Background: In obesity, enlarged adipocytes become hypoxic, which inhibits adipocyte differentiation.

Results: Hypoxia induces the expression of Wnt1 and Wnt10b in both human and mouse adipogenic cells in a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2α-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Hypoxia enhances the secretion of Wnt ligands, which trigger Wnt signaling in the neighboring cells.

Significance: Wnt10b is a novel HIF-2α-specific target gene and a paracrine factor in hypoxia.

Keywords: Adipogenesis, Hypoxia, Hypoxia-inducible Factor, Hypoxia-inducible Factor (HIF), Wnt Signaling, HIF-2α, Wnt1, Wnt10b

Abstract

Adipocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy in obesity can lead to many changes in adipose tissue, such as hypoxia, metabolic dysregulation, and enhanced secretion of cytokines. In this study, hypoxia increased the expression of Wnt10b in both human and mouse adipogenic cells, but not in hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2α-deficient adipogenic cells. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α, bound to the Wnt10b enhancer region as well as upstream of the Wnt1 gene, which is encoded by an antisense strand of the Wnt10b gene. Hypoxia-conditioned medium (H-CM) induced phosphorylation of lipoprotein-receptor-related protein 6 as well as β-catenin-dependent gene expression in normoxic cells, which suggests that H-CM contains canonical Wnt signals. Furthermore, adipogenesis of both human mesenchymal stem cells and mouse preadipocytes was inhibited by H-CM even under normoxic conditions. These results suggest that O2 concentration gradients influence the formation of Wnt ligand gradients, which are involved in the regulation of pluripotency, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation.

Introduction

Direct measurements of O2 concentrations in adult tissues have revealed hypoxic conditions characterized by O2 levels ranging from 2 to 9% (14.4–64.8 mmHg). Tissue hypoxia is caused by an imbalance between oxygen supply and metabolic demand. Within the microenvironment of adult stem cells, which are often found distal to blood vessels, O2 concentrations are estimated to be as low as 1% (7.2 mmHg) (1–3). In obesity, enlarged adipocytes become hypoxic because they expand up to 150–200 μm in diameter, which exceeds the normal O2 diffusion distance of ∼100 μm from the vessels (4, 5). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)2 plays a major role in adaptive responses to hypoxia, including angiogenesis, vasodilation, and glycolysis, by inducing target genes such as those encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inducible nitric oxide synthase, and many glycolytic enzymes. HIF is a heterodimeric transcription factor consisting of two subunits, α and β. HIF binds to E-box-like DNA sequences within its target genes, named hypoxia-responsive elements (HREs). The first HIF-α isoform, HIF-1α, was identified by HRE affinity purification, whereas HIF-2α/EPAS-1 was discovered in a homology search (1, 6).

In contrast to the constitutive HIF-β subunit, the two HIF-α isoforms are ubiquitinated and rapidly degraded under normoxia and are stabilized under hypoxia. Although both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are co-expressed in many cell types and share many target genes, HIF-1α and HIF-2α knock-out mice both display embryonic lethality (7, 8). Following exposure to hypoxia, HIF-1α protein levels increase maximally after 4 h and decrease after 24 h, whereas HIF-2α protein levels steadily increase after 24 h. Thus, acute hypoxia preferentially increases HIF-1α protein levels, whereas chronic hypoxia enhances HIF-2α protein levels (9, 10). Chromatin binding analysis in MCF7 breast cancer cells revealed higher levels of HIF-1α occupancy in most of the hypoxia-induced genes and especially in glycolytic pathway genes, whereas HIF-2α showed preferential binding for only a few genes such as OCT4, Arginase1, and cyclin D1 (11–13).

Wingless/integration (Wnt) ligands are secreted glycoproteins that control tissue remodeling by regulating the proliferation and differentiation of specific cell types (14, 15). Canonical Wnts bind to transmembrane receptors, frizzled (Fzl) and lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 or 6 (LRP5/6). These interactions between canonical Wnts and their receptors cause dissociation of the Axin-APC-GSK3b complex, resulting in stabilization of β-catenin. Stabilized β-catenin then enters the nucleus and promotes the transcription of Wnt target genes by interacting with its transcriptional partner, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (LEF)/T cell factor (TCF) (16). A canonical Wnt isoform, Wnt10b, maintains preadipocytes in an undifferentiated state through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and by repressing adipogenesis (17–19). In this study, we found that the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus is occupied by HIF-2α but not by HIF-1α. In addition, we demonstrate for the first time that hypoxia induces Wnt10b expression in a HIF-2α-dependent manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Insulin, dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine (IBMX), Oil Red-O, and puromycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bovine calf serum was purchased from Life Technologies. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) were obtained from Lonza (Charles City, IA). Antibody against β-catenin was purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti-phospho-cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) (Ser-133), anti-CREB, anti-phospho-LRP6 (Ser-1490), and anti-LRP6 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-HIF-1α and anti-HIF-2α antibodies were purchased from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Antibodies against CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP)α (14AA), C/EBPβ (H-7), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ (E-8), Wnt10b (H-70), and Axin1 (H-98), and the chemical compound IWP2, were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K9K14Ac, and anti-14-3-3γ antibodies were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). An antibody against Wnt1 was acquired from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Recombinant mouse and human Wnt3a and recombinant human DKK1 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Super 8×TOP Flash reporter plasmid (8×TCF-Luc), which encodes the luciferase gene driven by eight copies of the TCF binding site, and mouse Wnt10b cDNA (NM_011718) were purchased from Addgene Inc. (Cambridge, MA). The Wnt10b promoter and the enhancer-driven luciferase reporters, mWnt10b-Luc (−715 to +286 bp) and mWnt10b-Luc (−2569 to +286 bp), were constructed by subcloning PCR products of the mouse Wnt10b gene from −715 to +286 bp and from −2,569 to +286 bp, respectively, into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI).

Cell Culture and Adipocyte Differentiation

3T3-L1 (ATCC, catalog number CL-173) preadipocytes and NIH3T3 (ATCC, catalog number CRL-1658) cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) bovine calf serum. For differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes, postconfluent 3T3-L1 cells were exposed to a standard mixture (MDI) composed of 0.5 mm IBMX, 1 μm dexamethasone, and 5 μg/ml insulin in DMEM containing 10% FBS for the first 2 days. Cells were then cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and containing 5 μg/ml insulin for the following 2 days, after which they were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The medium was changed every 2 days. hADSCs were obtained from two different donors (catalog number 510070, lot numbers 1199 and 2152, Invitrogen) and expanded in basal medium. For adipogenesis, hADSCs were cultured in adipogenic medium (catalog number A1007001, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HIF-2α knock-out mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from HIF-2α−/− embryos at embryonic day 12.5 and cultured in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) FBS as described previously (20). Hypoxic treatment of cells was achieved by incubating the cells in an anaerobic incubator (<0.5% O2, Model 1029, Forma Scientific, Inc.) or an InVivo2 200 hypoxia work station (5% or 3% O2, Ruskin). Accumulated lipids in adipocytes were visualized and measured by staining with Oil Red-O, as described previously (21).

