Abstract

Suboptimal maternal nutrition and body composition are implicated in metabolic disease risk in adult offspring. We hypothesized that modest disruption of glucose homeostasis previously observed in young adult sheep offspring from ewes of a lower body condition score (BCS) would deteriorate with age, due to changes in skeletal muscle structure and insulin signaling mechanisms. Ewes were fed to achieve a lower (LBCS, n = 10) or higher (HBCS, n = 14) BCS before and during pregnancy. Baseline plasma glucose, glucose tolerance and basal glucose uptake into isolated muscle strips were similar in male offspring at 210 ± 4 weeks. Vastus total myofiber density (HBCS, 343 ± 15; LBCS, 294 ± 14 fibers/mm2, P < .05) and fast myofiber density (HBCS, 226 ± 10; LBCS 194 ± 10 fibers/mm2, P < .05), capillary to myofiber ratio (HBCS, 1.5 ± 0.1; LBCS 1.2 ± 0.1 capillary:myofiber, P < .05) were lower in LBCS offspring. Vastus protein levels of Akt1 were lower (83% ± 7% of HBCS, P < .05), and total glucose transporter 4 was increased (157% ± 6% of HBCS, P < .001) in LBCS offspring, Despite the reduction in total myofiber density in LBCS offspring, glucose tolerance was normal in mature adult life. However, such adaptations may lead to complications in metabolic control in an overabundant postnatal nutrient environment.

Keywords: glucose uptake, myofibers, type 2 diabetes, maternal body condition, skeletal muscle

Introduction

Recent UK guidelines highlight the importance of maternal weight in influencing the health of the offspring, including the risk of adult obesity and metabolic dysfunction (eg, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance).1 Indeed the offspring of low-body-weight or low-body-mass index mothers have been shown to be at increased risk of insulin resistance in studies worldwide.2–4 It is clear that the trajectory of risk of such noncommunicable diseases commences early in life and then increases with age.5–7 We previously reported increased fasting glycemia, mild glucose intolerance, and impaired initial insulin secretion in young male adult offspring of lower body condition score (LBCS) ewes, independent of any change in birth weight.8 The aim of this study was to determine in the same animals whether this effect worsened with age and whether it was mediated by changes in skeletal muscle structure and insulin signaling mechanisms.

In this study, we focused on skeletal muscle as this is the primary tissue for glucose disposal postprandially, and changes in skeletal myofiber composition and capillary density are linked with type 2 diabetes9 and obesity.10 We have previously shown in sheep that either early or late gestation undernutrition reduced total myofiber and capillary density in the late gestation fetus (no effect on body weight) and that the effect of the late gestation maternal undernutrition was predominantly on the density of the slow-twitch myofibers.11 In sheep, a 50% global nutrient restriction in the periconceptional period (−18-6 days gestation [dGA]) similarly reduced myofiber number in the midgestation fetus (no effect on fetal weight)12 and a 50% maternal undernutrition from 28 to 70 dGA decreased total myofiber number and increased fast myosin type IIb isoform levels in 8-month-old offspring (live weight was increased).13 In the present study, we investigated the effect of a change in maternal body condition before and throughout gestation to reflect the situation in humans that women who are lean during pregnancy are generally also lean before entering pregnancy. Previously in rodents a 40% global restriction throughout gestation reduced birth weight and reduced myofiber number in the neonatal guinea pig.14 Such changes in muscle mass and composition may contribute to later insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, but to our knowledge this has not yet been determined together in 1 animal model.

Insulin resistance in muscle is one of the earliest identifiable abnormality in prediabetic patients.15 Low birth weight has been associated with reduced expression of protein kinase C zeta (PKCζ), the p85α and p110β subunits of phosphoinositol-3-kinase, and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4) in skeletal muscle of young Danish men,16 which could be a precursor to longer term altered glucose handling. Recently we found that GLUT-4 and insulin receptor messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were increased in fetal sheep skeletal muscle following late gestation maternal undernutrition and that these effects were accompanied by a decrease in slow-twitch myofiber density.11 The GLUT-4 protein levels were reduced in young adult sheep perirenal fat following late gestation maternal undernutrition, and this was associated with impaired glucose tolerance (no effect on birth weight or weight at 1 year).17 The content of GLUT-4 was lower in skeletal muscle of 8-month-old lambs following a 50% nutrient restriction from 28 to 70 dGA.13 A low-protein diet during pregnancy and lactation led to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle in 15-month-old rat offspring (no effect on weight) and was associated with reduced expression of PKCζ in soleus muscle.18

In a range of species including humans, offspring phenotype can be influenced by the developmental environment even within the normal range.19 We hypothesized that the effect of changes within the normal range maternal body condition on glucose tolerance of their offspring would worsen in mature adulthood. Therefore, in sheep we determined the effect of a higher or lower maternal body condition on mature adult offspring response to a glucose load in vivo. To investigate mechanisms contributing to glucose tolerance, we measured the uptake of glucose into isolated skeletal muscle strips, skeletal muscle morphology, and the expression of insulin signaling proteins in skeletal muscle and fat.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were carried out with local ethics approval and in accordance with the regulations of the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Animals and Study Design

The BCS is a system used to estimate the amount of muscle and fat coverage in the third lumbar region and is measured on a scale of 1 to 5 (emaciated to obese).20 The study design and animal husbandry are described in full by Cripps et al8. Briefly, second-parity welsh Mountain ewes were housed individually on straw and established at a BCS of 2 (LBCS) or greater than or equal to 3 (higher BCS [HBCS]) by adjusting the daily ration of a complete pelleted diet (Charnwood Milling Co Ltd, Suffolk, UK). Ewes were mated and maintained at the desired BCS by adjusting daily rations and gestational increases in ration were applied according to standard guidelines.21 To achieve the LBCS, animals were fed a daily energy intake of ~57% the HBCS group. The ewes were allowed to deliver spontaneously, and female offspring were removed from the study. From birth, ewes and intact male offspring were housed in 2 groups according to the maternal BCS and the ewes were fed 1.25 times (birth to 2 weeks) and 1.5 times (3-12 weeks) their term diet ration in order to maintain their BCS during the lactation period8 (at 10 weeks: LBCS ewes, 42.3 ± 1.3 kg/1.7 ± 0.0 BCS vs HBCS ewes, 55.2 ± 1.8 kg/3.1 ± 0.1 BCS. P < .001). At 12 weeks the lambs were weaned, housed as 1 group and allowed creep pelleted diet (as fed providing 10.59 MJ/kg and 18 g crude protein per 100 g. Prestige lamb pellets (Detox, BOCM Pauls Ltd, UK), hay, and water were provided ad libitum until 24 weeks. Twenty-four-week-old male offspring were fed a ration of creep pelleted diet (0.75 kg/sheep/day) with hay and water ad libitum. From 32 weeks until 1.5 years of age, male offspring were housed as 1 group and fed standard pelleted diet (0.5-1.0 kg/sheep per d. As fed providing 10.38 MJ/kg and 18 g crude protein per 100 g. Ewbol 18, BOCM Pauls Ltd., UK) with hay and water ad libitum.

