Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a rare variant of cholecystitis and reported incidence of XGC varies from different geographic region from 0.7% -9%. Most of the clinicians are not aware of the pathology and less evidence is available regarding the optimal treatment of this less common form of cholecystitis in the present era of laparoscopic surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in a tertiary care university hospital from 1989 to 2009. Histopathologically confirmed XGC study patients (N=27) were compared with non-Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (NXGC) control group (N=27). The outcomes variables were operative time, complication rate and laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy conversion rate. The study group (XGC) was further divided in to three sub groups; group I open cholecystectomy (OC), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy (LCO) for comparative analysis to identify the significant variables.

RESULTS:

During the study period 6878 underwent cholecystectomy including open cholecystectomy in 2309 and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 4569 patients. Histopathology confirmed xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis in 30 patients (0.43% of all cholecystectomies) and 27 patients qualified for the inclusion criterion. Gallbladder carcinoma was reported in 100 patients (1.45%) during the study period and no association was found with XGC. The mean age of patients with XGC was 49.8 year (range: 29-79), with male to female ratio of 1:3. The most common clinical features were abdominal pain and tenderness in right hypochondrium. Biliary colic and acute cholecystitis were the most common preoperative diagnosis. Ultrasonogram was performed in all patients and CT scan abdomen in 5 patients. In study population (XGC), 10 were patients in group I, 8 in group II and 9 in group III. Conversion rate from laparoscopy to open was 53 % (n=9), surgical site infection rate of 14.8% (n=4) and common bile duct injury occurred one patient in open cholecystectomy group (3.7%). Statistically significant differences between group I and group II were raised total leukocyte count: 10.6±3.05 vs. 7.05±1.8 (P-Value 0.02) and duration of surgery in minutes: 248.75±165 vs. 109±39.7 (P-Value 0.04). The differences between group III and group II were duration of surgery in minutes: 208.75±58 vs. 109±39.7 (P-Value 0.03) and duration of symptoms in days: 3±1.8 vs. 9.8±8.8 (P-Value 0.04). The mean hospital stay in group I was 9.7 days, group II 5.6 days and in group III 10.5 days. Two patients underwent extended cholecystectomy based on clinical suspicion of carcinoma. No mortality was observed in this study population. Duration of surgery was higher in XGC group as compared to controls (NXGC) (203±129 vs.128±4, p-value=0.008) and no statistically significant difference in incidence proportion of operative complication rate were observed among the group (25.9% vs. 14.8%, p-value=0.25. Laparoscopic surgery was introduced in 1994 and 17 patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and higher conversion rate from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy was observed in 17 study group (XGC) as compared to 27 Control group (NXGC) 53%vs.3.3% with P-value of < 0.023.

CONCLUSION:

XGC is a rare entity of cholecystitis and preoperative diagnosis is a challenging task. Difficult dissection was encountered in open as well in laparoscopic cholecystectomy with increased operation time. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was carried out with high conversion rate to improve the safety of procedure. Per operative clinical suspicion of malignancy was high but no association of XGC was found with gallbladder carcinoma, therefore frozen section is recommended before embarking on radical surgery.

Keywords: Bile duct injury, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis

INTRODUCTION

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a rare variant of common pathology of gallbladder. XGC develops as a process of intense acute or chronic inflammation, characterized by asymmetrical thickening of gallbladder wall with formation of nodule.[1] The dense inflation is responsible for dens adhesion to the surrounding viscera; therefore, the condition has been related to difficult cholecystectomy.[2] The clinical features could be of chronic or acute cholecystitis and the radiological imaging could mimic gallbladder carcinoma with mass in the wall.

The reported incidence of XGC varies from different geographic region from 0.7% -9%.[3]

The pathogenesis of XGC remains speculative. It has been said that the foreign body reaction against the extravagation of bile may be the fundamental process to initiate the process and may mimic the pathology of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, where obstruction with stasis is an important etiology. Infection and delayed hypersensitivity through cell mediated immunity have also been proposed for the pathogenesis.[4,5]

The preoperative diagnosis is often difficult and intraoperative frozen-section is required to rule out gallbladder carcinoma and at the same time most of the clinicians are not familiar with XGC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has gained wide acceptance for the treatment of acute and chronic cholecystitis but the role of LC in XGC is questionable because of high conversion rate and high incidence of intraoperative complications. The reported conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy has been from 5-80% and intraoperative complication rate of up to 31% has been reported in the available literature.[6]

