Key Points

CD4+ T cells are orchestrators, regulators and direct effectors of antiviral immunity.

Neutralizing antibodies provide protection against many viral pathogens, and CD4+ T cells can help B cells to generate stronger and longer-lived antibody responses.

CD4+ T cells help antiviral CD8+ T cells in two main ways: they maximize CD8+ T cell population expansion during a primary immune response and also facilitate the generation of virus-specific memory CD8+ T cell populations.

In addition to their helper functions, CD4+ T cells contribute directly to viral clearance. They secrete cytokines with antiviral activities and, in some circumstances, can eliminate infected cells through cytotoxic killing.

Memory CD4+ T cells provide superior protection during re-infection with a virus. Compared with new effector CD4+ T cells, memory CD4+ T cells have enhanced helper and effector functions and can rapidly trigger innate immune defence mechanisms early in the infection.

Subject terms: Immunology, Viral infection

Immunity to viruses is typically associated with the development of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. However, CD4+ T cells are also important for protection during viral infection. Here, the authors describe the various ways in which different CD4+T cell subsets can contribute to the antiviral immune response.

Abstract

Viral pathogens often induce strong effector CD4+ T cell responses that are best known for their ability to help B cell and CD8+ T cell responses. However, recent studies have uncovered additional roles for CD4+ T cells, some of which are independent of other lymphocytes, and have described previously unappreciated functions for memory CD4+ T cells in immunity to viruses. Here, we review the full range of antiviral functions of CD4+ T cells, discussing the activities of these cells in helping other lymphocytes and in inducing innate immune responses, as well as their direct antiviral roles. We suggest that all of these functions of CD4+ T cells are integrated to provide highly effective immune protection against viral pathogens.

Main

Viruses can enter the body by diverse routes, infect almost every type of host cell and mutate to avoid immune recognition. Destroying rapidly dividing viruses efficiently requires the coordination of multiple immune effector mechanisms. At the earliest stages of infection, innate immune mechanisms are initiated in response to the binding of pathogens to pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), and this stimulates the antiviral activities of innate immune cells to provide a crucial initial block on viral replication. Innate immune responses then mobilize cells of the adaptive immune system, which develop into effector cells that promote viral clearance.

Activation through PRRs causes professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to upregulate co-stimulatory molecules and promotes the migration of these cells to secondary lymphoid organs. Here, they present virus-derived peptides on MHC class II molecules to naive CD4+ T cells and deliver co-stimulatory signals, thereby driving T cell activation. The activated CD4+ T cells undergo extensive cell division and differentiation, giving rise to distinct subsets of effector T cells (Box 1). The best characterized of these are T helper 1 (TH1) and TH2 cells, which are characterized by their production of interferon-γ (IFNγ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4), respectively1. Specialized B cell helpers, known as follicular helper T (TFH) cells, and the pro-inflammatory TH17 cell subset also develop, along with regulatory T (TReg) cells, which are essential for avoiding over-exuberant immune responses and associated immunopathology2.

A key role of CD4+ T cells is to ensure optimal responses by other lymphocytes. CD4+ T cells are necessary as helpers to promote B cell antibody production and are often required for the generation of cytotoxic and memory CD8+ T cell populations. Recent studies have defined additional roles for CD4+ T cells in enhancing innate immune responses and in mediating non-helper antiviral effector functions. We discuss what is known about the T cell subsets that develop following acute viral infection and how different subsets contribute to viral control and clearance.

Following a rapid and effective antiviral response, infection is resolved and the majority of effector CD4+ T cells die, leaving a much smaller population of memory CD4+ T cells that persists long-term3,4. Memory CD4+ T cells have unique functional attributes and respond more rapidly and effectively during viral re-infection. A better understanding of the functions of memory CD4+ T cells will allow us to evaluate their potential contribution to immunity when they are induced by either infection or vaccination. We describe the antiviral roles of CD4+ T cells during the first encounter with a virus and also following re-infection.

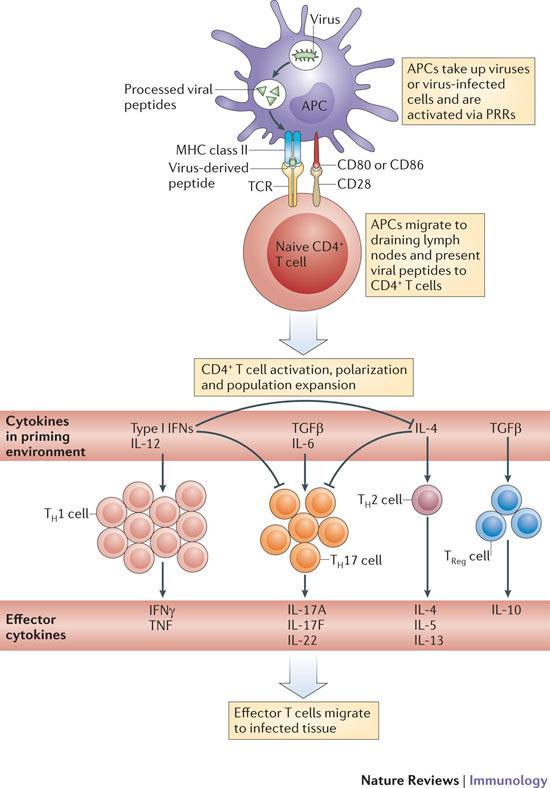

Generation of antiviral CD4 + T cells

To develop into effector populations that combat viral infections, naive CD4+ T cells need to recognize peptide antigens presented by MHC class II molecules on activated APCs. PRR-mediated signalling activates APCs to upregulate their expression of MHC class II molecules, co-stimulatory molecules (such as CD80 and CD86) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as type I IFNs, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1, IL-6 and IL-12)5. When the activated APCs migrate to draining lymph nodes, they prime naive virus-specific CD4+ T cells, which then differentiate into antiviral effectors (Fig. 1). The priming environment can vary dramatically during different viral infections and is influenced by many variables, including the route of infection, the viral dose and the organ or cell types targeted. As has been extensively reviewed elsewhere, the extent of T cell proliferation and the determination of T cell subset specialization are affected by the specific subset of APCs that is activated6,7, the antigen load and the duration of antigen presentation8, and the patterns and amounts of cytokines produced by different APCs9.

Figure 1. Generation of antiviral effector CD4+ T cells.

The crucial initial steps in generating primary antiviral T cell responses are the uptake of viral antigens by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in infected tissue, the activation of APCs by pattern-recognition receptor (PRR) ligation, and the migration of these cells to draining lymph nodes. The nature of the viral infection, as well as PRR ligation, can influence the activation status of antigen-bearing APCs and the T helper (TH) cell-polarizing environment. The recognition of antigens on activated APCs by naive T cells during viral infection predominately results in the generation of TH1 cells owing to the presence of type I interferons (IFNs) and interleukin-12 (IL-12). However, TH17, TH2 and regulatory T (TReg) cell populations are also generated to some degree in certain viral infections. TCR, T cell receptor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Effector T H cell subsets in viral infection

In contrast to TH cell populations that are generated in vitro, effector T cells that are found in vivo are often characterized by plasticity and heterogeneity in terms of their cytokine-producing potential. Nevertheless, the CD4+ T cells that are generated in response to viral infection mainly have a TH1-type phenotype and produce large amounts of IFNγ and express T-bet. This phenotype classically depends on the exposure of T cells to high levels of IL-12, type I IFNs and IFNγ in the priming milieu10, although TH1 cell responses are generated in response to certain viruses independently of IL-12 or type I IFNs11,12,13, suggesting that other factors can also contribute to TH1 cell polarization. IL-12 and type I IFNs promote TH1 cell differentiation both directly and indirectly (by repressing the development of other TH cell subsets), and can even influence effector T cells that are already polarized. For example, polarized TH2 cells that were transferred to hosts infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) acquired a mixed TH1/TH2 cell phenotype, which was characterized by high levels of IFNγ production and diminished IL-4 production. Interestingly, most IFNγ-producing cells in the TH1/TH2 cell population co-produced IL-4 or IL-13, and IL-12 and type I IFNs were shown to drive this mixed TH1/TH2 cell phenotype14. In vivo, IL-12 can also reprogramme in vitro-polarized TH17 cells to a TH1-type phenotype15,16.

