Abstract

Background

Adrenocorticotropic hormone-producing extraadrenal paragangliomas are extremely rare. We present a case of severe hypercortisolemia due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion by a nasal paraganglioma.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old Caucasian woman was emergently admitted to our department with supraventricular tachycardia, oedema of face and extremities and hypertensive crisis. Initial laboratory evaluation revealed severe hypokalemia and hyperglycemia without ketoacidosis, although no diabetes mellitus was previously known. Computed tomography revealed a large tumor obliterating the left paranasal sinus and a left-sided adrenal mass. After cardiovascular stabilisation, a thorough hormonal assessment was performed revealing marked adrenocorticotropic hormone-dependent hypercortisolism. Due to the presence of a cardiac pacemaker magnetic resonance imaging of the hypophysis was not possible. [68Ga-DOTA]-TATE-Positron-Emission-Tomography was performed, showing somatostatin-receptor expression of the paranasal lesion but not of the adrenal lesion or the hypophysis. The paranasal tumor was resected and found to be an adrenocorticotropic hormone-producing paraganglioma of low-proliferative rate. Postoperatively the patient became normokaliaemic, normoglycemic and normotensive without further need for medication. Genetic testing showed no mutation of the succinatdehydrogenase subunit B- and D genes, thus excluding hereditary paragangliosis.

Conclusion

Detection of the adrenocorticotropic hormone source in Cushing’s syndrome can prove extremely challenging, especially when commonly used imaging modalities are unavailable or inconclusive. The present case was further complicated by the simultaneous detection of two tumorous lesions of initially unclear biochemical behaviour. In such cases, novel diagnostic tools - such as somatostatin-receptor imaging - can prove useful in localising hormonally active neuroendocrine tissue. The clinical aspects of the case are discussed and relevant literature is reviewed.

Keywords: Cushing, Paraganglioma, Nasal, ACTH, Ectopic

Background

Paragangliomas are extra-adrenal neuroendocrine tumors that arise from chromaffin cells in the sympathetic (localized in retroperitoneum and thorax) or parasympathetic (next to aortic arch, neck, and skull base) neural paraganglia [1]. Most paragangliomas are either asymptomatic or present as a painless mass and – although all contain neurosecretory granules - in only 1–3% of all cases secretion of hormones is abundant enough to be clinically significant. Although numerous reports of adrenocotricotropic hormone (ACTH)-producing adrenal phaeochromocytomas exist, ACTH-producing extraadrenal paragangliomas are extremely rare. A limited number of ACTH-expressing intraabdominal [1-5] or intrathoracic [6-11] paragangliomas can be found in literature, however, to our knowledge, only two cases of ACTH-expressing nasal paragangliomas have been reported [12,13]. Furthermore, there have been four reports of ectopic ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas, three of them localised in the sphenoidal sinus [14-16] and one intracavernously [17] as well as seven reports of ACTH-secreting olfactory neuroblastomas [18-24]. We present a rare case of severe hypercortisolemia due to ectopic ACTH secretion by a nasal paraganglioma.

Case presentation

History

A 70-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department of our hospital with palpitations, facial oedema and hypertensive crisis. The patient reported fatigue, shortness of breath, coarseness of nose and throat and progressive oedema of the face over the past year. She declined weight loss, fever, chills, diarrhoea or further gastrointestinal complaints. Her family doctor had initially suspected an allergic reaction and had treated her with a course of prednisolone (40 mg/d) over two weeks with no improvement of symptoms. Three years ago she had been diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome and had received a cardiac pacemaker. Other than arterial hypertension, treated by ramipril, no further comorbidities were reported. She did not smoke, drink alcohol or have any known allergies. Family history was unremarkable.

