SUMMARY

It is known that ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels regulate the membrane potential of smooth muscle cells and vascular tone. Because their activity is altered during ageing, many pharmacological treatments aimed at improving KATP channel and cardiovascular functions have been evaluated. Nicorandil, a KATP channel opener, nitric oxide (NO) donor and anti-oxidant, induces vasodilation, decreases blood pressure and exhibits cardioprotection in ageing, as well as after ischaemia–reperfusion.

In the present study, using tension myography and biochemical and histological techniques, we investigated the effects of chronic (2 months) low-dose nicorandil (0.1 mg/kg per day) treatment on the function of rat aorta during ageing (in 4-, 12- and 24-month old rats).

The results showed that chronic nicorandil treatment significantly improves mechanical relaxation and noradrenaline-induced vasoconstriction in aged rats. At all ages, the nicorandil-induced vasodilation was primarily mediated by its NO donor group. Nicorandil treatment resulted in an additional 0.5–1 elastic lamella in the aorta and decreased total protein, collagen and elastin content in the aortic wall at all ages. However, in 4-month-old rats, nicorandil significantly increased the elastin : total protein ratio by 19%.

In contrast with results of previous studies that used high doses of nicorandil (i.e. 60 mg/kg per day), low-dose nicorandil treatment in the present study did not lead to a progressive desensitization to nicorandil and may be beneficial in improving arterial function in ageing or cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: ageing, arterial mechanics, arteries, ATP-dependent potassium channels, cardiovascular system, collagen, elastic fibres, elastin, nicorandil, vasoactivity

INTRODUCTION

Ageing large arteries remodel, classically exhibiting accelerated endothelial cell turnover, smooth muscle cell hypertrophy, increased diameter and wall thickness, as well as elastic fibre fragmentation and collagen accumulation. These events progressively lead to wall stiffening and increases in blood pressure.1 Large arteries of aged animals are also more contracted, although less responsive to vasoactive agents/pathways,2 such as noradrenaline/α-adrenoceptors,3–6 acetylcholine (ACh)/nitric oxide (NO)7,8 or membrane K+ channel opening. The latter mechanism blocks voltage-dependent membrane calcium channels and induces vasodilation9 and partly mediates ACh-induced vasodilation.10,11 The ATP-dependent K+ (KATP) channels have the additional role of cell metabolism sensors.12 The function of KATP channels from different cell types is progressively altered because of an age-dependent oxidation of thiol groups from the intracellular portion of the channel.13 This oxidation inhibits both the spontaneous and agonist-triggered activities of the channels,13 leading to age-dependent decreases in arterial reactivity to different vasoregulatory molecules, including catecholamines and ACh.14,15

Because K+ channel dysfunction contributes substantially to the age-dependent arterial dysfunctions described above,14,15 many studies have investigated the relevance of treatments whose purpose was to restore the responsiveness of K+ channels, in particular KATP channels, in ageing or cardiovascular diseases.16–19 Nicorandil (N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-nicotinamide nitrate) is a drug of choice in these treatments because its combined molecular structure and function targets several deleterious mechanisms involved in arterial ageing, namely KATP channel oxidation and dysfunction and NO pathway impairment. Nicorandil is a KATP channel opener molecule combining an organic nitrate and a nicotinamide group, which confer the additional properties of an NO donor and anti-oxidant, respectively.18,20 Acute low doses of nicorandil (range 10 μg/kg to 1 mg/kg) have been shown to lower blood pressure, reduce oxidized KATP channels and restore their activity,21 induce dilation of different types of arteries through NO delivery and KATP channel opening22,23 and improve the global condition of patients with angina pectoris.24 Acute higher doses of nicorandil (25–100 μg/kg) in a cardiac infarction model in rats have been shown to result in decreased formation of microvascular obstruction and a reduction in infarct size.25 In humans with cardiac infarction, acute nicorandil has been shown recently to suppress the infarction-induced increase in plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase activity and to prevent left ventricular remodelling.26 However, chronic treatment with high doses of nicorandil (60 mg/kg per day) produces opposite effects in the long term (i.e. 2–4 weeks), namely desensitization of KATP channels to agonists and inactivation of the cGMP pathway/vascular smooth muscle cell relaxation.17 Previously, we showed that chronic treatment of rats with a low dose of nicorandil (0.1 mg/kg per day for 2 months) improved cardiac function in ageing, under both physiological and experimentally induced pathological conditions. Heart function (developed pressure, action potential duration, survival rate) was protected during ageing and ischaemia–reperfusion experiments because of a higher activity of KATP channels.27

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of chronic treatment with a low dose of nicorandil on arterial structure and function during ageing in rats. The results show that low-dose nicorandil treatment induces aortic remodelling and improves function in aged animals.

