Abstract

Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is a chemolithoautotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacterium that belongs to the family Nitrosomonadaceae within the phylum Proteobacteria. Ammonia oxidation is the first step of nitrification, an important process in the global nitrogen cycle ultimately resulting in the production of nitrate. Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is an ammonia oxidizer of high interest because it is adapted to low ammonium and can be found in freshwater environments around the world. The 3,783,444-bp chromosome with a total of 3,553 protein coding genes and 44 RNA genes was sequenced by the DOE-Joint Genome Institute Program CSP 2006.

Keywords: Nitrosomonas, Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, Ammonia oxidation, nitrification, nitrogen cycle, freshwater, oligotrophic

Introduction

Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is a betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizer. The genus name Nitrosomonas derived from nitrosus (Latin: nitrous) and monad (Greek: a unit) meaning nitrite producing unit. Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 was enriched and isolated from freshwater sediment [1]. Closely related strains can be found in freshwater environments around the world [2-6]. Other Nitrosomonas species have been isolated from freshwater and marine systems, wastewater treatments plants and soils [7,8]. The genome sequence of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is the fifth genome of the betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers that has been completed by DOE-Joint Genome Institute (CP002876.1) [9-12]. Here we present summary classification and a set of features for Nitrosomonas sp. Is79, together with the description of the complete genome sequence and annotation.

Classification and features

Fourteen species with valid published names are currently assigned to the Nitrosomonadaceae [13-19]. Besides these described species, many undescribed isolates are available [7,20-22]. These strains were isolated from freshwater, marine systems, wastewater and soils, share the traits of aerobic chemolithoautotrophic metabolism using ammonia as an electron donor, and carbon dioxide as carbon source (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification and general features of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 according to the MIGS recommendations [23].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Domain Bacteria | TAS [24] | |

| classification | Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [25] | |

| Class Betaproteobacteria | TAS [26,27] | ||

| Order Nitrosomonadales | TAS [27,28] | ||

| Family Nitrosomonadaceae | TAS [27,29] | ||

| Genus Nitrosomonas | TAS [13,30-32] | ||

| Species Nitrosomonas sp | IDA | ||

| Type strain Is79 | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | negative | NAS | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped, short | NAS | |

| Motility | not reported | ||

| Sporulation | none | NAS | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | NAS | |

| Optimum temperature | not reported | ||

| Salinity | < 50mM NaCl, very sensitive to salt | TAS [1,33] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | carbon dioxide | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | ammonia | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | chemolithoautotroph | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-23 | Isolation and growth conditions | Isolation after enrichment in chemostat under low substrate concentrations, adapted to low ammonium concentrations in the medium |

TAS [1] |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | freshwater | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | None | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [34] | |

| Isolation | freshwater sediment | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Lake Drontermeer (Netherlands) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 52°58’N | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 5°50’E | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | 0.5 m (root zone in the littoral zone of the lake) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | around sea level | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | Fall 1997 | TAS [1] |

Evidence codes – IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e. a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e. not directly observed for living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from a living isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Strain Is79 was isolated into pure culture by A. Bollmann in 2001 and maintained in liquid stock cultures since then, being transferred to fresh medium approximately once per month. The strain has not been deposited in a culture collection, but can be obtained from A.B. upon request. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, the strains most closely related to Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 are Nitrosomonas oligotropha Nm10 with 97.8% sequence identity and Nitrosomonas ureae Nm45 with 97% sequence identity (Figure 1). The sequence of the single 16S rRNA gene copy in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 differs by two nucleotides from the previously published 16S rRNA gene sequence (AJ621026), both of which are insertions into the whole genome sequence.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the position of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 relative to the other described strains within the family. Nitrosomonas sp. AL212 is not a formally described strain, but was included because the whole genome of this strain became recently available [12]. The tree was constructed from 1,272 aligned characters of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion and rooted in accordance with a current taxonomy using the software package MEGA [35]. Numbers adjacent to the branches are support values from 1,000 ML bootstrap replicates (left) and from 1,000 maximum parsimony bootstrap replicates (right) if larger than 60% [35]. Strains with whole genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [36] are shown in red and the published in red-bold: Nitrosomonas europaea (AL954747), Nitrosomonas eutropha (CP000450), Nitrosospira multiformis (CP000103), Nitrosomonas sp. AL212 (CP002552) and Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 (CP02876).

