Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has gained popularity and acceptance among bariatric surgeons, mainly due its low morbidity and mortality. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery has emerged as another modality of carrying out the bariatric procedures. While the single-incision transumbilical (SITU) approach represents an advance, especially for cosmetic reasons, its application in morbid obesity at present is limited. We describe our short-term surgical results and technical considerations with SITU-SG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

SITU-SG was performed in 10 patients between June 2010 and June 2011. SG was performed in a standard fashion and was started 6 cm from the pylorus using a 36 French bougie.

RESULTS:

They were all females with a mean age of 45 years. Preoperative BMI was 40 kg/m2 (range, 35–45). The mean operative time was 98 min. No peri- or postoperative complications or deaths occurred. All patients were very satisfied with the cosmetic outcomes and excess weight loss.

CONCLUSION:

True SITU laparoscopic SG is safe and feasible and can be performed without changing the existing principles of the procedure.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, single-incision laparoscopic surgery, single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic surgery, sleeve gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has become a major health problem in the industrialized countries worldwide. Only bariatric surgery being the therapeutic modality offering substantial weight loss and significant improvements of comorbidities, bariatric surgery has quickly become one of the fastest growing fields of medicine. The demands for less-invasive bariatric procedures are gaining more popularity and, as a result, bariatric procedures have become no exception to the ever-advancing quest of minimally invasive surgery. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is an emerging new bariatric procedure. Recent studies suggest that a second-stage surgical procedure is not always warranted if adequate weight loss and comorbidity resolution are achieved, and the procedure could be a safe and effective stand-alone procedure for the treatment of morbid obesity. The benefits of SG include a low rate of complications, maintenance of gastrointestinal continuity, and absence of malabsorption.[1,2,3] Currently single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) is considered to be a bridging technique to natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Applications of SILS have expanded rapidly, and various procedures including bariatric surgery have been carried out with this technique.[4,5,6,7,8,9] The single-incision transumbilical (SITU) approach represents an advance, especially for cosmetic reasons. We describe our short-term surgical results and technical considerations with true transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SITU-SG).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included the first 10 consecutive female morbidly obese patients who underwent SITU-SG as a primary and potentially definitive bariatric procedure between June 2010 and June 2011. The mean preoperative BMI was 40.4 kg/m2 (range, 35.1-44.9).

All patients were required to have psychological screening, routine labs, electrocardiogram, gastroscopy, esophageal manometry, 24-h pH monitoring, pulmonary function studies, and a medical evaluation. All patients entering our practice requesting bariatric surgery were offered four procedure options: adjustable gastric banding, laparoscopic gastric bypass, laparoscopic SG and SITU-SG. None of the patients had undergone previous bariatric surgery.

Exclusion criteria were heavy sweat-eaters, BMI greater than 50, tall patients (height > 180 cm), patients with prior upper abdominal surgery or prior umbilical hernia repair with mesh, patients with hiatal hernia or with functional disorders of the lower esophageal sphincter, patients with psychiatric disorders and addiction to either drugs or alcohol, and patients with high operative risk.

All patients were considered as candidates provided that they did not have the above-mentioned exclusion criteria. All patients were preoperatively evaluated by a dietician and also by relative specialties based on the individual needs. The final decision for surgery was made both by the surgeon and the patient after a detailed discussion. All the patients were well informed of the possible options along with the risks and the benefits of all the bariatric procedures suitable for them. All patients were scheduled for SITU-SG as a primary definitive procedure. Our patients were not investigated for gall stones neither by USG nor CT scan routinely. We only investigate patients for gall stones if they are symptomatic, e.g. biliary colic. Preoperatively our patients received no liquid diet to shrink livers. All patients received intravenous antibiotics, subcutaneous unfractionated heparin and sequential compression devices preoperatively. Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis comprised daily injections of low molecular weight heparin (starting 12 h prior surgery) and administration of DVT stockings for the hospital stay.

Surgical Technique

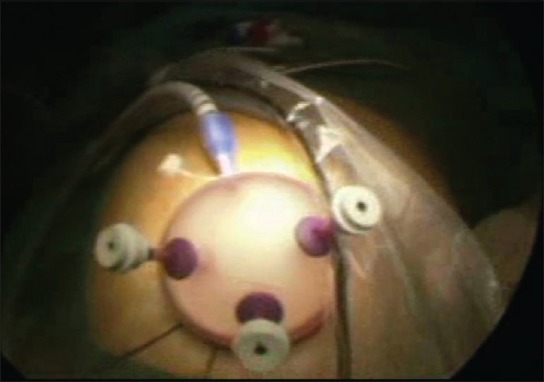

The patient was placed in the supine position. The surgeon stood between the legs of the patient and the assistant on the left side. A 3–4 cm transumbilical skin incision was created and was deepened to the linea alba, where a 4 cm fascial incision was made. The peritoneum was incised, and the GelPOINT® advanced access platform was deployed. Three 5 mm GelPOINT trokars were inserted [Figure 1]. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved to a pressure of 14 mmHg. We used a 5-mm-long, rigid, 30° video laparoscope.

