Abstract

We demonstrate the method of non-inertial lift induced cell sorting (NILICS), a continuous, passive, and label-free cell sorting approach in a simple single layer microfluidic device at low Reynolds number flow conditions. In the experiments, we exploit the non-inertial lift effect to sort circulating MV3-melanoma cells from red blood cell suspensions at different hematocrits as high as 9%. We analyze the separation process and the influence of hematocrit and volume flow rates. We achieve sorting efficiencies for MV3-cells up to EMV3 = 100% at Hct = 9% and demonstrate cell viability by recultivation of the sorted cells.

INTRODUCTION

With 7.6 × 106 deaths in 2008, of which 70% occurred in low- and middle-income countries, cancer is among the leading causes for death worldwide.1 Metastases are responsible for most cancer-related deaths and arise from tumor cells that exit the primary tumor and spread via the circulatory system.2 Tumor cells within the blood stream are referred to as circulating tumor cells (CTC).3 CTCs could represent an alternative to invasive biopsies for gathering tumor tissue for cancer diagnosis and prognosis, monitoring therapy response or metastasis research.4, 5, 6 The limiting factor for the usage of CTCs is their extremely low concentration of only 1–10 CTC per milliliter blood in human cancer patients.7 Thus, there is particular interest to enrich and isolate viable CTCs for further analysis.

The most common method for isolation and counting of CTCs uses an immunomagnetic approach. To isolate cells with this technique, magnetic beads are attached to the epithelial adhesion molecule (EpCAM) on the membrane of the CTCs using the corresponding anti-body (anti-EpCAM). The CTCs are then sorted using a magnetic field and are further analyzed by skilled operators. This method is realized on the macro-scale in the commercially available device CellSearch (Veridex, USA) which is up to date the only device that is approved by the US Food and Drug Agency (FDA). It has been used to correlate the CTC count and the clinical outcome for patients with different forms of epithelial cancers.8 Although being approved by the FDA, CellSearch still has shortcomings due to its isolation principle. The immunolabeling approach is not ubiquitous for all CTC populations.9 Further on, capture efficiency and sensitivity are still low and the isolated cells are typically not vital.3, 10 One promising way to face these challenges and to improve CTC isolation and characterization is the development of label-free Lab-on-a-Chip devices. Downscaling the processes enables the use of microfluidic techniques entailing precise control of the process parameters on the length scale of the cells and the integration of several processing steps onto one single chip.11 The manifold microscale approaches are summarized in several excellent reviews.3, 7, 12, 13 Label-free techniques avoid the need of antigen reactions and instead use intrinsic cell parameters for separation. Label-free methods can be divided into two major groups:14 active separation of cell populations exploiting external fields and passive separation utilizing differences of the biomechanical and morphological properties like size, density, or deformability. The first group is dominated by dielectrophoretic separation of cells. This technique takes advantage of differences in the interactions of the cells with an external non-uniform electric field. Various realizations of dielectrophoretic devices are summarized in Ref. 15. Most recently it was demonstrated that the handling of clinical samples with continuous flow dielectrophoretic field-flow-fractionation (DEP-FFF) is possible at average collection efficiencies of 75%.16 Another upcoming active method employs acoustophoresis for sorting.17 Using standing acoustic waves, several cancer cell lines have been separated from white blood cells with recovery rates from 72.5% to 93.9%.9 These methods, however, depend on the generation of external force fields, while passive methods exploit only the interactions of objects with the channel structure and the fluid, making the generation of external force fields expendable. The most intuitive possibility to passively sort cells by size is microfiltration. The cells are pumped through diversely designed filter-structures with changing mesh sizes to gain fractionation. Being squeezed through the filter mesh, the cells are subjected to high shear stress levels. The broad scope of microfilter devices is summarized in Ref. 14. Instead of filtering, in an approach called deterministic lateral displacement arrays of posts are used to laterally deflect the cells according to their size. This approach could improve clogging issues and enables continuous sorting with very high throughput at good sorting efficiencies of about 85%.18 Nevertheless, the devices need to be tailored for certain cell sizes. While these two methods exploit the interaction of the cells with the channel structure, inertial microfluidics sort the cells by size using the interplay of the cells with the flow field. Several methods are proposed using inertial effects at finite Reynolds numbers (Re) in straight, curved, or spiral microchannels19, 20, 21 or microscale vortices.22 To ensure that cell-cell collisions do not interfere with the inertial focusing effect, the cell concentration should not exceed ∼5 × 105 cells/ml which limits the method to low hematocrits.19 The separation efficiencies vary from 10% for the relatively small HeLa cell line (average diameter: 12.4 μm) and 23% for the larger MCF-7 breast cancer line (average diameter: 20 μm) (Ref. 22) up to 98% for the MCF-7 line.19

