Abstract

The bHLH-PAS transcription factor, CLOCK, is a key component of the molecular circadian clock within pacemaker neurons of the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Here we report that homozygous Clock mutant mice have a greatly attenuated diurnal feeding rhythm, are hyperphagic and obese, and develop a metabolic syndrome of hyperleptinemia, hyperlipidemia, hepatic steatosis and hyperglycemia, with insufficient compensatory insulin production, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, the levels of expression of hypothalamic peptides associated with energy balance were greatly attenuated in the Clock mutant animals. Taken together, these results indicate that the circadian clock gene network plays an important role in mammalian energy balance that involves a number of central and peripheral tissues, and disruption of this network can lead to obesity and the metabolic syndrome in mice.

Major components of energy homeostasis, including the sleep-wake cycle, thermogenesis, feeding, glucose and lipid metabolism, are subjected to circadian regulation that synchronizes energy intake and expenditure with changes in the external environment imposed by the rising and setting of the sun. The neural circadian clock located within the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) orchestrates 24 hr cycles in these behavioral and physiological rhythms [1–3]. However, the discovery that clock genes can regulate circadian rhythmicity in vitro in other central, as well as peripheral tissues, including those involved in nutrient homeostasis (e.g., mediobasal hypothalamus, liver, muscle, pancreas), indicates that circadian and metabolic processes are linked at the systems, cellular and molecular levels [4–8]. The recent finding that changes in the ratio of oxidized to reduced NAD(P) controls transcriptional activity of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein, NPAS2, a homologue of a primary circadian gene, Clock, suggests that cell redox may couple the expression of metabolic and circadian genes [9, 10]. The identification of the Clock mutant mouse which shows profound changes in circadian rhythmicity [11] offers an experimental genetic model to analyze the link between circadian gene networks, behavior and metabolism in vivo.

Positional cloning and transgenic rescue of normal circadian phenotype identified Clock as a member of the bHLH Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) transcription factor family [12, 13]. The most pronounced alteration in circadian phenotype in Clock mutant animals, compared to wild-type (WT) mice, is a 1-hour increase in the free-running rhythm of locomotor activity in heterozygous animals in constant darkness (DD) and a 3–4 hour increase (i.e. period = 27–28 hours in DD) in circadian period in homozygous animals, which is often followed by a total breakdown of circadian rhythmicity (i.e. arrythmicity) after a few weeks in DD. Here we report that mice homozygous for the Clock mutation show an attenuated diurnal rhythm of feeding behavior, as well as profound changes in body weight regulation and fuel metabolism, which leads to obesity and markers indicative of diabetes.

