Abstract

Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T sp.nov. is the type strain of Senegalemassilia anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov., the type species of a new genus within the Coriobacteriaceae family, Senegalemassilia gen. nov. This strain, whose genome is described here, was isolated from the fecal flora of a healthy Senegalese patient. S. anaerobia is a Gram-positive anaerobic coccobacillus. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence and annotation. The 2,383,131 bp long genome contains 1,932 protein-coding and 58 RNA genes.

Keywords: Senegalemassilia anaerobia, genome

Introduction

Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T (= CSUR P147 = DSMZ 25959) is the type strain of S. anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. This bacterium was isolated from the feces of a healthy Senegalese patient. It is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, indole-negative coccobacillus. Classically, the polyphasic taxonomy is used to classify the prokaryotes by associating phenotypic and genotypic characteristics [1]. Culturomics is a new subfield of genomics aimed at studying the microbial repertoire of the gut, and has already lead to the isolation of many new bacterial species [2]. In parallel, as more than 3,000 bacterial genomes have been sequenced so far, we proposed to integrate genomic data in descriptions of new bacterial species [3-15].

The family Coriobacteriaceae was created in 1997, in the class Actinobacteria, and currently contains 13 genera of anaerobic Gram-positive members of the normal intestinal microbiota from humans and animals [16-28]. Among them, Gordonibacter and Paraeggherthella have occasionally been isolated from Crohn’s disease specimens [26].

Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for S. anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. strain JC110T together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation. These characteristics support the circumscription of the genus Senegalemassilia and the species S. anaerobia.

Classification and features

A stool sample was collected from a healthy 16-year-old male Senegalese volunteer patient living in Dielmo (rural village in the Guinean-Sudanian zone in Senegal), who was included in a research protocol. Written assent was obtained from this individual. No written consent was needed from his guardians for this study because he was older than 15 years old (in accordance with the previous project approved by the Ministry of Health of Senegal, the assembled village population, and as published elsewhere [28]. Both this study and the assent procedure were approved by the National Ethics Committee of Senegal (CNERS) and the Ethics Committee of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche IFR48, Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France (agreement numbers 09-022 and 11-017). Several other new bacterial species were isolated from this specimen using various culture conditions, including the recently described Anaerococcus senegalensis, Alistipes senegalensis, Alistipes timonensis, Peptoniphilus timonensis, Clostridium senegalense, Paenibacillus senegalensis and Bacillus timonensis, Herbaspirillum massiliense, Kurthia massiliensis, Brevibacterium senegalense, Aeromicrobium massiliense and Cellulomonas massiliensis[3-15].

