Abstract

We report the early conformation of the E. coli signal recognition particle (SRP) and its receptor FtsY bound to the translating ribosome by cryo-electron microscopy. FtsY binds to the tetraloop of the SRP RNA whereas the NG-domains of the SRP protein and FtsY interact weakly in this conformation. Our results suggest that optimal positioning of the SRP RNA tetraloop and the Ffh NG-domain leads to FtsY recruitment.

In all organisms, the SRP targets nascent polypeptides with a signal sequence to the translocation machinery in the membrane through association with its membrane-localized receptor1–4. In E. coli, SRP consists of one protein (Ffh) and a 4.5S RNA (114 nucleotides). Ffh and FtsY each contain a conserved NG-domain with a GTPase G-domain and a N-domain5,6. Assembly between the SRP and FtsY NG-domains mediates delivery of ribosome-nascent chain complexes (RNCs) to the membrane, and subsequent reciprocal GTPase activation coordinates the transfer of the signal sequence to the translocon7. In the co-crystal structure of the Thermus aquaticus Ffh-FtsY NG-domains, the G-domains form a composite active site8,9 suggesting a mechanism for GTPase activation. The conserved Ffh M-domain recognizes the signal sequence and binds the 4.5S RNA10. E. coli FtsY contains an additional, weakly-conserved A-domain implicated in membrane interaction and translocon association11.

Three conformations of the SRP-FtsY complex are identified in coordinating the transfer of the RNC to the translocon12. First, a GTP-independent early Ffh-FtsY complex is formed which subsequently rearranges to the GTP-dependent closed conformation bringing the G-domains in close contact. The activated state requires alignment of conserved residues with respect to both GTP molecules in the GTPase active site. The RNC accelerates assembly of a stable SRP-FtsY complex but thermodynamically disfavors the rearrangement into the closed state, primarily through preferential stabilization of the early conformation12. Here, we describe the cryo-EM structure of the E. coli ribosome-SRP-FtsY complex in the early conformation, demonstrating that the ribosome acts as a platform that optimally positions critical SRP regions for receptor recruitment.