Originally, it was thought that IL-4-producing TH2 cells were needed to drive optimal humoral immune responses. Thus, the predominance of TH1 cells over TH2 cells during viral infection was somewhat surprising, given the important role of neutralizing antibodies in viral clearance and in providing long-term immunity to re-infection. However, adoptive transfer of either TH1 cells or TH2 cells was shown to provide efficient help for the generation of neutralizing antiviral IgG responses17,18. The signature TH1-type cytokine, IFNγ, enhances IgG2a class switching, and this explains why IgG2a is usually the dominant isotype in IgG responses generated against viruses19. In fact, several studies have found that, far from promoting antiviral responses, TH2 cell-associated mediators (and IL-4 in particular) have a strong negative impact on immune protection and drive immunopathology during infection with many viruses, including influenza virus20,21, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)22, herpes simplex virus (HSV)23 and vaccinia virus24. Instead, it is now clear that IL-4-producing TFH cells provide much of the help required for IgG1 production (see below).

The roles of TH17-type effector responses during viral infection are not well understood, but virus-specific IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells have been detected in mice following infection with mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV)25, HSV26, vaccinia virus27, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus28 or influenza virus16, although at levels lower than those of TH1 cells. The generation of polarized TH17 cells during viral infection has been correlated with high levels of IL-6 and may also be influenced by transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ)28. TH17 cells are implicated in driving harmful inflammation during autoimmunity, and IL-17 may contribute to immunopathology during responses against viruses, as demonstrated in studies using influenza virus or vaccinia virus27,29. However, in some cases, TH17 cells contribute to host protection against viruses16. One protective mechanism mediated by TH17 cells might be the promotion of enhanced neutrophil responses at sites of infection. IL-17 upregulates CXC-chemokines that promote neutrophil recruitment30, and neutrophils can contribute to protection against certain viruses, including influenza virus31. We expect that other roles for TH17 cells will be identified in future studies, as TH17 cells often produce significant levels of IL-21 and IL-22 in addition to IL-17 (Ref. 16). Although not extensively studied in viral systems, IL-22 production by TH17 cells could be involved in regulating the expression of defensins, and could also play an important part in tissue repair (reviewed in Ref. 32). IL-21 production may also regulate aspects of the innate immune response during viral infection. Moreover, IL-21 is involved in sustaining CD8+ T cell responses during chronic viral infection, as discussed below.

Roles of CD4 + T cells during primary infection

Although the best-studied pathways of CD4+ T cell-mediated help are those that promote antibody production by B cells, CD4+ T cells also enhance effector CD8+ T cell responses during certain viral infections and contribute to the maintenance of a functional memory CD8+ T cell pool (Fig. 2). Furthermore, effector CD4+ T cells regulate the inflammatory response and can directly mediate viral clearance.

Figure 2. Helper functions of CD4+ T cells.

a | The canonical function of CD4+ T cells is the provision of help for B cells in germinal centre formation, isotype switching and affinity maturation of antibody responses. Follicular helper T (TFH) cells are a specialized subset of CD4+ T cells that provide help to B cells through both cell–cell interactions (most notably CD40L– CD40 interactions) and the release of cytokines. The generation of neutralizing antibodies is a crucial component of protection against many viral pathogens and the goal of most vaccine strategies. b | The best-characterized pathway of CD4+ T cell-mediated help in the generation of CD8+ T cell effectors involves the provision of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and the activation, known as 'licensing', of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) via CD40L–CD40 interactions. It is often unclear whether CD4+ T cell-mediated help has a role in the initial generation of antiviral CD8+ T cell effector responses, presumably because viruses can trigger pattern-recognition receptors and independently activate APCs. However, a clear role for CD4+ T cell-mediated help in the generation of functional memory CD8+ T cells has been demonstrated during viral infection. Downregulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression on CD8+ T cells is a prominent feature of CD8+ T cells that have been helped and at least in part facilitates their robust recall response during secondary infection. BCR, B cell receptor; ICOS, inducible T cell co-stimulator; ICOSL, ICOS ligand; TCR, T cell receptor; TH, T helper.

CD4+ T cell-mediated help for B cells. Current licensed vaccines directed against viral pathogens are evaluated almost exclusively on their ability to generate strong neutralizing antibody responses. Antibody-mediated protection can be extraordinarily long-lived33, and neutralizing antibodies present at the time of pathogen encounter can prevent rather than combat infection, thereby achieving 'sterilizing' immunity. Thus, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms by which CD4+ T cells help B cells during viral infection in order to define what is required for effective vaccination (Fig. 2a). CD4+ T cells that enter B cell follicles and provide help to B cells, resulting in germinal centre formation, are now referred to as TFH cells. The generation and functions of TFH cells have been expertly reviewed elsewhere34,35, so we focus only on the roles of these cells during viral infection.

Following viral infection, the expression of SLAM-associated protein (SAP) by TFH cells is necessary to direct the formation of germinal centres36,37, where TFH cells promote the generation of B cell memory and long-lived antibody-producing plasma cells36,38. Thus, TFH cells are likely to be important for generating long-lived antibody responses and protective immunity to most, if not all, viruses. Indeed, CD4+ T cells have been shown to be required for the generation of optimal antibody responses following infection with coronavirus39, vaccinia virus40, yellow fever virus41 or vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)42. It is not yet clear how distinct cytokine-polarized CD4+ T cell subsets influence the B cell response during primary viral infection. One possibility is that distinct TH cell subsets, such as TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells, can each develop into TFH cells and provide efficient help for B cells. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study demonstrating that such polarized subsets can be reprogrammed to express TFH cell characteristics in vitro43. As different TH cell subsets have been associated with distinct antibody class-switching responses, the broad range of protective antibody isotypes that is often found in individuals with immunity to a virus favours such a model.

Several co-stimulatory ligands expressed by CD4+ T cells contribute to the promotion of B cell activation and antibody production. One notable ligand is CD40 ligand (CD40L). Interactions between CD40 (which is expressed on B cells) and CD40L (which is expressed on activated CD4+ T cells) are crucial for generating optimal humoral responses against several viral pathogens, including LCMV, Pichinde virus, VSV, HSV and influenza virus44,45,46. The expression of inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS) by TFH cells has also been shown to be important for germinal centre formation34, and ICOS expression is required for optimal induction of humoral responses against LCMV, VSV and influenza virus47. The roles during viral infection of other co-stimulatory molecules expressed by TFH cells are less clear. For example, OX40-deficient mice generate normal levels of class-switched antibodies during infection with LCMV, VSV or influenza virus48. Further studies are required to determine the importance of additional signals that pass between TFH cells and B cells in generating protective antibody responses during viral infection.