Figure 1.

External shot during SILS sleeve gastrectomy

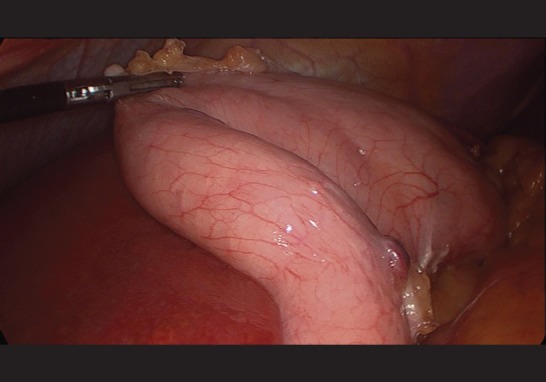

Using a 5 mm LigaSure (Covidien) and a 5 mm flexible grasper, the greater curvature of the stomach was mobilized, starting from a point 6 cm proximal to the pylorus, staying close to the wall of the stomach all the way up the greater curvature to the angle of His, dividing both gastrocolic and splenic ligaments. The mobilized portion of the greater curvature of the stomach is then taken by a 5 mm flexible grasper and pulled to the left side in the direction of the underside of the left hepatic lobe.

By lifting the stomach, the liver is automatically pulled up. This retraction of the liver facilitates further exposure of the angle of His [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

By lifting the stomach, the liver is automatically pulled up

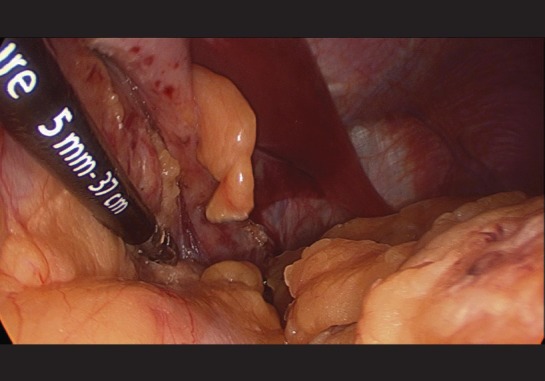

It is important to identify and mobilize the angle of His with exposure of the left crus of the diaphragm to facilitate the complete resection of the fundus [Figure 3]. Retrogastric adhesions are taken down with the LigaSure to allow complete mobilization of the stomach, eliminate any redundant posterior wall of the sleeve, and to exclude the fundus from the gastric sleeve. Once the stomach has been completely mobilized, a 36 French orogastric tube was inserted orally into the pylorus and placed against the lesser curvature. This will calibrate the size of the gastric sleeve, prevent constriction at the gastroesophageal junction, and provide a uniform shape to the entire stomach. Then, we changed one 5 mm trokar into a 12 mm trokar.

Figure 3.

Exposure of the left crus of the diaphragm to facilitate the complete resection of the fundus

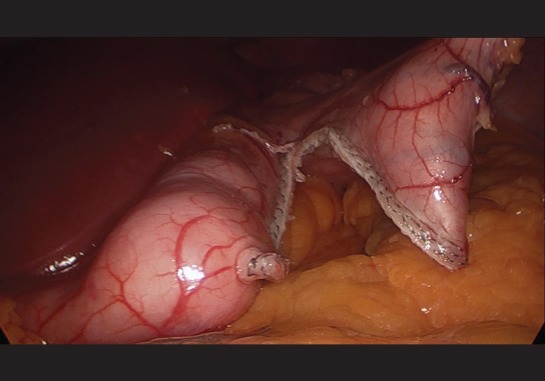

Gastric transection was started at a point 6 cm proximal to the pylorus, leaving the antrum and preserving gastric emptying [Figure 4]. A long laparoscopic reticulating 60 mm XL Endo-GIA stapler with a golden cartridge (Echelon Flex-Ethicon-Endosurgery) was inserted through a 12 mm trocar. The stapler was fired consecutively along the length of the orogastric tube until the angle of His was reached. Care must be taken not to narrow the stomach at the incisura angularis. It is important to inspect the stomach anteriorly and posteriorly to ensure no redundant posterior stomach!

