INTRODUCTION

Although evidence-based guidelines on the management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes have been widely published, implementation of recommended therapies is suboptimal.1 The effectiveness of national guidelines for the management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar, depends upon how well healthcare providers implement the recommended therapies and how well patients adhere to them. Optimizing adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors and prescribed drugs to manage cardiovascular risk factors is associated with better outcomes and may reduce healthcare costs.2, 3, 4

Nurse-led, team-based case management including community health workers (CHW), has been shown to be an efficacious strategy to improve CVD risk factors in our own and other studies.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Research also has demonstrated that nurse practitioners (NP) can provide primary care services of equivalent or better quality and at lower cost than similar services provided by other healthcare professionals.12, 13

This paper summarizes the outcomes and reports on the cost-effectiveness analysis of a program of CVD risk reduction delivered by NP/CHW teams versus enhanced usual care to improve lipids, blood pressure, and HbA1c levels in patients in federally-qualified metropolitan community health centers.

METHODS

Trial Design

Complete details of the design of the randomized trial, methods and main findings have been reported previously.8, 14 Briefly, the Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) study was a randomized controlled trial in which 525 patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: management of CVD risk factors by a NP/CHW team or an enhanced usual care (EUC) group. Patients in the EUC group received care from their primary provider which was enhanced by providing feedback on CVD risk factors to both the patients and their providers. Management by the NP/CHW team included tailored educational and behavioral counseling for lifestyle modification, pharmacologic management, and telephone follow-ups between visits.

Participants

Patients were recruited between July 2006 and July 2009 from two community health centers which are part of Baltimore Medical Systems Incorporated (BMS), a corporation of federally - qualified community health centers. Patients were identified from medical records using ICD 9 codes and were eligible if they had diagnosed CVD, type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, or hypertension. They had to be African American or Caucasian, ≥ 21 years of age and able to speak and understand English. In addition, they had to have at least one of the following criteria at the time of the medical record reviews: (1) an LDL-C ≥100 mg/dl or LDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dl if no diagnosed CVD or diabetes, (2) a blood pressure > BP 140/90 mm Hg or > 130/80 mm Hg if diabetic or renal insufficiency, or (3) if diabetic, a HbA1c 7% or greater or glucose ≥ 125 mg. Patients were excluded if they had a non-cardiac co-morbidity with a life expectancy of less than 5 years or if they had a serious psychiatric or neurological impairment that would prevent them from participating in their own care.

