in comparison to INF individuals. However, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IL-9 expression on gated IL-9+, IL-4+ cells was not significantly altered following BmA stimulation in either group studied. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3B, the frequencies of IL-9+Th2 cells expressing IL-9 was significantly lower in CP compared to INF individuals in response to Mf (1. 7 fold) where as the per cell production of IL-9 in Th2 cells upon Mf stimulation was not significantly different between the groups. In addition, CP individuals did not exhibit any significant differences in the frequency of Th2 cells expressing IL-9 in response to PPD or PMA/Ionomcyin when compared to INF individuals (data not shown). Thus, filarial lymphatic disease is associated with diminished antigen – driven frequencies of IL9+Th2 cells expressing IL-9 suggesting that Th2 cells are not associated with pathology in filarial infections even if they co – express IL-9.

Figure 3. Filarial lymphedema is associated with diminished frequencies of filarial antigen induced Th2 cells co – expressing IL-9.

(A) Filarial antigen (BmA) induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-4 (Th2 cells) in CP (n=23) and INF (n=25) individuals and the mean fluorescence intensity of IL-9 expression on Th2 cells. (B) Filarial antigen (Mf) induced frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-9 and IL-4 (Th2 cells) in CP (n=23) and INF (n=25) individuals and the mean fluorescence intensity of IL-9 expression on Th2 cells. The data are represented as frequencies and MFI of CD4+ T cells and each line represents a single individual. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the Mann-Whitney test.

Positive relationship between the frequency of classical Th9 cells and the grade of pathology in filarial lymphedema

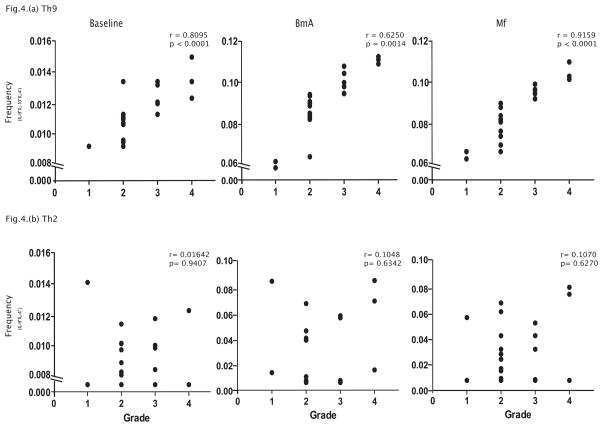

To determine the relationship between Th9 cells and IL-9+Th2 cells with the severity of filarial disease, we measured the frequencies Th9 cells and IL-9+Th2 and related them to the grade of lymphedema (according to the WHO classification) in the CP individuals. As shown in Figure 4A, we observed a significant positive correlation of Th9 cells at baseline (r=0.81, p<0.0001) and following BmA (r=0.62, p=0.0014) or Mf (r=0.92, p<0.0001) stimulation with the grade of lymphedema in these individuals. In contrast (see Figure 4B), we observed no relationship between IL-9+Th2 cells expressing IL-9 at baseline (r=0.016) and following BmA (r=0.104) or Mf (r=0.107) stimulation with the grade of lymphedema in CP individuals. On the other hand, we also observed a significant correlation between baseline or antigen-induced IL-9 levels in whole blood supernatants with the degree of pathology (data not shown). Thus, we provide corroborative evidence for a potential role for Th9 cells in filarial disease pathogenesis.

Figure 4. Filarial lymphedema is associated with a positive correlation between the frequency of classical Th9 cells with the grade of lymphedema.

(A) Frequency of classical Th9 (IL-9+, IL-10+, IL-4−) cells at baseline and following BmA or Mf stimulation is associated with the grade of lymphedema in CP (n=23) individuals. (B) Frequency of Th2 cells expressing IL-9 at baseline and following BmA or Mf stimulation is not associated with the grade of lymphedema in CP (n=23) individuals. The data are depicted as scatter plots with each circle representing one CP individual. P values were calculated using the Spearman rank correlation.