In this retrospective cohort study the incidence complications and laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy conversion rate was calculated for the patients with the diagnosis of XGC and compared with patients who underwent cholecystectomy for NXGC during the same time period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this retrospective cohort study the patients with histopathologically confirmed xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) were compared with reference cohort group with the diagnosis of non-xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (NXGC), randomly selected patients from available list of all the patients underwent cholecystectomy for symptomatic gall stones between 1989 and 2009. The list of patients with the diagnosis of XGC and NXGC were retrieved through the hospital medical record system using ICD-9 code 575.10. All histopathology reports of gall bladder were reviewed from hospital online record system to identify patients with XGC and NXGC. The patients with incomplete records were excluded from the study group. A subgroup of patients with XGC who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy when introduced in 1994 onwards and randomly selected control group (NXGC) to compare incidence proportion of complications and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy. The study group (XGC) was further divided in to three sub-groups according to treatment modality: Group I. Open cholecystectomy (OC), group II, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and group III. Laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy (LOC).

The data were gathered on the predesigned Performa; includes clinical presentation, findings on examination, laboratory investigations, findings on radiological imaging and histopathology report. It also contains operative procedure, operative time, intra and post-operative complications, length of hospital stay and 30 days morbidity and mortality.

The statistical analysis was done on a software SPSS-17. Frequency tables were generated for variables with calculation of mean and range. The appropriate statistical test was applied according to the data categories to identify the differences among and P-Value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

During the study period 7616 patients were managed for cholecystitis includes: Acute calculus cholecystitis in1930, acute acalculous cholecystitis in 495, chronic calculus cholecystitis in 5000 and chronic acalculous cholecystitis in 191 patients. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 4569 patients and 2309 underwent open cholecystectomy.

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis were reported in 30 patients. From the reported cases them three were excluded because of incomplete medical record. Among the 27 patients with XGC, there were 17 female and 4 male. Mean age at presentation was 48.8 year (range of 29-78). The most common clinical presentation were abdominal pain (n=25), nausea and vomiting (n=10), fever (n=9) and jaundice (n=4). Physical examination revealed tenderness in right hypochondrium in 21 patients.

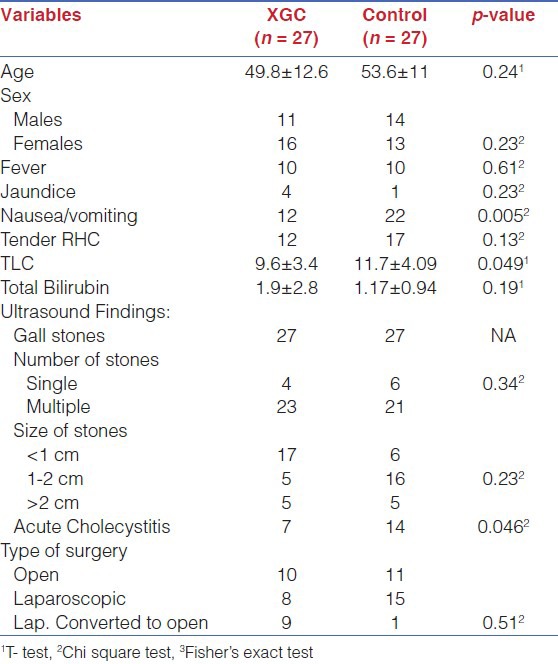

Clinical spectrum and diagnostic findings are summarized in the Table 1. Significantly greater number of controls (NXGC) presented with nausea, vomiting, raised total leukocyte counts and acute cholecystitis as compared to the study group (XGC).

Table 1.

Clinical Variables of all the patients

Ultrasonography showed gall stones in all patients and additional information were acute cholecystitis (n=7), Choledocholithiasis (n=1), empyema GB (n=2), perforated GB (n=1) and GB mass (n=2).Ultrasound was unable to diagnosis XGC in this series. CT scan was done in five patients and was reported as GB mass (n=2), choledocholithiasis (n=1) cholelithiasis with thick GB wall (n=2) and with suspicion of carcinoma GB in two of the patients with GB mass. The preoperative diagnosis was: Biliary colic (n=14), acute cholecystitis (n=10), obstructive jaundice (n=1) and GB mass (n=2) with suspicion of malignancy.

