Abstract

Background

Advance care planning (ACP) is an under-utilized process that involves thinking about what kind of life-prolonging medical care one would want should the need arise, identifying a spokesperson, and then communicating these wishes.

Objective

To better understand what influences individuals to engage in ACP.

Design

Three focus groups using semi-structured interactive interviews were conducted with 23 older individuals from three diverse populations in central Pennsylvania.

Results

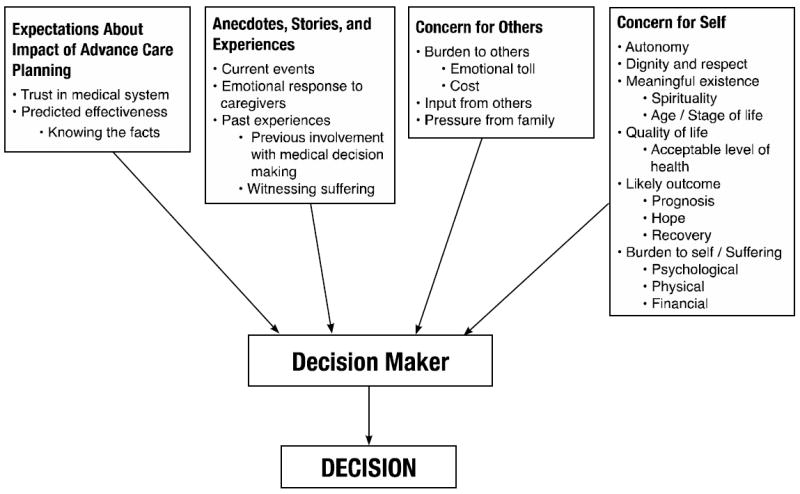

Four categories of influences for engaging in ACP were identified: 1) Concern for Self; 2) Concern for Others; 3) Expectations About the Impact of Advance Care Planning; and 4) Anecdotes, Stories, & Experiences.

Conclusions

The motivations for undertaking ACP that we have identified offer healthcare providers insight into effective strategies for facilitating the process of ACP with their patients.

Keywords: Advance care planning, Advance directive, Living will, End-of-life, Bioethics, Decision-making, Focus group

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is a complex process that requires a person to 1) think about what kind of life-prolonging medical care (if any) they wish to receive should the need arise; 2) create some means for communicating these wishes; and 3) identify a spokesperson to serve as their advocate should they become unable to speak for themself.1-5

Before people engage in ACP, they need to consider the process worthwhile, and the outcomes beneficial. Given the emotional significance of the subject, ambivalence is understandable. Studies show that few individuals have systematically considered the relevant issues and/or communicated their wishes to those who will need to make medical decisions for them;4, 6, 7 and only 15-35% of adults actually complete advance directives.8, 9 Much work has been done to identify reasons for low completion rates and barriers to effective ACP.10-20 Also, much is known about the mechanics and efficacy of ACP, 2, 4, 6, 10, 15, 17, 18, 21-27 the kinds of life-sustaining treatments patients prefer,7, 28-35 and what parts of ACP matter most to them.7, 16

Yet despite this growing literature, there is a paucity of data about what factors influence people to actually engage in ACP.36 Particular circumstances (e.g., a family member’s urging or witnessing end-of-life care gone wrong)23, 37-40 may prompt individuals to engage in ACP. But there are other reasons as well, and if healthcare providers are to systematically help patients take action, a more detailed understanding of motivational influences is needed.

This paper describes findings from focus group interviews that were part of a larger research project on end-of-life decision-making,41 which included asking participants to think about factors that influenced medical decisions around the end of life. During this inquiry, it became clear that before individuals would undertake the process of ACP, a certain set of motivations needed to be in place. Here, we begin to explore those motivations.

Methods

The study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R21 NR008539) and approved by the Penn State Hershey Medical Center Human Subjects Protection Office. Focus group methodology was chosen because small group interactions promote sharing of experiences, values, beliefs, and feelings to uncover areas of consensus or dissent, as well as their sources.42

Sample

Study participants were recruited from three distinct settings: 1) a suburban senior center serving a primarily white, elderly, middle class population; 2) an urban senior center serving a frail, underserved, African-American population; and 3) a breast cancer support group whose members had undergone treatment for breast cancer. From each of these groups, individuals whose health experiences would have raised ACP related concerns were specifically invited to participate. Consistent with standard focus group methodology, we chose small groups to optimize group interactions and to encourage open communication.43

Data Collection

Building on previous pilot work, the study team developed questions and prompts to generate discussion on the topic of interest (see Table 1), and then used semi-structured, interactive interviews to gather data.