CD4+ T cell-mediated help for CD8+ T cells. The mechanisms by which CD4+ T cells promote CD8+ T cell effector and memory responses are less well understood than B cell help. As in B cell help, CD40L–CD40 interactions between CD4+ T cells and APCs are crucial (Fig. 2). One possible mechanism — the 'licensing' of APCs by CD4+ T cells — may be of only minor importance during viral infection, as APCs can be activated effectively by viruses through PRRs49,50, thus obviating the need for this process50,51,52. However, it is unclear whether APCs that are activated directly through PRRs are functionally similar to those licensed by CD4+ T cells53. An absence of CD4+ T cells has been shown to compromise the generation of primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses against vaccinia virus54 and HSV55 (and influenza virus in some, but not all, studies56,57,58), suggesting that the two modes of APC activation are distinct. Whether CD4+ T cell-mediated help is required for the generation of optimal antiviral CD8+ T cell responses probably depends on which elements of the innate immune response are triggered following infection by a virus and to what extent. For example, the strong type I IFN response that is induced by administration of polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) can bypass the otherwise obligate requirement for CD4+ T cell-mediated help in the generation of CD8+ T cell responses following vaccinia virus infection59.

It is not clear whether different TH cell subsets have distinct roles in helping CD8+ T cells. During the primary response, the licensing of APCs by CD4+ T cells probably occurs before the full polarization of effector CD4+ T cells, but fully polarized TH cells might also promote efficient CD8+ T cell responses against viral pathogens through mechanisms other than APC licensing. For example, chemokines produced following antigen-specific interactions between APCs and CD4+ T cells can actively attract CD8+ T cells to the activated APCs60, and CD40L–CD40 interactions between CD4+ T cells and APCs can protect APCs from CTL-mediated death61, perhaps leading to more-efficient CD8+ T cell priming.

In addition, CD4+ T cells facilitate the development of functional, pathogen-specific memory CD8+ T cells that can respond following re-infection51,52,62,63. One mechanism by which CD4+ T cells promote this process involves the downregulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression on responding CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2). It is thought that CD8+ T cells that are helped by CD4+ T cells downregulate TRAIL expression and become less susceptible64, or have delayed susceptibility65, to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. By contrast, CD8+ T cells that have not been helped undergo enhanced TRAIL-mediated apoptosis following antigen re-exposure. CD4+ T cell-mediated help also controls the expression of other molecules. For example, CD4+ T cells downregulate the expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) on CD8+ T cells, and this can enhance the function of pathogen-specific memory CD8+ T cells66,67,68.

CD4+ T cells may promote the generation of effector and memory CD8+ T cell populations through many possible pathways. One such pathway involves enhancing the APC-mediated production of cytokines that augment initial CD8+ T cell responses; these cytokines include IL-1, IL-6, TNF and IL-15 (Ref. 69). Paracrine IL-2 produced by CD4+ T cells during the initial priming of CD8+ T cells in LCMV infection dramatically improves the CD8+ T cell recall response potential70. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells have been shown to upregulate the expression of CD25 (also known as IL-2Rα) on CD8+ T cells during infection with vaccinia virus or VSV71. At later stages of the response, CD4+ T cells produce additional cytokines, such as IL-21, which appears to be a crucial signal for downregulating TRAIL expression on CD8+ T cells responding to vaccinia virus72. Finally, evidence suggests that direct ligation of CD40 on naive CD8+ T cells by CD40L on CD4+ T cells can enhance the generation of memory CD8+ T cells73 (Fig. 2).

CD4+ T cells seem to be particularly important for maintaining memory CD8+ T cell populations74, and the presence of CD4+ T cells during priming may influence the homing pattern and, ultimately, the tissue distribution of memory CD8+ T cells75. Whereas a specialized T cell subset (namely, TFH cells) provides help for B cells, no analogous helper subset for CD8+ T cells has been identified to date. Defining the conditions that lead to the generation of CD4+ T cells with potent CD8+ T cell helper activity could be important for developing better vaccines against several viral pathogens.

More than just lymphocyte helpers

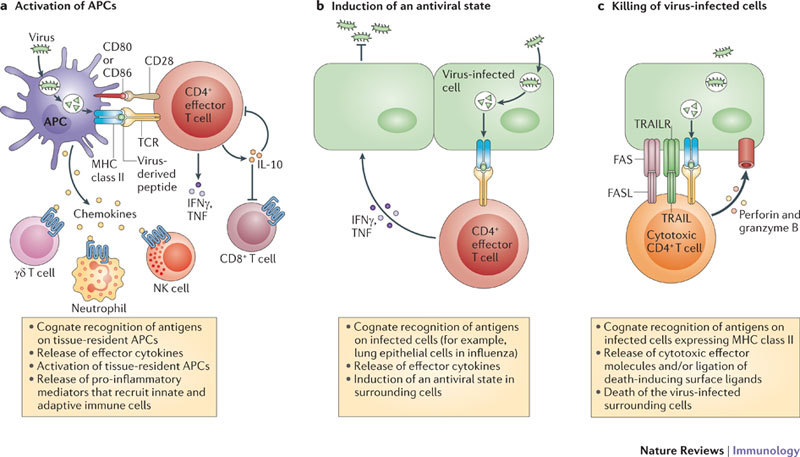

In addition to activating cells of the innate immune system and providing potent help to promote the functions of B cells and CD8+ T cells during viral infection, CD4+ T cells develop into populations of effector T cells that migrate to sites of infection76. Accumulating evidence suggests that effector CD4+ T cells have potent protective roles during viral infection that are independent of their helper activities. Strong immune protection mediated by CD4+ T cells has been described in animal models of infection by rotavirus77, Sendai virus78,79, gammaherpesviruses80,81, West Nile virus (WNV)82, HSV83,84, influenza virus85,86, dengue virus87, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus88, coronavirus89, VSV90 and Friend virus91,92. In many cases, the direct protective mechanism used by CD4+ T cells has not been defined. However, effector CD4+ T cells have, in general, been shown to protect against viral pathogens through two distinct mechanisms: first, through the production of cytokines, most notably IFNγ and TNF81,82,85,87,89,90,92; and second, through direct cytolytic activity78,81,82,87,92 mediated by both perforin and FAS (also known as CD95)84,86 (Fig. 3). Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells have also been observed following infection with LCMV93.

Figure 3. Antiviral functions of CD4+ T cells that are independent of their lymphocyte helper functions.

a | After migrating to sites of infection, effector CD4+ T cells that recognize antigens on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) produce an array of effector cytokines that contribute to the character of the inflammatory responses in the tissue. Some products of highly activated effector CD4+ T cells, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), dampen inflammation and regulate immunopathology, whereas others, such as interferon-γ (IFNγ), are pro-inflammatory and activate macrophages, which in turn drive further inflammation. The production of IL-10 by effector CD4+ T cells can have a profound impact on the outcome of a viral infection. b | IFNγ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and other cytokines produced by CD4+ T cells help to coordinate an antiviral state in infected tissues. c | Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells can directly lyse infected cells through diverse mechanisms, including FAS-dependent and perforin-dependent killing. FASL, FAS ligand; NK, natural killer; TCR, T cell receptor; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; TRAILR, TRAIL receptor.

The cytotoxic activity of CD4+ T cell effectors does not depend on TH1 cell polarization94, and expression of the transcription factor eomesodermin, but not T-bet, may be crucial in driving the development of cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in vivo95. Thus, CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic activity could be considered a separate functional T cell subset. The fact that MHC class II expression is largely restricted to professional APCs under steady-state conditions may limit the protective potential of virus-specific cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. However, cells other than professional APCs are capable of upregulating MHC class II expression following pathogen challenge and could therefore become targets of cytotoxic CD4+ T cells during viral infection. For example, epithelial cells that are activated by infection96 or IFNγ-mediated signals97 strongly upregulate their expression of MHC class II molecules.

