Abstract

Background and Purpose

Schizophrenia is a highly debilitating disorder characterized by hallucinations and delusions, but also impaired cognition such as memory. While hallucinations and delusions are the main target for pharmacological treatment, cognitive impairments are rarely treated. Evidence exists that histamine has a role in the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, which could be the basis of the development of a histamine-type treatment. Histamine H3 antagonists have been shown to improve memory performance in experimental animals, but these effects have been little investigated in humans within the context of impaired cognition in schizophrenia and using sensitive measures of brain activity. In the present study, the effects of betahistine (H3 antagonist/H1 agonist) on learning and memory, and associated brain activity were assessed.

Experimental Approach

Sixteen healthy volunteers (eight female) aged between 18 and 50 years received two p.o. doses of betahistine (48 mg) or placebo separated by 30 min, on separate days according to a two-way, double-blind, crossover design. Volunteers performed an N-back working memory task and a spatial paired associates learning task while being scanned using a MRI scanner.

Key Results

Task-related activity changes in well-defined networks and performance were observed. No betahistine-induced changes in brain activity were found in these networks. Alternatively, liberal whole-brain analyses showed activity changes in areas outside task networks, like the lateral geniculate nucleus.

Conclusions and Implications

Clear effects of betahistine on working memory could not be established. Future studies should use higher doses and explore the role of histamine in visual information processing.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed issue on Histamine Pharmacology Update. To view the other articles in this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2013.170.issue-1

Keywords: H3 antagonist, H1 agonist, betahistine, learning, memory, histamine, human cognition, imaging, MRI

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a highly debilitating disorder and has a lifetime prevalence of up to 0.66% affecting many people worldwide. Its characteristic positive and negative symptoms include delusions/hallucinations and anhedonia, which largely prevent normal everyday functioning and have been the focus of pharmacological treatment in the past (for review, see, van Os and Kapur, 2009). In addition, patients with schizophrenia suffer from impaired cognitive function, which is characterized by deficits in attention, memory and executive functioning. These cognitive impairments in schizophrenia are now gaining increasing attention as a target for treatment (Keefe and Fenton, 2007).

The main current theory describing neural deficits in schizophrenia was proposed over 30 years ago and postulates that altered activity in two dopamine pathways in the brain explain both the positive and cognitive symptoms (Meltzer and Stahl, 1976; Davis et al., 1991). Increased striatal dopaminergic activity is associated with positive symptoms such as hallucinations (Keshavan et al., 2008; Kegeles et al., 2010). Decreased activity in the mesocortical dopamine pathway is associated with decreased functioning of the frontal cortex (Keshavan et al., 2008; Abi-Dargham et al., 2012) and associated cognitive deficits, which include impaired episodic memory, working memory and executive functioning (Abi-Dargham et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2007; Pae et al., 2008).

Current pharmacological treatments are mainly based on this dopamine hypothesis. Antipsychotics block the dopamine D2 receptor whereby dopaminergic activity at this receptor is decreased, which effectively reduces the positive symptoms. However, the action of existing antipsychotics does not alleviate the cognitive symptoms (Meltzer et al., 1999; Marder, 2006), despite atypical drugs increasing prefrontal dopamine release (Kuroki et al., 1999; Westerink et al., 2001). Cognitive improvements and clinical changes appear to be unrelated (Harvey et al., 2006), suggesting that cognitive deficits are a separate target for drug treatment. Therefore, other transmitter systems should be explored to improve the understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying schizophrenia symptomatology with an emphasis on cognitive functions.

There is evidence that the histamine neurotransmitter system is involved in schizophrenia (for reviews, Ito, 2004; Vohora and Bhowmik, 2012), possibly analogous to the dopamine system with hyper-functional neurotransmission (Prell et al., 1995; Arrang, 2007; Keshavan et al., 2008) and hypo-functional prefrontal neurotransmission possibly underlying cognitive deficits. Evidence for histaminergic hypo-functionality comes from the studies of Nakai et al. (1991) and Iwabuchi et al. (2005), who found decreased densities of histamine H1 receptors. Also, Jin et al. (2009) demonstrated an increase in H3 receptor binding specifically in the frontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. When activated, the histamine H1 receptor has excitatory properties and the H3 receptor has inhibitory properties. Taken together, these results suggest that the typical cognitive impairments observed in schizophrenia patients could be as a result of neuronal histaminergic hypo-functionality specifically in the frontal cortex. Increasing frontal histaminergic activity may, therefore, help to alleviate the cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia. As the effects of H3 antagonism/inverse agonism may be restricted to cognition, the present study focused on testing the effects of increasing histamine transmission on prefrontal cortical functioning.

During the past 10 years, the histamine H3 receptor has been studied extensively in animals for its potential to improve cognitive functioning. Blocking the H3 receptor using H3 antagonists has been shown to increase histamine neurotransmission (Schwartz et al., 1991) and improve cognitive functions in a variety of animal models (Esbenshade et al., 2008). More specifically, in an animal model of schizophrenia-related symptoms, H3 antagonists have been found to improve cognitive performance on tasks measuring memory and executive functions (Ligneau et al., 2007; Mahmood et al., 2012; for review, see Esbenshade et al., 2008). Many H3 inverse agonists/antagonists are in clinical test trial, but unfortunately, are not freely available to establish the promising cognitive enhancing effects in humans. However, betahistine may be useful in this respect, the effects of which will be assessed in the present study.

Betahistine is a drug that has been used for over 40 years to treat Meniere's disease and acts as a H3 antagonist/H1 agonist. Betahistine enters the CNS where it increases histamine neurotransmission (Tighilet et al., 2002; 2005), and where it may be able to enhance cognitive functioning. Betahistine's effects on psychomotor performance have been assessed in several studies. However, these studies found no change in performance after p.o. doses ranging from 48 mg to three times 72 mg (Betts et al., 1991; Gordon et al., 2003; Banqui et al., 2008; Szabadi et al., 2009).

In contrast, Vermeeren et al. (2006) did find a small, but significant increase in electrophysiological measures of arousal during a vigilance task after a single dose of betahistine of 64 mg suggesting (i) the presence and effects of betahistine in the brain, and (ii) that brain activity may be more sensitive to drug-induced changes than behaviour. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to determine if the administration of betahistine leads to a change in performance on tasks of functions known to be impaired in schizophrenia and their associated brain activity as measured using functional MRI (fMRI) in healthy volunteers.