Conditioned Medium (CM)

Normoxic preadipocyte-CM (Np-CM) was spent medium harvested from cultured mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocytes for 2 days before MDI treatment. Normoxia-CM (N-CM), physiological hypoxia (3% O2)-CM (H3-CM), and severe hypoxia (<0.5% O2)-CM (H-CM) were spent media harvested from mouse 3T3-L1 cells cultured under normoxia (21% O2), physiological hypoxia (3% O2), and severe hypoxia (<0.5% O2) for 2 days between day 4 and day 6 after MDI treatment, respectively. Hypoxic adipocyte-CM (Ha-CM) was spent medium harvested from mature mouse adipocytes cultured under hypoxia for 2 days between day 10 and day 12 after MDI treatment. Hu-CM and Hu-CM+IWP2 were spent media harvested from cultured undifferentiated hADSCs under hypoxia (<0.5% O2 for 3 days) in the absence or presence of IWP2 (5 μm). Wnt3a-CM was spent medium harvested from confluent Wnt3a-expressing L929 cells. Conditioned media were filtered through 0.22-μm filter paper and stored at 4 °C.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Steady-state mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7000 real-time PCR system. The Ct value of a target mRNA was normalized against the Ct value of endogenous 18 S rRNA (ΔCt = Cttarget − Ct18 S). Ct is the threshold cycle of quantitative PCR (qPCR) defined by an ABI 7000 real-time PCR system. The relative mRNA level of a target gene is obtained by 2−ΔΔCt; ΔΔCt = ΔCttreated value − Ctuntreated value. Copy numbers of Wnt10b mRNA were determined by using a plasmid encoding mouse Wnt10b cDNA (accession number: NM_011718, 334–1503 bp) as a standard PCR template for the standard curve method as described previously (22). Copy number was calculated using the equation: 1 μg of 1000 bp of DNA = 9.1 × 1011 molecules. Primer sequences used are as follows: mWnt1 (NM_021279), forward 5′-CCT CCA CGA ACC TGT TGA CG-3′, reverse 5′-GTT CTG TCG GAT CAG TCG CC-3′; mWnt10b (NM_011718), forward 5′-ACC ACG ACA TGG ACT TCG GAG A-3′, reverse 5′-CCG CTT CAG GTT TTC CGT TAC C-3′; mArginase1 (NM_007482), forward 5′-AAC ACG GCA GTG GCT TTA ACC-3′, reverse 5′-GGT TTT CAT GTG GCG CAT TC-3′; mAxin2 (NM_015732), forward 5′-ATG GAG TCC CTC CTT ACC GCA T-3′, reverse 5′-GTT CCA CAG GCG TCA TCT CCT T-3′; hWnt1 (NM_021279), forward 5′-CGG CGT TTA TCT TCG CTA TCA-3′, reverse 5′-GCA GGA TTC GAT GGA ACC TTC T-3′; hWnt10b (NM_011718), forward 5′-TGC GAA TCC ACA ACA ACA GG-3′, reverse 5′-ATG TCT TGA ACT GGC AGC TGC-3′; hBNIP3 (NM_004052), forward 5′-TGC TGC TCT CTC ATT TGC TG-3′, reverse 5′-GAC TCC AGT TCT TCA TCA AAA GGT-3′.

Reporter Analysis

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates, and after 24 h, the cells were transfected with Wnt10b reporter constructs (250 ng) or with HIF-1α (200 ng) or HIF-2α (200 ng) expression vectors, together with the pRL-CMV plasmid (50 ng) using the Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). After 24 h, transfected cells were cultured in normoxic or hypoxic conditions with or without MDI or Bt2-cAMP (300 μm). NIH3T3 or 293 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates, and after 24 h, the cells were transfected with 250 ng of Wnt/β-catenin reporter plasmid (Super 8×TOPFlash, Addgene Inc.). After 24 h, the transfected cells were treated with 1 ml of the indicated CM, which was used to culture 3T3-L1 or hADSCs in normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The control medium was DMEM containing 10% FBS. After exposure to the CM for 24 h, the transfected cells were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized against Renilla luciferase activity.

Knockdown Using Retrovirus Infection

HIF-1α or HIF-2α was knocked down in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes using a retrovirus infection system, pSIREN-RetroQ (BD Biosciences), as described previously (21). Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences against mouse HIF-1α and mouse HIF-2α were 5′-TGT GAG CTC ACA TCT TGA TT-3′ and 5′-GAC AGA ATC TTG GAA CTG A-3′, respectively.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR Analysis

Cells were fixed and harvested for ChIP analysis, as described previously (21). The cross-linked cells were resuspended in SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.1)). Cell lysates were sonicated, and the A260 of the sonicated lysate solution was measured to ensure that similar amounts of chromatin were used in each sample. Next, the sonicated lysate was diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mm EDTA, 16.7 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 167 mm NaCl). The diluted lysates were immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of anti-phospho-CREB (Ser-133), anti-CREB, anti-HIF-1α, anti-HIF-2α, anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K9K14Ac, anti-H3, or control IgG antibody. Immunoprecipitates were washed once each with low salt buffer, high salt buffer, and LiCl wash buffer and then washed twice with TE buffer. The immunocomplexes were eluted with 300 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 m NaHCO3) and reverse cross-linked by adding 0.2 m NaCl at 65 °C. Input values were obtained from samples treated in the same manner, except that the immunoprecipitation steps were not performed. The isolated DNAs were quantitated by using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7000 real-time PCR system. Primer sequences used are as follows: mWnt10b (−15 kb), forward 5′-AAA AGG GTT CGA GCC GAC TC-3′, reverse 5′-CCT GAT GTT TGC CCA CCC TA-3′; mWnt10b (−11 kb), forward 5′-TTC CTT CTC TGT CCA GCC GT-3′, reverse 5′-TCT GTC CCC CCT ACG CTG T-3′; mWnt10b (−7 kb), forward 5′-TGA GAG TGC TGG ATC CTT TGG-3′, reverse 5′-GCA TGG CTC ATC GGT TAA GAG-3′; mWnt10b (−5 kb), forward 5′-TCA CCA CGA TGC ACA CTC AA-3′, reverse 5′-AGC ACA TGC AAA GGC CAG A-3′; mWnt10b (−2.4 kb), forward 5′-CAG CGG CTT AGC AAC AGA TG-3′, reverse 5′-AAT CAA GCA ACT GAG GCG GT-3′; mWnt10b (−1.4 kb), forward 5′-GGC CTT CTT CCC CTA AAT GG-3′, reverse 5′-TTG ATG AGG GTG CTG GAG C-3′; mWnt10b (+0.1 kb), forward 5′-CTG CGT TCT CCT GGT CAA GT-3′, reverse 5′-CTG CTC GAC CTA ACT CAC GG-3′; mBnip3 (−0.3 kb), forward 5′-GCC CCC AGA CTC TTC CCT AC-3′, reverse 5′-GGA GGG CGG CTG TTT TTA AG-3′; mArginase1 (−2.9 kb), forward 5′-CTT TGT CAG CAG GGC AAG ACT-3′, reverse 5′-CCA AAG TGG CAC AAC TCA CG-3′; mDEC2 (−0.3 kb), forward 5′-ACG TTC CGC ACG TGA GCT G-3′, reverse 5′-ACA CGC ACT GCG CTG GTA GT-3′. The Ct value of a target gene in the immunoprecipitated DNA sample was normalized against the Ct value of the target gene in the input DNA (ΔCt = Ctsample − Ctinput). The relative amount of the target gene in an isolated DNA sample is obtained by 2−ΔCt. The percentage of input (% input) indicates the value of 100 × 2−ΔCt.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative measurements were performed in at least two independent experiments. Data were presented as the mean ± S.D. or mean ± S.E. For comparisons between two groups, p values were calculated using paired two-tailed Student's t tests. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

