Abstract

When performing dose measurements on an X-ray device with multiple angles of irradiation, it is necessary to take the angular dependence of metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) dosimeters into account. The objective of this study was to investigate the angular sensitivity dependence of MOSFET dosimeters in three rotational axes measured free-in-air and in soft-tissue equivalent material using dental photon energy. Free-in-air dose measurements were performed with three MOSFET dosimeters attached to a carbon fibre holder. Soft tissue measurements were performed with three MOSFET dosimeters placed in a polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) phantom. All measurements were made in the isocenter of a dental cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scanner using 5º angular increments in the three rotational axes: axial, normal-to-axial and tangent-to-axial. The measurements were referenced to a RADCAL 1015 dosimeter. The angular sensitivity free-in-air (1 SD) was 3.7 ± 0.5 mV/mGy for axial, 3.8 ± 0.6 mV/mGy for normal-to-axial and 3.6 ± 0.6 mV/mGy for tangent-to-axial rotation. The angular sensitivity in the PMMA phantom was 3.1 ± 0.1 mV/mGy for axial, 3.3 ± 0.2 mV/mGy for normal-to-axial and 3.4 ± 0.2 mV/mGy for tangent-to-axial rotation. The angular sensitivity variations are considerably smaller in PMMA due to the smoothing effect of the scattered radiation. The largest decreases from the isotropic response were observed free-in-air at 90° (distal tip) and 270° (wire base) in the normal-to-axial and tangent-to-axial rotations, respectively. MOSFET dosimeters provide us with a versatile dosimetric method for dental radiology. However, due to the observed variation in angular sensitivity, MOSFET dosimeters should always be calibrated in the actual clinical settings for the beam geometry and angular range of the CBCT exposure.

Keywords: dosimetry, X-ray radiation exposure, MOSFET dosimeter, angular dependence

INTRODUCTION

MOSFET dosimeters have been widely used in radiation therapy [1–3] in the past. More recently, new applications for dose verification and diagnostic radiology have been reported [4–6]. MOSFETs offer a faster and simpler reading procedure compared to thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLD), and with the commercial MOSFET system, multiple detectors can be used simultaneously [7].

The rapid increase of dental cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) devices on the market has led to a greater interest in effective dose measurements, since CBCT devices produce substantially higher levels of radiation compared with the dental X-ray devices previously used. MOSFET dosimeters offer an effective method for dental dose measurements. However, when irradiated from different angles of incidence, MOSFET dosimeters demonstrate anisotropy.

Roschau et al. [8], Pomije et al. [9] and Dong et al. [10] have earlier discussed the non-isotropic response of MOSFET dosimeters. To date, all studies that have focused on the directional dependence of MOSFET dosimeters have been performed in one or a maximum of two orthogonal directions, and using 15–45º increments [8–10]. Other researchers have characterized the angular dependence using very high-energy photons or electrons that are used for radiotherapy [11–13].

The aim of this study is to investigate the angular sensitivity dependence of MOSFET dosimeters in all three rotational axes measured free-in-air and in soft-tissue equivalent material using dental CBCT photon energy. The results of this study are subsequently compared with the other studies by Roschau et al. [8], Pomije et al. [9] and Dong et al.[10].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Radiation dose measurements were performed both free-in-air and using a soft-tissue equivalent PMMA phantom. The angular dependence results of this study were then subsequently compared with the results of three other researchers. All X-rays in this study were generated using a Promax 3D CBCT X-ray device (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) with 2.5 mm Al and 0.5 mm Cu filtration. For measurements in PMMA a 100 mAs tube current was used, while a 50 mAs tube current was used in air. The tube potential was 80 kV for both measurements. The beam HVL was 7.7 mm Al with the applied kVp and filtration. The mean and standard deviation (1 SD) of the reference air kerma measured in a single exposure (one of the five repeated exposures in each angular step) with the RADCAL chamber was 3.5 ± 0.1 mGy free-in-air, and 6.9 ± 0.2 mGy in PMMA. All CBCT exposures were performed using an operating mode that hinders the rotation of the CBCT device, and thereby offers a fixed and stationary X-ray source.