Interestingly, Vermeeren et al. (2006) observed their effects between 1 and 2 h after drug administration, but observed the strongest effects between 3 and 4 h after administration. In contrast, in a previous study in which the pharmacokinetics of betahistine were assessed, a very short tmax (±30 min) was observed (Obecure, Clinical Study Report, Cinca, 2010). The relatively long-lasting effects and delayed peak effects after administration observed by Vermeeren et al. (2006) may be explained by the fact that betahistine's metabolites also show affinity for the H3 receptor (Fossati et al., 2001), possibly causing the delayed effects. However, as the main focus of the present paper was on betahistine's effects and not its metabolites, we chose to assess the effects directly after dosing in accordance with the pharmacokinetic data.

In the present study, it was hypothesized that betahistine increases histamine neurotransmission and performance on tasks depending on frontal lobe activity, which is typically impaired in schizophrenia. To test this hypothesis, healthy volunteers were recruited to perform working memory and associative learning tasks, while their brain activity was measured using fMRI, after they had received two doses of betahistine or placebo, each dose separated by 30 min. Betahistine did not induce any changes in performance or brain activity in the task-related areas.

Methods

Volunteers

Sixteen healthy right-handed volunteers were recruited (eight females; mean age ± SEM: 24.5 ± 1.0 years) by the institution's email ‘circulars’. Honey et al. (1999), who also used a similar task to the one used in the present study, observed effects of antipsychotics with only 10 subjects per group. Since the effects of betahistine are expected to be small, we recruited sixteen volunteers. Inclusion criteria were a good physical and mental health, including a BMI between 18 and 30 kg·m−2, total weight between 50 and 100 kg, blood pressure between 60–90 mmHg diastolic and 100–150 mmHg systolic and QTc interval <450 ms as demonstrated with a 12-lead electrocardiogram. Exclusion criteria were presence or history of clinically significant haematological, renal, endocrine, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hepatic, psychiatric or neurological diseases/disorders. This included volunteers with a history of epilepsy or seizures and more than one febrile convulsion or glaucoma.

Volunteers using prescription or non-prescription drugs (except paracetamol or acetaminophen at <1 g·day−1, and p.o. contraceptives for female volunteers), within 7 days or 5 half-lives (whichever was longest) before the first dose of trial medication, were excluded. Volunteers with a history of regular alcohol consumption exceeding 28 drinks week−1 within 6 months of screening were also excluded, (one drink equals 5 ounces (±150 mL) of wine or 12 ounces (±360 mL) of beer or 1.5 ounces (±45 mL) of hard liquor). Further exclusion criteria were use of tobacco- or nicotine-containing products in excess of the equivalent of five cigarettes per day, fulfilment of any MRI contra-indications such as a history of surgery involving metal implants, history of claustrophobia or inability to tolerate the mock-scanner environment during the habituation/screening session.

The study was approved by the South-East London Regional Ethics Committee (ref. nr.: 10/H0807/82) and conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments (Seoul, Korea, 2008; World Medical Association, 1964).

Study design and treatments

Volunteers received two doses of betahistine 48 mg, p.o. [for single dose: tmax = ± 30 min, Cmax = ± 1.26 μg·mL−1 (Obecure, Clinical Study Report, Cinca, 2010)], separated by 30 min and placebo on separate days according to a two-way double-blind crossover design. Treatment days were separated by a washout period of at least 1 week to exclude any carry-over effects. Treatment order was randomized and counterbalanced.

Procedure

Volunteers visited the test facility on three occasions. First, volunteers were screened and trained to perform the tasks. On treatment days, participants were instructed to have a light breakfast at least 2 h before arrival. A urine drug screen and a breath alcohol test were performed to test for other drugs that might interfere with study measurements. Participant's medical history was reviewed and a brief physical examination was performed by a medical doctor to confirm suitability including measurements of cardiovascular system, respiratory systems, supine and standing blood pressure and pulse rate.

One hour after arrival participants received a dose of betahistine 48 mg or placebo p.o.. Participants always took their p.o. medication with 150 mL tap water, and in the presence of a responsible medical doctor and a research nurse and/or investigator. After the participants indicated they had swallowed the capsules, the inside of their mouth was checked to ensure that the capsules have been swallowed. The participants were then immediately positioned in the MR scanner where clinical and structural scans were performed. Thirty minutes after the first dose, volunteers received another dose of 48 mg betahistine or placebo p.o.. After the second dose, the participants performed an N-back working memory task and a visuospatial paired associates learning (PAL) task, which assesses spatial learning. Thereafter, the brief physical examination was repeated to ensure volunteers were fit to be transported home.

Tasks

Working memory

The N-back task is a stimulus detection task with a working memory component that is parametrically varied by memory load. This version of the N-back task is modified from our previous version, which reliably activates frontal and parietal regions of the brain (Caceres et al., 2009). Volunteers were required to monitor a series of letters sequentially presented in the centre of a computer screen, and to respond by pressing the right button on a two-button box as fast as possible with their dominant (right) hand whenever a letter was presented that was the same as the letter presented one, two or three trials previously (i.e. 1-back, 2-back and 3-back respectively). In the fourth (control) condition, volunteers had to press the button as fast as possible whenever they detected the target letter (e.g. X; 0-back). In all other cases, volunteers pressed the left button. The relevant condition (i.e. N-back) was indicated at the beginning of each block of trials. Letters were presented 21 times per block for 1000 ms at a rate of 1 per 3000 ms including 3 or 4 targets, totalling 11 targets per N-back level. Volunteers completed blocks of 0-, 1-, 2- or 3-back trials repeated three times in pseudorandom order. Percentage and speed of correct responses and associated brain activity were recorded per N-back level. Total duration of the task was approximately 6 min.

Learning

The PAL task requires learning of stimulus-location associations and is based on the version of CANTAB (http://www.cantab.com). Initially, six distinct patterns appeared on the screen, one by one in a pseudorandom order. Each pattern appeared in a different location and remained there for 1000 ms. After the last pattern was revealed, the six patterns were shown one by one in the centre of the screen for 4000 ms. Volunteers respond to each stimulus by moving the joystick towards the position they believe to be the original location. This cycle was presented twice more with the same stimuli in the same locations but shown in a different order, giving volunteers three opportunities (named first, second and third learning block) per stimulus set to learn stimulus-location associations. Overall, the task consisted of six unique sets of stimuli to be learned. The control condition involved viewing a single (previously learned) stimulus appearing in each location followed by the same stimulus appearing in the centre of the screen accompanied by a grey rectangle highlighting the location to which the joystick should be moved. The control condition was also presented six times, controlling for the visual and motor requirements within the same framework as the learning conditions. The total task length was 12 min and 12 s. The number of correct responses, reaction time and brain activity were recorded.