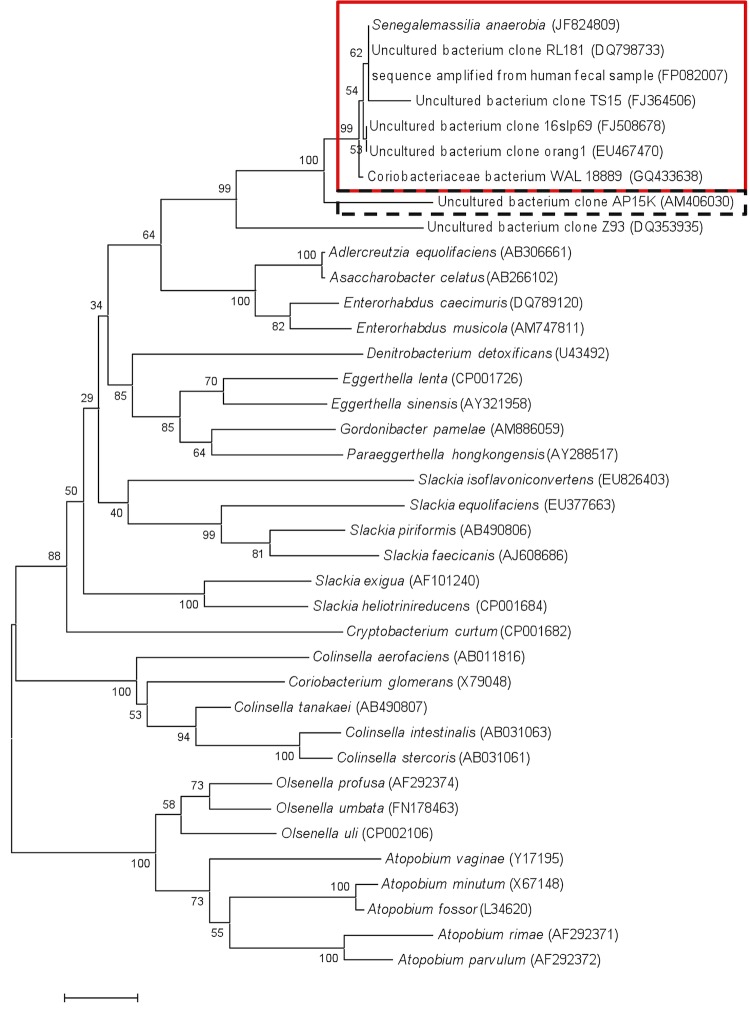

The fecal specimen was preserved at -80°C after collection and sent to Marseille. Strain JC110T (Table 1) was isolated in February 2011. The stool was preincubated for 5 days in a blood culture bottle, and then inoculated onto 5% sheep blood agar and incubated in anaerobic atmosphere at 37°C. The strain exhibited a nucleotide sequence similarity with members of the Coriobacteriaceae ranging from 85.3% with Atopobium parvulum to 92.4% with Enterorhabdus mucosicola (Figure 1). This value was lower than the 95% 16S rRNA gene sequence threshold recommended by Stackebrandt and Ebers to delineate a new genus [33]. By comparison to the NR database, strain JC110 T also exhibited nucleotide sequence similarities greater than 99% with uncultured bacterial clones detected in metagenomic studies of the human gut flora. These bacteria are most likely classified within the same species as strain JC110 (Figure 1).

Table 1. Classification and general features of Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T according to the MIGS recommendations [29].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [30] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [31] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [16] | ||

| Order Coriobacteriales | TAS [16,32] | ||

| Family Coriobacteriaceae | TAS [16,32] | ||

| Genus Senegalemassilia | TAS | ||

| Species Senegalemassilia anaerobia | IDA | ||

| Type strain JC110T | |||

| Gram stain | positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | coccobacillus | IDA | |

| Motility | motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | nonsporulating | IDA | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | IDA | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | unknown | IDA |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | anaerobic | IDA |

| Carbon source | unknown | ||

| Energy source | unknown | ||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | human gut | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | IDA |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity Biosafety level Isolation |

unknown 2 human feces |

|

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Senegal | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | September 2010 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 13.7167 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | – 16.4167 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Surface | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 51 m above sea level | IDA |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [33]. If the evidence is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the phylogenetic position of Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T relative to other type strains within the Coriobacteriaceae family. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic inferences were made using the maximum-likelihood method within the MEGA software. Numbers at the nodes are percentages of bootstrap values (500 repetitions) to generate a majority consensus tree. The scale bar indicates a 1% nucleotide sequence divergence. The red square groups sequences that exhibit degrees of similarity > 99% with S. anaerobia (same species), whereas that in the dashed-line square is 97.2% similar (same genus).