Clinical examination

Clinical examination revealed pitting oedema and redness of face, tachycardia and hypertension. Chest auscultation war normal, her abdomen was tender without signs of distention or peritonism. The neurological examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory and electrocardiographic findings

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed severe hypokalaemia (K+: 1,7 mmol/L), hyperglycemia without ketoacidosis and mild leucocytosis. An electrocardiogram showed supraventricular tachycardia. After haemodynamic stabilisation, a thorough hormonal assessment was performed, which revealed markedly increased serum and urinary cortisole and increased plasma ACTH. Plasma and urine katecholamines and metanephrines as well as the aldosterone/renin ratio were within normal range (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of baseline hormone values and 24-hour urinary cortisole

| Parameter | Value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| ACTH |

273 pg/ml |

[5–50] |

| Cortisole |

74.4 μg/100 ml |

[5–25] |

| DHEAS |

3.1 ng/ml |

[1.3–9.8] |

| Aldosterone |

67.1 pg/ml |

[10–160] |

| Plasma renin activity |

1.7 ng/ml/h |

[0.2–2] |

| Adrenaline |

22 ng/l |

[< 84] |

| Noradrenaline |

104 ng/l |

[< 420] |

| Dopamine |

19 ng/l |

[< 85] |

| Metanephrine |

<5 ng/l |

[< 90] |

| Normetanephrine |

19 ng/l |

[< 200] |

| 24-hour urinary cortisol | 6551.2 μg/24 h | [20–90] |

Imaging studies

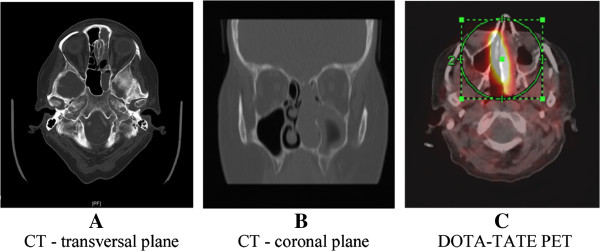

Due to initially suspected pneumonia (leucocytosis, shortness of breath), computed tomography of the chest was performed, which did not show pulmonary infiltrations. However a left adrenal mass of 1 cm diameter was detected in the lower computed-tomography (CT)-slices. Since no magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was possible due to the presence of a cardiac pacemaker, pituitary imaging was performed by computed tomography. Brain-CT revealed no pathology of the sella region, however a large tumor obliterating the left paranasal sinus was detected (Figure 1A,B). We discussed about performing a high dose dexamethasone-suppression test to differentiate between orthotopic and ectopic ACTH secretion but decided against it, given the relatively poor predictive value of the test [25] and its low diagnostic consequence in the current setting (the adreanal and paranasal masses had to be worked up irrespective of test results). Furthermore, although the dexamethasone-suppression test is not contraindicated in diabetes, we did not want to risk a new aggravation of glucose homeostasis. At this point we decided to perform somatostatine receptor imaging since the level of suspicion for ectopic ACTH production was high and initially considered an Octreoscan. However, since we were already confronted with two tumorous lesions, we sought an imaging modality with higher resolution and, taking a similar, recently published case report into account [16], decided to perform a whole-body somatostatine-receptor Positron-Emission-Tomography (PET) scan with [68Ga-DOTA]-TATE. The scan revealed markedly elevated somatostatine-receptor expression of the paranasal tumour but not of the sellar region or the left adrenal mass (Figure 1C). Based on these results, total excision of the paranasal tumor with bone reconstruction was performed.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography and [68Ga-DOTA]-TATE-Positron-Emission-Tomography of an ACTH-producing tumor localised in the left paranasal sinus. A: Computed tomography (A: coronal, B: transversal) and [68Ga-DOTA]-TATE-Positron-Emission-Tomography coregistered with computed tomography (C), displaying a tumorous lesion completely obliterating the left paranasal sinus.

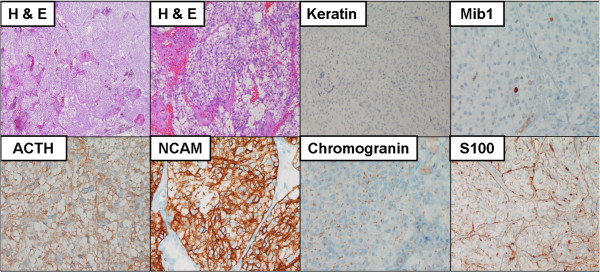

Histological findings

Initial histopathological assessment revealed an ACTH-expressing neuroendocrine tumor with the differential diagnosis including ectopic pituitary adenoma, olfactory neuroblastoma and nasal paraganglioma. The final diagnosis of paraganglioma was confirmed by two independent pathologists, based on morphological findings, immunohistochemical profile and the low-proliferative activity of the tumor (Ki67<2%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of paraffin embedded tumor tissue and immunohistochemistry with antibodies specific for keratin, S100, proliferation marker Mib1, adrenocotricotropic hormone (ACTH) and neuroendocrine markers NCAM and chromogranin.