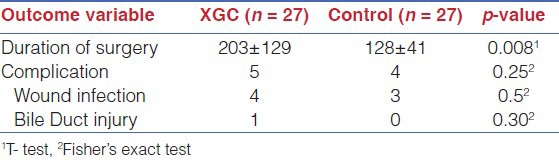

Duration of surgery was higher in XGC as compared to controls (203±129 vs.128±4, p-value=0.008), whereas no statistically significant difference was found between study and control groups for the incidence proportion of complications [Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcome variables of all the patients

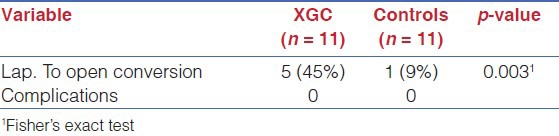

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was introduced in this institution in 1994 and prior to this all 8 patients with XGC were treated by standard open cholecystectomy through right sub-costal incision and the additional procedure were extended cholecystectomy (n=2), Choledocholithotomy (n=1) and choledochojejunostomy (n=1). After 1994 all patients (n=17) except two patients with GB mass underwent attempted laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 9 required conversion (rate=53%) to open cholecystectomy. Statistically significant high laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy was noted when compared the study group(XGC) with control group (NXGC) ,incidence rate of 53%vs.9 % with P-value of < 0.023 and no intra operative complications was reported after 1994 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Sub group analysis of patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy after 1994 for the outcomes

Difficult dissection was encountered in both LC and OC, because of dense adhesion to surrounding viscera, thick fibrotic GB and distorted anatomy of callout's triangle. Minor common bile duct injury occurred in one patient (3%) in OC and was repaired over T-tube. Four patients (14%) in OC group developed surgical site infection. No morbidity was noticed in LC and LOC group with high conversion rate and was able to achieve optimal results. This could prove the safety of LC in patients with XGC in the hands of experienced clinician following the principal of careful dissection and low threshold for conversion to open cholecystectomy.

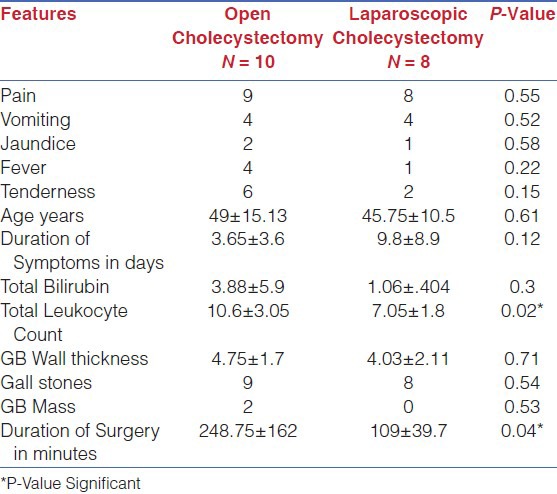

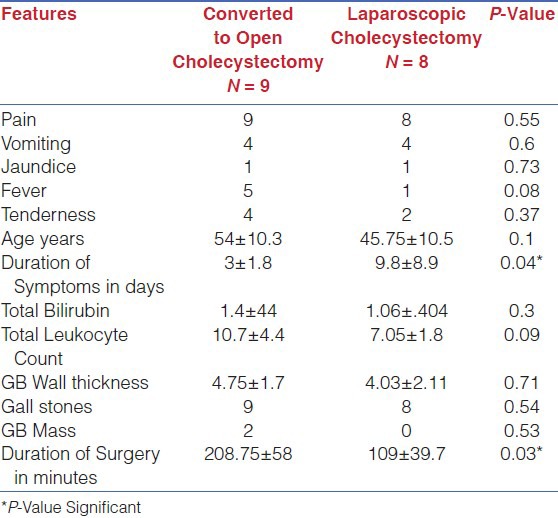

Comparative analysis [Table 4] of the study group (XGC) was performed. The statistically significant differences between group I (OC) and group II (LC) were total leukocyte count increased in group I (P-Value 0.02) and duration of surgery in minutes was also significantly increased in open cholecystectomy patients (P-Value 0.04). Comparative analysis of group II (LC) and group III (LOC) was also performed [Table 5] to look for the differences among the group. The significant variables identified were increased duration of symptoms in days in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients (P-Value 0.04) and increased duration of surgery in patients required conversion to open cholecystectomy (P-Value 0.03).