Although immune protection mediated by cytotoxic CD4+ T cells requires direct recognition of virus-infected cells, soluble factors released by other effector CD4+ T cells can act more broadly. For example, IFNγ can promote the establishment of an antiviral state in surrounding tissue and can also activate several innate immune cell populations, most notably macrophages, to mediate antiviral activity98. Thus, effector CD4+ T cells that migrate to infected tissues probably promote viral clearance through both cytotoxic and cytokine-dependent mechanisms.

Immunoregulation by effector CD4 + T cells

Effector CD4+ T cells are capable of potent immunoregulation at sites of infection. A subset of TH1 cells has been found to transiently produce both IFNγ and IL-10 at the peak of the effector CD4+ T cell response in many models of infectious disease99. Several signals have been found to stimulate the generation of IL-10-producing effector CD4+ T cells, including high levels of antigen, soluble factors such as IL-12 and IL-27, and co-stimulatory signals such as ICOS (reviewed in Ref. 99). IL-10 is a pleiotropic cytokine that is most often associated with anti-inflammatory or inhibitory functions (Fig. 3). The impact of IL-10 production by effector CD4+ T cells is complicated and can be variable, especially in situations in which strong immune responses (which are capable of serious immunopathology) are required to eliminate a rapidly replicating pathogen. For instance, the absence of IL-10 during influenza virus infection can lead, on the one hand, to improved host survival, owing to enhanced T cell16 and antibody100 responses, but also, on the other hand, to exacerbated inflammation and immunopathology, which result in increased mortality101. Similarly, ablating Il10 has been found to enhance protection against WNV102 and vaccinia virus103, but to cause increased pathology following infection with RSV104 and death following infection with mouse hepatitis virus105 or coronavirus106. Finally, as well as producing IL-10 themselves, effector CD4+ T cells can also promote IL-10 production by effector CD8+ T cells during viral infection107.

Regulatory CD4 + T cells

Increased frequencies of CD4+ TReg cells (of both the forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+ and FOXP3− populations) have been observed in numerous human and animal studies of viral infection. Most studies that have assessed the impact of TReg cells during viral infection have concentrated on models of chronic infection. In such settings, TReg cells have been found, depending on the particular pathogen, to have both beneficial roles, such as limiting collateral tissue damage, and detrimental roles, including diminishing the overall magnitude of antiviral immune responses108. The antigen specificity of TReg cells in the context of infectious disease has not been addressed often, but it is likely that TReg cell populations contain at least some virus-specific cells and that these populations are generated in concert with antiviral effector T cell responses. Indeed, this has recently been shown in a coronavirus infection model109. The accumulation of virus-specific FOXP3+ TReg cells during viral infection could be due to the expansion of pre-existing populations of thymus-derived 'natural' TReg cells that are specific for viral antigens, or could also reflect the de novo generation of 'induced' TReg cells from naive virus-specific CD4+ T cells. An important factor in the generation of induced TReg cells appears to be TGFβ110,111, although how induced TReg cells affect viral infection is not yet well understood. For example, some viral pathogens may promote the development of TReg cell populations to limit the host antiviral response. Evidence for this hypothesis has been found in several models, mainly of chronic viral infection112,113. In acute viral infection, which has not been studied as fully as chronic infection, TReg cells have been shown to limit pathology during infection with WNV114 or RSV115,116 and in a model of influenza A virus infection117. A detailed account of TReg cell induction and responses during viral infection is available elsewhere118.

CD4 + T cells and chronic viral infection

Compared with our understanding of CD8+ T cells119, much less is known about how chronic infection affects CD4+ T cell phenotype and function. However, the impact of persistent viral infection on CD4+ T cell function and the importance of CD4+ T cells during chronic viral infection are receiving increasing attention. During persistent infection with LCMV clone 13, responding CD4+ T cells lose the ability to produce TH1-type effector cytokines and to function optimally following viral rechallenge120. The loss of function of CD4+ T cells responding to persistent antigen is probably driven by high levels of antigen following the priming phase121 and seems not to be regulated by the intrinsic changes in APCs that are caused by chronic viral pathogens120.

Chronic infection may not lead to irreversible exhaustion of responding CD4+ T cells. For example, functionally impaired CD4+ T cells have been observed in patients with HIV, and treatment with antibodies that stimulate CD28 (Ref. 122), block T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain protein 3 (TIM3)123 or block PD1 signalling124 dramatically increased the proliferative potential of these T cells in vitro. Also, a recent study by Fahey et al. found that during chronic LCMV infection responding CD4+ T cells progressively adopt a functional TFH cell phenotype125. That CD4+ T cells may retain specific functions during chronic infection helps to explain earlier observations that persistent LCMV infection is eventually cleared through mechanisms that are dependent on CD4+ T cells (Box 2). For instance, interactions between exhausted CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells may restore CD8+ T cell function during chronic infection with LCMV126. These findings and others (reviewed in Refs 127, 128) have important implications for the design of vaccines against viruses that cause chronic infection in humans (such as HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C).

Memory CD4 + T cell responses against viruses

Following the resolution of infection, or after successful vaccination, most virus-specific effector CD4+ T cells die. This leaves a small population of memory T cells, which ensures that the frequency of virus-specific T cells is greater than it was before priming. The population of CD4+ memory T cells diminishes with time and may require boosting. It is unclear which responding effector CD4+ T cells make the transition to a memory phenotype, but a recent study suggests that those with lower expression of LY6C and T-bet have a greater potential to do so129. A quantitative gain in antigen-specific cells represents one important advantage of the memory state, but memory T cells also differ from naive T cells by broad functional criteria. Compared with naive T cells, memory CD4+ T cells respond much faster, respond to lower antigen doses, require less co-stimulation and proliferate more vigorously following pathogen challenge130. In addition, subpopulations of memory CD4+ T cells have wider trafficking patterns and some are retained at or near sites of previous infection131, and this contributes to their ability to be rapidly activated following local re-infection. Tissue tropism and/or retention of tissue-resident memory CD4+ T cells may depend on specific interactions between adhesion molecules and their receptors (Box 3).

Memory CD4+ T cells enhance early innate immune responses following viral infection. Memory CD4+ T cell-mediated recognition of antigens presented by APCs following re-infection has rapid consequences. Within 48 hours of intranasal infection with influenza virus, antigen-specific memory CD4+ T cells cause an enhanced inflammatory response in the lung, and this is characterized by the upregulation of a wide array of pro-inflammatory mediators132 (Fig. 4). In infected tissues, transferred TH1-type and TH17-type memory cells, as well as memory CD4+ T cells generated by previous infections, upregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p40, CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10. By contrast, TH2-type and non-polarized (TH0) memory T cells have a minimal impact on pulmonary inflammation following influenza virus challenge. To induce innate inflammatory responses, memory CD4+ T cells must recognize antigens on CD11c+ APCs. These APCs become activated during interactions with memory CD4+ T cells, and this results in the upregulation of MHC class II and co-stimulatory molecule expression by the APCs. Activated APCs contribute to the subsequent innate inflammatory response through the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1β. By contrast, the naive CD4+ T cell response in vivo does not have an appreciable impact on the tissue inflammatory response at 48 hours post-infection132. In other studies, naive CD4+ T cells could actually downregulate tissue inflammation following mouse hepatitis virus infection133. The ability of TH1-type and TH17-type memory CD4+ T cells, but not TH2-type or non-polarized memory T cells, to promote an early inflammatory response may help to explain why transfer of virus-specific TH1 and TH17 effector cells, but not transfer of TH2 or non-polarized T cells, promotes early control of viral loads in mice infected with influenza virus16,86,132. A similar impact of memory CD4+ T cells on early viral control during secondary influenza infection was recently reported by Chapman et al.134, and this also correlated with a dramatic enhancement of innate immune responses against the virus. However, this effect has not yet been studied in other models of viral infection.