Image acquisition

Volunteers were scanned using a 1.5T GE Signa scanner (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) located at the Maudsley Hospital, London, using an eight-channel head coil for radio frequency transmission and reception. High-resolution gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) volume was acquired to assist with image registration: 43 slices, time of repetition (TR) = 3000 ms and time of echo (TE) = 40 ms. Slices consisted of 1 mm3 voxels in a 128 × 128 matrix with a 0.3 mm gap between the slices. The functional data for N-back and PAL tasks were collected using an EPI sequence consisting of TR = 2000 ms and TE = 40 ms with 29 slices per volume acquired sequentially, collected with 0.75 mm gap between slices and a voxel size of 3 mm3 in a 64 × 64 matrix. During scanning, volunteers were asked to lie as still as possible.

Image processing

The functional data were analysed using the Statistical and Parametric Mapping suite (SPM8: http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Time series were initially corrected for slice time acquisition and head movements were corrected by realigning images to the mean image. In order to minimize the effect of excessive movement, a threshold value was used of one voxel (3.75 mm) for translational movement and one voxel on the edge of the brain for rotational movement (2.53 degrees), beyond which participants were excluded if such movements occurred on three occasions in one run. No volunteers showed any excessive head movements. Functional data were co-registered with anatomical data from the first session. All data were transformed to a standardized space [Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template] and spatially smoothed using a Gaussian filter with an 8 × 8 × 8 mm full-width half maximum.

Statistical analyses and models

For N-Back task, performance data (correct responses and reaction time) were analysed using a 2 × 4 factorial general linear model (GLM) with Treatment (two levels: betahistine, placebo) and Memory load (four levels: 0, 1, 2 and 3 back) as factors. Main effects and interactions were further explored using specific contrast, with P ≤ 0.05 as significance level. All behavioural data were analysed using SPSS 18 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

For the first-level analysis of the functional data, 11 regressors were defined: 0-, 1-, 2- and 3-back, task instructions and six movement parameters (three rotational, three translational). Thereafter, beta values were estimated and three contrasts of interest were derived by contrasting 1-, 2- and 3-back with 0-back to be used in a second-level analysis testing for Treatment effects and Treatment by N-back level interactions.

Performance data from PAL (correct responses and reaction time) were analysed using GLM for repeated measures with Treatment (two levels: betahistine, placebo) and Block (three levels: first, second and third) as within-subjects factors. One participant performed very poorly on all trials and the data were therefore excluded from the analysis.

Functional data during encoding and recall were separately analysed. For the first-level analysis, 14 regressors were defined: Control-, first, second and third block of task performance and corresponding task instructions. Additionally, six movement parameters (three rotational, three translational) were modelled. Thereafter, beta values were estimated and three contrasts of interest were derived by contrasting activity during the first, second and third block with the control block.

For all functional data, second-level analysis was performed to determine significant effects of task conditions and Treatment, and their interactions. Therefore, a flexible factorial anova was set up with subject as random factor, and Treatment and N-back (for N-back) or Block (for PAL) as within-subject factors. To determine task networks, two analyses were performed. First, masks were derived (P ≤ 0.001 cluster-forming threshold and P ≤ 0.05 cluster threshold) to be used to test for drug effects within task networks based on activity data obtained from an independent sample of eleven healthy volunteers. Second, activity during the placebo session of the volunteers included in the drug study was also analysed to assist interpretation of any findings (because these maps were used in a qualitative manner and to minimize type II errors we used a cluster-forming threshold of P ≤ 0.001 and included clusters of ≥20 voxels). Three t-contrasts (0-back ≤ 1-back, 0-back ≤ 1-back, 0-back ≤ 3-back) were used to determine activity in regions involved in N-back performance, as strategy might change with N-back, networks used might differ and activity needs to be considered per N-back level. For the PAL task, two F-contrasts (main effect of Block during encoding and recall) for performance in the placebo condition were used to keep the number of comparisons relatively low as the each PAL condition consisted of six blocks. An analysis was performed using N-back masks (for 1- 2- and 3-back networks separately) and PAL masks (for encoding and recall separately) to ascertain main treatment effects or Treatment by N-back/Block interactions within the respective networks. We used a P < 0.001 voxelwise, cluster-forming threshold with multiple comparisons correction at cluster level of P < 0.05 [family wise error (FWE)-corrected]. Given the novelty, and therefore, exploratory nature of this study, we also report large clusters with a minimal cluster size of 20 voxels at an uncorrected level of P < 0.001 based on a whole-brain analysis.

Results

Behavioural data

N-back

With increased memory load, reaction time increased (F3,13 = 8.6, P < 0.002) and the number correctly identified targets decreased (F3,13 = 12.6, P < 0.001). Reaction time was longer and fewer targets were identified for 2-back compared to 1-back (F1,15 = 7.7, P < 0.016 and F1,15 = 7.1, P < 0.017, respectively) and for 3-back compared to 2-back (F1,15 = 14.8, P < 0.002 and F1,15 = 10.3, P < 0.006 respectively). There were no significant effects of betahistine on N-back performance. Table 1 shows the means ± SEM and details on main task and drug effects and their interaction.

Table 1.

