Abstract

In the secondary lymphoid organs, intimate contact with follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) is required for B cell retention and antigen-driven selection during the germinal center response. However, selection of self-reactive B cells by antigen on FDCs has not been addressed. To this end, we generated a mouse model to conditionally express a membrane-bound self-antigen on FDCs, and monitor the fate of developing self-reactive B cells. Here, we show that self-antigen displayed on FDCs mediates effective elimination of self-reactive B cells at the transitional stage. Notwithstanding, some self-reactive B cells persist beyond this checkpoint, showing evidence of antigen experience and intact proximal BCR signaling, but they are short-lived and unable to elicit T cell help. These results implicate FDCs as an important component of peripheral B cell tolerance that prevent the emergence of naïve B cells capable of responding to sequestered self-antigens.

Introduction

Generating a diverse repertoire of B cells reactive against foreign antigens, yet tolerant to self-constituents, is imperative for an effective immune system. Random gene rearrangement at the immunoglobulin loci results in the majority of newly formed B cells being self-reactive (1). Studies employing immunoglobulin transgenic mice have established that newly formed bone marrow B cells expressing self-reactive BCRs are rendered innocuous by mechanisms including apoptosis, induction of anergy, or receptor editing (2).

In the case of peripheral B cell tolerance, models have primarily focused on B cell autoreactivity against tissue-specific antigens. An early study using a thyroid-specific self-antigen-expressing mouse model failed to reveal any selection mechanisms against autoreactive B cells, which was attributed to a lack of access to self-antigen (3). On the other hand, B cell elimination or arrest at the transitional stage was evident in liver-specific self-antigen mouse models (4, 5). In a polyclonal repertoire, the existence of peripheral tolerance mechanisms is supported by the striking observation that the frequency of self-reactive B cells drops decidedly following egress from the bone marrow and prior to entry into the pool of naive mature recirculating B cells (1). Indeed, studies have shown that rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients have a defect at this second critical checkpoint (6, 7).

The above findings suggest that a large proportion of self-reactive B cells are eliminated as transitional B cells progressing towards full maturity and immunocompetence in the spleen. Transitional B cells are sub-divided into the transitional 1 (T1) and the more mature transitional 2 (T2) subsets (8-11). An additional splenic B cell subset that was originally designated T3 cells and bears a surface marker phenotype similar to T1 and T2 cells has since been recognized as containing the short-lived anergic “An1” B cell subset (12). Histological evidence suggests that T1 B cells reside in the red pulp while T2 B cells enter the follicle (9, 10). Similar to immature B cells in the bone marrow, T1 B cells are prone to apoptosis, particularly in response to BCR engagement. T2 B cells are less sensitive to apoptosis and are able to survive and proliferate in response to antigen if provided with T cell help in the form of IL-4 or CD40 stimulation; however, T2 B cells are inefficient at eliciting these responses due to their incapacity to upregulate T cell costimulatory molecules (13). Little is known regarding the microenvironmental cues that promote the maturation or, in the case of self-antigen recognition, elimination of transitional B cells.

In the secondary lymphoid organs, >90% of B cells are in intimate contact with the vast network of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) (14). FDCs present antigen to B cells in the form of immune complexes and opsonized foreign antigens by Fc and complement receptors, respectively. These interactions are important for B cell selection and contribute to affinity maturation during the germinal center response (15). Indeed, recent studies have shown that inducible ablation of FDCs results in dissolution of germinal centers (16). Selection of self-reactive B cells by antigens displayed on FDCs has not been addressed despite the fact that complement components can also bind self-constituents, and germinal center and memory B cells are noted to express self-reactive IgG that can serve as a source of immune-complexed self-antigen (17, 18). To address whether FDCs displaying self-antigen can select self-reactive B cells in a definitive and physiologic setting, we generated a mouse model to conditionally express self-antigen on FDCs. Two contrasting outcomes could be envisaged; (1) the immunogenic properties of FDCs and synapse formation with antigen-specific B cells may promote the activation and survival of self-reactive B cells, or (2) the tolerogenic program of newly formed B cells may confer susceptibility to apoptosis upon BCR engagement. Our results support the latter theory, showing that FDCs mediate effective elimination of self-reactive B cells at the transitional stage. Thus, ours is the first report of self-reactive transitional B cell elimination by encounter with FDC-displayed antigens in the spleen, a location where B cells naturally progress from transitional to mature cells.

Materials and Methods

mDELloxp mouse generation

The DEL construct was synthesized according to the published amino acid sequence with one modification at Y3F, which eliminates an epitope for I-Ab-restricted T cells (19, 20). Synthesized DEL was fused to the MHC I transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail cDNA sequence region isolated from a C57BL/6 mouse and cloned into the LB2-FLIP lentiviral vector (21) (Hynes Laboratory) (Figure 1A). High titer lentivirus (5.7×109 viral particles/mL) was injected into C57BL/6 embryos as described (22). Germline transmission of the transgene was confirmed by PCR of the mDEL transgene and expression of surface marker Thy1.1 by flow cytometry. The following primers were used to indicate the presence of the transgene: Forward Primer – TGA GAT CAG ACA TAA CAG AGG CCG and Reverse Primer – GCT AGA GAA TGA GGG TCA TGA ACC (94°C, 3’, (1 time); 94°C, 30s, 53.8°C, 30s, 72°C, 45s, (35 times); 72°C, 7’, (1 time)). Direct immunodetection of mDEL was unachievable due to the lack of appropriate staining reagents. However, lymphoid tissue-specific Cre activity was confirmed by the loss of Thy1.1 expression (Figure S1A, B upper panel) and presence of recombined mDEL product by PCR in blood samples obtained from Cd21cremDELloxp mice but not from control mice and mDELloxp mice (Figure S1B lower panel). Moreover, only HEL-binding B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp lymphoid tissues down-modulated surface Ig expression and upregulated activation markers in response to endogenous antigen (Figure S1C-E).

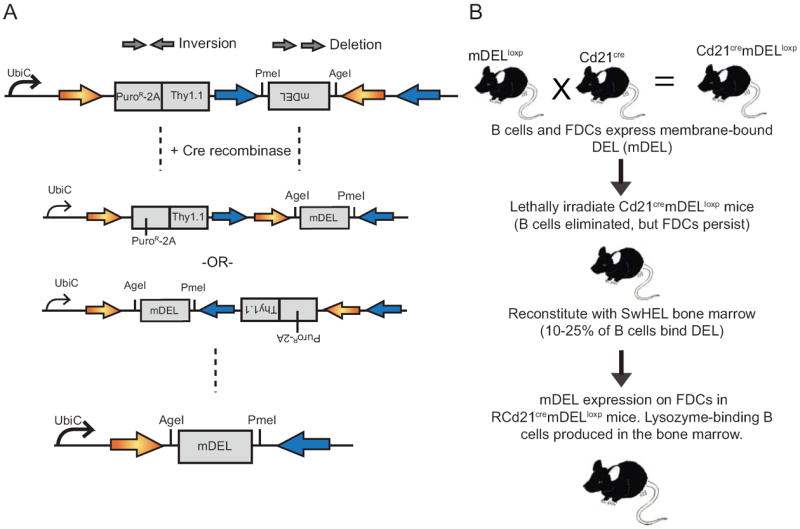

Figure 1. A mouse model to conditionally express membrane-bound Duck Egg Lysozyme on FDCs, and monitor the fate of arising mDEL-specific B cells.

