Abstract

Werner syndrome (WS) is genetically linked to mutations in WRN that encodes a DNA helicase-nuclease believed to operate at stalled replication forks. Using a newly identified small molecule inhibitor of WRN helicase (NSC 617145), we investigated the role of WRN in the interstrand cross-link (ICL) response in cells derived from patients with Fanconi Anemia (FA), a hereditary disorder characterized by bone marrow failure and cancer. In FA-D2−/− cells, NSC 617145 acted synergistically with very low concentrations of Mitomycin C (MMC) to inhibit proliferation in a WRN-dependent manner, and induce double strand breaks (DSBs) and chromosomal abnormalities. Under these conditions, ATM activation and accumulation of DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci suggested an increased number of DSBs processed by nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ). Rad51 foci were also elevated in FA-D2−/− cells exposed to NSC 617145 and MMC, suggesting that WRN helicase inhibition interferes with later steps of homologous recombination (HR) at ICL-induced DSBs. Thus, when the FA pathway is defective, WRN helicase inhibition perturbs the normal ICL response, leading to NHEJ activation. Potential implication for treatment of FA-deficient tumors by their sensitization to DNA cross-linking agents is discussed.

Keywords: Werner syndrome, Fanconi Anemia, helicase, small molecule, DNA repair

INTRODUCTION

Werner syndrome (WS), characterized by premature aging and cancer predisposition (1), is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in WRN (2), encoding a RecQ DNA helicase-nuclease implicated in genomic stability (3, 4). WRN helicase can unwind key HR DNA intermediates and interacts with proteins implicated in DNA replication, recombinational repair, and telomere maintenance (5). WS cells are sensitive to certain DNA damaging agents, and display defects in resolution of recombination intermediates and a prolonged S-phase (6). WRN is required for normal replication fork progression after DNA damage or fork arrest (7).

WS cells are sensitive to ICL-inducing agents (8), and undergo apoptosis in S-phase (9). Cellular studies suggest WRN helicase, in conjunction with BRCA1, is required to process DNA ICLs (10). WRN is required for ATM activation and the intra-S phase checkpoint in response to ICL-induced DSBs (11), suggesting WRN and ATM collaborate in response to collapsed forks at ICL-induced DSBs. Biochemical studies using a reconstituted system with a DNA substrate harboring a psoralen ICL suggested that WRN helicase is required for ICL processing (12).

FA patients suffer from progressive bone marrow failure and cancer predisposition, and their cells (like WS cells) are sensitive to ICL agents, only to a greater extent (13). In fact, a chromosome breakage test using FA patient cells exposed to an ICL-inducing agent is used as a primary diagnostic tool for FA (14). The FA pathway is involved in initial recognition and unhooking of an ICL and subsequent repair of the ICL-induced DSB in conjunction with HR or translesion synthesis pathways, but the detailed molecular mechanism is an active area of investigation (15). One function of the FA pathway is to channel DSBs through the HR pathway, thereby preventing inappropriate engagement of breaks by error-prone NHEJ (16, 17). However, the relationship between DNA repair pathways is complex, as evidenced by a recent mouse study showing that deletion of 53BP1 or Ku exacerbates genomic instability in FANCD2-deficient cells (18).

To understand the role of WRN in the ICL response, we examined effects of a small molecule WRN helicase inhibitor in a FA mutant genetic background. A more potent structural analog of the previously identified parent compound NSC 19630 (19) was discovered that is blocked from potential thiol reactivity but retains the ability to modulate WRN function in vivo. The WRN helicase inhibitor NSC 617145 acted synergistically with a very limited concentration of MMC to induce DSB accumulation and chromosomal abnormalities, and activate the DNA damage response in FA mutant cells. NSC 617145 exposure resulted in enhanced accumulation of DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci and Rad51 foci in MMC-treated FA-deficient cells, suggesting that WRN helicase inhibition prevents processing of Rad51-mediated recombination products and activates NHEJ. WRN helicase may be a suitable target for chemotherapy strategies in FA-deficient tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture

HeLa (CCL-2), U2OS (HTB96), and HCT116 (CCL-247) cell lines were obtained from ATCC where they were tested and authenticated. HCT116 p53 double knockout cells were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins Univ) where they were tested and authenticated (20). All these cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine at 37 °C in 5% CO2. PSNF5 (BLM corrected) and PSNG13 (BLM mutant) are isogenic cell lines that were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. I. Hickson (Univ Copenhagen) where they were tested and authenticated (21, 22). PSNF5 is a stable BS cell line expressing a FLAG epitope-tagged, wild-type BLM protein from the CMV promoter in a pcDNA3-based construct. PSNG13 is a control BS cell transfectant containing the pcDNA3 vector only. The BLM mutant and corrected cell lines were grown in the same media as HeLa cells but supplemented with 350 μg/ml G418. The simian virus 40-transformed FA mutant fibroblasts, PD20 (FA-D2), GM6914 (FA-A), and their respective corrected counterparts were provided by Fanconi Anemia Cell Repository at Oregon Health & Science University where they were tested and authenticated. FA mutant and corrected cells were grown in the same medium as HeLa cells but supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml puromycin.