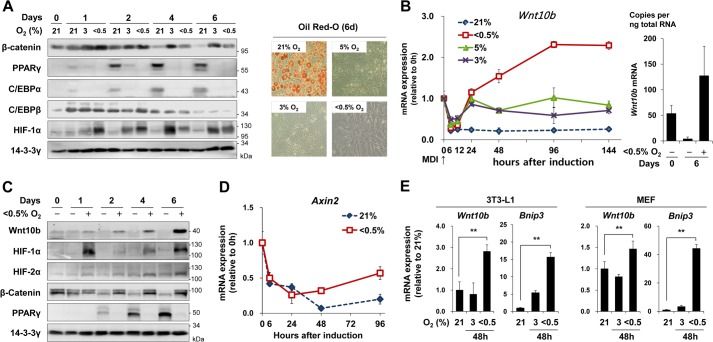

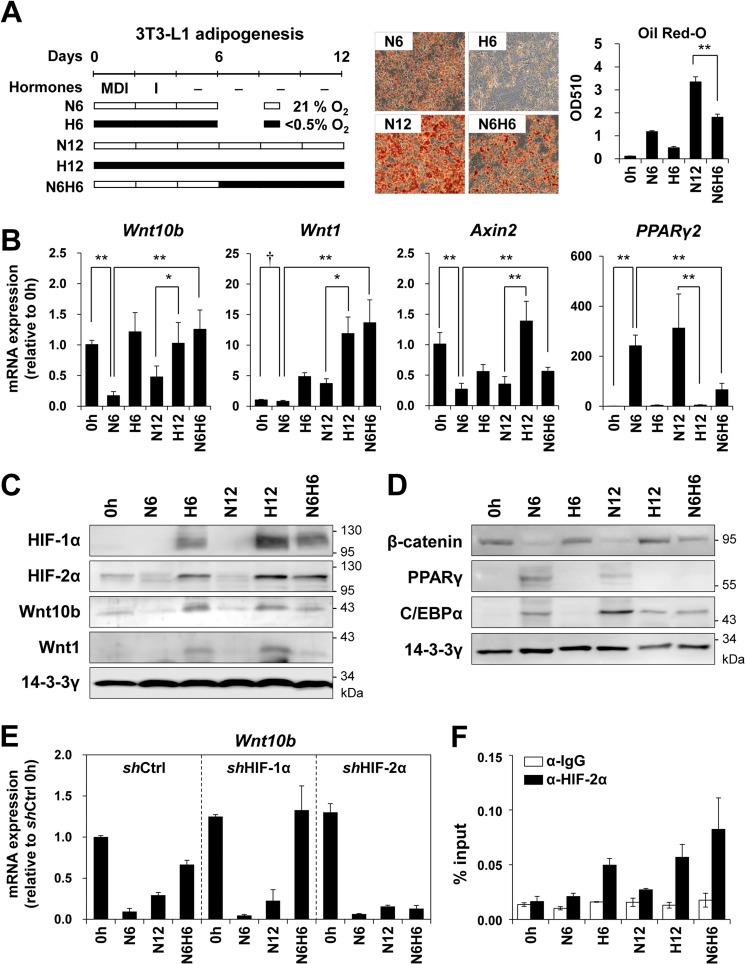

Hypoxia Increases Expression of the Wnt10b Gene in Mouse 3T3-L1 Cells

Previously, we showed that both physiological (3% O2) and severe hypoxia (<0.5% O2) inhibit adipogenesis of mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocytes by blocking the induction of C/EBPα and PPARγ adipogenic transcription factors, which are the target genes of C/EBPβ (21). During adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells, the level of β-catenin protein gradually decreased, whereas under hypoxia, it remained stable. The level of HIF-1α protein was also stabilized under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1A). Following treatment with adipogenesis-inducing hormones (IBMX, Dexamethasone, Insulin, MDI) for 6 h, Wnt10b expression initially decreased to the level usually found in mature adipocytes regardless of the oxygen concentration. After treatment for 24 h and under physiological hypoxia (3–5% O2), Wnt10b expression was comparable with the level found in preadipocytes, whereas after treatment for 48 h and under severe hypoxia (<0.5% O2), the level of Wnt10b expression was greater than that in preadipocytes (Fig. 1, B and C). Similar to Wnt10b expression, the mRNA levels of Axin2, a target gene of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, initially decreased and then gradually recovered after 24 h of hypoxic exposure (Fig. 1D). Exposure to severe hypoxia (<0.5% O2, for 48 h) also caused an increase in mRNA levels of Wnt10b as well as in BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3), a hypoxia-inducible gene in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and MEFs (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Hypoxic induction of Wnt10b. A–D, postconfluent mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into mature adipocytes under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (5%, 3%, or <0.5% O2) conditions for the indicated times. A, Western blot analysis was performed with anti-β-catenin, anti-PPARγ, anti-C/EBPα, anti-C/EBPβ, and anti-HIF-1α antibodies (left panel). Lipid droplets were stained with Oil Red-O at 6 days after MDI treatment (right panel). B, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b mRNA levels, which were normalized against 18 S rRNA levels (left panel). Copy numbers of Wnt10b mRNA at 6 days after MDI treatment were determined by using a standard curve method as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ (right panel). C, Western blot analysis was performed with anti-Wnt10b, anti-HIF-1α, anti-HIF-2α, anti-β-catenin, and anti-PPARγ antibodies. 14-3-3γ was used as a loading control. D, qRT-PCR analysis of Axin2 mRNA levels, which were normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. E, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b or Bnip3 mRNA in undifferentiated 3T3-L1 or MEF cells incubated under hypoxia (3% or <0.5% O2) for 48 h without MDI. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). p values (**) < 0.01 between control and an indicated experimental group are shown.

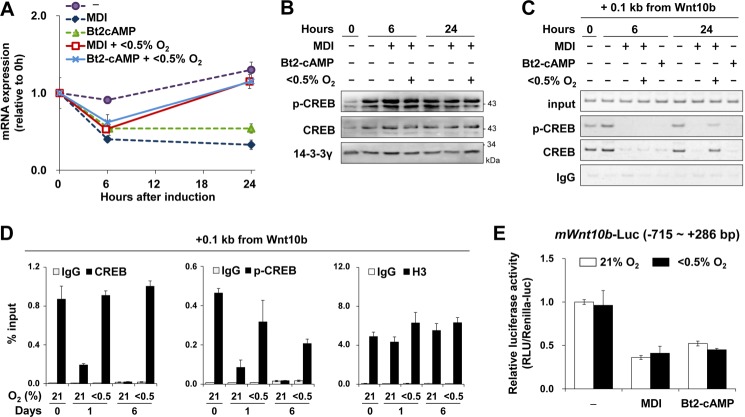

IBMX, a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is responsible for suppressing Wnt10b expression by activating cAMP signaling (23, 24). Bt2-cAMP, a cAMP mimetic, was sufficient to repress Wnt10b within 6 h, even under hypoxia. However, after 24 h, hypoxia facilitated the recovery of Wnt10b expression even in the presence of MDI or Bt2-cAMP. Hypoxia did not alter the phosphorylation of CREB (Fig. 2, A and B). Instead, hypoxic exposure for 24 h enhanced the binding of CREB to the Wnt10b promoter, which was inhibited by MDI or Bt2-cAMP (Fig. 2, C and D). The reporter assay revealed that both MDI and Bt2-cAMP repressed Wnt10b promoter activity (from −715 to +286 bp), which contains a cAMP-response element. In contrast to endogenous Wnt10b expression, hypoxia did not lead to recovery of the Wnt10b promoter activity (Fig. 2E), implying that hypoxia indirectly increased CREB binding to the Wnt10b promoter through other regulatory regions.

FIGURE 2.