A, Schematics of the LB2-FLIP lentiviral vector used for mDELloxp mouse generation. Membrane-bound DEL (mDEL) was cloned into the LB2-FLIP lentiviral vector (21). Two distinct sets of loxP sequences (orange and blue arrows) flank the inverted mDEL sequence. Integration allows for ubiquitous expression of Puromycin and the Thy1.1 surface marker, while the inverted mDEL sequence prevents transcription. Cre-recombinase mediates inversion events of both sets of loxP recombination sequence sets leading to mDEL transcription. Subsequent recombination events lead to deletion of Thy1.1 as the final recombination event and the retention of heterologous loxP sites that cannot recombine. B, Cd21cremDELloxp mice were generated by intercrossing mDELloxp mice and Cd21cre mice to express mDEL on FDCs (and mature B cells). Cd21cremDELloxp and control mice were subsequently lethally irradiated and reconstituted with BM from SWHEL mice (denoted by R Cd21cremDELloxp) unless otherwise noted.

Mice

mDELloxp mice were bred to Cd21cre mice (23) to generate Cd21cremDELloxp mice. Cd21cremDELloxp or control mice were lethally irradiated (10 gray) and reconstituted with bone marrow from SWHEL mice (RCd21cremDELloxp) (24) or MD4 mice (where indicated) (25) by intravenous injection six hours post-irradiation and analyzed 7-12 weeks later. Some mice were reconstituted with lineage-depleted bone marrow isolated by negative MACS sorting of cells labeled with biotinylated anti-B220, -CD19, -IgM, -CD3, and -CD11b (eBioscience) antibodies followed by anti-biotin MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). For BAFF studies, SWHEL mice were crossed to BAFF transgenic mice (26) (SWHELBAFFTg) and lineage-depleted bone marrow from the progeny was used to reconstitute Cd21cremDELloxp (Cd21cremDELloxSWHELBAFFTg) or control (control-SWHELBAFFTg) mice. For transient BAFF studies, Cd21cremDELloxp or control mice were reconstituted with SWHEL bone marrow. Eight weeks after reconstitution, RCd21cremDELloxp or control mice received daily i.p. injections of soluble human BAFF (7 μg/day) (eBioscience) for 6 days and were sacrificed for analysis 7 days after initial BAFF injection. Cd21cremDELloxp, SWHEL, SWHELBAFFTg, ML5 (25), MD4, and OTII mice (gift from Linda Bradley, SBMRI) were housed in pathogen-free environment in the Animal Facility at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute and were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. All experiments conformed to the ethical principles and guidelines approved by the SBMRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from spleen, lymph node, and bone marrow were incubated with either biotinylated HEL (Genetex) or with soluble HEL followed by biotinylated anti-HEL antibody (Rockland). The following antibodies were used from eBioscience unless otherwise noted: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), -CD3 (145-2C11), -Thy1.1 (HIS51), -CD21/35 (8D9), -CD23 (B3B4), -IgM (II/41), -CD93 (AA4.1), -IgD (11-26), -CD24 (M1/69), -CD86 (PO3.1), -CD69 (H1.2F3), -MHCII (M5/114.15.2), -CD138 (281-2, BD Pharmingen), -GL7 (BD Pharmingen), -FAS (BD Pharmingen), -IgG1 (A85-1, BD Pharmingen), -BAFFR (H22-E16), and Streptavidin-PerCP-Cy5.5 and -Pecy7. Live cells were assessed by forward and side scatter profiles. For intracellular Bim stain, splenocytes were incubated with surface antibodies and fixed in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD biosciences) for 15 minutes on ice, washed two times, and incubated overnight with Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience). Splenocytes were subsequently incubated with anti-Bim rabbit mAb (C34C5, Cell Signaling) or isotype control (rabbit DA1E mAb IgG, Cell Signaling Technology) followed by secondary FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For intracellular pAKT staining, two million splenic cells were incubated at 37°C and stimulated with anti-IgM F(ab’)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at a concentration of (10 μg/mL) for the indicated time point. Stimulations were halted by adding 37°C BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer for 10 minutes and washing two times with Permeabilization Buffer. Cells were subsequently incubated with surface antibodies in FACS buffer, washed, and incubated in 0.2% saponin buffer with phospho-AKT antibody (Ser473, D9E, Cell Signaling) for 1 hour and secondary anti-rabbit FITC antibody for 1 hour. For the detection of DNA strand breaks, splenic B cells were isolated and labeled with fluorescein-dUTP (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All cells were acquired on a FACSCanto using FACS DIVA software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar). Data are displayed with logarithmic scale.

In vitro culture

B cells were isolated from splenic cells according to standard procedures and were cultured in a 96- or 48- well plate at 1.5 × 106 B cells/mL in complete RPMI media with or without soluble HEL or DEL (500 ng/mL) for sixteen hours.

T cell-B cell collaboration

T cells were isolated from OTII spleens by negative MACs sorting of cells labeled with biotinylated anti-B220, -CD11b, and -CD11c (eBioscience) antibody followed by anti-biotin MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). B cells were isolated from Cd21cremDELloxp or control spleen by negative MACs sorting of cells labeled with anti-CD43 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). T and B cells were labeled with 2.5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes) according to manufacturer’s instructions and co-cultured at 1.75 × 106 cells/mL (1 × 106 B cells/mL and 0.75 × 106 T cells/mL) in the presence of OVA peptide 323-239 (500 ng/mL), OVA (1 μg/mL), or HEL-OVA (2 μg/mL) for 3 days.

Calcium flux

Two million splenic B cells were isolated and resuspended in media with Fluo-4 at 10 uM (Molecular Probes). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30-45 minutes in the dark, washed with media, and labeled with B220-PE for 20 minutes. Stimulations to induce calcium release were done with either anti-IgM F(ab)’2 or with HEL-APC fusion protein generated by combining biotinylated HEL with streptavidin-conjugated APC at a 5:1 ratio by weight for five minutes.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Splenic tissue was embedded in Tissue-TEK O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek U.S.A., Torrance, CA) and frozen at -80°C. Frozen tissue were then sectioned, mounted on Superfrost/Plus microscope slides, fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes, and blocked with 5% FBS and 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. Sections were first incubated with soluble HEL for 30 minutes. Tissues were then stained with the following antibodies: biotinylated anti-HEL (Rockland), Streptavidin Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), CD5 (53-7.3), and IgD (11-26). Histology sections were imaged with a Zeiss Axio ImagerM1 using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed by using unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s T-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Reduced self-reactive B cells in mice expressing mDEL on FDCs

To study the effect of FDC-bound self-antigen on late-stage development of self-reactive B cells, we generated a transgenic mouse line, mDELloxp, that conditionally expresses the ‘self’ protein duck egg lysozyme (DEL) in membrane-bound form (mDEL) after Cre-mediated recombination (Figure 1A). The mDELloxp mice were bred to Cd21cre mice (Cd21cremDELloxp), which express Cre recombinase in mature B cells and FDCs (23, 27). To eliminate CD21Cre-expressing B cells, but preserve mDEL expression on radioresistant FDCs, Cd21cremDELloxp and control mice (littermates carrying either the Cd21cre or mDELloxp transgene) were lethally irradiated (10 gray) and reconstituted with bone marrow from SWHEL mice, denoted RCd21cremDELloxp, in which 10-20% of B cells express a high affinity (4.5 × 1010 M−1) B cell receptor (BCR) specific for hen egg lysozyme (HEL) that also binds DEL with moderate affinity (1.3 × 107 M−1) (19, 24) (Figure 1B).