Figure 4. Activation of APCs through PRRs and through the recognition of antigens by memory CD4+ T cells.

a | Several classes of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), sense the presence of viral pathogens, and the triggering of these receptors leads to the activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells (DCs). Activated APCs upregulate their expression of MHC molecules and co-stimulatory molecules, which are important for the priming of naive virus-specific T cells. Triggering of PRRs at the site of infection induces local inflammation, which involves the activation of several populations of innate immune cells that can control viral titres and establish chemokine gradients to attract further antiviral effector cells. The efficiency of PRR triggering can determine whether viral replication or protective immunity gains the upper hand. b | Virus-specific memory CD4+ T cells can directly activate DCs through the recognition of antigens presented by MHC class II molecules, even in the absence of co-stimulation delivered via PRR-mediated signalling. The crucial signals delivered by memory CD4+ T cells to DCs in this process are unclear and could involve both cell-surface interactions and cytokine signals. The outcome of DC activation and the initiation of inflammatory responses are similar whether triggered through PRRs or memory CD4+ T cells but, in situations of infection with a rapidly replicating virus (such as influenza virus), memory CD4+ T cell-mediated enhancement of innate immunity is substantially quicker and more effective than that provided by PRR triggering. TCR, T cell receptor.

We suggest that the early activation of innate immune mechanisms by memory CD4+ T cells serves to lessen the 'stealth phase' of infection, during which titres of the virus are still too low to generate robust inflammatory responses135. This would prevent viruses from gaining a 'foothold' in the host by infecting and replicating in cells at a level that is below immune detection. Importantly, the induction of early innate immune responses by memory CD4+ T cells does not require PRR activation132 and could therefore be important for enhancing protection against viral pathogens — such as vaccinia virus and influenza virus — that can actively antagonize key components of innate recognition pathways, such as dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR)136.

One intriguing finding is that memory CD4+ T cells specific for ovalbumin enhance antiviral immunity when ovalbumin is co-administered with an influenza virus that does not express ovalbumin132. Thus, we hypothesize that the induction of innate immune responses by memory CD4+ T cells could have an adjuvant effect, which could be exploited (and substituted for PRR stimulation132) to promote immune responses to vaccines that do not contain live viruses. For example, a vaccine could activate the innate immune system through antigen-specific stimulation of memory CD4+ T cells that are known to be widespread in the human population (for example, most individuals have memory CD4+ T cells specific for tetanus toxin). This method could possibly enhance the immunogenicity of 'weak' vaccines.

Heterologous memory responses. Heterologous viral immunity occurs when memory T cells that were generated in response to a particular virus cross-react with epitopes expressed by other, unrelated viruses. It has recently become clear that this is quite a widespread phenomenon that is likely to be important in the human population, as humans are exposed to numerous antigens as a result of infection and vaccination137. Although heterologous immune responses can be protective, they may in some cases be deleterious and can result in dramatic immunopathology138. It will be important to determine to what extent the ability of memory CD4+ T cells to induce innate immunity contributes to both beneficial and deleterious heterologous responses.

Helper functions of memory CD4+ T cells. Several studies indicate that memory CD4+ T cells are superior to naive T cells in providing help for B cells, and they have been shown to promote earlier B cell proliferation, higher antibody levels and earlier class-switching responses compared with naive CD4+ T cells139,140,141. In many cases, when pre-existing circulating antibodies are able to recognize the virus, re-infection may never occur. Faster antibody production could be particularly important after re-infection with rapidly mutating viruses (such as influenza virus), as the generation of neutralizing antibodies specific for new variants that evade previously generated antibodies could be necessary for immunity.

That memory CD4+ T cells are superior helpers for B cells compared with naive T cells is suggested by multiple criteria, and many mechanisms may contribute. Memory CD4+ T cells contain preformed stores of CD40L, an important signal in CD4+ T cell-mediated help for antibody production142. The location of memory CD4+ T cells may also be an advantage. For example, antigen-specific memory CD4+ T cells with a TFH cell phenotype are retained in the draining lymph nodes of mice for over 6 months following immunization143. The increased levels and polarized profile of cytokines produced by memory CD4+ T cells, as compared with those of naive T cells, is likely to promote a more-robust B cell antibody response and to dictate the antibody isotype, which has a key role in the efficacy of antibodies specific for viruses such Ebola virus144, WNV145 and influenza virus146. Recent observations suggest that IL-4 and IFNγ produced by TFH cells have a central role in driving not only immunoglobulin class switching in the germinal centre, but also B cell affinity maturation147.

Whether memory CD4+ T cells are superior to naive CD4+ T cells at providing help for primary or secondary CD8+ T cell responses during viral infection has not been rigorously tested. However, the features of memory cells described here suggest that memory CD4+ T cells could promote an accelerated response by naive CD8+ T cells, both through more-rapid licensing of APCs and through faster and more-robust production of IL-2 and possibly other cytokines; these possibilities need to be explored. In support of this concept, a study using Listeria monocytogenes found that TH1-type but not TH2-type memory CD4+ T cells enhanced primary CD8+ T cell responses in terms of both magnitude and cytokine production, although the mechanism of memory CD4+ T cell-mediated help was not determined148. Whatever the pathways involved, the fact that memory CD4+ T cells enhance the generation of CD8+ T cell memory and that this process has a greater dependence on CD4+ T cell-mediated help when PRR stimulation is limited suggests that CD4+ T cell-mediated help will be of particular importance in achieving optimal CD8+ T cell memory responses with vaccines that do not contain live, replication-competent viruses.

Finally, we should point out that the impact of memory CD4+ T cells on the early innate immune response may also affect subsequent antigen-specific immune responses against viruses, owing to alterations in the expression of chemokines. For example, by upregulating local production of CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) ligands at the site of infection, memory CD4+ T cells can promote the recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells that contribute to early viral control in influenza virus infection149. In HSV-2 infection, IFNγ expression by CD4+ T cells is required to induce chemokines that recruit effector CD8+ T cells to the infected vaginal tissue150. Similar roles for CD4+ T cells in promoting CD8+ T cell recruitment may occur during infections with other viruses, although it is often difficult to separate the roles of CD4+ T cells in generating effector CD8+ T cells from their roles in modifying CD8+ T cell trafficking39,85,151.

Secondary effector T cells

The presence of memory CD4+ T cells that are capable of producing multiple cytokines has been correlated with superior protective capacity in numerous studies152, but how such cells achieve enhanced protection has not been addressed. One possibility is that 'secondary' effector CD4+ T cells that arise from memory precursors may be much more efficient in directly combating pathogens than primary effector CD4+ T cells that arise from naive cells. Our recent experiments that directly compared such primary and secondary effectors during influenza virus infection support such a view (T.M.S., K.K.M., L. M. Bradley and S.L.S., unpublished observations). We found that following adoptive transfer of either antigen-specific memory CD4+ T cells or an equal number of antigen-specific naive CD4+ T cell precursors, the secondary effector populations that developed from the memory CD4+ T cells showed greater expansion and contained higher frequencies of T cells that secrete multiple cytokines. Furthermore, although high levels of IL-10 were produced by primary effector CD4+ T cells during influenza virus infection, secondary effector cells produced much less IL-10. Thus, memory CD4+ T cells seem to give rise to secondary effector T cells that are distinct from and superior to the primary effectors derived from naive CD4+ T cells. We suggest that this results in more-protective recall responses, and we predict that further functions of secondary effectors will be discovered as additional comparative analyses are carried out.