An initial study was conducted at 1.5 years8 (17 LBCS and 19 HBCS intact rams). Between 1.5-and 4-year-old (life expectancy of sheep is approximately 10-12 years), animals were kept on grass (as 1 group) from May to October or indoors (November to April) with access to standard pelleted diet (0.9-1.2 kg/sheep per d, ewbol 18 following assessment of flock weight and BCS) with hay and water ad libitum. There were no differences between the groups at 2 years of age in body weight (HBCS, 82.9 ± 1.4; LBCS, 84.1 ± 2.0 kg P = .6) and BCS (HBCS, 2.5 ± 0.1; LBCS, 2.5 ± 0.1 P = 1.0), or at 3 years of age in body weight (HBCS, 85.7 ± 1.6; LBCS, 87.6 ± 1.1 kg P = .4) and BCS (HBCS, 2.8 ± 0.1; LBCS, 3.0 ± 0.1 P = .3). After 1.5 years, 5 rams died due to either infection or fighting accidents (rams were intact). At 210 ± 4 weeks in 10 LBCS and 14 HBCS intact male singleton offspring, we measured body weight, BCS by palpitation, and fat and muscle depth by ultrasound scanning.22

Glucose Tolerance Test

At 210 ± 4 weeks, the mature intact adult male offspring were acclimatized to metabolic carts for 5 days with daily pelleted ration and ad libitum access to hay. Pelleted food was given 27 hours before, and hay was removed 19 hours before, the administration of the glucose bolus. Sheep were given ad libitum access to water throughout the protocol. A temporary intravenous (iv) catheter (Radiopaque FEP 14G × 140 mm; Abbott Laboratories Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) was placed in the jugular vein via a small incision in the skin under local anesthesia (2 mL Lignol, Arnolds Veterinary Products Ltd, Shrewsbury, UK). A 2-hour recovery period was allowed prior to the iv glucose tolerance test (GTT). The blood samples (7 mL) were collected before (−30, −15, 0 minutes) and after (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, 210 minutes) an iv glucose bolus (0.5 g/kg body weight over 2 minutes) onto chilled EDTA/fluoride tubes (Teklab Ltd, Durham, UK). These were centrifuged, and the plasma were frozen in aliquots and stored at −80°C. Once the procedure was completed, animals were given a standard pelleted ration and hay was returned.

Postmortem

The last pelleted feed was given 27 hours before, and hay was removed 19 hours before, the postmortem. Water was provided ad libitum. Animals were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (iv 145 mg/kg). Body weight, crown-rump length, abdominal circumference, biparietal diameter, femur length, and shoulder height were recorded. Under sterile conditions major organs were weighed. A 1-g sample of pancreas was placed into 10 mL of 180 mmol HCl on ice and the tissue minced with scissors before being placed in a sonication bath for 30 seconds. The sample was then left overnight at 4°C, centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 minutes and the supernatant collected and frozen at −80°C.

Gastrocnemius and soleus muscle weights and mid-belly circumferences were recorded. Mid-belly muscle samples of the vastus lateralis and soleus muscles were removed immediately after death and were frozen by immersion into freezing isopentane (fibers in a vertical orientation, for histology) and liquid nitrogen (for molecular biology). All samples were stored at −80°C.

Glucose Uptake Studies

The uptake of glucose into isolated muscle strips was measured using techniques adapted from reference 18. Briefly, small strips (~50 mg) were taken from the vastus, soleus, and gastrocnemius muscles and placed in chilled Tyrode solution (137 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L glucose, 5 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L NaHCO3, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.5 mmol/L CaCl2, 10 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 2 mmol/L pyruvate, 38 mmol/L mannitol, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA], pH 7.4) until commencement of the uptake experiment. All incubations were then carried out at 38°C in a shaking water bath. The strips were placed in 5 mL of warmed Tyrode solution for 10 minutes and then incubated for a further 20 minutes in an identical medium in the presence or absence of insulin (16 nmol/L, Novo Nordisk, UK). The strips were blotted on filter paper and incubated for 10 minutes in 3 mL Tyrodes solution supplemented with 8 mmol/L [3H]methyl glucose (437 µCi/mmol) and 32 mmol/L [14C]mannitol (8 µCi/mmol; GE Healthcare, UK). After incubation, the muscle strips were blotted on filter paper to remove any residual radioactive buffer and then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Frozen muscle strips were homogenized in 400 µL of water and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 minutes. Supernatant 3H and 14C activity was determined simultaneously by liquid scintillation counting (Tricarb 2100TR, PerkinElmer, UK). Briefly, 300 μL was put into a scintillation vial along with 6 mL of Optiphase “Hisafe” II scintillation fluid (PerkinElmer, Massachusetts) and each vial run on the counter for 5 minutes. Protein levels were measured using Coomassie blue protein assay and glucose uptake corrected for the amount of protein. Extracellular space was corrected by subtracting mannitol levels.

Immunohistochemistry

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK), unless otherwise stated. Primary antibodies were mouse antiskeletal fast myosin antibody, clone MY32 (to positively indentify fast myofibers, cat no. M4276) and polyclonal rabbit antihuman von Willebrand factor (to positively identify capillary endothelial cells. DakoCytomation, cat no. A0082). In brief, 10 μm transverse cryosections from the midbelly of the skeletal muscles were fixed in water-free acetone at room temperature for 15 minutes, and endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubation in 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes. Nonspecific protein interactions were blocked with Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal calf serum and 1% BSA for 30 minutes and then incubated with either antiskeletal fast myosin antibody (1:100) or antihuman von Willebrand factor antibody (1:300) at 4°C overnight. All antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). After rinsing with TBS, the sections were incubated for 30 minutes with biotinylated antimouse (1:400) or antirabbit (1:400) antibody. Sections were washed and treated for 15 minutes with streptavidin biotin–peroxidase complex (1 + 1:200) and then for 10 minutes in amino ethyl carbazole. Finally, sections were counterstained with Mayers hematoxylin and baked with crystal mount (AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) before being mounted in Pertex (Surgipath, Peterborough, UK). A negative control section was processed simultaneously (methodology as above, replacing the primary antibody with TBS).

Capillaries were hard to identify in the frozen sections and, therefore, these were reembedded in paraffin to allow thinner sections to be cut. In brief, muscle cryosections (4 μm) were reembedded in paraffin and then deparaffinized in clearene (2 × 5 minutes) and rehydrated through graded alcohols (5 minutes in each) to 70%. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubation with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 minutes. Slides were covered with working pronase solution (DakoCytomation, Denmark) and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Sections were then washed in TBS (3 washes × 2 minutes), immersed in avidin solution for 20 minutes, rinsed in TBS, immersed in biotin solution for 20 minutes, and rinsed in TBS. Sections were incubated in DMEM containing 20% calf serum and 1% BSA culture medium for 20 minutes to block nonspecific protein interactions. Following this, anti-human von Willebrand factor antibody (1:300) was applied and the sections were incubated at 4°C overnight. After rinsing with TBS, sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit (1:400) antibody for 30 minutes. Sections were washed and treated with streptavidin biotin–peroxidase complex (1 + 1:200) for 30 minutes and then with diaminobenzidine for 5 minutes. Sections were rinsed in TBS and washed in running tap water (5 minutes). Finally, sections were counterstained with Mayers hematoxylin and dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in clearene and mounted in Pertex (Surgipath, Peterborough, UK).