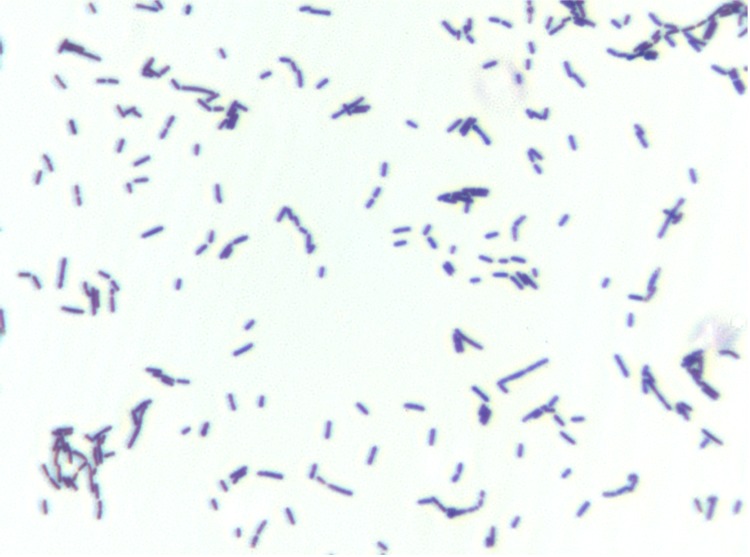

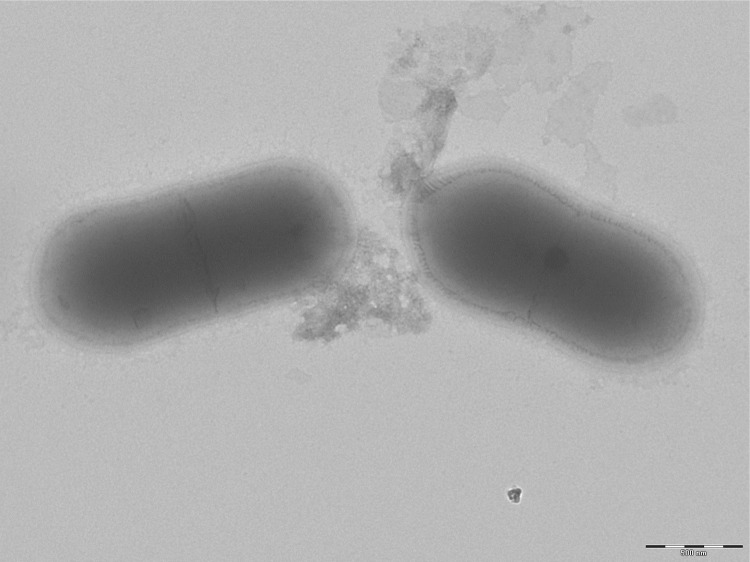

Different growth temperatures (25, 30, 37, 45°C) were tested; no growth occurred at 25°C or 45°C, weak growth occurred at 30°C, optimal growth was observed at 37°C. Colonies were transparent and smooth with 0.5 mm in diameter on blood-enriched Columbia agar and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar. Growth of the strain was tested under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions using GENbag anaer and GENbag microaer systems, respectively (BioMérieux), and in the presence of air, of 5% CO2 and in aerobic conditions. Growth only occurred under anaerobic conditions. A motility test was positive. Cells grown on agar appear as Gram-positive coccobacilli (Figure 2) and have a diameter ranging from 0.62 to 0.76 µm (mean of 0.70 µm) and a length ranging from 1.36 to 1.73 µm (mean of 1.56 µm)(Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Gram staining of S. anaerobia strain JC110T

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of S. anaerobia strain JC110T, using a Morgani 268D (Philips) at an operating voltage of 60kV.The scale bar represents 900 nm. Length and diameter were measured about 10 different bacteria.

Strain 110T exhibited neither catalase nor oxidase activities. In the API Rapid ID 32A system, positive reactions were obtained for arginine dihydrolase, and nitrate reduction. A weak reaction was obtained for alkanine phosphatase. In the API ZYM system, positive reaction was observed for Naphthlol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase and a weak reaction was observed for alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase. Negative reactions were observed for alkaline phosphatase, esterase, esterase lipase, lipase, leucine arylamidase, valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, N-acetyl- β-glucosaminidase, α-mannosidase and α-fucosidase. In the API 50CH system, all reactions were negative. S. anaerobia is susceptible to amoxicillin, imipenem, metronidazole and gentamicin but resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

The comparisons with genera of the Coriobacteriaceae family are summarized in Table 2. Senegalemassilia anaerobia JC110T shares motility with Gordonibacter pamelae,in contrast with Adlercreutzia equolifaciens, Enterorhabdus mucosicola, Eggerthela sinensis and Collinsella aerofaciens. In contrast with Collinsella aerofaciens, Senegalemassilia anaerobia was asaccharolytic. Among these species, JC110T revealed a positive reaction for nitrate reductase. Lastly, we observed within the members of Coriobacteriaceae family a large heterogeneity of DNA G+C content ranging from 60% to 66.5% [Table 2].

Table 2. Differential characteristics of six members of the Coriobacteriaceae family†.

| Properties | Senegalemassilia anaerobia |

Adlercreutzia equolifaciens | Enterorhabdus mucosicola | Eggerthella sinensis | Gordonibacter pamelae | Collinsella aerofaciens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell morphology | Coccobacilli | Coccobacilli | Rod | Rod | Coccobacilli | Chains of coccid cells |

| Oxygen requirement | Obligately anaerobic | Obligately anaerobic | Obligately anaerobic | Obligately anaerobic | Obligately anaerobic | Obligately anaerobic |

| Motility | + | – | – | – | + | – |

| Spore- formation | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Production of | ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | W | Na | Na | – | – | Na |

| Catalase | – | Na | – | + | + | Na |

| Oxidase | – | Na | – | Na | Na | Na |

| Nitrate reductase | + | – | Na | – | – | Na |

| Urease | – | – | Na | – | – | Na |

| Indole production | – | Na | – | – | – | Na |

| β-galactosidase | – | Na | Na | – | – | Na |

| β-glucosidase | – | – | Na | – | – | Na |

| Arginine arylamidase | – | + | Na | + | – | Na |

| Arginine dihydrolase | + | + | Na | + | + | Na |

| Leucine arylamidase | – | + | Na | – | – | Na |

| Acid from | ||||||

| Glucose | – | – | Na | – | – | + |

| Arabinose | – | – | Na | – | – | – |

| Ribose | – | – | Na | Na | – | – |

| Mannose | – | – | Na | – | Na | + |

| Maltose | – | – | Na | Na | Na | + |

| Mannitol | – | – | Na | Na | Na | – |

| Trehalose | – | – | Na | – | – | – |

| Cellobiose | – | – | Na | Na | Na | – |

| Galactose | – | – | Na | Na | Na | + |

| Fructose | – | – | Na | Na | Na | + |

| G+C content (mol%) | 60.9 | 64.1 to 66.5 | 64.2 | 64.9-65.6 | 66.4 | 60-61 |

| Habitat | human gut | human and rat intestine | mouse intestine | human bacteremia | human colon Crohn’s disease |

human samples |

†Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T, Adlercreutzia equolifaciens strain FCJ-B9T, Enterorhabdus mucosicola strain Mt1B8T, Eggerthella sinensis HKU14, Gordonibacter pamelae strain 7-10-1-bT and Collinsella aerofaciens JCM10188T. (w = weak, na= no available)