Cell proliferation assays

Proliferation was measured using WST-1 assay (Roche) as described (19).

siRNA transfection and Western blot analysis

WRN siRNA (WH: 5′ UAGAGGGAAACUUGGCAAAUU 3′ and/or CG: 5′ GUGUAUAGUUACGAUGCUAGUGAUU 3′) and control siRNA (19) was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Cells were plated to 50–60% confluence in 10-cm dishes 24 hours prior to transfection. siRNA (0.6 nmol) was mixed with 30 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in 3 ml of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). The mixture was added to cells which were subsequently incubated for 6 hours. After 24 hours, a second transfection was performed similarly. Seventy-two hours after the initial transfection, cells were harvested for preparing lysate or treated with small molecule compounds or DMSO at the indicated concentrations and cell proliferation was measured using WST-1 reagent (Roche) as described for HeLa cells. For FA mutant cells, siRNA transfection and treatment with NSC 617145 was performed as described above except that OD450 was measured after 48 hours of treatment with MMC, and/or NSC 617145.

For lysate preparation, cells were washed twice with 1X PBS. RIPA buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM EDTA) was added to the cells and the cells were incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Cells were scrapped and the suspension was further incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Cell suspension was centrifuged at 18,500 x g for 10 minutes at 4 °C and supernatant was collected. Twenty μg of the lysate was loaded on 8–16% SDS-PAGE. Protein was transferred onto a PVDF membrane and blot was probed with anti-WRN mouse monoclonal antibody (1:1000, Spring Valley Labs). For secondary antibody peroxidase labeled anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Vector) was used. Blot was developed using ECL Plus Western Blot Detection Kit as per manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham). As a loading control, blot was stripped and then re-probed with anti-actin antibody (1:5000, Sigma).

Analysis of metaphase chromosomes

Cell harvest and metaphase slide preparation was performed for metaphase analysis as described (23).

See Supplementary Material for additional information.

RESULTS

Inhibition of WRN helicase activity by small molecule NSC 617145

To identify small molecules that inhibit WRN helicase activity in a more potent manner than the previously identified compound NSC 19630 (19), we selected four close structural analogs and three compounds whose pattern of activity in the NCI60 screen matched NSC 19630 for analysis (Fig. S1). One of the latter compounds, NSC 617145, is also a structural analog, but blocked with respect to thiol reactivity in the five-membered rings by Cl atoms. NSC 617145 inhibited WRN helicase activity in a concentration dependent manner in vitro (Fig. S2A), yielding an IC50 value of 230 nM. NSC 617145 inhibited WRN ATPase in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S2B). No detectable effect on WRN exonuclease was observed (Fig. S2C).

To examine specificity of WRN helicase inhibition, we tested 5 μM NSC 617145 (~20-fold >IC50 value) on DNA unwinding catalyzed by various helicases. No significant inhibition of unwinding was observed with BLM, FANCJ, ChlR1, RecQ, and UvrD, and only a very modest (7%) inhibition of RECQ1 (Fig. S2D).

To determine their potency in vivo, HeLa cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of selected analogs or DMSO for 0–3 days. Of the selected analogs, NSC 617145 showed maximal inhibition of proliferation (98%) at the lowest concentration of NSC 617145 (1.5 μM) (Fig. 1A, Fig. S3). To address if the effect was cytostatic or cytotoxic, HeLa cells were exposed to NSC 617145 for three days, replenished with media lacking NSC 617145, and allowed to recover for 0–3 days (Fig. 1B). The lack of recovery from NSC 617145 suggested a cytotoxic effect. To determine if the effect of NSC 617145 was WRN-dependent, we compared its effect on HeLa cells depleted of WRN (≥90%) with NS-siRNA transfected cells. WRN-depleted cells grown in the presence of 1.5 μM NSC 617145 were resistant to its anti-proliferative effects, whereas NS-siRNA HeLa cells were highly sensitive to NSC 617145 (Fig. 1C). These results were confirmed by two different WRN-siRNA molecules which independently conferred resistance to NSC 617145 (Fig. S4). Western blot analyses demonstrated that WRN depletion by either WRN-siRNA or combination was >90% (Fig. S4).

Figure 1. NSC 617145 inhibits cell proliferation in a WRN-specific manner.

Panel A, HeLa cells were treated with DMSO or indicated NSC 617145 concentration for 0–3 days. Panel B, HeLa cells were exposed to 1.5 μM NSC 617145 for 3 days, replenished with media lacking NSC 617145, and allowed to recover for 0–3 days. Panel C, HeLa cells either untransfected (HeLa), transfected with non-specific siRNA (NS siRNA) or WRN specific siRNA (WRN siRNA) were treated with DMSO or 1.5 μM NSC 617145 for indicated number of days. Cell proliferation was then determined with WST-1 reagent. Percent proliferation was calculated. Experiments were repeated three times, and error bars indicate standard deviation. This applies to all figures.

NSC 617145 may exert its effect through a mechanism in which the NSC 617145-inhibited WRN helicase induces greater damage by interfering with a compensatory mechanism(s). To determine if the effect of NSC 617145 is dependent on a helicase-active version of WRN, HeLa cells were depleted of endogenous WRN, and siRNA-resistant WRN (wild-type or helicase inactive K577M (24)) was expressed. The resulting cells were tested for sensitivity to NSC 617145. It was observed that the WRN-depleted cells rescued with wild-type WRN were sensitive to the WRN helicase inhibitor compared to empty vector transfected cells, supporting the finding that the inhibition of cell proliferation by NSC 617145 is WRN-dependent (Fig. S5). However, WRN-depleted cells expressing the helicase inactive WRN-K577M behaved similar to the WRN-depleted cells transfected with empty vector, suggesting they were resistant to the negative effect of WRN helicase inhibitor NSC 617145 on cell viability.

