ABSTRACT

We wished to determine whether magnetic resonance imaging signs suggesting elevated intracranial pressure are more frequently found in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) than in those with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Among 240 patients who underwent standardised contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance brain imaging and venography at our institution between September 2009 and September 2011, 60 with abnormal imaging findings on magnetic resonance venography were included: 27 patients with definite and 2 patients with presumed idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and 31 with definite cerebral venous thrombosis. Medical records were reviewed, and imaging studies were prospectively evaluated by the same neuroradiologist to assess for presence or absence of transverse sinus stenosis, site of cerebral venous thrombosis if present, posterior globe flattening, optic nerve sheath dilation/tortuosity, and the size/appearance of the sella turcica. Twenty-nine patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (28 women, 19 black, median age: 28, median body mass index: 34 kg/m2) had bilateral transverse sinus stenosis. Thirty-one CVT patients (19 women, 13 black, median age: 46, median body mass index: 29) had thrombosis of the sagittal (3), sigmoid (3), cavernous (1), unilateral transverse (7), or multiple (16) sinuses or cortical veins (1). Empty/partially empty sellae were more common in IIH (3/29 and 24/29) than in cerebral venous thrombosis patients (1/31 and 19/31) (p < 0.001). Flattening of the globes and dilation/tortuosity of the optic nerve sheaths were more common in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (20/29 and 18/29) than in cerebral venous thrombosis (13/31 and 5/31) (p < 0.04). We conclude that although abnormal imaging findings suggestive of raised intracranial pressure are more common in IIH, they are not specific for that disorder and are found in patients with raised intracranial pressure from other causes such as cerebral venous thrombosis.

Keywords: Cerebral venous thrombosis, empty sella, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, MRI, MRV, venous hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, numerous publications have emphasised the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings seen in patients with increased intracranial pressure (ICP).1–3 Empty sella turcica has been described as a classic sign of chronically elevated ICP.3–8 Additionally, transverse sinus stenosis (TSS),9,10 optic disc protrusion11 flattening of the posterior globes,2,6 and prominence of the perioptic nerve cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces2,12–15 are also commonly reported in patients with increased ICP, particularly those with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). However, none of these signs are pathognomonic of IIH,16,17 and all have even been described in presumed normal subjects.9

Although the exact role of TSS in IIH patients remains unclear, bilateral TSS likely causes elevated intracranial venous pressure, which presumably contributes to decreased CSF absorption and subsequent increased ICP.18 Similar venous hemodynamic changes commonly occur in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), explaining why increased ICP is a common clinical feature of CVT.17 Indeed, CVT can mimic IIH clinically,17,19 and CVT needs to be ruled out in order to diagnose IIH, especially in patients with isolated papilloedema.20 The aim of our study was to compare the MRI findings of patients with IIH and bilateral TSS with those of patients with CVT. We hypothesised that if these presumed signs of elevated ICP are preferentially found in either group, this could further aid the differentiation of these two disorders of venous hypertension.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed all medical records of patients who underwent standardised contrast-enhanced brain MRI combined with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance venography (MRV) at our institution from September 2009 to September 2011. We included all patients with IIH found to have bilateral TSS on MRV (group I) and those with CVT (group II). The study was approved by our institutional review board. Except for two patients who did not have a lumbar puncture, IIH was diagnosed according to the modified Dandy criteria20 papilloedema, symptoms of raised ICP, no other cause for raised ICP on brain MRI, no CVT on brain MRV, and normal CSF contents with elevated CSF opening pressure (≥25 cm H2O). The diagnosis of CVT was based on classic MRI and MRV findings.17,19,21 Demographic information was recorded, including age, gender, race, and body mass index (BMI). Presenting symptoms, including headaches, visual changes, altered mental status, and focal neurological symptoms and signs, were also recorded. Results of lumbar puncture, especially CSF opening pressure, were documented.