Hypoxia maintains CREB occupancy on the Wnt10b promoter. A–C, postconfluent 3T3-L1 cells were treated with MDI or Bt2-cAMP (300 μm) for the indicated times under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (<0.5% O2) conditions. A, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b mRNA levels. B, Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phospho-CREB (p-CREB) and anti-CREB antibodies. 14-3-3γ was used as a loading control. C, ChIP analysis of CREB or phospho-CREB binding to the Wnt10b promoter in 3T3-L1 cells using a primer set covering −4 to +100 bp of the Wnt10b gene. An anti-mouse IgG antibody was used as a negative control. Input values were obtained from samples treated in the same way except that the immunoprecipitation steps were not performed. D, ChIP analysis of CREB binding, phospho-CREB binding, or histone 3 (H3) levels on the Wnt10b promoter in 3T3-L1 cells by using the mouse Wnt10b promoter primer (−4 to +100 bp). E, luciferase activity analysis of 3T3-L1 cells that were transfected with a reporter plasmid encoding luciferase driven by the mouse Wnt10b promoter (−715 to +286 bp). After transient transfection, 3T3-L1 cells were treated with MDI or Bt2-cAMP (300 μm) under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h. Luciferase activity was normalized against Renilla luciferase activity. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). p values (**) < 0.01 between control and an indicated experimental group are shown.

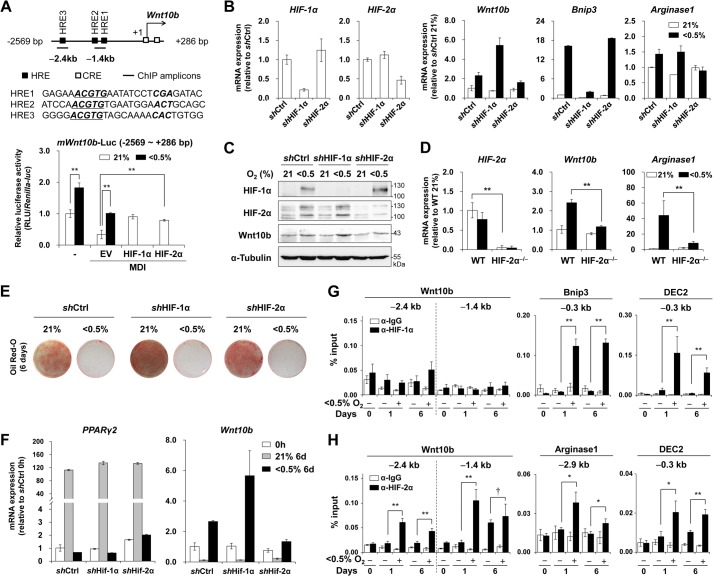

Hypoxic Induction of Wnt10b Expression Is HIF-2α-dependent

We generated a reporter plasmid encoding a luciferase gene driven by the upstream region of the Wnt10b gene (−2,569 bp to +286 bp) containing three putative HREs, which were identified around −2.4 or −1.4 kb upstream of the Wnt10b gene. MDI repressed this reporter gene, whereas hypoxia promoted its expression. Co-transfection of HIF-1α or HIF-2α increased the expression of this reporter gene even in MDI-treated normoxic cells (Fig. 3A). We generated stable HIF-1α or HIF-2α knockdown 3T3-L1 preadipocytes by infecting the cells with a retrovirus encoding shRNA against either HIF-1α or HIF-2α. Hypoxia failed to increase the expression of Bnip3, a HIF-1α-specific target gene, in HIF-1α knockdown (shHIF-1α) cells, and of Arginase1, a HIF-2α-specific target gene, in HIF-2α knockdown (shHIF-2α) cells (Fig. 3B). Hypoxia induced expression of Wnt10b in shHIF-1α cells to a greater extent than in wild-type 3T3-L1 cells, but had no effect on Wnt10b induction in shHIF-2α cells, suggesting that HIF-2α is essential for hypoxic induction of Wnt10b (Fig. 3, B and C). In addition, hypoxia failed to induce the expression of Wnt10b in HIF-2α knock-out MEFs (Fig. 3D). Neither HIF-1α nor HIF-2α knockdown altered adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells in response to MDI. Furthermore, hypoxic repression of adipogenesis was not reversed by either HIF-1α or HIF-2α knockdown, suggesting that hypoxia utilized additional pathways to block adipogenesis in addition to HIF-2α-dependent Wnt10b expression (Fig. 3, E and F) (21). ChIP analysis showed that HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α, bound to the Wnt10b HREs. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α bound to their common target gene, DEC2, as well as their specific target genes, Bnip3 and Arginase1, respectively (Fig. 3, G and H).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of HIF-α on the expression of Wnt10b. A, three putative HRE sites (closed boxes), two CREB-binding sites (open boxes), and two ChIP amplicons (−2.4 and −1.4 kb) are marked on the Wnt10b gene (upper panel). Luciferase activity analysis of 3T3-L1 cells transfected with a reporter plasmid mWnt10b-Luc (−2569 to +286 bp) encoding luciferase driven by the Wnt10b enhancer and promoter (−2,569 to +286 bp). After transient transfection with this reporter plasmid along with a plasmid encoding HIF-1α or HIF-2α, 3T3-L1 cells were treated with MDI under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h (lower panel). Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. B and C, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were infected with a retrovirus encoding shRNA against mouse HIF-1α (shHIF-1α), mouse HIF-2α (shHIF-2α), or control shRNA (shCtrl), as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ The cells were then incubated under normoxia or hypoxia (<0.5% O2) for 48 h. B, qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated mRNA levels. C, Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins in shHIF-1α or shHIF-2α 3T3-L1 cells. D, qRT-PCR of the indicated mRNA levels in wild-type or HIF-2α knock-out MEFs incubated under normoxia or hypoxia for 48 h. Values are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. E and F, control shRNA, shHIF-1α, and shHIF-2α 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated into adipocytes under normoxia or hypoxia (<0.5% O2) for 6 days. E, Oil Red-O staining of lipid droplets. F, qRT-PCR analyses of PPARγ2 or Wnt10b mRNA levels were measured and normalized with 18 S rRNA. G and H, ChIP-qPCR analysis of HIF-1α (G) or HIF-2α (H) occupancy on the Wnt10b gene in 3T3-L1 cells at the indicated times after adipogenesis induction under normoxia or hypoxia (<0.5% O2). Immunoprecipitated genomic DNAs were amplified by qPCR with two primer sets around −2.4 or −1.4 kb from the transcription start site of the Wnt10b gene. The values on the y axis indicate the percentage of input as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ Primer sets for the Bnip3 (−0.3 kb), Arginase1 (−2.9 kb), and DEC2 (−0.3 kb) genes are shown under ”Experimental Procedures.“ Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of two or three independent experiments. p values < 0.01 (**), < 0.05 (*), and > 0.1 (†) are shown.