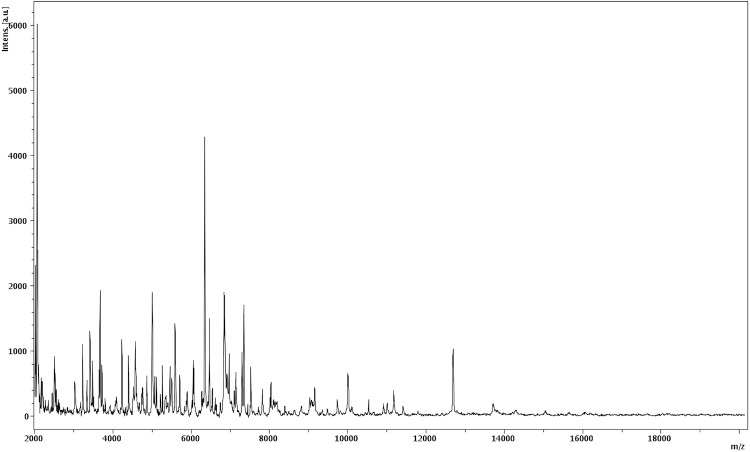

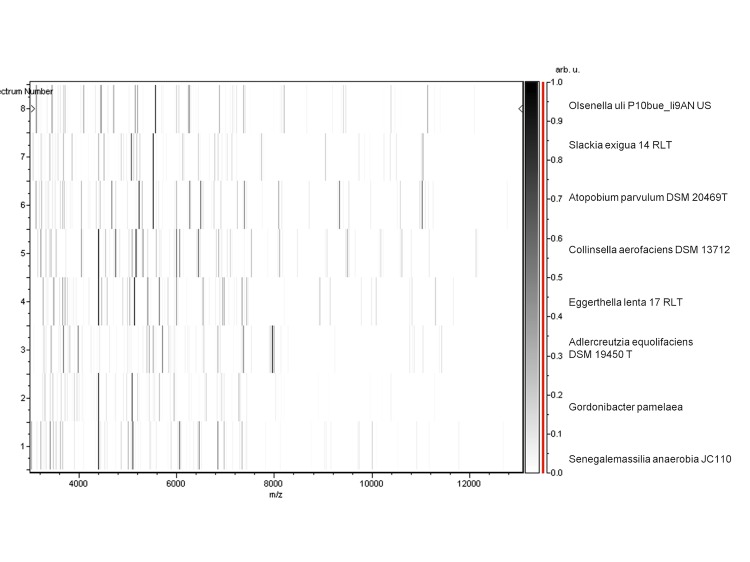

Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS protein analysis was carried out as previously described using a Microflex spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) [34]. Briefly, a pipette tip was used to pick one isolated bacterial colony from an agar plate, and to spread it as a thin film on an MTP 384 MALDI-TOF target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany). Twelve distinct deposits were done for strain JC110T from twelve isolated colonies. Each smear was overlaid with 2 µL of matrix solution (saturated solution of alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) in 50% acetonitrile, 2.5% tri-fluoracetic-acid, and allowed to dry for five minutes. Measurements were performed with a Microflex spectrometer (Bruker). Spectra were recorded in the positive linear mode for the mass range of 2,000 to 20,000 Da (parameter settings: ion source 1 (IS1), 20 kV; IS2, 18.5 kV; lens, 7 kV). A spectrum was obtained after 675 shots at a variable laser power. The time of acquisition was between 30 seconds and 1 minute per spot. The twelve JC110T spectra were imported into the MALDI BioTyper software (version 2.0, Bruker) and analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of 3,769 bacteria, which were used as reference data, in the BioTyper database. The method of identification included the m/z from 3,000 to 15,000 Da. For every spectrum, a maximum of 100 peaks taken into account and compared with spectra in the database. A score enabled the identification, of the tested species: a score > 2 with a validly published species enabled the identification at the species level, a score > 1.7 but < 2 enabled the identification at the genus level; and a score < 1.7 did not enable any identification. For strain JC110T, no significant score was obtained, suggesting that JC110T was not a member of a known species or genus. We incremented our database with the spectrum from strain JC110T (Figure 4). The gel view allowed us to highlight the spectra differences with other of Coriobactericeae family members (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Reference mass spectrum from S. anaerobia strain JC110T. Spectra from 12 individual colonies were compared and a reference spectrum was generated.