Since NSC 617145 inhibited proliferation of p53-inactivated HeLa cells, we examined its effect on proliferation of U2OS cells with wild-type p53. NSC 617145 (1.5 μM) inhibited U2OS proliferation by 80% after day 2 (Fig. S6A), suggesting the effect of NSC 617145 was not dependent on p53 status. We also tested a pair of isogenic p53 negative and p53 positive HCT116 cells for sensitivity to NSC 6171145 (1.5 μM). Both cell lines were sensitive to the compound; however, p53-deficient cells were two-fold more resistant than p53-proficient cells (Fig. S6B). Since NSC 617145 exerted a WRN-dependent effect on proliferation, we evaluated whether cells mutated for the sequence-related Bloom’s syndrome (BLM) helicase were sensitive. BLM-null and corrected cells displayed similar sensitivity to NSC 617145 (Fig. S6C), suggesting BLM does not play a role.

Cellular exposure to NSC 617145 causes accumulation of double strand breaks, blocked replication forks, and apoptosis

Since WRN deficient cells are defective in resolution of recombination intermediates (6), NSC 617145 inhibition of WRN helicase activity might result in DSBs at blocked replication forks. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of NSC 617145 on γ-H2AX foci, a marker of DSBs. Exposure of HeLa cells to 0.25 μM NSC 617145 elevated γ-H2AX foci ~18 fold compared with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. S7A, B). WRN-siRNA-treated HeLa cells showed a similar low number of γ-H2AX foci in NSC 617145-and DMSO-treated cells, suggesting that inhibition of WRN activity in vivo by NSC 617145 led to DSB accumulation in a WRN-dependent manner. H2AX phosphorylation can be induced by a wide range of phenomenon including DSBs; therefore, we examined the effect of NSC 617145 on 53BP1 foci, an independent marker of DNA damage (25). Cellular exposure to 0.25 μM NSC 617145 elevated 53BP1 foci 3.5-fold compared with DMSO-treated cells, confirming NSC 617145 induced DNA damage (Fig. S7C, D).

HeLa cells exposed to 1.5 μM NSC 617145 showed a 4-fold increase in apoptosis as compared to DMSO-treated cells (Fig. S8). WRN-depleted HeLa cells showed no difference in level of apoptosis in NSC 617145- and DMSO-treated cells, demonstrating WRN-dependent induction of apoptosis by NSC 617145. Failure to repair DNA damage would affect replication fork progression; therefore, we determined the effect of NSC 617145 on PCNA foci formation. HeLa cells exposed to 0.25 μM NSC 617145 showed an elevated number of PCNA foci (~22-fold) compared with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. S9A, B). In contrast, WRN-depleted cells showed similar levels of PCNA staining for NSC 617145- or DMSO-treated cells, suggesting WRN-dependent accumulation of stalled replication foci. Consistent with the PCNA induction, exposure of HeLa cells to NSC 617145 (1 μM) resulted in an increased population in S-phase compared to DMSO-treated cells (Fig. S10). We also observed from FACS analysis a sub-G1 fraction of NSC 617145-treated HeLa cells (data not shown), consistent with the induction of apoptosis by the WRN helicase inhibitor. WRN-depleted cells exposed to 1 μM NSC 617145 showed a similar percentage of cells in S-phase compared to DMSO-treated cells, suggesting that NSC 617145 induced prolonged S-phase in a WRN-dependent manner.

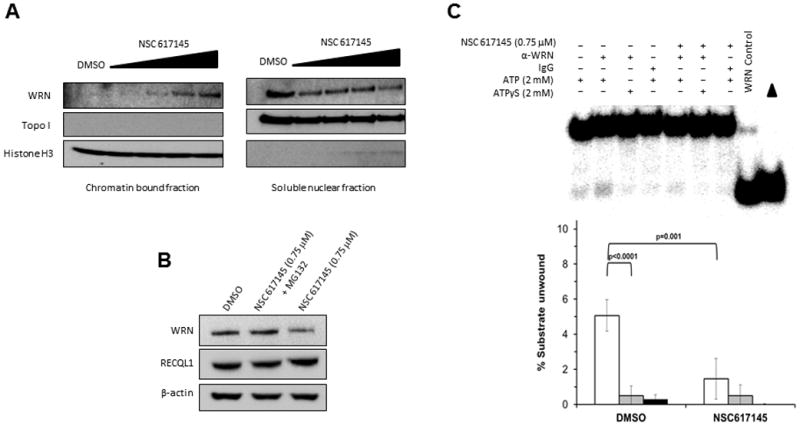

NSC 617145 induces WRN binding to chromatin and proteasomal degradation

We reasoned that NSC 617145 might target cellular WRN for helicase inhibition and induce toxic DNA lesions mediated by WRN’s interaction with genomic DNA, prompting us to ask if poisoned WRN became enriched in the chromatin fraction. Western blot analysis of nuclear soluble and chromatin-bound fractions prepared from HeLa cells exposed to NSC 617145 demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in WRN bound to chromatin (Fig. 2A). We also observed that the amount of WRN from extract of HeLa cells exposed to NSC 617145 (0.75 μM) for 6 hours was reduced compared to DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 2B). Inclusion of proteasome inhibitor MG132 restored WRN level to that of DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 2B). Thus, NSC 617145 causes WRN to become degraded by a proteasome-mediated pathway. Consistent with reduction of WRN protein in NSC 617145 treated cells, helicase activity catalyzed by immunoprecipitated WRN from an equivalent amount of total extract protein from HeLa cells treated with NSC 617145 (0.75 μM, 4 h) was reduced 4-fold compared to helicase activity by immunoprecipitated WRN from DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. NSC 617145 induces WRN to bind chromatin and WRN degradation.