METHODS

Animal treatment

Female Wistar rats, aged 2 months (n = 25), 10 months (n = 32) and 22 months (n = 21), were obtained from Charles River (L’Arbresle, France). Rats were divided into untreated (control) and nicorandil-treated groups. In order to equalize the average hormonal status in treated and control groups so that a potential interaction between female hormones and treatment equally affected control and treated groups, rats were randomly distributed in both groups. Nicorandil (0.1 mg/kg per day) was mixed with a small amount of food, placed in a container. The container was left in the cage for a few hours until it was emptied of food. The mixture was given at 0900 hours each day for the 2 months preceding the measurements. After 2 months treatment, rats were killed and their organs harvested. At this point, the rats in the three different age groups were were 4-, 12- and 24-months old. The housing of rats and the surgical procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Preparation of aortic ring segments and perfusion conditions

Rats were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). The descending thoracic aorta was excised and placed in an oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Krebs’ bicarbonate buffer (Kb) containing (in mmol/L): NaCl 118; KCl 5.6; CaCl2 2.4; MgCl2 1.2; KH2PO4 1.2; NaHCO3 20; D-Glucose 11 (pH 7.4). The tissue was cleaned of adherent connective tissue and fat before being cut into 1–2 mm transverse segments. Aortic rings were placed horizontally between a stationary stainless-steel hook and a mobile hook attached to an isometric force transducer (Biologic, Claix, France) connected to a microcomputer. A peristaltic pump continuously delivered the medium (1.5 mL/min; 37°C) to the organ bath (0.9 mL). A mechanical tension of 1.5 g was applied for 60 min and was readjusted back to 1.5 g every 15 min for 75 min before experiments were started. Aortic rings were precontracted and perifused until the end of the experiment with Kb containing 10−6 mol/L noradrenaline (KbNA), which induced approximately 80% of the maximal tension developed by noradrenaline (NA). The integrity of the endothelium was confirmed by the addition of 10−6 mol/L ACh to the KbNA before recontracting rings with KbNA alone. Rings were then perifused with KbNA alone (control) or KbNA supplemented with nicorandil (25 μmol/L) or SG-86 (25 μmol/L), a nicorandil molecule in which the NO2 group has been removed. For this reason, SG-86 is not an NO donor. Some rings were perifused for 15 min with nicorandil in the absence or presence of inhibitors, specifically 3 μmol/L glibenclamide, a KATP channel blocker, or 1 μmol/L 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), a guanylate cyclase blocker. Mechanical relaxation, measured for all rings, is defined as the spontaneous decrease in ring tension over time (first 15 min) after an initial mechanical tension of 1.5 g had been applied.

Protein content of the vascular wall

Aortic segments were harvested and their length measured under a microscope. Samples were hydrolysed in 6 mol/L HCl for 24 h at 107°C, evaporated to dryness and resuspended in 1 mL water. Desmosine levels, considered to be representative of elastin content, were determined by radioimmunoassay as described previously.28 Hydroxyproline levels, considered an index of collagen content, were determined by amino acid analysis using standard techniques.29 Total protein was determined in the same hydrolysate using the same ninhydrin-based method, in which the levels of all amino acids were quantified before summation, giving total protein content. Results are expressed as amino acid mass per vessel length unit or as protein content ratios.

Histology

Thoracic descending aortas excised from anaesthetized rats were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding. Haematoxylin–eosin and, for elastic fibres, Weigert staining were performed on transverse sections of the vessels. The number of elastic lamellae, cell density, luminal diameter and wall thickness were counted and/or measured.

Drugs and materials

The following drugs and reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Quentin Fallavier, France): components for the Krebs’ bicarbonate solution, NA, ACh, glibenclamide and ODQ. Nicorandil was a generous gift from Merck-Lipha (Lyon, France) and SG-86 was a generous gift from Central Research Laboratories (Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan).

Data analysis

Vasomotricity results are expressed as the mean±SEM of aortic ring tension (in g or mg) 15 min after application of each agent. For analysis of the effects of nicorandil, SG-86, glibenclamide and ODQ, the initial tension of each aorta ring was normalized against the average value of NA-induced precontraction in untreated 4-month-old rats (1160 mg). Statistical analysis of the ring tension, number of elastic lamellae, wall thickness, cell density, luminal diameter, total protein and desmosine and hydroxyproline content of the arterial wall, as well as protein ratios, was performed using two- or three-way ANOVA to compare results obtained in the presence or absence of the substances tested. Statistical tests were completed, when necessary, by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test for paired value comparisons. Unless indicated otherwise, all differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Mechanical relaxation of aortic rings