We present a passive and label-free device that efficiently sorts circulating tumor cells from a red blood cell suspension at a hematocrit as high as 9% (∼6 × 108 cells/ml) and sorting efficiencies up to 100%. The sorting process takes advantage of size and deformability as intrinsic biomarkers and is induced by a hydrodynamic effect at very low Reynolds numbers, the so called non-inertial hydrodynamic lift.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 To characterize our non-inertial hydrodynamic lift induced cell sorting (NILICS) device, we use the MV3-melanoma cell line. The MV3- cell line is a relatively small (average diameter: (14 ± 2) μm), highly tumorigenic and metastatic human skin cancer line.30 To demonstrate that our sorting device does not affect the viability of the cells, we recultivate the collected melanoma cells and compare their morphology and growth rate to a control culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Non-inertial hydrodynamic lift

The separation process in our device is driven by the non-inertial lift effect.29 At low Re, this cell-wall interaction is the dominant hydrodynamic effect to induce cross-streamline migration of deformable objects in shear flow.20, 31, 32

Generally, in the regime of low Re, also called the symmetric Stokes regime33 the flow field is laminar and reversible in time and, as a result, no force perpendicular to the walls occurs. However, in some situations the symmetry of the Stokes regime breaks. This can be induced by the deformation of soft objects induced by fluid flow stresses or interactions between the suspended objects.33, 34, 35 The loss in symmetry enhances the objects to undergo cross-streamline migration which is generally directed away from the wall and, in Poiseuille flow, directed towards the centerline of the flow field.25, 33, 34 In blood flow the effect is known as Fåhræus-Lindqvist effect36 and drives red blood cells (RBCs) towards the centerline of the blood vessel and eventually causes a reduction of the apparent viscosity.35 The effect is also leading to margination of leukocytes and blood platelets.37, 38

In our previous work, we examined the non-inertial hydrodynamic lift for RBCs and platelets and found good agreement of our measurements with the theoretical description of Olla.39, 26 His expression for the lateral lift velocity ,

| (1) |

depends on the shear rate , the effective radius of the object , with the elliptical semi-axes of the object, , and , and the distance z between the center of mass of the object and the nearest wall for large . Smaller distances to the wall () lead to other descriptions of the lift velocity.12, 40, 41 is a dimensionless drift velocity and depends on the viscosity ratio of the inner and outer fluid and the geometry of the object described by and . For spherical particles, and no non-inertial lift occurs. For a fixed shape, decreases with increasing viscosity ratio λ.26 This prediction has been shown to be in qualitative agreement with experiments and theoretical results for deformable lipid vesicles in microgravity42, 43 and for RBCs and platelets in a Poiseuille flow.39

Preparation of sample solutions

For the blood cell suspension blood is drawn from healthy voluntary donors obeying common ethical guidelines and anticoagulated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). We wash the blood three times in isosmotic phosphate buffered saline (PBS) of pH = 7.4 and withdraw blood plasma, blood platelets and white blood cells after each centrifugation step. The red cell solution is then centrifuged to yield a concentrated RBC solution for the experiments.

To demonstrate the sorting capability of our device we use MV3-melanoma cells (in vitro cell culture obtained from S. Schneider, University Medical Center Münster) as representative cell line for aggressive CTC. The cells are maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM, Biochrom AG) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom AG) and 1% penicillin (Biochrom AG). Confluent cells are harvested with Trypsin/EDTA (Biochrom AG). To resuspend the cells for the experiments and for the sheath flow we prepare a solution of 5% w/w of dextrane (MW: 400–500 kDa, Sigma Aldrich Inc.) in PBS. The solution is degassed in an ultrasonic bath and 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 5 mg/ml EDTA are added to prevent cell adhesion to walls and agglomeration of cells. This solution has a dynamic viscosity of ηout = 7 mPas and a density of ρout = 1.03 g/cm3. Resuspended in 2 ml of this solution the final concentration of the melanoma cells is ∼ 8 × 105 cells/ml with a measured average diameter of the melanoma cells of (14 ± 2) μm. This melanoma cell suspension is mixed with the concentrated RBC solution in ratios of 1:200, 1:20, and 1:10. Assuming a hematocrit of 100% of the concentrated RBC solution these ratios correspond to hematocrits of 0.5%, 4%, and 9% with approximately 4 × 107, 3 × 108, and 6 × 108 RBC/ml respectively.