Panel A, HeLa cells were exposed to increasing concentrations (0.75, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 μM) of NSC 617145 for 4 hours. Chromatin-bound and nuclear soluble fractions were prepared and 10 μg of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by analysis for WRN protein by immunoblotting. A representative Western blot from one of three independent experiments is shown. Histone H3 and TopoI served as markers for the chromatin and soluble nuclear fractions, respectively. Panel B, Whole cell extracts were prepared from HeLa cells exposed to NSC 617145 (0.75 μM) or DMSO for 6 hours and proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis for WRN. As indicated, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) was added to the cell culture at the same time as NSC 617145. Beta actin and RECQL1 served as a loading control. Panel C, Immunoprecipitated WRN obtained from an equivalent amount of protein derived from extracts of HeLa cells that had been exposed to 0.75 μM NSC 617145 or DMSO for 4 hours was tested for helicase activity on a forked duplex DNA substrate as described in Experimental Procedures. A representative helicase gel and quantitative data from at least three independent experiments are shown.

Synergistic effect of NSC 617145 and DNA cross-linking agent MMC on cell proliferation

We sought to use the newly identified WRN helicase inhibitor as a tool to explore if WRN helicase activity helps cells cope with stress imposed by the DNA cross-linking agent MMC. Treatment with either NSC 617145 (0.5 μM) or MMC (9.4 nM) exerted no significant effect on proliferation. However, co-treatment with both NSC 617145 (0.5 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) resulted in a 45% reduction in proliferation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, treatment with NSC 617145 (0.5 μM) and hydroxyurea (HU) (0–5 mM) had a similar effect on proliferation compared to HU alone (Fig. S11A), suggesting the apparent synergism between NSC 617145 and MMC is not a general effect imposed by other forms of replicative stress such as HU that depletes the nucleotide pool.

Figure 3. NSC 617145 exposure enhances sensitivity of FA mutant cells to MMC in a WRN-dependent manner.

Panel A, HeLa cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.5 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 3 days. Panel B, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Panel C, FA-A−/− and FA-A+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.75 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Panel D, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells lines transfected with WRN siRNA were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Panel E, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells lines transfected with NS siRNA were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Cell proliferation was determined. Percent proliferation was calculated.

NSC 617145-treated FA mutant cells are hypersensitive to MMC

Based on the synergistic effect of NSC 617145 and MMC, we hypothesized that WRN might participate in a pathway that is partially redundant with FA-mediated ICL repair. For this, we examined sensitivity of FA-D2 mutant and corrected cells to MMC and NSC 617145. Dose response curves for MMC and NSC 617145 sensitivity of FA-D2 cells indicated drug concentrations at which only modest effects on proliferation were observed (Fig. S11B, C). NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) or MMC (9.4 nM) exerted only a mild effect on cell proliferation; however, a significant 45% reduction was observed for cells treated with both NSC 617145 and MMC (Fig. 3B). In contrast, FA-D2+/+ cells showed only a 10% reduction of proliferation by combined treatment of NSC 617145 and MMC (Fig. 3B). Sensitization of FA-D2−/− cells to MMC by WRN helicase inhibition is distinct from the effect imposed by a deficiency or inhibition of proteins in the NHEJ pathway (LIG-4, Ku-70), which suppress ICL-sensitivity of FA-deficient cells (16, 17).

Combinatorial treatment of FA-A−/− cells with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) resulted in 60% reduction in proliferation compared to very modest effects exerted by either agent alone (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the effect was dependent on FANCA status since only 10% reduction in proliferation was observed for FA-A+/+ cells exposed to both MMC and NSC 617145. Thus, NSC 617145 acts in a synergistic manner with MMC in either the FANCA or FANCD2 mutant background.

Treatment with both NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and HU (0 – 1.25 mM) resulted in a very similar effect on proliferation as compared to HU alone in both FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells (Fig. 11D, E). Pretreatment of FA-D2−/− cells with HU for 24 hours followed by exposure to 0.125 μM NSC 617145 for 48 hours also showed very similar inhibition of proliferation compared to cells only exposed to HU (Fig. S11F), indicating NSC 617145 does not sensitize cells to HU.

NSC 617145 causes FA-D2 mutant cells to be hypersensitive to MMC in a WRN-dependent manner

To determine if enhanced MMC sensitivity of FA-D2−/− cells was mediated through inhibition of WRN function by NSC 617145, WRN was depleted by RNA interference in FA-D2−/− or FA-D2+/+ cells by ≥90% compared to NS-siRNA cells (data not shown). WRN-depleted FA-D2−/− cells grown in the presence of 0.125 μM NSC 617145 and 9.4 nM MMC were resistant to the anti-proliferative effects of combined treatment (Fig. 3D), whereas NS-siRNA FA-D2−/− cells were sensitive to co-treatment with NSC 617145 and MMC, as evidenced by 40% reduction in proliferation (Fig. 3E). In contrast, no difference in proliferation was observed with WRN depleted or NS-siRNA treated FA-D2+/+ cells co-treated with these NSC 617145 and MMC concentrations (Fig. 3D, E). Furthermore, WRN depletion in FA-D2−/− cells did not affect MMC sensitivity as compared to NS-siRNA treated or untransfected cells (Fig. S12), suggesting WRN helicase inhibition by NSC 617145 interfered with the ability of FA-D2−/− cells to cope with MMC-induced DNA damage.

