Abstract

Background and Purpose

The histamine H4 receptor, originally thought to signal merely through Gαi proteins, has recently been shown to also recruit and signal via β-arrestin2. Following the discovery that the reference antagonist indolecarboxamide JNJ 7777120 appears to be a partial agonist in β-arrestin2 recruitment, we have identified additional biased hH4R ligands that preferentially couple to Gαi or β-arrestin2 proteins. In this study, we explored ligand and receptor regions that are important for biased hH4R signalling.

Experimental Approach

We evaluated a series of 48 indolecarboxamides with subtle structural differences for their ability to induce hH4R-mediated Gαi protein signalling or β-arrestin2 recruitment. Subsequently, a Fingerprints for Ligands and Proteins three-dimensional quantitative structure–activity relationship analysis correlated intrinsic activity values with structural ligand requirements. Moreover, a hH4R homology model was used to identify receptor regions important for biased hH4R signalling.

Key Results

One indolecarboxamide (75) with a nitro substituent on position R7 of the aromatic ring displayed an equal preference for the Gαi and β-arrestin2 pathway and was classified as unbiased hH4R ligand. The other 47 indolecarboxamides were β-arrestin2-biased agonists. Intrinsic activities of the unbiased as well as β-arrestin2-biased indolecarboxamides to induce β-arrestin2 recruitment could be correlated with different ligand features and hH4R regions.

Conclusion and Implications

Small structural modifications resulted in diverse intrinsic activities for unbiased (75) and β-arrestin2-biased indolecarboxamides. Analysis of ligand and receptor features revealed efficacy hotspots responsible for biased-β-arrestin2 recruitment. This knowledge is useful for the design of hH4R ligands with biased intrinsic activities and aids our understanding of the mechanism of H4R activation.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed issue on Histamine Pharmacology Update. To view the other articles in this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2013.170.issue-1

Keywords: biased ligands, histamine H4 receptor, β-arrestin, indolecarboxamides, FLAP 3D-QSAR, efficacy, intrinsic activity, efficacy hotspots

Introduction

GPCRs are attractive therapeutic targets. Their presence on the cell surface allows extracellular molecules to bind and stabilize active GPCR conformations that can subsequently provoke intracellular responses. Although the overall folding of GPCRs has been known for quite a while, three-dimensional (3D) structures of several family members have only recently been elucidated (Palczewski et al., 2000; Jaakola et al., 2008; Warne et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2011b; Shimamura et al., 2011; Granier et al., 2012; Haga et al., 2012; Manglik et al., 2012). This breakthrough was one of the main reasons why the Nobel Prize 2012 for chemistry has been awarded to Drs Robert Lefkowitz and Brian Kobilka for their pioneering work on GPCRs. Knowledge on ligand–receptor interactions and their downstream effects is important to design specific compounds with less side effects (Galandrin et al., 2007). Both inactive and active GPCR structures are currently available but we are not yet able to predict ligand efficacy on the design table. This prediction is further complicated by the realization that multiple active receptor conformations exist, which couple to multiple downstream effector proteins and pathways with distinct propensities (Kenakin, 2003; Bohn and McDonald, 2010; Reiter et al., 2012). The idea that some ligands may preferentially stabilize different conformation led to the identification of biased ligands, in which an agonist in pathway A can be an antagonist in pathway B (Violin et al., 2010). Biased GPCR signalling clearly further complicates drug discovery efforts, but also holds the promise to design specific biased ligands that antagonize adverse signalling routes while stimulating beneficial responses (Rajagopal et al., 2010; DeWire and Violin, 2011; Kenakin, 2011; Reiter et al., 2012).

The human histamine H4 receptor (hH4R) belongs to the class A GPCR family and is considered an important receptor in immune and inflammatory processes (Leurs et al., 2009; Zampeli and Tiligada, 2009). Since its discovery in 2000, the hH4R has been shown to signal via heterotrimeric Gαi proteins (Nakamura et al., 2000; Oda et al., 2000; Coge et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2001; Morse et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2001). However, the reference antagonist JNJ 7777120 (Thurmond et al., 2004) was recently identified as partial agonist in a β-arrestin2 recruitment assay (Rosethorne and Charlton, 2011). Subsequent analysis of 31 known H4R ligands revealed both Gαi protein and β-arrestin2-biased ligands that covered different chemical classes (Nijmeijer et al., 2012). Interestingly, all five tested indolecarboxamides (JNJ 7777120 analogues) in that study were fully biased towards the β-arrestin2 pathway and exhibited partial agonistic activity.

Recently, we developed a series of JNJ 7777120 analogues with subtle chemical switches to optimize their affinity for the hH4R (Engelhardt et al., 2012). This set of compounds is extremely useful to systematically investigate molecular features responsible for biased hH4R signalling. In this study, we therefore determined the intrinsic activity of 48 indolecarboxamides in β-arrestin2 recruitment and Gαi signalling, followed by a detailed structure–activity analysis. We were able to identify molecular features that are positively or negatively correlated with the ability of ligands to induce biased hH4R signalling. The current study is one of the first to use computational analysis (Sirci et al., ; Wijtmans et al., 2012) to correlate ligand structures with intrinsic activities. Moreover, with a hH4R homology model, we could identify receptor regions important for biased hH4R signalling. This is a promising first step towards the identification of ligand efficacy hotspots that may allow the rational design of ligands with specific GPCR (biased) activity and that will aid the understanding of GPCR activation.

Methods

Materials

Cell culture media used for the HEK293T and U2OS-H4R cells were purchased from PAA (Pasching, Austria) and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) respectively. Forskolin and histamine were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Synthesis of the indolecarboxamide analogues was previously described (Engelhardt et al., 2012).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 IU·mL−1 penicillin and 50 μg·mL−1 streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Two million cells were seeded per 10 cm dish 1 day prior to transfection. Approximately four million cells were transfected with 5 μg of cDNA using the polyethyleneimine (PEI) method. Briefly, 2.5 μg hH4R cDNA was supplemented with 2.5 μg CRE-luc plasmid to a total of 5 μg cDNA and mixed with 20 μg of 25 kDa linear PEI in 500 μL of 150 mM NaCl. This transfection mix was incubated at 22°C for 10–30 min and subsequently added drop-wise to a 10 cm dish containing 6 mL of fresh culture medium. PathHunter™ U2OS β-arrestin2 : EA cells stably expressing the human histamine H4 receptor (U2OS-H4R) (Rosethorne and Charlton, 2011) were cultured in minimum essential media (MEM) containing l-glutamine supplemented with FBS (10% v/v), penicillin (100 IU·mL−1), streptomycin (100 μg·mL−1) G418 Geneticin (500 μg·mL−1) and hygromycin (250 μg·mL−1) at 37°C, 5% CO2. On the day prior to the β-arrestin2 recruitment assay, 10 000 cells per well were seeded in a white, clear bottomed 384 well ViewPlate (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, See Green, Buckinghamshire, UK) in 20 μL MEM supplemented as described previously and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

CRE (cyclic AMP response element) luciferase reporter gene assay

Transiently transfected HEK293T cells were stimulated for 6 h with indicated indolecarboxamides or DMSO (1%) in serum-free DMEM containing 1 μM forskolin at 37°C, 5% CO2. Subsequently, the medium was aspirated and 25 μL of luciferase assay reagent [LAR, 0.83 mM ATP, 0.83 mM d-luciferine, 18.7 mM MgCl2, 0.78 μM Na2HPO4, 38.9 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 0.39% glycerol, 0.03% Triton X-100 and 2.6 μM DTT] was added to each well.