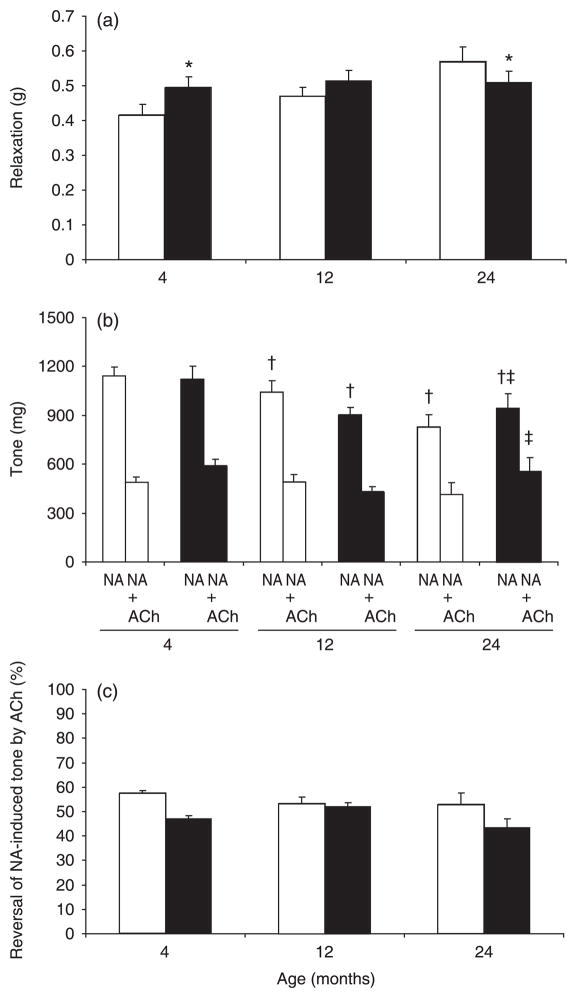

The mechanical relaxation of aortic rings was generally increased in ageing, in both untreated and nicorandil-treated rats. However, in nicorandil-treated rats, age-dependent enhancement of vasorelaxation was lower than in untreated rats. When compared with age-matched untreated rats, nicorandil treatment significantly modified the spontaneous mechanical relaxation of aortic rings, except in 12-month-old rats. In aortic rings from 4-month-old rats, nicorandil treatment increased aortic relaxation, whereas in rings from 24-month-old rats nicorandil treatment decreased aortic relaxation to values seen in 12-month-old nicorandil-treated rats (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Mechanical relaxation and reactivity of aortic rings as a function of age and chronic nicorandil treatment. (□), control (untreated); (■), chronic low-dose nicorandil (0.1 mg/kg per day) treatment for 2 months. (a) Loss in ring tension 15 min after application of the initial mechanical tension of 1.5 g. (b, c) Tone of rat aortic rings in response to noradrenaline (NA) and acetylcholine (ACh) as a function of age and chronic nicorandil treatment. Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 8–15). *P < 0.05 compared with age-matched control; †P < 0.05 compared with 4-month-old rats in the same treatment group; ‡P < 0.05 compared with age-matched control in the presence of the same agonist.

Response of aortic rings to reference vasoactive agents

Aorta ring responses to NA and ACh decreased with ageing, independent of treatment. A general age-dependent decrease in NA-induced ring tension (Fig. 1b) and a decrease in reversal of NA-induced tension by ACh were observed (Fig. 1b, c). However, in 24-month-old rats only, chronic treatment with nicorandil improved aortic responses to NA (+15%) compared with responses in age-matched untreated rats. Consequently, although a substantial decrease in response to NA was observed between 12 and 24 months in untreated rats, no change was observed over the same period in nicorandil-treated rats (Fig. 1b). It also appeared that chronic nicorandil treatment generally decreased ring vasodilatory responses to ACh independent of age (P = 0.05, two-way ANOVA; Fig. 1c), possibly in relation with the 15% increase in response to NA induced by nicorandil.