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of Open VS laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in XGC

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of Converted to open VS laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in XGC

DISCUSSION

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis is a rare variant, first describe by McCoy in 1978 representing 0.7 to13.2% of all cholecystitis.[1,2] This review demonstrated an incidence of 0.43% among all of the cholecystectomies carried out during a 20 year period at an urban university hospital.

The clinical presentation of XGC is reported to be more common in male gender.[1,6] However this study population XGC presented predominantly in females with male to female ratio of 1:3 and this could be because gall stones are more common in women. The average age of presentation was 49.8 year and the average age reported in other series were older[1,6] and the explanation could be cholelithiasis develops at earlier age in Indian-subcontinent and this one of the explanation for high incidence of GB cancer in this region.

The relation of XGC with lithiasis ha been reported to be 85-96%[1,6] and this speculate calculi as an initial step to initiate the process of this condition by obstruction of the GB and mimic the pathogenesis of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. The review being reported here revealed that 96% of XGC was associated with lithiasis. The role of ultrasonography in the preoperative diagnosis of XGC is reported with variable results. GB wall thickening with intramural hypo echoic nodule could be helpful in the diagnosis.[7,8] In this review ultrasound was performed in all 27 patients and beside cholelithiasis, thickening of GB wall was reported in 7 patients, GB mass in 2,GB perforation in 2 and acute cholecystitis in 7 patients. Preoperative ultrasound was not helpful in this series to make the diagnosis of XGC, except in two patients with GB mass where CT scan was suggested. There is an emerging role of CT scan in the preoperative diagnosis of XGC and to differentiate from GB carcinoma with reported excellent accuracy.[9,10,11] In this review CT scan was done in 5 patients and revealed GB mass in 2 with suspicion of GB cancer, thick wall BG in 2 and choledocholithiasis in 1 patient. The two patients with GB mass underwent extended open cholecystectomy and no evidence of carcinoma on histopathology. Similar report of misdiagnosis has been reported by Xingji et al[12] and others[13] have strongly suggested intraoperative frozen-section to ensure optimal surgical treatment. Although there are reported high radiological and intraoperative finding of GB carcinoma in patients with XGC, but the actual incidence is low from 0.2%-3%.[1,3] During the study period 100 patients had histopathological diagnosis of GB carcinoma but we found no association with XGC and therefore reemphasize the importance of radiological imaging and intraoperative frozen-section to provide optimal surgical treatment.

The intense chronic inflammatory process is the hallmark of XGC may cause dense adhesion with the neighboring organ and cause fistula formation, stricture and external compression. In this review, XGC presented with obstructive jaundice in 4 patients; 3 patients were having Mirizzi syndrome type I with external compression on common bile duct and were treated with open partial cholecystectomy. One patient had cholecystoduodenal fistula without gall stone ileus and was treated with open cholecystectomy and primary repair of duodenal fistula. Similar results have been reported by other investigators.[1,14,15]

Before 1994 all 8 patients with XGC were treated with standard open cholecystectomy through right sub-costal incision. Distorted anatomy and difficult dissection was encountered resulted in minor CBD injury in one patient (rate=3%) repaired primarily and 4 patient developed post-operative surgical site infections (14%). After the option of laparoscopic cholecystectomy became routine, 17 patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This procedure had to be converted to an open procedure in 9 cases (53%). The indications for conversion were difficult dissection, dense adhesion of gallbladder to surround organ and unable to identify clearly callout's triangle. No patient required conversion due to major hemorrhage, suspected biliary injury or suspicion of malignancy. Three patients underwent open cholecystectomy because of suspected GB carcinoma in 2 and associated choledocholithisis in one case. The other investigators have also reported difficult dissection in open cholecystectomy for XGC with 15%-28% morbidity includes intraoperative biliary injury and post-operative biliary fistulas.[2] The literature about the role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in XGC is scanty and the reported conversion rate is 19%-80% and the reasons were similar to this review except suspicion of GB cancer was higher.[1,6,16] Most of the authors agree that laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be considered after patient selection, clear visualization of anatomy and with low threshold for conversion to avoid major organ injuries.[6,16]

We found higher operative time and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy in study group (XGC) as compared to other pathologies (control group), but the incidence of complications was not significant. Our findings suggest that surgery in XGC is difficult due to adhesions with surrounding structures.