Luminescence (1 s per well) was measured in a Victor3 1420 multi-label reader (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences) after 30 min of incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2.

β-Arrestin2 recruitment assay

U2OS-H4R cells were stimulated with increasing amounts of indolecarboxamides or DMSO (1%) for 2 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 in assay buffer (HBSS supplemented with 20 mM HEPES and 0.1% BSA). Directly after stimulation, 25 μL Flash detection reagent (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA, USA) was added and cells were further incubated for 15 min at 22°C on a table shaker. Luminescence was measured on a Lead Seeker imaging system (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Data analysis and statistical procedures

All data were analysed with GraphPad Prism v5 software. Functional concentration–response curves were fitted to a three-parameter response model. Intrinsic activity was determined from the fitted graph top values and normalized for agonists to the full histamine response (100%) or for inverse agonists to the thioperamide response (−100%). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) between intrinsic activities of subseries of compounds were determined using one-way anova, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Fingerprints for Ligands and Proteins three-dimensional quantitative structure–activity relationship (FLAP 3D-QSAR) model building

The dataset used for FLAP 3D-QSAR modelling contained 48 indolecarboxamides with intrinsic activity values ranging from 13 to 100% β-arrestin2 recruitment towards the hH4R. 3D compound structures were generated from SMILES strings using Sybyl-X v.1.3 (Sybyl-X, http://www.tripos.com, Tripos International, St. Louis, MO, USA) with a maximum energy threshold of 20 kcal·mol−1. Protonated forms for each molecule at pH 7.4 were generated using an internal tool integrated in FLAP (Baroni et al., 2007), based on the MoKa algorithm (Milletti et al., 2007). Stereoisomeric forms were considered for chiral compounds 44, 53, 65 and 73. Subsequently, a FLAP database was instructed to generate a maximum of 50 conformers with RMSD value between two conformers of 0.3 Å and an energy window of 20 kcal·mol−1 maximum. Molecular interaction fields (MIFs) were derived from interaction energies with the ligands at specific grid points, as determined by the H (shape), DRY (hydrophobic), N1 (H-bond acceptor) and O (H-bond donor) probes defined in the GRID force field (Goodford, 1985) with a grid spatial resolution of 0.75 Å. Partial least square analysis was used to correlate the MIFs with the intrinsic activities of the different indolecarboxamides. One latent variable (LV1) was set up for the QSAR study as additional components did not lead to either fitting (R2) or predictivity (Q2) improvement (data not shown). This means that only one LV was capable of extracting all the information contained in the GRID-MIF descriptors.

Construction of a hH4R homology model

The hH4R model was built in homology to the hH1R crystal structure (Shimamura et al., 2011) and the binding pose of compound 1 was described previously (Schultes et al., ). We used the pose of compound 1 as initial binding mode for the other ligands, which were rebuilt using MOE version 2011.10 [Chemical Computing Group (CCG) MOE (Molecular Operating Environment), 2011.10 http://www.chemcomp.com/software.htm]. The models were then subjected to energy minimization using the MMFF94x force field with fixed position of the protein backbone atoms.

Results

Evaluation of indolecarboxamides in a cAMP reporter gene assay

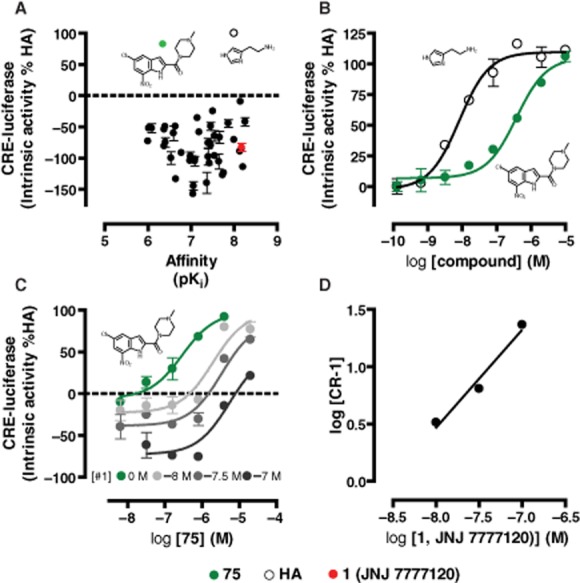

Forty-eight indolecarboxamides (i.e. JNJ 7777120 analogues; see Supporting Information Table S1) and the endogenous agonist histamine were screened (n = 2) for their ability to modulate forskolin-induced Gαi-dependent CRE activity in hH4R-expressing cells (Figure 1A). One indolecarboxamide (compound 75) surprisingly showed positive intrinsic activity of 82 ± 4% compared with full agonist histamine (Eff. 100%). All other compounds including 1 (JNJ 7777120) (Eff. −83 ± 6%) were (weak) inverse agonists (Figure 1A). Full concentration–response curves (n = 3) were performed for compound 75 and histamine (Figure 1B). Compound 75 was identified as full agonist (105 ± 5%) with a potency value (pEC50 = 6.4 ± 0.1) that equals its affinity (pKi = 6.4 ± 0.1) (Engelhardt et al., 2012), but is lower than histamine (pEC50 = 8.1 ± 0.1) (Figure 1B). To confirm that the observed full agonism of 75 is indeed mediated by the hH4R, we added increasing concentrations of 1 (JNJ 7777120) to concentration–response curves of 75. JNJ 7777120 progressively shifted the curves of compound 75 to the right and lowered the basal hH4R signalling, as can be expected from an inverse agonist (Figure 1C). Schild analysis (slope = 0.9 ± 0.1) showed that 75 and 1 (JNJ 7777120) interact with hH4R in a competitive manner (Figure 1D). Moreover, the pA2 (8.5) of 1 (JNJ 7777120) closely resembled its pKi (8.3) for the hH4R (Engelhardt et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

Intrinsic activities of indolecarboxamides in a hH4R-mediated CRE-luciferase reporter gene assay. hH4R-mediated inhibition of 1 μM forskolin-stimulated CRE activity in HEK293T cells. HEK293T-hH4R cells were stimulated with indolecarboxamides (Supporting Information Table S1) (A, 10 μM; B indicated amounts). Intrinsic activity is plotted as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. (A) Affinity versus intrinsic activity plot. Structures of agonists are plotted. (B) Concentration–response curves of HA and compound 75. (C) Concentration–response curves of compound 75 in the absence and presence of increasing amounts of 1 (JNJ 7777120) used to calculate concentration ratios for Schild plot shown in (D). Data shown are pooled data from at least two experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SD (n = 2) or SEM (n = 3) values.