NSC 617145 and MMC act synergistically to induce DNA damage and activate ATM

Failure to repair DNA ICLs in dividing cells would be expected to result in blocked replication forks and hence DSBs. Co-treatment of FA-D2−/− cells with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) resulted in a substantial increase in percentage (80%) of cells with >15 γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 4A). In contrast, only 30% FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to NSC 617145 and MMC showed >15 γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 4B). The difference in sensitivity of FA-D2−/− versus FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to very low concentrations of either MMC or WRN inhibitor was modest (NSC 617145) or hardly apparent (MMC) compared to the co-treatment. Thus, accumulation of MMC-induced DNA damage in FA-D2−/− cells is increased by NSC 617145.

Figure 4. Increased accumulation of γ–H2AX foci in FA-D2 mutant cells co-treated with NSC 617145 and MMC.

Panel A, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Cells were stained with anti-γ–H2AX antibody or DAPI, and imaged. Panel B, Percentage of cells with γ–H2AX foci (≤15 or >15, as indicated).

Exposure of FA-D2−/− cells with a dose range (0.125 μM – 1.5 μM) of NSC 617145 led to activation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) as detected by pATM-Ser1981 at 0.5 μM NSC 617145 (Fig. S13); however, no significant activation of ATM was observed at lower doses. In FA-D2+/+ cells, no appreciable ATM activation was detected except at the highest NSC 617145 concentration tested, 1.5 μM. Upon co-exposure of FA-D2−/− cells with a very low dose of NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM), there was a significant accumulation of pATM-Ser1981, whereas ATM activation was not detected in FA-D2+/+ cells (Fig. 5A). FA-D2−/− cells exposed to very low dose of NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) retained high levels of pATM-Ser1981 even after 24 h exposure (data not shown), suggesting a significant delay in damage repair when WRN helicase was inhibited. Thus, NSC 617145 and MMC act synergistically to induce DNA damage and activate ATM.

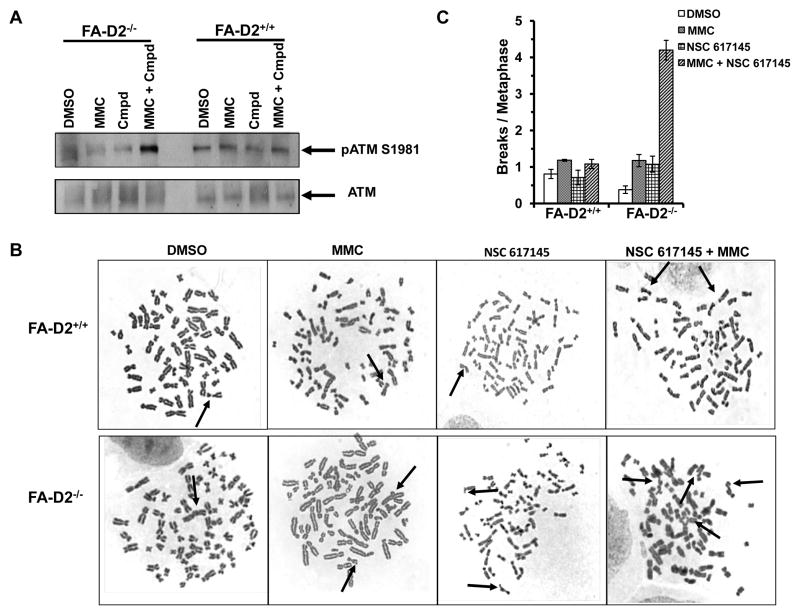

Figure 5. FA-D2 mutant cells co-treated with NSC 617145 and MMC display ATM activation and increased chromosomal instability.

Panel A, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+cells were co-treated with 0.125 μM NSC 617145 and 9.4 nM MMC for 3 hours. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting by using anti-pATM Ser1981 antibody. As a control, blot was reprobed with anti-ATM antibody. Arrow indicates phosphorylated ATM. Panel B, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Chromosome spreads were analyzed. Arrow indicates chromatid break, chromatid loss, or radial. Each radial is counted as equivalent to two chromatid breaks. Panel C, Chromatid breaks per metaphase.

NSC 617145 elevated MMC-induced chromosomal instability and induced accumulation of DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci in FA-D2 mutant cells

Recent studies suggest the FA pathway plays an important role in preventing aberrant DNA repair (16, 17). Since NHEJ factors have high affinity for DNA ends (26), the accumulated DSBs in FA-D2−/− cells when WRN helicase activity is pharmacologically inhibited might promote genomic instability when captured by error-prone pathways. To address this, we examined metaphase spreads from FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells for chromosomal aberrations (27) (Fig. 5B). FA-D2−/− cells exposed to NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) showed a 4-fold increase in abnormal chromosome structures compared to either agent alone (Fig. 5C). Enhanced chromosomal instability was dependent on FANCD2 status as evidenced by the relatively low level of chromosomal breaks in FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to NSC 617145 and/or MMC.