Effects of treatments on N-back and PAL performance

| Mean ± SEM | Main effect Task | Main effect treatment | Interaction treatment × task | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task measure | Placebo | Betahistine | F | d.f. | P | F | d.f. | P | F | d.f. | P |

| N-back (rt) | 8.6 | 3,13 | 0.002 | <1 | 1,15 | n.s. | <1 | 3,13 | n.s. | ||

| 0-back | 565 ± 26 | 555 ± 28 | |||||||||

| 1-back | 542 ± 23 | 547 ± 29 | |||||||||

| 2-back | 594 ± 36 | 578 ± 32 | |||||||||

| 3-back | 647 ± 42 | 621 ± 34 | |||||||||

| N-back (num. cor.) | 12.6 | 3,13 | <0.001 | <1 | 1,15 | n.s. | <1 | 3,13 | n.s. | ||

| 0-back | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | |||||||||

| 1-back | 8.8 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | |||||||||

| 2-back | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.2 | |||||||||

| 3-back | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | |||||||||

| PAL (rt) | 61.4 | 2,13 | <0.001 | <1 | 1,14 | n.s. | <1 | 2,13 | n.s. | ||

| First block | 1054 ± 37 | 1028 ± 31 | |||||||||

| Second block | 952 ± 36 | 938 ± 22 | |||||||||

| Third block | 878 ± 29 | 875 ± 21 | |||||||||

| PAL (num. cor.) | 72.1 | 2,13 | <0.001 | <1 | 1,14 | n.s. | <1 | 2,13 | n.s. | ||

| First block | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | |||||||||

| Second block | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |||||||||

| Third block | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | |||||||||

Mean ± SEM of reaction time and number of correct responses per task condition and drug treatment. Main effects of task condition and drug treatment, and their interaction for N-back performance and PAL performance are displayed. Significant (P < 0.05) main effects are displayed in boldface.

Paired associates learning

With increased blocks of encoding, reaction time decreased (F2,13 = 61.4, P < 0.001) and number of correctly identified target locations increased (F2,13 = 72.1, P < 0.001) during recall. Reaction time was shorter and number of correctly indicated locations was higher for the second block of recall compared to the first (F1,14 = 18.7, P < 0.001 and F1,14 = 31.1, P < 0.001, respectively), and for the third compared to the second (F1,14 = 47.1, P < 0.001 and F1,14 = 3.8, P < 0.001 respectively). There were no significant effects of betahistine on PAL performance. Table 1 shows the mean ± SEM values and details of the main task and drug effects and their interaction.

Imaging data

N-back

After placebo, the 1-back condition did not induce significantly more or significantly less activity compared to the 0-back condition in areas previously found involved in 1-back processing. In contrast, significantly increased activity during 2-back compared to 0-back was observed in the right superior parietal cortex [Brodmann area (BA7); t = 5.28, P ≤ 0.001], left inferior parietal cortex (BA40; t = 4.13, P ≤ 0.001), right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA45; t = 4.09, P ≤ 0.001) and right middle frontal cortex (BA6; t = 3.87, P ≤ 0.001). Decreased activity was observed in the left precuneus (BA30; t = 6.89, P ≤ 0.001), right middle cingulate (BA23: t = 6.06, P ≤ 0.001), left fusiform gyrus (BA37; t = 5.92, P ≤ 0.001), left superior occipital cortex (BA39; t = 5.82, P ≤ 0.001), left superior frontal gyrus (BA9; t = 5.60, P ≤ 0.001), left inferior temporal gyrus (BA20; t = 4.22, P ≤ 0.001) and right inferior parietal cortex (BA48; t = 3.79, P ≤ 0.001). Activity in the 3-back network showed a similar pattern. Activity increases during 3-back compared to 0-back were observed in right superior parietal cortex (BA7; t = 6.17, P ≤ 0.001), left inferior parietal cortex (BA40; t = 5.41, P ≤ 0.0001), right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA45; t = 4.07, P ≤ 0.001) and left and right medial frontal cortex (BA6; t = 3.68, P ≤ 0.001). Decreases were observed in the left precuneus (BA30; t = 6.71, P ≤ 0.001) and left medial orbitofrontal cortex (BA10; t = 5.30, P ≤ 001) See Table 2 for details.

Table 2.

Associates learning performance: effects of N-back and PAL on brain activity

| Brain area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates (MNI) | |||||||

| Name | BA | X | Y | Z | Cluster size (voxels) | F/t-value (peak) | P-value (peak) |

| N-back | |||||||

| 1-back | (t-value) | ||||||

| – | |||||||

| 2-back | 0-back < 2-back | ||||||

| Right superior parietal cortex | 7 | 30 | −60 | 46 | 489 | 5.28 | <0.001 |

| Left inferior parietal cortex | 40 | −34 | −50 | 44 | 619 | 4.13 | <0.001 |

| Right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 45 | 48 | 40 | 30 | 166 | 4.09 | <0.001 |

| Right middle frontal cortex | 6 | 36 | 2 | 62 | 327 | 3.87 | <0.001 |

| 2-back < 0-back | |||||||

| Left precuneus | 30 | −8 | −54 | 10 | 1946 | 6.89 | <0.001 |

| Right middle cingulum | 23 | 2 | −20 | 40 | 218 | 6.06 | <0.001 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | 37 | −28 | −40 | −14 | 110 | 5.92 | <0.001 |

| Left superior occipital cortex | 39 | −42 | −74 | 32 | 448 | 5.82 | <0.001 |

| Left superior frontal gyrus | 9 | −12 | 48 | 38 | 1857 | 5.60 | <0.001 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | 20 | −46 | 10 | −38 | 148 | 4.22 | <0.001 |

| Right inferior parietal cortex | 48 | 54 | −28 | 24 | 44 | 3.79 | <0.001 |

| 3-back | 0-back < 3-back | ||||||

| Right superior parietal cortex | 7 | 32 | −70 | 52 | 548 | 6.17 | <0.001 |

| Left inferior parietal cortex | 40 | −40 | −50 | 44 | 429 | 5.41 | <0.001 |

| Right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | 45 | 44 | 38 | 32 | 193 | 4.07 | <0.001 |

| Left/right medial frontal cortex | 6 | 6 | 12 | 54 | 246 | 3.68 | <0.001 |

| 3-back < 0-back | |||||||

| Left precuneus | 30 | −8 | −56 | 14 | 383 | 6.71 | <0.001 |

| Left medial orbitofrontal cortex | 10 | −4 | 52 | −6 | 292 | 5.30 | <0.001 |

| PAL | (F-value) | ||||||

| PAL-encoding | Block (decrease) | ||||||

| Right middle occipital cortex | 19 | 32 | −90 | −4 | 59 | 16.99 | <0.001 |

| Left middle occipital cortex | 19 | −32 | −88 | −4 | 380 | 16.96 | <0.001 |

| Right inferior occipital cortex | 37 | 38 | −64 | −8 | 45 | 9.86 | <0.001 |

| Block (increase) | |||||||

| Right angular gyrus | 39 | 56 | −66 | 28 | 32 | 9.51 | <0.001 |

| Left precuneus | 7 | 0 | −66 | 44 | 48 | 9.01 | <0.001 |

| PAL-recall | Block (decrease) | ||||||

| – | |||||||

| Block (increase) | |||||||

| Left middle cingulum | 23 | 0 | −16 | 38 | 119 | 14.20 | <0.001 |

| Left posterior cingulum | 23 | −2 | −52 | 22 | 106 | 13.78 | <0.001 |

| Left medial orbital frontal cortex | 10 | −2 | 56 | −2 | 93 | 12.55 | <0.001 |

Brain areas showing N-back-, PAL-encoding- and PAL-recall-related changes in activation are indicated by their BA, peak voxel coordinates in MNI space and cluster size. Main effects of N-back or block are indicated by their F-value and FWE-corrected P-value.