Response of aortic rings to acute application of nicorandil or SG-86

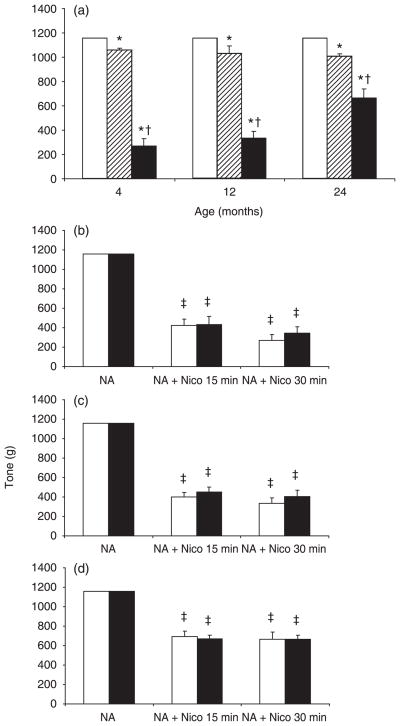

In control rats, acute SG-86 (25 μmol/L) produced a limited vasodilator response of 8.5, 11 and 13% in 4-, 12- and 24-month-old rats, respectively. The vasodilator response of aortic rings to 25 μmol/L nicorandil in the presence of SG-86 was greater, but decreased with age (77, 71 and 43% in aortic rings from 4-, 12- and 24-month-old rats, respectively; Fig. 2a). Chronic nicorandil treatment of rats at all ages had no significant effect on the strong vasodilator response to acute nicorandil compared with responses of aortic rings from age-matched untreated rats (Fig. 2b–d).

Fig. 2.

Vasodilator effects of nicorandil and SG-86 on aortic rings as a function of age. (a) Effect of acute application of 25 μmol/L SG-86 alone (▨) or with 25 μmol/L nicorandil (■) for 30 min on 1 μmol/L NA-precontracted rings from untreated rats. Initial NA-induced tone (□) was normalized to 1160 mg. (b–d) Effects of acute nicorandil (Nico) on aortic tone of untreated (□) and chronic nicorandil-treated (■) 4- (b), 12- (c) and 24-month-old (d) rats. Aortic rings were precontracted with 1 μmol/L noradrenaline (NA). Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 4–12). *P < 0.05 compared with age-matched control; †P < 0.05 compared with age-matched SG-86-treated group. ‡P < 0.05 compared with NA-induced tension in age-matched rats in the same treatment group.

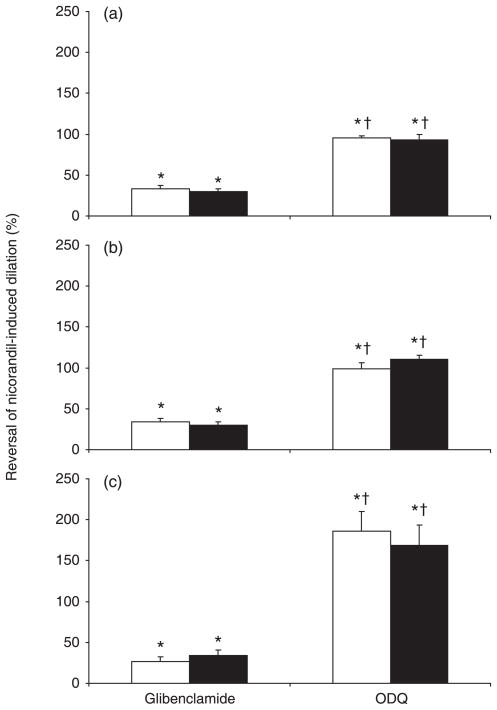

The effects of glibenclamide and ODQ on arterial responses to acute nicorandil were investigated. The acute nicorandil-induced vasorelaxation was partially reversed by glibenclamide (by approximately 30–35%) and completely abolished by ODQ in vessels from chronic nicorandil-untreated rats (Fig. 3). In 24-month-old rats, ODQ reversed the effect of nicorandil to more than 100%, suggesting an important contribution of the cGMP pathway to basal vascular tone in aged animals. In all age groups, the effects of glibenclamide and ODQ on vasodilator responses to acute nicorandil were not affected by chronic nicorandil treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of glibenclamide and 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) on the vasodilation induced by acute nicorandil as a function of age and chronic nicorandil treatment. (□), control (untreated); (■), chronic low-dose nicorandil (0.1 mg/kg per day) treatment for 2 months. Aortic rings were precontracted with 1 μmol/L noradrenaline before the acute application of 25 μmol/L nicorandil (30 min), followed by the addition of 3 μmol/L glibenclamide or 1 μmol/L ODQ. Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 9–11). *P < 0.05 compared with NA + acute nicorandil in the same treatment group; †P < 0.05 compared with glibenclamide.

Total protein, elastin and collagen content in aortic wall

Total protein, desmosine and hydroxyproline content generally increased with age in all groups (P ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA). In contrast, when chronic nicorandil-treated rats were compared with age-matched untreated rats, total protein, desmosine and hydroxyproline content was generally decreased in all age groups (P ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA). However, when the ratios of desmosine or hydroxyproline to total protein were examined, chronic nicorandil treatment produced a significant increase in these ratios in 4-month-old rats only, indicating a change in matrix composition (i.e. an increase in the proportion of these molecules in the arterial wall of young animals). The desmosine : hydroxyproline ratio, an index of the elastin : collagen ratio, was decreased only in 4-month-old rat chronically treated with nicorandil (P ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA; Table 1).