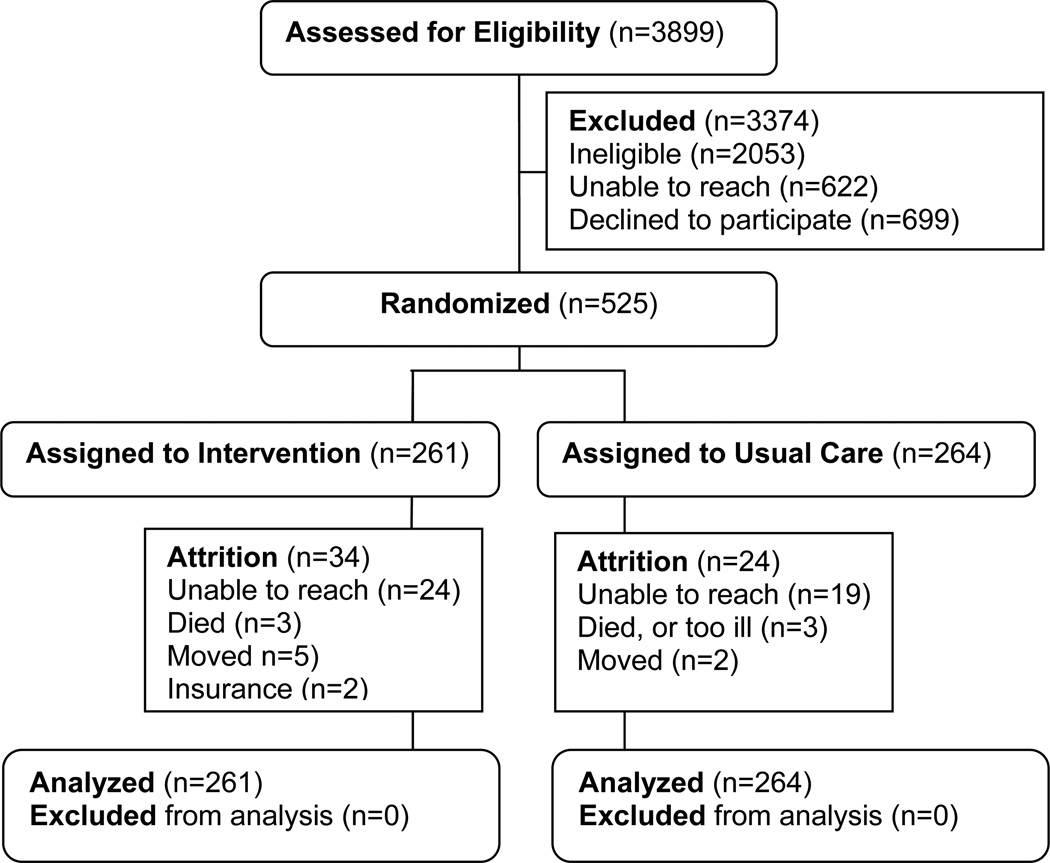

Of the 3899 screened for eligibility, 525 were enrolled in the trial (Figure 1). The participants were randomly assigned, stratified by ethnicity and sex, to receive the NP/CHW intervention or EUC. All participants provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

COACH Flow Diagram

Intervention

The NP/CHW intervention focused on evidence-based behavioral interventions to effect therapeutic lifestyle changes and adherence to drugs and appointments as well as the prescription and titration of drugs. The NP and CHW worked as a team and managed patients for one year. The NP functioned as the case coordinator for each patient. She managed the intervention plan, conducted the intervention including counseling for lifestyle modification, drug titration and prescription, supervised the CHW, and conferred with the physician. Patients also met with a CHW who reinforced instructions by the NP related to lifestyle modifications and drug therapies and assisted patients in designing strategies to improve adherence. The intensity of the NP/CHW intervention was based on the achievement of goals and was guided by study algorithms developed from national guidelines.8 (Algorithms available in Appendix for reference.)

Patients in the EUC group and their BMS providers received reports of baseline lipids, BP, and HbA1c along with recommended goal levels. Patients also received an American Heart Association pamphlet on controlling CVD risk factors.

Clinical Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were changes from baseline evaluation to one year follow-up evaluation in lipids, BP, and HbA1c. Total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured directly after a 12 hour fast. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was estimated using the Friedewald equation.15 If triglyceride levels were greater than 400 mg/dL, LDL-C was measured directly through ultracentrifugation methods. HbA1c was measured using high pressure liquid chromatography. Blood pressure was measured using the Omron Digital Blood Pressure Monitor HEM-907XL automatic blood pressure device according to JNC VII guidelines.16 The average of three blood pressures was noted.

Resource Use Measurement and Cost Assignment

The cost effectiveness evaluation was performed from a health services perspective. It was assumed that if a healthcare organization were to add these NP/CHW case management services, no additional office space and equipment would be necessary. Costs were not discounted since the time period of the intervention was one year. Costs that related to the process of the research rather than delivery of the intervention were not included.

Provider Costs

Nurse practitioner and CHW time spent delivering the intervention was collected for a sample of 30% of patients for one year. Patients in this sample were selected consecutively, beginning with a randomly selected patient. The NP and CHW recorded details of patient encounters, including the length of encounters to the closest minute and the types of activities carried out as part of the interventions such as medication counseling, lifestyle counseling, feedback on laboratory results, and physical examinations. They also captured time for preparation and followup activities related to the intervention but outside of the direct encounter with the patient. This non-encounter time included activities such as preparation for visits, documentation in the medical record, consultation with other health care providers, contacting the pharmacy or insurance agency. The number of visits during the year of intervention was also captured.