Summary

Here, we have reviewed how CD4+ T cells contribute to protective immunity to viruses, during both primary and secondary infections. Several key principles emerge. Distinct CD4+ T cells subsets — including TH1 cells, TH17 cells, TFH cells and CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic functions — have important roles in the antiviral response. Key among these roles is the provision of help to B cells, but CD4+ T cells also contribute to the antiviral response by producing cytokines and chemokines, by enhancing CD8+ T cells responses and through direct cytotoxic effects on virus-infected cells.

Memory CD4+ T cells have additional protective functions compared with naive cells. They induce early innate inflammatory responses in the tissue that contribute to viral control. Importantly, memory CD4+ T cells provide more-rapid help to B cells, and probably to CD8+ T cells, thereby contributing to a faster and more-robust antiviral immune response. Finally, secondary effectors derived from memory CD4+ T cell precursors are likely to be more capable of mediating direct antiviral activity than primary effectors derived from naive CD4+ T cells.

The picture that emerges is one in which CD4+ T cells carry out an impressive variety of functions at different times and in different sites, and we suggest that the synergy of these distinct mechanisms can provide an extraordinarily high level of viral control. Depending on the particular pathogen and the level of infection, these mechanisms may often be redundant, but they are likely to each make key contributions following exposure to high doses of rapidly replicating viruses or to viruses that have evolved mechanisms to evade specific immune pathways. We point out that the study of the immune response to viral infections has revealed new mechanisms by which CD4+ T cells function to protect against pathogens, and we predict that additional mechanisms will be identified in the future. Thus, this area of study will lead to a better understanding of how vaccines can be designed to harness the power of CD4+ T cell memory.

Box 1 | Subsetting CD4+ T cell responses based on TH cell polarization.

Following recognition of a specific antigen presented by an appropriately activated antigen-presenting cell, naive CD4+ T cells undergo several rounds of division and can become polarized into distinct effector T helper (TH) cell subsets that differentially orchestrate protective immune responses (see the figure). The differentiation of polarized effector T cells is controlled by unique sets of transcription factors, the expression of which is determined by multiple signals but particularly by soluble factors that act on responding CD4+ T cells during their activation. The elucidation of the crucial cytokines that govern the differentiation of distinct TH cell subsets has allowed researchers to examine the protective capacities of differently polarized CD4+ T cell subsets in several models of infectious disease.

Although the production of the signature cytokines interferon-γ (IFNγ), interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-17 is routinely used to assign subsets (TH1, TH2 and TH17, respectively) to responding CD4+ T cells, it is increasingly clear that considerable plasticity exists within TH cell subsets in vivo, especially during responses to pathogens. Moreover, certain cytokines (for example, IL-10) can be produced by subpopulations of cells within multiple effector subsets. Finally, the successful clearance of viral pathogens in particular often depends on complex CD4+ T cell responses that encompass multiple TH cell subsets. Together, these T cell subsets are capable of mediating direct antiviral functions, of providing help for B cells, of regulating immunopathology and of mediating cytotoxic killing of virus-infected cells. CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic activity have been described in several models of viral disease as well as in the clinic. Following re-stimulation, memory CD4+ T cells retain their previous effector functions and rapidly produce effector cytokines. This property of primed CD4+ T cells represents a key advantage of the memory state.

Certain TH cell subsets — including follicular helper T (TFH) cells and regulatory T (TReg) cells — are often defined less by their cytokine profile and more by their functional attributes. Further studies will be required to determine whether populations of CD4+ T cells with specialized functions can include cytokine-polarized cells from several subsets.

BCL-6, B cell lymphoma 6; EOMES, eomesodermin, FASL, FAS ligand; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; GATA3, GATA-binding protein 3; RORγt, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-γt; TCR, T cell receptor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Box 2 | CD4+ T cell help for CD8+ T cells during chronic viral infection.

The best-characterized function of CD4+ T cells during persistent viral infection is the maintenance of competent CD8+ T cells that retain robust effector functions long-term153. Although this has been most-rigorously studied in models of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, CD4+ T cells have also been found to affect CD8+ T cell responses to varying degrees in other models of chronic infection, including mouse cytomegalovirus154, mouse polyomavirus155 and gammaherpesvirus156 infection. Recent studies using LCMV infection suggest that interleukin-21 (IL-21) production by CD4+ T cells during chronic infection is crucial for maintaining functional CD8+ T cells that are able to contain the infection157,158,159. Importantly, clinical evidence also correlates the presence of higher numbers of IL-21-producing CD4+ T cells with improved CD8+ T cell function and improved control of HIV infection160,161. These observations suggest new avenues that could improve vaccination strategies and adoptive transfer therapies162 through the generation of CD4+ T cell populations specifically geared towards the provision of maximal help in the context of chronic infection.

Box 3 | Tissue-resident memory T cells.

Following the resolution of primary immune responses, most effector T cells die by apoptosis, leaving behind a small population of long-lived memory cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that, in addition to recirculating through lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues, some memory cells reside at sites of infection. Although most of these studies have concentrated on CD8+ T cell memory, CD4+ T cells also appear to survive for long periods in peripheral tissues163,164.

Often, the expression of distinct surface proteins distinguishes tissue-specific memory cells from conventional lymphoid memory populations. These molecules are likely to have a crucial role in the retention of memory T cells at different sites through specific interactions with ligands that are expressed in particular tissues. For example, the expression of α1β1 integrin (also known as VLA1) by airway-resident memory CD4+ T cells in the lungs can facilitate binding to collagen164, and high levels of CD103 expression by brain- or skin-resident memory CD8+ T cells facilitates their interaction with cells that express E-cadherin165,166.

Tissue-resident memory T cells act as a first line of defence. Combined with the ability of memory T cells, but not naive T cells, to be activated through the recognition of antigens in peripheral tissues132,167, the location of memory CD4+ T cell populations at potential sites of re-infection represents a powerful advantage of the memory state over the naive state, in which a lag of several days precedes the influx of antigen-specific cells into infected sites. Tissue-resident memory cells may facilitate more-rapid recruitment and activation of innate cell populations that are capable of controlling initial viral titres. Moreover, these memory cells may simultaneously accelerate the development of pathogen-specific effector populations of B and T cells by promoting the earlier activation of antigen-presenting cells. Elucidating the important cues that drive the development of long-lived tissue-resident memory cells is likely to become an important area of research, especially as this understanding may lead to the design of improved vaccination strategies.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the many authors whose papers could not be cited owing to space limitations. We are grateful to R. W. Dutton for critical reading of the manuscript and insightful discussions. The authors are supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- Pattern-recognition receptors

(PRRs). Host receptors that can detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns and initiate signalling cascades, leading to an innate immune response. Examples include Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). PRRs can be membrane-bound receptors (as in the case of TLRs) or soluble cytoplasmic receptors (as in the case of NLRs, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5)).

- T-bet

A member of the T-box family of transcription factors. T-bet is a master switch in the development of T helper 1 (TH1) cell responses through its ability to regulate the expression of the interleukin-12 receptor, inhibit signals that promote TH2 cell development and promote the production of interferon-γ.