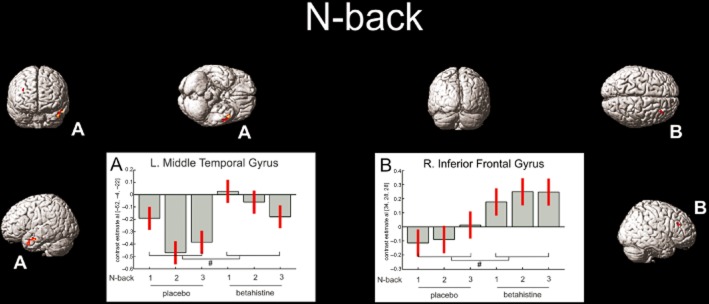

Masks from an independent cohort were used to test for drug-placebo differences within 1-back, 2-back and 3-back networks. No significant main effects of treatment were observed. However, in a whole-brain analysis and at an uncorrected level, a betahistine-induced increase in activation was observed in 34 voxels in the right triangular inferior frontal gyrus (BA48; F = 16.17, P ≤ 0.001). In addition, less deactivation in a cluster of 95 voxels in the left middle temporal gyrus (BA21; F = 16.48, P < 0.001) was observed. However, for both areas, further t-contrasts did not reveal any differences in specific N-back conditions. Please see Table 3 for details and Figure 1 for a graphical representation.

Table 3.

Betahistine-induced changes in brain activity during N-back and PAL task performance

| Brain area | Treatment effects | Treatment × task interaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates (MNI) | |||||||||

| Name | BA | X | Y | Z | Cluster size (voxels) | F-value (peak) | P-value (peak) | F-value (peak) | P-value (peak) |

| N-back (1-back) | BET versus PLC (1-back) | ||||||||

| – | |||||||||

| N-back (2-back) | BET versus PLC (2-back) | ||||||||

| – | |||||||||

| N-back (3-back) | BET versus PLC (3-back) | ||||||||

| – | |||||||||

| N-back (outside N-back networks) | BET versus PLC | ||||||||

| Left middle temporal cortex | 21 | −52 | −4 | −22 | 95 | 16.48 | <0.001 | – | – |

| Right inferior frontal cortex | 48 | 34 | 28 | 28 | 34 | 16.17 | <0.001 | – | – |

| PAL (encoding) | BET versus PLC (encoding) | ||||||||

| – | |||||||||

| PAL (outside PAL networks) | |||||||||

| R. middle cingulum | 23 | −6 | −26 | 44 | 88 | 19.34 | <0.001 | – | – |

| L. lateral geniculate nucleus | – | −20 | −14 | −10 | 53 | 19.98 | <0.001 | – | – |

| R. lateral geniculate nucleus | – | 20 | −8 | −6 | 39 | 18.47 | <0.001 | – | – |

| L. posterior cingulum (subcortical) | – | −12 | −38 | 16 | 28 | 14.79 | <0.001 | – | – |

| R. parietal cortex (subcortical) | – | 26 | −46 | 30 | 20 | 16.61 | <0.001 | – | – |

| PAL (recall) | BET versus PLC (recall) | ||||||||

| – | |||||||||

| PAL (outside PAL networks) | |||||||||

| R. precentral gyrus | 6 | 26 | −20 | 62 | 26 | 18.09 | <0.001 | – | – |

| R. thalamus | – | −8 | −22 | 14 | 96 | – | – | 9.17 | <0.001 |

Brain areas showing effects of betahistine on changes in brain activation inside and outside areas related to N-back, PAL-encoding and PAL-recall performance are indicated by their BA, peak voxel coordinates in MNI space and cluster size. Main effects of treatment or treatment by task level (i.e. N-back difficulty) or task block (PAL learning block) are indicated by their peak F-value and voxel P-value.

Figure 1.

Coloured areas indicate the main effects of betahistine at a P < 0.001 uncorrected significance level per voxel and indicated by #. Betahistine induced less deactivation in the left middle temporal cortex and relative activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus.

Paired associates learning

Encoding

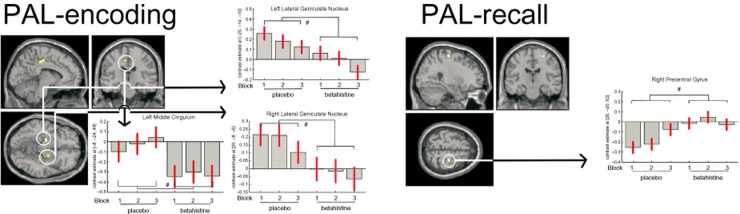

During placebo, activity in the left and right middle occipital cortex decreased with learning block (BA19; F = 16.96, P ≤ 0.001 and F = 16.99, P ≤ 0.001 for left and right respectively). In addition, activity change in 45 voxels in the right inferior occipital gyrus (BA37) exceeded the significance threshold (F = 9.86, P ≤ 0.001). In the left and right middle occipital cortex activity was lower after the second presentation compared to the first (t = 4.05, P < 0.001 and t = 4.74, P ≤ 0.001 respectively). Activity was also lower for the third presentation compared to the second, but failed to reach significance. An activity increase over encoding blocks was observed in the right angular gyrus (BA39; F = 9.51, P ≤ 0.001) and left precuneus (BA7; F = 9.01, P ≤ 0.001) in which there was less deactivation during block 2 compared to block 1 (right angular gyrus; t = 3.69, P ≤ 0.001 and left precuneus; t = 4.23, P ≤ 0.001). See Table 2 for details. Mask-constrained analysis did not reveal any significant treatment-induced changes using the FWE-corrected significance threshold. However, at an uncorrected level, activity was decreased after betahistine administration in a cluster of 88 voxels in the left middle cingulate (BA23; F = 19.34, P < 0.001). Using t-contrasts in each learning block separately showed that during the third block of encoding only was there a significant reduction in activity with betahistine (t = 4.47, P ≤ 0.001). Bilateral lateral geniculate nuclei (LGN) also showed decreased bold response after betahistine administration (F = 19.98, P < 0.001 and F = 18.47, P < 0.001, for left and right respectively). Again, separate t-contrasts showed that the difference only reached significance in the third blocks of encoding (t = 4.04, P ≤ 0.001). After betahistine administration, a cluster of 28 voxels near the left posterior cingulate (F = 14.79, P < 0.001) and a cluster of 20 voxels in the right parietal lobe (F = 16.61, P < 0.001) showed increased activity. For both areas, t-contrasts did not reveal any significant treatment differences in specific blocks. Please see Table 3 for details and Figure 2 for a graphical representation.