Figure 4.

Gastric transection was started at a point 6 cm proximal to the pylorus

Approximately 80% of the stomach was separated. The entire staple line was inspected for bleeding. Bleeding necessitated the prompt placement of clips along the line of bleeding. Similar to the SG technique, no intraoperative leak test was employed. We did not, as a routine, leave a drain or a nasogastric tube. The resected stomach was extracted through the umbilical incision without specimen endobag. The fascial defect was closed with 0/0 absorbable sutures, and the skin was closed with an intracutaneous running suture.

An upper gastrointestinal contrast study was obtained on postoperative day 1 to rule out leaks and obstruction, and all patients were commenced on liquids as contrast study was done. Patients were discharged postoperative day number 6 and were routinely placed on a daily proton pump inhibitor for 1 month.

RESULTS

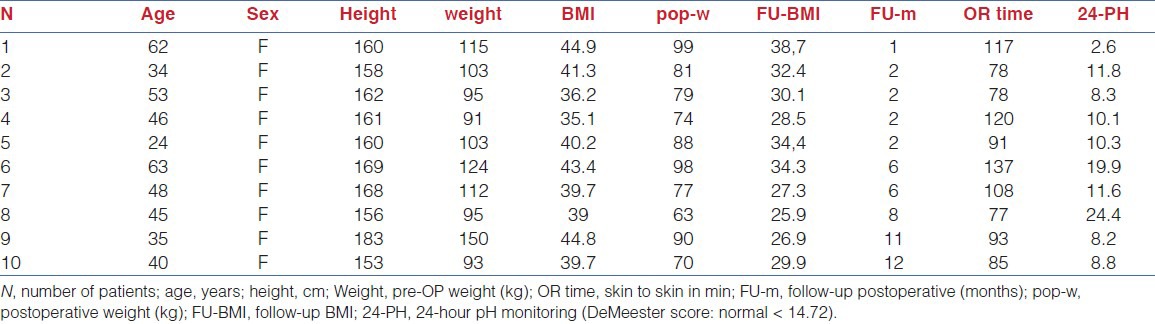

Ten SITU laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies were successfully performed with using this technique [Table 1]. Mean operative time was 98 min (range, 77-137). The mean hospital stay was 6.3 days (range, 5-7). The long stay was caused by the Austrian insurance and clearing system. Without this payment system, most patients could be discharged home on postoperative day 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of the 10 SITU sleeve gastrectomy patients

There was no mortality. No peri- or postoperative complications, especially haemorrhage or umbilical hernia, occurred. All preoperative esophageal manometries and endoscopies were without pathological findings. Only two 24-h pH monitorings showed an increased DeMeester score (>14.72), but postoperatively none of the patients had gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. The mean postoperative BMI was 30.8 kg/m2 (range, 25.9–38.7). After a mean follow-up period of 5.2 months (range, 1–12), the patients were losing a mean of 26.2 kg excess weight (range, 15–60 kg) from their initial assessment. The mean operation time was 98.4 min (range, 77–137 min). In our follow-up, all patients were very satisfied with the cosmetic outcomes and excess weight loss.

DISCUSSION

A minimally invasive approach to the surgical management of obesity has been shown to dramatically reduce perioperative morbidity through reduced blood loss, hospital stay, and wound complications.[10] Laparoscopic SG has recently been identified as an innovative approach to the surgical management of obesity. In this procedure, the greater curvature of the stomach is resected producing a narrow, tubular stomach with the size and shape of a banana. This procedure has quickly attracted considerable surgical interest because it does not require a gastrointestinal anastomosis or intestinal bypass and it is considered less technically challenging than LRYGB. SG also avoids implantation of an artificial device around the stomach in comparison to gastric banding.[11] Weight loss following SG is achieved by both restriction and hormonal modulation. First, reduction in stomach size with the sleeve resection restricts distention and increases the patient's sensation of fullness (decreasing meal portion size). This restriction is further facilitated by the natural band effect of the intact pylorus, which is maintained during the SG. Second, early evidence suggests a reduction in the hunger drive of patients undergoing SG. This may be related to decreasing serum levels of ghrelin, a hormone produced mainly by P/D1 cells lining the fundus of the human stomach which stimulates hunger.[12] As with other procedures for bariatric surgery, perioperative risk for SG appeared to be relatively low even in patients considered ‘high risk’. Moreover, the entire upper gastrointestinal tract remains accessible for endoscopic assessment. Concerns remain however, regarding the risks and important major complications associated with SG including staple line leak (1.2%), post-operative hemorrhage (3.6%), and the irreversibility of SG. Published complication rates ranged from 0% to 29% (average 11%). The overall reported mortality rate for LSG was 0.3%.[13]