Growth studies show that Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 has a chemolithoautotrophic metabolism using ammonia as energy source producing nitrite. The strain is strictly aerobic and fixing carbon autotrophically from carbon dioxide via the Calvin cycle [37]. Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is adapted to low ammonium concentrations and has been isolated after enrichment in continuous culture under ammonium-limited conditions [1]. Further experiments showed that Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 was able to grow and outcompete Nitrosomonas europaea under ammonium-limited conditions [38] and has Ks and Km values for ammonium lower than other ammonia-oxidizing bacteria [Bollmann unpublished].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

The organism was selected for sequencing as part of DOE-JGI program CSP 2006 because it is adapted to growth at low ammonium concentrations. The genome sequence is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [36] and the complete genome is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by DOE-Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three 454 pyrosequence libraries, standard and two paired end (9 and 7 kb average insert size) and one Illumina library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 Titanium, Illumina |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 454 Titanium: 36.6 × and Illumina: 910.8 x |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.3; VELVET version 1.0.13 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP002876 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | July 05, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01870 | |

| NCBI project ID | 52837 | |

| Database: IMG | 2505679045 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 |

| Project relevance | Environmental strain, nitrogen cycle |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The strain Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 was grown in mineral salts medium with 5mM ammonium at 27°C until all ammonium was consumed [39]. DNA was isolated using the protocol recommended by JGI (Bacterial genomic DNA isolation using CTAB). Size and quality of the bulk DNA was determined according to DOE-JGI guidelines. The size of the gDNA was larger than 23 kbp as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The draft genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 was generated at the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using a combination of Illumina [40] and 454 technologies [41]. For the genome, we constructed and sequenced an Illumina GAii shotgun library which generated 46,913,976 reads totaling 3,565.5 Mb, a 454 Titanium standard library which generated 252,425 reads and 2 paired end 454 libraries with an average insert size of 7 kb, and 9 kb which generated 401,484 reads totaling 173.6 Mb of 454 data. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at the JGI website [42]. The initial draft assembly contained 250 contigs in 3 scaffolds. The 454 Titanium standard data and the 454 paired end data were assembled together with Newbler, version 2.3-Prerelease-6/30/2009. The Newbler consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 2 kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). Illumina sequencing data were assembled with VELVET, version 1.0.13 [43] and the consensus sequence were computationally shredded into 1.5kb overlapping fake reads (shreds). We integrated the 454 Newbler consensus shreds, the Illumina VELVET consensus shreds and the read pairs in the 454 paired end library using parallel phrap, version SPS – 4.24 (High Performance Software, LLC). The software Consed [44-46] was used in the following finishing process. Illumina data were used to correct potential base errors and increase the consensus quality using the software Polisher developed at JGI [Lapidus, unpublished]. Possible mis-assemblies were corrected using gapResolution [Han, unpublished], Dupfinisher [47] or sequencing cloned bridging PCR fragments with subcloning. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, by PCR and by Bubble PCR [Cheng, unpublished] primer walks. A total of 667 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The total size of the genome is 3,783,444 bp and the final assembly is based on 138.9 Mb of 454 draft data, which provide an average 36.6 coverage of the genome and 3,461Mb of Illumina draft data, which provide average 910.8× coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [48] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [49]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [50], RNAmmer [51], Rfam [52], TMHMM [53], and signal P [54].