Device design and fabrication

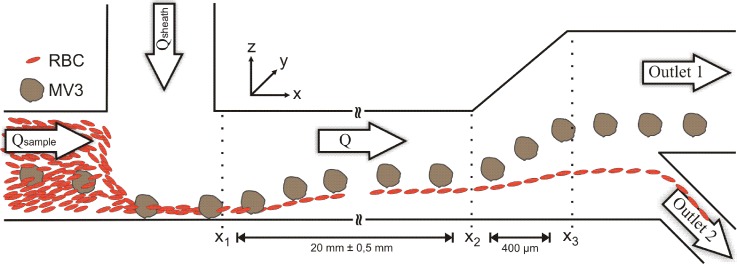

The sorting device consists of a simple single layer polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microchannel fabricated by standard soft lithography.44 Two equal sized inlets with a cross section of 66 × 63 μm converge in a rectangular main channel as shown in Fig. 1. The cells are injected into the channel with the sample flow rate Qsample and focused by the sheath flow Qsheath. The following main channel has the same cross section as the inlets and a length of 20 mm. The non-inertial lift induced separation takes place between x1 and x2 and eventually lead to different heights of the cells at position x2. We expand the microchannel in z-direction with an angle of 27° up to a height of 276 μm to further increase the absolute height difference between the two cell populations. Finally, we exploit this height difference to sort the melanoma cells into outlet 1 and the RBCs into outlet 2 as shown in Fig. 1. The disjunction of the two sorting branches is at a height of 84 μm.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing showing the sorting device and the sorting principle. The cells are introduced into the microchannel through the sample inlet with a volume flow rate Qsample = 20 μl/h and focused to the lower channel wall by sheath flows Qsheath = 180 μl/h, 380 μl/h, and 580 μl/h. While moving along the main channel the cells migrate across the streamlines between x1 and x2. This non-inertial lift leads to different heights of the cells at x2. The broadening of the channel enhances this height difference and enables cell sorting into outlet 1 and outlet 2.

Experimental setup

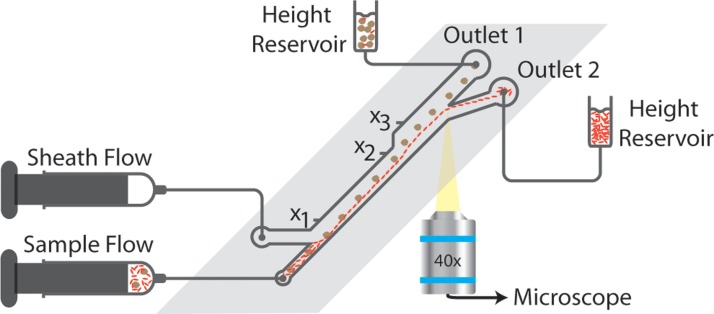

The experimental setup used for NILICS is illustrated in Fig. 2. The microfluidic device is mounted on an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200 m video microscope equipped with a Photron Fastcam 1024 PCI. Images are recorded with 40× magnification to analyze the height distribution and the sorting efficiency of the cells.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for non-inertial lift induced cell sorting. The syringes are driven by two independent syringe pumps. Videos are recorded to analyze the sorting performance of the device.

Both, the cell suspension and the dextrane solution for the sheath flow are transferred into Hamilton Gastight Syringes which are then connected to the microchannel with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubes. The total flow rate Q = Qsheath + Qsample is driven by two independent syringe pumps (PHD2000, Harvard Apparatus). The cells are injected at a constant sample flow of Qsample = 20 μl/h for all experiments. Qsheath is varied to achieve different ratios of Qsheath/Qsample = 9, 19, and 29 for Qsheath = 180 μl/h, 380 μl/h and 580 μl/h, respectively. The corresponding total flow rates are Q = 200 μl/h, 400 μl/h, and 600 μl/h with the highest Reynolds number in our experiments Re = 0.37 for Q = 600 μl/h.