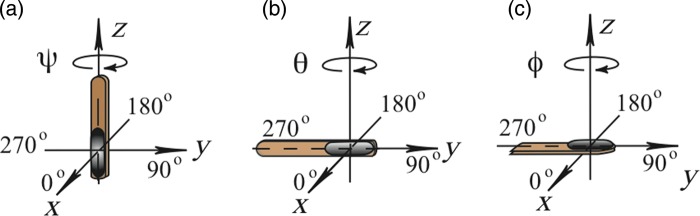

MOSFET dosimeter sensitivities were normalized to a 0º reading for the corresponding axis of rotation. The definition for 0° orientation of the dosimeter is shown in Fig. 1 for each axis of rotation.

Fig. 1.

Irradiation geometry description for angular sensitivity dependence measurements for the MOSFET dosimeter with axial (a), normal-to-axial (b), and tangent-to-axial rotation (c), co-ordinate axes and rotation angles.

The angular dependence coefficients (Cψ, Cθ, Cφ) were determined as follows:

|

where D(ψ), D(θ) and D(φ), are the average doses from five repeated exposures at rotation angles ψ, θ and ϕ, and  ,

,  and

and  are the average doses over all angle orientations for each rotation axis, respectively. Each angular position was measured with five repeated exposures to verify reproducibility and improve reliability, and to determine the standard deviation (1 SD) for each angular position. Specifically, the relative standard deviation (1 SD) was determined for each rotation axis and within each angular position, relative to the angle-specific mean as evaluated both free-in-air and in PMMA. The comparative MOSFET mean sensitivities between the studied rotational axes were verified with separate measurements in continuous full rotation exposures free-in-air and in PMMA. This was performed using three MOSFET detectors that were interchanged between repeated exposures to exclude individual detector sensitivity variations.

are the average doses over all angle orientations for each rotation axis, respectively. Each angular position was measured with five repeated exposures to verify reproducibility and improve reliability, and to determine the standard deviation (1 SD) for each angular position. Specifically, the relative standard deviation (1 SD) was determined for each rotation axis and within each angular position, relative to the angle-specific mean as evaluated both free-in-air and in PMMA. The comparative MOSFET mean sensitivities between the studied rotational axes were verified with separate measurements in continuous full rotation exposures free-in-air and in PMMA. This was performed using three MOSFET detectors that were interchanged between repeated exposures to exclude individual detector sensitivity variations.

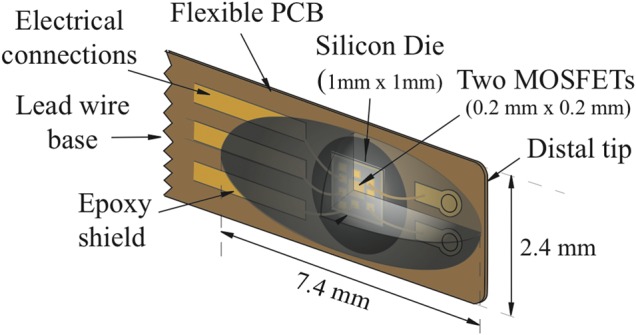

MOSFET dosimeters

The mobile MOSFET device TN-RD-70-W20 comprised a TN-RD-38 wireless Bluetooth transceiver, a TN-RD-16 reader module, high-sensitivity TN-1002RD-H detectors and TN-RD-75M software (Best Medical, Canada). Three MOSFET dosimeters were connected to the reader. TN-1002RD-H detector consists of two MOSFETs fabricated on a silicon rectangle (a die mounted on a flexible PC board and encapsulated with epoxy resin (Fig. 2). The detectors can be used either at a high- or low-bias voltage, providing high- or low-sensitivity response, respectively. In this study, all measurements were carried out using the high-bias voltage setting (13.6 V) in order to achieve the best accuracy.

Fig. 2.

MOSFET TN-1002RD-H structure. Mean thickness of the epoxy bulb was 1.02 mm.

Measurements in PMMA

Soft-tissue angular dependence measurements were performed using a fixed X-ray source and a rotating in-house constructed cylindrical acrylic phantom that was 80 mm in diameter. Dose measurements were performed in three axes using three dosimeters placed in 2.5 mm drilled holes (Fig. 3a). The smallest possible (2.5 mm) hole size was chosen to minimize the air gap and the ‘hole effect’ caused by non-attenuated direct radiation.