In this study, we have included control group for comparison of outcomes and operative rate in the same review. Although there is a small sample size, but it depicts the rarity of disease as evident from 0.34% prevalence of XGC at our urban tertiary care hospital over a period of 20 years. The prevalence might have been higher than this, if all the patients were to undergo cholecystectomy. Male preponderance of XGC has been reported;[6] however, we didn’t find such association in our study. The average age of presentation in our study was 49.8 year, which is younger than the previously reported series[6] This could be explained by the fact that cholelithiasis develops at earlier age in Indian-subcontinent and carrying stones for longer period might have led to XGC, and the same explanation has been proposed for high incidence of GB cancer in this region.

Control group was associated more with nausea/vomiting, raised TLC and acute cholecystitis. This could have been due to random selection of patients from the list; or an alternate explanation could be that persistent chronic inflammation in XGC might had led to fibrosis of GB wall with low propensity for acute inflammatory changes and its consequences.

The role of ultrasonography in the preoperative diagnosis of XGC is reported with variable results. GB wall thickening with intramural hypo echoic nodule could be helpful in the diagnosis.[7,8] In this review, ultrasound was performed in all 27 patients of XGC and besides Cholelithiasis; thickening of GB wall was reported in 7 patients, GB mass in 2,GB perforation in 2 and acute cholecystitis in 7 patients. Presence of wall thickness was consistent with diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Hence, preoperative ultrasound was not helpful in this series to make the diagnosis of XGC, except in two patients with GB mass where CT scan was suggested. There is an emerging role of CT scan in the preoperative diagnosis of XGC and to differentiate from GB carcinoma with reported excellent accuracy.[9,10] In the same study, intramural hypo attenuated nodules, discernible mucosal lining and presence of gallstones were differentially noted in XGC patient; the last two were found to be independently associated with XGC on multivariate analysis.[10] Whereas, no significant difference in the pattern of gallbladder wall thickening (diffuse or focal) and the presence of changes outside the gallbladder. In this review, CT scan was done in five patients and revealed GB mass in two with suspicion of GB cancer, thick wall GB in 2 and choledocholithiasis in 1 patient.

The two patients with GB mass underwent extended open cholecystectomy, and were found to have carcinoma on histopathology. The association of XGC with carcinoma GB has been reported in early studies, but dixit el al has concluded no association of XGC with carcinoma gall bladder from a high incidence area.[1] In our study, two out of 30 patients (6.6%) had carcinoma gall bladder, which was reported in CT scan and extended open cholecystectomy was done. This association may be strenuous as both, carcinoma and XGC, share same cause i.e. gall stones. But nonetheless, high index of suspicion for carcinoma should be kept with low threshold for intraoperative frozen section.

We found lower rate of conversion from laparoscopic to open (53%) than Guzman et al (80%). This might be explained from learning curve of laparoscopic cholecystectomy as our study included cases up to 2009 as compared to Guzman et al, who have reported cases up to 2002.[2] This shows that LC has been becoming more and more successful in XGC with the increasing learning curve. However, as a rule of thumb, the enthusiasm of completing LC with complications should never surpass patient safety and in such case it is always prudent to convert early.

In our study, the incidence of complications was higher in XGC (18.9%) as compared to control group NXGC, although statistically not significant. one of the patient had minor common bile duct injury in during open cholecystectomy and was repaired over T-Tube as compared to controls (although statistically insignificant. This incidence is higher than previously reported rate of 13.5% by Guzman et al,[6] but the same authors reported a complication rate of 31% in another study conducted exclusively on XGC patients managed laparoscopically.[2] In contrast to this, all the complications in our study occurred before the advent of LC as depicted by subgroup analysis [Table 2]. Moreover, we successfully completed total cholecystectomy in all the patients as compared to Guzman et al,[2] who reported 64% partial cholecystectomy in patients who underwent LC. So, our study support LC in XGC and we consider it a safe and successful procedure. Its success rate would even increase more with the increasing learning curve.

At times, XGC mimics carcinoma to such an extent, that misdiagnosis of carcinoma (instead of XGC) preoperatively has been reported;[11] leading to inadvertent extended cholecystectomy. Intraoperative frozen-section has been suggested to ensure optimal surgical treatment. Frozen section may also be misleading since the result depends on from where the specimen of frozen is being sent. So, if there is a suspicion of malignancy, it would be pragmatic to start with open cholecystectomy and send the entire gall bladder for frozen and proceed further based on its report.