The outlets are connected to two separate reservoirs using PTFE-tubes to collect the sorted cells. The heights of the reservoirs are adjusted to obtain an average RBC height of about 80 μm at the bifurcation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Separation process

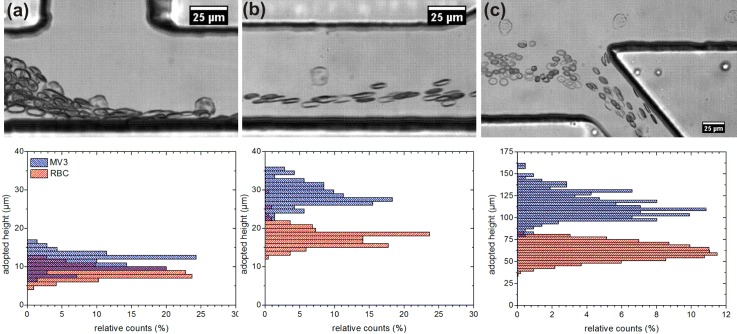

To characterize the device and to demonstrate the sorting principle images are recorded at positions x1, x2, and x3 as denoted in Fig. 1 and the adopted heights (z-position) of melanoma and red blood cells are determined. The relative counts are calculated in intervals of one micrometer at x1 and x2 and in intervals of three micrometers at x3. The data for a measurement with Qsheath = 580 μl/h is shown in Fig. 3 together with images that consist of overlays of five consecutive recorded images at each measurement position respectively.

Figure 3.

Overlays of five consecutive images with a time step dt = 8 ms at x1 (a), x2 (b), and x3 (c) with the corresponding height distributions of MV3-cells and RBCs along the channel. Note the different scale for (c) with respect to (a) and (b). MV3-cells sorted in upper outlet, RBC sorted in lower outlet (Q = 600 μl/h, Hct = 4%, ηext = 7 mPas).

At the inlet, the cells are focused to the lower wall by the sheath flow. Assuming a Gaussian distribution of the heights at x1 with its standard deviation the average height of the melanoma cells is zMV3_x1 = (11 ± 2) μm. The RBCs start a tank-treading motion when affected by the sheath flow.39, 45, 47, 48 This includes a stable inclination angle of the RBCs when passing x1 and results in an entrance height of zRBC_x1 = (8 ± 2) μm. The centers of the cell distributions are already segregated with the RBCs below the melanoma cells while the distributions itself still overlap clearly.

Flowing down the main channel the cells are migrating across the streamlines due to the non-inertial lift effect that has been examined theoretically and experimentally by other groups.23, 24, 25 The strength of the effect and therefore the drift velocity depends on size and deformability of the cells and differs for melanoma and red blood cells.26, 27 The larger melanoma cells experience a stronger lift effect than the RBCs and migrate to the center of the channel, while the RBCs stay at lower heights. This diverse migration leads to a clear separation of the cell populations until x2 and is quantified by the adopted heights of zMV3_x2 = (28 ± 3) μm and zRBC_x2 = (17 ± 2) μm as shown in Fig. 3. The following enlargement of the microchannel expands the flow field in z-direction and the streamlines diverge to fill the broader channel after the expansion.46 This leads to a scaling of the distances to the lower wall with a factor if the cells follow the streamlines and the influence of the lift force can be neglected in this part of the microchannel. The measured z-positions at x3 confirm this theoretical expectation with zMV3_x3 = (111 ± 14) μm and zRBC_x3 = (62 ± 10) μm. The enhanced magnitude of the adopted heights and the larger absolute distance between the cell populations at x3 facilitate the following sorting step.

Sorting of MV3-melanoma cells

To characterize our device and to be able to compare it to other sorting approaches, we identify sorting efficiency, sorting purity and cell enrichment as typical measures. The sorting efficiency of a single cell population is defined as

| (2) |

with the number of true sorted cells of this population ntrue and the number of false sorted cells of the same population nfalse.