Image Analysis

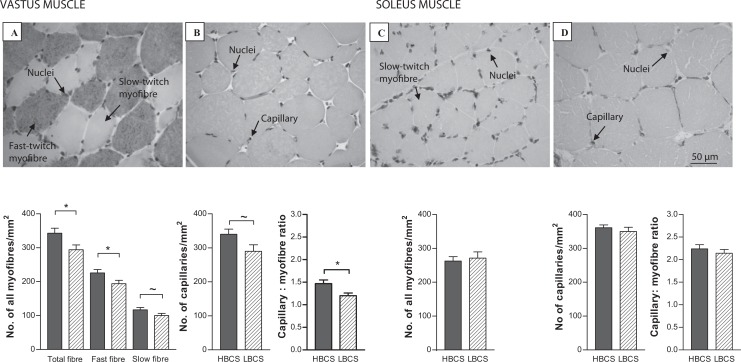

The myofiber density and size in the sections was assessed using a photomicroscope (Zeiss, Axioskop II) and the KS-400 image analyzing system (Image Associates, Bicester, UK). Five microscopic images (validated as good representation of overall myofiber density, with <2% error), with ×40 objective, were selected randomly from each section and imported into the KS-400 image analyzing program. In each of these fields of view the total fascicular area was calculated, and using a nonbiased counting frame, all myofibers, fast-twitch myofibers (identified as the red positively stained fibers) and slow myofibers (negatively stained white fibers, Figure 1A) were counted, and their density expressed as the number of fibers per mm2 fascicle. The average cross-sectional area (CSA) of the myofibers was defined by manually drawing around 41 individual fast-twitch and 24 slow-twitch fibers, with the cursor. Obvious deviations from a true cross section were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

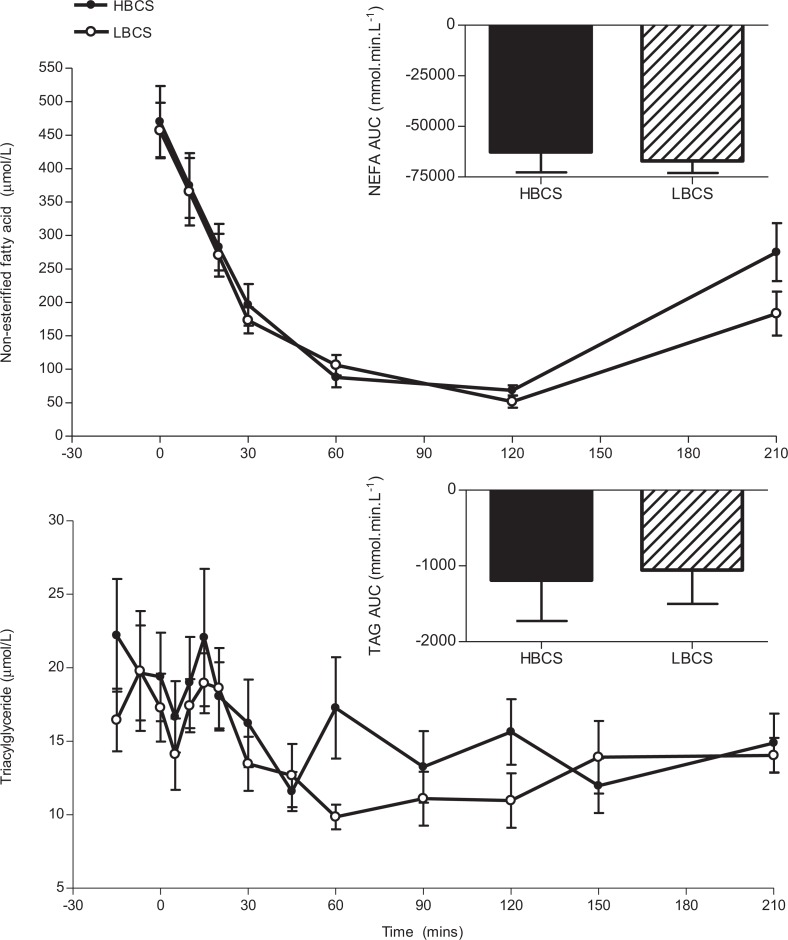

Plasma nonesterified fatty acid and triacylglyceride during the intravenous glucose tolerance test of offspring of higher body condition score (HBCS, filled bars/symbols) and lower body condition score (LBCS, hatched bars/open symbols) ewes. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from baseline plasma levels prior to the glucose bolus.

Capillaries were counted within the fascicular area of 6 random fields (validated as good representation of overall capillary density, with <2.4% error) with ×40 objective (Figure 1B) and capillary density was expressed as capillary number per mm2 fascicle. The numbers of myofibers from the same fields were counted and capillary–fiber ratio was calculated.

All measurements were made by one observer and the intraobserver variability tested by reproducing the counts from the same section, at different times. The intraobserver variability was less than 5.6% for all variables.

Western Blotting

These were performed as previously stated.8 In brief, total protein was extracted from vastus muscle and abdominal fat. The cleared protein lysates from each animal were standardized to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL in Laemmli sample buffer and equal amounts of protein for each animal (20 μg) were loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacramide gels for separation by electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in singleton and Western blotting was carried out. The primary antibodies used in this study were to insulin receptor β subunit (InsR, 1:200), PI3-kinase p85α regulatory subunit (p85, 1:1000, Upstate Biotech, New York), PKCζ (1:200), insulin-like growth factor-I receptor β-subunit (IGF-IRβ, 1:200), GLUT-4 (1:5000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and Akt1 (1:2000). All antibodies were rabbit polyclonal, except Akt1 (monoclonal mouse) and were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, California) unless stated otherwise. Autoradiographs of Western blots were imaged and the optical densities of the immunoreactive protein bands were measured. Linearity of signal was confirmed by the inclusion of 20 and 10 µg of a pooled sample on each gel. Positive controls (where available) were also included on each gel.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from liver using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK). Quality and quantity of the RNA was assessed by spectrophotometry (A260 nm/A280 nm), and the integrity of the RNA was checked by formaldehyde gel electrophoresis, staining with ethidium bromide and visualization of intact 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA bands under ultraviolet light. Total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed using standard protocols with random primers, RNase inhibitors and reverse transcriptase (Promega, UK). The 3 most stable housekeeping genes were determined using an ovine gene normalizing (geNormTM) kit developed from liver samples from our laboratory (Primer Design Ltd, UK) to be β-actin, RPL-19, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Housekeeping gene expression was measured using SYBR Green, and primers/probes were supplied in kit form (Primer Design, UK www.primerdesign.co.uk). Then real-time polymerase chain reaction (ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK) was used to evaluate mRNA levels of InsR, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), and glucose 6-phosphatase (G6Pase) using primers and probes (Eurogentec, UK) designed (Primer Express Software, Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK) with reference to published sequences (Table 1). The InsR, GR, PEPCK, and G6Pase were expressed relative to the geometric mean of the 3 housekeeping genes.