The NP and CHW salaries were based upon the standard wage rates in the 2010 Occupational Employment and Wages from the Bureau of Labor Statistics national estimates for the respective occupations17. The median hourly wage for NP’s (health diagnosing and treating practitioners) was $33.32 and for CHW’s (community and social services specialists) $18.32. Adjustments of an additional 30% for benefits resulted in a final hourly rate of $51.14 for the NP and $25.78 for the CHW.

To determine the costs of providing health care for the management of the same conditions in the usual care group, a chart review was completed on a random sample of 53 patients randomized to receive usual care. Data were collected on the number of visits to a Baltimore Medical System health care provider for the treatment of their cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes during the year of enrollment in the clinical trial. Expert opinion from the primary care practitioners estimated one hour to conduct the patient encounter and necessary follow-up documentation of these moderate to high intensity level visits. According to the national estimates, the mean hourly wage for family and general physicians was $83.59.17 Adding 30% for benefits the hourly wage for other healthcare provider visits was $108.67.

Laboratory Test Costs

The costs for laboratory tests used to monitor response and side effects of therapy over the year that patients were in the study were included in the calculations. A chart review of a random sample of 53 usual care patients and 53 intervention patients provided an average number of lipid panels, liver function tests, and hemoglobin A1C tests per patient. The laboratory costs for the tests used in the analyses were $36 for a lipid panel, $42 for liver function tests, and $35 for hemoglobin A1C.

Drug Costs

An annual per patient average estimate of drug costs was calculated for each group. Current cardiovascular, lipid-lowering, anti-hypertensive and diabetes drugs were identified by patient interview at 6 and 12 months. It was assumed that the patient was on the same drugs for the previous 6-month period. The categories included in these assessments were anti-hypertensive drugs, lipid lowering drugs, drugs to treat coronary artery disease, oral hypoglycemics and insulin. The cost of a 1-month supply of each drug was determined from the 2010 Drug Topics Red Book average wholesale price.18 This cost was multiplied by six (six months of drug) and added to the other six month cost to determine the annual cost for each drug. A total annual cost of all cardiac, hypertensive, lipid-lowering and diabetes drugs was calculated for each patient.

Statistical Methods

Primary outcome measures were analyzed with an intention-to-treat analysis. General linear mixed models were used to model each outcome variable as a function of time and intervention group controlling for age, sex, race, education, body mass index, insurance and an indicator of in-control for clinical outcome at baseline.

A clinician time cost for each patient was calculated by multiplying the average cost per hour of the practitioners’ time (NP and CHW for intervention group and other BMS primary care provider in usual care group) by the average time per visit by the average number of visits. This provider cost was added to the average total cost of drugs and laboratory testing to determine the average total costs per patient. Cost-effectiveness was calculated using four cost effectiveness ratios with the cost associated with the usual care group subtracted from the cost associated with the intervention group as the numerator and the clinical benefit (percent reduction in LDL-C; systolic and diastolic blood pressure; and HbA1c) in the usual care group subtracted from the clinical benefit in the intervention group as the denominator.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample was predominantly Black (79%) and female (71%). A majority of patients had annual incomes less than $20,000 in spite of having at least a high school education. Less than half had private health insurance. The groups were similar in sociodemographic and baseline measures except for higher HbA1c levels in the NP/CHW intervention group compared to the EUC group (Table 1). There was no statistically significant differential attrition between the two groups. Ninety four percent (n=467) completed the 1-year assessment with no differences between completers and non-completers in baseline lipids, HbA1c, BP, age, education, race, or sex.