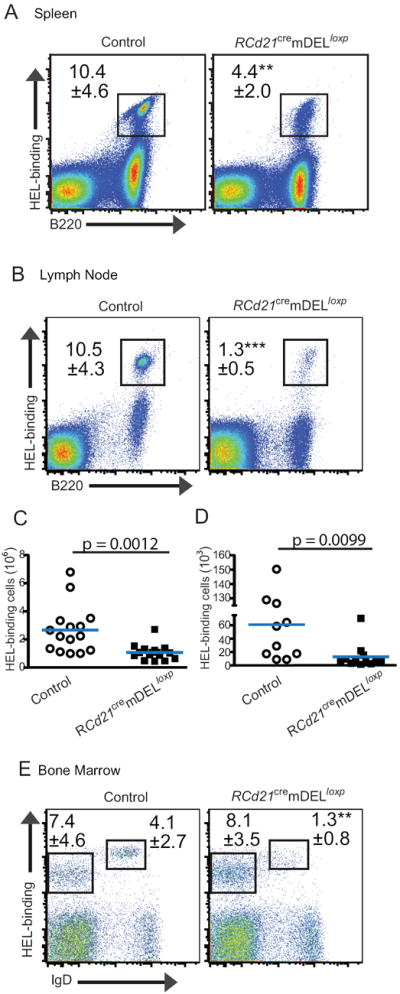

Analysis of RCd21cremDELloxp mice (reconstituted with SWHEL bone marrow) showed a significantly decreased frequency of HEL-binding B cells in both the spleen (Figure 2A) and lymph node (Figure 2B), which corresponded to a greater than two-fold reduction in the absolute number of HEL-binding cells in the spleen (Figure 2C) and a five-fold reduction in the lymph node (Figure 2D). Similarly, Cd21cremDELloxp mice reconstituted with bone marrow from conventional anti-HEL Ig transgenic (MD4) mice in which 90% of B cells bind to HEL (25) also showed a greater than two-fold reduction in the frequency of HEL-binding cells in the spleen (Figure S2A) and a nearly three-fold reduction in the lymph nodes (Figure S2B). Consistent with the fact that mature FDCs are only present in the peripheral lymphoid tissues, the percentages of immature (IgD-) HEL-binding B cells in the bone marrow of RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice were similar (Figure 2E). By comparison, mature (IgD+) recirculating HEL-binding B cells in the bone marrow were decreased in RCd21cremDELloxp mice compared to controls (Figure 2E), reflecting the reduced percentage of mature B cells exiting the spleen and entering circulation. The results of these analyses of primary and secondary lymphoid organs indicate that mDEL self-antigen expression on FDCs results in the loss of HEL-binding B cells.

Figure 2. Reduced HEL-binding B cells in mice expressing mDEL.

Flow cytometry plots of HEL-binding B cells in the spleen (A) and LN (B). Cell counts of total HEL-binding B cells in the spleen (C) and LN (D). Flow cytometry plots of BM show the frequency of immature (IgD-) and mature (IgD+) HEL-binding B cells (E). Representative plots are shown. Frequencies (B220+ gated) and SD values from four independent experiments (n=3-5 per experimental group, error bars are SD, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005) are shown.

Self-reactive B cells are eliminated at the transitional stage

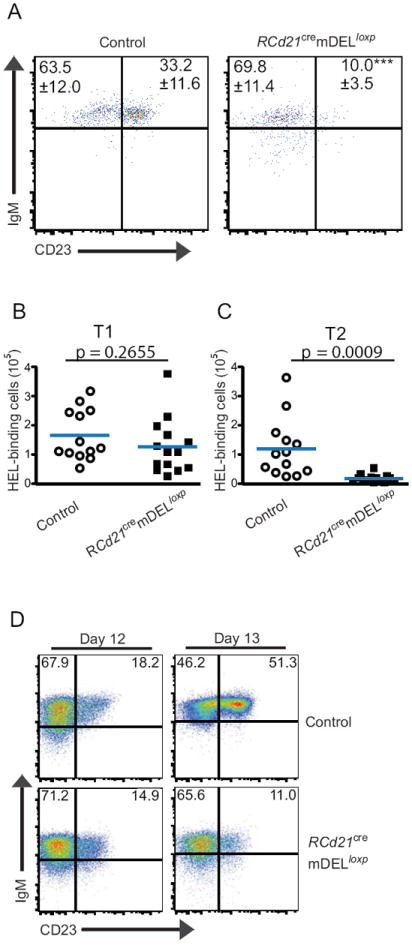

The unaltered frequency of immature HEL-binding B cells in the bone marrow, but reduced frequency of mature HEL-binding B cells in the bone marrow and spleen in RCd21cremDELloxp recipient mice led us to examine the transitional B cell compartment in the spleen (13). Using common surface markers to delineate T1, T2, and mature follicular (FO) B cell sub-populations (8, 10), no significant differences in the percentage (Figure 3A) or absolute number (Figure 3B) of HEL-binding T1 B cells (AA4.1+, IgM+, CD23-, CD21low CD24hi) were noted between RCd21cremDELloxp and control recipients. In striking contrast, a more than 3-fold decrease in the frequency and a nearly seven-fold decrease in the absolute number of HEL-binding T2 B cells (AA4.1+, IgM+, CD23+, CD21+, CD24hi) were observed in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients (Figure 3A, C and Figure S3A). In contrast, non HEL-binding T2 B cells remain present in RCd21cremDELloxp mice (Figure S3B). A population of CD21low B cells that are CD21low and expresses lower levels of HSA was observed in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients (Figure S3A) and may represent a population of immature B cells that have encountered self-antigen. These results suggest that HEL-specific B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients are either unable to complete maturation to the T2 stage, or that they reach the T2 stage but are quickly eliminated after encountering self-antigen.

Figure 3. HEL-binding B cells are eliminated at the T1→T2 transition and do not collaborate with cognate T cells.