Figure 2.

Coloured areas represent betahistine-induced changes in brain activity as indicated by a main treatment effect during encoding (left) and retrieval (right). Significant (P < 0.001 uncorrected) main effects are indicated by #. Activity was decreased in left and right LGN, left middle cingulum during encoding, and a reduced deactivation was observed in the right precentral gyrus during recall.

Recall

Brain activity in the left medial orbital frontal cortex (BA10; F = 12.55, P ≤ 0.001), left middle cingulate (BA23; F = 14.20, P ≤ 0.001), and left posterior cingulate (BA23; F = 13.78, P ≤ 0.001) showed a main effect of learning block. During the second block of picture location recall, deactivation was less as compared to the deactivation during the first block in the left and right medial orbital frontal cortex (t = 4.11, P < 0.001), the left and right middle cingulate (t = 5.09, P ≤ 0.001) and in the left and right precuneus/posterior cingulate (t = 4.63, P < 0.001 and t = 3.99, P ≤ 0.001). A further decrease in deactivation from the second to the third block was observed in left and right anterior cingulate medial frontal cortex and right precuneus/posterior cingulate but did not reach significance. See Table 2 for details.

Mask-constrained analysis did not show significant drug-induced changes. However, at an uncorrected level, one cluster of 26 voxels in the right precentral gyrus was less deactivated compared to placebo (BA6, F = 18.09, P < 0.001). This difference was significant during the first (t = 4.32, P ≤ 0.001) and second block of recall (t = 4.86, P ≤ 0.001). An interaction was observed in a cluster of 96 voxels in the right thalamus (F = 9.17, P < 0.001). During placebo, brain activity increased from the first block of recall to the third, while for betahistine, the same increase was not apparent, with the second block showed highest activity, and the comparison between blocks 2 and 3 reached significance (t = 4.68, P ≤ 0.001); see Table 3 for details and Figure 2 for a graphical representation of these data.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore H3 antagonism/H1 agonism as a mechanism to enhance cognition in patients with schizophrenia by assessing brain activity in healthy volunteers. Increased working memory load in N-back task performance induced changes in brain activity in accordance with previous studies (Owen et al., 2005). Activity decreases in visual areas during the encoding phase of PAL with repeating blocks of stimuli was expected as was the change in activity in the posterior, middle and anterior cingulate cortex with repeated recall of stimulus locations (De Rover et al., 2011). While betahistine did not significantly change brain activity in regions defined as task networks, it did modulate brain activity during N-back and PAL performance in a whole-brain analysis and this will be discussed as regards implications for future research directions.

N-back task performance during the placebo resulted in increased activity in a parieto-frontal network and larger deactivation mostly in the posterior, middle and anterior cingulate regions with increased task demands. It has been suggested that increases in activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex are associated with increased organizational strategies (e.g. Bor et al., 2003; 2004). The bilateral posterior parietal cortex has been associated with temporal storage of verbal information (Jonides et al., 1998). However, the right superior and inferior parietal cortex are usually associated with temporary storage of spatial information (Smith and Jonides, 1998), but are also part of an attentional network and often activated during working memory tasks (Owen et al., 2005). Finally, decreases in posterior, middle and anterior cingulate activity are thought to be due to re-allocation of resources from active processes during the resting state to processes involved in tasks at hand (e.g. McKiernan et al., 2003). The present results are in line with what is generally observed with N-back task performance (Owen et al., 2005), which validates our methods.

Similarly, in line with previous results, is the involvement of the occipital cortex in stimulus encoding during PAL performance, and the posterior cingulate/right precuneus (De Rover et al., 2011) and anterior cingulate during recall (McKiernan et al., 2003). However, de Rover et al. (2011) did not observe effects of stimulus repetition as their task was designed to detect effects of encoding, but not changes over blocks. The present findings add to these results, as they showed that activity decreases with repeated presentation of visual spatial material. Additionally, deactivation of the posterior, middle and anterior cingulate has also been proposed to be a consequence of a shift from monitoring external environment (Gould et al., 2006) or internal states (McKiernan et al., 2003) to goal-directed behaviour. As learned material is repeated and recall of that material is easier, fewer resources are needed and this is reflected in less deactivation of the default mode network.

The absence of significant effects of betahistine in brain areas related to memory task performance was unexpected. A potential explanation may be that doses given/plasma levels achieved were insufficient to induce measurable changes in brain activity, especially as betahistine undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism (Chen et al., 2003). The dose we chose to administer was relatively high compared to previous studies and accompanying safety and tolerability data were available. Similar data would be required to justify the use of extremely high doses. To determine a minimum dose at which to expect effects, several previous studies were considered; while a lack of behavioural effects has been observed many times before (e.g. Betts et al., 1991; Gordon et al., 2003), others have observed effects on brain activity (Vermeeren et al., 2006) using an acute 64 mg p.o. dose, which should produce blood-plasma levels somewhat similar to those in the present study. Nevertheless, the effects observed by the latter group were only small and higher dosages may be needed to induce clear measurable effects.

Whole-brain analyses were conducted to explore the effects of betahistine on activity in brain areas outside the defined task networks, which could have implications for the direction of future research. Betahistine did induce changes in some brain areas during task performance, but these did not remain significant when formal multiple comparisons correction was used. Therefore, these results must be interpreted with caution.