Genome properties

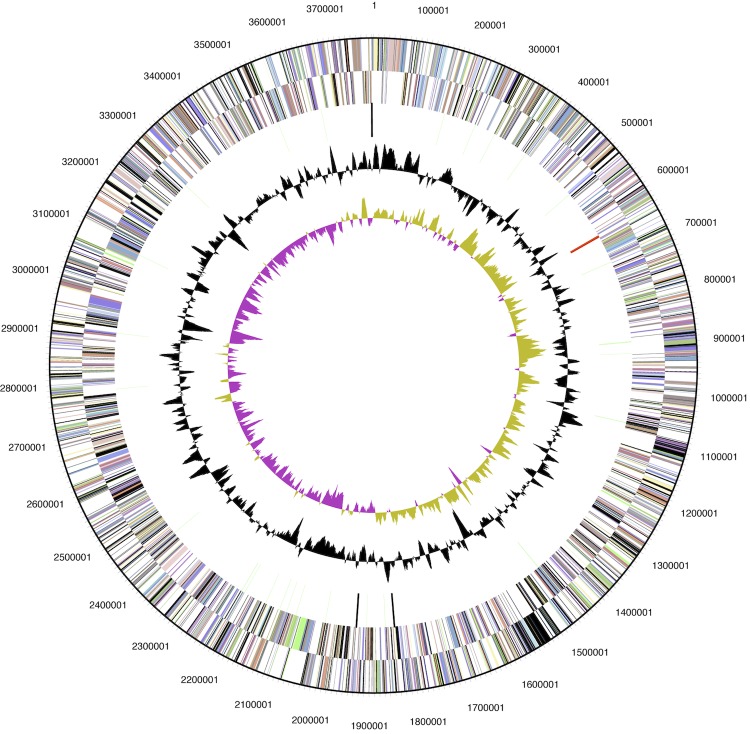

The genome consists of a 3,783,444-bp long chromosome; the largest of all sequenced and published betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers [9-12]. The genome has a GC content of 45.4%. The genome contained 3,597 predicted genes of which 3,553 were protein-coding genes, 44 RNAs, and 181 pseudogenes (Figure 2). The majority of the protein-coding genes (63.64%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins (Table 3). The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Graphical map of the genome. From the outside to the center: Genes on forward strand and Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,783,444 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,166,256 | 83.69% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,719,313 | 45.44% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 3,597 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 44 | 1.22% |

| rRNA operons | 1 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 3,553 | 98.78% |

| Pseudo genes | 181 | 5.03% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2,289 | 63.64% |

| Genes with paralog clusters | 1,591 | 44.23% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,383 | 66.25% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,554 | 71.00% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,130 | 31.42% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 860 | 23.91% |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 |

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 167 | 6.34 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 7 | 0.27 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 128 | 4.86 | Transcription |

| L | 270 | 10.24 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.04 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 39 | 1.48 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 49 | 1.86 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 211 | 8.00 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 139 | 5.27 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 94 | 3.57 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 87 | 3.30 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 132 | 5.01 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 146 | 5.54 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 93 | 3.53 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 152 | 5.77 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 56 | 2.12 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 115 | 4.36 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 79 | 3.00 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 122 | 4.63 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 57 | 2.16 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 259 | 9.83 | General function prediction only |

| S | 233 | 8.84 | Function unknown |

| - | 1214 | 33.75 | Not in COG’s |

Insights from the genome sequence

Ammonia monooxygenase

The ammonia monooxygenase encodes the first enzyme in the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite via hydroxylamine [37]. Three amoCAB operons can be detected in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 (Figure 3) and downstream of two of these operons the hypothetical genes (amoE and amoD [55]) were identified. The genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 contains two single copies of the amoC gene. The copper resistance genes, copC and copD were not detected downstream of any of the amoCAB operons as it was identified in all other described betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers [9-12,56].

Figure 3.

Organization of the amo gene clusters in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79.

Hydroxylamine oxidoreductase

The hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) is the second enzyme in ammonia oxidation, catalyzing the oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite [37]. As all other betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers, Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 encodes three syntenous hao operons consisting of the genes haoA encoding the octaheme cytochrome c protein subunit that forms the functional HAO complex, haoB encoding an uncharacterized gene product, cycA encoding cytochrome c554, and cycB encoding the quinone reductase, cytochrome cM552.

Nitrogen oxide metabolism

A copper-containing nitrite reductase (nirK) was detected in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79. As detected in N. multiformis and Nitrosomonas sp. AL212, the nirK gene exists as a singleton in the genome, which is in contrast to its position in the genomes of N. europaea and N. eutropha where nirK is a member of a conserved multigene cluster (Table 5) [9-12,56].