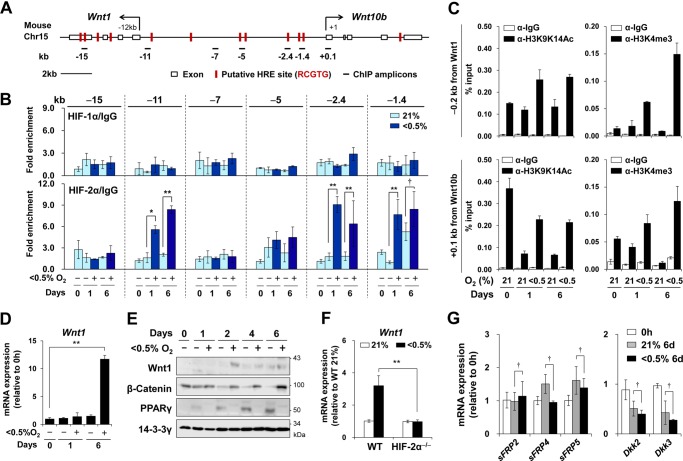

HIF-2α Occupies the Wnt10b/Wnt1 Locus in Mouse Chromosome 15

An extended search up to −15 kb upstream of the mouse Wnt10b gene in chromosome 15 revealed additional HREs near the Wnt1 gene, which is encoded by an antisense strand of the Wnt10b gene (Fig. 4A). The Wnt1 coding region was flanked by several HREs. ChIP analysis using primer sets covering the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus showed that HIF-2α bound to HREs located −0.2 kb from the Wnt1 transcription start site (−11 kb from the Wnt10b gene), whereas HIF-2α did not bind to the region located −7.0 kb from this site, where no HREs were found. By contrast, HIF-1α binding was not observed in the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus (Fig. 4B). ChIP analysis using anti-H3K9K14Ac or anti-H3K4me3 antibodies revealed that, on the transcription start site of either the Wnt10b or the Wnt1 gene, hypoxic exposure increased the acetylation of Lys-9/Lys-14 residues and trimethylation of the Lys-4 residue of histone3, which are found in active chromatin domains (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

HIF-2α occupancy on the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus in mouse chromosome 15. A, indication of putative 12 HREs on the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus of mouse chromosome 15 (98,771–98,793 kb). B and C, the following experiments were performed using mouse 3T3-L1 cells at the indicated times after adipogenic hormone induction under either normoxia or hypoxia (<0.5% O2). B, ChIP-qPCR analysis of HIF-1α (upper panel) or HIF-2α (lower panel) occupancy on the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus. The values on the y axis indicate the relative amount of a target gene precipitated by an HIF-α antibody as compared with the amount of the same target gene precipitated by IgG. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. C, ChIP-qPCR analysis of histone modifications on the promoter regions of Wnt1 and Wnt10b. Genomic DNA immunoprecipitated using the anti-H3K9K14Ac or anti-H3K4me3 antibodies was amplified by qPCR with two primer sets around −11 kb (−0.2 kb from Wnt1, upper panel) or +0.1 kb (lower panel) from the transcription start site of the Wnt10b gene, as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ p values < 0.01 (**), < 0.05 (*), and > 0.1 (†) are shown. D and E, postconfluent mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into mature adipocytes under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (<0.5% O2) conditions for the indicated times. D, Wnt1 mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. E, Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins. F, qRT-PCR of Wnt1 mRNA in wild-type or HIF-2α−/− MEFs that were incubated under normoxia or hypoxia (<0.5% O2) for 48 h. Values are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. G, qRT-PCR analysis of sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK2, and DKK3 in 3T3-L1 cells treated as described above. mRNA levels were normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. p values < 0.01 (**), < 0.05 (*), and > 0.1 (†) are shown. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed no change in Wnt1 expression during adipogenesis, whereas it was induced by prolonged hypoxia (Fig. 4D). Western analysis also confirmed that hypoxia increased the levels of Wnt1 protein (Fig. 4E). Hypoxic induction of Wnt1 was not observed in HIF-2α knock-out MEFs, suggesting that hypoxia induces Wnt1 expression in a HIF-2α-dependent manner (Fig. 4F). The Dickkopf (DKK) family of secreted proteins and the secreted frizzled-related protein (sFRP) family prevent Wnts from activating their membrane-bound LRP/Fzl receptors (6). We tested whether hypoxia alters the expression of sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK2, or DKK3 in adipogenic cells (25, 26) and found no significant changes (Fig. 4G).

Hypoxia Induces Expression of Wnt10b and Wnt1 Genes in Mature Adipocytes

To test whether hypoxia induces Wnt10b expression in 3T3-L1 mature adipocytes, we differentiated 3T3-L1 cells into mature adipocytes and then exposed them to hypoxia as indicated in Fig. 5A. Hypoxic exposure inhibited lipid accumulation in mature adipocytes (Fig. 5A) and promoted expression of Wnt10b, Wnt1, and Axin2, whereas PPARγ2 was repressed (Fig. 5B). In addition, hypoxia in mature adipocytes led to stabilization of HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins and expression of Wnt10b and Wnt1 proteins (Fig. 5C). Hypoxic exposure also increased the protein stability of β-catenin, but decreased the protein levels of PPARγ and C/EBPα in mature adipocytes (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, hypoxia failed to increase the expression of Wnt10b in mature adipocytes derived from shHIF-2α 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 5E). ChIP analysis confirmed that hypoxic exposure increased HIF-2α binding to HREs within the Wnt10b gene in mature mouse adipocytes (Fig. 5F).

FIGURE 5.

Hypoxic induction of Wnt10b and Wnt1 in 3T3-L1 mature adipocytes. A, a schematic diagram indicating the experimental designs for cell treatments. N6H6 treatment indicated that postconfluent mouse 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated into adipocytes under normoxia (N, 21% O2) for 6 days and then cultured under hypoxia (H, <0.5% O2) for the following 6 days (left panel). Right panel, microscopic images and quantification of Oil Red-O-stained lipid droplets in 3T3-L1 cells, which were treated as indicated in the diagram. B, qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated mRNA levels. C and D, Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins in 3T3-L1 cells treated as shown. E, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b mRNA in control shRNA (shCtrl), shHIF-1α, and shHIF-2α 3T3-L1 cells, cultured as described in A. F, ChIP-qPCR analysis of HIF-2α occupancy on the HREs at −1.4 kb upstream of the transcription start site of the Wnt10b gene in 3T3-L1 cells treated as described above. p values < 0.01 (**) and < 0.05 (*) are shown.