Table 1.

Prompts used in focus groups to generate discussion.

| Questions for Prompting Discussion |

|---|

| 1. Have any of you had to make a really big decision about your health lately? |

2. Have you ever in your lifetime had to make a decision for somebody else?

|

| 3. Has anybody made up a living will, and what factors would you take into mind in doing so? |

| 4. Have you had to think about advance care planning in relation to yourself, and if so what was that like? |

| 5. What do you think about the kind of situation Terry Schiavo was in? |

| 6. How do your spiritual beliefs affect what you choose? |

Each focus group session lasted 60-90 minutes and was led by an experienced nurse researcher with extensive experience in facilitating focus groups (CD). At the start of each focus group, the facilitator explained the study’s purpose and obtained consent from each participant. Due to the sensitive nature of the discussion, options for follow-up with primary care providers or crisis intervention were provided in case a participant experienced undue emotional distress. (None did.) Each group discussion was taped, transcribed, and then checked for accuracy by the facilitator, before field notes were added to the transcripts.

Data Analysis

Two of the research team members (CD and MW) independently reviewed each transcript and created a coding schema that identified recurring themes related to the study question: “What influences or motivates patients to engage in advance care planning?” Using an iterative process, these initial reviewers independently coded the complete transcripts from each focus group and, after reaching saturation on identifying themes and assigning transcript data to them, met to compare results. Differences in coding were reconciled by: 1) discussion about the meaning of the code until agreement was reached, or 2) creation of a new code that captured the content of the statement. Once consensus was reached, a third independent coder reviewed the codes for validity. Subsequent coding discrepancies occurred in fewer than 10% of the comparisons, and all were reconciled successfully.

Following this validation, the entire study team met again to conceptualize categories that would capture commonly occurring themes. The entire study team then met and all categories (and theme assignments) were reconciled as per previously and consensus reached. For reliability purposes, contrary cases (i.e., statements that did not fit any category) were identified to strengthen the coding schema.

Results

Twenty-three individuals participated —suburban senior center (n=9); urban senior center (n=7); breast cancer support group (n=7). All participants were English speaking, lived in central Pennsylvania, and were over 50 years old. Participants’ mean age was 74 years (range 54-87), and 15/23 (65%) were female. Full demographic information is available for only 14 participants: 7/14 (50%) African-American; 9/14 (64%) educated through high school or less; and 4/12 (33%) previously completed an advance directive.

As a preliminary exploration into factors that influence individuals to engage in advance care planning (ACP), we focused on discrete categories of influence based on themes that emerged from the data. Had we recognized that these influences were actually motivators that led people to pursue ACP we might have been able to draw on more traditional models of motivation (i.e. Miller & Rollnick)44 in designing the study.

Categories

Four distinct categories were identified that explained participants’ reasons for engaging in ACP: 1) Concern for Self; 2) Concern for Others; 3) Expectations About the Impact of Advance Care Planning; and 4) Anecdotes, Stories, & Experiences. (see Figure 1) No differences between the three focus groups were identified (except as noted below regarding quality-of-life).

Figure 1. What influences the person to engage in advance care planning?

Concern for Self

The richest category (in terms of both the number of themes contained and frequency) was Concern for Self, which comprised the following five themes:

-

Autonomy: Participants valued being in control of their major life decisions and this was a motivating factor for engaging in ACP. Representative statements include:“I love to drive. I don’t care where I drive, who is with me, whatever… I just love to drive. If somebody were to tell me that I could not ever again get behind the wheel and drive… I would say I don’t want [life-saving medical treatment].”“If you’re going to be able to deal with life, …be physically able to be up and about, then you want to hang in there. That thing [advance care planning] doesn’t come into effect until I become totally incapacitated and I can no longer fend for myself.”

These statements reflect the priority of being in control of daily activities, whether on a basic level (being “up and about”) or a self actualizing way (“I love to drive”). Though uniquely constituted for each person, autonomy for valued activities was a concern for self that participants universally wished to protect through ACP.