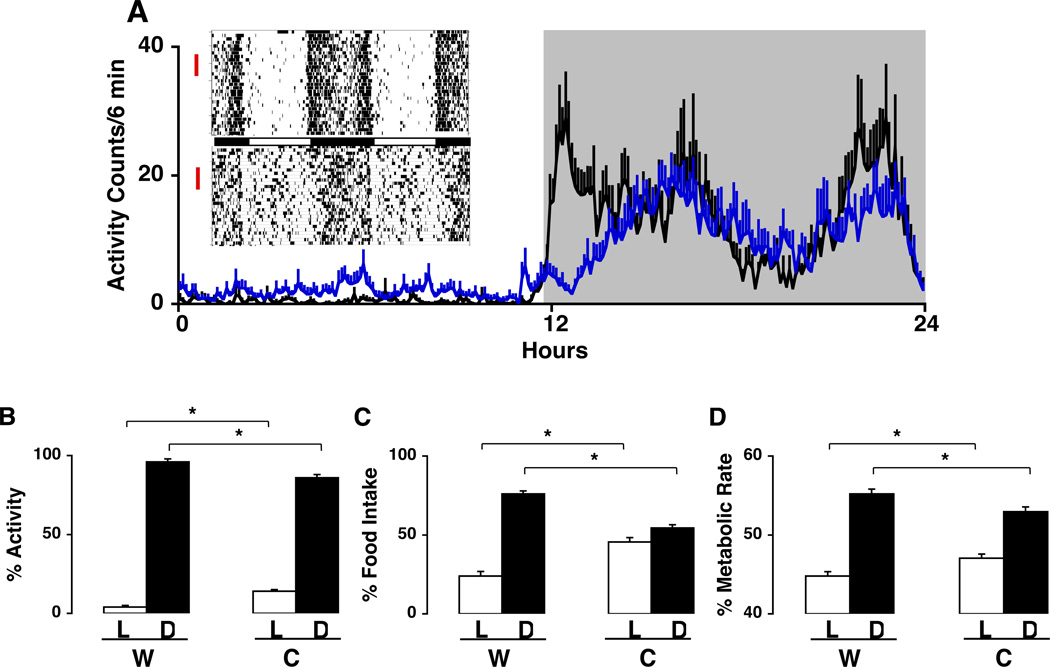

While previous studies using running wheel behavior as a marker of locomotor activity did not reveal major differences in Clock mutant and WT mice maintained on a light-dark (LD) cycle, use of infra-red beam crossing to monitor total activity revealed a significant increase in activity in the light phase, and a change in the temporal pattern of total activity in the dark phase (Fig. 1A). In particular, while WT animals showed two pronounced peaks of activity, one occurring after lights off, the other prior to lights on, these peaks were attenuated in Clock mutant animals. Surprisingly, despite there being a clear (but dampened) diurnal rhythm in locomotor activity in Clock mutant animals (Fig. 1B), the diurnal rhythm in food intake was severely altered in the Clock mutant animals (Fig. 1C), such that 53% of the food intake occurred during the dark in Clock mutant animals, while in WT mice 75% occurred during the dark. Similarly, the rhythm in energy expenditure, as measured by respiratory gas analysis, was also attenuated in the Clock mutant animal (Fig 1D). Overall there was a net (10%) decrease in energy expenditure in Clock mutant animals.

Fig. 1.

Altered diurnal rhythms in locomotor activity, feeding and metabolic rate in Clock mutant mice. (A) Insert on left: Actograms showing locomotor activity over a 30 day period in representative adult wild-type (WT) (top) and Clock mutant (bottom) mice individually housed in 12:12 LD (at 23°C) and provided food and water ad libitum. Activity bouts were analyzed using ClockLab software in 6-minute intervals across 7 days of recording (selected days are indicated by red vertical lines to the left of the actograms). Shown over the 24 hr cycle are activity counts during light (unshaded) and dark (shaded) periods (WT, n=5, black line; Clock, n=9, blue line). (B) Diurnal rhythm of locomotor activity for mice shown in (A). Activity counts were accumulated over the 12-hour light and 12-hour dark periods and expressed in each period as a percent of total 24-hour activity (*, p<0.05). Total activity over the 24-hour period was similar between genotypes. (C) Diurnal rhythm of food intake. Different groups of adult WT (N=7) and Clock mutant (N=5) mice were maintained on a regular diet (10% kcal/fat) and food intake (g) was measured during light and dark periods. Results shown are average food intake during light and dark periods as a percentage of total food intake (*, p<0.001).

(D) Diurnal rhythm of metabolic rate. Metabolic rate was determined in additional groups of WT (N=7) and Clock mutant (N=9) mice by indirect calorimetry under 12:12 LD conditions over a 3 day continuous monitoring period (*, p<0.05). Results shown are average metabolic rates during the light and dark periods as a percentage of total metabolic rate. Results shown (A–D) are expressed as group means ± SEM.

In addition to an alteration in the diurnal pattern of food intake, Clock mutant animals fed either a regular or a high fat diet showed a significant increase in energy intake and body weight compared to WT controls (Fig 2A, 2B). Fig. 2C shows the time course for the weight gain in Clock mutant and WT adult animals fed either a control or high fat diet for a period of 10 weeks beginning at 6 weeks of age. Comparison of somatic growth and solid organ mass did not reveal genotype-specific differences. Instead, the marked weight gain in Clock mutants fed a regular or high fat diet was specifically due to visceral adiposity (Fig. 2D, E) with about a 20–25% increase in lipid content on either diet.

Fig. 2.