Table 1.

Total protein, desmosine and hydroxyproline content in the descending thoracic aorta of 4-, 12- and 24-month old rats untreated or treated chronically (for 2 months) with nicorandil

| Control | Nicorandil | |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein (μg/mm) | ||

| 4 month old | 159 ± 9* | 108 ± 14*† |

| 12 month old | 191 ± 16* | 178 ± 17*† |

| 24 month old | 244 ± 21* | 207 ± 34*† |

| Desmosine (μg/mm) | ||

| 4 month old | 0.75 ± 0.10* | 0.55 ± 0.08*† |

| 12 month old | 0.83 ± 0.11* | 0.90 ± 0.09*† |

| 24 month old | 0.93 ± 0.08* | 0.86 ± 0.15*† |

| Hydroxyproline (μg/mm) | ||

| 4 month old | 3.07 ± 0.31* | 2.61 ± 0.29*† |

| 12 month old | 4.99 ± 0.70* | 4.52 ± 0.61*† |

| 24 month old | 6.40 ± 0.78* | 5.96 ± 1.51*† |

| Desmosine : total protein (%) | ||

| 4 month old | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.11‡ |

| 12 month old | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.02 |

| 24 month old | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.03 |

| Hydroxyproline : total protein (%) | ||

| 4 month old | 1.96 ± 0.20 | 2.82 ± 0.47‡ |

| 12 month old | 2.52 ± 0.15 | 2.35 ± 0.20 |

| 24 month old | 2.45 ± 0.16 | 2.53 ± 0.24 |

| Desmosine : hydroxyproline (%) | ||

| 4 month old | 25.9 ± 4.7 | 18.5 ± 0.8‡ |

| 12 month old | 17.2 ± 0.7 | 17.6 ± 0.4 |

| 24 month old | 15.4 ± 1.0 | 15.5 ± 1.2 |

Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 3–4 in each group).

Significant (P < 0.05) effect of age, independent of nicorandil treatment.

Generally significant (P < 0.05) change induced by chronic nicorandil treatment compared with untreated animals (control), independent of age.

Significant (P < 0.05) change induced by chronic nicorandil treatment compared with age-matched controls.

Aortic wall thickness and the number of elastic lamellae and cells

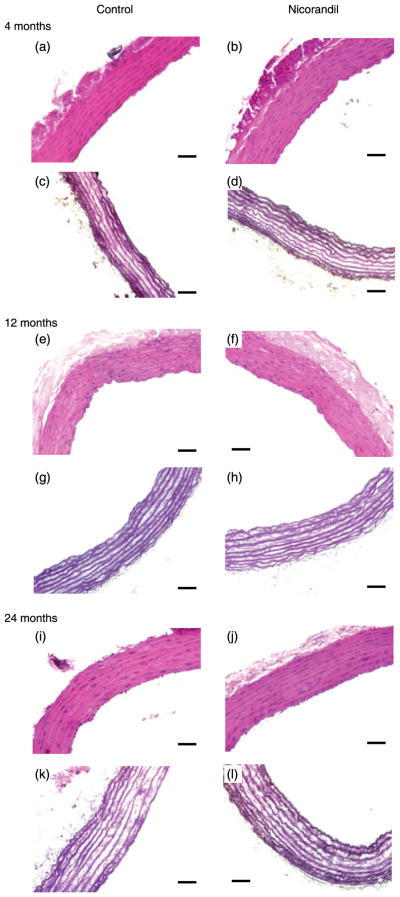

The number of elastic lamellae in the media of the aortic wall was unchanged by ageing, but was increased significantly by chronic nicorandil treatment in all age groups (P ≤ 0.05, two-way ANOVA). One supplementary lamella in 4-month-old rats and half an additional lamella in 12- and 24-month-old rats were observed following chronic nicorandil treatment (Fig. 4; Table 2). Ageing also resulted in a decrease in wall cell density and an increase in aortic wall thickness and luminal diameter in all groups, independent of nicorandil treatment (P ≤ 0.05, two- and three-way ANOVA, respectively). Chronic nicorandil treatment had no effect on these last three parameters in rats at any age (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Histological examination of the ascending aorta as a function of age and chronic nicorandil treatment. Paraffin-embedded cross-sections of descending thoracic aortas from 4- (a–d), 12- (e–h) and 24-month-old (i–l) rats untreated or treated chronically with nicorandil were stained with haematoxylin–eosin (a, b, e, f, i, j) or Weigert (c, d, g, h, k, l). Bars, 50 μm. A representative image is shown for each group (n = 3–4 in each group).