Activity of indolecarboxamides in a β-arrestin2 recruitment assay

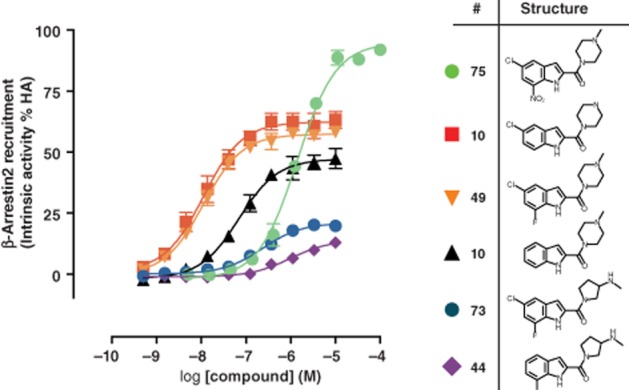

All indolecarboxamides were able to recruit β-arrestin2 to hH4R. Within our dataset, we could identify compounds with a wide range of potencies (pEC50 = 5.3 ± 0.1–8.3 ± 0.1) and intrinsic activities (Eff. = 13 ± 3%–95 ± 4%). Compound 75, identified above as the only indolecarboxamide that exhibited agonism towards CRE activity, displayed the highest intrinsic activity in recruiting β-arrestin2 to hH4R (75, Eff. = 95 ± 4%). Compound 44 is one of the less effective compounds of the indolecarboxamide series (44, Eff. = 14 ± 3%). Substituents at specific positions (R4–R7) on the aromatic ring showed diverse effects on the intrinsic activity of the compounds (75 vs. 1 vs. 10), whereas changes in the basic moiety (i.e. methylpiperazine) significantly reduced the intrinsic activity (49 vs. 73) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Indolecarboxamides exhibit a wide range of intrinsic activities in inducing β-arrestin2 recruitment. U2OS-H4R cells were stimulated with increasing amounts of indicated compounds. Intrinsic activity is plotted as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values.

JNJ 7777120 (1) contains a chlorine atom at position R5, which yields an intrinsic activity for β-arrestin recruitment of 62 ± 4%. If this chlorine is replaced with a nitro group (28), the resulting intrinsic efficacy (62 ± 4%) is not significantly changed compared with JNJ 7777120 (1), whereas moving the nitro group to position R4 is not favoured (21, Eff.39 ± 4%) (Figure 3). Interestingly, moving the nitro group to R7, in combination with the chlorine of JNJ 7777120 (1) at R5, results in a switch to full agonism in both the Gαi (105 ± 5%) and the β-arrestin (95 ± 4%) pathways (Figure 1A).

Figure 3.

Effect of nitro substituent on β-arrestin2 intrinsic activity. U2OS-H4R cells were stimulated with indicated amount of indolecarboxamides to evaluate the effect of NO2 substituents at different positions. Intrinsic activity is plotted as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values.

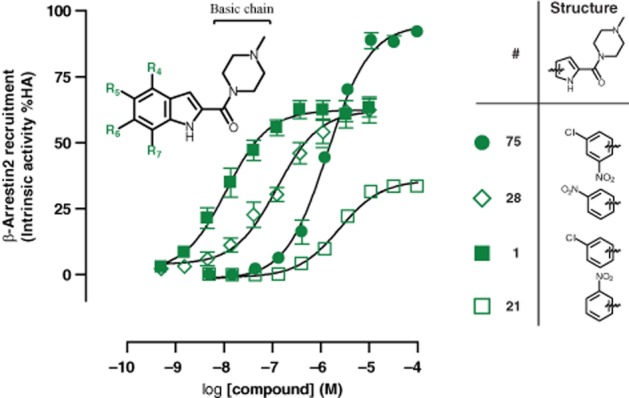

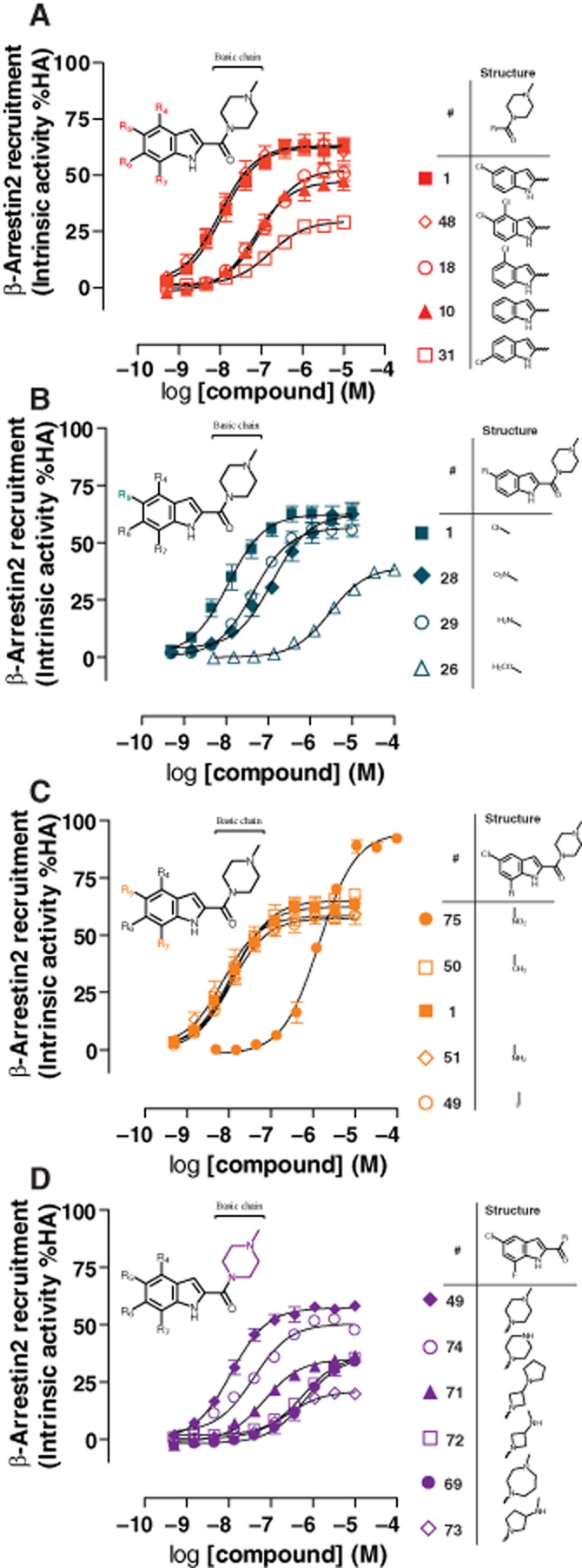

Identification of structural features important for potency and intrinsic activity of indolecarboxamides