- Class switching

The process by which proliferating B cells rearrange their DNA to switch from expressing the heavy-chain constant region of IgM (or another class of immunoglobulin) to expressing that of a different immunoglobulin class, thereby producing antibodies with different effector functions. The decision of which isotype to generate is strongly influenced by the specific cytokine milieu and by other cells, such as T helper cells.

- Germinal centre

A highly specialized and dynamic microenvironment that gives rise to secondary B cell follicles during an immune response. Germinal centres are the main site of B cell maturation, which leads to the generation of memory B cells and plasma cells that produce high-affinity antibodies.

- Polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid

(PolyI:C). A substance that is used as a mimic of viral double-stranded RNA.

Biographies

Susan L. Swain is the former President and Director of the Trudeau Institute, Saranac Lake, New York, USA, and is now a professor of pathology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, USA. Her laboratory focuses on the generation and function of CD4+ memory T cells in infectious disease.

K. Kai McKinstry earned his Ph.D. in immunology from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada, and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Trudeau Institute. He is currently an instructor in the Department of Pathology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. His research is focused on how memory CD4+ T cells develop and how they contribute to protective secondary immune responses.

Tara M. Strutt has been an instructor in the Department of Pathology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School since 2010. She earned her Ph.D. in immunology from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Saskatchewan and did her postdoctoral work at the Trudeau Institute. Her primary research focus is the regulation of inflammation by memory CD4+ T cells.