All patients had brain imaging performed at the time of initial diagnosis. MRI was performed using a standardised protocol at either 3.0-Tesla (Siemens Trio, Erlangen, Germany) or 1.5-Tesla (Siemens Avanto, Erlangen, Germany, or GE Signa, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using a standard head coil. All patients underwent contrast-enhanced MRI along with contrast-enhanced MRV. The MRI/MRV protocol included routine pre-contrast axial diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), T1 weighted imaging (T1WI), T2 weighted gradient echo (T2W GRE), and sagittal T1WI. An axial pre-contrast MRV mask was obtained (TR of 4–6 ms, TE of 1–2 ms, and flip angle of 22—30 degrees with slice thickness of 0.8–1.4 mm). A standard dose (0.1 mmol/kg) of intravenous gadolinium-based contrast agent (Multihance, Bracco Diagnostics Inc., Princeton, New Jersey) was administered at 2.0 cc/second, and the axial MRV sequence was repeated 60 seconds following contrast administration. Post-contrast axial T1WI and sagittal volumetric T1WI GRE images of the brain were then acquired. The pre-contrast MRV data set was subtracted from the post-contrast data set, and multiple oblique maximum intensity projections (MIPs) were generated from this subtracted data set with rotation around the cranio-caudal axis (“spin”) or the transverse axis (“nod”) at 6-degree increments. Because the image matrix and field of view were standard at both field strengths (1.5 and 3 Tesla), the image resolution was the same and the field strength did not affect our results.

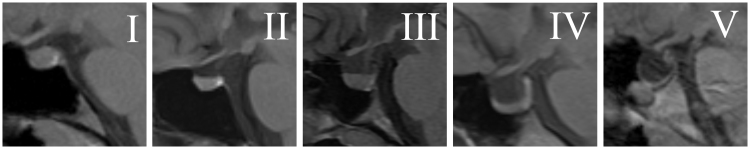

All MRIs and MRVs were reviewed by an experienced neuroradiologist (A.M.S.) and a neuro-ophthalmologist (M.A.R.). Pituitary tissue height on the sagittal T1WI was classified into five categories based on the system of Yuh et al.,7 with Grade I being normal and Grade V showing no visible pituitary tissue (Figure 1). The following measurements were recorded based on mid-sagittal T1WI: estimated anteroposterior (AP) length of the diaphragm sella (mm), maximum sellar AP dimension (mm), maximum cranio-caudal (CC) sellar dimension (mm), AP distance from the anterior diaphragm sella to pituitary stalk (mm), and CC distance of optic chiasm from diaphragm sella (Figure 2). Each patient’s full set of images was also evaluated for the following imaging findings according to methods previously published by Agid et al.,2 prominence of perioptic nerve CSF, flattening of the posterior sclera, protrusion of the optic disc, and vertical tortuosity of the optic nerve (Figure 3). MRV source data and maximum intensity projection (MIP) images were evaluated for location and extent of any venous sinus stenosis and thrombosis. Thrombosis was identified on sagittal and axial T1 and T2WI and MRV as previously described.19,21 TSS was identified on reformatted MRV images by visually evaluating the width of each transverse sinus and classifying the sinus as “stenotic” or “normal” as previously described.9 Neither the neuroradiologist or the neuro-ophthalmologist were blinded to the clinical diagnosis (because the diagnosis of CVT was based on radiologic findings of CVT, and not just clinical findings, it was not possible for those reviewing the MRIs not to notice the CVT or the absence of CVT). However, the MRIs were reviewed in no specific order and the neuroradiologist and the neuro-ophthalmologist worked together to reach an agreement on all reviewed scans.

FIGURE 1 .

Classification of pituitary height and morphology (adapted from Yuh et al.7). Grades I (normal) to V (no visible pituitary) are shown on mid-sagittal T1-weighted MRI images through the sella turcica: Grade I = normal; Grade II = mild superior concavity (less than 1/3 of the height of the sella); Grade III = moderate concavity (between 1/3 and 2/3 of the height of the sella); Grade IV = severe concavity (more than 2/3 of the height of the sella); Grade V = no visible pituitary tissue.

FIGURE 2 .

Technique used to measure the size of the sella turcica, the infundibulum, and the optic chiasm. For each patient, the measurements were made on a magnified mid sagittal T1-weighted MRI image through the sellar region. 1 = estimated diaphragm sella anteroposterior distance; 2 = anteroposterior distance of the infundibulum along the diaphragm sella; 3 = maximum anteroposterior distance of the sella; 4 = maximum cranio-caudal distance of the sella; 5 = cranio-caudal distance of the optic chiasm.

FIGURE 3 .

MRI showing protrusion of the optic disc (A), flattening of the posterior sclera (B), increased CSF perioptic space (C), and vertical tortuosity of the optic nerve (D).