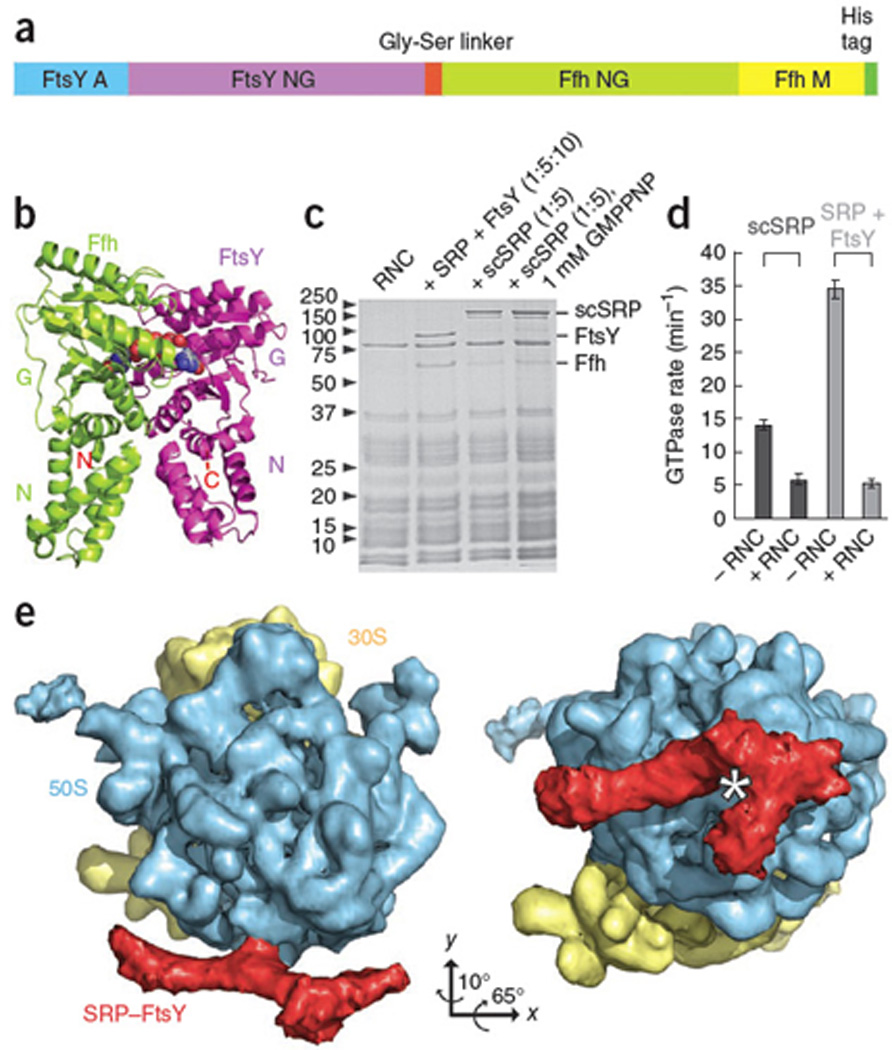

SRP and FtsY form a complex with ribosomes displaying an FtsQ signal sequence13 (Fig.1). However, this complex is not stable enough to be visualized by cryo-EM. To stabilize the Ffh-FtsY interaction, the FtsY C-terminus was fused to the Ffh N-terminus via a 31-residue glycine-serine linker yielding a single-chain construct (scSRP) (Fig.1a,b; Supplementary Methods). This scSRP binds ribosomes as efficiently as unlinked SRP and FtsY (Fig.1c). Importantly, GTPase activity is preserved in scSRP, and likewise suppressed by the RNC12 (Fig.1d, Supplementary Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Generation and Characterization of RNC-SRP-FtsY. (a) Schematic of the single-chain SRP-FtsY construct (scSRP). (b) Co-crystal structure of the Ffh (green)-FtsY (magenta) NG-domain complex8,9. (c) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing binding of the SRP (Ffh), FtsY and scSRP to RNC analyzed by ribosomal pelleting. scSRP binds in presence and absence of non-hydrolysable GTP (GMPPNP). (d) GTPase activity of the scSRP construct (dark grey) is within two-fold of unlinked SRP and FtsY (light grey) and inhibited by RNCs. Standard deviation from three different experiments is indicated by error bars. (e) Cryo-EM structure of RNC-scSRP. 30S: yellow, 50S: blue, scSRP: red, star: tunnel exit. All figures were produced with the programs Adobe Illustrator and PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