Table 5. Presence and absence of genes involved in nitrogen oxide metabolism based on [9-12].

| Genes | NE* | Neut* | Nmul* | NAl212* | Nit79A3* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrite reductase | nirK | + | + | + | + | 2335 |

| Nitrogen sensitive transcriptional regulator | nsrR | + | + | - | - | - |

| Nitric oxide reductase | norCBQD | + | + | + | + | - |

| Nitric oxide detoxification | ||||||

| Heme-copper nitric oxide reductase | norSY-senC-orf1 | + | + | + | - | - |

| Cytochrome c′-beta | cytS | + | + | + | + | 0363 |

| Cytochrome P460 | cytL | + | + | - | + | 1628 |

| Nitrosocyanin | ncyA | + | + | + | + | - |

* NE: N.europaea; Neut: N.eutropha; Nmul: N.multiformis; NAL212: Nitrosomonas sp. AL212; Nit79A3: Nitrosomonas sp. Is79

(+ presence of the gene in the genome; - absence of the gene from the genome; numbers present the position of the genes in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79)

The nitrite or nitric oxide responsive transcription factor nsrR [57] is missing in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79, indicating that Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 might have different response mechanisms to nitrite and nitric oxide than N. europaea or N. eutropha (Table 5) [9,10].

Genes encoding enzymes for nitric oxide reduction to nitrous oxide (norCBQD) were found in all betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers except again in Nitrosomonas sp. Is79. Genes found in the genomes of most chemolithotrophic ammonia oxidizers encoding additional inventory implicated in nitric oxide detoxification to prevent nitrosative stress (cytochrome P460, cytochrome c′-beta [58];) (Table 5) were also identified in the genome Nitrosomonas sp. Is79; however, the genes encoding sNOR were absent. Based on these results it is very likely that Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 can avoid nitrosative stress caused by nitric oxide [59]. In addition, it is likely that Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 cannot reduce nitric oxide to nitrous oxide via nitrifier denitrification [60], but may use an alternate pathway as demonstrated for the nitrifying methanotroph, Methylococcus capsulatus strain Bath [61,62].

Finally and in contrast to all other betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers, the gene encoding the red copper protein nitrosocyanin [63] was not identified in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79. It is currently unclear what implications the absence of this gene may have on the metabolism of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79, because the function of the protein itself is still elusive.

Ammonia transporter

The gene encoding an ammonia transporter (amtB type) was detected in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79. Ammonia transporters are needed for the acquisition of ammonia/ammonium for assimilation. The function of these genes in ammonia oxidizers that are adapted to low ammonium concentrations is of particular interest also because the process of nitrogen assimilation competes directly with the bacterium’s need for ammonia to sustain catabolism or the generation of energy.

Urease

The enzyme urease is responsible for hydrolyzing urea to yield ammonium and carbon dioxide, thereby increasing the substrates for N and C assimilation in the cytoplasm. While the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 lacks the gene cluster encoding urea hydrolase (ureABCDEFJ) [64]; the genes encoding biotin-containing urea carboxylase and the putative allophanate hydrolase were detected. It has been suggested that the products of these genes convert urea to ammonium and carbon dioxide while consuming metabolic energy (ATP). Incubation of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 in the presence of urea did not result in the production of nitrite [Sedlacek and Bollmann, unpublished] indicating that urea was not degraded, and that expression of these genes might be regulated through a network controlled by the energy status of the cell.

Hydrogenase

The genome of Nitrosomonas Is79 contained most of the putative [NiFe] hydrogenase-encoding genes found in the genome of N. multiformis [11]. However, one of the hypothetical proteins is missing, and the genes are scattered over the genome instead of being members of single gene cluster as in N. multiformis [11].

Carbon dioxide fixation

As observed in all ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 fixes carbon dioxide via the Calvin cycle involving the main enzyme RuBisCO (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase). The genomes of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 and Nitrosomonas sp. AL212 [12] encoded two copies of the RuBisCO operon (Figure 4). One copy belongs to form IA (green-like) RuBisCO and is closely related to the RuBisCO in N. europaea and N. eutropha, while the other copy belongs to form IC (red-like) RuBisCO and is closely related to the enzyme in N. multiformis (Figure 4). The form A RuBisCO is not associated with the genes for the carboxysome as in N. eutropha [10]. The two RuBisCO copies differ in their kinetic properties. Bacteria with RuBisCO form IA have a higher affinity for carbon dioxide than organisms with RuBisCO form IC [65]. Therefore it is very likely that ammonia oxidizers with two different gene copies of the RuBisCO gene have a higher flexibility with respect to the carbon dioxide availability in the environment.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers inferred using the Maximum Likelihood criterion using the software package MEGA [35] based on the protein sequence of the large subunit of the RuBisCO (cbbL). The alignment was inferred by ClustalW software [35]. Numbers adjacent to the branches are support values from 1,000 ML bootstrap replicates if higher than 60% [35].

