Abstract

Lower levels of parent–child affective flexibility indicate risk for children’s problem outcomes. This short-term longitudinal study examined whether maternal depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility and positive affective content in mother–child problem-solving interactions at age 3.5 years (N=100) and whether these maternal and dyadic factors predicted child emotional negativity and behaviour problems at a 4-month follow-up. Dyadic flexibility and positive affect were measured using dynamic systems-based modelling of second-by-second affective patterns during a mother–child problem-solving task. Results showed that higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility, which predicted children’s higher levels of negativity and behaviour problems as rated by teachers. Mothers’ ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems were predicted by their own depressive symptoms and individual child factors, but not by dyadic flexibility. There were no effects of dyadic positive affect. Findings highlight the importance of studying patterns in real-time dyadic parent–child interactions as potential mechanisms of risk in developmental psychopathology.

Keywords: parent–child interaction, flexibility, dynamic systems, depressive symptoms, behaviour problems

Maternal depression has been well documented as a risk factor in the development of child behaviour and adjustment problems (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Goodman, 2007). Maternal depression is associated with children’s emotional reactivity, deficits in self-regulation, and aggressive behaviour in the early childhood period (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Zahn-Waxler, Iannotti, Cummings, & Denham, 1990). Young children seem to be especially sensitive to the effects of maternal depression, as effect sizes between maternal depression and child behaviour are strongest in studies of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers (Connell & Goodman, 2002; Goodman et al., 2011). It is not only mothers’ clinical levels of depression but also mothers’ depressive symptoms that are associated with children’s elevated levels of behaviour problems (Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion, & Wilson, 2008; Hoffman, Crnic, & Baker, 2006; Luoma et al., 2001).

Parenting and parent–child interaction are the central mechanisms by which maternal depression and depressive symptoms influence child behaviour problems (Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005; Elgar, Mills, McGrath, Waschbusch, & Brownridge, 2007; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Depressed mothers are apt to express higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect with their children (Tronick & Reck, 2009), and infants show increased negativity to maternal depressed affect, even when depressed affect is simulated (Cohn & Tronick, 1983). In observed interactions, depressed mother–child dyads experience higher rates of conflict during problem-solving tasks, and depressed mothers are more likely to use negative parenting practices (e.g. criticism and scolding) during such tasks (Caughy, Huang, & Lima, 2009). Higher levels of observed negativity (Dietz, Jennings, Kelley, & Marshal, 2009) and lower levels of positivity (Foster, Garber, & Durlak, 2008) in parent–child interactions have been shown to mediate the relation between maternal depression and children’s externalizing problems. In fact, the combined effects of maternal depressive symptoms and observed parent–child negativity influence children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviours up to 7 to 10 years later, controlling for contextual risks (Leckman-Westin, Cohen, & Stueve, 2009). Collectively, this research offers evidence that parent–child interactions can be compromised and that children are more likely to manifest negativity and behavioural problems in families of mothers with depression or depressive symptoms (Cummings & Davies, 1994). However, there is more to learn about the specific mechanisms by which these interactions transmit risk for child behaviour problems.

Dyadic Interaction Patterns as Markers of Parent and Child Risk

Understanding the process by which parental depressive symptoms influence the development of child behaviour problems requires consideration of the proximal, reciprocal interactions between parent and child, as these dynamic interactions shape and constrain future outcomes (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). Coercion theory and related empirical work (Dishion, Patterson, & Kavanagh, 1992; Patterson & Bank, 1989; Patterson, DeGarmo, & Forgatch, 2004) have illustrated how the transactional, maladaptive parent–child interaction patterns characteristic of families with aggressive children become increasingly stable and lay the foundation for the development of child behaviour problems. Dynamic systems-based research has illustrated these self-organizing processes through the real-time modelling of microlevel parent–child interaction patterns, whereby recurring negative and rigid patterns of interaction are associated with children’s higher levels of externalizing behaviour problems (Dumas, Lemay, & Dauwalder, 2001; Granic & Patterson, 2006; Lunkenheimer & Dishion, 2009). However, although parent–child interactions characterized by hostility and coercion have been well modelled in the literature, we know considerably less about the dynamic, parent–child interactions of parents with depressive symptoms and corresponding child outcomes.