Table 2.

Number of elastic lamellae, cell density, luminal diameter and wall thickness in the descending thoracic aorta of 4-, 12- and 24-month old rats untreated or treated chronically (for 2 months) with nicorandil

| Control | Nicorandil | |

|---|---|---|

| No. lamellae | ||

| 4 month old | 8.1 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.1* |

| 12 month old | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.8 ± 0.2* |

| 24 month old | 8.0 ± 0.0 | 8.5 ± 0.3* |

| Cell density (cells/mm2) | ||

| 4 month old | 2140 ± 150† | 2112 ± 48† |

| 12 month old | 1697 ± 64† | 1463 ± 76† |

| 24 month old | 1415 ± 91† | 1487 ± 193† |

| Luminal diameter (μm) | ||

| 4 month old | 1500 ± 30† | 1482 ± 47† |

| 12 month old | 1511 ± 28† | 1505 ± 24† |

| 24 month old | 1600 ± 50† | 1521 ± 75† |

| Wall thickness (μm) | ||

| 4 month old | 88 ± 9† | 92 ± 5† |

| 12 month old | 101 ± 10† | 99 ± 3† |

| 24 month old | 123 ± 3† | 131 ± 5† |

Data are the mean±SEM (n = 3–4 in each group).

P < 0.05 compared with control, independent of age.

General significant (P < 0.05) effect of age, independent of nicorandil treatment.

No significant effects of chronic nicorandil treatment were found on cell density, luminal diameter and wall thickness.

DISCUSSION

In nicorandil-treated rats, but not in untreated rats, the aorta maintained its ability to resist mechanical extension with ageing, suggesting that nicorandil increases myogenic tone in aged vessels. In addition, nicorandil treatment improved the contractile response of aged aortic rings to NA, possibly because of reversal of the classically described decreased quantity and responsiveness of certain α1-adrenoceptor subtypes during ageing3–6,30,31 and/or activation by nicorandil/NO of the cGMP and KATP channel opening pathways, which would enhance calcium levels in intracellular stores and reduce calcium influx and basal intracellular calcium concentrations.11,32–35 The latter mechanisms could improve the ability of aged vascular smooth muscle cells to mobilize calcium and contract when stimulated by NA.

Consistent with the literature,36 the acute vasodilatory effect of nicorandil in the present study was due mainly to NO release and less to KATP channel opening because SG-86 elicited a vasodilation of much lower amplitude. This was confirmed by the significant inhibition of the nicorandil-induced vasodilation by a guanylate cyclase blocker. However, the low response of NA-precontracted aortic rings to SG-86 could be explained, in part, by the inhibition of KATP channels by NA via its action on protein kinase C.37 Moreover, no desensitization to nicorandil following low-dose nicorandil treatment was observed, either in terms of the vasodilator response or guanylate cyclase activity,23 as opposed to the effect of chronic treatment with high-dose nicorandil or other nitrated products.17,38 An additional anti-oxidant effect of nicorandil to improve arterial reactivity should not be discounted. Ageing induces KATP channel oxidization and subsequent dysfunction of cardiovascular cells,14,15,39,40 which can be inhibited by anti-oxidant treatments, including nicorandil.18,41–44

Whereas ageing induced a general increase in total proteins, desmosine and hydroxyproline content, chronic nicorandil treatment generally decreased levels of total proteins, desmosine and hydroxyproline at all ages studied. This could be due to the decrease in blood pressure induced by nicorandil, in accordance with the lowered arterial collagen and/or elastin content observed previously during a drop in blood pressure.45,46 This is supported by the lower decrease in protein content observed in 12-month-old rats, the only age at which the nicorandil-induced blood pressure decrease was not significant.27 However, nicorandil treatment induced a higher decrease in total protein than in desmosine and hydroxyproline content in 4-month-old rats (i.e. the proportion of elastin and collagen was increased in the extracellular matrix of these young, nicorandil-treated rats). This suggests that the greatest efficiency of nicorandil treatment in terms of aortic wall remodelling is when elastin synthesis is still relatively active (before 4 months of age). Furthermore, additional elastic lamellae appeared after nicorandil treatment: one more elastic lamella in 4-month-old rats and half a lamella in 12- and 24-month-old rats. This potentially contributed to maintenance of the mechanical characteristics of aged aortas closer to these of young animals. These results suggest that nicorandil induces a general decrease in aortic wall protein content, potentially related to decreased blood pressure, and a more specific positive effect on elastin neosynthesis and elastic fibre assembly. The latter resembles the induction of elastin synthesis by another KATP channel opener, namely minoxidil, in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells and in vivo,47–49 raising the question of a more general effect of potassium metabolism in the regulation of elastin synthesis, which is linked to K+ channel and Na+/K+-ATPase gene expression.50