The indolecarboxamide dataset allows for a detailed investigation of the structural features that are correlated with intrinsic activity to recruit β-arrestin2 to the hH4R. First, we compared different positions (R4, R5 and R6) of the chlorine atom on the aromatic ring of the indolecarboxamides to the compound without aromatic ring substituents. Addition of a chlorine atom at position R5 is the most favourable in terms of intrinsic activity (1, Eff. = 62 ± 4%), whereas a chlorine substituent at position R4 (18, Eff. = 53 ± 1%) was comparable to the unsubstituted aromatic ring (10, Eff. = 47 ± 4%). Although R4 is not the optimal position for the chlorine atom, it does not appear to interfere with the chlorine at R5, with the doubly (R4, R5) substituted compound 48 (Eff. = 63 ± 4.5%) having comparable intrinsic activity to JNJ 7777120 (1). However, addition of a chlorine atom at position R6 results in a significant decrease in efficacy (31, Eff. = 30 ± 1%) (Figure 4A). The chlorine atom at position R5 displayed the highest potency (1, pEC50 = 8.0 ± 0.1) and the chlorine at position R6 the lowest potency (31, pEC50 = 6.8 ± 0.1) in this subseries.

Figure 4.

Structural features of indolecarboxamides influence compound intrinsic activity in β-arrestin2 recruitment. U2OS-H4R cells were stimulated with indicated amount of indolecarboxamides. (A) Chlorine substituent at different positions. (B) Different substituents at R5 position. (C) Different substituents at R7 position. (D) Effect of different basic side chains. Intrinsic activity is plotted as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values.

Next, different substituents were evaluated at position R5. A chlorine atom (1, Eff. = 62 ± 4%) or a nitro group (28, Eff. = 62 ± 4%) showed the highest intrinsic activity and an amine group (29, Eff. = 57 ± 3%) was also tolerated. Larger substituents at position R5, such as a methoxy group, were less favourable and showed a significant loss in intrinsic activity (26, Eff. = 44 ± 6%) and moreover a 400-fold decrease in potency compared to 1 (Figure 4B). In addition, potency values for 28 (pEC50 = 7.0 ± 0.0) and 29 (pEC50 = 7.4 ± 0.1) decreased more than fourfold compared to 1 (pEC50 = 8.0 ± 0.1).

We have previously demonstrated (Figure 3) that addition of a nitro group into R7 results in a significant increase in intrinsic activity compared to the unsubstituted compound JNJ 7777120 (1). When we further explored this position, we found that substituting this nitro group with either methyl (50, Eff. = 63 ± 4%), amine (51, Eff. = 58 ± 4%) or a fluor atom (49, Eff. = 57 ± 2%), resulted in activity comparable to JNJ 7777120 (1), demonstrating that there is very steep SAR at this position and only the nitro group is able to increase intrinsic activity. Interestingly, although the nitro group resulted in higher intrinsic efficacy, this was coupled with a loss in potency (75, pEC50 = 6.0 ± 0.1) compared to the other compounds in this subseries (pEC50 = 7.8–8.2).

Finally, we evaluated the effect of different basic side chain structures on the intrinsic activity of indolecarboxamides to recruit β-arrestin2. Compound 49 has a methylpiperazine side chain and demonstrated highest intrinsic activity in this subseries (Eff. = 57 ± 2%). Replacement of this methylpiperazine with a piperazine ring (74) had very little effect on intrinsic activity (Eff. = 50 ± 0%), whereas substitutions with azetidin-3-yl pyrrolidine (71, Eff. = 35 ± 1%), 3-aminomethyl azetidine (72, Eff. = 37 ± 3%), 4-methyl-1,4-diazepane (69, Eff. = 36 ± 2%) or 3-aminomethyl pyrrolidine (73, Eff. = 19 ± 5%), all resulted in a significant decrease in intrinsic activity (Figure 4D). The methylpiperazine side chain (1, pEC50 = 8.0 ± 0.1) also resulted in the highest potency. Compound 71 has a 10-fold higher potency (71, pEC50 = 7.2 ± 0.1) than 72 and 69 (72, pEC50 = 6.2 ± 0.1 and 69, pEC50 = 6.2 ± 0.1) to induce β-arrestin2 recruitment to hH4R. In addition, when other substituents were present on the aromatic ring (55, 63, 46), changes in the basic side chain resulted in similar intrinsic activity decreases (Supporting Information Figure S1), indicating an important role for this basic side chain of hH4R ligands to induce β-arrestin2 signalling.

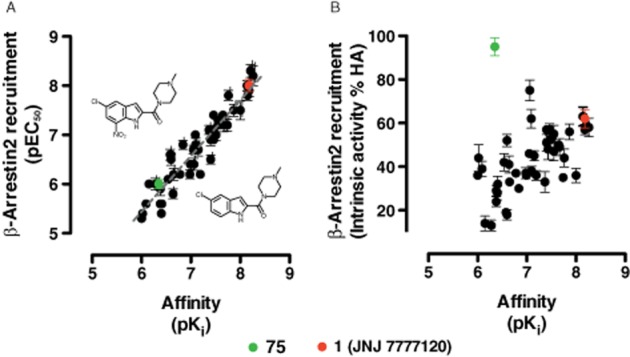

Potency values of all tested indolecarboxamides to stimulate β-arrestin2 recruitment to hH4R are linearly correlated with their hH4R binding affinity values that we previously reported (Engelhardt et al., 2012) (slope = 1.1 ± 0.1, R2 = 0.89) (Figure 5A). In contrast, no correlation was observed between intrinsic activity and affinity values (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Correlation plots between affinity, potency and intrinsic activity in a β-arrestin2 recruitment assay. (A) Linear correlation between affinity and β-arrestin2 recruitment assay potency values. Linear regression line is shown as grey dotted line. (B) No correlation was found between affinity and intrinsic activity in a β-arrestin2 recruitment assay. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values. HA, histamine.