Obesity in Clock mutant mice. (A) Energy intake. Average caloric intake over a 10 week period in male WT and Clock mutant mice. WT and Clock mutant mice were provided ad libitum access to regular (10% kcal/fat, WT, n=8, Clock, n=10) or high-fat chow (45% kcal/fat, WT, n=7, Clock, n=11) for 10 weeks beginning at 6 weeks of age. Weekly food intake was analyzed in the two groups (*, p<0.01). (B) Body weight. Body weights for the animals depicted in (A) after the 10 week study (*, p<0.01). (C) Longitudinal weight gain. Body weights WT (open) and Clock mutant (closed) mice over the 10 week study for animals depicted in (A) fed either regular (circle) or high fat (square) diets. (D) Post-weaning body weight of mice beginning at 10 days through 8 weeks of age. Growth curves in WT (open circle) and Clock mutant (closed circle) mice on regular chow were obtained by weighing animals weekly. Significant differences did not appear until 6 weeks of age (*, p<.05). All values (A–D) represent group means ± SEM

Because the Clock mutation could affect early fetal growth and development, we analyzed body weight in Clock and littermate pups throughout the first eight weeks of life. Body weights were similar in Clock mutant and wild-type animals during the first five weeks of life, but by 6 weeks of age Clock mutant animals were significantly heavier (Fig 2F), suggesting that the mutation did not effect fetal growth or nutrition. In a preliminary analysis, we found that the diurnal rhythm of food intake was already attenuated in 3 week old animals prior to any evidence of an increase in weight gain (See Supplemental Fig 1).

To determine if differences in weight and increases in adiposity in the Clock mutant mice were associated with changes in the regulation of fuel homeostasis, we sought to determine whether the Clock mutation altered the adipose-CNS axis that regulates feeding and energy expenditure. Histological analysis revealed adipocyte hypertrophy and lipid engorgement of hepatocytes with prominent glycogen accumulation (Fig. 3A) in Clock animals fed a high-fat diet; hallmarks of diet-induced obesity in WT animals. When measured at 6–7 months of age, Clock mutant animals also had hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglycerdemia, hyperglycemia and hypoinsulemia (Table 1). In addition, serum leptin levels increased during the light phase in Clock mutant animals fed a regular diet; this increase was accentuated in animals fed a high fat diet (Fig. 3B). These markers of metabolic dysregulation were not due to an increase in glucocorticoid production because levels of corticosterone were actually lower in the Clock mutant animals across the 24 hr LD cycle (WT = 5.5 ± 1.4 µg/dl Clock mutant = 2.6 ± 0.4, P< .05). Moreover, changes in blood lipid levels were correlated with tissue signs of lipid overload and glycogen accumulation in the liver, as well as with marked adipose hypertrophy compared to wild-type animals (Fig. 3A). Thus, the Clock mutant developed a spectrum of tissue and biochemical abnormalities that are hallmarks of metabolic disease.

Fig. 3.