Figure 5.

Gel view comparing Senegalemassilia anaerobia JC110T spectra with other members into Coriobacteriaceae family (Olsenella uli, Slackia exigua, Atopobium parvulum, Collinsella aerofaciens, Eggerthella lenta, Adlercreutzia equolifaciens and Gordonibacter pamelaeae). The Gel View displays the raw spectra of all loaded spectrum files arranged in a pseudo-gel like look. The x-axis records the m/z value. The left y-axis displays the running spectrum number originating from subsequent spectra loading. The peak intensity is expressed by a Gray scale scheme code. The color bar and the right y-axis indicate the relation between the color a peak is displayed with and the peak intensity in arbitrary units.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position and 16S rRNA similarity to other members of the Coriobacteriaceae, and is part of a “culturomics” study of the human digestive flora aiming at isolating all bacterial species in human feces. It was the sixth genome of a species within the Coriobacteriaceae and the first genome of Senegalemassilia anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. A summary of the project information is shown in Table 3. The EMBL accession number is CAEM00000000 and consists 8 scaffolds. Table 3 shows the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance.

Table 3. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One paired-end 3 Kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platform | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 32 × |

| MIGS-30 | Assembler | Newbler version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| EMBL ID | CAEM00000000 | |

| EMBL Date of Release | November 20, 2011 | |

| Project relevance | Study of the human gut microbiome |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

Senegalemassilia anaerobia strain JC110T (= CSUR P147 = DSMZ 25959) was grown on 5% sheep blood-enriched Columbia agar (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) at 37°C in an anaerobic atmosphere. Four petri dishes were spread and resuspended in 3 × 100µl of G2 buffer (EZ1 DNA Tissue kit, Qiagen). A first mechanical lysis was performed using glass powder on a Fastprep-24 device (MP Biomedicals, Ilkirch, France) during 2×20 seconds. DNA was then treated with 2.5 µg/µL lysozyme (30 minutes at 37°C) and extracted through the BioRobot EZ 1 Advanced XL (Qiagen). The DNA was then concentrated and purified on a Qiamp kit (Qiagen). The yield and the concentration was measured by the Quant-it Picogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios_Tecan fluorometer at 25 ng/µl.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Sequencing was performed using the 3kb paired-end strategy on a Roche 454 Titanium pyrosequencer . This project was loaded twice onto a 1/8 region of a PTP Picotiterplate (Roche, Meylan, France). DNA (5µg) was mechanically fragmented on a Hydroshear device (Digilab, Holliston, MA, USA) with an enrichment size at 3-4 kb. DNA fragmentation was visualized using the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer on a DNA labchip 7500 with an optimal size of 3,215 kb. The library was constructed according to the 454 Titanium paired-end protocol. Circularization and nebulization were performed and generated a pattern with an optimum at 363 bp. After PCR amplification through 15 cycles, followed by double size selection, the single stranded paired-end library was quantified using a Quant-it Ribogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios Tecan fluorometer at 152 pg/µL. The library concentration equivalence was calculated to be 7.68E+08 molecules/µL. The library was stored at -20°C until further use.

The library was clonally amplified with 1 cpb in 3 SV-emPCR reactions with the GS Titanium SV emPCR Kit (Lib-L) v2 (Roche). The yield of the emPCR was 12.87%, in the 5 to 20% range from the Roche procedure. Approximately 340,000 beads were loaded onto each of the two 1/8 regions of GS Titanium PicoTiterPlates. Sequencing was performed using the GS Titanium Sequencing Kit XLR70. The runs were performed overnight and then analyzed on the cluster through the gsRunBrowser and Newbler assembler (Roche). A total of 256,934 passed filter wells were obtained and generated 74 Mb of DNA sequence with an average length of 289 bp. The passed filter sequences were assembled using Newbler with 90% identity and 40 bp as overlap. The final assembly yielded 8 scaffolds and 62 large contigs (>1,500 bp).

Genome annotation

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [35] with default parameters. The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against the Genbank database and the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) databases using BLASTP. The tRNAScanSE tool [36] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNAs were found by using RNAmmer [37] and BLASTn against GenBank. ORFans were identified if their BLASTp E-value was lower than 1e-03 for alignment length greater than 80 amino acids. If alignment lengths were smaller than 80 amino acids, we used an E-value of 1e-05. To estimate the mean level of nucleotide sequence similarity at the genome level between S. anaerobia and other members of the Coriobacteriaceae and among members of this family, we compared genomes two by two and determined the mean percentage of nucleotide sequence identity among orthologous ORFs using BLASTn Orthologous genes were detected using the Proteinortho software [38].