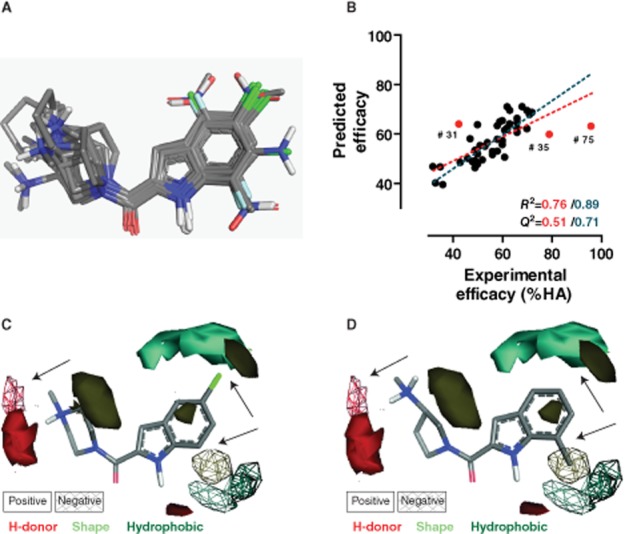

Unravelling ligand interaction regions by FLAP-3D-QSAR

The dataset presented in Figures 4 were analysed using FLAP 3D-QSAR computational-based analysis (Baroni et al., 2007). Four-point pharmacophores (quadruplets) derived from MIFs (Goodford, 1985) were used to align JNJ 7777120 and its analogues 2–77 for the construction of a FLAP 3D-QSAR model (Figure 6A). MIF hotspots derived from this analysis revealed essential molecular interaction features that are either favourable or unfavourable for the intrinsic activity of indolecarboxamides to recruit β-arrestin2 to the hH4R. The correlation plot of experimental versus predicted intrinsic activity values (R2 = 0.76; Q2 = 0.51) showed three outliers (i.e. 31, 35 and 75) (Figure 6B, red dots). These outliers can be explained by the very low variability of the SAR space on position R6 (31 and 35), while for compound 75, the cause probably lies in the large efficacy gap between 75 and the remaining dataset compounds, as well as the fact that this compound is the only unbiased compound of the series. The three outliers were therefore excluded from the analysis and a new intrinsic activity model was computed (Figure 6B, blue dotted lines) that displayed a better fit and higher predictive performance (R2 = 0.89; Q2 = 0.71). 3D pictures of compounds 1 and 44 that display high (Eff. = 62 ± 4%; Figure 6C) and low (Eff. = 14 ± 3%; Figure 6D) intrinsic activity, respectively, were constructed to illustrate the intrinsic activity hotspots by defining positive and negative ligand features (surfaces). The longer basic side chain of 44 places the hydrogen bond donor in a suboptimal position (Figure 6D). Substituents at the R4 and R5 position (1) are positively correlated (shape) with intrinsic activity. Hydrophobic substituents are favourable at position R5 (Figure 6C). However, substituents at position R7 (44) are unfavourable (shape and hydrophobic) for activity (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

FLAP QSAR analysis of the indolecarboxamides intrinsic activity in β-arrestin2 recruitment. (A) Alignment of the 48 tested indolecarboxamides based on molecular interaction fields. (B) Correlation plot between experimental and predicted intrinsic activity values. Regression lines were fitted in the presence (red) or absence (blue) of outliers (see text for details). (C, D) FLAP 3D-QSAR models with high intrinsic activity compound 1 (C) or low intrinsic activity compound 44 (D). Shown surfaces represent positive (solid) or negative (grating) effects of shape, H-bond donor or hydrophobic ligand features. Arrows indicate the most remarkable differences between (C) and (D). HA, histamine.