Treatment and postoperative course

The patient was initially treated by intravenous fluids, potassium and low-dose insulin. After haemodynamic stabilisation and localising studies, the tumor was resected by a transnasal/transsphenoidal approach followed by bone reconstruction. Postoperatively there was complete remission of hypertension, hypokalaemia, hyperglycemia and oedemas. Due to the chronic suppression of the corticotropic axis, adrenal insufficiency ensued after removal of the ectopic ACTH source, rendering transient hydrocortisone substitution necessary. The adrenal mass was classified as incidentaloma, since all hormonal activity seized after removal of the paranasal tumor and no growth tendency was observed in radiologic follow up.

Genetic testing

About 75% of paragangliomas are sporadic; the remaining 25% are hereditary and have an increased likelihood of being multiple and of developing at an earlier age. After obtaining written informed consent, we performed genetic testing which revealed no mutation of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) and D (SDHD) genes thus excluding hereditary paragangliosis. Since no other features of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome were apparent, we characterised the tumor as sporadic and decided against testing for mutations of the RET-protooncogene.

Conclusions

Detection of the ACTH source in Cushing’s syndrome can prove extremely challenging, especially when commonly used imaging modalities are unavailable or inconclusive. In such settings, novel diagnostic modalities, such as somatostatin-receptor imaging, can prove useful in localising hormonally active neuroendocrine tissue. In the present case we were confronted by a very rare ACTH-producing nasal paraganglioma. The diagnostic procedure was complicated by the simultaneous discovery of two tumorous lesions and the unavailability of MRI due to the presence of a cardiac pacemaker. The ectopic ACTH-source was eventually localised by [68Ga-DOTA]-TATE-PET and was surgically removed, which led to complete remission of the hypercortisolaemic syndrome.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

ACTH: Adrenocotricotropic hormone; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PET: Positron emission tomography; SDHB: Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; SDHD: Succinate dehydrogenase subunit D; MEN: Multiple endocrine neoplasia.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TT drafted the manuscript and was involved in patient management. SZ aided in drafting the manuscript and was involved in patient management. CT, EJ and MPM supervised patient management and critically read and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

TT and SZ are junior physicians training in endocrinology. CT and EJ are senior physicians specialising in endocrinology and gastroenterology. MPM is the chief of the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology of the Hannover Medical School.

Contributor Information

Theodoros Thomas, Email: thomas.theodoros@mh-hannover.de.

Steffen Zender, Email: zender.steffen@mh-hannover.de.

Christoph Terkamp, Email: terkamp.christoph@mh-hannover.de.

Elmar Jaeckel, Email: jaeckel.elmar@mh-hannover.de.

Michael P Manns, Email: manns.michael@mh-hannover.de.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Laenger from the Department of Pathology of the Hannover Medical School for providing all immunohistochemical images. The article processing charge was funded by means of the DFG-Project “Open Access Publishing” by the German Research Council.