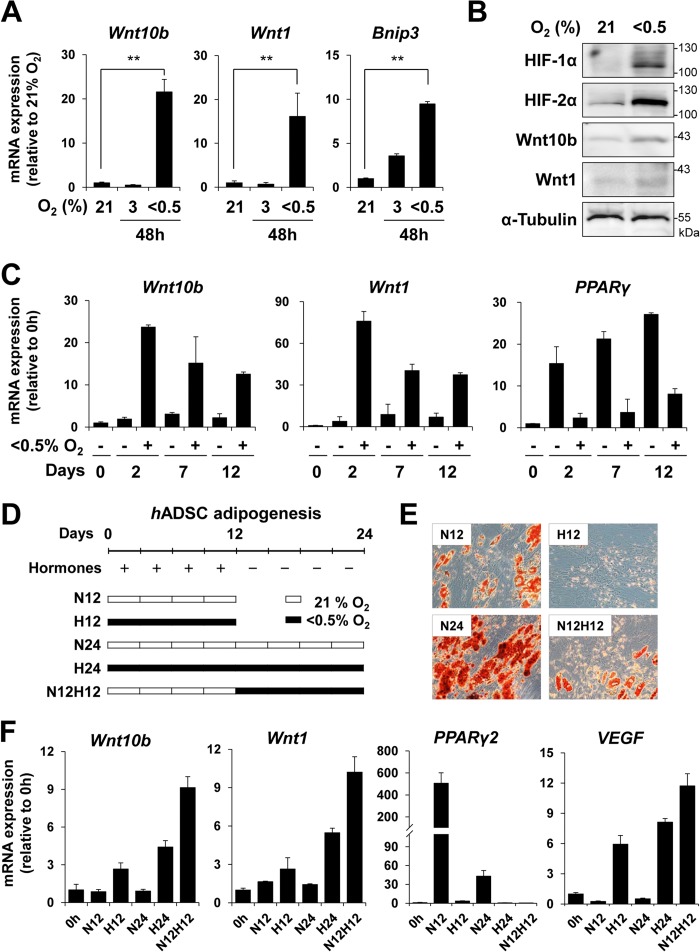

Similarly to the mouse Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus, the human Wnt1 gene is encoded by an antisense strand of the Wnt10b gene in chromosome 12q13. Upon exposure to hypoxia, expression of both Wnt10b and Wnt1 was induced in hADSCs (Fig. 6, A–C). We induced the differentiation of hADSCs into mature adipocytes for 12 days and exposed them to hypoxia for an additional 12 days as indicated in Fig. 6, D and E. Hypoxia promoted the expression of both Wnt10b and Wnt1 in mature adipocytes derived from hADSCs (Fig. 6F).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of hypoxia on Wnt10b and Wnt1 expression in hADSCs. A, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b, Wnt1, and Bnip3 in undifferentiated hADSCs that were exposed to hypoxia (3% or <0. 5% O2) for 48 h. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of two independent experiments. B, Western blot analysis of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, Wnt10b, and Wnt1 in undifferentiated hADSCs that were exposed to hypoxia (<0.5% O2) for 48 h. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. C, hADSCs were differentiated into adipocytes with an adipogenic mixture (Invitrogen) under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (<0.5% O2) conditions for the indicated number of days. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to detect Wnt10b, Wnt1, and PPARγ mRNA levels during adipocyte differentiation of hADSCs. D, the experimental designs for adipocyte differentiation of hADSCs. N12H12 treatment indicated that hADSCs were differentiated into adipocytes under normoxia (N, 21% O2) for 12 days and then cultured under hypoxia (H, <0.5% O2) for the following 12 days. E, lipid droplets in hADSCs were visualized by Oil Red-O staining. F, qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt10b, Wnt1, PPARγ2, and VEGF in hADSCs treated as indicated above. mRNA levels were normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. p values (**) < 0.01 are shown.

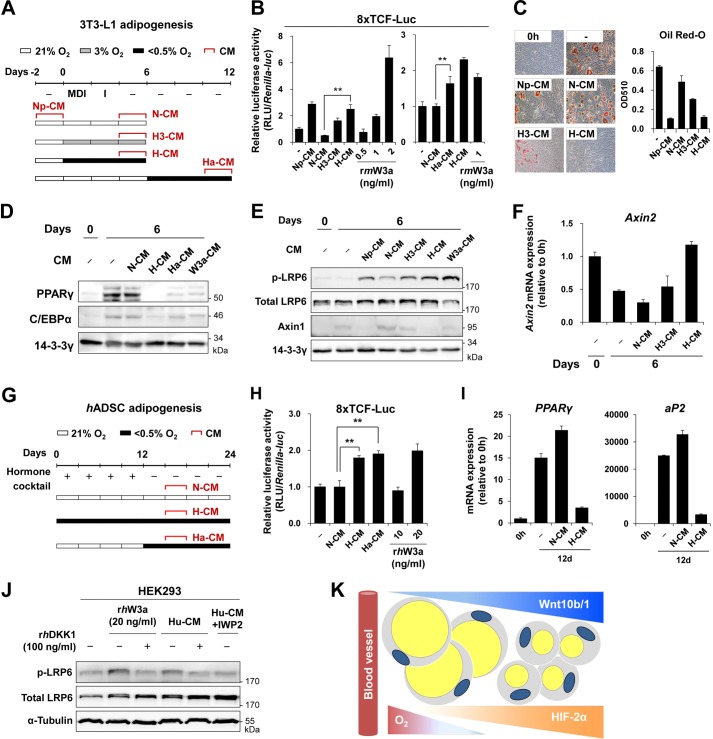

H-CM Contains Wnt Signals

H-CM, N-CM, and Np-CM were spent media harvested from adipocytes or preadipocytes cultured under hypoxic or normoxic conditions (Fig. 7A). To test whether hypoxic cells secrete Wnt ligands into the culture media, we transfected NIH3T3 cells with a reporter plasmid encoding luciferase driven by β-catenin/TCF binding sites and then treated cells with the various CM for 24 h under normoxic conditions. Based on luciferase activity, H-CM and Ha-CM displayed Wnt activity of ∼1–1.25 ng/ml recombinant mouse Wnt3a protein (rmW3a) (Fig. 7B). We next induced adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes cultured under normoxic conditions for 6 days in various culture media. Oil Red-O staining showed that MDI in N-CM induced lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells comparable with that in fresh medium, but MDI in H-CM did not (Fig. 7C). Treatment with H-CM, Ha-CM, and Wnt3a-CM prevented MDI-mediated induction of PPARγ and C/EBPα expression (Fig. 7D). In addition, treatment with H-CM or Wnt3a-CM increased the phosphorylation of the serine residue at position 1490 in LRP6, reduced the Axin1 protein level, and elevated the Axin2 mRNA level (Fig. 7, E and F). These findings suggest that H-CM contains canonical Wnt signals, which can induce the phosphorylation of LRP6, destabilization of Axin1 protein, and expression of Axin2. In addition, H-CM and Ha-CM from cultured hADSCs contained Wnt signals and inhibited adipogenesis of hADSCs (Fig. 7, G–I).

FIGURE 7.

Wnt signals in H-CM. A, a schematic diagram indicating the experimental designs for obtaining the CM (details under “Experimental Procedures”). B, luciferase activity analysis of NIH3T3 cells that were transfected with 8×TCF-Luc and then treated with the indicated CM or recombinant mouse Wnt3a protein (rmW3a) under normoxia for 24 h. C–F, 3T3-L1 cells were induced to undergo adipogenesis using the indicated CM under normoxia for 6 days. C, microscopic images and quantification of Oil Red-O-stained lipid droplets in 3T3-L1 cells. D, Western blot analysis of PPARγ and C/EBPα protein levels. E, Western blot analysis of phospho-LRP6, LRP6, and Axin1 levels. 14-3-3γ was used as a loading control. F, Axin2 mRNA levels were detected by qRT-PCR analysis and normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. G, hADSCs were differentiated into adipocytes by using an adipogenic mixture under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (<0.5% O2) conditions. Various conditioned media were obtained as described. H, luciferase activity analysis of HEK293 cells transfected with the 8×TCF-Luc plasmid and then treated with the indicated conditioned media or with recombinant human Wnt3a protein (rhW3a) (10 or 20 ng/ml) for 24 h under normoxia. I, hADSCs were induced to differentiate into adipocytes with the indicated CM for 12 days. PPARγ and aP2 mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR and normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. J, HEK293 cells were treated with Hu-CM or Hu-CM+IWP2 as indicated under normoxia for 2 h. HEK293 cells were also treated with recombinant human Wnt3a protein (rhW3a) (20 ng/ml) for 2 h. Phosphorylated LRP6 and total LRP6 were detected by Western blot analysis. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. K, a schematic diagram describing hypothetical gradients of Wnt10b and Wnt1 in the opposite direction to the O2 gradient in a blood vessel. p values (**) < 0.01 are shown.