Statistical analysis was performed with R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing (http://www.R-project.org). Group I (IIH) with TSS was compared with group II (CVT). Means and standard deviations (± SD) are reported for continuous, normally distributed data, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are reported otherwise. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare frequency distributions. Two-sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U were used to compare continuous variables. Ordinal logistic regression with empty sella grade as the outcome and race, sex, age, BMI, and the diagnosis (IIH or CVT) as predictors was performed.

RESULTS

Among the 240 patients who underwent standardised contrast-enhanced brain MRI and contrast-enhanced MRV, 180 patients were excluded (140 with normal MRV, 30 with abnormal MRVs related to other pathologies than IIH or CVT, and 10 with incomplete data). The remaining 60 patients included 29 IIH patients with bilateral TSS (27 with definite IIH and 2 with presumed IIH) and 31 patients with CVT (15/31 CVT patients had multiple sinuses involved at the time of the MRV study, 7 CVT patients had unilateral TS thrombosis, 3 patients had sigmoid sinus thrombosis, 3 had superior sagittal sinus thrombosis, 1 had cavernous sinus thrombosis, and 2 had additional cortical vein thrombosis).

The differences between the IIH and CVT groups are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Black race was more frequent among IIH patients than CVT patients (66% vs. 42%, p = 0.07). Women represented nearly all of the IIH group (97% vs. 61%, p = 0.001). At initial evaluation, IIH patients were much more likely to report headaches (76% vs. 26%, p = 0.002), and, by inclusion criteria, all IIH patients had papilloedema. Only 12 patients with CVT (31%) had a documented funduscopic examination, with 6 of them (50%) noted to have papilloedema.

TABLE 1 .

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension with transverse venous stenosis and patients with cerebral venous thrombosis.

| II (N = 29) |

CVT (N = 31) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) or median [IQR] | n (%) or median [IQR] | p-value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 28 [22–38] | 46 [34–55] | 0.69 |

| Black | 19 (66%) | 13 (42%) | 0.07 |

| Female | 28 (97%) | 19 (61%) | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34 [30–41] | 29 [25–32] | 0.35 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Headaches | 22 (76%) | 8 (26%) | 0.002 |

| Papiloedema | 29 (100%) | 6/12 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Number of patients with funduscopic examination | 29 (100) | 12/31 | (31%) |

| Focal neurological symptoms | 0 (0%) | 15 (48%) | <0.001 |

| Number of patients with CSF OP | 27 (93%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Mean CSF OP (cm H2O) | 34 [30–42] | 32 [31–34] | 0.33 |

CVT = cerebral venous thrombosis; IIH = idiopathic intracranial hypertension; BMI = body mass index; IQR = interquartile range; OP = opening pressure.

TABLE 2 .

Radiologic characteristics of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension with transverse venous stenosis and patients with cerebral venous thrombosis.

| IIH (N = 29) |

CVT (N = 31) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) or mean in mm (SD) [range] | n (%) or mean in mm (SD) [range] | p-value |

| Sellar morphology | |||

| Diaphragm sella AP | 12 (2.1) [8–17] | 11 (1.8) [8–19] | 0.12 |

| AP stalk position | 9 (1.7) [6–12] | 8 (1.7) [6–13] | 0.03 |

| Maximum AP sella | 14 (2.4) [10–20] | 12 (1.7) [9–17] | 0.0001 |

| Maximum CC sella | 10 (2.3) [6–14] | 8 (1.8) [6–14] | 0.02 |

| Chiasm height | 3 (1.9) [3–5] | 3 (1.2) [1–6] | 0.31 |

| Pituitary grading | |||

| Grade I | 2 (7%) | 11 (36%) | 0.0004 |

| Grade II | 4 (14%) | 6 (19%) | |

| Grade III | 6 (21%) | 10 (32%) | |

| Grade IV | 14 (48%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Grade V | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Globe/orbit morphology | |||

| Increased perioptic CSF | 18 (62%) | 5 (16%) | 0.0002 |

| Scleral flattening | 20 (69%) | 13 (42%) | 0.04 |

| ON vertical tortuosity | 6 (21%) | 2 (6%) | 0.14 |

IIH = idiopathic intracranial hypertension; CVT = cerebral venous thrombosis; SD = standard deviation; AP = anteroposterior; CC = cranio-caudal; ON = optic nerve.

Lumbar puncture with CSF opening pressure measurement was performed in 27/29 IIH patients. Two patients with symptoms of raised ICP and papilloedema with normal visual function did not have a lumbar puncture, but had a typical course of IIH (with papilledoema resolving during follow-up), and therefore were included in this study. Seven of the 31 CVT patients had lumbar puncture, but a reliable CSF opening pressure value was available in only 3 patients. All patients who underwent lumbar puncture had elevated CSF opening pressure, and this was similar in the two groups.