Table 1.

Primer and Probe Sequences (5′-3′) Used in the Measurement of mRNA Levels by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction.

| Target gene | Primer/probe | Sequence | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GR | Forward primer | ACTGCCCCAAGTGAAAACAGA | X70407 |

| Reverse primer | GCCCAGTTTCTCCTGCTTAATTAC | ||

| TaqMan probe | AGAAGATTTTATCGAACTCTGCACCCCTGG | ||

| G6Pase | Forward primer | TGGAGTCTTTTCAGGCATTGC | EF062861 |

| Reverse primer | CTTGAGACTGGCATTGTAGATGCT | ||

| TaqMan probe | TTGCTGAGACTTTCCGCCACATCCA | ||

| PEPCK | Forward primer | GATTGGCATCGAGCTGACAGA | EF062862 |

| Reverse primer | CGCCCATCCTCGTCATG | ||

| TaqMan probe | TCGCCCTACGTGGTGACCAGCA | ||

| InsR | Forward primer | ACCGCCAAGGGCAAGAC | AY162434 |

| Reverse primer | AGCACCGCTCCACAAACTG | ||

| TaqMan probe | AACTGCCCTGCCACTGTCATCAACG |

Biochemical Analysis

Plasma was analyzed by autoanalyzer using commercial kits as follows: glucose (hexokinase-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method [Dade-Behring]), high-density lipoprotein (Dade-Behring), low-density lipoprotein (calculated using the Friedwald formula), total cholesterol (Dade-Behring), total serum protein (Biuret reaction [Dade-Behring]), urea (urease enzyme assay [Dade-Behring]), and nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA; Alpha Laboratories Ltd, Eastleigh, UK). These analyses were measured as part of routine assays carried out at the National Health Services, Clinical Biochemistry Department, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge (Dade-Behring Dimension RXL analyzer) and at the Institute of Human Nutrition, University of Southampton, Southampton (Konelab 20 autoanalyzer).

Plasma triacylglyceride (TAG) was measured as described previously in full.23 In brief, total lipids were extracted and separated by solid phase extraction. The TAG was converted into fatty acid methyl esters and were separated and analyzed by gas chromatography (HP6890 Hewlett Packard GC system with a BPX-70 column, Agilent Technologies, Cheshire, UK).

Insulin concentrations in plasma (25 µL, collected on EDTA tubes) and extracted pancreatic tissue were measured in duplicate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; DRG Sheep Insulin ELISA; ImmunoDiagnostic Systems, Tyne and Wear, UK). The range of the assay was 0.1 to 2.5 µg/L. The interassay and intraassay coefficients of variance were 7.0% and 4.4%, respectively.

Plasma cortisol (µg/dL) was measured in duplicate using an Immulite analyzer (DPC, UK) in 10 µL of plasma (collected by EDTA tubes) by a solid-phase, competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay, with an incubation cycle of 30 minutes. The range of the assay was 0.42 to 1.70 ng/mL and the intraassay coefficient of variance was 5.7%.

Data Analysis

Nonparametric data were log transformed prior to testing and are expressed as the geometric mean (95% confidence intervals). Parametric data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Area-under-the-curve (AUC) measurements for glucose, insulin, TAGs, and NEFA were calculated (GraphPad Prism, version 3, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego) between 5 and 210 minutes (ie, following glucose administration) from baseline (preglucose bolus; ie, “incremental” AUC, Figure 1 and Table 3). For the purpose of comparison between these data and our previous study of these animals at 1.5 years,8 we also report the AUC measurements from 0 mmol/L glucose to represent the total metabolic state. Dietary groups were compared with an unpaired Student t test (SPSS version 12, SPSS Inc, Chicago). To test the effect of age (ie, data at year 1.5 vs year 4)8 and its interaction with dietary group, a repeated measures analysis of variance was used. Where a significant interaction was found between age and nutritional group a paired t test was used to compare age within dietary group. For all comparisons, statistical significance was accepted when P < .05. Trends are discussed when .05 < P < .1.

Table 3.

Plasma Hormones and Nutrients Under Baseline (Fasted) Conditions and During the Glucose Tolerance Test.a

| HBCS (n = 14) | LBCS (n = 10) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal plasma levels | |||

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4.06 ± 0.12 | 4.14 ± 0.14 | .66 |

| Insulin, pmol/L | 102 (40-144) | 91 (48-130) | .53 |

| Insulin: glucose | 28.02 ± 3.73 | 23.72 ± 3.05 | .41 |

| Cortisol, ng/mL | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.10 | .13 |

| TAG, μmol/L | 20.49 ± 2.97 (13) | 17.83 ± 2.23 | .51 |

| NEFAs, μmol/L | 470.17 ± 53.07 | 457.08 ± 41.22 | .86 |

| Total protein, g/L | 71.50 ± 0.99 | 73.60 ± 0.86 | .14 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.39 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.07 | .53 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | .61 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.01 ± 0.08 (13) | 2.11 ± 0.13 | .51 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 5.61 ± 0.37 | 5.64 ± 0.35 | .69 |

| Glucose tolerance test | |||

| Peak glucose, mmol/L | 23.41 ± 0.43 | 24.04 ± 0.39 | .31 |

| Glucose AUC, mmol.min.L− 1 | 1193.00 ± 50.70 | 1259.00 ± 64.53 | .42 |

| Peak insulin, pmol/L | 487.94 ± 49.81 | 598.72 ± 59.36 | .16 |

| Initial insulin AUC 0-5 min, nmol.min.L− 1 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.23 | .96 |

| Insulin AUC, nmol.min.L− 1 | 33.87 ± 4.50 | 43.98 ± 3.87 | .12 |

| Insulin AUC: glucose AUC | 28.38 ± 3.56 | 35.98 ± 3.79 | .16 |

a Measurements on offspring of high body condition score (HBCS) and low body condition score (LBCS) ewes. Area under the curve (AUC) calculations are from baseline. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) except for basal insulin which is shown as the geometric mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). The number within indicates where n differs from column heading.