Other genes of interest

When comparing the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 with the other available genomes of betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers, several genes and operons were detected that were missing in or unique to the investigated strain.

Potassium transporters

The genomes of N. europaea, N. eutropha, N. multiformis and Nitrosomonas sp. AL212 encode the genes phaABCDEFG for a NADH driven potassium (cation) proton antiporter. While this potassium transporter was not detected in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79, the genes for another high affinity ATP driven potassium transporter (kdpABC) were found. These three genes encoding the potassium transporter ATPase (Nit79A3_1970-1972) were upstream of an osmosensitive signal transduction histidine kinase (kdpD) and a two component transcriptional regulator (kdpE). The kdp operon encodes an inducible high affinity potassium transport system that will be expressed under potassium deficiency [66,67]. Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is known to be adapted to low nutrient concentrations and oligotrophic conditions. The presence of this high affinity transport system could be an adaptation to low ion strength environments.

Iron transport

The genome of N. europaea was characterized by a high number of different kinds of iron transporters [9] and all other genomes including Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 contained high affinity iron transporters. In addition a low affinity iron permease was detected in the genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 (Nit79A3_3148). This enzyme has been characterized well in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is involved in transport of iron, copper and zinc [68]. These authors discuss the possibility that the high affinity transport systems are active under limiting conditions, while the iron permease becomes active under non-limiting conditions. The enzyme might have the same function in Nitrosomonas sp. Is79.

Conclusion

The genome of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 is the largest betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizer genome sequenced to date. The genome shows differences in gene content when compared to other betaproteobacterial ammonia oxidizers, some of which might have importance for the adaptation to low environmental ammonia concentrations. We believe that the study of this inventory – missing or unique - will help to elucidate the adaptation of ammonia oxidizers to oligotrophic environments.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE-JGI) Community Sequencing Program 2006 to JMN. The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The collaborative project was supported by NSF Research Coordination Network grant 0541797 (Nitrification Network).

References

- 1.Bollmann A, Laanbroek HJ. Continuous culture enrichments of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria at low ammonium concentrations. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2001; 37:211-221 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00868.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen GY, Qiu SL, Zhou YY. Diversity and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in eutrophic and oligotrophic basins of a shallow Chinese lake (Lake Donghu). Res Microbiol 2009; 160:173-178 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coci M, Bodelier PLE, Laanbroek HJ. Epiphyton as a niche for ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: Detailed comparison with benthic and pelagic compartments in shallow freshwater lakes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:1963-1971 10.1128/AEM.00694-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bie M, Speksnijder A, Kowalchuk G, Schuurman T, Zwart G, Stephen J, Diekmann O, Laanbroek HJ. Shifts in the dominant populations of ammonia-oxidizing beta-subclass Proteobacteria along the eutrophic Schelde estuary. Aquat Microb Ecol 2001; 23:225-236 10.3354/ame023225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrmann M, Saunders AM, Schramm A. Effect of lake trophic status and rooted macrophytes on community composition and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:3127-3136 10.1128/AEM.02806-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speksnijder AG, Kowalchuk G, Roest K, Laanbroek HJ. Recovery of a Nitrosomonas-like 16S rDNA sequence group from freshwater habitats. Syst Appl Microbiol 1998; 21:321-330 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80040-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koops HP, Purkhold U, Pommerening-Roeser A, Timmermann G, Wagner M. The lithoautotrophic Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. The Prokaryotes 2006; 5:778-811 10.1007/0-387-30745-1_36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kowalchuk GA, Stephen J. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: A model for molecular microbial ecology. Annu Rev Microbiol 2001; 55:485-529 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chain P, Lamerdin J, Larimer F, Regala W, Lao V, Land M, Hauser L, Hooper A, Klotz M, Norton J, et al. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J Bacteriol 2003; 185:2759-2773 10.1128/JB.185.9.2759-2773.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein LY, Arp DJ, Berube PM, Chain PSG, Hauser L, Jetten MSM, Klotz MG, Larimer FW, Norton JM, op den Camp H, et al. Whole-genome analysis of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrosomonas eutropha C91: implications for niche adaptation. Environ Microbiol 2007; 9:2993-3007 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norton JM, Klotz MG, Stein LY, Arp DJ, Bottomley PJ, Chain PSG, Hauser LJ, Land ML, Larimer FW, Shin MW, et al. Complete genome sequence of Nitrosospira multiformis, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium from the soil environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:3559-3572 10.1128/AEM.02722-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suwa Y, Norton J, Bollmann A, Klotz MG, Stein LY, Laanbroek HJ, Arp DJ, Goodwin JA, Chertkov O, Held B, et al. Genome sequence of Nitrosomonas sp. strain AL212, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium sensitive to high levels of ammonia. J Bacteriol 2011; 193:5047-5048 10.1128/JB.06107-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winogradsky S. Contributions a la morphologie des organisms de la nitrification. Arch Sci Biol St. Petersburg 1892; 1:87-137.