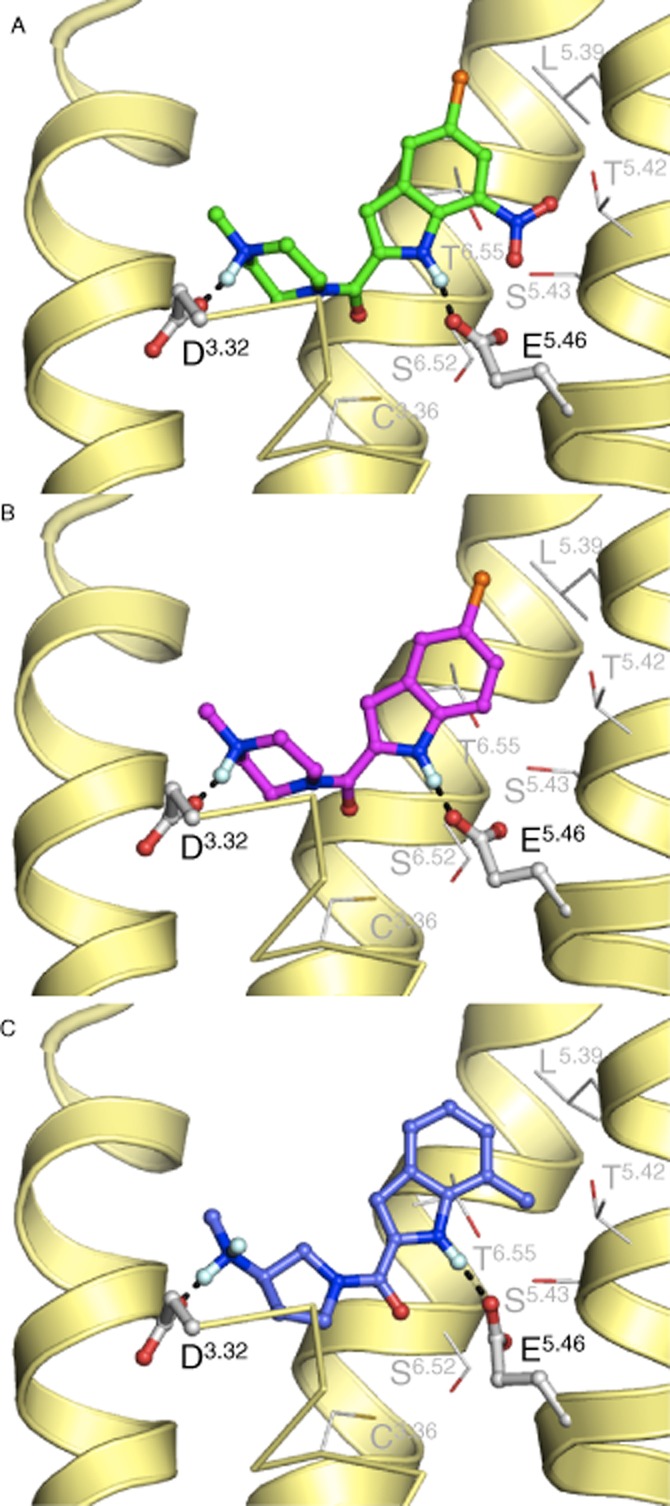

Indolecarboxamide binding in the hH4R binding pocket

We constructed hH4R models with unbiased compound 75 (Figure 7A), high biased β-arrestin2 activity compound 1 (Figure 7B) and low biased β-arrestin2 activity compound 44 (Figure 7C) in order to translate the identified ligand intrinsic activity features to molecular interactions with the hH4R binding pocket. We observed a clear interaction of the basic nitrogen of the methylpiperazine (1 and 75) and 3-aminomethyl pyrrolidine (44) with D3.32 in TM3, which is a key for histamine and JNJ 7777120 binding, as determined in previous studies (Shin et al., 2002; Jongejan et al., 2008). In addition, an interaction between the indole nitrogen with E5.46 in TM5 is most likely to occur and consequently points the aromatic ring towards the hydrophobic cavity at the extracellular side of the hH4R (Jongejan et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2010; Istyastono et al., 2011; Schultes et al., ). The nitro group of compound 75 seems to be directed towards TM5 and the chlorine atom is pointing slightly more upwards towards the extracellular side as compared to 1 (JNJ 7777120). The distance from the positively charged nitrogen in the pyrrolidine to the indole nitrogen (compound 44) is longer than for the respective methylpiperazine derivatives (e.g. 1), which resulted in a different positioning of the aromatic ring. Due to the hydrophobic methyl group at position R7, the aromatic ring is pointed more upwards and less in proximity to TM5 than the nitro substituent of compound 75 at this position (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Three indolecarboxamides fitted in the hH4R binding pocket. (A) Compound 75, (B) compound 1 (JNJ 7777120) and (C) compound 44. Compounds are depicted as ball-and-sticks. Important pocket residues are shown as lines, whereas D3.32 and E5.46 that both form H-bonds with the ligands are also shown as ball-and-sticks. H-bonds between the ligand and pocket residues are represented as black dotted lines. The backbone TM helices 5, 6 and 7 (right to left) are presented as yellow helices. For clarity, helix 3 is partly presented by yellow ribbons.

Discussion and conclusion

Despite the recent progress in GPCR structural biology and the current availability of both inactive and active GPCR structures (Palczewski et al., 2000; Jaakola et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008; Warne et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2010; Rosenbaum et al., 2011; Shimamura et al., 2011; Manglik et al., 2012), it is still challenging to successfully predict ligand interaction points and efficacy switches. The recent evidence for multiple active GPCR states (Kahsai et al., 2011; Kenakin, 2011) has added additional complexity and the molecular understanding of ligand-biased GPCR activation can be considered as one of the challenges in the field. Previously, we identified several biased ligands for the hH4R (Rosethorne and Charlton, 2011; Nijmeijer et al., 2012). Although this biased activity seemed to be spread among different ligand classes, all five investigated indolecarboxamides showed a full bias toward β-arrestin2 recruitment. In this study, we tested 48 indolecarboxamides with subtle structural differences in aromatic ring substituents and in the basic side chain (Engelhardt et al., 2012). The 47 β-arrestin2-biased indolecarboxamides displayed a wide variation in potencies and intrinsic activities. The potencies correlated with previously published affinities (Engelhardt et al., 2012), which is in line with earlier observations that β-arrestin2 signalling is correlated with receptor occupancy and in line with the 1:1 stoichiometry of receptor and β-arrestin2 interaction in an enzyme fragment-based complementation assay (Granier et al., 2012; Kruse et al., 2012; Riddy et al., 2012; Shoichet and Kobilka, 2012). No correlation was observed between affinity and intrinsic activities, making it worthwhile to identify the structural requirements for intrinsic activity.

In a Gαi protein-dependent reporter gene assay, compound 75 was the only compound that displayed agonism. Intriguingly, this compound exhibited also the highest intrinsic activity in the β-arrestin2 recruitment assay and is therefore classified as an unbiased ligand. Interestingly, the polar nitro group at position R7 did not match with the negative H (shape) MIF coefficient in the constructed β-arrestin2-biased ligand intrinsic activity model. This could be explained by the fact that compound 75 is the only unbiased indolecarboxamide of this series and we hypothesize that 75 recruits β-arrestin2 to hH4R by potentially stabilizing a distinct receptor conformation as compared with the other indolecarboxamides.

Using the binding mode of indolecarboxamides in the hH4R that was previously proposed and validated with site-directed mutagenesis data (Jongejan et al., 2008; Schultes et al., ) as well as with the recently successfully applied FLAP method [hH3R, CXCR7 and calcium channel compounds (Ioan et al., 2012; Sirci et al., ; Wijtmans et al., 2012)] for 3D-QSAR, we now identified receptor regions important for ligand efficacy. In the histamine H3R, it was previously shown that the length between the charged groups in the ligand is important for intrinsic activity (Govoni et al., 2006). Because of the crucial interaction between D3.32 and the basic nitrogen in the side chain of the indolecarboxamides, the position of the aromatic ring depends on the distance between this basic nitrogen and the indole nitrogen. Besides the length, also the different substitutions at the aromatic ring are responsible for this ring placement in the binding pocket. The nitro group at position R7 of unbiased indolecarboxamide 75 seems able to form hydrogen bonds with threonine and serine residues in transmembrane (TM) 5, which is possibly a crucial step in hH4R Gαi activation. Notably, these polar interactions cannot take place for 1 and 44. Interestingly, compound 51 that has an amine group at R7 does not show agonism in the Gαi pathway, which could indicate that the polar interactions are made via a hydrogen bond-accepting group in the ligand.