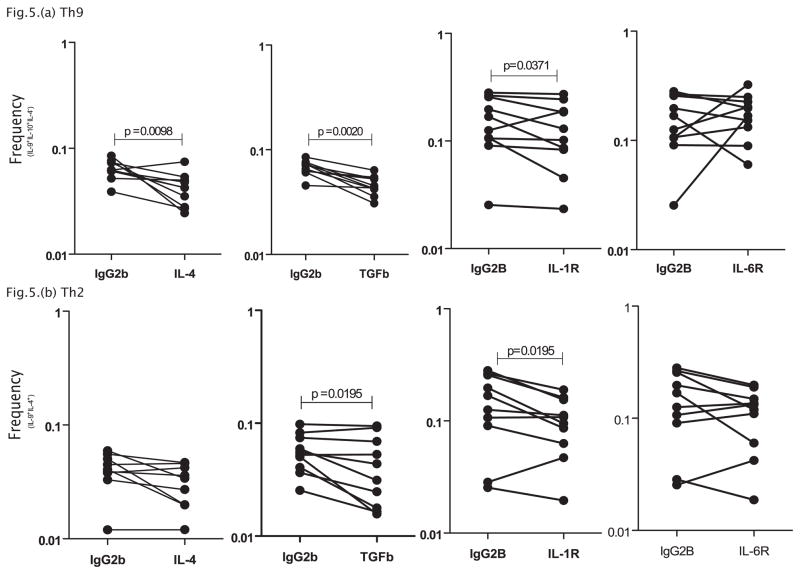

Blockade or IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1R but not IL-6R results in significantly decreased expansion of Th9 cells

Since IL-4 and TGFβ are known to be predominant cytokines inducing the generation of Th9 cells in murine systems, we investigated the role of IL-4 and TGFβ in modulating the frequency of Th9 cells. In addition, we also wanted to explore the role of IL-1 and IL-6, two cytokines known to play an active role in Th17 differentiation (23). To this end, we measured the frequency of Th9 cells and IL-9+Th2 cells in CP individuals (n=10) following in vitro neutralization of IL-4 or TGFβ or IL-1R or IL-6R and stimulation with BmA. As shown in Figure 5A, CP individuals exhibited significantly decreased net frequencies of Th9 cells (1.5 fold) following IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1R blockade but not following IL-6R blockade. Following cytokine blockade, only blockade of TGFβ and IL-1R (but not IL-4 and IL-6R) altered the frequencies of IL-9+Th2 cells (1.5 fold) (Figure 5B). Similar blockade of IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1 signaling resulted in diminished frequencies of Th9 cells in response to PPD in normal individuals (data not shown). Thus, IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1 all play a role in regulating the expansion of Th9 cells in vitro.

Figure 5. IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1 regulate the frequencies of classical Th9 cells in filarial lymphedema.

(A) IL-4, TGFβ and IL-1R but not IL-6R neutralization (with anti-IL-4, anti-TGFβ, anti-IL-R and anti-IL-6R respectively) significantly decreases the frequencies of classical Th9 cells (IL-9+, IL-10+, IL4−) following stimulation with BmA in CP individuals (n=10). (B) TGFβ and IL-1R but not IL-4 and IL-6R neutralization significantly decreases the frequencies of Th2 cells expressing IL-9 (IL-9+, IL-4+) following stimulation with BmA in CP individuals (n=10). Antigen – stimulated frequencies are shown as net frequencies with the baseline levels subtracted. Each line represents a single individual. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Discussion

Th9 cells are a recently discovered subset of CD4+ T cells, characterized by their unique ability to produce both IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4 (24, 25). The latter is considered to be the main distinguishing feature of Th9 cells since classical Th2 cells can also produce IL-9. In addition, innate lymphoid cells, commonly present at mucosal barriers are also major producers of IL-9 (2). Th9 cells are characteristically induced by IL-4 and TGFβ (3, 4) and express the transcription factors – PU.1 and interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) (26, 27). Th9 cells are important contributors to allergic inflammation, and Th9 cells differentiated from atopic patients secrete more IL-9 than those from nonatopic patients (12). Furthermore, allergic donors have substantially increased frequencies of Th9 cells than nonallergic donors (9). Th9 cells have also been shown to be present at increased frequencies in malignant pleural effusions (28) and in normal skin and blood of malignant melanoma patients (14). Thus, while Th9 cells are known to be involved in asthma (29), allergy (11), and anti-tumor responses (14, 30), the role of this CD4+ T subset in infectious diseases is not well-characterized. Th9 cells are known to be induced in pulmonary tuberculosis (31) but their role in host defense is not known. IL-9 is has also been shown to be associated with certain Th2 cell – mediated responses including mucus production from intestinal goblet cells and lung epithelial cells as well as intestinal and pulmonary mastocytosis (15, 32). Mice with systemic overexpression of IL-9 develop intestinal mastocytosis and enhanced production of serum IgE and are resistant to intestinal infection by the helminth parasite Trichuris muris (15). In addition, IL-9 blockade prevents worm expulsion and blood eosinophilia in mice infected with the same helminth (16).