Analysis of splenic B cell subsets by flow cytometry in adult (A-C) and newly reconstituted mice (D). A Flow cytometry plots of RCd21cremDELloxp and control spleens show the frequency of T1 (IgM+CD23-) and T2 (IgM+CD23+) B cells (HEL-binding, AA4.1+ gated). T1 (B) and T2 (C) HEL-binding B cell subsets from RCd21cremDELloxp and control spleens were enumerated. Frequencies and cell counts with SD values from three independent experiments (n=3-5 per experimental group, error bars are SD, ***P < 0.0005) are shown. D, Spleens from RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice were analyzed on days 12-13 after BM reconstitution. Flow cytometric analysis showing T1 (IgM+CD23-) and T2 (IgM+CD23+) B cell frequency (HEL-binding, AA4.1+ gated). Representative plots are shown from two independent experiments (n=2-3 per experimental group).

To further investigate B cell maturation and selection at the T1→T2 stage, spleens from RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice were analyzed at early time points after bone marrow reconstitution when the majority of peripheral B cells are at the transitional stage (28). Twelve days after reconstitution with SWHEL bone marrow, similar frequencies of HEL-binding T1 cells were observed in both control and RCd21cremDELloxp mice (Figure 3D, left panels), and only a slight reduction of HEL-binding T2 B cells was observed in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients relative to controls (Figure 3D, left panels). By day 13, approximately half of the HEL binding B cells were of the T2 phenotype in control mice, indicating progression from the T1 to the T2 stage. The, the frequency of non-HEL-binding T2 B cells was similar in RCd21cremDELloxp and control recipients (data not shown). However, the frequency of HEL-binding T2 cells was sharply reduced in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients (Figure 3D, right panels). Given that we observe comparable populations of T2 cells in RCd21cremDELloxp and control recipients at day 12, but a selective loss of these cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice at day 13, these observations are most consistent with elimination of self-reactive B cells by FDCs at the T1→T2 transition, although we cannot formally exclude the contribution of an arrest in maturation at the T1 stage.

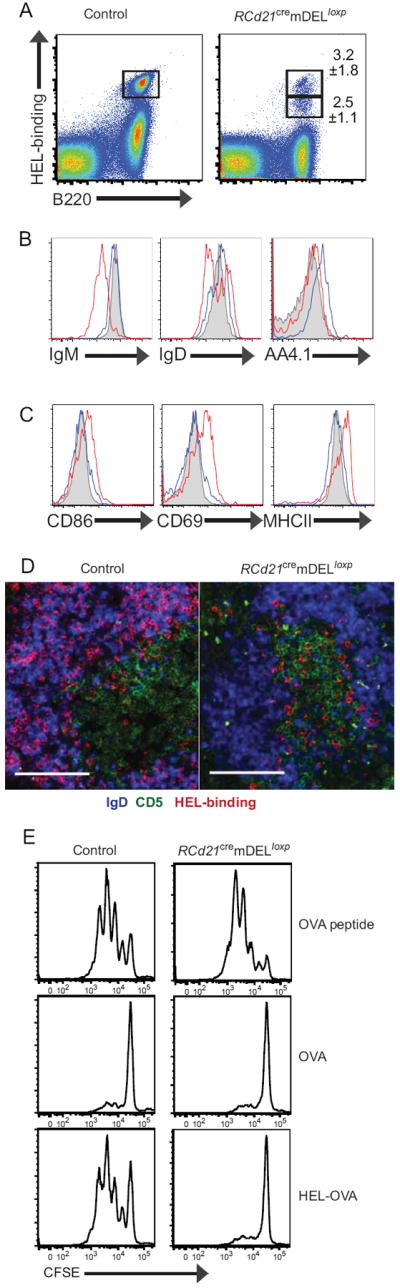

Partial activation of a subset of self-reactive B cells in mice expressing mDEL

Despite the dramatic loss of self-reactive B cells at the transitional stage, flow cytometric analysis also revealed the presence of a low-HEL-binding sub-population of B cells that was present in the spleen, but not in the lymph node or peripheral blood, of RCd21cremDELloxp recipients and was not present in control mice (Figure 4A, B, Figure S1D, E). This phenotype reflected decreases in both surface IgM and IgD, suggesting that these cells had encountered antigen (Figure 4B) (29). The reduced frequency of T2 and follicular HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice suggests that the high-HEL-binding population represents transitional B cells that have yet to encounter FDCs displaying mDEL. As predicted, the majority of high-HEL-binding B cells displayed high CD93 levels (assessed by the AA4.1 antibody), consistent with the phenotype of transitional B cells (Figure 4B, right histogram). The low-HEL-binding population consisted mostly of AA4.1low B cells (Figure 4B, right histogram) and may represent B cells that have matured before encountering DEL self-antigen, or are antigen-experienced late-stage transitional B cells that require multiple antigenic ‘hits’ before elimination, as previously suggested (30).

Figure 4. Partially activated phenotype of HEL-binding B cells in mice expressing mDEL.

Analysis of the HEL-binding B cell subsets found in RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice by flow cytometry (A-C) and histology (D). A, Flow cytometry plots showing gates (B220+ gated) on the high and low HEL-binding B cell population from RCd21cremDELloxp and control spleens. B, Overlaid histograms of IgM, IgD and AA4.1 expression levels of control (gray filled histogram) and high- (blue) and low- (red) HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp B cells. C, Overlaid histograms of CD86, CD69, and MHCII expression levels of control (gray filled histogram) and high- (blue) and low- (red) HEL binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp B cells. D, T cells (CD5+, green), B cells (IgD+, blue), and HEL-binding cells (red) in splenic sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. Representative plots (A-C) and images (D) are shown from three independent experiments (n=3-5 per experimental group, mean frequencies ± SD values are shown). E, B-T collaboration. B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp or control mice and T cells from OTII mice were isolated, CFSE-labeled, and cultured together in the indicated conditions. Three days after culture, CFSE levels of CD4+ cells were assessed by flow cytometry. Representative plots from two independent experiments (n=2 per experimental group).

Assessment of various B cell activation markers indicative of antigen experience revealed that low-HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice expressed elevated CD86, CD69, and MHCII levels relative to the high-HEL-binding cells in RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice (Figure 4C, Figure S2C). This sub-population of activated B cells was not present in non-lymphoid tissues (Figure S1C) and could not be induced with serum from Cd21cremDELloxp or control mice (Figure S1F), consistent with FDC-restricted expression of mDEL in membrane form. Although the low-HEL-binding B cells expressed higher levels of activation markers, immunohistological staining did not reveal germinal centers and flow cytometric analysis confirmed that the low-HEL-binding B cells were not germinal center B cells (data not shown). Splenic sections from RCd21cremDELloxp mice also showed that the majority of HEL-binding B cells were at the T-B border, a location consistent with the documented movement of antigen-activated B cells seeking T cell contact (31) (Figure 4D). The population of B cells with low-HEL-binding capacity and elevated activation marker expression was restricted to the spleen (data not shown), suggesting that the HEL-binding B cells that encounter self-antigen bound to FDCs do not egress from the secondary lymphoid organs but are eliminated at the site of antigen encounter.