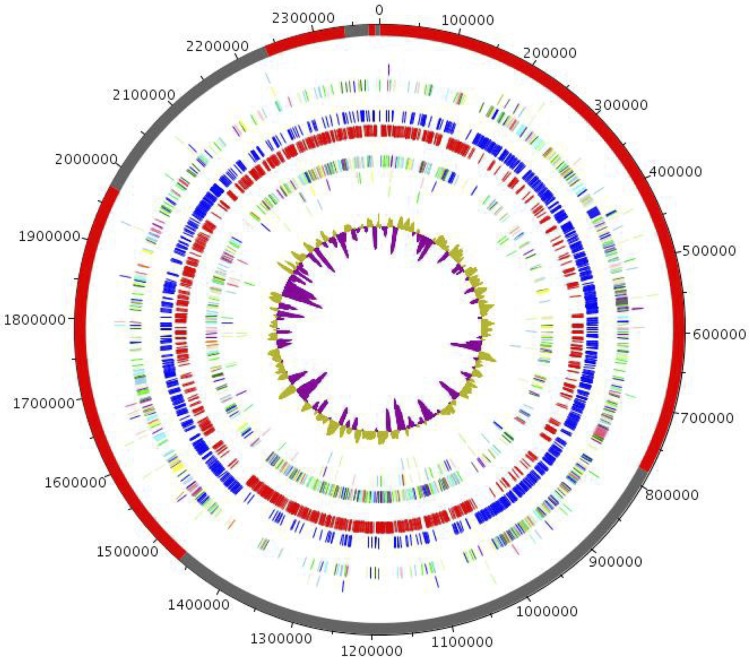

Genomes properties

The genome is 2,383,131 bp long (one chromosome, no plasmid) with a 60.9% G + C content (Table 4). Of the 1,990 predicted genes, 1,932 were protein-coding genes, and 58 were RNAs (1 rRNA operon and 55 tRNA genes). A total of 1,430 genes (68.12%) were assigned a putative function. Fifty-six genes were identified as ORFans (2,90%). The remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical proteins (330 genes = 17.08%). The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 5 and Figure 6. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 2,383,131 | - |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 1,451,434 | 60.9 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,043,582 | 85.7 |

| Total genes | 1,990 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 58 | 2.91 |

| Protein-coding genes | 1,932 | 97.09 |

| Genes with function prediction | 1,430 | 74.02 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,471 | 76.13 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 205 | 10.61 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 463 | 23.96 |

The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

Table 5. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 124 | 6.42 | Translation |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 113 | 5.84 | Transcription |

| L | 97 | 5.02 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 21 | 1.09 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 22 | 1.14 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 74 | 3.83 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 79 | 4.09 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 8 | 0.47 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 34 | 1.76 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 48 | 2.54 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 131 | 6.78 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 62 | 3.2 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 192 | 9.94 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 53 | 2.74 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 86 | 4.45 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 50 | 2.59 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 85 | 4.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 23 | 1.19 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 214 | 11.08 | General function prediction only |

| S | 116 | 6 | Function unknown |

| - | 461 | 23.85 | Not in COGs |

Figure 6.

Graphical circular map of the genome from outside to the center: Contigs (red / grey), COG category of genes on the forward strand (three circles), genes on the forward (blue circle) and reverse strands (red circle), COG category on the reverse strand (three circles), GC content.

Comparison with genomes from Coriobacteriaceae

At present, the complete genomes from Atopobium parvulum [39], Cryptobacterium curtum [40], Eggerthella lenta [41], Olsenella uli [42], and Slackia heliotrinireducens [43] are available. S. anaerobia has a smaller genome than E. lenta and S. heliotrinireducens (2,384,013 bp vs 3, 632,260 bp and 3,165,038 bp, respectively) but larger than A. parvulum, C. curtum, and O. uli (2,384,013 bp vs 1,543,805 bp, 1,617,804 bp, and 2,051,896 bp, respectively). It has a greater number of genes than A. parvulum, C. curtum and O. uli (1,900 vs 1,419, 1,425 and 1,850 genes, respectively) but fewer than E. lenta and S. helionitrireducens (3,181 and 2,858 genes, respectively), and has a higher G+C content than A. parvulum, C. curtum and S. heliotrinireducens (60.9% vs 45.69% and 50.91%, 60.21%, respectively) but smaller than E. lenta and O. uli (64.2% and 64.7%, respectively). Table 6 summarizes the numbers of orthologous genes and the average percentage of nucleotide sequence identity between the different genomes studied. The average nucleotide identity ranged from 47.74 to 71.10% within the Coriobacteriaceae family, and from 47.74% to 67.05% between S. anaerobia and other species.