In conclusion, low-dose nicorandil treatment limited or abolished some age-dependent changes in arterial function and increased the number of elastic lamellae in the aortic wall; however, it did not lead to long-term desensitization. These results suggest that the use of chronic low-dose nicorandil treatment may be of interest in future preclinical and clinical trials aimed at preventing or treating cardiovascular dysfunction related to ageing or heart disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Région Rhône-Alpes (France) to SR. The authors acknowledge the European Commission for funding: contracts TELASTAR, 5th PCRD, no. QLK6-CT-2001–00332; and ELAST-AGE, 6th PCRD, no. LSHM-CT-2005-018960.

References

- 1.Robert L. Le Vieillissement. CNRS–Belin; Paris: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cernadas MR, Sanchez de Miguel L, Garcia-Duran M, et al. Expression of constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthases in the vascular wall of young and aging rats. Circ Res. 1998;83:279–86. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Docherty JR. The effects of ageing on vascular alpha-adrenoceptors in pithed rat and rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;146:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90480-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson MD, Wray A. Alpha 1 adrenergic receptor function in senescent Fischer 344 rat aorta. Life Sci. 1990;46:359–66. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90015-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vila E, Vivas NM, Tabernero A, Giraldo J, Arribas SM. Alpha1-adrenoceptor vasoconstriction in the tail artery during ageing. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1017–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto M, Gamoh S, Hossain S, et al. Age-related changes in aortic sensitivity to noradrenaline and acetylcholine in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:676–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donoso MV, Fournier A, Peschke H, Faúndez H, Domenech R, Huidobro-Toro JP. Aging differentially modifies arterial sensitivity to endothelin-1 and 5-hydroxytryptamine: Studies in dog coronary arteries and rat arterial mesenteric bed. Peptides. 1994;15:1489–95. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llorens S, Fernandez AP, Nava E. Cardiovascular and renal alterations on the nitric oxide pathway in spontaneous hypertension and ageing. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2007;37:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Standen NB. The GL Brown Lecture. Potassium channels, metabolism and muscle. Exp Physiol. 1992;77:1–25. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1992.sp003564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satake N, Shibata M, Shibata S. The involvement of KCa, KATP, and KV channels in vasorelaxing responses to acetylcholine in rat aortic rings. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:453–7. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miki T, Seino S. Roles of KATP channels as metabolic sensors in acute metabolic changes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:917–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricarico D, Conte Camerino D. ATP-sensitive K+ channels of skeletal muscle fibers from young adult and aged rats. Possible involvement of thiol-dependent redox mechanisms in the age-related modifications of their biophysical and pharmacological properties. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:754–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Martinez MA, Alonso MJ, Redondo J, Salaices M, Marin J. Role of lipid peroxidation and the glutathione-dependent antioxidant system in the impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxations with age. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:113–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsujimoto G, Lee CH, Hoffman BB. Age-related decrease in beta adrenergic receptor-mediated vascular smooth muscle relaxation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;239:411–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner G. Selected issues from an overview on nicorandil: Tolerance, duration of action, and long-term efficacy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trongvanichnam K, Mitsui-Saito M, Ozaki H, Karaki H. Effects of chronic oral administration of a high dose of nicorandil on in vitro contractility of rat arterial smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mano T, Shinohara R, Nagasaka A, et al. Scavenging effect of nicorandil on free radicals and lipid peroxide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Metabolism. 2000;49:427–31. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollesello P, Mebazaa A. ATP-dependent potassium channels as a key target for the treatment of myocardial and vascular dysfunction. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:436–41. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000145099.20822.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taira N. Nicorandil as a hybrid between nitrates and potassium channel activators. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:J18–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanagisawa T, Satoh K, Taira N. Circumstantial evidence for increased potassium conductance of membrane of cardiac muscle by 2-nicotin-amidoethyl nitrate (SG-75) Jpn J Pharmacol. 1979;29:687–94. doi: 10.1254/jjp.29.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreye VT, Lenz A, Pfrunder D, Theiss U. Pharmacological characterization of nicorandil by 86Rbefflux and isometric vasorelaxation studies in vascular smooth muscle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20(Suppl 3):S8–12. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199206203-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kukovetz WR, Holzmann S, Poch G. Molecular mechanism of action of nicorandil. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20 (Suppl 3):S1–7. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199206203-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shetty K. Prescribing for angina. Practitioner. 1994;238:540–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krombach GA, Higgins CB, Chujo M, Saeed M. Gadomer-enhanced MR imaging in the detection of microvascular obstruction: Alleviation with nicorandil therapy. Radiology. 