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 261) |

Control (n = 264) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 54.3 (12.0) | 54.7 (11.5) | 0.692 |

| Female, n (%) | 187 (71.7) | 187 (70.8) | 0.837 |

| Black race, n (%) | 207 (79.3) | 210 (79.6) | 0.946 |

| < High School Education, n (%) | 76 (29.1) | 94 (35.6) | 0.051 |

| Private insurance, n (%) | 112 (42.9) | 105 (39.8) | 0.403 |

| < $20,000 Annual income, n (%) | 137 (52.5) | 149 (56.4) | 0.223 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mean (SD) | 83.1 (12.6) | 82.3 (13.0) | 0.442 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mean (SD) | 139.7 (23.8) | 138.7 (19.9) | 0.587 |

| LDL-C, mean (SD) | 121.6 (40.0) | 116.3 (40.5) | 0.132 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD) | 8.9 (2.2) | 8.3 (1.9) | 0.006 |

SD indicates standard deviation; LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol

Treatment

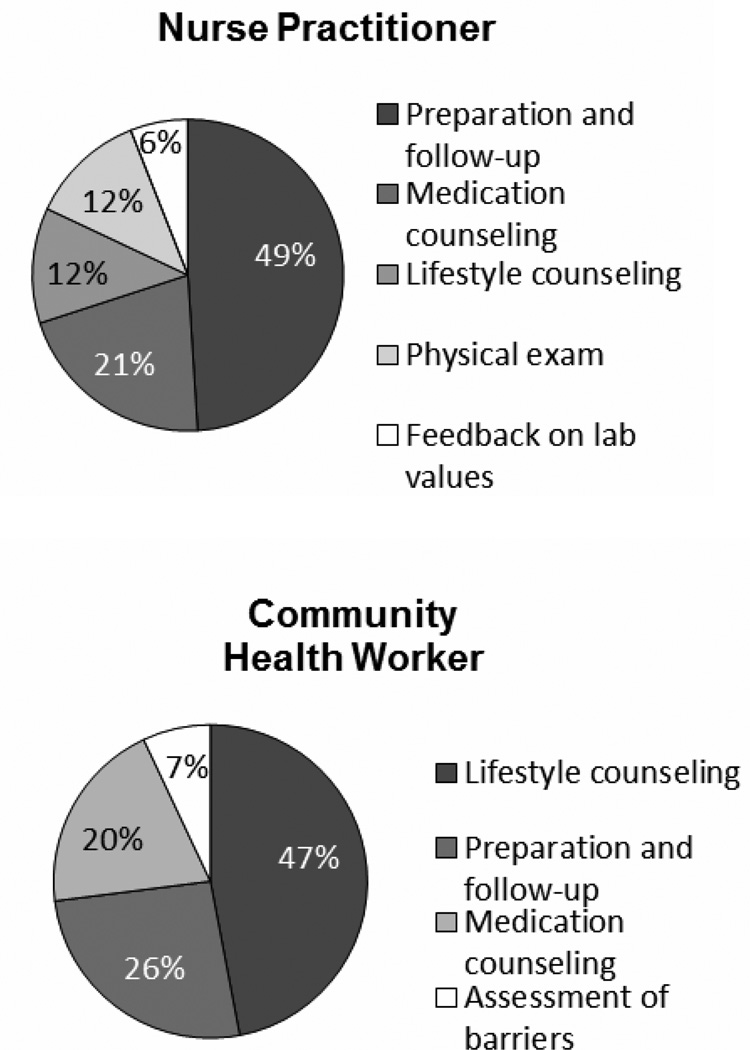

Over the course of the one year of intervention, patients had an average of 7.6 (6.9, 8.2) encounters with the NP and 5.3 (4.8, 5.9) encounters with the CHW. (Table 3) This is relative to the average of 2.8 (2.2, 3.5) of visits to other health care providers for cardiac or diabetes management in the usual care group. A total of 84 percent of patients randomized to the intervention group completed an initial visit, and 70 percent had at least four in-person visits with the nurse. Figure 2 details the percentage of time the NP and the CHW spent in the various activities that comprised the intervention. The NP averaged 17 (CI 16, 19) minutes per direct encounter time with the patient and another 16 (CI 14, 17) minutes for non-encounter activities. The highest percentage of time with the patient was spent in counseling regarding medications (43%), followed by lifestyle counseling (22%), physical examination (22%), and providing feedback about laboratory results (13%). A large majority (76%) of non-encounter time was spent in documentation, followed by preparation activities (17%) and coordination of care (7%). The CHW spent an average of 11 minutes per encounter which included in person and telephone follow-ups with a majority of her time focusing on lifestyle counseling (66%), followed by reinforcement of medication counseling (28%), and evaluation of barriers to control (6%). Documentation was the major focus of the CHW’s time outside of direct patient contact (70%).

Table 3.

Per Patient Use of Resources by Category for Each Arm

| Cost Category (95% CI) |