HEL-specific B cells from mDEL-expressing mice are unable to induce T cell proliferation

Given the location and the activated phenotype of the HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice, we sought to determine if these B cells could successfully stimulate antigen-specific T cells to undergo clonal expansion. Splenic B cells from either control or RCd21cremDELloxp mice were isolated and cultured with OVA-binding CD4+ T cells isolated from OTII mice in the presence of OVA peptide, OVA protein, or HEL-OVA-conjugated protein. Using CFSE dilution as a measurement of cell division, we found that B cells from both control and RCd21cremDELloxp mice induced T cells to undergo several rounds of cell division during three days of culture with OVA-peptide (Figure 4E, left panels). As expected, T cells did not proliferate in the presence of intact OVA protein (Figure 4E, middle panels). Strikingly, HEL-specific B cells from control mice but not from RCd21cremDELloxp mice induced T cell proliferation in the presence of HEL-OVA protein (Figure 4E, right panels). Although HEL-binding B cells migrated to the T-B border (Figure 4D), these results indicate that HEL-specific B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp mice are unable to act as effective antigen presenting cells (APCs) to collaborate successfully with T cells.

Self-reactive B cells have intact proximal BCR signaling, but are prone to apoptosis in mice expressing mDEL

Although a population of antigen-experienced HEL-binding B cells is present in RCd21cremDELloxp spleens, it was important to determine if BCR signaling remained intact (as measured by induced Akt phosphorylation (pAKT) and calcium flux). Both non-HEL- and HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice showed increased amounts of pAKT after stimulation with anti-IgM F(ab)’2 (Figure 5A). Gating on the low and high Cd21cremDELloxp HEL-binding populations showed similarly increased pAKT levels (data not shown). Analysis of intracellular calcium levels by flow cytometry also revealed a similar degree of calcium release between control and RCd21cremDELloxp HEL-binding B cells (Figure 5B). Together, these findings indicate that the PI3K- and PLCγ2-dependent pathways and upstream tyrosine kinase activity induced by BCR engagement remain intact in HEL-binding self-reactive B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp recipients.

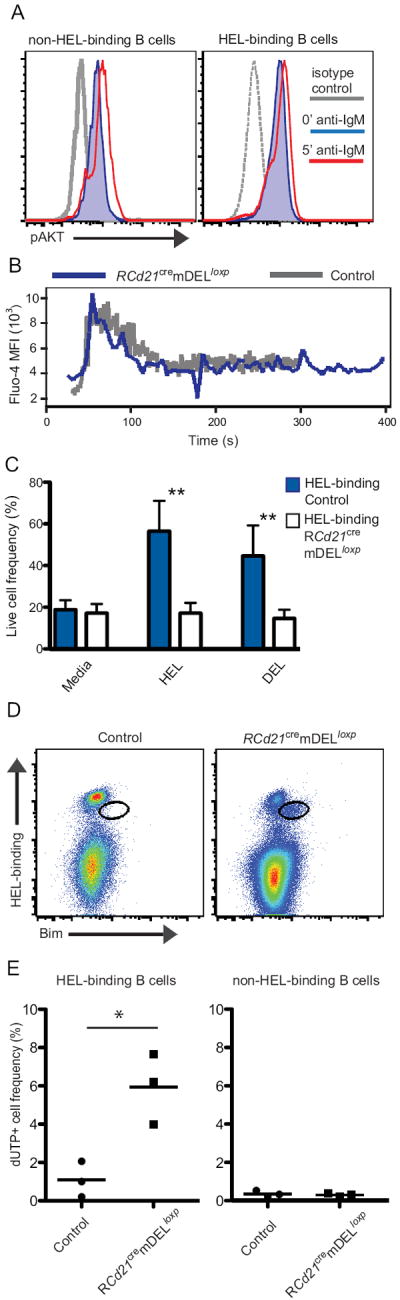

Figure 5. Intact proximal BCR signaling, but high Bim expression in low HEL-binding B cells.

A, Overlaid histograms of intracellular pAKT levels of unstimulated (blue, shaded) and IgM F(ab)’2 stimulated (red) B cells and isotype control (gray) from RCd21cremDELloxp non- and HEL-binding cells of the spleen. A representative plot is shown from two independent experiments (n=2-4 per experimental group). B, Calcium mobilization assay. B cells were stimulated with HEL-APC conjugates. Overlaid plots of fluo-4 levels of HEL-binding B cells from control (gray) and RCd21cremDELloxp (blue) mice are shown. A representative plot is shown from two independent experiments (n=2-3 per experimental group). C, Live HEL-binding cells in culture based on forward side scatter flow cytometry analysis. Data from two independent experiments (n=2-3 per experimental group, error bars are SD, **P < 0.005) are shown. D, Flow cytometry analysis of intracellular Bim levels in B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp and control spleens (B220+ gated). Bimhigh HEL-binding cell population is outlined in black. Representative plots shown from three independent experiments (n=2-5 per experimental group). E, Frequencies of dUTP-labeled HEL-binding and non-HEL-binding B cells in the spleen. Representative plots from two independent experiments (n=3 per experimental group, *P < 0.05).

Despite intact proximal BCR signaling, the decreased frequency of HEL-binding B cells in Cd21cremDELloxp mice suggests that these cells may have a survival defect. To test this possibility, B cells from control and RCd21cremDELloxp mice were cultured in the presence of soluble HEL or DEL and survival was measured by determining the percent of live cells in culture by flow cytometry. We found that B cells from Cd21cremDELloxp mice showed diminished survival following BCR stimulation (Figure 5C). Furthermore, when purified B cells from SWHEL mice were adoptively transferred into control or Cd21cremDELloxp recipients reconstituted with C57/BL6 bone marrow, HEL-specific B cells obtained at 3.5 days post-transfer exhibited a much more accelerated loss in CD21CremDELloxp recipients than in controls lacking DEL (Figure S3C), indicating that they are rapidly eliminated. It has been reported that the pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is increased in anergic B cells and is a key factor in the elimination of self-reactive B cells (32, 33). Analysis of intracellular Bim expression in splenic B cells revealed that the low HEL-binding population in RCd21cremDELloxp mice expressed elevated amounts of Bim (Figure 5D). Consistent with increased Bim expression, TUNEL assay revealed that HEL-binding B cells from RCd21cremDELloxp mice were more prone to apoptosis (Figure 5E).

BAFF does not rescue self-reactive B cells

Studies in mouse models have shown that anergic B cells can be rescued from apoptosis with excess BAFF, and that BAFF signaling leads to Bim phosphorylation and degradation (34-36). Moreover, elevated serum BAFF levels are present in patients with autoimmune diseases such as SLE, RA, and Sjogren’s syndrome (37). To determine if excess BAFF can rescue HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice, soluble BAFF was injected into the peritoneum of RCd21cremDELloxp mice for six consecutive days, as described (38). The frequency of HEL-binding B cells in the spleen was assessed on the seventh day after the initial BAFF injection. Although exogenous BAFF promoted the accumulation of naïve B cells, the frequency of self-reactive, HEL-binding B cells was similar in RCd21cremDELloxp recipients injected with BAFF or PBS (Figure 6A).