Table 6. Number of orthologous genes (upper right) and average nucleotide identity levels (lower left) between pairs of genomes determined using the Proteinortho software [38].

| S. anaerobia | S. heliotrinireducens | O. uli | E. lenta | C. curtum | A. parvulum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegalemassilia anaerobia | - | 962 | 471 | 1,059 | 877 | 625 |

| Slackia heliotrinireducens | 66.94 | - | 715 | 1,019 | 832 | 646 |

| Olsenella uli | 67.05 | 67.49 | - | 736 | 611 | 694 |

| Eggerthella lenta | 47.74 | 71.10 | 68.69 | - | 908 | 670 |

| Cryptobacterium curtum | 64.78 | 65.88 | 63.12 | 66.74 | - | 606 |

| Atopobium parvulum | 62.76 | 62.51 | 65.77 | 61.52 | 63.87 | - |

Conclusion

On the basis of phenotypic (Table 2), phylogenetic and genomic analyses (Table 6), we formally propose the creation of Senegalemassilia anaerobia gen. nov., sp. nov. that contains strain JC110T. This bacterium has been found in Senegal.

Description of Senegalemassilia gen. nov.

Senegalemassilia (se.ne.ga.le.ma.si’li.a N.L. fem. N. Senegalemassilia, combination of Senegal, where the stool was collected and massilia, the latin name of Marseille, where strain JC110T was cultivated.)

Gram-positive coccobacilli. Strictly anaerobic. Mesophilic. Motile. Absent catalase, oxydase and indole productions. Positive for arginine dihydrolase, nitrate reduction and alkanine phosphatase. Habitat: human digestive tract. Type species: Senegalemassilia anaerobia.

Description of Senegalemassilia anaerobia sp. nov.

Senegalemassilia anaerobia (an.a.e.ro’bi.a. N. L. F. adj. Gr. pref. an not; Gr. N. aer air; Gr.n.bios life; N.L. adj. anaerobia anaerobe, that can live in the absence of oxygen; referring to the respiratory metabolism of organism). It has been isolated from the feces of an asymptomatic Senegalese patient.

Gram-positive coccobacilli, 0.7 µm in diameter and 1.56µm in length. Strictly anaerobic. Mesophilic. Motile and non-sporulating. Colonies are transparent and smooth with 0.5 mm in diameter on blood-enriched Columbia agar. Catalase oxydase and indole negative. Arginine dihydrolase, nitrate reduction,alkanine phosphatase, acid phosphatase and Naphtlol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase positive. Asaccharolytic. Cells are susceptible to amoxicillin, imipenem, metronidazole and gentamicin but resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The 16S rRNA and genome sequences are deposited in Genbank and EMBL under accession numbers JF824809 and CAEM00000000, respectively. The G+C content of the genome is 60.9%. Habitat: human digestive tract. The type strain JC110T (= CSUR P147 = DSMZ 25959) was isolated from the fecal flora of a healthy patient in Senegal.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Julien Paganini at Xegen company for automating the genome annotation process and Mr Ajay Mishra for his help in the determination of average genomic nucleotide sequence identities. This work was funded by the Mediterranee-Infection foundation.

References

- 1.Tindall BJ, Rossello-Mora R, Busse HJ, Ludwig W, Kämpfer P. Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:249-266 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Million M, Hugon P, Pagnier I, Robert C, Bittar F, Fournous G, Gimenez G, Maraninchi M, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:1185-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Database GOL.http://www.genomesonline.org/cgi-bin/GOLD/index.cgi