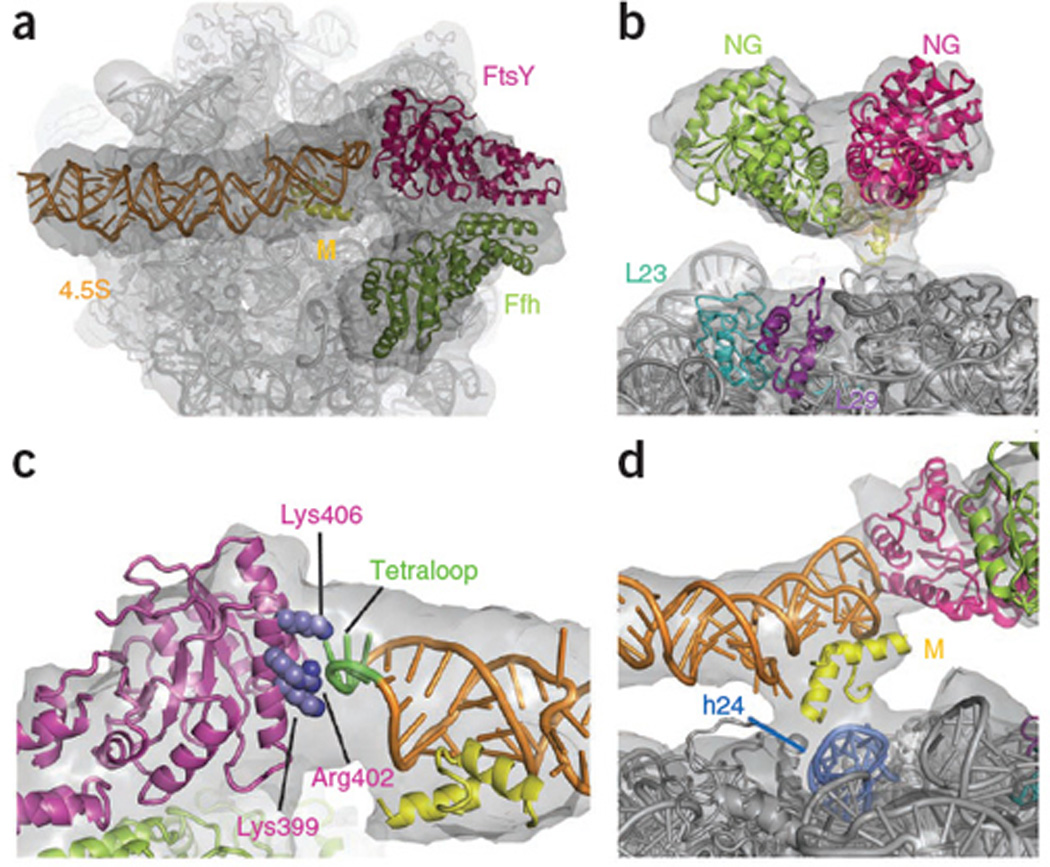

To stall the early conformation the cryo-EM sample contained a 15-fold excess of scSRP over RNCs without nucleotides. After multi-particle refinement, the RNC-scSRP structure was reconstructed at 13Å resolution (FSC0.5 criterion) (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figs.2, 3). At the exit of the ribosomal tunnel, large extra density is observed resembling the previously determined RNC-SRP complex13,14 (197Å×97Å) (Fig.1e). The atomic model of RNC-scSRP was generated by fitting crystal structures of the E. coli 70S ribosome15, the E. coli 4.5S RNA-M-domain10, and the individual T. aquaticus Ffh and FtsY NG-domains8 into the experimental density (Fig.2, Supplementary Methods). The bilobal density at the tunnel exit can be attributed to the highly homologous NG-domains of Ffh and FtsY with two possible orientations. Fitting Ffh and FtsY NG-domains as shown in Fig.2 is (i) more consistent with the position of the linker between the Ffh NG- and M-domain, (ii) requires least Ffh rearrangements compared to the SRP-RNC complex (Supplementary Fig.4) and (iii) agrees with the biochemical data (Supplementary Discussion). Although our scSRP construct comprises the complete FtsY A-domain, this domain is not visible in our structure and thus likely to be disordered in the targeting complex.

Figure 2.

Atomic Model of the Early Conformation of scSRP. (a) View on the tunnel exit. (b) The Ffh-FtsY NG-domains have a loose interface and do not contact L23,L29. (c) FtsY G-domain contacts the RNA tetraloop (green) via Lys399, Arg402 and Lys406 (blue). View from the tunnel exit. The side-chain placement is based on the Ffh-FtsY NG-domain complex structure8. (d) Ribosomal connection formed by the M-domain helices2,3 and rRNA helix24 (marine). Experimental density: grey; 4.5S RNA: orange; Ffh M-domain (helices2,3): yellow; Ffh NG-domain: limon; FtsY: magenta; rRNA: grey.

The loosely packed Ffh-FtsY NG-domain interface (Fig.2b) does not involve the G-domains in our model of the nucleotide-independent, early conformation. Consistently, the GTPase active sites are accessible in the early conformation for GTP binding and exchange. However, in the closed and activated states the G domains form a composite GTPase site8,9. This conformational change is consistent with fluorescence-resonance-energy-transfer (FRET) measurements using fluorescent labels attached to Ffh153 and FtsY345. These showed low FRET signal in the early state, which increased considerably upon addition of non-hydrolysable GTP (GMPPNP)12 (Supplementary Fig.5).

Based on the fitting of the NG-domains, the FtsY G-domain contacts the conserved 4.5S RNA tetraloop via a positively charged α-helix (Fig.2c). Mutations in Lys399, Arg402 and Lys406 were shown to interfere with the ability of the RNA tetraloop to catalyze complex formation similar to tetraloop mutations16–18. This underscores the critical role of the FtsY-RNA tetraloop interaction in stabilizing the early conformation. In contrast, in a cryo-EM structure of the eukaryotic RNC-SRP-SR complex obtained in GMPPNP, which presumably represents the closed or activated conformation, the homologous NG-domains of SRP and SRα dissociated from the tetraloop of the SRP RNA and were not visible19. This suggests that subsequent closing of the complex and GTPase activation leads to the dissociation of the NG-domains from the SRP RNA tetraloop.

We observe only a single ribosomal contact (Fig.2d), in contrast to four contacts in the RNC-SRP structures13,14. The contact between the Ffh N-domain and ribosomal proteins L23,L29 is lost in this complex (Fig.2b) but the GTPases remain close to the exit site. The density at the connection is also weak (Fig.2d), suggesting that a portion of the M-domain and the signal sequence becomes flexible13,14. Thus, this structure may represent the first of a series of FtsY-induced rearrangements leading to the detachment of the SRP from the ribosome. This detachment could allow for initial contact between the translocon and L23, which is the major translocon-contact site, thus fostering successful transfer of the RNC from the SRP to the translocon.