Hu-CM, which is CM collected from cultured undifferentiated hADSCs under hypoxia, elevated LRP6 phosphorylation in HEK293 cells. The addition of DKK1, a Wnt antagonist, prevented this Hu-CM-mediated increase of LRP6 phosphorylation (Fig. 7J). We also collected Hu-CM from hADSCs exposed to hypoxia in the presence of IWP2 (Hu-CM+IWP2), a Porcupine inhibitor. Porcupine is a membrane-bound acyltransferase that is essential for the secretion of Wnt ligands (27). Treatment with Hu-CM+IWP2 did not elevate LRP6 phosphorylation in HEK293 cells (Fig. 7J). These results indicate that, in both mouse and human adipogenic cells, hypoxia induces the expression of Wnts including Wnt10b and Wnt1, which can be secreted as paracrine factors to trigger Wnt signaling in adjacent cells.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to show that hypoxia increases the expression of Wnt10b and Wnt1 in both human and mouse adipogenic cells and that the hypoxic induction of both Wnt10b and Wnt1 depends on HIF-2α but not on HIF-1α. Most of the hypoxic target genes are induced by both HIF-1α and HIF-2α or exclusively by HIF-1α (1, 28). Wnt10b and Wnt1 belong to a small subset of hypoxic target genes that are exclusively induced by HIF-2α. Both Wnt10b and Wnt1 are canonical Wnt ligands, which trigger the stabilization of β-catenin. The stabilized β-catenin interacts with the transcriptional partners LEF/TCF to activate Wnt target gene expression. Taken together with previous findings showing that HIF-1α/β increases the expression of LEF-1 and TCF-1 (29), this study shows that hypoxia increases levels of not only Wnt downstream signaling molecules but also Wnt ligands. Our findings that H-CM elevated β-catenin/TCF-driven luciferase activity and LRP6 phosphorylation in normoxic cells and that DKK1, a Wnt antagonist, prevented H-CM from initiating Wnt signaling suggest that adipogenic cells exposed to hypoxia can secrete Wnt ligands. Because Wnt ligands can diffuse in interstitial fluid, O2 concentration gradients can rebuild gradients of Wnt ligands in these microenvironments. Having measured the diffuse average concentration of Wnts in H-CM, we postulate that those cells in close proximity to hypoxic areas are exposed to a higher local concentration of Wnt ligands than the concentration found in H-CM (Fig. 7K).

Wnt10b expression was first found to be elevated in breast cancer cell lines and was therefore classified as a proto-oncogene. Wnt10b and other canonical Wnts including Wnt1, Wnt6, and Wnt10a are regulators of mesenchymal stem cell fate and inhibit adipogenesis and stimulate osteoblastogenesis. Ectopic expression of Wnt1 and Wnt10b suppresses the expression of both C/EBPα and PPARγ2 in MDI-treated 3T3-L1 cells (30–32). However, the molecular mechanisms by which Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppresses the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ2 genes are poorly understood. Noncanonical Wnts such as Wnt5a also inhibit adipogenesis not through the β-catenin/TCF pathway, but through repression of PPARγ target genes (33, 34). Wnt5a activates an NF-κB essential modulator (Nemo)-like kinase, which phosphorylates a H3K9 methyltransferase, SET domain bifurcated 1 (SETDB1). Phosphorylated SETDB1 in turn forms a co-repressor complex with DNA-bound PPARγ to repress PPARγ target genes through H3K9 methylation (34).

Simon and colleagues (29) demonstrated that under conditions of 1.5% O2, which can maintain cell proliferation, the HIF-1α/Arnt heterodimer increases the expression of LEF-1 and TCF-1, which leads to increased sensitivity of mouse embryonic stem cells to the proliferation-inducing effects of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes G1 progression through the induction of c-Myc, which plays dual roles, such as up-regulating cyclin D and repressing the cell cycle inhibitors p27 and p21 (35). By contrast, under severe hypoxia (1% O2), cell growth is arrested at G1 phase by the induction of p27 and p21 (36, 37). Paraskeva and colleagues (38) examined whether severe hypoxia inhibits cell growth through repression of β-catenin/TCF activity. Using SW480 and HCT116 colon cancer cells with constitutively high β-catenin/TCF activity, they showed that, under conditions of 1% O2, HIF-1α competes with TCF4 for binding to β-catenin, leading to dissociation of β-catenin from TCF4. On the other hand, the β-catenin/HIF-1α interaction enhances HIF-1α-mediated transcription (38). Although hypoxia (<1% O2) induces expression of both Wnt10b and Wnt1, which promote cell cycle re-entry, mesenchymal stem cells can remain in a quiescent and undifferentiated state under severe hypoxia (3, 39). By contrast, the cell proliferation rate is enhanced more by physiological hypoxia (1.5–3% O2) than by normoxia (20% O2) (20, 29). Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms responsible for such dramatic changes in the rate of cell proliferation within such a narrow concentration range of O2 remain unknown. As paracrine factors, Wnt ligands can diffuse from a severe hypoxic area to areas in which O2 concentration is above the threshold that would permit their mitogenic effects.

In obesity, adipocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy can lead to many responses commonly associated with the growth of solid tumors, such as hypoxia, enhanced cytokine secretion, macrophage recruitment, and metabolic dysregulation (40, 41). Many studies have revealed that hypoxia increases the expression of inflammatory adipokines, including IL-6, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor type1, and adrenomedullin (4, 42, 43). The production of inflammatory adipokines has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Canonical Wnts lead to insulin resistance and dedifferentiation of adipocytes (44). Together with these findings, our results suggest that hypoxic areas in adipose tissue can cause dedifferentiation and insulin resistance by inducing Wnts as well as inflammatory adipokines.

Although HIF-1α and HIF-2α share a dimerization partner as well as many target genes, they play different roles in cell cycle regulation, metabolism, cell differentiation, and inflammation (1, 13, 45). This study proposes that the Wnt10b/Wnt1 locus is a novel HIF-2α-specific target. However, the molecular mechanisms of how this locus distinguishes HIF-2α from HIF-1α remain to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Jang-Soo Chun (Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology) for providing HIF-2α+/− mice. We thank Prof. Seong-Eon Ryu (Hanyang University), Prof. Richard K. Bruick (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), and Prof. Timothy F. Lane (University of California at Los Angeles) for providing cDNAs of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and mouse Wnt10b, respectively.

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (Grants 2011-0016318 and 2012M3A9B6055343) (to H. P.).