The sorting purity describes the contamination of one sorted cell population by the other cell population, for example, by the remaining amount of RBC in the collected melanoma cells in outlet 1. It is defined as

| (3) |

with the true sorted cells of one population ntrue and the number ncon of contaminating cells from the other population in the collected sample.

The enrichment of the melanoma cells in outlet 1 is calculated using the ratios of melanoma to red blood cells per second21

| (4) |

To evaluate the sorting performance of the device we vary the RBC concentration and the flow conditions as described in Sec. 2B. We counted about 200 melanoma cells in average per parameter set of hematocrit and sheath flow rate and analyzed the influence of these parameters on sorting efficiency, purity, and on the enrichment of the collected melanoma cells. The experimental data is summarized in Table TABLE I..

TABLE I.

Sorting efficiency of MV3-cells under various hematocrits and flow rates. In general, it increases with the sheath flow rate and decreases with the hematocrit.

| Qsheath | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit | 180 μl/h | 380 μl/h | 580 μl/h | Average (Hct = const.) |

| Hct = 0.5% | 99.3% | 98.5% | 98.6% | (98.7 ± 0.4)% |

| Hct = 4% | 83.9% | 98.1% | 96.3% | (94.4 ± 7.7)% |

| Hct = 9% | 19.2% | 78.5% | 100.0% | (65.9 ± 41.8)% |

| Average (Qsheath = const.) | (67.5 ± 42.5)% | (91.7 ± 11.4)% | (98.3 ± 1.9)% |

At low hematocrit (Hct = 0.5%) we achieve very high sorting efficiencies for all values of Qsheath. In this regime, the sorting efficiency is independent of the flow rate within the sorting error. The average sorting efficiency for Hct = 0.5% calculated from the results of all flow rates is EMV3 = (98.7 ± 0.4)%. At a medium hematocrit of Hct = 4%, the sorting efficiency is no longer independent of Qsheath. We measure an efficiency of EHct=4% (180 μl/h) = 83.9% at the lowest sheath flow rate. For higher Qsheath the efficiency increases again to EHct=4% (380 μl/h)= 98.1% and EHct=4% (580 μl/h) = 96.3%. The average sorting efficiency for Hct = 4% is EMV3 = (94.4 ± 7.7)% which is slightly lower than the value at Hct = 0.5%. When increasing the hematocrit to Hct = 9% we observe a strongly pronounced dependence of the sorting efficiency on Qsheath. At low Qsheath the sorting efficiency drops to EHct=9% (180 μl/h) = 19.2% and even at Qsheath = 380 μl/h it is still below all values at lower hematocrits. However, at Qsheath = 580 μl/h the melanoma cells are completely sorted out of the RBC suspension. The average sorting efficiency at Hct = 9% is EMV3 = (65.9 ± 41.8)%.

The measurements show a clear trend for the sorting efficiency with sheath flow and hematocrit: increasing the sheath flow yield higher sorting efficiencies, increasing the hematocrit results in lower sorting efficiencies.