2005;236:510–18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362030847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiwara T, Matsunaga T, Kameda K, et al. Nicorandil suppresses the increases in plasma level of matrix metalloproteinase activity and attenuates left ventricular remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2007;22:303–9. doi: 10.1007/s00380-007-0975-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garnier-Raveaud S, Faury G, Mazenot C, Cand F, Godin-Ribuot D, Verdetti J. Highly protective effects of chronic oral administration of nicorandil on the heart of ageing rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:441–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starcher B, Conrad M. A role for neutrophil elastase in the progression of solar elastosis. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;31:133–40. doi: 10.3109/03008209509028401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown-Augsburger P, Tisdale C, Broekelmann T, Sloan C, Mecham RP. Identification of an elastin cross-linking domain that joins three peptide chains. Possible role in nucleated assembly. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17, 778–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurdal H, Tilakaratne N, Brown RD, Fonseca M, Friedman E, Johnson MD. The expression of alpha1 adrenoceptor subtypes changes with age in the rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1656–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faury G, Chabaud A, Ristori MT, Robert L, Verdetti J. Effect of age on the vasodilatory action of elastin peptides. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;95:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taguchi K, Ueda M, Kubo T. Effects of cAMP and cGMP on L-type calcium channel currents in rat mesenteric artery cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1997;74:179–86. doi: 10.1254/jjp.74.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstead WM. Relationship among NO, the KATP channel, and opioids in hypoxic pial artery dilation. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H988–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cogolludo AL, Perez-Vizcaino F, Fajardo S, Ibarra M, Tamargo J. Effects of nicorandil as compared to mixtures of sodium nitroprusside and levcromakalim in isolated rat aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1025–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen SJ, Wu CC, Yang SN, Lin CI, Yen MH. Abnormal activation of K+ channels in aortic smooth muscle of rats with endotoxic shock: Electrophysiological and functional evidence. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:213–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berdeaux A, Drieu la Rochelle C, Richard V, Giudicelli JF. Differential effects of nitrovasodilators, K+-channel openers, and nicorandil on large and small coronary arteries in conscious dogs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20 (Suppl 3):S17–21. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199206203-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Standen NB, Quayle JM. K+ channel modulation in arterial smooth muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:557–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flaherty JT. Nitrate tolerance. A review of the evidence Drugs. 1989;37:523–50. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198937040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coetzee WA, Nakamura TY, Faivre JF. Effects of thiol-modifying agents on KATP channels in guinea pig ventricular cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1625–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dröge W. Aging-related changes in the thiol/disulfide redox state: Implications for the use of thiol antioxidants. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:1333–45. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Besse S, Bulteau AL, Boucher F, Riou B, Swynghedauw B, de Leiris J. Antioxidant treatment prevents cardiac protein oxidation after ischemia–reperfusion and improves myocardial function and coronary perfusion in senescent hearts. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57:541–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu C, Minatoguchi S, Arai M, et al. Nicorandil improves post-ischemic myocardial dysfunction in association with opening the mitochondrial K(ATP) channels and decreasing hydroxyl radicals in isolated rat hearts. Circ J. 2006;70:1650–4. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozcan C, Terzic A, Bienengraeber M. Effective pharmacotherapy against oxidative injury. Alternative utility of an ATP-sensitive potassium channel opener. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:411–18. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31812378df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raveaud S, Verdetti J, Faury G. Nicorandil protects ATP-sensitive potassium channels against oxidation-induced dysfunction in cardiomyocytes of aging rats. Biogerontology. 2008;9 doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9196-9. Epub 16 November 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safar ME, Levy BI, London GM. Arterial structure in hypertension and the effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition. J Hypertens. 1992;10 (Suppl 5):S51–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199207005-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayer IM, Adamson SL, Langille BL. Atrophic remodeling of the artery-cuffed artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1499–505. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.6.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi A, Suzuki T, Wachi H, et al. Minoxidil stimulates elastin expression in aortic smooth muscle cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;315:137–41. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tajima S. Modulation of elastin expression and cell proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Keio J Med. 1996;45:58–62. doi: 10.2302/kjm.45.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsoporis J, Keeley FW, Lee RMKW, Leenen FHH. Arterial vasodilatation and vascular connective tissue changes in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;31:960–2. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199806000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gauguier D, Behmoaras J, Argoud K, et al. Chromosomal mapping of quantitative trait loci controlling elastin content in rat aorta. Hypertension. 2005;45:460–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000155213.83719.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]