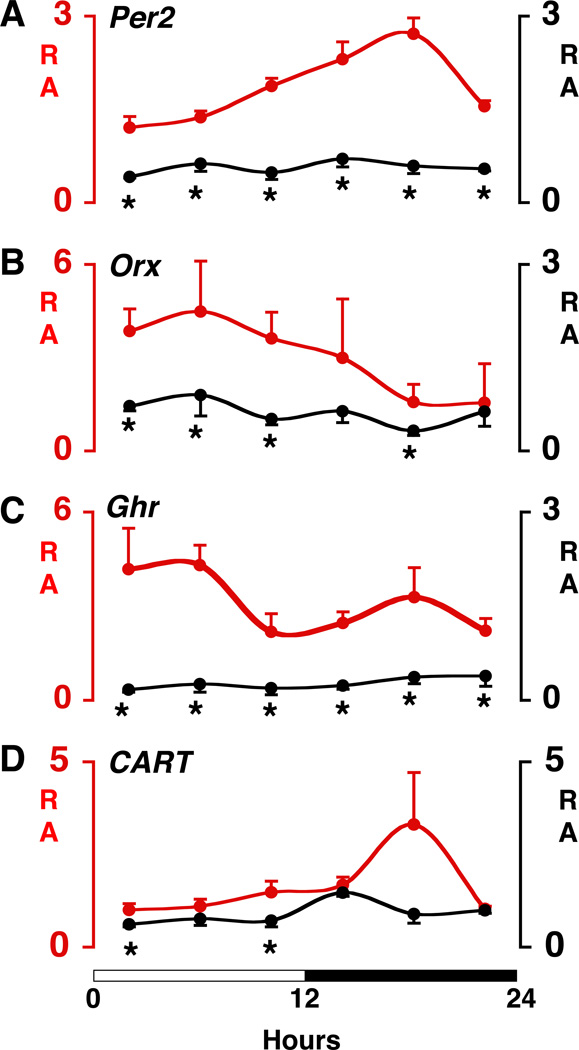

Altered diurnal rhythms and abundance in Clock mutant mice of Per2 mRNA and mRNAs encoding selected hypothalamic peptides involved in energy balance. (A–D) mRNA relative abundance (RA) curves. Time-course variation of transcripts in the hypothalamus of WT (red line) and Clock mutant (black line) mice across a 12:12 LD cycle (indicated by white-black bar on bottom). Real-time PCR was used to determine transcript levels. Values are displayed as RA (mean ± SEM) after normalization to glyseraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression levels in the same sample. Note that for visual clarity the RA scales vary for the different transcripts and vary between genotypes for orexin and ghrelin. Brains were collected at 4-hour intervals across the 12:12 LD cycle using four WT and four Clock mutant mice at each time point. Genotype comparisons were made at each 4-hour time point using independent sample t-tests with a significance level of p<.05 (*). Per2 = Period-2; Orx = Orexin; Ghr = Ghrelin; CART = Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript.

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters in WT and Clock mutant mice. Serum triglyceride, cholesterol, glucose, insulin and leptin concentrations were determined in 7–8 month old WT and Clock mutant mice fed a regular diet ad libitum (n=4–8 mice per group). For the measurement of glucose, insulin and leptin, blood was collected at 4-hour interval over a 24-hour time period via an indwelling catheter (40 µl per blood sample), and the data were pooled to provide an overall mean (± SEM) value. For triglyceride and cholesterol measurement, a single blood sample (160 µl) was collected at ZT 0.

| Metabolic parameters | WT | Clock | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 136 ± 8 | 164 ± 8 | P < 0.05 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 141 ± 9 | 163 ± 6 | P < 0.05 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 130 ± 5 | 161 ± 7 | P < 0.01 |

| Insulin (ng/ml) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | N.S. |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | P < 0.05 |

To test the hypothesis that obesity and metabolic dysregulation in the Clock mutant animals are associated with altered expression of neuropeptides involved in appetite regulation and energy balance, we analyzed transcript levels of known orexigenic and anorexigenic neuropeptides in the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) at 4-hr intervals across the light-dark cycle in wild-type and Clock homozygous mutant mice. For this analysis, we focused on the orexin transcript, because the orexinergic system is involved in both feeding and sleep-wake regulation [14, 15]. We also focused on ghrelin and CART, since these transcripts contain CLOCK responsive E-box elements [16, 17]. In addition, we examined the expression of a second circadian clock gene, Per2, a gene known to have a diurnal rhythm of expression in the retrochiasmatic area. The expression levels of Per2, orexin and ghrelin were dramatically reduced in Clock mutant mice at virtually all time points of the 12L:12D cycle (Figure 4). A small, but significant decrease in the expression level of CART in Clock mutant mice occurred during the beginning and end of the 12-hr light phase (Figure 4).

The present findings demonstrate that Clock mutant animals develop obesity, hyperphagia, reduced energy expenditure, adiposity, as well as dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. The results also reveal significant changes in the expression of mRNAs encoding the major neuropeptides that regulate feeding and energy expenditure within the hypothalamus. These broad effects of the Clock gene mutation on nutrient regulation reveal an unforeseen role for the circadian clock system in regulating more than just the timing of food intake and metabolic processes. The breadth of effects on metabolism at many different levels of organization makes the Clock mutant animal a unique model to extend analysis of behavior and fuel homeostasis from the complex neural system level down to cell and molecular levels in both central and peripheral tissues.

It should be noted that the effect of the Clock mutation on body weight in animals fed a regular diet was similar in magnitude to the effect of a high fat diet in wild-type animals (Fig 2). In addition, when Clock mutant animals were fed a high fat diet, the combined effect of the diet plus mutation led to the most severe alteration in body weight and markers of metabolism (Fig 2). Thus, a dysfunctional circadian system may be a risk factor equivalent to poor diet in causing weight gain and obesity.