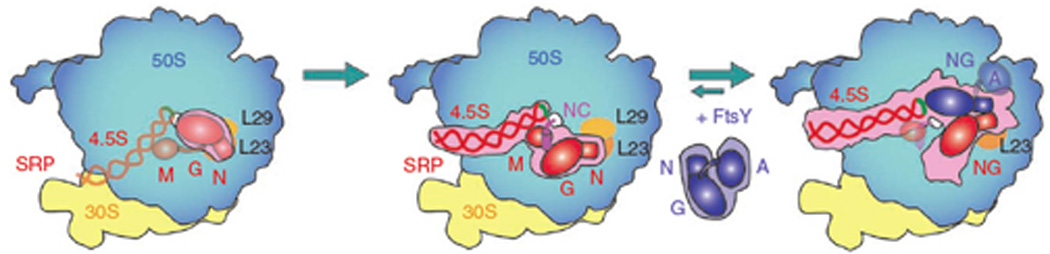

FtsY interacts simultaneously with the SRP RNA tetraloop and the Ffh protein. Notably, the RNA tetraloop is not positioned to contact FtsY in any crystal structures of free SRP, suggesting that the RNC serves as a platform to conformationally preorganize SRP for receptor-binding (Fig.3). Therefore, the sequence of events can be summarized as follows: (i) initial interaction of the Ffh N-domain and L2313, (ii) recognition of the signal sequence causing SRP to dock onto the RNC13,14, (iii) receptor binding stabilized by interactions of the RNA tetraloop with FtsY leading to the early RNC-SRP-FtsY complex presented here. These structural observations are supported by biochemical evidence indicating that, compared to free SRP, RNC-bound SRP forms a 50-fold more stable early complex with FtsY and that the RNA tetraloop and the basic residues on the lateral surface of FtsY are important for this initial receptor recruitment12,16. This functional model reinforces the key role of SRP RNA20 in transmitting information regarding the presence of a signal sequence bound to the Ffh M-domain to the Ffh-FtsY GTPases.

Figure 3.

Cartoon Model of Co-translational Targeting. The Ffh N-domain binds L23 (left). Upon recognition of a signal sequence, the SRP binds with high affinity to the RNC (middle), and is prepositioned to bind FtsY. In the early conformation (right), the FtsY NG-domain contacts the 4.5S RNA tetraloop initiating the rearrangement of the GTPase domains and release of the RNC. The colored outlines are based on EM reconstructions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Guy Schoehn for collecting EM data, Imre Berger for designing scSRP, Christian Frick for technical assistance and Xin Zhang for helpful suggestions. Wolfgang Wintermeyer (Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Goettingen, Germany) kindly provided pET24a-Ffh. Joen Luirink (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) is acknowledged for providing pET9-FtsY. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the National Center of Excellence in Research Structural Biology program of the SNSF. The authors acknowledge support by the Electron Microscopy of ETH Zurich (EMEZ) and from the infrastructure of the Partnership for Structural Biology in Grenoble.

Footnotes

ACCESSION CODES

Protein Data Bank: The atomic model of SRP-FtsY in the early conformation has been deposited with accession code 2xkv. The cryo-EM map has been deposited in the 3D-EM database under accession number EMD-1762.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.S. conceived the scSRP construct and performed sample preparations; S.-o.S. performed activity assays; D.B. did the electron microscopy; D.B., L.E. and C.S. performed the image analysis and model building; C.S., N.B., D.B. and S.-o.S prepared the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walter P, Johnson AE. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1994;10:87–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagai K, et al. EMBO J. 2003;22:3479–3485. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doudna JA, Batey RT. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:539–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulbrandt ND, Newitt JA, Bernstein HD. Cell. 1997;88:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freymann DM, Keenan RJ, Stroud RM, Walter P. Nature. 1997;385:361–364. doi: 10.1038/385361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montoya G, Svensson C, Luirink J, Sinning I. Nature. 1997;385:365–368. doi: 10.1038/385365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly T, Rapiejko P, Gilmore R. Science. 1991;252:1171–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Focia PJ, Shepotinovskaya IV, Seidler JA, Freymann DM. Science. 2004;303:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1090827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egea PF, et al. Nature. 2004;427:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature02250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batey RT, et al. Science. 2000;287:1232–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiche B, et al. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Schaffitzel C, Ban N, Shan SO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1754–1759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808573106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaffitzel C, et al. Nature. 2006;444:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nature05182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halic M, et al. Nature. 2006;444:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature05326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuwirth BS, et al. Science. 2005;310:827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1117230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen K, Shan SO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7698–7703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002968107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagath JR, et al. RNA. 2001;7:293–301. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siu FY, Spanggord RJ, Doudna JA. RNA. 2007;13:240–250. doi: 10.1261/rna.135407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halic M, et al. Science. 2006;312:745–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1124864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw N, Neher SB, Booth DS, Walter P. Science. 2009;323:127–130. doi: 10.1126/science.1165971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.