Related links

FURTHER INFORMATION

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 1986;136:2348–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lund JM, Hsing L, Pham TT, Rudensky AY. Coordination of early protective immunity to viral infection by regulatory T cells. Science. 2008;320:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1155209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MA, Ravkov EV, Bevan MJ. Rapid culling of the CD4+ T cell repertoire in the transition from effector to memory. Immunity. 2008;28:533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinstry KK, Strutt TM, Swain SL. Regulation of CD4+ T-cell contraction during pathogen challenge. Immunol. Rev. 2010;236:110–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulendran B, Palucka K, Banchereau J. Sensing pathogens and tuning immune responses. Science. 2001;293:253–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1062060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constant SL, Bottomly K. Induction of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell responses: the alternative approaches. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulendran B. Modulating vaccine responses with dendritic cells and Toll-like receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2004;199:227–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousens LP, et al. Two roads diverged: interferon α/β- and interleukin 12-mediated pathways in promoting T cell interferon γ responses during viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1315–1328. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schijns VE, et al. Mice lacking IL-12 develop polarized Th1 cells during viral infection. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3958–3964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xing Z, Zganiacz A, Wang J, Divangahi M, Nawaz F. IL-12-independent Th1-type immune responses to respiratory viral infection: requirement of IL-18 for IFN-γ release in the lung but not for the differentiation of viral-reactive Th1-type lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2575–2584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxenius A, Karrer U, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. IL-12 is not required for induction of type 1 cytokine responses in viral infections. J. Immunol. 1999;162:965–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegazy AN, et al. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3+T-bet+ cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity. 2010;32:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YK, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity. 2009;30:92–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKinstry KK, et al. IL-10 deficiency unleashes an influenza-specific Th17 response and enhances survival against high-dose challenge. J. Immunol. 2009;182:7353–7363. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahon BP, et al. Poliovirus-specific CD4+ Th1 clones with both cytotoxic and helper activity mediate protective humoral immunity against a lethal poliovirus infection in transgenic mice expressing the human poliovirus receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1285–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maloy KJ, et al. CD4+ T cell subsets during virus infection. Protective capacity depends on effector cytokine secretion and on migratory capability. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:2159–2170. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coutelier JP, van der Logt JT, Heessen FW, Warnier G, Van Snick J. IgG2a restriction of murine antibodies elicited by viral infections. J. Exp. Med. 1987;165:64–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham MB, Braciale VL, Braciale TJ. Influenza virus-specific CD4+ T helper type 2 T lymphocytes do not promote recovery from experimental virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1273–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran TM, Isobe H, Fernandez-Sesma A, Schulman JL. Interleukin-4 causes delayed virus clearance in influenza virus-infected mice. J. Virol. 1996;70:5230–5235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5230-5235.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alwan WH, Kozlowska WJ, Openshaw PJ. Distinct types of lung disease caused by functional subsets of antiviral T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:81–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikemoto K, Pollard RB, Fukumoto T, Morimatsu M, Suzuki F. Small amounts of exogenous IL-4 increase the severity of encephalitis induced in mice by the intranasal infection of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1326–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsui M, Moriya O, Yoshimoto T, Akatsuka T. T-bet is required for protection against vaccinia virus infection. J. Virol. 2005;79:12798–12806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12798-12806.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arens R, et al. Cutting edge: murine cytomegalovirus induces a polyfunctional CD4 T cell response. J. Immunol. 2008;180:6472–6476. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suryawanshi A, et al. Role of IL-17 and Th17 cells in herpes simplex virus-induced corneal immunopathology. J. Immunol. 2011;187:1919–1930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oyoshi MK, et al. Vaccinia virus inoculation in sites of allergic skin inflammation elicits a vigorous cutaneous IL-17 response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14954–14959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904021106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou W, Kang HS, Kim BS. Th17 cells enhance viral persistence and inhibit T cell cytotoxicity in a model of chronic virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:313–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowe CR, et al. Critical role of IL-17RA in immunopathology of influenza infection. J. Immunol. 2009;183:5301–5310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tate MD, et al. Neutrophils ameliorate lung injury and the development of severe disease during influenza infection. J. Immunol. 2009;183:7441–7450. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nature Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1903–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity. 2009;30:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crotty S, Kersh EN, Cannons J, Schwartzberg PL, Ahmed R. SAP is required for generating long-term humoral immunity. Nature. 2003;421:282–287. doi: 10.1038/nature01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCausland MM, et al. SAP regulation of follicular helper CD4 T cell development and humoral immunity is independent of SLAM and Fyn kinase. J. Immunol. 2007;178:817–828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamperschroer C, Dibble JP, Meents DL, Schwartzberg PL, Swain SL. SAP is required for Th cell function and for immunity to influenza. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5317–5327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, et al. Cellular immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection in senescent BALB/c mice: CD4+ T cells are important in control of SARS-CoV infection. J. Virol. 2010;84:1289–1301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sette A, et al. Selective CD4+ T cell help for antibody responses to a large viral pathogen: deterministic linkage of specificities. Immunity. 2008;28:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu T, Chambers TJ. Yellow fever virus encephalitis: properties of the brain-associated T-cell response during virus clearance in normal and γ interferon-deficient mice and requirement for CD4+ lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2001;75:2107–2118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2107-2118.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomsen AR, et al. Cooperation of B cells and T cells is required for survival of mice infected with vesicular stomatitis virus. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:1757–1766. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu KT, et al. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borrow P, et al. CD40L-deficient mice show deficits in antiviral immunity and have an impaired memory CD8+ CTL response. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:2129–2142. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edelmann KH, Wilson CB. Role of CD28/CD80–86 and CD40/CD154 costimulatory interactions in host defense to primary herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 2001;75:612–621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.612-621.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sangster MY, et al. An early CD4+ T cell-dependent immunoglobulin A response to influenza infection in the absence of key cognate T–B interactions. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1011–1021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertram EM, et al. Role of ICOS versus CD28 in antiviral immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3376–3385. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3376::AID-IMMU3376>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kopf M, et al. OX40-deficient mice are defective in Th cell proliferation but are competent in generating B cell and CTL responses after virus infection. Immunity. 1999;11:699–708. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee BO, Hartson L, Randall TD. CD40-deficient, influenza-specific CD8 memory T cells develop and function normally in a CD40-sufficient environment. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1759–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson S, et al. Selected Toll-like receptor ligands and viruses promote helper-independent cytotoxic T cell priming by upregulating CD40L on dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;30:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300:337–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun JC, Bevan MJ. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science. 2003;300:339–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1083317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton-Williams EE, et al. Cutting edge: TLR ligands are not sufficient to break cross-tolerance to self-antigens. J. Immunol. 2005;174:1159–1163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novy P, Quigley M, Huang X, Yang Y. CD4 T cells are required for CD8 T cell survival during both primary and memory recall responses. J. Immunol. 2007;179:8243–8251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith CM, et al. Cognate CD4+ T cell licensing of dendritic cells in CD8+ T cell immunity. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/ni1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riberdy JM, Christensen JP, Branum K, Doherty PC. Diminished primary and secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in CD4-depleted Ig−/– mice. J. Virol. 2000;74:9762–9765. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.20.9762-9765.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tripp RA, Sarawar SR, Doherty PC. Characteristics of the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response in mice homozygous for disruption of the H-2lAb gene. J. Immunol. 1995;155:2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belz GT, Wodarz D, Diaz G, Nowak MA, Doherty PC. Compromised influenza virus-specific CD8+-T-cell memory in CD4+-T-cell-deficient mice. J. Virol. 2002;76:12388–12393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12388-12393.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiesel M, Kratky W, Oxenius A. Type I IFN substitutes for T cell help during viral infections. J. Immunol. 2011;186:754–763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Castellino F, et al. Chemokines enhance immunity by guiding naive CD8+ T cells to sites of CD4+ T cell–dendritic cell interaction. Nature. 2006;440:890–895. doi: 10.1038/nature04651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mueller SN, et al. CD4+ T cells can protect APC from CTL-mediated elimination. J. Immunol. 2006;176:7379–7384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Janssen EM, et al. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;421:852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Northrop JK, Thomas RM, Wells AD, Shen H. Epigenetic remodeling of the IL-2 and IFN-γ loci in memory CD8 T cells is influenced by CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1062–1069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janssen EM, et al. CD4+ T-cell help controls CD8+ T-cell memory via TRAIL-mediated activation-induced cell death. Nature. 2005;434:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature03337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Badovinac VP, Messingham KA, Griffith TS, Harty JT. TRAIL deficiency delays, but does not prevent, erosion in the quality of “helpless” memory CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:999–1006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sacks JA, Bevan MJ. TRAIL deficiency does not rescue impaired CD8+ T cell memory generated in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. J. Immunol. 2008;180:4570–4576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fuse S, et al. Recall responses by helpless memory CD8+ T cells are restricted by the up-regulation of PD-1. J. Immunol. 2009;182:4244–4254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Intlekofer AM, et al. Requirement for T-bet in the aberrant differentiation of unhelped memory CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2015–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oh S, et al. IL-15 as a mediator of CD4+ help for CD8+ T cell longevity and avoidance of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5201–5206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801003105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams MA, Tyznik AJ, Bevan MJ. Interleukin-2 signals during priming are required for secondary expansion of CD8+ memory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature04790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Obar JJ, et al. CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:193–198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909945107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barker BR, Gladstone MN, Gillard GO, Panas MW, Letvin NL. Critical role for IL-21 in both primary and memory anti-viral CD8+ T-cell responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:3085–3096. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bourgeois C, Rocha B, Tanchot C. A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science. 2002;297:2060–2063. doi: 10.1126/science.1072615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun JC, Williams MA, Bevan MJ. CD4+ T cells are required for the maintenance, not programming, of memory CD8+ T cells after acute infection. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:927–933. doi: 10.1038/ni1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Azadniv M, Bowers WJ, Topham DJ, Crispe IN. CD4+ T cell effects on CD8+ T cell location defined using bioluminescence. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roman E, et al. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:957–968. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kushnir N, et al. B2 but not B1 cells can contribute to CD4+ T-cell-mediated clearance of rotavirus in SCID mice. J. Virol. 2001;75:5482–5490. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5482-5490.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hou S, Doherty PC, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R, Katz JM. Delayed clearance of Sendai virus in mice lacking class I MHC-restricted CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 1992;149:1319–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hogan RJ, et al. Protection from respiratory virus infections can be mediated by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells that persist in the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:981–986. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sparks-Thissen RL, Braaten DC, Kreher S, Speck SH, Virgin HW. An optimized CD4 T-cell response can control productive and latent gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Virol. 2004;78:6827–6835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6827-6835.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stuller KA, Cush SS, Flano E. Persistent γ-herpesvirus infection induces a CD4 T cell response containing functionally distinct effector populations. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3850–3856. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brien JD, Uhrlaub JL, Nikolich-Zugich J. West Nile virus-specific CD4 T cells exhibit direct antiviral cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity and are sufficient for antiviral protection. J. Immunol. 2008;181:8568–8575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson AJ, Chu CF, Milligan GN. Effector CD4+ T-cell involvement in clearance of infectious herpes simplex virus type 1 from sensory ganglia and spinal cords. J. Virol. 2008;82:9678–9688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01159-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ishikawa T, et al. Protective role of Fas–FasL signaling in lethal infection with herpes simplex virus type 2 in mice. J. Virol. 2009;83:11777–11783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teijaro JR, Verhoeven D, Page CA, Turner D, Farber DL. Memory CD4 T cells direct protective responses to influenza virus in the lungs through helper-independent mechanisms. J. Virol. 2010;84:9217–9226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01069-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brown DM, Dilzer AM, Meents DL, Swain SL. CD4 T cell-mediated protection from lethal influenza: perforin and antibody-mediated mechanisms give a one-two punch. J. Immunol. 2006;177:2888–2898. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yauch LE, et al. CD4+ T cells are not required for the induction of dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cell or antibody responses but contribute to protection after vaccination. J. Immunol. 2010;185:5405–5416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brooke CB, Deming DJ, Whitmore AC, White LJ, Johnston RE. T cells facilitate recovery from Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus-induced encephalomyelitis in the absence of antibody. J. Virol. 2010;84:4556–4568. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02545-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Savarin C, Bergmann CC, Hinton DR, Ransohoff RM, Stohlman SA. Memory CD4+ T-cell-mediated protection from lethal coronavirus encephalomyelitis. J. Virol. 2008;82:12432–12440. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01267-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oxenius A, et al. CD40–CD40 ligand interactions are critical in T–B cooperation but not for other anti-viral CD4+ T cell functions. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:2209–2218. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pike R, et al. Race between retroviral spread and CD4+ T-cell response determines the outcome of acute Friend virus infection. J. Virol. 2009;83:11211–11222. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Iwashiro M, Peterson K, Messer RJ, Stromnes IM, Hasenkrug KJ. CD4+ T cells and γinterferon in the long-term control of persistent Friend retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 2001;75:52–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.52-60.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jellison ER, Kim SK, Welsh RM. Cutting edge: MHC class II-restricted killing in vivo during viral infection. J. Immunol. 2005;174:614–618. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown DM, Kamperschroer C, Dilzer AM, Roberts DM, Swain SL. IL-2 and antigen dose differentially regulate perforin- and FasL-mediated cytolytic activity in antigen specific CD4+ T cells. Cell. Immunol. 2009;257:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qui HZ, et al. CD134 plus CD137 dual costimulation induces Eomesodermin in CD4 T cells to program cytotoxic Th1 differentiation. J. Immunol. 2011;187:3555–3564. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Debbabi H, et al. Primary type II alveolar epithelial cells present microbial antigens to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:L274–L279. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]