Our study reveals certain interesting features of IL-9 producing CD4+ T cells in humans. First, by using multi-parameter flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining, we demonstrate the presence of a CD4+ T cell subset expressing both IL-9 and IL-10 but not IL-4, which we designated as Th9 cells, since this subset resembles the Th9 cells described in mice. Second, we demonstrate that IL-9 is also produced by a different subset of CD4+ T cells which also express IL-4 but not IL-10, that are by definition Th2 cells. Third, we demonstrate that both these CD4+ T cell subsets expand in frequency following stimulation with a common antigen as well as polyclonal stimulation. While the relative frequencies of Th9 cells as detected in our study is quite low, this is not very different from ex vivo frequencies of these cells observed in other studies (8, 9). To our knowledge, this is the first study in humans to characterize this precise CD4+ helper T cell subset in helminth infections.

Lymphatic filariasis is characterized by a diverse set of clinical manifestations including an asymptomatic (or subclinical) form seen among the majority of infected people (33). Although adaptive immune responses, especially T cell responses, are clearly important in the progression of asymptomatic infection to overt filarial disease, the nature of these T cell responses are still poorly characterized (17). Dysregulation of CD4+ T cell mediated immune activation, however, can lead to the development of tissue inflammation and pathology. Expansion of (or lack of suppressed) antigen-driven Th1 type CD4+ T cells have long been considered to be the hallmark of chronic pathology in filariasis (17). More recently, the involvement of Th17 responses has also been implicated (19). Therefore, we sought to elucidate whether filarial-induced pathogenic reactions were associated with Th9 responses and to delineate the CD4+ T cell subsets expressing IL-9 in filarial infections (and in normal subjects), we examined the expression of IL-9 in CD4+ T cells in CP individuals and contrasted this with IL-9 expression in INF individuals. Th9 cells have been associated with the development of pathology during allergic inflammation and autoimmune disease (24, 25). We now provide direct evidence for an association between Th9 cells, IL-9 production and clinical pathology in the form of lymphedema and elephantiasis in filarial infections. Our data show that filarial pathology is characterized by an expanded frequency of Th9 cells but not IL-9+Th2 cells expressing IL-9. In fact, Th2 cells co – expressing IL-9 exhibit greatly diminished antigen – driven frequencies in filarial pathology suggesting that IL-9 expression alone is not a characteristic feature of filarial disease. Rather, the presence of Th9 cells (with their capacity to secrete significantly increased amounts of IL-9 as characterized by both -9 production in whole blood supernatants and the per cell production of Th9 cells following antigen stimulation) appears to be the more important cellular feature associated with pathogenesis. This is further reinforced by the positive correlation observed between the Th9 cell percentages and the grade of lymphedema, which essentially reflects the severity of filarial disease. While the exact mechanism by which these Th9 cells potentially promote or exacerbate pathology remains to be determined, it is clear that filarial pathology is closely associated with the expansion of these cells as well as with elevated production of IL-9.

Although IL-4 and TGFβ have been described as the main inducers of Th9 differentiation in the mouse (3, 4), very few studies in humans has previously addressed the role of these cytokines in human Th9 differentiation (8, 34). Our study demonstrates a critical role for both IL-4 and TGFβ in driving the expansion of Th9 cells in filarial infections. Moreover, our data also reveal important clues on the regulation of Th9 cells versus Th2 cells co-expressing IL-9. While IL-4 was found to be necessary for Th9 induction, TGFβ was found to be necessary for the induction of both Th9 cells and Th2 cells co - expressing IL-9. Thus, we identify an important role for TGFβ in the expansion of IL-9 producing Th2 in filarial infections. IL-1 has been shown to be capable of inducing IL-9 expression under some conditions but its role in the differentiation of Th9 cells remains unclear (8, 35). Moreover, IL-1 synergizes with IL-6 in inducing differentiation of Th17 cells in humans (23). Hence, we also explored the role of IL-1 and IL-6 in the antigen – induced differentiation of Th9 cells in CP individuals. Interestingly, we found that IL-1 but not IL-6 was involved in the expansion of Th9 cells as well in mediating the expression of IL-9 in Th2 cells. Thus, we have uncovered a novel cytokine pathway influencing the expansion and/or differentiation of Th9 cells and IL-9+Th2 cells, involving the IL-1 family.