There are multiple theories for GPCR activation mechanisms and most of them focus on the rearrangement of TM helices such as 5, 6 and 7 in combination with aromatic side chain rotamer switches (Ballesteros et al., 2000; Schwartz et al., 2013). The efficacy of dopamine D1 agonists for cAMP stimulation has been correlated with ligand interactions with a series in TM5 (Chemel et al., 2012). For the β2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2), interaction with D3.32 and an inward shift of TM5 was required for agonist activity as demonstrated by strong polar interactions between ligand and residues in TM5 (Strader et al., 1989; Liapakis et al., 2000; Rasmussen et al., 2011a; Zocher et al., 2012) as well as an interaction between S5.43 and N6.55 (Katritch et al., 2009; Vilar et al., 2011). Interestingly, these polar interactions with TM5 could be confirmed in the recent crystal structure models (Rosenbaum et al., 2011). In contrast, no TM5 movement was observed in the A2AAR, indicating that TM5 interactions are not a general phenomenon (Katritch and Abagyan, 2010). We recently suggested that agonist binding results in hH1R activation via S3.36, a rotamer toggle switch that initiates activation via N7.45 resulting in conformational changes in helices 6 and 7 (Jongejan et al., 2005). In addition, agonist binding disrupts the T3.37 interaction with TM5, which resulted in a P5.50-induced unwinding of the TM5 helix around the side chain I3.40 (Sansuk et al., 2011). Shortly after the discovery of the hH4R, D3.32 and E5.46 were identified as key residues for ligand binding and activation (Shin et al., 2002). The residues T5.42 and S5.43 in TM5 of hH4R were not significantly involved in histamine binding or activation, but N4.57 and S6.52 played a role in receptor activation (Shin et al., 2002). More recently, N4.57 was shown to play a role in the binding of clobenpropit analogue VUF5228 (Istyastono et al., 2011) and was identified as the key determinant for ligand binding to H4R orthologs through its influence on the orientation of E5.46 (Lim et al., 2010). In addition, mutation of this N4.57 residue as well as S5.43 decreased the affinity of JNJ 7777120. The possible interaction of 75 with polar hH4R receptor residues is currently under investigation.

Based on our dataset, we observed that β-arrestin2 activation of the tested indolecarboxamides is less dependent on such polar interactions than Gαi protein signalling. In a previous quantitative structure–affinity relationship study, the position R7 tolerated both lipophilic and polar moieties (Engelhardt et al., 2012). Yet, in the present study, we show that (hydrophobic) substituents at this position are less favourable for biased β-arrestin2 recruitment. This illustrates that there are specific intrinsic activity hotspots that do not correspond with high affinity features. Substitutions (i.e. halogens or hydrophobic groups) on positions R6 or R7 seem to repulse the ligand from the TM5 region in the hH4R homology model, resulting in a lower intrinsic activity. Furthermore, the replacement of methylpiperazine with other basic side chains was found to be detrimental for intrinsic activity. With our FLAP 3D-QSAR model, we could identify an exact hotspot, namely the correct positioning of the H-bond donor MIF generated by the positively charged nitrogen in the basic side chain, which interacts with D3.32 in the H4R homology model. Consequently, variations in the basic side chain resulted in a slightly different orientation of the aromatic ring. Based on the hH4R homology model, we observed that the less effective compounds seem to point their aromatic ring more upwards to the extracellular side of hH4R and less towards the TM5 region, hence probably resulting in decreased β-arrestin2 recruitment.

In this study, we have identified ligand and receptor features responsible for biased hH4R signalling by testing 48 indolecarboxamides with subtle structural differences. We discovered an unbiased indolecarboxamide (75) that is a full agonist in both Gαi protein and β-arrestin2 signalling. All other compounds displayed a full bias toward β-arrestin2 recruitment. An extensive analysis of the ligand structures and corresponding intrinsic activity via a FLAP 3D-QSAR model revealed β-arrestin2-biased activity hotspots, which were subsequently projected in a hH4R homology model to identify receptor regions that play a role in biased signalling. Importantly, while a hydrogen bond acceptor that points towards the TM5 region is crucial for Gαi-protein signalling, this polar interaction is not necessary to induce β-arrestin2 recruitment by fully biased ligands. In the latter case, intrinsic activity is probably dependent on subtle changes in orientation of the aromatic ring in the hydrophobic sub-pocket. Identification of molecular features that are essential for (biased) ligands is important to predict compound intrinsic activity and allows the rational design of biased and unbiased hH4R ligands.

Acknowledgments

S. N., H. F. V., C. d. G. and R. L. participate in the European COST Action BM0806. C.d. G. is supported by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO: VENI Grant 700.59.408. We thank Molecular Discovery Ltd. for granting FLAP suite licence.

Glossary

- CRE

cyclic AMP response element

- FLAP

Fingerprints for Ligands and Proteins

- hH4R

human histamine H4 receptor

- MIF

molecular interaction fields

- TM

transmembrane

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Effect of different basic side chains influences compound intrinsic activity in β-arrestin2 recruitment. U2OS-H4R cells were stimulated with indicated amount of indolecarboxamides. (A) R5-Cl, R7-CH3 (B) R7-F (C) R7-CH3. Intrinsic activity is plotted as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values.

Table S1 Overview of potency and intrinsic activity values in a β-arrestin2 recruitment and CRE-luciferase assay. Intrinsic activity is calculated as percentage of maximal histamine (HA) response. Data shown are pooled data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars indicate SEM values.