-

Meaningful Existence: The desire to maintain a meaningful existence included one’s sense of dignity and respect, as well as one’s “place” in life, spiritually and developmentally. Representative statements include:“You live your life, you live it to the best of your ability, you do good things now and you do it now today…. You should try to be happy and make the most of your health. That’s my philosophy.”“If you’re mentally incapacitated, life is almost zilch.”“I mean I’m going to do everything I can to stay healthy and stay alive and be vibrant and useful but if that’s not what God has planned for me then that’s OK too… Once a person has outlived his or her usefulness, then I think it’s time to move on.”

In describing their concerns for self, subjects focused on what makes life meaningful to them. Common threads included: being healthy, being treated with dignity and respect, making a contribution, and being a functional part of a spiritual order. Without these things, life ceased being worthwhile, and it was “time to move on.”

-

Quality-of-Life: A third theme related to the ability to enjoy everyday life.“I wouldn’t want them to keep me alive with any artificial means just to say I’m alive. I would just as soon go at that point. If there’s medical treatment available to maintain a pretty good quality-of-life then I say let’s do it, whatever it is.”Another felt quality-of-life could also determine whether to accept treatment.“In the end, even if you survive the treatment and everything, what’s it going to be after that? So my chances are 50-50 to survive this, but what is… my quality-of-life afterwards?”

For many participants, “quality-of-life” depended on having an acceptable level of health, which medical interventions could promote or undermine, depending on their degree of burden. Interestingly, this was the only instance in which the frail, underserved group differed from others —they did not mention quality-of-life and several felt that “no matter what” all life-sustaining efforts would be worthwhile.

-

The Likely Outcome: Participants also considered how prognosis, hope, and recovery influenced their wishes regarding life-sustaining medical treatment.“I would definitely want to know what my chances of survival are …, if I were in a car wreck, am I going to be a vegetable, am I going to be able to walk again, am I going to be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life?… I know they’re not always predictable, [but] I would like to know the worst and the best-case scenarios.”“I don’t want to be on a machine unless it’s going to do me some good.”“If this is temporary, I’m for it. But if I knew I was never going to come out of it, then I don’t want that.”

Participants expressed that understanding the likely outcomes of treatment was important for effective ACP. Moreover, most individuals were pragmatic: if a medical intervention was not likely to achieve specific goals, it was not worth pursuing.

-

Burden to Self & Suffering: Participants also considered psychological and physical burdens of life-prolonging medical interventions as a motivating factor for ACP.“I don’t want to be on there no two or three months or nothing like that… [J]ust let me die in peace… I don’t want the machines.”“If you’re just laying there, don’t know nobody, don’t know your kids, unconscious, don’t know nothing. And you’re on the machine… That’s terrible.”

Despite highly individual definitions of “burden,” there was a dimension of concern for self that related exclusively to how much pain and suffering the patient him/her-self would be willing to tolerate.

Concern for Others

A second category that emerged as influencing one’s decision to engage in ACP was concern for family, friends, and others who would be affected by the individual’s health problems. Three themes within this category were identified.

-

Burden to Others: Participants recognized that end-of-life care often exacted a significant emotional toll and financial burden on family, friends, and other loved ones.“I do know that it is more painful for the person trying to make these decisions… sometimes our family members go through more than we do. I do want my husband when he has to make these decisions [to be] in peace when he makes them… [D]irectives are just the beginning of that kind of thing. For real mental peace it has to be a peace-negotiating thing between human beings.”“I’d like to know, if you can know this, what position I’m putting my family in. What kind of care would be required both in terms of care and finances…”I’d be more hesitant to do something if it was going to be more of a disadvantage to my family than an advantage to myself.”“I don’t want on the machine. I don’t want my child to have to go through that.”

For some individuals, concerns about sparing suffering to loved ones, particularly their children, outweighed concerns about self. Further, many thought their family should be involved in ACP since family would be living with the consequences of choices made.

-

Input from Others. Almost all participants mentioned input from family, loved ones, and others as important influences on their motivation to engage in ACP.“I have a tendency to think more of my family members than myself and I will take that into consideration.”ACP could also be seen as a mechanism for acknowledging others’ strongly held views, as with one participant who saw ACP as a way to authorize her children’s concerns.“My kids came over to the house together and were talking about this… and the spokesman said, mama you all we got and we’ll do anything it takes to keep you alive and they agreed to it.”