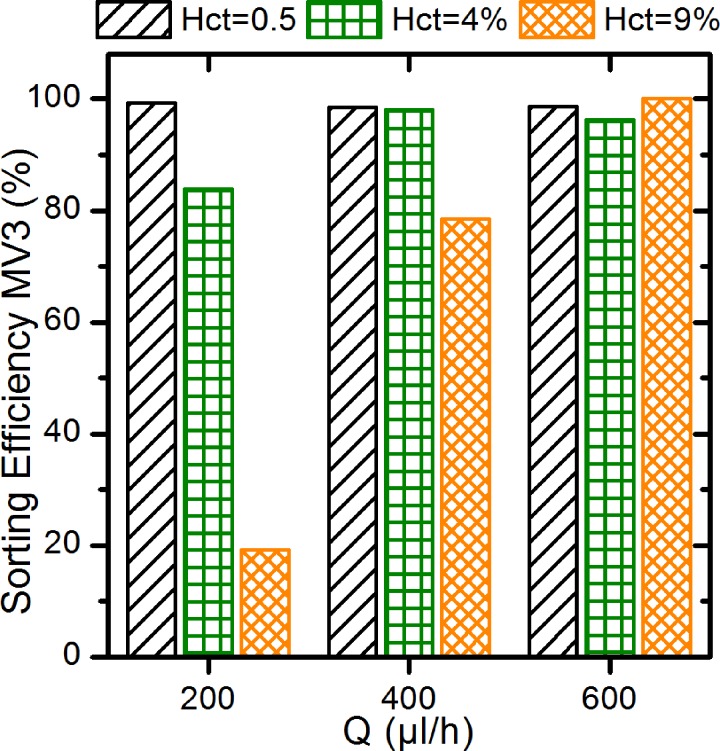

The effect of the hematocrit on the sorting efficiency is most obvious at Qsheath = 180 μl/h. At Hct = 0.5% the cells do not interact with each other and can migrate independently. With increasing hematocrit, the cell-cell-interactions become more important. At Hct = 4% a larger number of RBCs enter the channel above the melanoma cells at position x1. During the following separation process some of the melanoma cells collide with the slower migrating RBCs. These collisions disturb the migration of melanoma cells and eventually lead to lower z-positions of the MV3-cells at the end of the channel causing lower sorting efficiencies. Further increasing the hematocrit to Hct = 9% results in more collisions between MV3-cells and RBC: the sorting efficiency decreases to EHct=9% (180 μl/h) = 19.2%. This trend is mirrored by the average values of the sorting efficiency at constant flow rate and also visualized in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Sorting efficiencies of MV3-melanoma cells at all parameter sets. The trends for the sorting efficiency are clearly visible: increasing sorting efficiency with increasing flow rate and decreasing efficiency with increasing hematocrit.

The effect of the sheath flow on the sorting efficiency is most obvious at Hct = 9%: it increases with increasing sheath flow rate. The effect of the increasing sheath flow is mainly to reduce the entrance height of the RBCs. With lower entrance height less RBCs collide with melanoma cells during the following migration process. In this way fewer collisions yield a higher sorting efficiency. The effect of sheath flow rate can be extracted from the average values of the sorting efficiency at constant hematocrits, especially at higher hematocrit. The trend is also visible in Fig. 4.

For the sorting purity, we observe the same trends as for the sorting efficiency. We find a decrease of the purity with the hematocrit and an increase with the sheath flow rate.

The effect of the hematocrit on the sorting purity is based on the larger absolute number of false sorted RBCs which outnumbers the constant number of melanoma cells. Thus, even if the sorting efficiency of the RBCs is constant at all parameter sets, the higher hematocrit leads to a lower sorting purity of the MV3-cells. For Hct = 9% the sorting purity of the melanoma-cells is reduced to only 6%–9% of its initial values at Hct = 0.5%, as can be calculated with the data presented in Table TABLE II..

TABLE II.

Overview of sorting efficiency, sorting purity, and enrichment of MV3s and RBCs at all measured parameter sets.

| MV3 | RBC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hct (%) | Q (μl/h) | E (%) | P (%) | Enrich. | E (%) | P (%) |

| 0.4 | 200 | 99.3 | 20.3 | 13 | 92.1 | 99.98 |

| 400 | 98.5 | 51.6 | 49 | 98.0 | 99.97 | |

| 600 | 98.6 | 66.6 | 104 | 99.1 | 99.97 | |

| 4 | 200 | 83.9 | 10.9 | 44 | 98.1 | 99.95 |

| 400 | 98.1 | 15.1 | 50 | 98.0 | 99.99 | |

| 600 | 96.3 | 15.4 | 66 | 98.5 | 99.99 | |

| 9 | 200 | 19.2 | 1.3 | 11 | 98.3 | 99.91 |

| 400 | 78.5 | 4.6 | 43 | 98.2 | 99.98 | |

| 600 | 100 | 5.5 | 46 | 97.8 | 100.0 | |

Increasing the sheath flow at constant hematocrit improves the sorting purity due to the better focusing of the RBCs at the inlet and less collisions between MV3-cells and RBCs during the migration.

The enrichment, as defined in Eq. 3, follows the trend of the sorting purity only for changing the sheath flow rate. The higher Qsheath the higher is the enrichment, as can be seen in Table TABLE II..

The influence of the hematocrit is not as clear due to the definition of the enrichment through the ratios of MV3 to RBC in outlet 1 and in total and is only revealed at the highest sheath flow rate. In terms of enrichment, the best parameter set consists of a low hematocrit and a high sheath flow rate.