Enhanced Usual Care | NP/CHW Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory testing | ||

| # Tests | 5.4 (4.7, 6.2) | 11.5 (10.2, 12.8) |

| Cost ($) | 206 (179, 233) | 439 (390, 488) |

| Medication | ||

| # Meds | 3.7 (3.4, 4.0) | 4.3 (4.0, 4.6) |

| Cost ($) | 1684 (1447, 1921) | 2139 (1848, 2431) |

| NP Care | ||

| # Visits | 7.6 (6.9, 8.2) | |

| Cost ($) | 217(191, 243) | |

| CHW Care | ||

| # Visits | 5.3 (4.8, 5.9) | |

| Cost ($) | 34(30, 38) | |

| MD Care | ||

| # Visits | 2.8 (2.2, 3.5) | |

| Cost ($) | 308 (239, 377) | |

| Total Cost ($) | 2198 (1960, 2450) | 2825 (2541, 3132) |

CI indicates Confidence Interval; NP Nurse Practitioner; CHW Community Health Worker

Figure 2.

Percentage of intervention time by task

At 12 months, patients in the intervention group had significantly greater overall improvement in LDL cholesterol, systolic and diastolic BP, and HbA1c compared to patients receiving EUC (Table 2). The estimated between group differences were statistically and clinically significant. At the 12 month follow-up, a significantly higher percentage of patients in the intervention group compared to the EUC group had values that reached guideline goals or showed clinically significant improvements in LDL cholesterol (EUC=58%; I=75%, p<0.001), systolic BP (EUC=74%; I=82%, p=0.018), and HbA1c (EUC=47%; I=60%, p=0.016).

Table 2.

Changes in Primary Outcomes by Group

| Outcome | Intervention Group (n=261) |

Usual Care Group (n=264) |

P Value* | Estimated Between Group Difference (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Change | |||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | ||||||

| Baseline | 139.7±23.8 | 8.9±25.1 | 138.7±19.9 | 2.7±22.0 | 0.003 | −6.2 (−10.2, −2.1) |

| One year | 130.8±20.7 | 135.9±20.5 | ||||

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | ||||||

| Baseline | 83.0±12.7 | 5.6±13.6 | 82.3±13.0 | 2.6±12.1 | 0.013 | −3.1 (−5.3, −0.9) |

| One year | 77.4±12.5 | 79.7±12.6 | ||||

| LDL†, mg/dL | ||||||

| Baseline | 121.6±40.0 | 21.6±44.0 | 116.3±40.5 | 5.7±38.9 | <0.001 | −15.9 (−23.0, −8.8) |

| One year | 100.1±39.2 | 110.6±36.8 | ||||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | ||||||

| Baseline | 8.9±2.2 | 0.6±2.3 | 8.3±1.9 | 0.1±1.8 | 0.034 | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.2) |

| One year | 8.3±2.2 | 8.2±2.1 | ||||

Intention to treat analysis using general linear mixed model with group, time, groupxtime effects and covariates age, sex, race, education, body mass index, insurance and an indicator of in-control for clinical outcome at baseline.