- Pressure from Family. For others, however, ACP was viewed as a way to exert their independence and to actively counter the pressure they felt from others.“They [children] can’t make [end-of-life decisions] ‘cause I have my will made up.”

Expectations About the Impact of Advance Care Planning

A third category captured individuals’ perceptions about the efficacy of ACP, either to influence the end-of-life care one received, or to realize other goals such as providing helpful, unambiguous guidance to surrogates. Diversity of opinion about the likelihood that ACP would make any difference also influenced participants’ inclination to engage in ACP. Two themes were identified here.

-

Trust in the Medical System: Participants expressed varying degrees of trust in the medical system, with those who saw physicians as advocates and reliable sources of information being more likely to seek their guidance and help with ACP.“[Y]ou can’t make an informed decision about it, an advance directive, unless you have all the variables that go into making that from your doctor.”In contrast, mistrust of physicians could undermine efforts to plan care in advance:“I can’t imagine a doctor guaranteeing anything.”

These very different views about participants’ ability to rely on their doctors (for information, advice, counseling, supporting the family, etc.) affected participants’ interest in ACP, as did their general level of skepticism about the ability of ACP to overcome bureaucratic obstacles to having one’s wishes followed.

-

Predicted Effectiveness: Having information about the efficacy of medical treatments also affected perceptions of the value of ACP.“I would want to have shown me … that they’ve done their research, and they can prove to us that this drug… [can] make your life better.”“Choices have to be made but choices can’t be made unless you’re given guidelines and percentages and options that include everything.”

These statements point to the value people place on having an accurate understanding of the medical facts for engaging in ACP.

Anecdotes, Stories, and Experiences

The fourth and final category that emerged describes the influence that anecdotes, stories, and experiences have on people’s willingness to engage in ACP. Three themes emerged within this category.

-

Current Events: Stories in the media prompted participants to consider ACP and its relevance to their own situations. For instance, the following statements referred to the turmoil facing Terri Schiavo at the time.“Like this case now down south, this lady has been on it for years. Her husband, they know there’s no hope, so is there a time limit that you can set? Let’s say that after three months or after six months to pull the plug?”“[T]he politicians shouldn’t be involved in that. It should have been done between the husband and wife a long time ago.”

Such current news events prompted many people to consider taking action to prevent similar tragedies from befalling them.

-

Emotional Response to Caregiving: Many participants had taken care of someone at the end of life, or heard stories from others who had struggled through the difficulty of physically and/or emotionally supporting someone who was fragile and dying:“We had to take major action with the head of the family because he was not one to take charge… We were so angry [that he] would let [my mother] go downhill just [so she could still] take care of him.”“This emotional thing that’s involved here is unbelievable.”

Participants’ detailed and often emotional stories about caregiving were compelling, typically described as negative, and left strong impressions. Many participants relayed that such experiences caused them to think about what they would want for themselves, and as such may have been the strongest motivator for engaging in ACP.

-

Past Experiences Making Decisions for Others: Witnessing the suffering of others and helping make decisions for them also left strong and lasting impressions.“I had a friend that I had to make a decision about … whether to take him off of life support… They said he could never get any better and he would always have to be on life support. So then we had to decide whether to take him off or not… Then all the kids had to come… That is a hard decision to make.”“my mother-in-law hung on and hung on the longest time. My husband (her son) kept saying, mom don’t give up, keep trying. She had to literally call on the telephone… She called from the hospital bed and asked if she could let go. She said I can’t hang on anymore and he said, OK mom if you have to, it’s OK. It was shortly after that that we lost her.”

Participating in end-of-life decisions for another person affects one’s perspective by moving ACP from a theoretical concern to a practical undertaking.

Discussion

This study identifies thought processes, values, and contextual factors that influence individuals to engage in advance care planning. The discussion that follows will focus on how healthcare providers might operationalize our findings in their efforts to promote advance care planning.

Not surprisingly, Concern for Self emerged as the strongest influence for engaging in ACP. This suggests that by helping individuals see a connection with their own interests healthcare providers can motivate them to invest time and energy in the complex and sometimes challenging self-reflective process that is ACP. As such, healthcare providers can show patients how, as a process for clarifying and communicating what is important to them and why, ACP can help 1) articulate individuals’ near and long-term goals; 2) express any relationships between their spiritual views and specific courses of action; and 3) promote individuals’ being treated with dignity and respect.