Cell viability

For probing the cell viability we prepared a sample solution with Hct = 4% and doubled the melanoma cell concentration for higher cell throughput. We sorted the cells with a sheath flow of Qsheath = 580 μl/h to test the viability at the highest shear stress used in our experiments. After three hours of sorting we centrifuged the collected sample of outlet 1 twice and resolved the cells in cell culture medium. The cells reached the growth rate of the control sample after the first week of cultivation and were kept alive for more than three weeks before we stopped the cultivation. No difference in morphology or growth rate could be observed with respect to the control sample.

CONCLUSION

We presented NILICS as a simple microfluidic method for continuous, passive, and label-free cell sorting. We demonstrated sorting of MV3-melanoma cells as an example for an aggressive circulating tumor cell type from a RBC suspension at hematocrit as high as Hct = 9% and achieve sorting efficiencies up to EMV3 = 100%. In general, with increasing hematocrit the sorting efficiency decreases. This effect can be compensated by increasing the sheath flow rate. Similarly, the sorting purity and the enrichment decrease with increasing hematocrit. However, the effect of higher hematocrit could not be compensated completely by the sheath flow for these two parameters.

Compared to other passive label-free techniques our device works at very gentle conditions. This is demonstrated by the successful recultivation of the collected cells.

NILICS has the potential for parallelization and integration in Lab-on-a-Chip systems. It can be used as a highly efficient sorting module, for example, for sample preprocessing and filtering before a following analysis on the same chip. With further optimization of geometry and sample preparation, the NILICS approach will be able to sort various cell populations at even higher hematocrit up to whole blood samples. The throughput could be increased by parallelization of several channels or by increasing the flow rates. In the latter, the inertial effect will occur and their influence on the separation has to be studied. If the device is calibrated correctly, even sorting of very low cell concentrations, as it is the case for CTCs in patient samples, will be possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the German Excellence Initiative via NIM, the German Science Foundation (DFG) and the Bavarian Research Foundation (BFS). T.F. thanks Erich Sackmann for helpful discussions. T.F. and T.G. thank Achim Wixforth for his continuous support.

References

- Ferlay J., Shin H. R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., and Parkin D. M., GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0 - Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide, International Agency for Research on Cancer, February 2012, Fact Sheet No. 297, http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed on 30/01/13).