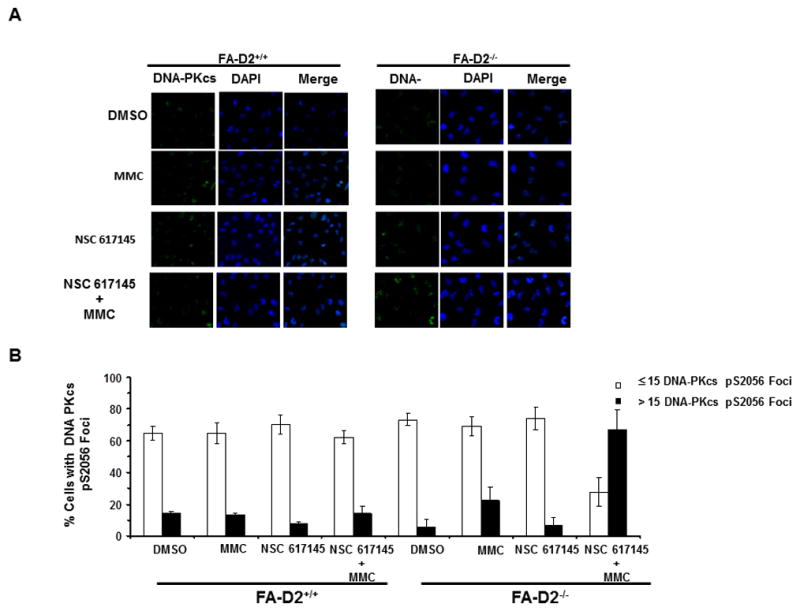

DNA-PK complex is required for NHEJ in conjunction with Ku70/80 and XRCC4/Ligase IV; moreover, DNA-PKcs pS2056 is detected at DSBs (28). To substantiate the role of NHEJ in DSB processing when WRN helicase is inhibited, FA-D2−/− cells were examined for DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci formation. Co-treatment of FA-D2−/− cells with limited concentrations of NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) and MMC (9.4 nM) resulted in 70% of cells with >15 DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci (Fig. 6A, 6B). In contrast, only 15% of FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to NSC 617145 and MMC showed >15 DNA-PKcs pS2056 (Fig. 6A, 6B). The difference in sensitivity between FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to very low concentrations of either MMC or NSC 617145 was modest (MMC) or hardly apparent (NSC 617145) compared to co-treatment, suggesting that when WRN helicase activity is inhibited, FA-D2−/− cells show increased chromosomal instability due to more DSBs repaired by the error-prone pathway. Strikingly, FA-D2+/+ cells co-treated with MMC (9.4 nM) and NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) showed similar levels of DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci as individually treated or DMSO control cells (Fig. 6A, 6B), suggesting an important role for WRN helicase in processing of MMC-induced cross-links converted to DSBs when the FA pathway is defective.

Figure 6. NSC 617145 exposure elicits NHEJ pathway in FA deficient cells upon co-treatment with MMC.

Panel A, FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Cells were stained with anti-DNA-PKcs-pS2056 antibody, or DAPI (Panel A). Percentage of cells with DNA-PKcs-pS2056 foci (≤15 or >15, as indicated) is shown (Panel B).

NSC 617145 exposure results in accumulation of Rad51 foci in FA-D2 mutant cells

WRN plays a physiological role in resolution of Rad51-dependent HR products (6). Expression of dominant-negative Rad51 or bacterial resolvase protein RusA could suppress HR or lead to the generation of recombinants, respectively, resulting in improved survival of WRN−/− cells. Since Rad51 foci are formed at sites of ICL lesions independently of FA-D2 status (29), we reasoned that WRN helicase inhibition in MMC-treated FA-D2−/− cells might result in accumulation of HR intermediates. Therefore, we investigated the effect of NSC 617145 and MMC treatment on Rad51 foci formation in FA mutant and corrected cells. We did not observe any significant difference in percentage of cells that displayed Rad51 foci between FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+upon cellular exposure with MMC (9.4 nM), as reported previously at higher doses of MMC [(29)], or NSC 617145 (0.125 μM) (Fig. 7A, 7B). In both cell lines, approximately 50% showed Rad51 foci, similar to that observed for DMSO-treated cells. Co-treatment of FA-D2−/− cells with NSC 617145 and MMC resulted in 90% of cells staining positive for Rad51 foci. In contrast, FA-D2+/+ cells exposed to both agents showed a percentage of cells with Rad51 foci very similar to DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 7A, 7B). Collectively, these results suggest that MMC-induced DNA cross-links in FA-D2−/− cells exposed to WRN helicase inhibitor are converted to DSBs and the HR pathway is activated but HR intermediates fail to be subsequently resolved.

Figure 7. Increased accumulation of Rad51 foci in FA-D2 mutant cells co-treated with NSC 617145 and MMC.

FA-D2−/− and FA-D2+/+ cells were treated with NSC 617145 (0.125 μM), MMC (9.4 nM), or both compounds for 2 days. Cells were stained with anti-Rad51 antibody or DAPI (Panel A). Percentage of cells with Rad51 foci (≤15 or >15, as indicated) is shown (Panel B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered a new inhibitor of WRN helicase activity (NSC 617145) that negatively affects cell proliferation and induces DNA damage in a WRN-dependent manner. WRN depletion negates biological activity of NSC 617145, suggesting targeted WRN helicase inhibition interferes with normal cellular DNA metabolism. The synergistic effect of NSC 617145 and MMC was not observed for HU, suggesting that impairment of WRN helicase activity exacerbates the effect of MMC-induced DNA damage during replication but not an effect exerted by an agent (HU) that primarily induces replication stress. We employed the WRN helicase inhibitor to sensitize a FA mutant because mounting evidence points toward a pivotal role of the FA pathway to coordinate a robust ICL response when WRN is also likely to act. WRN helicase inhibition by NSC 617145 makes FA-A or FA-D2 cells highly sensitive to very low MMC concentrations that would otherwise be only marginally active in normal cells. Furthermore, the effect of combined MMC / NSC 617145 treatment is a consequence of a FA pathway deficiency rather than a defect in a specific FA gene.