Results

Weight and Body Composition

There was no difference between dietary groups in birth weight (HBCS, 4.02 ± 0.14; LBCS, 3.92 ± 0.23 kg), postnatal growth during suckling (0-12 weeks: HBCS, 29.6 ± 0.8; LBCS, 29.3 ± 0.7 kg), weaning to young adulthood (12 weeks-1.5 years: HBCS, 35.0 ± 1.3; LBCS, 34.0 ± 1.7 kg), and young adulthood to mature adulthood (1.5-2.5 years: HBCS, 14.2 ± 1.6; LBCS, 16.9 ± 1.7 kg). There was no difference between dietary groups in weight, BCS, or back fat depth at 4 years of age (Table 2), but back muscle depth was greater in LBCS than in HBCS offspring (P < .05). There was a significant increase between 1.5 and 4 years in body weight (1.5 years, 68.0 ± 1.1; 4 years, 81.4 ± 1.2 kg; P < .001), BCS (1.5 years, 2.1 ± 0.1; 4 years, 2.6 ± 0.1; P < .001), and back fat depth (1.5 years, 2.0 ± 0.2; 4 years, 3.3 ± 0.2 mm; P < .001) that was not different between dietary groups (data shown are the combined dietary groups). For muscle depth, there was a significant interaction between age and dietary group whereby back muscle depth increased between 1.5 and 4 years in LBCS offspring only (1.5 years, 29.4 ± 0.9; 4 years, 32.3 ± 0.7 mm; P < .05).

Table 2.

Body Biometry and Postmortem Organ Weights in 4-Year-Old Offspring.a

| HBCS (n = 14) | LBCS (n = 10) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body biometry | |||

| Age, wk | 210.2 ± 1.1 | 210.4 ± 1.0 | .90 |

| Weight, kg | 80.54 ± 1.78 | 82.50 ± 1.45 | .43 |

| BCS (1-5 units) | 2.61 (2.41-2.88) | 2.64 (2.50-2.80) | .96 |

| Fat depth, mm | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | .90 |

| Muscle depth, mm | 29.2 ± 0.9 | 32.3 ± 0.7 | .02b |

| Organ weights (as % of body weight) | |||

| Left kidney | 0.116 ± 0.003 | 0.110 ± 0.003 | .57 |

| Right kidney | 0.113 ± 0.003 | 0.112 ± 0.002 | .85 |

| Liver | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 1.08 ± 0.03 | .89 |

| Heart | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | .15 |

| Lung | 1.10 ± 0.09 (11) | 1.17 ± 0.12 (9) | .62 |

| Gastrocnemius muscle | 0.077 ± 0.004 | 0.081 ± 0.003 | .47 |

| Soleus muscle | 0.0037 ± 0.0002 | 0.0038 ± 0.0004 | .87 |

a Measurements on offspring of high body condition score (HBCS) and low body condition score (LBCS) ewes. Numbers within the parentheses indicate where group size is different from maximum. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), except for body condition score (BCS) which is shown as the geometric mean (95% confidence interval [CI]).

b P < .05.

There were no differences between the dietary groups in the weight of soleus and gastrocnemius muscles (Table 2), in gastrocnemius–femur length ratio (HBCS, 1.88 ± 0.08; LBCS, 2.04 ± 0.07) nor in gastrocnemius (HBCS, 13.13 ± 0.20; LBCS, 12.68 ± 0.24 cm) and soleus (HBCS, 2.73 ± 0.13; LBCS, 2.58 ± 0.18 cm) muscle circumference. There were no differences between the dietary groups in the major organ weights recorded (Table 2) nor in offspring body proportions (including. crown-rump length and abdominal circumference; data are not shown).

Basal Hormone and Nutrient Levels

There was no difference between the dietary groups in basal plasma hormone and nutrient levels (Table 3) nor in pancreatic insulin levels at postmortem (HBCS, 11.2 [5.4-12.9]; LBCS, 6.1 [3.3-8.2] nmol/g P = .15).

There was a small negative correlation between weight gain during suckling and basal glucose at 4 years (R2 −.197, P < .05). Basal glucose (1.5 years, 3.7 ± 0.1; 4 years, 4.0 ± 0.1 mmol/L; P < .01), insulin (1.5 years, 39.3 ± 2.5; 4 years, 106.8 ± 10.2 pmol/L; P < .001), and basal insulin–glucose ratio (1.5 years, 10.7 ± 0.7; 4 years, 26.2 ± 2.5. P < .001) increased with age, regardless of dietary group (data shown are the combined dietary groups).

Response to a Glucose Load

Intravenous GTT

There was no difference between the dietary groups in peak glucose, peak insulin, or AUC analysis (from baseline; Table 3). For AUC calculations from 0 units (as index of total metabolic state), the lack of difference between the dietary groups persisted in glucose AUC (HBCS, 2030.07 ± 67.22; LBCS, 2123.19 ± 62.41 mmol.min.L−1), initial insulin AUC 0 to 5 minutes (HBCS, 0.51 ± 0.06; LBCS, 0.64 ± 0.19 nmol.min.L−1), insulin AUC (HBCS, 52.68 ± 5.77; LBCS, 66.07 ± 6.42 nmol.min.L−1), and insulin:glucose AUC (HBCS, 25.80 ± 2.63; LBCS, 31.09 ± 2.96).

Weight gain between weaning and young adulthood was positively correlated with peak glucose (R2 .175, P < .05) and insulin (trend only; R 2 .119, P < .1). There was a decrease with age in glucose AUC (from baseline; 1.5 years, 1425 ± 48; 4 years, 1226 ± 58 mmol.min.L−1; P < .01) and initial insulin AUC 0 to 5 minutes (1.5 years, 0.51 ± 0.24; 4 years, 0.24 ± 0.08 nmol.min.L−1.0-5 min, P < .01). There was a trend for an increase with age in insulin: glucose AUC (from baseline; 1.5 years 25.6 ± 1.6, 4 years, 31.5 ± 2.7 insulin:glucose; P < .1). These age effects were not affected by dietary group.

There was no difference between dietary groups in the overall TAG or NEFA response to a glucose load (Figure 1, AUC analysis). For NEFA, but not TAG, the minimum level was reached more quickly in HBCS than in LBCS group (P < .05; see Table 4).

Table 4.

Minimum Plasma Nonesterified Fatty Acid (NEFA) and Triacylglyceride (TAG) Reached During the Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test.a

| HBCS (n = 13) | LBCS (n = 10) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum NEFA, μmol/L | 63.36 ± 8.38 | 51.74 ± 9.21 | .37 |

| Delta minimum NEFA, μmol/L (from baseline) | −406.82 ± 52.28 | −405.34 ± 36.55 | .98 |

| Time to minimum NEFA, min | 98.57 ± 7.97 | 120.00 ± 0.00 | .03b |

| Minimum TAG, μmol/L | 7.79 ± 0.85 | 6.59 ± 0.93 | .36 |

| Delta minimum TAG, μmol/L (from baseline) | −12.70 ± 2.87 | −11.24 ± 2.06 | .84 |

| Time to minimum TAG, min | 63.85 ± 9.56 | 80.50 ± 19.09 | .41 |

a Measurements on offspring of higher body condition score (HBCS) and lower body condition score (LBCS) ewes. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

b P < .05, significant difference between dietary groups.