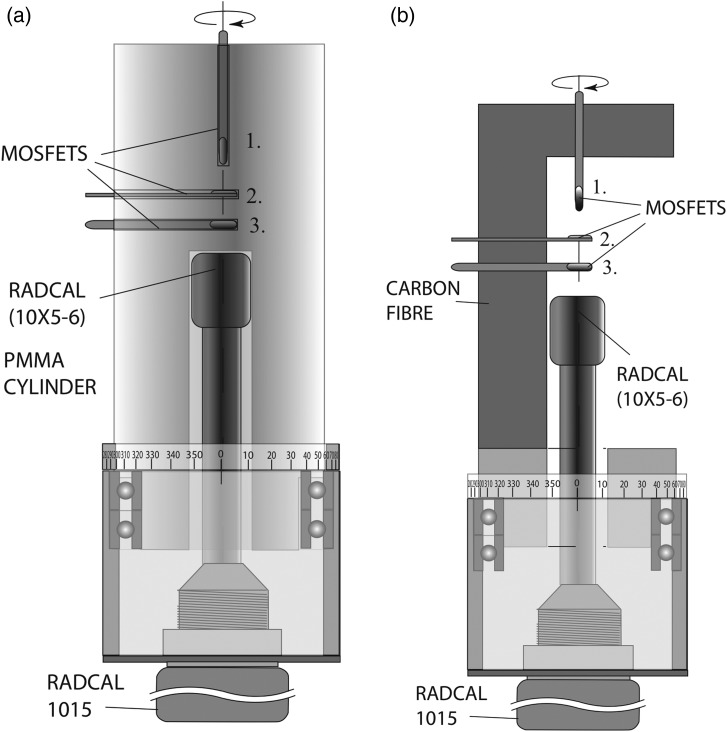

Fig. 3.

The rotation mechanism for the RADCAL dosimeter, with PMMA (a) and Carbon fibre (b) dosimeter holder, as seen from the angle of 0°.

The in-house constructed PMMA phantom was rotated 360º with 5º increments (i.e. 72 measured angles per rotation) using a mechanical support resting on ball bearings. A reference reading of every exposure was simultaneously attained using a RADCAL 1015 dosimeter and a RADCAL 10X5-6 ionization chamber (Radcal Corporation, Monrovia, CA, USA).

A separate dial ring for adjusting the rotation angle was attached to the lower part of the phantom (Fig. 3a). The alignment of the phantom was assessed with ±1° accuracy using three laser lines generated by the CBCT X-ray device.

The PMMA phantom included a hole for the ionization chamber. The ionization chamber fitted tightly into the hole to avoid any air-gap between the PMMA and the dosimeter. The ionization chamber remained stationary in the measurements while the PMMA cylinder and MOSFET dosimeters were rotated around the axis perpendicular to the anode-cathode axis to eliminate variations in irradiation caused by the heel effect (Fig. 3a).

Measurements in air

Angular dependency measurements free-in-air were performed on the same in-house constructed support used for the PMMA measurements. However, the PMMA phantom was replaced with a carbon fibre MOSFET dosimeter holder. The carbon fibre holder enabled measurements at all angles, with the exception of the angle range from 260–280°. The attenuation of the carbon fibre holder was assessed and taken into account in the angular dependence analysis, as shown in Fig. 3b.

The measurements around the x, y and z axes, both for free-in-air and PMMA, were performed by placing three dosimeters into the radiation beam so that the dosimeter axis coincided with the rotation axis, as presented in Fig. 3.

RESULTS

The mean value and standard deviation of the measured sensitivity evaluated for both free-in-air and PMMA for each rotational axis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation of the measured sensitivity free-in-air and PMMA for measured rotation axes

| Axial rot. (Ψ) | Normal-to-axial rot. (θ) | Tangent-to-axial rot. (φ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | [mV/mGy] | [mV/mGy] | [mV/mGy] |