The synergistic effect of NSC 617145 and MMC in the FA-D2 mutant was apparent by robust γ-H2AX staining, ATM activation, and increased chromosomal abnormalities. Moreover, accumulation of DNA-PKcs pS2056 foci suggests that FA-D2 cells attempted to deal with MMC-induced DSBs by error-prone NHEJ when WRN helicase was pharmacologically inhibited. This finding builds on previous evidence that the FA pathway plays an important role in preventing aberrant NHEJ-mediated repair (16, 17), and implicates a role of WRN helicase in repair pathway choice. In addition to its helicase-dependent role in recombinational repair, WRN may have a structural role to enable repair of MMC-induced DNA damage. This would be akin to the observation that a WRN helicase/exonuclease double mutant complemented the NHEJ defect of WRN−/− cells (30). Although experimental data suggest WRN participates in an alternative NHEJ repair pathway of DSBs induced by increased reactive oxygen species in chronic myeloid leukemia cells (31), it is unclear if this pathway is relevant to a role of WRN helicase to confer MMC resistance in FA deficient fibroblasts. Further studies will be necessary to evaluate whether an alternate end-joining pathway or HR is important for repair of MMC-induced lesions in the WRN helicase-inhibited condition.

We also observed Rad51 foci accumulation in FA-D2−/− cells co-treated with MMC and NSC 617145, suggesting that HR was activated and at least some DSBs were channeled into homology mediated repair. However, since WRN plays a role in resolution of HR intermediates (6), NSC 617145 inhibition of WRN helicase activity might lead to accumulation of HR structures. We observed phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs only under conditions of WRN helicase inhibition in FA-D2−/− cells, suggesting that NHEJ was elicited; however, the mechanism of DNA-PKcs recruitment is still unclear.

Development of helicase inhibitors such as NSC 617145 that possess chemical stability and lack of nonspecific reactivity to thiol and other functional groups may prove useful for study of compensatory DNA repair pathways dependent on DNA unwinding by WRN or related helicases. In addition to their utility as research tools, small molecular inhibitors of WRN and other helicases may be useful for development of anti-cancer strategies that rely on synthetic lethality for targeting tumors with pre-existing DNA repair deficiencies (32).

Demonstration that very low concentrations of the chemotherapy drug MMC are cytotoxic for FA mutant cells exposed to the helicase inhibitor may have implications for strategies that target FA DNA repair pathway deficient tumors. Certain sporadic head and neck, lung, ovarian, cervical, and hematological cancers are characterized by epigenetic silencing of wild-type FA gene expression (33). It is estimated that 15% of all cancers harbor defects in the FA pathway (34). A significant number of these tumors may become reliant on WRN or other helicases to deal with DNA damage such as strand breaks. WRN may be a suitable target for pharmacological inhibition to sensitize FA-deficient tumors to chemotherapy drugs such as DNA cross-linkers.

In addition to epigenetic silencing, loss of heterozygosity from an additional mutation in an FA gene in heterozygous carriers may lead to increased cancer risk later in life (33, 35). FA pathway deficient fibroblasts were found to be highly sensitive to silencing of ATM kinase (33). FANCG- and FANCC-deficient pancreatic tumor lines were sensitive to a pharmacological inhibitor of ATM, raising the possibility for an anti-cancer treatment. More recently, FA deficient cell lines were shown to be hypersensitive to inhibition of CHK1 kinase either by siRNA or a pharmacological inhibitor of CHK1 kinase activity (36). Unlike the hypersensitivity of FA deficient cells to CHK1 silencing or kinase inhibition, WRN depletion did not increase sensitivity of FA-D2−/− cells to MMC. This suggests that NSC 617145 exerted its effect through a dominant negative mechanism in which NSC 617145-inhibited WRN helicase induced greater damage by blocking compensatory mechanism(s). Inhibition of WRN or a related helicase by a small molecule may provide an alternative strategy for targeting FA deficient tumors that is unique from approaches such as targeting the CHK1 or ATM kinase response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by Intramural Research Program of National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, and National Cancer Institute, and Fanconi Anemia Research Fund (RMB).

We thank Fanconi Anemia Research Fund for FA-A and FA-D2 cell lines, and Dr. Ian Hickson (University of Copenhagen) for recombinant BLM protein and BLM−/− (PSNG13) and BLM+/+ (PSNF5) cells. We also acknowledge the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Shared Resource at Georgetown University, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center that is partially supported by NIH/NCI grant P30-CA051008.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FA