Alterations in fuel metabolism in animals carrying a mutant circadian Clock gene could emerge from a cascade of neural events initiated by an alteration in circadian rhythms under the direct control of the SCN [18, 19], in particular the feeding rhythm, that is greatly attenuated in Clock mutant animals. Thus, the misalignment of food intake, and/or the near loss of feeding rhythmicity, could create metabolic instabilities that lead to hyperphagia and associated obesity and lipid/glucose irregularities. On the other hand, since circadian clock genes are also expressed in nearly all CNS and peripheral tissues, alterations in metabolism could be due to cell autonomous effects associated with altered expression of Clock in CNS feeding centers and/or peripheral tissues involved in metabolism [5, 20]. The observation that mRNAs of some of the major energy regulatory peptides are altered in both diurnality and absolute expression levels in the MBH supports a molecular coupling between circadian and metabolic transcription networks. These results are consistent with the recent finding that in addition to regulating the timing of many circadian clock controlled (CCG) genes, the circadian cellular oscillator regulates approximately 3–10% of transcripts expressed in any tissue [21–24].

Clues to the effects of the Clock mutation on energy balance may be indicated from the emerging map of SCN projections to critical energy centers within the hypothalamus. For example, SCN projections synapse directly upon lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) neurons that express orexins [25, 26], as well as indirectly via the subparaventricular nuclei (SPV). Additional evidence suggests that connections between the SCN and neurons within the MBH may have important effects on cell and molecular functions. Specifically, recent analyses from several groups have indicated that the growth hormone agonist, ghrelin, originally discovered as an incretin hormone within the stomach, may also be produced within the MBH/SPV [27–30]. Our real time PCR results provide further support for expression of ghrelin within the MBH. Remarkably, we find that ghrelin mRNA is greatly reduced in the MBH from Clock mutant animals, suggesting that signaling from SCN neurons and/or expression of the Clock gene within the MBH, may play a critical role in transcriptional control of target genes within the MBH. Similarly, we found that orexin levels were lower in Clock mutant than wild-type animals, and the normal diurnal variation in expression was abolished. Together, these observations raise the possibility that expression of the Clock gene may direct a transcriptional network involving either a direct or indirect activation of E box elements within target genes; both CART and ghrelin, which are diminished in the Clock mutant, contain E box elements that function in transcriptional regulation [16, 17, 31–33].

In addition to changes induced by the Clock mutation within the SCN and/or the MBH, cell autonomous function of the Clock gene in peripheral cells may indirectly cause a cascade of deficits that lead to hyperphagia and metabolic dysregulation. For example, the changes in glycogen accumulation and insulin in Clock mutant mice, may lead to altered glycemic control and nutrient sensing, and thereby create a perceived state of energy deficiency. This hypothesis is particularly intriguing in view of the fact that many tissues involved in fuel metabolism have recently been shown to possess a circadian clock core machinery and can produce circadian oscillations in vitro [4, 5, 8]. Indeed, we have recently found that the Islets of Langerhans express the Per2 gene and sustain circadian oscillations when maintained ex vivo (unpublished data FWT, JST, and JB). Thus, a mutation in a circadian clock gene would not only be altering molecular rhythms in SCN cells, and associated SCN-controlled behavioral and physiological rhythms, but also in all of the cells in which clock genes are expressed including liver, pancreas, fat and muscle. It will now be of great interest to discern downstream targets of the Clock gene within individual cells, and the interplay between peripheral and central actions of the Clock gene on whole animal physiology.

It is important to note that recent genome-wide expression profiling shows that nearly 10% of the mammalian genome varies as a function of circadian time, and that the expression levels of both clock controlled genes and non-rhythmic genes are altered in Clock mutant animals [21–24]. Importantly, previous transcriptome analysis in the SCN and liver of Clock mutant mice has uncovered global changes in metabolic pathways, including those encoding enzymes of glycolysis, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and lipid metabolism [21]. Input of the Clock gene into metabolic pathways may occur either directly through binding to E-box motifs or through tissue-specific transcription factors. Interestingly, both the core circadian machinery, and many of the same genes that are expressed according to a circadian pattern in the liver, are similarly expressed in other peripheral tissues including heart and muscle [8, 23], as well as in adipose and pancreatic tissue (unpublished results). Thus, at the local peripheral level, a change in the circadian core molecular machinery can be expected to alter the expression of clock controlled genes whose dysregulation at the local level could contribute to hepatic steatosis and hallmarks of the metabolic syndrome, through a bottom up cascade of events. The connection between metabolism and circadian rhythmicity is particularly intriguing in view of the recent finding that genes involved in mitochondrial redox metabolism account for a large fraction of the circadian transcriptome in the brain, liver and most tissues [9]. Thus, while these earlier results indicated that cell redox flux can alter the molecular circadian core machinery, our results in Clock mutant animals indicate that alterations in this molecular clock may alter cell metabolism, as well.