| free-in-air | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 |

| PMMA | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

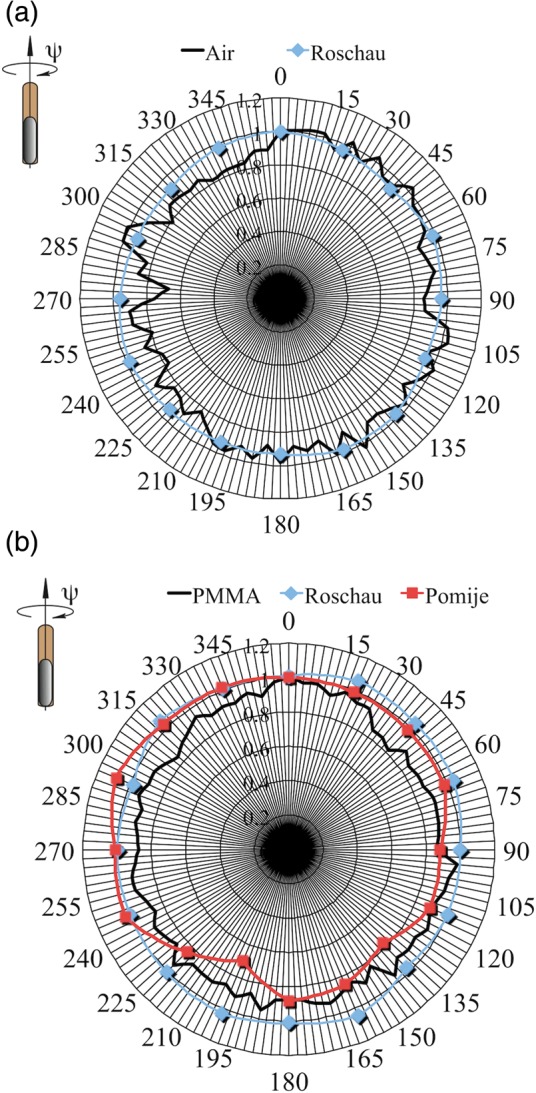

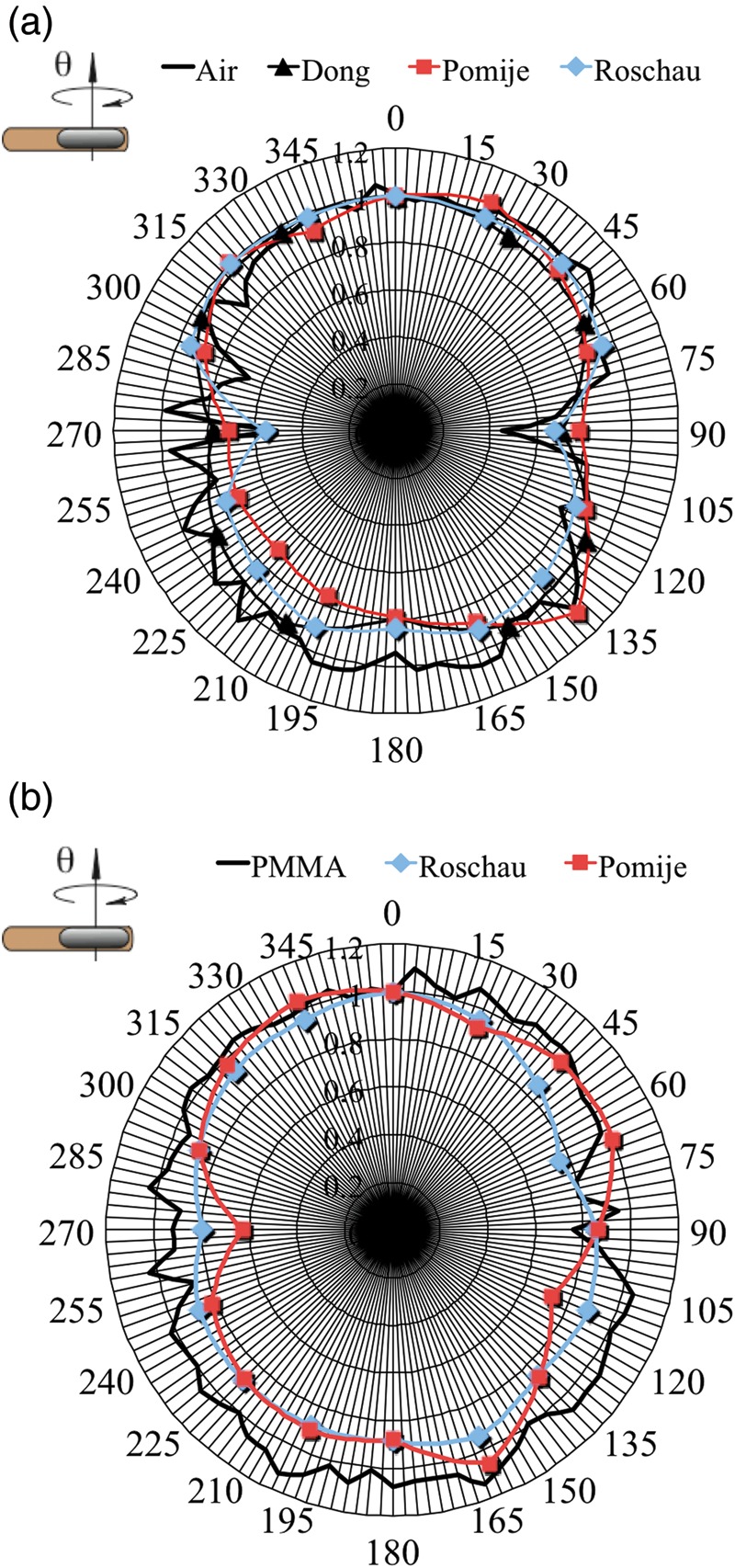

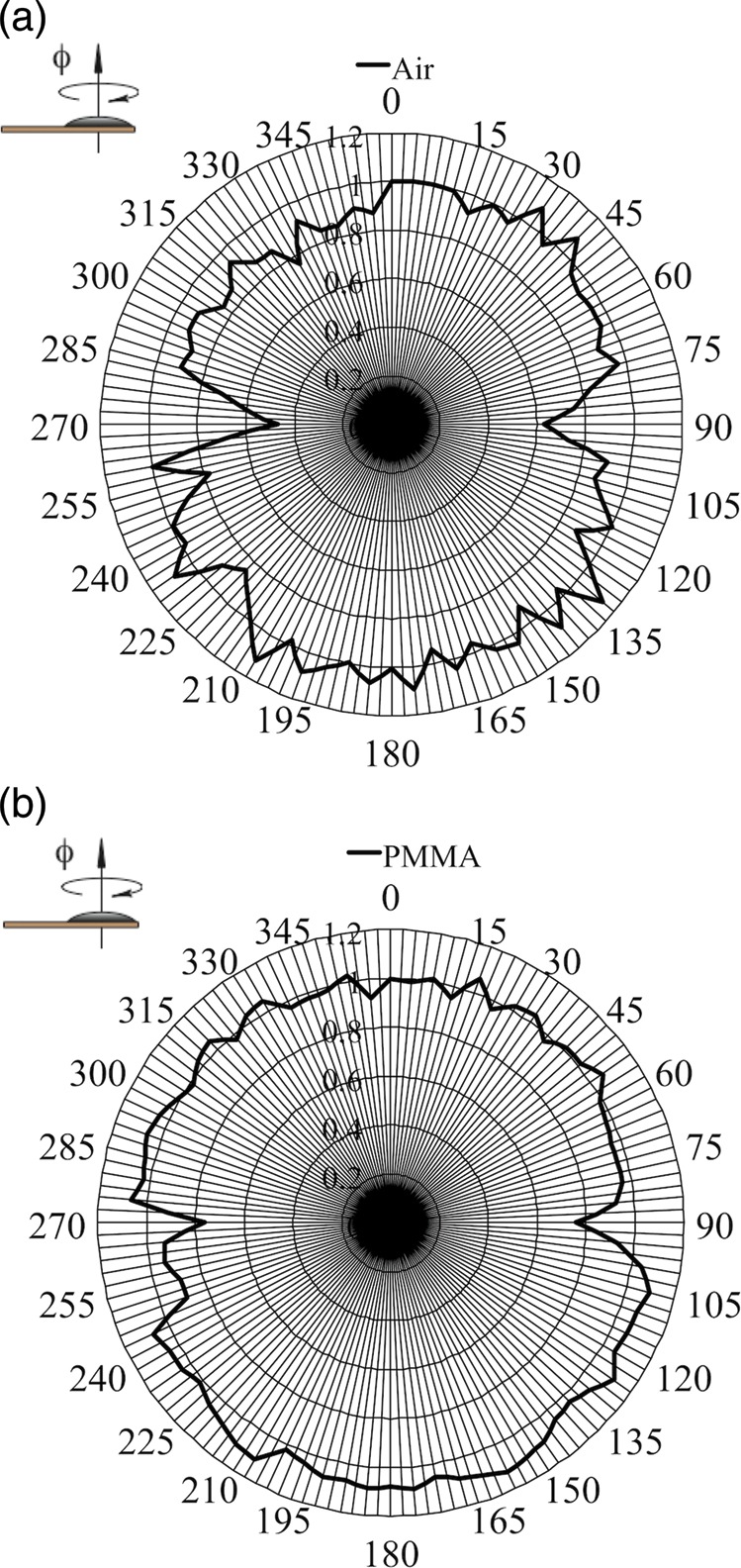

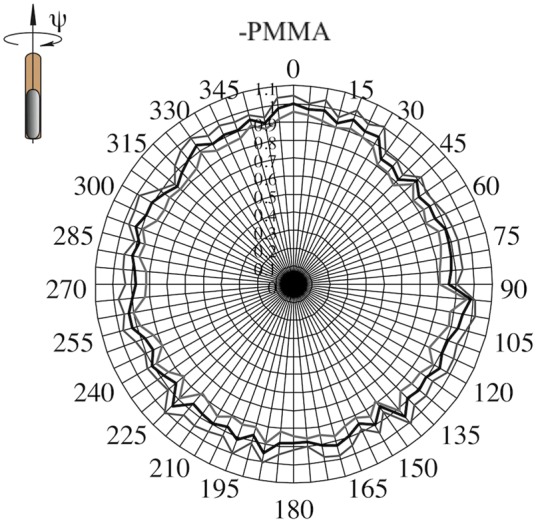

The free-in-air axial rotation measurements (each comprising five individual measurements per angular position) exhibited accuracy with a 12% standard deviation from the mean value. The response was reduced to 67% at 270° rotation (Cψ,air (270°) = 0.67) (Fig. 4a). The free-in-air normal-to-axial measurements exhibited a 16% standard deviation from the mean value. The minimum observed responses were 45% at 90° and 51% at 270°, respectively (Cθ,air (90°) = 0.45), (Cθ,air (270°) = 0.51) (Fig. 5a). The free-in-air tangent-to-axial rotation presented 18% standard deviation from the mean value. The lowest sensitivities were 63% at 90° and 47% at 270° (Cφ,air (90°) = 0.63), (Cφ,air (270°) = 0.47) (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 4.