- Steeg P. S., Nat. Med. 12(8), 895–904 (2006). 10.1038/nm1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Stott S., Toner M., Maheswaran S., and Haber D. A., J. Cell Biol. 192(3), 373–382 (2011). 10.1083/jcb.201010021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Maheswaran S., Bell D. W., Irimia D., Ulkus L., Smith M. R., Kwak E. L., Digumarthy S., Muzansky A., Ryan P., Balis U. J., Tompkins R. G., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Nature 450(20), 1235–1239 (2007). 10.1038/nature06385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerage J. B. and Hayes D. F., Br. J. Cancer 94, 8–12 (2006). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocellin S., Hoon D., Ambrosi A., Nitti D., and Rossi C. R., Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 4605–4613 (2006). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Li J., and Sun Y., Lab Chip 12, 1753–1767 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21273k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofanilli M., Budd G. T., Ellis M. J., Stopeck A., Matera J., Miller M. C., Reuben J. M., Doyle G. V., Allard W. J., Terstappen L. W. M. M., and Hayes D. F., N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 781–791 (2004). 10.1056/NEJMoa040766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustsson P., Magnusson C., Nordin M., Lilja H., and Laurell T., Anal. Chem. 84, 7954–7962 (2012). 10.1021/ac301723s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Stratton Z. S., Dao M., Ritz J., and Huang T. J., Lab Chip 13, 602–609 (2013). 10.1039/C2LC90148J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke T. A. and Wixforth A., ChemPhysChem 9, 2140–2156 (2008). 10.1002/cphc.200800349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi A., Yazdi S., and Ardekani A. M., Biomicrofluidics 7(2), 021501 (2013). 10.1063/1.4799787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Zheng W., Sun J., Zhang W., and Jiang X., Small 9, 9–21 (2013). 10.1002/smll.201200996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima I., Yee C. W., Iliescu F. S., Phyo W. M., Lim K. H., Iliescu C., and Tan M. H., Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 011810 (2013). 10.1063/1.4780062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Electrophoresis 23, 2569–2582 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S., Stemke-Hale K., Tsimberidou A. M., Noshari J., Anderson T. E., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 011807 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thévoz P., Adams J. D., Shea H., Bruus H., and Soh H. T., Anal. Chem. 82, 3094–3098 (2010). 10.1021/ac100357u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutherback K., D'Silva J., Liu L., Wu A., Austin R. H., and Sturm J. C., AIP Adv. 2(4), 042107 (2012). 10.1063/1.4758131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parichehreh V., Medepallai K., Babbarwal K., and Sethu P., Lab Chip 13, 892–900 (2013). 10.1039/c2lc40663b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Carlo D., Irmia D., Tompkins R. G., and Toner M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18892 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0704958104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Ishikawa T., Numayama-Tsuruta K., Imai Y., Ueno H., Matsuki N., and Yamaguchi T., Lab Chip 12, 4336–4343 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc40354d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur S. C., Mach A. J., and Di Carlo D., Biomicrofluidics 5(2), 022206 (2011). 10.1063/1.3576780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callens N., Minetti C., Coupier G., Mader M.-A., Dubois F., Misbah C., and Podgorski T., Europhys. Lett. 83, 24002 (2008). 10.1209/0295-5075/83/24002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abkarian M., Lartigue C., and Viallat A., Phys. Rev. Lett. 88(6), 068103 (2002). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.068103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamura A. and Gompper G., Europhys. Lett. 102, 28004 (2013). 10.1209/0295-5075/102/28004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olla P., J. Phys. II 7, 1533 (1997). 10.1051/jp2:1997201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre M., Abkarian M., Bickraj K., Stone H. A., Biorheology 43(2), 147–159 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert U., Phys. Rev. Lett. 83(4), 876–879 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H. L. and Mason S. G., J. Colloid Sci. 17, 448–476 (1962). 10.1016/0095-8522(62)90056-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Muijen G. N. P., Jansen K. F. J., Cornelissen I. M. H. A., Smeets D. F. C. M., Beck J. L. M., and Ruiter D. J., Int. J. Cancer 48, 85–91 (1991). 10.1002/ijc.2910480116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olla P., Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 453 (1999). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stan C. A., Ellerbee A. K., Guglielmini L., Stone H. A., and Whitesides G. M., Lab Chip 13, 365–376 (2013). 10.1039/c2lc41035d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farutin A. and Misbah C., Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(10), 108104 (2013). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.108104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R. and Chang H.-C., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 287, 647–656 (2005). 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R., Gordon J., Palmer A. F., Chang H.-C., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 93(2), 201–211 (2006). 10.1002/bit.20672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahraeus R. and Lindqvist T., Am. J. Physiol. 96(3), 562–568 (1931). [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H. L. and Spain S., Microvasc Res. 27(2), 204–222 (1984). 10.1016/0026-2862(84)90054-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Shaqfeh E. S. G., and Narsimhan V., Phys. Fluids 24(1), 011902 (2012). 10.1063/1.3677935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geislinger T. M., Eggart B., Braunmüller S., Schmid L., and Franke T., Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 183701 (2012). 10.1063/1.4709614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abkarian M. and Viallat A., Biophys. J. 89, 1055–1066 (2005). 10.1529/biophysj.104.056036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abkarian M. and Viallat A., Soft Matter 4, 653–657 (2008). 10.1039/b716612e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupier G., Kaoui B., Podgorski T., and Misbah C., Phys. Fluids 20, 111702 (2008). 10.1063/1.3023159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danker G., Vlahovska P. M., and Misbah C., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 148102 (2009). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.148102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y. and Whitesides G. M., Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 28, 153–184 (1998). 10.1146/annurev.matsci.28.1.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaoui B., Krüger T., and Harting J., Soft Matter 8, 9246 (2012). 10.1039/c2sm26289d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-H., Lee C.-Y., Tsai C.-H., and Fu L.-M., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 7, 499–508 (2009). 10.1007/s10404-009-0403-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantsler V. and Steinberg V., Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 258101 (2005). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.258101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T. M., Stohr-Lissen M., and Schmid-Schonbein H., Science 202(4370), 894–896 (1978). 10.1126/science.715448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]