Isolated muscle strips

As expected, basal (P < .001) and insulin-stimulated (P < .01) glucose uptake was greater in soleus than in vastus or gastrocnemius muscles. In all muscles, there was no difference in basal glucose uptake between the dietary groups (Table 5). In the soleus muscle, insulin-stimulated glucose uptake tended to be lower in the LBCS as compared to HBCS offspring (P < .1, Table 5), but there was no difference in uptake between the dietary groups in the vastus and gastrocnemius muscles.

Table 5.

Glucose Uptake into Isolated Muscle Strips.a

| HBCS (n = 10) | LBCS (n =7) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal glucose uptake, pmol/min/mg | |||

| Soleus muscle | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | .20 |

| Vastus muscle | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | .69 |

| Gastrocnemius muscle | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | .57 |

| Insulin stimulated glucose uptake, pmol/min/mg | |||

| Soleus muscle | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | ~.08 |

| Vastus muscle | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | .46 |

| Gastrocnemius muscle | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | .11 |

a Measurements on offspring of high body condition score (HBCS) and low body condition score (LBCS) ewes. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), ~ P < .1.

Reevaluation of 1.5-Year Data

Five rams were removed from the cohort in the period of time following the study at 1.5 years.8 Glucose handling data at 1.5 years were reanalyzed using only the animals that were studied at 4 years and showed that there were no differences between the groups in basal glucose (HBCS, 3.66 ± 0.06; LBCS, 3.80 ± 0.08 mmol/L P = .18) or initial insulin AUC 0 to 5 minutes (HBCS, 0.69 ± 0.08; LBCS, 0.60 ± 0.06 nmol.min.L−1; P = .41) but that glucose AUC remained significantly increased in the LBCS group (HBCS, 2183 ± 31.0; LBCS, 2283 ± 25.2 mmol.min.L−1; P < .05).

Muscle Morphology

In the vastus muscle, there was a reduction in total myofiber density, fast myofiber density (P < .05), and a trend for a reduction in slow myofiber density (P < .1) in the LBCS compared to HBCS offspring (Figure 2). Fast (HBCS, 2671 ± 110; LBCS, 2617 ± 360 µm2) and slow (HBCS, 2969 ± 202; LBCS, 3319 ± 164 µm2) myofiber CSA was similar between dietary groups. In the soleus muscle, slow myofiber density (Figure 2) and CSA (HBCS, 3793 ± 242; LBCS, 3665 ± 280 µm2) were similar between dietary groups.

Figure 2.

Myofiber and capillary density in the vastus (A and B) and soleus (C and D) muscles of offspring of high body condition score (HBCS, filled bars) and low body condition score (LBCS, hatched bars) ewes. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), *P < .05 and ~P < .1.

In the vastus muscle, capillary density tended to be reduced in the LBCS compared to HBCS offspring (Figure 2, P < .1). The capillary to myofiber ratio was significantly reduced in LBCS compared to HBCS offspring (Figure 2, P < .05). In the soleus muscle, capillary density and capillary to myofiber ratio were similar between dietary groups (Figure 2).

Gene Expression

Muscle and fat

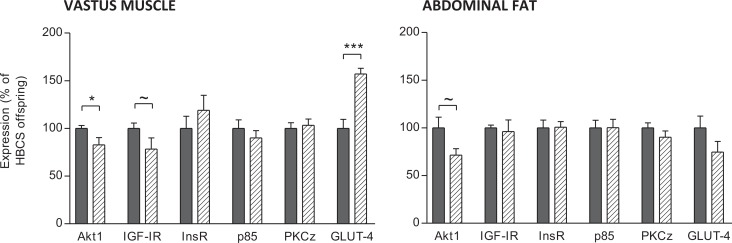

Protein levels of Akt1 were lower (P < .05) and IGF-IR levels tended to be lower (P < .1) in the vastus muscle of LBCS offspring (Figure 3). The GLUT-4 protein levels were increased in the vastus muscle of LBCS offspring (P < .001). There were no differences in InsR, PI3-kinase p85 subunit, and PKCξ protein in the vastus muscle between dietary groups. Protein levels of Akt1 tended to be reduced in the abdominal fat of LBCS offspring (P < .1, Figure 3). There were no differences in GLUT-4, InsR, IGF-IR, PI3-kinase p85 subunit, and PKCξ protein in the abdominal fat between dietary groups.

Figure 3.

Insulin signaling pathway protein expression in the vastus muscle and abdominal fat of offspring of high body condition score (HBCS, filled bars) and low body condition score (LBCS, hatched bars) ewes. Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). ~P < .1, *P < .05, and ***P < .001.

Liver

The InsR mRNA levels were increased in liver of LBCS offspring (HBCS, 0.51 (0.37-0.65); LBCS, 0.72 (0.55-0.89) arbitrary units normalized to housekeeping gene, P < .05). There was no significant difference between dietary groups in liver GR, PEPCK, or G6Pase mRNA levels (data not shown).

Discussion

Epidemiological and animal studies implicate the fetal nutrient environment as a determinant of metabolic disease in later life. Maternal body composition is linked to maternal diet and food intake and is important since the mother provides nutrition for the fetus from both her dietary intake and her own body reserves. The offspring of mothers low body mass index have been shown to be at increased risk of insulin resistance.2–4 Our previous observations showed that lowering the BCS of the ewe during pregnancy reduced glucose tolerance of young adult offspring.8 In this study, we had the rare opportunity to study the same animals again in mature adulthood and found that rather than worsening, the LBCS animals displayed no signs of altered glucose metabolism, despite reduced myofiber, fast-fiber density, and capillary to myofiber ratio in the vastus lateralis muscle. Our findings suggest that this may be due in part to adaptations in the muscle insulin-signaling pathway.

An important and novel finding of this study is that the altered glucose handling at 1.5 years in offspring of LBCS mothers8 did not persist into mature adult life, and indeed no other sheep study of glucose metabolism has followed up animals postnatally for so long following in utero undernutrition. The difference between dietary groups at 1.5 years in the response to a glucose load was still apparent when the data set was restricted only to the animals that were also studied at 4 years. Fatty acid metabolism (indicated by plasma NEFA and TAG levels) was similar between offspring groups, although the slightly longer time to minimum levels of NEFA during the GTT in LBCS animals may be a weak marker of altered insulin sensitivity in other organs such as adipose and liver. There was no difference between dietary group in insulin signaling pathway in adipose tissue, but we observed that hepatic InsR expression at the mRNA level was increased in LBCS animals. This was not associated with any change in fasting blood glucose and there was no effect on mRNA levels of genes involved with gluconeogenesis in the liver (ie, GR, PEPCK, and G6Pase). Increased liver insulin sensitivity could impact on the LCBS offspring response to dietary excess or deficiency through fatty acid synthesis, gluconeogenic, or glycogen storage pathways; however, this speculation was not tested in the current study design. In sheep offspring, exposure to a late gestation 50% undernutrition challenge increased insulin and glucose AUC at 1 year of age17 and exposure to a 50% reduction from 28 to 78 dGA increased glucose AUC in 63- and 250-day-old offspring.24 Glucose tolerance was reduced among men and women exposed to famine during late gestation, and this was more pronounced in those exposed to famine, who then became obese as adults.25 In rats, glucose tolerance of offspring of mothers fed a low-protein diet was improved at 6 to 9 weeks26,27 unaltered at 44 weeks27 and significantly worse by 17 months and exacerbated by an overabundant postnatal diet.28,29 Sheep are ruminants but have advantages as a model in that singleton offspring can be studied and also they develop key organ systems fully prenatally. In the present study, back fat and muscle and BCS increased modestly with age but at the 4 year study the animals still were of average BCS. It remains possible that if they had become obese differences between the lower and higher condition score groups in glucose handling may have persisted or worsened with age. Thus, overall these findings provide additional insight into our understanding of the influence of nutrition in early life on the risk of disorders of metabolism in adult life such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.19