To convert total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113.

Cost-Effectiveness

Resources used per patient by arm are presented in Table 3. The increase in laboratory testing and medications in the more intensive intervention arm are apparent, contributing to the increased overall cost of the intervention compared to the cost for usual care. Although patients in the intervention arm were on average taking less than one additional medication compared to those in the usual care arm, the drugs of patients in the intervention arm were more likely to be titrated to a higher dosage which likely contributed to better efficacy but also significantly more expense. In addition, closer monitoring according to guideline recommendations, lead to an increased number of laboratory tests in the intervention group. The total cost for one year of intervention from the NP/CHW team exceeded the cost for MD care; however, the average per patient incremental total cost (NP/CHW - MD) was only $627 (248, 1015).

The cost-effectiveness ratios are presented in Table 4. The cost-effectiveness of the one year intervention was $157 for every one percent drop in systolic blood pressure and $190 for every one percent drop in diastolic blood pressure; $149 per one percent drop in HbA1c; and $40 per one percent drop in LDL-C. The costs for every unit drop in outcome were similar except for HbA1c, with a cost of $1255 for a drop of one unit (i.e. from 8% to 7%).

Table 4.

Cost Effectiveness Ratios for One Year of Intervention

| Cost for every % drop |

Cost for every unit drop |

|

|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP | $157 | $101 |

| Diastolic BP | $190 | $209 |

| LDL-C | $40 | $39 |

| HbA1c | $149 | $1255 |

DISCUSSION

Comprehensive management of cardiovascular risk factors by NP/CHW teams that includes lifestyle counseling, drug prescription and titration and promotion of compliance is a cost-effective strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk and thereby address health disparities in underserved, minority populations. Chronic illness care in medically underserved patients with CVD or at high risk for CVD is complex. These data add to the body of evidence that specially trained nurse-led teams are efficacious strategies to improve management. A sizeable body of research reinforces that patient care outcomes are similar and sometimes better when patients are managed by NP’s as primary care providers as compared to physicians.19 As the costs of health care for chronic diseases continues to increase, NPs are in pivotal positions to address the need for safe, effective, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable health care.20

This study also provides evidence that a nurse-led team which includes CHWs is an effective model of care. Community health workers are critical members of these teams. They share perspectives and experiences that enhance trust enabling them to effectively bridge communication gaps between patients and healthcare providers and intervene to decrease barriers to adherence. However, adoption and sustainability of this model of care will require financing mechanisms for CHWs. Funding, reimbursement and payment policies for CHWs must be established to ensure that CHW models are adopted in mainstream health care.21, 22

While it is atypical to have four separate cost-effectiveness ratios in a single study, the relatively low incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for each outcome suggests that the effect of any one of the clinical changes may be sufficient to offset the costs. With all four changes simultaneously this would only amplify the individual economic outcomes. The relatively small incremental cost for the additional benefit of LDL-C, blood pressure and HbA1C lowering seen in the NP/CHW group could yield meaningful downstream differences in morbidity and mortality from CHD. Clinical trials with statin lipid-lowering drugs in patients indicate that a 1% decrease in LDL-C reduces risk for CHD by about 1%.23 The benefit is even greater in those with existing CHD or diabetes, a CHD equivalent, decreasing stroke rates, improving angina and myocardial perfusion, and decreasing the need for subsequent revascularization.23 Stamler and colleagues estimated that a five mmHg reduction of systolic blood pressure in the adult population would result in a 14 percent overall reduction in mortality due to stroke.24

In conclusion, this study supports NP/CHW teams using evidence-based treatment algorithms as a cost-effective, successful strategy to implement national guidelines for the management of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes in high risk vulnerable populations. This is particularly relevant as we plan for the release of new national guidelines in 2013.

Over the next five years, the Affordable Care Act legislation will be infusing 11 billion dollars into community health centers such as the Baltimore Medical Systems.25 Nurse practitioner and community health workers are underutilized resources who should be incorporated into this healthcare reform to increase the quality of care and improve patient outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. The results of this trial also support the potential for nurse-led patient-centered medical homes to improve the quality of care in high risk underserved populations.