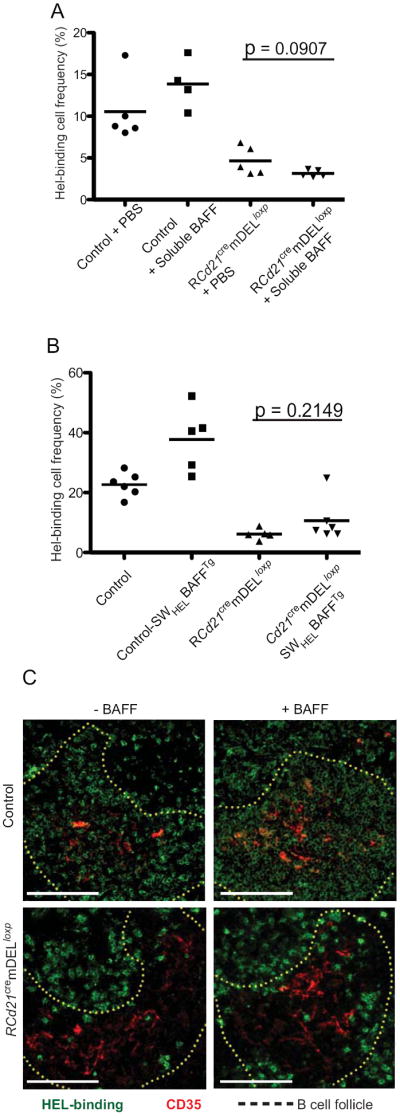

Figure 6. Provision of excess BAFF does not rescue self-reactive B cells in mice expressing mDEL.

A, SWHEL BM-reconstituted Cd21cremDELloxp (RCd21cremDELloxp) and control mice received intraperitoneal injections of soluble human BAFF or PBS for six consecutive days. The frequency of HEL-binding B cells in the spleen was assessed by flow cytometry (gated on B220+ cells). B, Cd21cremDELloxp and control mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with BM from SWHEL mice (RCd21cremDELloxp and control mice) or SWHELBAFFTg mice (Cd21cremDELloxSWHELBAFFTg and control-SWHELBAFFTg). Eight to 10 weeks after reconstitution, the frequency of HEL-binding B cells in the spleen was assessed by flow cytometry (gated on B220+ cells). Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n=2-3 per experimental group). C, Splenic sections were imaged from RCd21cremDELloxp, Cd21cremDELloxSWHELBAFFTg, control-SWHELBAFFTg, and control mice. HEL-binding cells (green) and FDCs (CD35+, red) were visualized in splenic sections with the B cell follicular region indicated by dotted lines. Scale bar, 100 μm

Since acute delivery of excess BAFF did not rescue HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice, we investigated whether chronic elevated BAFF levels would support the survival of HEL-binding B cells in RCd21cremDELloxp mice. To this end, SWHEL mice were intercrossed with a strain of BAFF transgenic mice (BAFFTg) that express BAFF in the myeloid compartment (26). Bone marrow from SWHELBAFFTg mice was used to reconstitute irradiated Cd21cremDELloxp (Cd21cremDELloxSWHELBAFFTg) or control mice (control-SWHELBAFFTg). These experiments revealed that while excess BAFF promoted the accumulation of naïve B cells (Figure 6B), no significant difference was noted in the frequency or localization of HEL-binding splenic B cells between Cd21cremDELloxSWHELBAFFTg and RCd21cremDELloxp mice (Figure 6B, C). Thus, excess BAFF does not alter the fate of transitional B cells recognizing FDC-bound self-antigen.

Discussion

Here we report that FDC-bound self-antigen eliminates self-reactive B cells at the transitional stage, providing a cellular context for peripheral tolerance events in the spleen. While the T1 B cell subset remains intact, a sharp reduction of self-reactive T2 B cells is observed, indicating failed progression from the T1 to T2 stage. This model is the first to show that late-stage self-reactive transitional B cells can be eliminated in the spleen where B cells complete maturation and collaborate with other cell types to mount an immune response. It is also the first model to show that self-antigen retained specifically on FDCs can mediate sustained and effective elimination of self-reactive B cells, preventing their entry into the long-lived pool of recirculating B cells. As such, this model will provide a valuable system to investigate the molecular cues regulating the T1-T2 checkpoint.

B cells are highly mobile both within and between the lymphoid tissues. Thus, the physiologic context of antigen recognition is an evolving landscape. In addition, effects of antigen filtration, opsonization and cell-associated transport impact where and how B cells recognize cognate antigen (39). FDCs are strategically located within the B cell follicle and have the unique capacity to retain antigens for extended periods (40). Indeed, the individual antigen transport functions of marginal zone macrophages, dendritic cells, and even non-cognate B cells facilitate the process of antigen delivery to FDCs. In addition, expression of CXCL13 and VCAM/ICAM promotes the association of B cells and FDCs to facilitate recognition of cognate antigen. In the context of the germinal center response, B cells compete for FDC-displayed antigen, resulting in the selection of high affinity B cells for subsequent differentiation into memory B cells and plasma cells (41). FDCs are also important for marking apoptotic cells for engulfment by macrophages (42), and a recent study showed that presentation of shed placental material specifically retained on FDCs can tolerize antigen-specific T cells (43).

Our studies raise the possibility that FDCs may also serve an important function in the long-term retention and display of self-antigens. In this scenario, newly formed self-reactive B cells would be eliminated in the spleen, even under circumstances where the exposure to self-antigen was transient or episodic. There are some correlative observations that are consistent with a role for FDCs in promoting B cell tolerance. (1) Self-reactive IgG-expressing memory B cells and plasma cells are generated as a byproduct of random V gene diversification in the germinal center (44, 45). Thus, autoantigen-containing immune complexes could be retained by FDCs. (2) Complement deficiencies are associated with lupus-like symptoms in humans and mice, which has been attributed to a failure to clear immune complexes as well as direct effects on B cell selection (46). (3) Fcγ-RIIB is an important negative regulator of B cell activation via the BCR, and its loss results in impaired B cell tolerance (47, 48). However, it remains to be determined if Fcγ-RIIB-mediated retention of self-antigens by FDCs also contributes to the maintenance of B cell tolerance (49).

After leaving the bone marrow, a transitional B cell requires approximately two days to become a mature recirculating B cell (50). The striking differences in the responses of T1 versus mature B cells in response to BCR engagement and other factors indicate distinct genetic programs. This supposition is supported by recent studies examining microRNA (miRNA) expression in immature, transitional, and mature B cell subsets (51). Immature IgM+ B cells in the BM have a miRNA signature that is highly divergent from that of T1 cells, suggesting the influence of microenvironmental factors such as BAFF in regulating miRNA expression. Although T1 cells undergo apoptosis in response to BCR engagement, they require signaling via the BAFF-R to mature to the T2 stage (52, 53). Previous work has shown that elevated BAFF can break tolerance of self-reactive B cells depending on the B cell stage of arrest (34, 36). In this regard, SWHEL B cells that were exposed to membrane HEL during development in the bone marrow were not rescued in the presence of increased BAFF levels (34), consistent with the fact that BAFF-R expression is induced at the transitional stage of B cell development (52, 54). On the other hand, HEL-binding B cells exposed to soluble HEL during development could mature into follicular and marginal zone B cells when BAFF is overexpressed, indicating a breach in tolerance (34, 55). Moreover, elevated BAFF could also rescue self-reactive B cells in pAlb mice in which self-antigen encounter occurs exclusively in the liver (4). We show that late transitional self-reactive B cells encountering membrane-bound self-antigen on FDCs are BAFF-responsive yet do not survive, even when BAFF is overexpressed. These results reinforce the notion that increased BAFF levels do not overcome the apoptotic signals (Bim) from repeated antigen encounter on FDCs, and suggest that the frequency and quality of antigen encounter, along with the developmental stage of the B cell, dictate survival or elimination in the spleen.