References

- Ballesteros JA, Deupi X, Olivella M, Haaksma EEJ, Pardo L. Serine and threonine residues bend alpha-helices in the chi(1) = g(-) conformation. Biophys J. 2000;79:2754–2760. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroni M, Cruciani G, Sciabola S, Perruccio F, Mason JS. A common reference framework for analyzing/comparing proteins and ligands. Fingerprints for Ligands and Proteins (FLAP): theory and application. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:279–294. doi: 10.1021/ci600253e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, McDonald PH. Seeking ligand bias: assessing GPCR coupling to beta-arrestins for drug discovery. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2010;7:e37–e42. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemel BR, Bonner LA, Watts VJ, Nichols DE. Ligand specific roles for transmembrane 5 serine residues in the binding and efficacy of dopamine D (1) receptor catachol agonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:729–738. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.077339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coge F, Guenin SP, Rique H, Boutin JA, Galizzi JP. Structure and expression of the human histamine H4-receptor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:301–309. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire SM, Violin JD. Biased ligands for better cardiovascular drugs: dissecting G-protein-coupled receptor pharmacology. Circ Res. 2011;109:205–216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt H, de Esch IJ, Kuhn D, Smits RA, Zuiderveld OP, Dobler J, et al. Detailed structure-activity relationship of indolecarboxamides as H4 receptor ligands. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;54:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galandrin S, Oligny-Longpre G, Bouvier M. The evasive nature of drug efficacy: implications for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodford PJ. A computational procedure for determining energetically favorable binding sites on biologically important macromolecules. J Med Chem. 1985;28:849–857. doi: 10.1021/jm00145a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govoni M, Lim HD, El-Atmioui D, Menge WM, Timmerman H, Bakker RA, et al. A chemical switch for the modulation of the functional activity of higher homologues of histamine on the human histamine H3 receptor: effect of various substitutions at the primary amino function. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2549–2557. doi: 10.1021/jm0504353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, et al. Structure of the δ-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature. 2012;485:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K, Kruse AC, Asada H, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Shiroishi M, Zhang C, et al. Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature. 2012;482:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioan P, Ciogli A, Sirci F, Budriesi R, Cosimelli B, Pierini M, et al. Absolute configuration and biological profile of two thiazinooxadiazol-3-ones with L-type calcium channel activity: a study of the structural effects. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:8994–9003. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25946j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istyastono EP, Nijmeijer S, Lim HD, van de Stolpe A, Roumen L, Kooistra AJ, et al. Molecular determinants of ligand binding modes in the histamine H(4) receptor: linking ligand-based three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models to in silico guided receptor mutagenesis studies. J Med Chem. 2011;54:8136–8147. doi: 10.1021/jm201042n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EY, Lane JR, et al. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan A, Bruysters M, Ballesteros JA, Haaksma E, Bakker RA, Pardo L, et al. Linking agonist binding to histamine H1 receptor activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:98–103. doi: 10.1038/nchembio714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan A, Lim HD, Smits RA, de Esch IJ, Haaksma E, Leurs R. Delineation of agonist binding to the human histamine H4 receptor using mutational analysis, homology modeling, and ab initio calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:1455–1463. doi: 10.1021/ci700474a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahsai AW, Xiao K, Rajagopal S, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Sun J, et al. Multiple ligand-specific conformations of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:692–700. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritch V, Abagyan R. GPCR agonist binding revealed by modeling and cristallography. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;32:637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritch V, Reynolds KA, Cherezov V, Hanson MA, Roth CB, Yeager M, et al. Analysis of full and partial agonists binding to beta2 adrenergic receptor suggests a role of transmembrane helix V in agonist-specific conformational changes. J Mol Recognit. 2009;22:307–318. doi: 10.1002/jmr.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Ligand-selective receptor conformations revisited: the promise and the problem. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:346–354. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:296–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse AC, Hu J, Pan AC, Arlow DH, Rosenbaum DM, Rosemond E, et al. Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 2012;482:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs R, Chazot PL, Shenton FC, Lim HD, de Esch IJ. Molecular and biochemical pharmacology of the histamine H4 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liapakis G, Ballesteros JA, Papachristou S, Chan WC, Chen X, Javitch JA. The forgotten serine. A critical role for Ser-203 5.42 in ligand binding to and activation of the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37779–37788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HD, de Graaf C, Jiang W, Sadek P, McGovern PM, Istyastono EP, et al. Molecular determinants of ligand binding to H4R species variants. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:734–743. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Ma X, Jiang X, Wilson SJ, Hofstra CL, Blevitt J, et al. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of a fourth histamine receptor (H(4)) expressed in bone marrow. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:420–426. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, et al. Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milletti F, Storchi L, Sforna G, Cruciani G. New and original pKa prediction method using grid molecular interaction fields. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:2172–2181. doi: 10.1021/ci700018y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse KL, Behan J, Laz TM, West RE, Jr, Greenfeder SA, Anthes JC, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel human histamine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:1058–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Itadani H, Hidaka Y, Ohta M, Tanaka K. Molecular cloning and characterization of a new human histamine receptor, HH4R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:615–620. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer S, Vischer HF, Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ, Leurs R. Analysis of multiple histamine H4 receptor compound classes uncovers Gαi and β-arrestin2-biased ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:1174–1182. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Morikawa N, Saito Y, Masuho Y, Matsumoto S. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel type of histamine receptor preferentially expressed in leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36781–36786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Scheerer P, Hofmann KP, Choe HW, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:373–386. doi: 10.1038/nrd3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Fung JJ, Pardon E, Casarosa P, Chae PS, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the β(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011a;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, DeVree BT, Zou Y, Kruse AC, Chung KY, Kobilka TS, et al. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011b;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lefkowitz RJ. Molecular mechanism of β-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:179–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddy DM, Stamp C, Sykes DA, Charlton SJ, Dowling MR. Reassessment of the pharmacology of Sphingosine-1-phosphate S1P3 receptor ligands using the DiscoveRx PathHunter™ and Ca2+ release functional assays. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:868–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DM, Zhang C, Lyons JA, Holl R, Aragao D, Arlow DH, et al. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β(2) adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ. Agonist-biased signaling at the histamine H4 receptor: JNJ7777120 recruits β-arrestin without activating G proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:749–757. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansuk K, Deupi X, Torrecillas IR, Jongejan A, Nijmeijer S, Bakker RA, et al. A structural insight into the reorientation of transmembrane domains 3 and 5 during family A G protein-coupled receptor activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:262–269. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes S, Nijmeijer S, Engelhardt H, Kooistra AJ, Vischer HF, de Esch IJP, et al. Mapping histamine H4 receptor–ligand binding modes. MedChemComm. 2013;4:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz TW, Frimurer TM, Holst B, Rosenkilde MM, Elling CE. Molecular mechanism of 7TM receptor activation – a global toggle switch model. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:481–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura T, Shiroishi M, Weyand S, Tsujimoto H, Winter G, Katritch V, et al. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature. 2011;475:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N, Coates E, Murgolo NJ, Morse KL, Bayne M, Strader CD, et al. Molecular modeling and site-specific mutagenesis of the histamine-binding site of the histamine H4 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:38–47. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoichet BK, Kobilka BK. Structure-based drug screening for G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirci F, Istyastono EP, Vischer HF, Kooistra AJ, Nijmeijer S, Kuijer M, et al. Virtual fragment screening: discovery of histamine H(3) receptor ligands using ligand-based and protein-based molecular fingerprints. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:3308–3324. doi: 10.1021/ci3004094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader CD, Sigal JS, Dixon RA. Structural basis of beta adrenergic receptor function. FASEB J. 1989;3:1825–1832. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.7.2541037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurmond RL, Desai PJ, Dunford PJ, Fung-Leung WP, Hofstra CL, Jiang W, et al. A potent and selective histamine H4 receptor antagonist with anti-inflammatory properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:404–413. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar S, Karpiak J, Berk B, Costanzi S. In silico analysis of the binding of agonists and blockers to the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J Mol Graph Model. 2011;29:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, et al. Selectively engaging β-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:572–579. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, Moukhametzianov R, Edwards PC, Henderson R, et al. Structure of a beta1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijtmans M, Maussang D, Sirci F, Scholten DJ, Canals M, Mujic-Delic A, et al. Synthesis, modeling and functional activity of substituted styrene-amides as small-molecule CXCR7 agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;51:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Chien EY, Mol CD, Fenalti G, Liu W, Katritch V, et al. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science. 2010;330:1077–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampeli E, Tiligada E. The role of histamine H4 receptor in immune and inflammatory disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Michalovich D, Wu H, Tan KB, Dytko GM, Mannan IJ, et al. Cloning, expression, and pharmacological characterization of a novel human histamine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:434–441. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocher M, Fung JJ, Kobilka BK, Muller DJ. Ligand-specific interactions modulate kinetic, energetic, and mechanical properties of the human β2 adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2012;20:1391–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.