- 14.Winogradsky S, Winogradski H. Etudes sur la microbiologie du sol. VII: Nouvelles recherches sur les organisms de la nitrification. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1933 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koops H, Boettcher B, Moeller U, Pommerening-Roeser A, Stehr G. Classification of 8 new species of Ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria – Nitrosomonas communis sp-nov, Nitrosomonas ureae sp-nov, Nitrosomonas aestuarii sp-nov, Nitrosomonas marina sp-nov, Nitrosomonas nitrosa sp-nov, Nitrosomonas eutropha sp-nov, Nitrosomonas oligotropha sp-nov and Nitrosomonas halophila sp-nov. J Gen Microbiol 1991; 137:1689-1699 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson SW, Graham L, Remsen C, Valois F. A lobular Ammonia-oxidizing Bacterium Nitrosolobus multiformis nov-gen nov sp. Arch Mikrobiol 1971; 76:183-203 10.1007/BF00409115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watson SW. Reisolation of Nitrosospira briensis S Winogradsky and H Winogradsky 1933. Arch Mikrobiol 1971; 75:179-188 10.1007/BF00408979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harms H, Koops H, Wehrmann H. Ammonia-oxidizing Bacterium, Nitrosovibrio tenuis nov-gen nov-sp. Arch Mikrobiol 1976; 108:105-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones R, Morita R, Koops HP, Watson S. A new marine Ammonium-oxidizing Bacterium, Nitrosomonas cryotolerans sp-nov. Can J Microbiol 1988; 34:1122-1128 10.1139/m88-198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aakra A, Utaker JB, Pommerening Roeser A, Koops HP, Nes IF. Detailed phylogeny of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria determined by rDNA sequences and DNA homology values. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001; 51:2021-2030 10.1099/00207713-51-6-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suwa Y, Imamura Y, Suzuki T, Tashiro T, Urushigawa Y. Ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria with different sensitivities to (NH4)(2)SO4 in activated sludges. Water Res 1994; 28:1523-1532 10.1016/0043-1354(94)90218-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suwa Y, Sumino T, Noto K. Phylogenetic relationships of activated sludge isolates of ammonia oxidizers with different sensitivities to ammonium sulfate. J Gen Appl Microbiol 1997; 43:373-379 10.2323/jgam.43.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl.nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, Vol. 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class II. Betaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, Vol. 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 575. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Order V. Nitrosomonadales ord. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, Vol. 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 863. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Family I. Nitrosomonadacaea fam. nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition, Vol. 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 864. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson SW. Genus IV. Nitrosomonas Winogradsky 1892, 127; Nom. cons. Opin. 23, Jud. Comm. 1958, 169. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 453-454. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Judicial Commission Opinion 23. Rejection of the Generic Names Nitromonas Winogradsky 1890 and Nitromonas Orla-Jensen 1909, Conservation of the Generic Names Nitrosomonas Winogradsky 1892, Nitrosococcus Winogradsky 1892, and the Designation of the Type Species of these Genera. Int Bull Bacteriol Nomencl Taxon 1958; 8:169-170 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koops HP. Pommerening_Röser, A. Distribution and ecophysiology of the nitrifying bacteria emphasizing cultured species. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2011; 37:1-9 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00847.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Classification of. Bacteria and Archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 35.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28:2731-2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagani I, Liolios K, Jansson J, Chen IMA, Smirnova T, Nosrat B, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.4: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D571 10.1093/nar/gkr1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arp D, Sayavedra-Soto L, Hommes N. Molecular biology and biochemistry of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch Microbiol 2002; 178:250-255 10.1007/s00203-002-0452-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bollmann A, Bar-Gilissen M, Laanbroek HJ. Growth at low ammonium concentrations and starvation response as potential factors involved in niche differentiation among ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002; 68:4751-4757 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4751-4757.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bollmann A, French E, Laanbroek HJ. Isolation, cultivation and characterization of ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria and Archaea adapted to low ammonium concentrations. In: Klotz MG (ed), Methods in Enzymology, Academic press, 2005, p 55-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett S. Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics 2004; 5:433-438 10.1517/14622416.5.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 2005; 437:376-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DOE Joint Genome Institute http://www.jgi.doe.gov