- 4.Lagier JC, El Karkouri K, Nguyen TT, Armougom F, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Anaerococcus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:116-125 10.4056/sigs.2415480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokcha S, Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Million M, Leroy Q, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Bacillus timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:346-355 10.4056/sigs.2776064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra AK, Gimenez G, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:304-314 10.4056/sigs.2625821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Mishra AK, Ngyuen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Alistipes timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:315-324 10.4056/sigs.2685917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Clostridium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 6:386-395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:1-11 10.4056/sigs.2956294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Rivet R, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Paenibacillus senegalensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:70-81 10.4056/sigs.3054650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagier JC, Gimenez G, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Herbaspirillum massiliense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:200-209 10.4056/sigs.3086474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roux V, El Karkouri K, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Kurthia massiliensis sp. nov. [Epub ahead of print]. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:221-232 10.4056/sigs.3206554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokcha S, Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Brevibacterium senegalense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:233-245 10.4056/sigs.3256677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramasamy D, Kokcha S, Lagier JC, N’Guyen TT, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Aeromicrobium massilense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci 2012; 7:246-257 10.4056/sigs.3306717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagier JC, Ramasamy D, Rivet R, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Cellulomonas massiliensis sp. nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruo T, Sakamoto M, Ito C, Toda T, Benno Y. Adlercreutzia equolifaciens gen. nov., sp. nov., an equol-producing bacterium isolated from human faeces, and emended description of the genus Eggerthella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:1221-1227 10.1099/ijs.0.65404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minamida K, Ota K, Nishimukai M, Tanaka M, Abe A, Sone T, Tomita F, Hara H, Asano K. Asaccharobacter celatus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from rat caecum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:1238-1240 10.1099/ijs.0.64894-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins MD, Wallbanks S. Comparative sequence analyses of the 16S rRNA genes of Lactobacillus minutus, Lactobacillus rimae and Streptococcus parvulus: proposal for the creation of a new genus Atopobium. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1992; 74:235-240 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kageyama A, Benno Y, Nakase K. Phylogenetic and phenotypic evidence for the transfer of Eubacterium aerofaciens to the genus Collinsella as Collinsella aerofaciens gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:557-565 10.1099/00207713-49-2-557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas F, König H. Coriobacterium glomerans gen. nov., sp. nov. from the intestinal tract of the red soldier bug. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1988; 38:382-384 10.1099/00207713-38-4-382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakazawa F, Poco SE, Ikeda T, Sato M, Kalfas S, Sundqvist G, Hoshino E. Cryptobacterium curtum gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus of Gram-positive anaerobic rod isolated from human oral cavities. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:1193-1200 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson RC, Rasmussen MA, Jensen NS, Allison MJ. Denitrobacterium detoxificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a ruminal bacterium that respires on nitrocompounds. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:633-638 10.1099/00207713-50-2-633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wade WG, Downes J, Dymock D, Hiom S, Weightman AJ, Dewhirst FE, Paster BJ, Tzellas N, Coleman B. The family Coriobacteriaceae: reclassification of Eubacterium exiguum (Poco et al. 1996) and Peptostreptococcus heliotrinreducens (Lanigan 1976) as Slackia exigua gen. nov., comb. nov. and Slackia heliotrinireducens gen. nov., comb. nov., and Eubacterium lentum (Prevot 1938) as Eggerthella lenta gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999; 49:595-600 10.1099/00207713-49-2-595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clavel T, Charrier C, Braune A, Wenning M, Blaut M, Haller D. Isolation of bacteria from the ileal mucosa of TNFdeltaARE mice and description of Enterorhabdus mucosicola gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:1805-1812 10.1099/ijs.0.003087-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Würdemann D, Tindall BJ, Pukall R, Lunsdorf H, Strompl C, Namuth T, Nahrstedt H, Wos-Oxley M, Ott S, Schreiber S, Timmis KN, Oxley AP. Gordonibacter pamelaeae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the Coriobacteriaceae isolated from a patient with Crohn's disease, and reclassification of Eggerthella hongkongensis Lau et al. 2006 as Paraeggerthella hongkongensis gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:1405-1415 10.1099/ijs.0.005900-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dewhirst FE, Paster BJ, Tzellas N, Coleman B, Downes J, Spratt DA, Wade WG. Characterization of novel human oral isolates and cloned 16S rDNA sequences that fall in the family Coriobacteriaceae: description of Olsenella gen. nov., reclassification of Lactobacillus uli as Olsenella uli comb. nov. and description of Olsenella profusa sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:1797-1804 10.1099/00207713-51-5-1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J, Dieye-Ba F, Roucher C, Bouganali C, Badiane A, et al. Malaria morbidity and pyrethroid resistance after the introduction of insecticide-treated bednets and artemisinin-based combination therapies: a longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:925-932 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archae, Bacteria, and Eukarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today 2006; 33:152-155 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:543-551 10.1086/600885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prodigal. http://prodigal.ornl.gov

- 36.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. t-RNAscan-SE: a program for imroved detection of transfer RNA gene in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lechner M, Findeib S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: Detection of (Co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:124 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Copeland A, Sikorski J, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Del Rio TG, Lucas S, Chen F, Tice H, Pitluck S, Cheng JF, et al. Complete genome sequence of Atopobium parvulum type strain (IPP 1246). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:166-173 10.4056/sigs.29547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mavrommatis K, Pukall R, Rohde C, Chen F, Sims D, Brettin T, Kuske C, Detter JC, Han C, Lapidus A, et al. Complete genome sequence of Cryptobacterium curtum type strain (12-3). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:93-100 10.4056/sigs.12260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders E, Pukall R, Abt B, Lapidus A, Glavina Del RT, Copeland A, Tice H, Cheng JF, Lucas S, Chen F, et al. Complete genome sequence of Eggerthella lenta type strain (IPP VPI 0255). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:174-182 10.4056/sigs.33592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Göker M, Held B, Lucas S, Nolan M, Yasawong M, Glavina Del RT, Tice H, Cheng JF, Bruce D, Detter JC, et al. Complete genome sequence of Olsenella uli type strain (VPI D76D-27C). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 3:76-84 10.4056/sigs.1082860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pukall R, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Copeland A, Glavina Del RT, Lucas S, Chen F, Tice H, Cheng JF, Chertkov O, et al. Complete genome sequence of Slackia heliotrinireducens type strain (RHS 1). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:234-241 10.4056/sigs.37633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]