During N-back task performance, betahistine induced less deactivation of the left middle temporal gyrus and more activation of the right triangular inferior frontal gyrus. The left middle temporal gyrus has been associated with semantics in language comprehension rather than language elements with little semantics such N-back stimuli (Davis and Gaskell, 2009; Diaz and McCarthy, 2009). Perhaps, semantics in language and N-back task performance share a subprocess affected by betahistine, like echoic memory in a language perception model (Davis and Gaskell, 2009). The right triangular inferior frontal cortex has not been extensively studied. In contrast, the left triangular inferior frontal cortex has been associated with language processing and syntax in particular (Nauchi and Sakai, 2009; Sakai et al., 2009). Alternatively, it may be that temporal lobe regions show reduced activity associated with reduced distractibility during accurate sustained attention performance and this reduction is attenuated by betahistine, possibly making participants more easily distracted, which is a testable hypothesis (Lawrence et al., 2003).

In the recall phase of PAL, betahistine caused less deactivation in the right precentral gyrus as compared to placebo. The precentral gyrus plays an important role in motor programming of a response with the contralateral (i.e. left) hand (e.g. Kawashima et al., 1997). Since all responses were right-handed, the right precentral gyrus would not be expected to play a role in producing a left hand manual response. The ipsilateral right precentral gyrus is deactivated with right-handed responses (Manson et al., 2008), but contradictory findings exist (Wu et al., 2008). Deactivations in the present study were derived from contrasting first, second and third block of recall with the control condition, which resulted in (i) relative deactivation for the recall blocks, that is, greater activity during the control condition, and (ii) a decrease in deactivation over the recall blocks, that is, activity reaches control condition levels. After betahistine administration, the deactivation was largely diminished, which could mean that activity during the control condition was decreased or activity during recall blocks was increased, possibly resulting from an increased preparedness to respond. While this aligns with the faster responses after betahistine, the difference was not significant.

The observed decreased activity in the bilateral LGN during PAL's encoding phase is possibly the most supported finding. The LGN is a relay station between the eyes and primary visual cortex, processing visual information such as colour, spatial, temporal frequency and luminance (Kandel et al., 2000). Dense binding of [125I]-iodoproxyfan, an H3 agonist, has been observed in the dorsal LGN indicating the presence of H3 receptors and supporting the hypothesis that histamine plays a role in visual information processes. Moreover, our previous findings, that H1 antagonism affects visual feature extraction performance represented by delayed electrophysiological activity (Van Ruitenbeek et al., 2009), also supports this notion. In the present study, H3 antagonism also led to a decrease in activity. The mechanism whereby the H3 receptor might be involved in LGN activity, particularly as indicated by the bold response, is not known and should be subjected to further research. Furthermore, the potential role of H3 receptors in the LGN may be functionally selective, in that it may affect vision of colour, luminance, spatial or temporal frequency. Selective involvement in separate functions may be studied by comparing effects of parametrically varied aspects of vision after betahistine administration to those after placebo.

To conclude, both N-back and PAL produced expected patterns of activation and, betahistine administration modulated brain activity, but which was outside task activation networks and at an uncorrected significance level. As the limited effects may be the consequence of poor brain penetration at the doses used, the question of whether the mechanism whereby betahistine exerts its function (H1 agonism/H3 antagonsim) is suitable for treating learning and memory deficits in clinical disorders like schizophrenia remains unresolved. Future studies are needed to explore the effects of a range of higher oral doses to determine the central effects of betahistine, although the importance of studies using more selective compounds should not be discounted. In a more broad view, evidence is now accumulating for a role of histamine in visual information processing. Future studies need to investigate more closely the role of histamine in visual information processing and the consequential changes in cognitive functioning.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-PEOPLE-2009-IEF) under grant agreement n°253127.

The study was supported by a European Union Marie Curie fellowship grant (FP7-PEOPLE-2009-IEF) awarded to P v R. Both P v R and M A M were paid by King's College London for their scientific work.

Glossary

- BA

Brodmann area

- EPI

echo planar imaging

- FWE

family wise error

- GLM

general linear model

- LGN

lateral geniculate nucleus

- MNI

Montreal Neurological Institute

- PAL

paired associates learning

- TE

time of echo

- TR

time of repetition

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Mawlawi O, Lombardo I, Gil R, Martinez D, Huang Y, et al. Prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors and working memory in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3708–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Dargham A, Xu X, Thompson JL, Gil R, Kegeles LS, Urban N, et al. Increased prefrontal cortical D(1) receptors in drug naive patients with schizophrenia: a PET study with [(1)(1)C]NNC112. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:794–805. doi: 10.1177/0269881111409265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM. Histamine and schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:247–287. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banqui Q, Banjar WMA, Gazzaz J, Hou RH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, et al. Comparison of betahistine and diphenhydramine on alertness and automatic functions in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(5 Suppl):A33. [Google Scholar]