Despite the strong impact of the developmental block at the T1→T2 stage, we found that some self-reactive HEL-binding B cells escaped or were not subjected to negative selection at this checkpoint and showed evidence of antigen experience indicated by BCR downregulation and upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules and activation markers. Nonetheless, these cells were unable to productively interact with cognate T cells to induce T cell proliferation. These results suggest that these self-reactive B cells are impaired in antigen presentation capabilities, despite their localization in the outer PALS where productive responses to foreign antigens occur. Another important factor in determining the outcome of T cell interaction with tolerant B cells is timing. Cooke et al. determined that the avidity or quality of antigen binding determines the length of the “window of opportunity” for productive T cell interaction (56). A similar window of T cell help following antigen encounter has been proposed for transitional B cells based upon in vitro studies (57). Extrapolating from our findings as well as prior microscopy studies (58), we propose that sustained and iterative high-avidity interactions with FDC-bound antigen may irreversibly program the self-reactive B cells for apoptosis.

In summary (Figure S4), we envision a developmental pathway in which T1 B cells that have not previously encountered self-antigen in the bone marrow continue maturing towards T2 B cells and enter the follicle to encounter self-antigen on the extended processes of the FDCs. This encounter results in the failed progression to, or rapid elimination of, self-reactive T2 B cells. Due to low abundance of antigen or B cell migration pattern, some of the self-reactive B cells may not encounter self-antigen until a later stage of maturation, becoming partially activated and instructed to move to the outer PALS. Repetitive encounters with self-antigen on FDCs may result in increased Bim protein in these partially activated self-reactive B cells, thereby promoting their elimination by apoptosis. Alternatively, they may not be competent to elicit T cell help, or may undergo active elimination by T cells. Thus, these studies introduce retention of peripheral self-antigens as a facet of FDC function that could serve to eliminate self-reactive B cells newly arriving from the bone marrow.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Gavin/D. Nemazee (The Scripps Research Institute) for providing the BAFF transgenic mice, P. Stern and R. Hynes (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for providing the LB2-FLIP vector, L. Wang and the Animal Facility at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute for animal care, and members of the Rickert laboratory for assistance and discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI098304 and AI041649 to R.C.R. I.Y. was supported by NIH training grant DK007202. J.J. was supported by a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BAFF