Our data show that basal glucose, basal insulin, and basal insulin to glucose ratio increased with age which is consistent with signs of altered glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance. The initial insulin response to glucose (insulin 0-5 minutes AUC, a measure of the first phase insulin response) decreased from 1.5 to 4 years and this is consistent with several human studies that have reported a significant age-dependent decrease in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.30–32 However, glucose AUC (from baseline) was lower at 4 years of age than at 1.5 years (independent of dietary group) suggesting that glucose tolerance had in fact improved with age. In humans, glucose tolerance is generally thought to decrease with age,33 not as a consequence of age per se but possibly due to lower activity and weight gain. In the current study, activity levels were not assessed but it is of note that weight gain was modest (~10 kg) and the increase in BCS and adiposity was small.

The offspring of LBCS ewes had reduced total myofiber and fast-twitch density, and a tendency for reduced slow-twitch myofiber density, in the vastus muscle that does not appear to be due to changes in CSA and, therefore, could involve changes to the extracellular space, although this was not assessed. This is consistent with our previous findings that early and late gestation undernutrition periods reduced fiber density in the late gestation fetus.11 A reduction in fast fiber number has been seen in the vastus lateralis muscle of 14-day-old lambs following a 50% nutrient reduction at 30 to 70 dGA.34 A reduction in fast fibers is more likely to have a greater effect on muscle strength than a reduction in slow fibers, due to their faster speed of contraction and reduced resistance to fatigue. Studies suggest that individuals of lower birth weight have reduced muscle strength35 and a lower myofiber score36 in adult life, with a consequent increase in disability and frailty with age. Decreased strength with aging has been associated with a reduction in type II fibers.37

Our observation of a decrease in capillary to myofiber ratio and a trend for reduced overall capillary density in the vastus muscle, but not in the soleus, suggests that blood flow and muscle growth were related. Indeed, the reduction in capillary to myofiber ratio in the vastus muscle indicates that each fiber was being supplied by fewer blood vessels. In mice, impaired insulin signaling in endothelial cells led to attenuated insulin-induced capillary recruitment and insulin delivery, and reduced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.38 Our observation of decreased Akt1 (significant) and IGF-IR (trend only) levels in LBCS offspring vastus muscle are consistent with decreased muscle growth. There was a trend for only Akt1 to be lower in LBCS offspring abdominal fat. Myofiber hypertrophy and hypertrophy-associated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression is inhibited by a dominant-negative mutant of Akt1 and conversely, transduction of a constitutively active form of Akt1 increase myofiber size and VEGF production.39 Hypertrophy of myotubes, in response to IGF-I or insulin (both ligands of IGF-IR), increases secretion of VEGF.39 The VEGF is implicated in capillary remodeling/angiogenesis.40 Interestingly, Akt1 has also been implicated in angiogenesis.41 Thus, Akt1 is a mechanism through which blood vessel recruitment and muscle growth may be coupled, although in the present study reduced myofiber and capillary density in LBCS offspring vastus muscle was not accompanied by a change in myofiber CSA.

Our observed changes in skeletal muscle morphology, in particular the reduced total myofiber density in hindlimb muscle, in LBCS offspring were not associated with reduced glucose tolerance at 4 years (only a small nonsignificant decrease in insulin-sensitive glucose uptake in the soleus muscle strips of LBCS offspring was observed). The small increase in back muscle depth in the LBCS group may have contributed positively to glucose tolerance in these animals, similar to that associated with hypertrophy of muscle following resistance training.42,43 In theory, such improvement in glucose tolerance could partially attenuate any reduction in whole body glucose tolerance that might have resulted from reduced myofiber density in limb muscle.

In the vastus muscle, there were no differences in InsR, PI3-kinase p85 subunit, and PKCζ protein between dietary groups but GLUT-4 (the major insulin-responsive glucose transporter in skeletal muscle and the last stage in the insulin pathway signaling to glucose uptake) was increased in LBCS offspring. In contrast, there was no effect on these key genes in abdominal fat. In contrast, previous studies observed reduced skeletal muscle GLUT-4 in much younger (8 months) lambs following early gestation maternal undernutrition.13 So we speculate that the effects of altered skeletal muscle composition that were apparent at 1.5 years in terms of glucose tolerance8 may be offset at least in part by compensatory increases in GLUT-4 resulting in normal glucose tolerance by 4 years. While not assessed directly in the present study, changes to the GLUT-4 system might involve altered GLUT-4 translocation (from intracellular vesicular storage to the plasma membrane). Indeed, GLUT-4 protein content was unchanged but translocation was increased in the muscle of 10-day-old pups from protein restricted dams, and this was associated with normal glucose tolerance.44

Thus, we have shown that the mild glucose intolerance in young adulthood caused by gestational lower maternal diet and body composition8 was no longer detectable by mature adulthood in terms of total body glucose handling. Our observation of decreased myofiber and capillary density is likely to have originated in utero and at the young adult stage may have contributed to altered glucose handling—but by mature adulthood we speculate that the observed upregulation of GLUT-4 and increase in back muscle depth may form part of a compensatory mechanism to regulate glucose homeostasis. However, these adaptations may have limitations in an overabundant postnatal environment, where there would be increased propensity for weight gain and obesity. These findings have implications for dietary choices of mothers, even prepregnancy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Biological Services Unit (Royal Veterinary College) and to the Biological Research Facility (University of Southampton) for the care of all animals. We thank Dr Graham Burdge, Annette West, and Dr Kirsten Poore (University of Southampton) for their assistance in the TAG assay, Dr John Jackson and Mr Christiaan Gelauf (University of Southampton) for NEFA analysis, and the Histochemistry Research Unit (University of Southampton) and Dr Anthea Rowlerson (King’s College London) for advice on immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The work was carried out at Institute of Developmental Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK; Metabolic Research Laboratories, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge, UK; and at The Royal Veterinary College, Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK. LRG, PMC, SEO, and MAH contributed to the conception and design of experiments; LRG, PMC, SEO, MAH, LJH, RLC, NB, and HPP, and contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; LRG, PMC, SEO, MAH, LJH, AAS, and CC contributed to drafting and revision of this article. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: grants from The National Institute of Health (AG20608) and The Gerald Kerkut Trust. MAH is supported by the British Heart Foundation and SEO is a British Heart Foundation Senior Fellow.