- Betts T, Harris D, Gadd E. The effects of two anti-vertigo drugs (betahistine and prochlorperazine) on driving skills. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:455–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor D, Duncan J, Wiseman RJ, Owen AM. Encoding strategies dissociate prefrontal activity from working memory demand. Neuron. 2003;37:361–367. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor D, Cumming N, Scott CE, Owen AM. Prefrontal cortical involvement in verbal encoding strategies. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:3365–3370. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres A, Hall DL, Zelaya FO, Williams SC, Mehta MA. Measuring fMRI reliability with the intra-class correlation coefficient. Neuroimage. 2009;45:758–768. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XY, Zhong DF, Duan JL, Yan BX. LC-MS-MS analysis of 2-pyridylacetic acid, a major metabolite of betahistine: application to a pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers. Xenobiotica. 2003;33:1261–1271. doi: 10.1080/716689336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinca R. Evaluation of safety, drug-drug interactions and pharmacokinetic profiles of co-administration of betahistine with olanzapine in healthy female subjects. Ramat Gan, Israel: OBEcure, Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Kahn RS, Ko G, Davidson M. Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1474–1486. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Gaskell MG. A complementary systems account of word learning: neural and behavioural evidence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:3773–3800. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz MT, McCarthy G. A comparison of brain activity evoked by single content and function words: an fMRI investigation of implicit word processing. Brain Res. 2009;1282:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbenshade TA, Browman KE, Bitner RS, Strakhova M, Cowart MD, Brioni JD. The histamine H3 receptor: an attractive target for the treatment of cognitive disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1166–1181. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Barone D, Benvenuti C. Binding affinity profile of betahistine and its metabolites for central histamine receptors of rodents. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:389–392. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CR, Doweck I, Nachum Z, Gonen A, Spitzer O, Shupak A. Evaluation of betahistine for the prevention of seasickness: effect on vestibular function, psychomotor performance and efficacy at sea. J Vestib Res. 2003;13:103–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Brown RG, Owen AM, Bullmore ET, Howard RJ. Task-induced deactivations during successful paired associates learning: an effect of age but not Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2006;31:818–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Green MF, Bowie C, Loebel A. The dimensions of clinical and cognitive change in schizophrenia: evidence for independence of improvements. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey GD, Bullmore ET, Soni W, Varatheesan M, Williams SC, Sharma T. Differences in frontal cortical activation by a working memory task after substitution of risperidone for typical antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13432–13437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito C. The role of the central histaminergic system on schizophrenia. Drug News Perspect. 2004;17:383–387. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2004.17.6.829029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi K, Ito C, Tashiro M, Kato M, Kano M, Itoh M, et al. Histamine H1 receptors in schizophrenic patients measured by positron emission tomography. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin CY, Anichtchik O, Panula P. Altered histamine H3 receptor radioligand binding in post-mortem brain samples from subjects with psychiatric diseases. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:118–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Schumacher EH, Smith EE, Koeppe RA, Awh E, Reuter-Lorenz PA, et al. The role of parietal cortex in verbal working memory. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5026–5034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05026.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. 4th edn. New-York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima R, Inoue K, Sato K, Fukuda H. Functional asymmetry of cortical motor control in left-handed subjects. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1729–1732. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705060-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Fenton WS. How should DSM-V criteria for schizophrenia include cognitive impairment? Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:912–920. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Frankle WG, Gil R, Cooper TB, Slifstein M, et al. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:231–239. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Tandon R, Boutros NN, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, ‘just the facts’: what we know in 2008 Part 3: neurobiology. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:89–107. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki T, Meltzer HY, Ichikawa J. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on extracellular dopamine levels in rat medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence NS, Ross TJ, Hoffmann R, Garavan H, Stein EA. Multiple neuronal networks mediate sustained attention. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:1028–1038. doi: 10.1162/089892903770007416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligneau X, Landais L, Perrin D, Piriou J, Uguen M, Denis E, et al. Brain histamine and schizophrenia: potential therapeutic applications of H(3)-receptor inverse agonists studied with BF2.649. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan KA, Kaufman JN, Kucera-Thompson J, Binder JR. A parametric manipulation of factors affecting task-induced deactivation in functional neuroimaging. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:394–408. doi: 10.1162/089892903321593117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood D, Khanam R, Pillai KK, Akhtar M. Protective effects of histamine H3-receptor ligands in schizophrenic behaviors in experimental models. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SC, Wegner C, Filippi M, Barkhof F, Beckmann C, Ciccarelli O, et al. Impairment of movement-associated brain deactivation in multiple sclerosis: further evidence for a functional pathology of interhemispheric neuronal inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 2008;187:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1276-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR. Drug initiatives to improve cognitive function. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 9):31–35. discussion 36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Stahl SM. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 1976;2:19–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/2.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Park S, Kessler R. Cognition, schizophrenia, and the atypical antipsychotic drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13591–13593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai T, Kitamura N, Hashimoto T, Kajimoto Y, Nishino N, Mita T, et al. Decreased histamine H1 receptors in the frontal cortex of brains from patients with chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:349–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauchi A, Sakai KL. Greater leftward lateralization of the inferior frontal gyrus in second language learners with higher syntactic abilities. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3625–3635. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, McMillan KM, Laird AR, Bullmore E. N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:46–59. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pae CU, Juh R, Yoo SS, Choi BG, Lim HK, Lee C, et al. Verbal working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: an FMRI investigation. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118:1467–1487. doi: 10.1080/00207450701591131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prell GD, Green JP, Kaufmann CA, Khandelwal JK, Morrishow AM, Kirch DG, et al. Histamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with chronic schizophrenia: their relationships to levels of other aminergic transmitters and ratings of symptoms. Schizophr Res. 1995;14:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rover M, Pironti VA, McCabe JA, Acosta-Cabronero J, Arana FS, Morein-Zamir S, et al. Hippocampal dysfunction in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a functional neuroimaging study of a visuospatial paired associates learning task. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2060–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ruitenbeek P, Vermeeren A, Smulders FT, Sambeth A, Riedel WJ. Histamine H1 receptor blockade predominantly impairs sensory processes in human sensorimotor performance. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai KL, Nauchi A, Tatsuno Y, Hirano K, Muraishi Y, Kimura M, et al. Distinct roles of left inferior frontal regions that explain individual differences in second language acquisition. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2440–2452. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JC, Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Pollard H, Ruat M. Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:1–51. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Jonides J. Neuroimaging analyses of human working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12061–12068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadi E, Banqui Q, Banjar WMA, Gazzaz J, Langley RW, Bradshaw CM. Interactions between modafinil and betahistine on alertness and automatic functions in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6 Suppl):A60. [Google Scholar]

- Tighilet B, Trottier S, Mourre C, Chotard C, Lacour M. Betahistine dihydrochloride interaction with the histaminergic system in the cat: neurochemical and molecular mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;446:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01795-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighilet B, Trottier S, Lacour M. Dose- and duration-dependent effects of betahistine dihydrochloride treatment on histamine turnover in the cat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;523:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeeren A, Ramaekers JG, Vuurman EFPM, Riedel WJ. Effects of histamine-3 receptor antagonsim on electrocortical arousal during vigilance performance in man. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(5 Suppl):A31. [Google Scholar]

- Vohora D, Bhowmik M. Histamine H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists on cognitive and motor processes: relevance to Alzheimer's disease, ADHD, schizophrenia, and drug abuse. Front Syst Neurosci. 2012;6:72. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss EM, Siedentopf C, Golaszewski S, Mottaghy FM, Hofer A, Kremser C, et al. Brain activation patterns during a selective attention test – a functional MRI study in healthy volunteers and unmedicated patients during an acute episode of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BH, Kawahara Y, De Boer P, Geels C, De Vries JB, Wikstrom HV, et al. Antipsychotic drugs classified by their effects on the release of dopamine and noradrenaline in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;412:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. 1964. 2008. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

- Wu X, Chen K, Liu Y, Long Z, Wen X, Jin Z, et al. Ipsilateral brain deactivation specific to the nondominant hand during simple finger movements. Neuroreport. 2008;19:483–486. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f6030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]