Before 1994, all 7 patients were treated with standard open cholecystectomy through right sub costal incision and distorted anatomy and difficult dissection was encountered, resulted in minor CBD injury in three patients (10%), which was repaired primarily and four patients developed post-operative surgical site infections. After the option of laparoscopic cholecystectomy became routine, 11 patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This procedure had to be converted to an open procedure in 5 cases (45%). The indications for conversion were difficult dissection, dense adhesion of gallbladder to surround organ and inability to visualize the calot's triangle vividly. No patient required conversion due to major hemorrhage, suspected biliary injury or suspicion of malignancy. The literature about the role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in XGC is scanty and the reported conversion rate is 19%-80%[6,12] and the reasons were similar to this review except suspicion of GB cancer was higher. Most of the authors agree that laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be considered, with low threshold for conversion to avoid major organ injuries in case of difficult anatomy and hard to negotiate adhesions.

CONCLUSION

XGC is a rare variant of cholecystitis, difficult to diagnose preoperatively even on CT scan, with features mimicking carcinoma; but no such association has been found. It carries a higher laparoscopic to open conversion rate, which is decreasing with the rising learning curve, and no complications with laparoscopic cholecystectomy in our series validates the safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in XGC.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilberto Guzman-Valdivia. Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis: 15 years Experience. World J Surg. 2004;28:254–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7161-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilberto Guzman-Valdivia. Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis in Laparoscopic Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:494–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixit VK, Parakash A, Gupta A, Pandey M, Gautam A, Kumar M, Shukla VK. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998 May;43(5):940–2. doi: 10.1023/a:1018802028193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mori M, Watanabe M, Sakuma M, Tsutsumi Y. Infectious etiology of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: Immunohistochemical identification of bacterial antigens in the xanthogranulomatous lesions. Pathol Int. 1999;49:849–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seiko Sawada, Kenichi Harada, Kumiko Isse, Yasunori Sato, Motoko sasaki, Yasuharu Kaizaki, Yasi Nakanuma. Involvement of Escherichia coli in pathogenesis of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis with scavenger receptor class A and CXCL16-CXCR6 interaction. Pathol Int. 2007;57:652–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon AH, Matsui Y, Uemura Y. Surgical Procedures and Histopathologic Findings for Patients with Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim PN, Ha HK, Kim YH, Lee MG, Kim MH, Auh YH. US Findings of Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:290–2. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(98)80129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muguruma N, Okamura S, Okahisa T, Shibata H, Ito S, Yagi K. Endoscopic sonograpgy in the Diagnosis of Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:347–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199907/08)27:6<347::aid-jcu7>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuto R, Kiyosue H, Komatsu E, Matsumoto S, Kawano K, Kondo Y, et al. Ct and MRI findings of Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis: Correlation with pathologic findings. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:440–6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1931-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama K, Ozawa S, Ueno M, Hayami S, Hirono S, Ina S, et al. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: The use of preoperative CT findings to differentiate it from gallbladder carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:333–8. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goshima S, Chang S, Wang JH, Kanematsu M, Bae KT, Federle MP. Xanthogranulomatous Cholecystitis: Diagnostic performance of CT to differentiate from gallbladder carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:e79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xianji Luo, Tiang Yang, Baihe Zhang, Xiaoqing Jiang, Mengcho Wu. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis misdiagnosed as gallbladder carcinoma: Retrospective analysis of 10 cases. Chinese-German J Clin Oncol. 2007;6:215–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinocy J, Lange A, König C, Kaiserling E, Becker HD, Kröber SM. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis resembling carcinoma with extensive tumour infiltration of liver and colon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:48–51. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KC, Yamazaki O, Horii K, Hamba H, Higaki I, Hirata S, et al. Mirrizi syndrome caused by xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1997;27:757–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02384992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishna RP, Kumar A, Singh RK, Sikora S, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Xanthogranulomatous inflamantio stricture of extrahepatic biliary tract: Presentation and surgical management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:836–41. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srikanth G, Kumar A, Khare R, Siddappa L, Gupta A, Sikora SS, et al. Should Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy be performed in patients with thick-walled gallbladder? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:40–4. doi: 10.1007/s00534-003-0866-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]