All included IIH patients had bilateral TSS on MRV. Sixteen (52%) of the CVT patients had simultaneous involvement of multiple sinuses: 7 (23%) of a unilateral transverse sinus, 3 (10%) of the sigmoid sinus, 3 (10%) of the superior sagittal sinus, 1 (3%) of the cavernous sinus, and 1 (3%) of a cortical vein.

The dimensions of the sella turcica (except for the diaphragm sella AP measurement) were higher in the IIH group than in CVT patients (p < 0.02; Table 1). Empty and partially empty sellae were more common and more severe in the IIH patients than in the CVT patients (p = 0.0004). Increased perioptic nerve CSF space (62% vs. 16%) and scleral flattening (69% vs. 42%) were also both seen more commonly in IIH than CVT (p < 0.04). Ordinal logistic regression found that black patients had 5.48 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.96–15.33, p = 0.003) times the odds of one grade emptier sella compared to non-black patients, independent of the 4.75 (95% CI: 1.7–13.25, p = 0.001) times odds conveyed by the presence of IIH compared to CVT. Neither age, nor gender, nor BMI predicted the degree of empty sella, nor did they confound the relationship between race or IIH with empty sella.

DISCUSSION

It has long been recognised that IIH and CVT share many clinical and radiologic features. Although patients with IIH tend to be more often female and overweight than CVT patients, there is considerable clinical overlap between these two disorders. It has been previously emphasised that at least one-third of CVT patients present with a syndrome of isolated increased ICP (headaches and papilloedema) that is clinically undistinguishable from IIH.17 Therefore, the diagnosis of CVT in many patients relies exclusively on brain imaging. Despite major improvement in MRI techniques over the past decade, misinterpretation of brain MRI resulting in delayed diagnosis of CVT remains common, especially in patients presenting with isolated raised ICP. Imaging of the intracranial venous system with MRV is not systematically requested by most clinicians evaluating patients with a syndrome of isolated raised ICP, and radiologists are often asked to “rule out CVT” on an isolated brain MRI. Our study suggests that, in this setting, identification of imaging findings suggestive of raised ICP, such as sella turcica abnormalities, dilation of the optic nerve sheath, and flattening of the globe, may be helpful. Indeed, although MRI findings suggestive of raised ICP were present in both our IIH and the CVT groups, they were more common among IIH patients than those with CVT.

Thrombosis or stenosis of cerebral venous sinuses results in intracranial venous hypertension, which contributes to elevated ICP by reducing passive CSF resorption at the level of the arachnoid villi. Venous hypertension is very common in CVT patients and explains the classic clinical symptoms and signs of raised ICP such as headaches, papilloedema, and altered mental status often reported in CVT patients.17 The pathophysiology of IIH is unknown and remains largely debated1; however, the role of venous hypertension in IIH is well recognised, particularly in those IIH patients found to have TSS on brain MRV. Some authors have emphasised the role of venous hypertension as a “universal” mechanism underlying most syndromes of isolated increased ICP, including IIH and CVT.18 Although a few previous studies have compared the clinical and radiologic characteristics of IIH with those of CVT,8,18 our study is unique in that we only included IIH patients with evidence of intracranial venous stenosis on high-quality contrast-enhanced MRV. All our IIH patients had bilateral TSS, and therefore presumably had impaired venous drainage resulting in intracranial venous hypertension, perhaps similar to what is observed in patients with thrombosed venous sinuses. This makes our population of IIH patients more comparable to the CVT patients from a venous hemodynamic viewpoint.

Our two groups of patients had different clinical profiles, suggesting that our CVT patients might not have had raised ICP the way our IIH patients did. Indeed, only 8 of 31 CVT patients had headaches, and only 6 of 12 had papilloedema. The retrospective nature of our study is likely responsible for an underestimation of symptoms and signs of raised ICP, which are often not well documented when there are other serious neurological signs. Similarly, only 7 CVT patients even had lumbar punctures, and only 3 of those had documented opening pressure. However, we chose to include all CVT patients in this study, because the absence of papilloedema does not rule out disorders of ICP, and appearance of papilloedema might be delayed in patients with acute disorders such as CVT, making the radiologic findings even more important.