The numerous advantages of laparoscopic procedures compared to the open counterparts have inspired an interest in even more minimally invasive surgical approaches. The potential advantages of SILS are related to limiting the port incisions to one site, in addition to the advantages of traditional minimally invasive surgery. The substantial reduction in abdominal wall trauma translates into less postoperative pain, a more rapid recovery, fewer wound complications, and improved cosmetic outcomes. In our series, all patients were very satisfied with the cosmetic outcomes and excess weight loss. The umbilicus is the thinnest part of abdominal wall. Therefore, access through the umbilicus minimizes the torching effect of trocars, facilitating the mobility of the instruments in different directions. When necessary, the surgeon can convert a SITU procedure into a conventional laparoscopic procedure by adding one or more conventional laparoscopic ports, thus preserving the existing standards of care.[4,5,6,7,8]

Patient selection is important for the single-incision bariatric surgery, and some patients are not well-suited for these procedure. Most authors do not recommend this procedure for those with a BMI greater than 50 because of abundant abdominal fat that makes surgery very difficult. In addition, due to the longer-than-normal working distance between the angle of His and the umbilicus in the SILS procedure, it should be avoided in tall patients (height > 180 cm).[4] Despite its advantages in SILS bariatric surgery, the small umbilical incision tends to “crowd” the trocars in a very limited surgical field. The resulting reduced instrument triangulation and inability to retract tissue by the assistant make this procedure more arduous. In addition, handling a hypertrophic liver and abundant visceral fat is also critical in morbidly obese patients. Longer endoscope, longer graspers and longer endocutter are also highly recommended.[4,5,6,7,8]

However, we have found that in a select group of obese patients, for example with a BMI 35–45, this procedure can be performed entirely through the umbilicus without the need for any extraumbilical incisions. Primarily, the gastroesophageal junction can be easily reached by using transumbilical instruments. Second, the liver is relatively small and can be retracted by using the mobilized stomach. Finally, working from posterior, rather than in front of, the stomach achieves excellent exposure during this procedure.

Confident, multiport laparoscopic skills are critical to safely introduce this new technique without added complications. This approach has a unique learning curve, principally to overcome the technical challenges of navigating instruments within a limited range of motion.[5] As this procedure requires far more skill than a conventional laparoscopic multiport surgery, it should only be undertaken by SILS and bariatric experienced surgeons.

CONCLUSION

Single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is safe, technically feasible, and reproducible, and it is a feasible alternative to standard laparoscopic SG. We are satisfied with our initial experience, and we plan to continue using this approach whenever possible. However, this approach should be tailored according to the patient's body habitus and liver size.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Himpens J, Dapri D, Cadière GB. A prospective randomized study between laparoscopic gastric banding and laparoscopic isolated sleeve gastrectomy: Results after 1 and 3 years. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1450–56. doi: 10.1381/096089206778869933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon Han S, Kim WW, Oh JH. Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at 1 year in morbidly obese Korean patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1469–75. doi: 10.1381/096089205774859227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Till H, Blücher W, Kiess W. Efficacy of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) as a stand-alone technique for children with morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1047–49. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang CK. Single-incision laparoscopic bariatric surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saber AA, Elgamal MH, Itawi EA, Rao AJ. Single incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SILS): A novel technique. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1338–42. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saber AA, El-Ghazaly TH, Elian A. Single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:755–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0179. discussion 759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CK, Tsai JC, Lo CH, Houng JY, Chen YS, Chi SC, et al. Preliminary surgical results of single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:391–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galvani CA, Choh M, Gorodner MV. Single-incision sleeve gastrectomy using a novel technique for liver retraction. JSLS. 2010;14:228–33. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12785289144278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakdawala MA, Muda NH, Goel S, Bhasker A. Single-Incision sleeve gastrectomy versus conventional laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy-a randomised pilot study. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1664–70. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, Arango A, Cole CJ, Lee SJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: A randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2001;234:279–89. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00002. discussion 289-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frezza EE. Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. The future procedure of choice? Surg Today. 2007;37:275–81. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer FB, Reza Hoda MA, Bohdjalian A, Felberbauer FX, Zacherl J, Wenzl E, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric banding: Effects on plasma ghrelin levels. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1024–9. doi: 10.1381/0960892054621125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi X, Karmali S, Sharma AM, Birch DW. A review of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1171–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]