We previously demonstrated that Clock mutant mice have alterations in the amount of sleep they produce each day (1–2 hours less than wild-type controls). Recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated a close association between sleep time and obesity. Both human and animal studies have shown that experimental chronic sleep restriction or sleep deprivation lead to notable changes in energy balance and in hormone levels known to regulate adiposity and satiety [34–37]. The Clock mutant mouse represents an intriguing genetic animal model in which chronic sleep reduction, circadian dysregulation and obesity (and other metabolic changes) are associated with a single mutation, and represents a novel genetic model to investigate the complex neural and molecular mechanisms linking circadian rhythms, sleep and energy metabolism.

In just the past few years, two major developments have transformed our understanding of the circadian clock system in mammals: 1) the elucidation of the transcriptional-translational feedback loop(s) that drives cellular rhythms [2, 21], and 2) the discovery that circadian clocks are expressed in nearly all mammalian cells where they coordinate the cell cycle, growth, and metabolism [38]. These two observations have provided great insight into the challenges that organisms face to adapt their life style on the behavioral level to the 24-hr external world with its associated physical (e.g. light-dark) and biotic (e.g. predator-prey relationships) diurnal rhythms, and to coordinate events within the organism to maintain internal 24-hr temporal organization. The circadian clock is central for maintaining this temporal order, and the finding that a mutation of a canonical clock gene, Clock, leads to wide ranging alterations in fuel metabolism as well as metabolic characteristics associated with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome, emphasizes how critical normal diurnal timekeeping is, from molecular to behavioral levels, for the health and well being of the organism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health AG-18200, DK02675, AG11412, HL075029, and HL59598). J.S. Takahashi is an Investigator and E. McDearmon is an Associate in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Van Cauter E, Turek FW. Roles of sleep-wake and dark-light cycles in the control of endocrine, metabolic, cardiovascular and cognitive function, Volume IV: Coping With the Environment: Neural and Endocrine Mechanisms. In: McEwen BS, editor. Handbook of Physiology, Section 7: The Endocrine System. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418(6901):935–941. doi: 10.1038/nature00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi JS, Turek FW, Moore RY. Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology. In: NT A, editor. Circadian Clocks. Vol. 12. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. p. 770. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsalobre A, Damiola F, Schibler U. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell. 1998;93:929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stokkan KA, Yamazaki S, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science. 2001;291(5503):490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagita K, Tamanini F, van Der Horst GT, Okamura H. Molecular mechanisms of the biological clock in cultured fibroblasts. Science. 2001;292(5515):278–281. doi: 10.1126/science.1059542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe M, Herzog ED, Yamazaki S, Straume M, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Block GD. Circadian rhythms in isolated brain regions. J Neurosci. 2002;22(1):350–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00350.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(15):5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutter J, Reick M, Wu LC, McKnight SL. Regulation of clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors. Science. 2001;293(5529):510–514. doi: 10.1126/science.1060698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutter J, Reick M, McKnight SL. Metabolism and the control of circadian rhythms. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:307–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.142857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang A-M, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, Dove WF, Pinto LH, Turek FW, Takahashi JS. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch MP, Steeves TDL, Vitaterna MH, Kornhauser JM, Lowery PL, Turek FW, Takahashi JS. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian Clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoch MP, Song E, Chang A, Vitaterna MH, Zhao Y, Wilsbacher LD, Sangoram AM, King DP, Pinto LH, Takahashi JS. Functional identification of the mouse circadian Clock gene by transgenic BAC rescue. Cell. 1997;89:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Yanagisawa M. To eat or to sleep? Orexin in the regulation of feeding and wakefulness. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:429–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taheri S, Zeitzer JM, Mignot E. The role of hypocretins (orexins) in sleep regulation and narcolepsy. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:283–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada K, Yuan X, Otabe S, Koyanagi A, Koyama W, Makita Z. Sequencing of the putative promoter region of the cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated-transcript gene and identification of polymorphic sites associated with obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(1):132–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanamoto N, Akamizu T, Tagami T, Hataya Y, Moriyama K, Takaya K, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Nakao K. Genomic structure and characterization of the 5'-flanking region of the human ghrelin gene. Endocrinology. 2004;145(9):4144–4153. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalsbeek A, Fliers E, Romijn JA, La Fleur SE, Wortel J, Bakker O, Endert E, Buijs RM. The suprachiasmatic nucleus generates the diurnal changes in plasma leptin levels. Endocrinology. 2001;142(6):2677–2685. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.la Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A, Wortel J, Fekkes ML, Buijs RM. A daily rhythm in glucose tolerance: a role for the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Diabetes. 2001;50(6):1237–1243. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura Y, Accili D. New insights into the integrated physiology of insulin action. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2004;5(2):143–149. doi: 10.1023/B:REMD.0000021436.91347.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109(3):307–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhtar RA, Reddy AB, Maywood ES, Clayton JD, King VM, Smith AG, Gant TW, Hastings MH, Kyriacou CP. Circadian cycling of the mouse liver transcriptome, as revealed by cDNA microarray, is driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Curr Biol. 2002;12(7):540–550. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Storch KF, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH, Weitz CJ. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002;417(6884):78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda HR, Chen W, Adachi A, Wakamatsu H, Hayashi S, Takasugi T, Nagano M, Nakahama K, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Iino M, Shigeyoshi Y, Hashimoto S. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature. 2002;418(6897):534–539. doi: 10.1038/nature00906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saper CB, Chou TC, Elmquist JK. The need to feed: homeostatic and hedonic control of eating. Neuron. 2002;36(2):199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath TL, Diano S. The floating blueprint of hypothalamic feeding circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(8):662–667. doi: 10.1038/nrn1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inui A. Ghrelin: an orexigenic and somatotrophic signal from the stomach. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(8):551–560. doi: 10.1038/35086018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowley MA, Smith RG, Diano S, Tschop M, Pronchuk N, Grove KL, Strasburger CJ, Bidlingmaier M, Esterman M, Heiman ML, Garcia-Segura LM, Nillni EA, Mendez P, Low MJ, Sotonyi P, Friedman JM, Liu H, Pinto S, Colmers WF, Cone RD, Horvath TL. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron. 2003;37(4):649–661. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvath TL, Diano S, Sotonyi P, Heiman M, Tschop M. Minireview: ghrelin and the regulation of energy balance--a hypothalamic perspective. Endocrinology. 2001;142(10):4163–4169. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodosi B, Gardi J, Hajdu I, Szentirmai E, Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Rhythms of ghrelin, leptin, and sleep in rats: effects of the normal diurnal cycle, restricted feeding, and sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(5):R1071–R1079. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00294.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishimoto M, Okimura Y, Nakata H, Kudo T, Iguchi G, Takahashi Y, Kaji H, Chihara K. Cloning and characterization of the 5(')-flanking region of the human ghrelin gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305(1):186–192. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominguez G, Lakatos A, Kuhar MJ. Characterization of the cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) peptide gene promoter and its activation by a cyclic AMP-dependent signaling pathway in GH3 cells. J Neurochem. 2002;80(5):885–893. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munoz E, Brewer M, Baler R. Circadian Transcription. Thinking outside the E-Box. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):36009–36017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Everson CA, Crowley WR. Reductions in circulating anabolic hormones induced by sustained sleep deprivation in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(6):E1060–E1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00553.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel K, Leproult R, L'Hermite-Baleriaux M, Copinschi G, Penev PD, Van Cauter E. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(11):5762–5771. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):846–850. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short Sleep Duration is Associated with Reduced Leptin, Elevated Ghrelin, and Increased Body Mass Index. PLoS Medicine. 2004;1(3):62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schibler U, Sassone-Corsi P. A web of circadian pacemakers. Cell. 2002;111(7):919–922. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.