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- Bnip3

- BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3

- C/EBP

- CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

- CM

- conditioned medium

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- DEC

- differentiated embryo-chondrocyte

- DKK

- Dickkopf

- hADSC

- human adipose-derived stem cell

- HRE

- hypoxia-responsive element

- LEF

- lymphoid enhancer-binding factor

- LRP

- lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- sFRP

- secreted frizzled-related protein

- TCF

- T cell factor

- Wnt

- wingless/integration

- IBMX

- 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- luc

- luciferase

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- Bt2-cAMP

- dibutyryl-cAMP

- m

- mouse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Keith B., Johnson R. S., Simon M. C. (2012) HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suda T., Takubo K., Semenza G. L. (2011) Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 9, 298–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohyeldin A., Garzón-Muvdi T., Quiñones-Hinojosa A. (2010) Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 7, 150–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hosogai N., Fukuhara A., Oshima K., Miyata Y., Tanaka S., Segawa K., Furukawa S., Tochino Y., Komuro R., Matsuda M., Shimomura I. (2007) Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on adipocytokine dysregulation. Diabetes 56, 901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ye J., Gao Z., Yin J., He Q. (2007) Hypoxia is a potential risk factor for chronic inflammation and adiponectin reduction in adipose tissue of ob/ob and dietary obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 293, E1118–E1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Semenza G. L. (2012) Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 148, 399–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ryan H. E., Lo J., Johnson R. S. (1998) HIF-1α is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J. 17, 3005–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tian H., Hammer R. E., Matsumoto A. M., Russell D. W., McKnight S. L. (1998) The hypoxia-responsive transcription factor EPAS1 is essential for catecholamine homeostasis and protection against heart failure during embryonic development. Genes Dev. 12, 3320–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stiehl D. P., Bordoli M. R., Abreu-Rodríguez I., Wollenick K., Schraml P., Gradin K., Poellinger L., Kristiansen G., Wenger R. H. (2012) Non-canonical HIF-2α function drives autonomous breast cancer cell growth via an AREG-EGFR/ErbB4 autocrine loop. Oncogene 31, 2283–2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmquist-Mengelbier L., Fredlund E., Löfstedt T., Noguera R., Navarro S., Nilsson H., Pietras A., Vallon-Christersson J., Borg A., Gradin K., Poellinger L., Påhlman S. (2006) Recruitment of HIF-1α and HIF-2α to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2α promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell 10, 413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takeda N., O'Dea E. L., Doedens A., Kim J. W., Weidemann A., Stockmann C., Asagiri M., Simon M. C., Hoffmann A., Johnson R. S. (2010) Differential activation and antagonistic function of HIF-α isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO homeostasis. Genes Dev. 24, 491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Covello K. L., Kehler J., Yu H., Gordan J. D., Arsham A. M., Hu C. J., Labosky P. A., Simon M. C., Keith B. (2006) HIF-2α regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 20, 557–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schödel J., Oikonomopoulos S., Ragoussis J., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J., Mole D. R. (2011) High-resolution genome-wide mapping of HIF-binding sites by ChIP-seq. Blood 117, e207–e217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Amerongen R., Nusse R. (2009) Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development 136, 3205–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. MacDonald B. T., Tamai K., He X. (2009) Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17, 9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clevers H., Nusse R. (2012) Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isakson P., Hammarstedt A., Gustafson B., Smith U. (2009) Impaired preadipocyte differentiation in human abdominal obesity: role of Wnt, tumor necrosis factor-α, and inflammation. Diabetes 58, 1550–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Longo K. A., Kennell J. A., Ochocinska M. J., Ross S. E., Wright W. S., MacDougald O. A. (2002) Wnt signaling protects 3T3-L1 preadipocytes from apoptosis through induction of insulin-like growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38239–38244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright W. S., Longo K. A., Dolinsky V. W., Gerin I., Kang S., Bennett C. N., Chiang S. H., Prestwich T. C., Gress C., Burant C. F., Susulic V. S., MacDougald O. A. (2007) Wnt10b inhibits obesity in ob/ob and agouti mice. Diabetes 56, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parrinello S., Samper E., Krtolica A., Goldstein J., Melov S., Campisi J. (2003) Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 741–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Park Y. K., Park H. (2010) Prevention of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β DNA binding by hypoxia during adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3289–3299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giulietti A., Overbergh L., Valckx D., Decallonne B., Bouillon R., Mathieu C. (2001) An overview of real-time quantitative PCR: applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods 25, 386–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fox K. E., Colton L. A., Erickson P. F., Friedman J. E., Cha H. C., Keller P., MacDougald O. A., Klemm D. J. (2008) Regulation of cyclin D1 and Wnt10b gene expression by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein during early adipogenesis involves differential promoter methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35096–35105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bennett C. N., Ross S. E., Longo K. A., Bajnok L., Hemati N., Johnson K. W., Harrison S. D., MacDougald O. A. (2002) Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30998–31004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bovolenta P., Esteve P., Ruiz J. M., Cisneros E., Lopez-Rios J. (2008) Beyond Wnt inhibition: new functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J. Cell Sci. 121, 737–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christodoulides C., Laudes M., Cawthorn W. P., Schinner S., Soos M., O'Rahilly S., Sethi J. K., Vidal-Puig A. (2006) The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 and its receptors are coordinately regulated during early human adipogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2613–2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen B., Dodge M. E., Tang W., Lu J., Ma Z., Fan C. W., Wei S., Hao W., Kilgore J., Williams N. S., Roth M. G., Amatruda J. F., Chen C., Lum L. (2009) Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hu C. J., Wang L. Y., Chodosh L. A., Keith B., Simon M. C. (2003) Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 9361–9374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mazumdar J., O'Brien W. T., Johnson R. S., LaManna J. C., Chavez J. C., Klein P. S., Simon M. C. (2010) O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1007–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ross S. E., Hemati N., Longo K. A., Bennett C. N., Lucas P. C., Erickson R. L., MacDougald O. A. (2000) Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science 289, 950–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lane T. F., Leder P. (1997) Wnt-10b directs hypermorphic development and transformation in mammary glands of male and female mice. Oncogene 15, 2133–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cawthorn W. P., Bree A. J., Yao Y., Du B., Hemati N., Martinez-Santibañez G., MacDougald O. A. (2012) Wnt6, Wnt10a, and Wnt10b inhibit adipogenesis and stimulate osteoblastogenesis through a β-catenin-dependent mechanism. Bone 50, 477–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bilkovski R., Schulte D. M., Oberhauser F., Mauer J., Hampel B., Gutschow C., Krone W., Laudes M. (2011) Adipose tissue macrophages inhibit adipogenesis of mesenchymal precursor cells via wnt-5a in humans. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 35, 1450–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takada I., Mihara M., Suzawa M., Ohtake F., Kobayashi S., Igarashi M., Youn M. Y., Takeyama K., Nakamura T., Mezaki Y., Takezawa S., Yogiashi Y., Kitagawa H., Yamada G., Takada S., Minami Y., Shibuya H., Matsumoto K., Kato S. (2007) A histone lysine methyltransferase activated by non-canonical Wnt signalling suppresses PPAR-γ transactivation. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1273–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niehrs C., Acebron S. P. (2012) Mitotic and mitogenic Wnt signalling. EMBO J. 31, 2705–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gardner L. B., Li Q., Park M. S., Flanagan W. M., Semenza G. L., Dang C. V. (2001) Hypoxia inhibits G1/S transition through regulation of p27 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7919–7926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goda N., Ryan H. E., Khadivi B., McNulty W., Rickert R. C., Johnson R. S. (2003) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α is essential for cell cycle arrest during hypoxia. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 359–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kaidi A., Williams A. C., Paraskeva C. (2007) Interaction between β-catenin and HIF-1 promotes cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Forristal C. E., Wright K. L., Hanley N. A., Oreffo R. O., Houghton F. D. (2010) Hypoxia inducible factors regulate pluripotency and proliferation in human embryonic stem cells cultured at reduced oxygen tensions. Reproduction 139, 85–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trayhurn P. (2013) Hypoxia and adipose tissue function and dysfunction in obesity. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun K., Kusminski C. M., Scherer P. E. (2011) Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2094–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Regazzetti C., Peraldi P., Grémeaux T., Najem-Lendom R., Ben-Sahra I., Cormont M., Bost F., Le Marchand-Brustel Y., Tanti J. F., Giorgetti-Peraldi S. (2009) Hypoxia decreases insulin signaling pathways in adipocytes. Diabetes 58, 95–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halberg N., Khan T., Trujillo M. E., Wernstedt-Asterholm I., Attie A. D., Sherwani S., Wang Z. V., Landskroner-Eiger S., Dineen S., Magalang U. J., Brekken R. A., Scherer P. E. (2009) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 4467–4483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gustafson B., Smith U. (2010) Activation of canonical wingless-type MMTV integration site family (Wnt) signaling in mature adipocytes increases β-catenin levels and leads to cell dedifferentiation and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14031–14041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mole D. R., Blancher C., Copley R. R., Pollard P. J., Gleadle J. M., Ragoussis J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2009) Genome-wide association of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α DNA binding with expression profiling of hypoxia-inducible transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16767–16775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]