Because individuals recognize that end-of-life decisions often have the greatest impact on others, it’s important to help patients appreciate that reflecting on and communicating their wishes can alleviate burden to family and friends.7, 45 Our findings suggest that healthcare providers can reinforce this insight by drawing on individuals’ own experiences and observations regarding end-of-life experiences. For these not only contribute to knowledge, but also elicit strong emotional responses that can influence people’s views about ACP.

We also found that the perceived benefit of ACP was related to participants’ views about its expected efficacy. This suggests that to the extent that we as healthcare providers can increase a person’s trust in physicians and/or the medical system, we can promote ACP.16 For despite the many factors that influence whether a patient’s expressed wishes will prevail,6 whether ACP is considered worth engaging in depends greatly on whether an individual thinks it will likely influence end-of-life medical decision-making.

Limitations

Because this was a small, non-random sample of middle-aged or older, English speaking residents of central Pennsylvania, generalizability may be limited.16, 46, 47 Such restricted participation is a natural consequence of focus group research, which is not designed to generate statistically significant generalizable findings. However our sample included >30% African-Americans; our methodology allowed for open-ended, in-depth interviews to explore and clarify participants’ concerns, motivations, and underlying values;48, 49 and the themes and categories identified are readily generalizable to other populations.

A second limitation common in interview-based research is social desirability bias, with participants presenting themselves so as to be viewed favorably by others. To minimize this, the facilitator did not indicate approval or disapproval of input, there were no “correct” answers, and group discussions were designed with a free-flowing format that allowed for in-depth exploration of people’s values and their origins.

A third possible limitation is that context —i.e., the realities of confronting these issues—may overdetermine individuals’ willingness to engage in ACP.30, 31 The themes identified, however, are not age- or condition-dependent, and include factors readily applicable to diverse populations.

Conclusion

Though advance care planning is viewed positively by patients and healthcare providers,50 relatively little is known about how people understand ACP and/or what motivates them to undertake this process. Our results identify key influences and provide a framework that healthcare providers can use to more effectively engage patients in dialogue and encourage ACP.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from NIH/NINR (R21 NR 008539-01).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare with regard to this research.

Contributor Information

Benjamin H. Levi, Departments of Humanities and Pediatrics at Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey, PA. bhlevi@psu.edu.

Cheryl Dellasega, Department of Humanities at Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey, PA.

Megan Whitehead, Department of Humanities at Penn State College of Medicine in Hershey, PA.

Michael J. Green, Departments of Humanities and Medicine at Penn State College of Medicine.