Axial rotation dependencies (CΦ) free-in-air (a), and in PMMA (b). Zero degree orientation shown in the top left corner of each graph.

Fig. 5.

Normalized normal-to-axial rotation dependencies (Cθ) free-in-air (a), and in PMMA (b). Zero degree orientation shown in the top left corner of each graph.

Fig. 6.

Normalized tangent-to axial rotation dependencies (Cφ) free-in-air (a), and in PMMA (b). Zero degree orientation shown in the top left corner of each graph.

The PMMA axial rotation measurements demonstrated the highest accuracy with a 5% standard deviation from the mean value. The smallest response was 82% observed at 45° (Cψ,PMMA (45°) = 0.82) (Fig. 4b). The PMMA normal-to-axial measurements exhibited an 8% standard deviation from the mean value. The responses were reduced to 76% at 90° (Cθ,PMMA (90°) = 0.76) (Fig. 5b). The PMMA tangent-to-axial rotation presented 7% standard deviation from the mean value. The lowest sensitivities were 76% at 90° and 76% at 270° angles of rotation (Cφ, PMMA (90°) = 0.76), (Cφ,PMMA (270°) = 0.76) (Fig. 6b).

DISCUSSION

This study describes a novel method for the simultaneous characterization of the angular MOSFET dependency in three orthogonal directions both free-in-air and in PMMA using 5° increments. The largest variations in sensitivity were observed free-in-air for normal-to-axial and tangent-to-axial rotations, especially for the beam directed towards the MOSFET distal tip and lead wire base. Figures 4–6 seemed to indicate a periodic oscillation behaviour in each 5° step. However, performing a fast fourier transformation to the data did not reveal any significant amplitude corresponding to the 5° frequency. The visual effect is most probably due to the measurement noise, since our measurements were done with 5°-increments.