B cell activating factor belonging to the TNF family

- DEL

duck egg lysozyme

- FDCs

follicular dendritic cells

- HEL

hen egg lysozyme

- MD4

anti-HEL Ig transgenic

- mDEL

membrane-bound duck egg lysozyme

References

- 1.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant Autoantibody Production by Early Human B Cell Precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basten A, Silveira PA. B-cell tolerance: mechanisms and implications. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2010;22:566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akkaraju S, Canaan K, Goodnow CC. Self-reactive B cells are not eliminated or inactivated by autoantigen expressed on thyroid epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2005–2012. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ota T, Ota M, Duong BH, Gavin AL, Nemazee D. Liver-expressed Ig{kappa} superantigen induces tolerance of polyclonal B cells by clonal deletion not {kappa} to {lambda} receptor editing. J Exp Med. 2011;208:617–629. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell DM, Dembic Z, Morahan G, Miller JF, Burki K, Nemazee D. Peripheral deletion of self-reactive B cells. Nature. 1991;354:308–311. doi: 10.1038/354308a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuels J, Ng YS, Coupillaud C, Paget D, Meffre E. Impaired early B cell tolerance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1659–1667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurasov S, Wardemann H, Hammersen J, Tsuiji M, Meffre E, Pascual V, Nussenzweig MC. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:703–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6834–6840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung JB, Sater RA, Fields ML, Erikson J, Monroe JG. CD23 defines two distinct subsets of immature B cells which differ in their responses to T cell help signals. Int Immunol. 2002;14:157–166. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loder F, Mutschler B, Ray RJ, Paige CJ, Sideras P, Torres R, Lamers MC, Carsetti R. B cell development in the spleen takes place in discrete steps and is determined by the quality of B cell receptor-derived signals. J Exp Med. 1999;190:75–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su TT, Rawlings DJ. Transitional B lymphocyte subsets operate as distinct checkpoints in murine splenic B cell development. J Immunol. 2002;168:2101–2110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed D, Benschop RJ, Cambier JC, Nemazee D. Developmental Regulation of B Lymphocyte Immune Tolerance Compartmentalizes Clonal Selection from Receptor Selection. Cell. 1998;92:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monroe JG, Dorshkind K. Fate decisions regulating bone marrow and peripheral B lymphocyte development. Adv Immunol. 2007;95:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)95001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajenoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, Germain RN. Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity. 2006;25:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen CD, Cyster JG. Follicular dendritic cell networks of primary follicles and germinal centers: phenotype and function. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Cho B, Suzuki K, Xu Y, Green JA, An J, Cyster JG. Follicular dendritic cells help establish follicle identity and promote B cell retention in germinal centers. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1084/jem.20111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo W, Smith D, Aviszus K, Detanico T, Heiser RA, Wysocki LJ. Somatic hypermutation as a generator of antinuclear antibodies in a murine model of systemic autoimmunity. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:2225–2237. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiller T, Tsuiji M, Yurasov S, Velinzon K, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Autoreactivity in Human IgG+ Memory B Cells. Immunity. 2007;26:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavoie TB, Drohan WN, Smith-Gill SJ. Experimental analysis by site-directed mutagenesis of somatic mutation effects on affinity and fine specificity in antibodies specific for lysozyme. J Immunol. 1992;148:503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gammon G, Shastri N, Cogswell J, Wilbur S, Sadegh-Nasseri S, Krzych U, Miller A, Sercarz E. The choice of T-cell epitopes utilized on a protein antigen depends on multiple factors distant from, as well as at the determinant site. Immunol Rev. 1987;98:53–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern P, Astrof S, Erkeland SJ, Schustak J, Sharp PA, Hynes RO. A system for Cre-regulated RNA interference in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13895–13900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806907105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer O, Tiscornia G, Ikawa M, Verma IM. Rapid generation of knockdown transgenic mice by silencing lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:286–292. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraus M, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky N, Rajewsky K. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/beta heterodimer. Cell. 2004;117:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phan TG, Amesbury M, Gardam S, Crosbie J, Hasbold J, Hodgkin PD, Basten A, Brink R. B cell receptor-independent stimuli trigger immunoglobulin (Ig) class switch recombination and production of IgG autoantibodies by anergic self-reactive B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:845–860. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavin AL, Duong B, Skog P, Ait-Azzouzene D, Greaves DR, Scott ML, Nemazee D. deltaBAFF, a splice isoform of BAFF, opposes full-length BAFF activity in vivo in transgenic mouse models. J Immunol. 2005;175:319–328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Victoratos P, Lagnel J, Tzima S, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M, Kollias G. FDC-specific functions of p55TNFR and IKK2 in the development of FDC networks and of antibody responses. Immunity. 2006;24:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allman DM, Ferguson SE, Lentz VM, Cancro MP. Peripheral B cell maturation. II. Heat-stable antigen(hi) splenic B cells are an immature developmental intermediate in the production of long-lived marrow-derived B cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:4431–4444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cambier JC, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Vilen BJ. B-cell anergy: from transgenic models to naturally occurring anergic B cells? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang J, Jackson M, Teyton L, Brunmark A, Kane K, Nemazee D. B cells are exquisitely sensitive to central tolerance and receptor editing induced by ultralow affinity, membrane-bound antigen. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;184:1685–1697. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reif K, Ekland EH, Ohl L, Nakano H, Lipp M, Forster R, Cyster JG. Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature. 2002;416:94–99. doi: 10.1038/416094a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enders A, Bouillet P, Puthalakath H, Xu Y, Tarlinton DM, Strasser A. Loss of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim inhibits BCR stimulation-induced apoptosis and deletion of autoreactive B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1119–1126. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliver PM, Vass T, Kappler J, Marrack P. Loss of the proapoptotic protein, Bim, breaks B cell anergy. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:731–741. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, Amesbury M, Basten A, Mackay F, Brink R. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity. 2004;20:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craxton A, Draves KE, Gruppi A, Clark EA. BAFF regulates B cell survival by downregulating the BH3-only family member Bim via the ERK pathway. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1363–1374. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesley R, Xu Y, Kalled SL, Hess DM, Schwab SR, Shu H-B, Cyster JG. Reduced Competitiveness of Autoantigen-Engaged B Cells due to Increased Dependence on BAFF. Immunity. 2004;20:441–453. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Townsend MJ, Monroe JG, Chan AC. B-cell targeted therapies in human autoimmune diseases: an updated perspective. Immunol Rev. 237:264–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodyear CS, Corr M, Sugiyama F, Boyle DL, Silverman GJ. Cutting Edge: Bim is required for superantigen-mediated B cell death. J Immunol. 2007;178:2636–2640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cyster JG. B cell follicles and antigen encounters of the third kind. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:989–996. doi: 10.1038/ni.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tew JG, Mandel T. The maintenance and regulation of serum antibody levels: evidence indicating a role for antigen retained in lymphoid follicles. J Immunol. 1978;120:1063–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aydar Y, Sukumar S, Szakal AK, Tew JG. The influence of immune complex-bearing follicular dendritic cells on the IgM response, Ig class switching, and production of high affinity IgG. J Immunol. 2005;174:5358–5366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kranich J, Krautler NJ, Heinen E, Polymenidou M, Bridel C, Schildknecht A, Huber C, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Zinkernagel R, Miele G, Aguzzi A. Follicular dendritic cells control engulfment of apoptotic bodies by secreting Mfge8. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1293–1302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCloskey ML, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Carroll MC, Erlebacher A. Acquisition and presentation of follicular dendritic cell-bound antigen by lymph node-resident dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;208:135–148. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Kofer J, Yurasov S, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Differential regulation of self-reactivity discriminates between IgG+ human circulating memory B cells and bone marrow plasma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18044–18048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113395108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mietzner B, Tsuiji M, Scheid J, Velinzon K, Tiller T, Abraham K, Gonzalez JB, Pascual V, Stichweh D, Wardemann H, Nussenzweig MC. Autoreactive IgG memory antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus arise from nonreactive and polyreactive precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9727–9732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803644105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carroll MC. The role of complement in B cell activation and tolerance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:61–88. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tiller T, Kofer J, Kreschel C, Busse CE, Riebel S, Wickert S, Oden F, Mertes MMM, Ehlers M, Wardemann H. Development of self-reactive germinal center B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune FcγRIIB-deficient mice. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207:2767–2778. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baerenwaldt A, Lux A, Danzer H, Spriewald BM, Ullrich E, Heidkamp G, Dudziak D, Nimmerjahn F. Fcγ receptor IIB (FcγRIIB) maintains humoral tolerance in the human immune system in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:18772–18777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111810108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharp PEH, Martin-Ramirez J, Boross P, Mangsbo SM, Reynolds J, Moss J, Pusey CD, Cook HT, Tarzi RM, Verbeek JS. Increased incidence of anti-GBM disease in Fcgamma receptor 2b deficient mice, but not mice with conditional deletion of Fcgr2b on either B cells or myeloid cells alone. Molecular Immunology. 2012;50:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allman DM, Ferguson SE, Cancro MP. Peripheral B cell maturation. I. Immature peripheral B cells in adults are heat-stable antigenhi and exhibit unique signaling characteristics. Journal of Immunology. 1992;149:2533–2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spierings DC, McGoldrick D, Hamilton-Easton AM, Neale G, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, Green DR, Withoff S. Ordered progression of stage-specific miRNA profiles in the mouse B2 B-cell lineage. Blood. 2011;117:5340–5349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schiemann B, Gommerman JL, Vora K, Cachero TG, Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, Frew E, Scott ML. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science. 2001;293:2111–2114. doi: 10.1126/science.1061964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rickert RC, Jellusova J, Miletic AV. Signaling by the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily in B-cell biology and disease. Immunological Reviews. 2011;244:115–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross JA, Dillon SR, Mudri S, Johnston J, Littau A, Roque R, Rixon M, Schou O, Foley KP, Haugen H, McMillen S, Waggie K, Schreckhise RW, Shoemaker K, Vu T, Moore M, Grossman A, Clegg CH. TACI-Ig neutralizes molecules critical for B cell development and autoimmune disease. impaired B cell maturation in mice lacking BLyS. Immunity. 2001;15:289–302. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lesley R, Xu Y, Kalled SL, Hess DM, Schwab SR, Shu HB, Cyster JG. Reduced competitiveness of autoantigen-engaged B cells due to increased dependence on BAFF. Immunity. 2004;20:441–453. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooke MP, Heath AW, Shokat KM, Zeng Y, Finkelman FD, Linsley PS, Howard M, Goodnow CC. Immunoglobulin signal transduction guides the specificity of B cell-T cell interactions and is blocked in tolerant self-reactive B cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:425–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sater RA, Sandel PC, Monroe JG. B cell receptor-induced apoptosis in primary transitional murine B cells: signaling requirements and modulation by T cell help. International Immunology. 1998;10:1673–1682. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki K, Grigorova I, Phan TG, Kelly LM, Cyster JG. Visualizing B cell capture of cognate antigen from follicular dendritic cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:1485–1493. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.