References

- Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE, Chun HJ, Lee HG, Lee JM. Neurogenic tumors in the abdomen: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2003;23:29–43. doi: 10.1148/rg.231025050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara M, Mori T, Seki H, Washizawa K, Amano Y, Nakahata T, Takeuchi S, Inaba H, Hotchi M, Komiyama A. Malignant paraganglioma presenting as Cushing syndrome with virilism in childhood: production of cortisol, androgens, and adrenocorticotrophic hormone by the tumor. Cancer. 1993;72:3340–3345. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3340::AID-CNCR2820721133>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka F, Miyoshi T, Murakami K, Inagaki K, Takeda M, Ujike K, Ogura T, Omori M, Doihara H, Tanaka Y, Hashimoto K, Makino H. An extra-adrenal abdominal pheochromocytoma causing ectopic ACTH syndrome. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1364–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster G, Do D, Previgliano C, Li B, LaFrance D, Heldmann M. Primary retroperitoneal paraganglioma simulating a pancreatic mass: a case report and review of the literature. HPB Surg. p. 645728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Willenberg HS, Feldkamp J, Lehmann R, Schott M, Goretzki PE, Scherbaum WA. A case of catecholamine and glucocorticoid excess syndrome due to a corticotropin-secreting paraganglioma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:52–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahir KM, Gonzalez A, Revelo MP, Ahmed SR, Roberts JR, Blevins LS Jr. Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone hypersecretion due to a primary pulmonary paraganglioma. Endocr Pract. 2004;10:424–428. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr F, Geddert H. Images in clinical medicine: ectopic Cushing's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1010540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TL, Shapiro B, Beierwaltes WH, Orringer MB, Lloyd RV, Sisson JC, Thompson NW. Cardiac paragangliomas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:827–834. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palau MA, Merino MJ, Quezado M. Corticotropin-producing pulmonary gangliocytic paraganglioma associated with Cushing's syndrome. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:623–626. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HK, Park CM, Ko KH, Rim MS, Kim YI, Hwang JH, Im SC, Kim YC, Park KO. A case of Cushing's syndrome in ACTH-secreting mediastinal paraganglioma. Korean J Intern Med. 2000;15:142–146. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2000.15.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SJR, Purushottam G, Pandurangarao K, Ravi Chander PT. Para aortic ganglioneuroma presenting as cushing's syndrome. Indian J Urol. 2007;23:471–473. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.36725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberum B, Jaspers C, Munzenmaier R. ACTH-producing paraganglioma of the paranasal sinuses. Hno. 2003;51:328–331. doi: 10.1007/s00106-002-0695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple D, Kreines K. Cushing's syndrome due to ectopic ACTH production by a nasal paraganglioma. Am J Med Sci. 1982;283:32–35. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethge H, Arlt W, Zimmermann U, Klingelhoffer G, Wittenberg G, Saeger W, Allolio B. Cushing's syndrome due to an ectopic ACTH-secreting pituitary tumour mimicking occult paraneoplastic ectopic ACTH production. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;51:809–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Otsuka F, Ogura T, Kishida M, Takeda M, Tamiya T, Nishioka T, Tanaka Y, Hashimoto K, Makino H. An aberrant ACTH-producing ectopic pituitary adenoma in the sphenoid sinus. Endocr J. 2004;51:97–103. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.51.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willhauck MJ, Popperl G, Rachinger W, Giese A, Auernhammer CJ, Spitzweg C. An unusual case of ectopic ACTH syndrome. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:63–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1297967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M, Coffin C, Courtheoux P, Theron J, Reznik Y. Case report: cushing disease caused by an ectopic intracavernous pituitary microadenoma: case report and review of the literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:424–426. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200305000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen MA, Scheithauer BW, Freeman S. Cushing's syndrome secondary to olfactory neuroblastoma. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1994;18:61–68. doi: 10.3109/01913129409016275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs L, Jones L, Marenette L, McKeever P. Cushing's syndrome: an unusual presentation of olfactory neuroblastoma. Skull Base. 2008;18:73–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno K, Morokuma Y, Tateno T, Hirono Y, Taki K, Osamura RY, Hirata Y. Olfactory neuroblastoma causing ectopic ACTH syndrome. Endocr J. 2005;52:675–681. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo BK, An JH, Jeon KH, Choi SH, Cho YM, Jang HC, Chung JH, Lee CH, Lim S. Two cases of ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome with olfactory neuroblastoma and literature review. Endocr J. 2008;55:469–475. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K07E-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzer DM, Zheng S, Nagamine M, Newman J, Benito M. Esthesioneuroblastoma (Olfactory Neuroblastoma) with Ectopic ACTH Syndrome: a multidisciplinary case presentation from the Joan Karnell cancer center of Pennsylvania Hospital. Oncologist. 2010;15:51–58. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik M, Melon J, Lambricht M, Kaschten B, Beckers A. Neuroendocrine tumor of the nasal cavity (esthesioneuroblastoma): apropos of a case with paraneoplastic Cushing's syndrome. Ann Pathol. 1987;7:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Koch CA, Patsalides A, Chang R, Altemus RM, Nieman LK, Pacak K. Ectopic Cushing's syndrome caused by an esthesioneuroblastoma. Endocr Pract. 2004;10:119–124. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron DC, Raff H, Findling JW. Effectiveness versus efficacy: the limited value in clinical practice of high dose dexamethasone suppression testing in the differential diagnosis of adrenocorticotropin-dependent Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1780–1785. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.6.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]