References

- 1.Doukas DJ, McCullough LB. The values history. The evaluation of the patient’s values and advance directives. J Fam Pract. 1991 Feb;32(2):145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo B, Steinbrook R. Resuscitating advance directives. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Jul 26;164(14):1501–1506. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles SH, Koepp R, Weber EP. Advance end-of-life treatment planning. A research review. Arch Intern Med. 1996 May 27;156(10):1062–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prendergast TJ. Advance care planning: pitfalls, progress, promise. Crit Care Med. 2001 Feb;29(2 Suppl):N34–39. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz CE, Wheeler HB, Hammes B, et al. Early intervention in planning end-oflife care with ambulatory geriatric patients: results of a pilot trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Jul 22;162(14):1611–1618. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins HS. Controlling death: the false promise of advance directives. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jul 3;147(1):51–57. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, Thiel EC, Kelner M, Mendelssohn DC. Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Apr 27;158(8):879–884. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.8.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAuley WJ, Buchanan RJ, Travis SS, Wang S, Kim M. Recent trends in advance directives at nursing home admission and one year after admission. Gerontologist. 2006 Jun;46(3):377–381. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelter KL, Elliott BA, Bruno CA. Living will completion in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 1992 May;152(5):954–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, Collier AC. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Jun 12;160(11):1690–1696. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Despreaux MC, DT, Drickamer MA. Discussing Advance Directives: A Study of Outpatients’ Attitudes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996 Apr;11(1):114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forow L. The Green Eggs and Ham Phenomenon. Hastings Center Report. 1994 Nov-Dec;24(6):S29–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holley JL, Hines SC, Glover JJ, Babrow AS, Badzek LA, Moss AH. Failure of Advance Care Planning to Elicit Patients’ Preferences for Withdrawal from Dialysis. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 1999 Apr;33(4):688–693. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchand L, Fowler KJ, Kokanovic O. Building successful coalitions to promote advance care planning. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2005 Nov-Dec;22(6):437–441. doi: 10.1177/104990910502200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchand L, Fowler KJ, Kokanovic O. Building successful coalitions for promoting advance care planning. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006 Mar-Apr;23(2):119–126. doi: 10.1177/104990910602300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins HS, Geppert CM, Gonzales A, Cortez JD, Hazuda HP. Cross-cultural similarities and differences in attitudes about advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2002 Jan;17(1):48–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SUPPORT PI. A Controlled Trial to Improve Care for Seriously Ill Hospitalized Patients: The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995 Nov 22/29;274(20):1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teno JM, Lynn J, Phillips RS, et al. Do formal advance directives affect resuscitation decisions and the use of resources for seriously ill patients? SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Clin Ethics. 1994 Spring;5(1):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upadya A, Muralidharan V, Thorevska N, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Patient, physician, and family member understanding of living wills. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Dec 1;166(11):1430–1435. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-503OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volandes AE, Lehmann LS, Cook EF, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, Gillick MR. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Apr 23;167(8):828–833. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD, et al. Advance directives as acts of communication: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Feb 12;161(3):421–430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004 Mar-Apr;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL. Death and end-of-life planning in one midwestern community. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Feb 23;158(4):383–390. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teno J, Lynn J, Phillips R, et al. Do advance directives save resources? Clin Res. 1993 Apr;41(2):551A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teno JM, Licks S, Lynn J, et al. Do advance directives provide instructions that direct care? SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Apr;45(4):508–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. Jama. 2005 Jul 20;294(3):359–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson DG, Tobin DR. End-of-life conversations: evolving practice and theory. Jama. 2000 Sep 27;284(12):1573–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora NK, McHorney CA. Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care. 2000 Mar;38(3):335–341. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry SR, Singer PA. The cancer specific advance directive. Cancer. 1998 Apr 15;82(8):1570–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ditto PH, Jacobson JA, Smucker WD, Danks JH, Fagerlin A. Context changes choices: a prospective study of the effects of hospitalization on life-sustaining treatment preferences. Med Decis Making. 2006 Jul-Aug;26(4):313–322. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried TR, Bradley EH. What matters to seriously ill older persons making end-of-life treatment decisions?: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2003 Apr;6(2):237–244. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR. Assessment of patient preferences: integrating treatments and outcomes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002 Nov;57(6):S348–354. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002 Apr 4;346(14):1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Apr 24;166(8):890–895. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer PA. Disease-specific advance directives. Lancet. 1994 Aug 27;344(8922):594–596. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr D, Khodyakov D. End-of-life health care planning among young-old adults: An assessment of psychosocial influences. Journals of Gerontology Series B-psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007 Mar;62(2):S135–S141. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Annas GJ. “Culture of life” politics at the bedside —the case of Terri Schiavo. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 21;352(16):1710–1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMlim050643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quill TE. Terri Schiavo--a tragedy compounded. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 21;352(16):1630–1633. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfson J. Erring on the side of Theresa Schiavo: reflections of the special guardian ad litem. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005 May-Jun;35(3):16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon NP, Shade SB. Advance directives are more likely among seniors asked about end-of-life care preferences. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Apr 12 7;159:701–704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green MJ, Levi BH. Development of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. Health Expectations. 2009;12(1):60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan DL. Focus Groups. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreuger RA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. London: Sage Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller WJ, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist. 2005 Feb;45(1):107–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caralis PV, Davis B, Wright K, Marcial E. The influence of ethnicity and race on attitudes toward advance directives, life-prolonging treatments, and euthanasia. J Clin Ethics. 1993 Summer;4(2):155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996 Nov;11(11):651–656. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basch CE. Focus group interview: an underutilized research technique for improving theory and practice in health education. Health Educ Q. 1987 Winter;14(4):411–448. doi: 10.1177/109019818701400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dilorio C, Hockenberry-Eaton M, Maibach E, Rivero T. Focus groups: an interview method for nursing research. J Neurosci Nurs. 1994 Jun;26(3):175–180. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001 Sep;22(3):727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]