In PMMA, the sensitivity variations at different angles were considerably smaller due to the smoothing effect of the scattered radiation, as the scattered radiation approaches the dosimeter mainly from directions other than that of the primary beam. Also, in PMMA, the smallest variations were registered in the axial rotation. It is worth noticing that PMMA is not exactly soft-tissue or water equivalent material, especially in the lower photon energy range. However, it still provides a good reference material for studies in radiological beam qualities, as in this case. The mean sensitivity and relative ± relative standard deviation in PMMA is illustrated in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The mean sensitivity and ±relative standard deviation in PMMA. (±SD shown as shaded line.)

The angular dependencies observed in this study were subsequently compared with the results of other researchers who had applied similar X-ray tube potentials. Since the other researchers had used 22.5° or 30° angular increments, the values for plotting were obtained by linear interpolations. The original values of the other researchers are shown with markers in Figs 4–5.

Roschau et al. [8] measured the isotropic response of a Thomson-Nielsen TN-502RDI dosimeter in free air, and used a soft-tissue equivalent cylinder 5.2 cm in diameter. A 3-phase generator with 3.0 mm Al HVL was applied to produce 70 kVp X-rays. The study was made for axial and normal-to-axial rotations with the flat side of the dosimeter directed towards the beam for 0º orientation [8].

For free-in-air axial rotation Roschau et al. observed a nearly isotropic response with a standard deviation of 3.0% of the mean value [8]. This value is substantially lower than the 12.3% value observed in our study.

Similarly, Pomije et al. [9] studied the axial rotation sensitivity of a (TN-1002RD) dosimeter in soft-tissue equivalent material using 22.5° angle increments and 60 kVp, 90 kVp and 120 kVp tube voltages. A 0° angle was defined as having the epoxy side towards the beam source. The 90 kVp values demonstrated a 9.7% standard deviation (Fig. 4b). The measured 4.7% standard deviation of our study was in between the findings of Roschau et al. (2.7% SD) [8] and Pomije et al (9.7% SD) [9].

The free-in-air normal-to-axial rotation response was investigated by Pomije et al. (TN-1002RD) [9], Roschau et al. (TN-1002RD) [8] and Dong et al. (TN-1002RDI) [9]. The X-ray tube potential and HVL used for making the comparison were for Pomije et al. 90 kVp, HVL not known, and for Dong et al. 90 kVp, HVL 3.49 mm Al.

The standard deviations of the mean value were 12.5% (Pomije), 14.7% (Roschau) and 9.8% (Dong). In similar conditions, our study yielded a 12.3% standard deviation of the mean value. The greatest differences in the values were observed at 270°, with 29% and 44% response drops for Pomije and Roschau, respectively. For Dong et al. the greatest drop occurred at 90° (30% response drop). Similarly this study showed the largest response drop at 90° (55%).

Roschau et al. [8] and Pomije et al. [9] also studied the normal-to-axial rotation response in PMMA, yielding 7.4% and 11.6% standard deviations of the mean values, respectively (Fig. 5b). The results from our measurements were non-isotropic, with a 15.8% standard deviation of the mean. Pomije et al. observed the largest difference at the 270° angle (an almost 40% response drop from the normalized value). Similarly, Roschau et al. observed the largest response drop (20%) at the 270° angle. In our study, however, the largest deviation was observed at the 90° angle (24% response drop).

Our results indicated that the relative standard deviation of the mean in the tangent-to axial rotation was 17.6% free-in-air (Fig. 6a) and 7.1% in PMMA (Fig. 6b).

The main reason for this non-isotropic response lies in the technical design and manufacturing method of the MOSFET dosimeter. Epoxy resin is commonly used for encapsulating, and hence shields the MOSFET dosimeters. The thickness of 25 dosimeters were measured to evaluate the size and thickness variation in the epoxy, which was assumed to cause the differences in the dose readings when the dosimeter was irradiated from different angles of incidence. The average thickness of the epoxy bulb, excluding the flexprint, was 1.02 mm with 0.03 mm standard deviation. The most significant effect of the epoxy thickness on sensitivity was estimated to occur between the angles of 0° and 180°, which would represent the minimum and maximum epoxy layer thicknesses.