Our finding that Th9 responses are induced in patients with filarial pathology has clear implications. IL-9 is known to play a major role in protection against and expulsion of intestinal helminths (15) but IL-9 also participates in the pathogenic processes of allergy and asthma (24, 25). Moreover, Th9 cells per se have been shown to promote pathogenic processes and induce pathology in several autoimmune disease models in mice (24, 25). The mechanism by which Th9 cells promote pathology is not known, although it is speculated to depend on the effect of IL-9 on promoting inflammatory responses in target cells, including epithelial cells and mast cells (2). Our findings implicate a potential pathogenic role for Th9 cells in filarial disease. Our findings also suggest that strategies designed to block IL-9 or its downstream targets could potentially play a major role in amelioration of disease in lymphatic filariasis. In conclusion, we report an important association of Th9 cells with pathology in filarial infections and demonstrate a role for IL-4/TGFβ/IL-1 in the regulation of this CD4+ T cell subset.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Filariasis Clinic, Government General Hospital, Chennai, India, especially Drs. Sathiswaran and Yegneshwaran, as well as the NIRT Epidemiology Unit for their assistance with patient recruitment.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Because T.B.N., and S.B. are government employees and this is a government work, the work is in the public domain in the United States. Notwithstanding any other agreements, the NIH reserves the right to provide the work to PubMed Central for display and use by the public, and PubMed Central may tag or modify the work consistent with its customary practices. You can establish rights outside of the U.S. subject to a government use license.