Fanconi Anemia

- DSB

double strand break

- HR

homologous recombination

- HU

hydroxyurea

- ICL

interstrand cross-link

- MMC

mitomycin C

- NHEJ

nonhomologous end-joining

- WRN

Werner syndrome protein

- WS

Werner syndrome

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Martin GM. Genetic syndromes in man with potential relevance to the pathobiology of aging. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1978;14:5–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu CE, Oshima J, Fu YH, Wijsman EM, Hisama F, Alisch R, et al. Positional cloning of the Werner’s syndrome gene. Science. 1996;272:258–62. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monnat RJ., Jr Human RECQ helicases: roles in DNA metabolism, mutagenesis and cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:329–39. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi ML, Ghosh AK, Bohr VA. Roles of Werner syndrome protein in protection of genome integrity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:331–44. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Doherty KM, Brosh RM., Jr Mechanisms of RecQ helicases in pathways of DNA metabolism and maintenance of genomic stability. Biochem J. 2006;398:319–37. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saintigny Y, Makienko K, Swanson C, Emond MJ, Monnat RJ., Jr Homologous recombination resolution defect in Werner syndrome. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6971–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.6971-6978.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidorova JM, Li N, Folch A, Monnat RJ., Jr The RecQ helicase WRN is required for normal replication fork progression after DNA damage or replication fork arrest. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:796–807. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poot M, Yom JS, Whang SH, Kato JT, Gollahon KA, Rabinovitch PS. Werner syndrome cells are sensitive to DNA cross-linking drugs. FASEB J. 2001;15:1224–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poot M, Gollahon KA, Emond MJ, Silber JR, Rabinovitch PS. Werner syndrome diploid fibroblasts are sensitive to 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide and 8-methoxypsoralen: implications for the disease phenotype. FASEB J. 2002;16:757–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0906fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng WH, Kusumoto R, Opresko PL, Sui X, Huang S, Nicolette ML, et al. Collaboration of Werner syndrome protein and BRCA1 in cellular responses to DNA interstrand cross-links. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2751–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng WH, Muftic D, Muftuoglu M, Dawut L, Morris C, Helleday T, et al. WRN is required for ATM activation and the S-phase checkpoint in response to interstrand crosslink-induced DNA double strand breaks. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3923–33. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, Kaur R, Lu X, Shen X, Li L, Legerski RJ. The Pso4 mRNA splicing and DNA repair complex interacts with WRN for processing of DNA interstrand cross-links. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40559–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Andrea AD, Grompe M. The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auerbach AD. Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat Res. 2009;668:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kee Y, D’Andrea AD. Expanded roles of the Fanconi anemia pathway in preserving genomic stability. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1680–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.1955310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamo A, Collis SJ, Adelman CA, Silva N, Horejsi Z, Ward JD, et al. Preventing nonhomologous end joining suppresses DNA repair defects of Fanconi anemia. Mol Cell. 2010;39:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pace P, Mosedale G, Hodskinson MR, Rosado IV, Sivasubramaniam M, Patel KJ. Ku70 corrupts DNA repair in the absence of the Fanconi anemia pathway. Science. 2010;329:219–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1192277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunting SF, Callen E, Kozak ML, Kim JM, Wong N, Lopez-Contreras AJ, et al. BRCA1 functions independently of homologous recombination in DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol Cell. 2012;46:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal M, Sommers JA, Shoemaker RH, Brosh RM., Jr Inhibition of helicase activity by a small molecule impairs Werner syndrome helicase (WRN) function in the cellular response to DNA damage or replication stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006423108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, Waldman T, Zhou S, Brown JP, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies SL, North PS, Dart A, Lakin ND, Hickson ID. Phosphorylation of the Bloom’s syndrome helicase and its role in recovery from S-phase arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1279–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1279-1291.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaymes TJ, North PS, Brady N, Hickson ID, Mufti GJ, Rassool FV. Increased error-prone non homologous DNA end-joining--a proposed mechanism of chromosomal instability in Bloom’s syndrome. Oncogene. 2002;21:2525–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlacher K, Wu H, Jasin M. A Distinct Replication Fork Protection Pathway Connects Fanconi Anemia Tumor Suppressors to RAD51-BRCA1/2. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray MD, Shen JC, Kamath-Loeb AS, Blank A, Sopher BL, Martin GM, et al. The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nat Genet. 1997;17:100–3. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–23. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunting SF, Nussenzweig A. Dangerous liaisons: Fanconi anemia and toxic nonhomologous end joining in DNA crosslink repair. Mol Cell. 2010;39:164–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deans AJ, West SC. DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:467–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen BP, Chan DW, Kobayashi J, Burma S, Asaithamby A, Morotomi-Yano K, et al. Cell cycle dependence of DNA-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation in response to DNA double strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14709–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohashi A, Zdzienicka MZ, Chen J, Couch FJ. Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (FANCD2) functions independently of BRCA2 and RAD51-associated homologous recombination in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14877–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Huang S, Lee L, Davalos A, Schiestl RH, Campisi J, et al. WRN, the protein deficient in Werner syndrome, plays a critical structural role in optimizing DNA repair. Aging Cell. 2003;2:191–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallmyr A, Tomkinson AE, Rassool FV. Up-regulation of WRN and DNA ligase IIIalpha in chronic myeloid leukemia: consequences for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Blood. 2008;112:1413–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aggarwal M, Brosh RM., Jr Hitting the bull’s eye: novel directed cancer therapy through helicase-targeted synthetic lethality. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:758–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy RD, Chen CC, Stuckert P, Archila EM, de l V, Moreau LA, et al. Fanconi anemia pathway-deficient tumor cells are hypersensitive to inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia mutated. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1440–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI31245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taniguchi T, D’Andrea AD. Molecular pathogenesis of Fanconi anemia: recent progress. Blood. 2006;107:4223–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hucl T, Gallmeier E. DNA repair: exploiting the Fanconi anemia pathway as a potential therapeutic target. Physiol Res. 2011;60:453–65. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CC, Kennedy RD, Sidi S, Look AT, D’Andrea A. CHK1 inhibition as a strategy for targeting Fanconi Anemia (FA) DNA repair pathway deficient tumors. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.