References

- 1. NICE public health guidance. Dietary interventions and physical activity interventions for weight management before, during and after pregnancy. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, ed. PH27 2010; London. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fall C, Stein C, Kumaran K, et al. Size at birth, maternal weight, and type 2 diabetes in South India. Diabet Med. 1998;15(3):220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shiell AW, Campbell DM, Hall MH, Barker DJP. Diet in late pregnancy and glucose-insulin metabolism of the offspring 40 years later. BJOG. 2000;107(7):890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mi J, Law C, Zhang K, Osmond C, Stein C, Barker D. Effects of infant birthweight and maternal body mass index in pregnancy on components of the insulin resistance syndrome in China. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(4):253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, et al. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ. 1991;303(6809):1019–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Hales CN, Hirst S, Osmond C. Thinness at birth and insulin resistance in adult life. Diabetologia. 1994;37(2):150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of metabolic disease: life course and intergenerational perspectives. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(4):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cripps R, Green L, Thompson J, et al. The effect of maternal body condition score before and during pregnancy on the glucose tolerance of adult sheep offspring. Reprod Sci. 2008;15(5):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marin P, Andersson B, Krotkiewski M, Bjorntorp P. Muscle fiber composition and capillary density in women and men with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(5):382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanner C, Barakat H, Dohm G, et al. Muscle fiber type is associated with obesity and weight loss. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282(6):E1191–E1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Costello PM, Rowlerson A, Astaman NA, et al. Peri-implantation and late gestation maternal undernutrition differentially affect fetal sheep skeletal muscle development. J Physiol. 2008;586(9):2371–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Quigley SP, Kleemann DO, Kakar MA, et al. Myogenesis in sheep is altered by maternal feed intake during the peri-conception period. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005;87(3-4):241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Means WJ, Hess BW, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Maternal nutrient restriction affects properties of skeletal muscle in offspring. J Physiol (Lond). 2006;575(Pt 1):241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dwyer C, Madgwick A, Ward S, Stickland N. Effect of maternal undernutrition in early gestation on the development of fetal myofibres in the guinea-pig. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1995;7(5):1285–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(2):171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ozanne S, Jensen C, Tingey K, Storgaard H, Madsbad S, Vaag A. Low birthweight is associated with specific changes in muscle insulin-signalling protein expression. Diabetologia. 2005;48(3):547–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gardner DS, Tingey K, Van Bon BWM, et al. Programming of glucose-insulin metabolism in adult sheep after maternal undernutrition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289(4):R947–R954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ozanne SE, Olsen GS, Hansen LL, et al. Early growth restriction leads to down regulation of protein kinase C zeta and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol. 2003;177(2):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gluckman P, Hanson M, Spencer H, Bateson P. Environmental influences during development and their later consequences for health and disease: implications for the interpretation of empirical studies. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272(1564):671–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Russel A, Doney J, Gunn R. Subjective assessment of body fat in live sheep. J Agric Research. 1969;72(3):451–454. [Google Scholar]

- 21. AFRC. Energy and protein requirements of ruminants. An Advisory Manual Prepared by the AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poore KR, Cleal JK, Newman JP, et al. Nutritional challenges during development induce sex-specific changes in glucose homeostasis in the adult sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(1):E32–E39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burdge GC, Wright P, Jones AE, Wootton SA. A method for separation of phosphatidylcholine, triacylglycerol, non-esterified fatty acids and cholesterol esters from plasma by solid-phase extraction. Br J Nutr. 2000;84(5):781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ford SP, Hess BW, Schwope MM, et al. Maternal undernutrition during early to mid-gestation in the ewe results in altered growth, adiposity, and glucose tolerance in male offspring. J Anim Sci. 2007;85(5):1285–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ravelli ACJ, van der Meulen JHP, Michels RPJ, et al. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. The Lancet. 1998;351(9097):173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shepherd P, Crowther N, Desai M, Hales C, Ozanne S. Altered adipocyte properties in the offspring of protein malnourished rats. Br J Nutr. 1997;78(1):121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langley SC, Browne RF, Jackson AA. Altered glucose tolerance in rats exposed to maternal low protein diets in utero. Comp Biochem Physiol Physiol. 1994;109(2):223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petry C, Dorling M, Pawlak D, Ozanne S, Hales C. Diabetes in old male offspring of rat dams fed a reduced protein diet. Int J Exp Diabetes Res. 2001;2(2):139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson MR, Hughes SJ. The effect of maternal protein deficiency during pregnancy and lactation on glucose tolerance and pancreatic islet function in adult rat offspring. J Endocrinol. 1997;154(1):177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen M, Bergman RN, Pacini G, Porte D., Jr Pathogenesis of age-related glucose intolerance in man: insulin resistance and decreased beta-cell function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muller DC, Elahi D, Tobin JD, Andres R. Insulin response during the oral glucose tolerance test: the role of age, sex, body fat and the pattern of fat distribution. Aging (Milano). 1996;8(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gumbiner B, Polonsky KS, Beltz WF, Wallace P, Brechtel G, Fink RI. Effects of aging on insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1989;38(12):1549–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jackson R. Mechanisms of age-related glucose intolerance. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fahey AJ, Brameld JM, Parr T, Buttery PJ. The effect of maternal undernutrition before muscle differentiation on the muscle fiber development of the newborn lamb. J Anim Sci. 2005;83(11):2564–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sayer AA, Syddall H, Martin H, Patel H, Baylis D, Cooper C. The developmental origins of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(7):427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patel HP, Jameson KA, Syddall HE, et al. Developmental influences, muscle morphology, and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(1):82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hortobagyi T, Zheng D, Weidner M, Lambert NJ, Westbrook S, Houmard JA. The influence of aging on muscle strength and muscle fiber characteristics with special reference to eccentric strength. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(6):B399–B406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kubota T, Kubota N, Kumagai H, et al. Impaired insulin signaling in endothelial cells reduces insulin-induced glucose uptake by skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2011;13(3):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takahashi A, Kureishi Y, Yang J, et al. Myogenic Akt signaling regulates blood vessel recruitment during myofiber growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(13):4803–4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hudlicka O, Brown MD. Adaptation of skeletal muscle microvasculature to increased or decreased blood flow: role of shear stress, nitric oxide and vascular endothelial growth factor. J Vasc Res. 2009;46(5):504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Somanath P, Razorenova O, Chen J, Byzova T. Akt1 in endothelial cell and angiogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(5):512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smutok M, Reece C, Kokkinos P, et al. Aerobic versus strength training for risk factor intervention in middle-aged men at high risk for coronary heart disease. Metabolism. 1993;42(2):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Szczypaczewska M, Nazar K, Kaciuba-Uscilko H. Glucose tolerance and insulin response to glucose load in body builders. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(1):34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gavete ML, Martin MA, Alvarez C, Escriva F. Maternal food restriction enhances insulin-induced GLUT-4 translocation and insulin signaling pathway in skeletal muscle from suckling rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146(8):3368–3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]