Footnotes

Author disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Noelle RJ, Nowak EC. Cellular sources and immune functions of interleukin-9. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nri2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilhelm C, Turner JE, Van Snick J, Stockinger B. The many lives of IL-9: a question of survival? Nat Immunol. 2012;13:637–641. doi: 10.1038/ni.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Kwon H, Galileos G, Gao W, Sobel RA, Mitsdoerffer M, Strom TB, Elyaman W, Ho IC, Khoury S, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(−) effector T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veldhoen M, Uyttenhove C, van Snick J, Helmby H, Westendorf A, Buer J, Martin B, Wilhelm C, Stockinger B. Transforming growth factor-beta ‘reprograms’ the differentiation of T helper 2 cells and promotes an interleukin 9-producing subset. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1341–1346. doi: 10.1038/ni.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan MH. Th9 cells: differentiation and disease. Immunol Rev. 2013;252:104–115. doi: 10.1111/imr.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu LF, Lind EF, Gondek DC, Bennett KA, Gleeson MW, Pino-Lagos K, Scott ZA, Coyle AJ, Reed JL, Van Snick J, Strom TB, Zheng XX, Noelle RJ. Mast cells are essential intermediaries in regulatory T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2006;442:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowak EC, Weaver CT, Turner H, Begum-Haque S, Becher B, Schreiner B, Coyle AJ, Kasper LH, Noelle RJ. IL-9 as a mediator of Th17-driven inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1653–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beriou G, Bradshaw EM, Lozano E, Costantino CM, Hastings WD, Orban T, Elyaman W, Khoury SJ, Kuchroo VK, Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. TGF- beta induces IL-9 production from human Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2012;185:46–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones CP, Gregory LG, Causton B, Campbell GA, Lloyd CM. Activin A and TGF-beta promote T(H)9 cell-mediated pulmonary allergic pathology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1000–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao W, Zhang Y, Jabeen R, Nguyen ET, Wilkes DS, Tepper RS, Kaplan MH, Zhou B. Interleukin-9 Is Required for Allergic Airway Inflammation Mediated by the Cytokine TSLP. Immunity. 2013;38:360–362. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soroosh P, Doherty TA. Th9 and allergic disease. Immunology. 2009;127:450–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao W, Tepper RS, Kaplan MH. Predisposition to the development of IL-9-secreting T cells in atopic infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1357–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouyang H, Shi Y, Liu Z, Feng S, Li L, Su N, Lu Y, Kong S. Increased interleukin9 and CD4+IL-9+ T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol Med Report. 2013;7:1031–1037. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purwar R, Schlapbach C, Xiao S, Kang HS, Elyaman W, Jiang X, Jetten AM, Khoury SJ, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kuchroo VK, Clark RA, Kupper TS. Robust tumor immunity to melanoma mediated by interleukin-9-producing T cells. Nat Med. 2012;10:1038. doi: 10.1038/nm.2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faulkner H, Humphreys N, Renauld JC, Van Snick J, Grencis R. Interleukin-9 is involved in host protective immunity to intestinal nematode infection. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2536–2540. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard M, Grencis RK, Humphreys NE, Renauld JC, Van Snick J. Anti-IL-9 vaccination prevents worm expulsion and blood eosinophilia in Trichuris muris-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:767–772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babu S, Nutman TB. Immunopathogenesis of lymphatic filarial disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:847–861. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nutman TB, Kumaraswami V, Ottesen EA. Parasite-specific anergy in human filariasis. Insights after analysis of parasite antigen-driven lymphokine production. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1516–1523. doi: 10.1172/JCI112982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babu S, Bhat SQ, Pavan Kumar N, Lipira AB, Kumar S, Karthik C, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Filarial lymphedema is characterized by antigen-specific Th1 and th17 proinflammatory responses and a lack of regulatory T cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elyaman W, Bradshaw EM, Uyttenhove C, Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Imitola J, Bettelli E, Oukka M, van Snick J, Renauld JC, Kuchroo VK, Khoury SJ. IL-9 induces differentiation of TH17 cells and enhances function of FoxP3+ natural regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812530106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lal RB, Ottesen EA. Enhanced diagnostic specificity in human filariasis by IgG4 antibody assessment. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1034–1037. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ. Th17 cell differentiation: the long and winding road. Immunity. 2008;28:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabeen R, Kaplan MH. The symphony of the ninth: the development and function of Th9 cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan C, Gery I. The unique features of Th9 cells and their products. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32:1–10. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v32.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang HC, Sehra S, Goswami R, Yao W, Yu Q, Stritesky GL, Jabeen R, McKinley C, Ahyi AN, Han L, Nguyen ET, Robertson MJ, Perumal NB, Tepper RS, Nutt SL, Kaplan MH. The transcription factor PU.1 is required for the development of IL-9-producing T cells and allergic inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ni.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staudt V, Bothur E, Klein M, Lingnau K, Reuter S, Grebe N, Gerlitzki B, Hoffmann M, Ulges A, Taube C, Dehzad N, Becker M, Stassen M, Steinborn A, Lohoff M, Schild H, Schmitt E, Bopp T. Interferon-regulatory factor 4 is essential for the developmental program of T helper 9 cells. Immunity. 2010;33:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye ZJ, Zhou Q, Yin W, Yuan ML, Yang WB, Xiong XZ, Zhang JC, Shi HZ. Differentiation and Immune Regulation of IL-9-Producing CD4+ T Cells in Malignant Pleural Effusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1168–1179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1307OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xing J, Wu Y, Ni B. Th9: a new player in asthma pathogenesis? J Asthma. 2011;48:115–125. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.554944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Y, Hong S, Li H, Park J, Hong B, Wang L, Zheng Y, Liu Z, Xu J, He J, Yang J, Qian J, Yi Q. Th9 cells promote antitumor immune responses in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4160–4171. doi: 10.1172/JCI65459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye ZJ, Yuan ML, Zhou Q, Du RH, Yang WB, Xiong XZ, Zhang JC, Wu C, Qin SM, Shi HZ. Differentiation and recruitment of Th9 cells stimulated by pleural mesothelial cells in human Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Townsend JM, Fallon GP, Matthews JD, Smith P, Jolin EH, McKenzie NA. IL-9-deficient mice establish fundamental roles for IL-9 in pulmonary mastocytosis and goblet cell hyperplasia but not T cell development. Immunity. 2000;13:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nutman TB, Kumaraswami V. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis: perspectives on acute and chronic infection with Wuchereria bancrofti in South India. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:389–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong MT, Ye JJ, Alonso MN, Landrigan A, Cheung RK, Engleman E, Utz PJ. Regulation of human Th9 differentiation by type I interferons and IL-21. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:624–631. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramming A, Druzd D, Leipe J, Schulze-Koops H, Skapenko A. Maturation-related histone modifications in the PU.1 promoter regulate Th9-cell development. Blood. 2012;119:4665–4674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-392589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]