- 43.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18:821-829 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 1998; 8:175-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res 1998; 8:186-194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res 1998; 8:195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han C, Chain PSG. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher CSREA Press. In Arabnia AR, Valafar H, editors. Proceedings of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics and computational biology; 2006 June 26-29; p141-146 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locasio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: Procaryotic gene recognition and translation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagesen K, Hallin PF, Rodland E, Staerfeld HH, Rognes R, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent annotation of rRNA genes in genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:439-441 10.1093/nar/gkg006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genome. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: Signal IP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Sheikh AF, Poret-Peterson AT, Klotz MG. Characterization of two new genes, amoR and amoD, in the amo operon of the marine ammonia oxidizer Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:312-318 10.1128/AEM.01654-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arp DJ, Chain PSG, Klotz MG. The impact of genome analyses on our understanding of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 2007; 61:503-528 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beaumont HJ, Lens S, Reijnders W, Westerhoff H, van Spanning R. Expression of nitrite reductase in Nitrosomonas europaea involves NsrR, a novel nitrite-sensitive transcription repressor. Mol Microbiol 2004; 54:148-158 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elmore BO, Bergmann DJ, Klotz MG, Hooper AB. Cytochromes P460 and c'-beta; a new family of high-spin cytochromes c. FEBS Lett 2007; 581:911-916 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klotz MG, Stein LY. Genomics of Ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria and Insights into their evolution. In: Ward BB, Arp DJ, Klotz MG (eds), Nitrification, ASM Press, 2011, p 57-94. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stein LY. Heterotrophic Nitrification and Nitrifier Denitrification. In: Ward BB, Arp DJ, Klotz MG (eds), Nitrification, ASM Press, 2011, p 95-116. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell MA, Nyerges G, Kozlowski JA, Poret-Peterson AT, Stein LY, Klotz MG. Model of the molecular basis for hydroxylamine oxidation and nitrous oxide production in methanotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2011; 322:82-89 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poret-Peterson AT, Graham JE, Gulledge J, Klotz MG. Transcription of nitrification genes by the methane-oxidizing bacterium, Methylococcus capsulatus strain bath. ISME J 2008; 2:1213-1220 10.1038/ismej.2008.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arciero DM, Pierce B, Hendrich M, Hooper A. Nitrosocyanin, a red cupredoxin-like protein from Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochemistry 2002; 41:1703-1709 10.1021/bi015908w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koper TE, El-Sheikh AF, Norton JM, Klotz MG. Urease-encoding genes in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004; 70:2342-2348 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2342-2348.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Badger MR, Bek EJ. Multiple RUBISCO forms in Proteobacteria: their functional significance in relation to CO2 acquisition by the CBB cycle. J Exp Bot 2008; 59:1525-1541 10.1093/jxb/erm297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alahari A, Ballal A, Apte SK. Regulation of potassium-dependent Kdp-ATPase expression in the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena torulosa. J Bacteriol 2001; 183:5778-5781 10.1128/JB.183.19.5778-5781.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Altendorf K, Siebers A, Epstein W. The KDP ATPase of Escherichia coli. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1992; 671:228-243 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb43799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hassett R, Dix DR, Eide DJ, Kosman DJ. The Fe(II) permease Fet4p functions as a low affinity copper transporter and supports normal copper trafficking in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J 2000; 351:477-484 10.1042/0264-6021:3510477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]