What’s New?

Comprehensive management of cardiovascular risk factors by NP/CHW teams that includes lifestyle counseling, drug prescription and titration and promotion of adherence is a cost-effective strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk.

Nurse practitioner and community health workers are underutilized resources who should be incorporated into healthcare reform to increase the quality of patient-centered care and address health disparities in underserved, minority populations.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully thank the patients who participated in the program and the administration and staff of Baltimore Medical Systems for their collaboration in the design and implementation of the program. We also thank Carol Curtis for her coordination of the research and assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Sources: This study was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health grant # R01HL082638.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jerilyn K Allen, M Adelaide Nutting Professor of Nursing, Public Health and Medicine, Associate Dean for Research, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, 525 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21205, P: 410-614-4882, F: 410-614-1446, jallen1@jhu.edu.

Cheryl R Dennison Himmelfarb, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing and Medicine.

Sarah L Szanton, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

Kevin D Frick, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and School of Nursing.

Reference List

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi, et al. Effect of medication non-adherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muszbek N, Brixner D, Benedict A, Keskinaslan A, Khan Z. The economic consequences of noncompliance in cardiovascular disease and related conditions: a literature review. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(2):338–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01683.x. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen JK. Cholesterol management: an opportunity for nurse case managers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2000;14(2):50–58. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen JK, Blumenthal RS, Margolis S, Young DR, Miller ER, III, Kelly K. Nurse case management of hypercholesterolemia in patients with coronary heart disease: results of a randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2002;144(4):678–686. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.124837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen JK, Dennison CR. Randomized trials of nursing interventions for secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure: systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(3):207–220. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181cc79be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen JK, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: a randomized, controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(6):595–602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(11 Pt 1):906–913. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker DM, Raqueno JV, Yook RM, et al. Nurse-mediated cholesterol management compared with enhanced primary care in siblings of individuals with premature coronary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(14):1533–1539. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.14.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(9):721–729. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer JC. Nurse practitioners as an underutilized resource for health reform: Evidence-based demonstrations of cost-effectiveness. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2010;22:228–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newhouse R, Stanik-Hutt J, White K, et al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990–2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(5):230–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JK, Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, Bone L, Hill MN, Levine DM. COACH trial: A randomized controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers: Rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(3):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) [Accessed June 11, 2012]; NIH Publication No. 02-215 http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/hbp/bpmeasu.pdf Published April 19, 2002.

- 17.National Compensation Survey: Occupational Earnings in the United States. Bulletin 2753. [Accessed June 11, 2012];U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ncswage2010.htm Published May 20, 2010.

- 18.Murray L, Reed J. Red Book - Pharmacy’s Fundamental Reference. Montvale, NJ: PDR Network, LLC, Thomas Reuters; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurant LM, Reeves D, Hermmens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons Schram A. Medical Home and the Nurse Practitioner: A Policy Analysis. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2010;6(2):132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR, Hill MN, Levine DM. Community health workers as interventionists in research and practice for the prevention of heart disease and stroke. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2005;29(5S1):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dower C, Know M, Lindler V, O'Neil E. Advancing Community Health Worker Practice and Utilization: The Focus on Financing. [Accessed November 11, 2012]; http://futurehealth.ucsf.edu/Public/Publications-and-Resources/Content.aspx?topic=Advancing_Community_Health_Worker_Practice_and_Utilization_The_Focus_on_Financing. Published December 1, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report Circulation. 2002;106:3143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamler R. Implications of the INTERSALT study. Hypertension. 1991;17(1 suppl):16–20. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.1_suppl.i16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Community Health Centers: The Challenge of Growing to Meet the Need for Primary Care in Medically Underserved Communities. [Accessed july 17, 2012]; http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8380.pdf. Published October 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]