The variation in the dimensions was considered to be a negligible source of the sensitivity differences in the air at 0° and 180º angles. At these angles the response differences were 2% for axial rotation, 6% for normal-to-axial rotation, and 0% for tangent-to-axial rotation. Thus, the epoxy bulb shape has a much smaller effect on the sensitivity than do the distal structure and the lead-wire base.

When performing rotational exposures, as in partial arc CBCT examinations, the use of angle-specific sensitivity correction factors for MOSFET measurements should be emphasized. However, this would require correction of the MOSFET voltage signal synchronized with the angular movement of the CBCT X-ray tube, which is not applicable with current technology. Furthermore, anisotropic exposure near attenuation interfaces, e.g. bones, could nevertheless cause errors in the dose reading (i.e. if anisotropy of the exposure incidentally matches the anisotropy of the dosemeter sensitivity in a certain location). This cannot be corrected.

The method of measuring the MOSFET dosimeter angular response in 5° steps used in this study is capable of revealing local response variations, especially free-in-air at 90° and 270° degree angles. This study also included the tangent-to axial measurements free-in-air and in PMMA using dental photon energy, which to our knowledge has not been formerly studied before.

This study confirms the need to take angular dependency into account when using multiple angles of irradiation in a single examination. Fortunately, the presence of scattered radiation reduces the angular variation produced when using MOSFET dosimeters in anthropomorphic phantoms for organ dosimetry, one of the best uses for MOSFET dosimeters in clinical practice. The observed angular dependence shows that MOSFET dosimeters provide a versatile dosimetric method for dental radiology applications, such as CBCT. However, due to the observed variation in angular sensitivity, MOSFET dosimeters should always be calibrated in the actual clinical settings, taking into account the beam geometry and angular range of the CBCT exposure.

FUNDING

This study was supported by Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butson M, Mathur J, Metcalfe P. Effect of block trays on skin dose in radiotherapy. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 1996;19:248–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butson MJ, Rosenfeld A, Mathur J, et al. A new radiotherapy surface dose detector: the MOSFET. Med Phys. 1996;23:655–8. doi: 10.1118/1.597702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulinski K, Kukolowicz P. Characteristics of the Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect Transistors for application in radiotherapy. Pol J Med Phys Eng. 2004;10:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloemen-van Gurp E, Murrer L, Haanstra B, et al. In vivo dosimetry using a linear MOSFET-array dosimeter to determine the urethra dose in 125I permanent prostate implants. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loader R, Alzeanidi A. Dual Energy Imaging and the use of MOSFETs in estimating organ doses in CT. Surrey, UK: Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, University of Surrey; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halvorsen P. Dosimetric evaluation of a new design MOSFET in vivo dosimeter Med Phys. 2005;32:110–7. doi: 10.1118/1.1827771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang C, Verhey L, Xia P. Investigation of the use of MOSFET for clinical IMRT dosimetric verification. Med Phys. 2002;29:1109–15. doi: 10.1118/1.1481520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roschau J, Hinterlang D. Characterization of the angular response of an “Isotropic” MOSFET dosimeter. Health Phys. 2003;84:376–9. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pomije B, Huh C, Tressler M, et al. Comparison of angular free-in-air and tissue-equivalent phantom response measurements in p-MOSFET dosimeters. Health Phys. 2001;80:497–505. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong S, Chu T, Lan G, et al. Characterization of high-sensitivity metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistor dosimeters system and LiF:Mg,Cu,P thermoluminescence dosimeters for use in diagnostic radiology Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57:883–91. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(02)00235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung J-B, Lee J-W, Suh T-S, et al. Dosimetric characteristics of standard and micro MOSFET dosimeters as in-vivo dosimeter for clinical electron beam. J Korean Phys Soc. 2009;55:2566–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinhikar R, Sharma P, Tambe C, et al. Dosimetric evaluation of a new OneDose MOSFET for Ir-192 energy. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:1261–8. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/5/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin MN, Norrlinger B, Heaton R, et al. Image guided IMRT dosimetry using anatomy specific MOSFET configurations. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2008;9:69–81. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v9i3.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]