Our two groups of patients also had differences in the frequency of radiologic findings. Increased perioptic CSF, flattening of the globe, and empty sella were more commonly found in IIH patients than in CVT patients. It is likely that these MRI findings classically suggestive of raised ICP reflect chronically elevated ICP (such as in IIH) rather than acute or subacutely raised ICP (such as in CVT). Such findings are indeed often used by radiologists as an indicator of chronically raised ICP, and therefore might be suggestive of IIH in the appropriate clinical setting and in the absence of other MRI/MRV abnormalities. However, it is not known how long it takes for these radiologic changes to develop in the setting of raised ICP, and such MRI findings have also been described in normal subjects and in patients with headache syndromes not associated with increased ICP.9

As emphasised above, the main limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. However, only patients who had imaging studies performed at our institution with a specific standardised protocol were included. Therefore all images could be analysed in a similar fashion and directly compared with each other. The retrospective nature of the study made the clinical characterization of the patients difficult. Although all IIH patients had been examined by us in neuro-ophthalmology, this was not the case for all CVT patients, and this is why only 12 CVT patients had funduscopic examinations, and not all patients had a lumbar puncture documenting a CSF opening pressure. Nevertheless, because the main goal of the study was to describe radiologic findings, we thought it was more important to select a population of patients with standardised radiologic studies rather than patients with homogeneous clinical evaluations.

CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that the absence of MRI findings suggestive of raised ICP in a patient with an “IIH-like” presentation should prompt a very careful evaluation of the cerebral venous sinuses with MRV in order to definitively rule out CVT. Although increased perioptic CSF, flattening of the globe, and empty sella are more commonly found in IIH patients, they are also present in some patients with CVT. These MRI signs should not be considered “diagnostic of IIH,” but should prompt systematic investigation for all causes of raised ICP.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This study was supported in part by an unrestricted departmental grant (Department of Ophthalmology) from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, and by National Insitutes of Health/National Eye Institute (NIH/NEI) core grant P30-EY06360 (Department of Ophthalmology). Dr. Bruce receives research support from the NIH/NEI (K23-EY019341). Dr. Newman is a recipient of the Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruce B, Biousse V, Newman N. Update on idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agid R Farb RI Willinsky RA et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the validity of cross-sectional neuroimaging signs. Neuroradiology 2006;48:521–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin 2010;28:593–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silbergleit R Junck L Gebarski SS et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): MR imaging. Radiology 1989;170:207–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George AE. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: pathogenesis and the role of MR imaging. Radiology 1989;170:21–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodsky MC, Vaphiades M. Magnetic resonance imaging in pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1686–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuh WT Zhu M Taoka T et al. MR imaging of pituitary morphology in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Magn Reson Imaging 2000;12:808–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degnan AJ, Levy LM. Pseudotumor cerebri: brief review of clinical syndrome and imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:1986–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farb RI Vanek I Scott JN et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis. Neurology 2003;60:1418–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JN Cousins C Owler BK et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: 12 cases treated by venous sinus stenting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1662–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jinkins JR Athale S Xiong L et al. MR of optic papilla protrusion in patients with high intracranial pressure. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:665–668 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gass A Barker GJ Riordan-Eva P et al. MRI of the optic nerve in benign intracranial hypertension. Neuroradiology 1996;38:769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe A Kinouchi H Horikoshi T et al. Effect of intracranial pressure on the diameter of the optic nerve sheath. J Neurosurg 2008;109:255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degnan AJ, Levy LM. Narrowing of Meckel’s cave and cavernous sinus and enlargement of the optic nerve sheath in pseudotumor cerebri. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011;35:308–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shofty B Ben-Sira L Constantini S et al. Optic nerve sheath diameter on MR Imaging: establishment of norms and comparison of pediatric patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension with healthy controls. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:366–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohr AC Riedel C Fruehauf MC et al. MR imaging findings in patients with secondary intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:1021–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biousse V, Ameri A, Bousser MG. Isolated intracranial hypertension as the only sign of cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurology 1999;53:1537–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karahalios DG Rekate HL Khayata MH et al. Elevated intracranial venous pressure as a universal mechanism in pseudotumor cerebri of varying etiologies. Neurology 1996;46:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saposnik G Barinagarrementeria F Brown RD Jr et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:1158–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology 2002;59:1492–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yigit H Turan A Ergun E et al. Time-resolved MR angiography of the intracranial venous system: an alternative MR venography technique. Eur Radiol 2012;22:980–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]