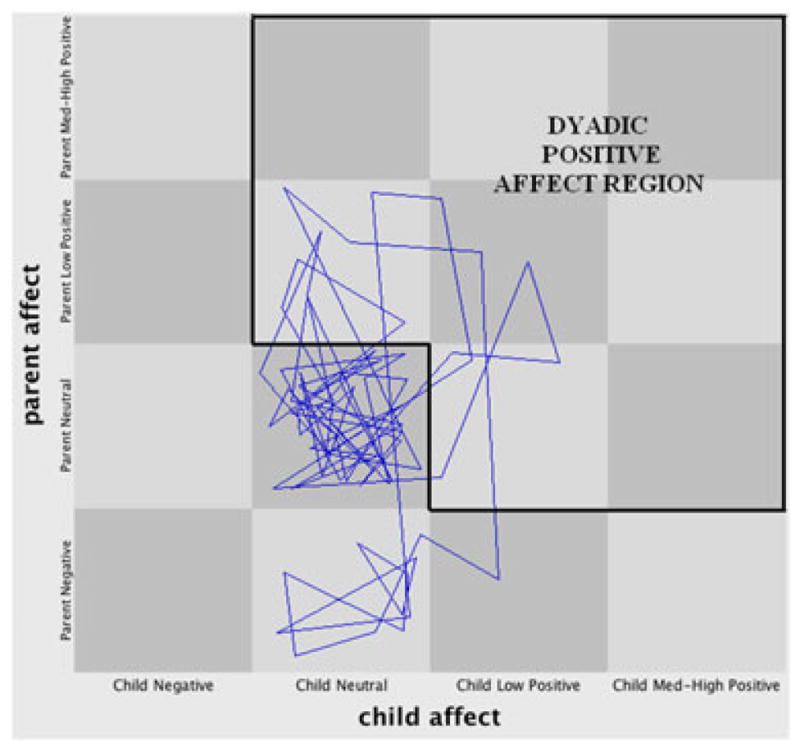

Affective flexibility (and its opposite, rigidity) are dynamic aspects of parent–child interaction that have been shown to act as mechanisms in the transmission of risk from parent to child (Granic & Lamey, 2002; Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Snyder, 2004). Affective flexibility has been measured using the dynamic systems-based methodology of state space grids (SSG) (Lewis, Lamey, & Douglas, 1999; please see Figure 1 for an example of an SSG). SSGs allow for the visualization and modelling of dyadic interaction patterns as they play out in real time. Affective states on an ordinal scale (e.g. negative, neutral, and positive affects) are plotted along the x-axis for one dyad member and the y-axis for the other. Consequently, the trajectory made up of sequential dyadic states (e.g. from mother neutral, child positive in one time unit to mother neutral, and child neutral in the next) can be plotted on the grid. With this method, affective flexibility has been defined as one or more of the following SSG indices: (i) the range of dyadic affective states that parent and child make use of, where greater flexibility is the use of a broader range of dyadic affective states at varying levels of intensity; (ii) the dispersion or even distribution of dyadic affective states across the possible repertoire of states, where greater flexibility is the more evenly distributed use of affective states; and (iii) the transitions from one dyadic affective state to another, where greater flexibility is the greater tendency to transition from one state to another. Conversely, low flexibility is defined as a diminished affective repertoire, a tendency to get stuck in particular affective states, or fewer transitions among affective states (Hollenstein, 2007). In the present study, flexibility was operationalized as the rate of transitions among positive, neutral, and negative affective dyadic states during parent–child interaction using SSG analysis (Lewis et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

A sample state space grid of dyadic interaction from one mother–child dyad, with the dyadic positive affect region highlighted.

In theory, higher dyadic flexibility should indicate that interaction partners are able to modulate the intensity or type of their affect to meet the desired goal of the interaction (Lunkenheimer, Olson, Hollenstein, Sameroff, & Winter, 2011). For example, when attempting to gain children’s attention or compliance, parents may need to move from a neutral state to a positive affective state to make the task more appealing or, conversely, help children downregulate high positive affect to assist them in focusing on the task at hand. Higher levels of affective flexibility also indicate that a range of affective experiences is present, which may provide children the opportunity to repair negative interactions and learn corresponding emotion regulation skills (Lunkenheimer, Hollenstein, Wang, & Shields, 2012). Research has demonstrated that a higher degree of affective flexibility is generally adaptive, related to positive affective content and lower levels of child behaviour problems (Granic, O’Hara, Pepler, & Lewis, 2007; Lunkenheimer et al., 2011). Related research using other methodologies has also supported the notion that the adaptive patterning and structure of parent–child interactions (e.g., higher levels of reciprocity and positive contingencies) are associated with children’s lower levels of behaviour problems in early and middle childhood (Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Deater-Deckard, Atzaba-Poria, & Pike, 2004; Harrist, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 1994; Mize & Pettit, 1997). Conversely, lower levels of affective flexibility have been shown to act as a risk mechanism in families characterized by conflict and hostility, related to higher levels of child behaviour problems (Dumas et al., 2001; Granic & Lamey, 2002; Hollenstein et al., 2004).

To our knowledge, research has not examined dynamic systems-based patterns of affective flexibility in the dyadic interactions between children and their parents with depressive symptoms. One possibility is that, like families characterized by hostility, these dyads also show lower levels of affective flexibility, with a tendency to become ‘stuck’ among certain affective states. We know that parents with higher levels of depressive symptoms tend to show lower levels of positive affect and higher levels of negative affect in parent–child interactions (Tronick & Reck, 2009). They also display greater affective miscoordination in parent–child interactions (Weinberg, Olson, Beeghly, & Tronick, 2006) and are less likely to repair this miscoordination (Jameson, Gelfand, Kulcsar, & Teti, 1997). Further, they show greater difficulty with adaptation in times of stress (Downey & Coyne, 1990), which may impact their ability to adjust and coordinate their affect in response to their child’s needs in challenging parent–child interactions. Stressful parent–child interactions could also overwhelm the coping of young children (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001) and exacerbate the child’s difficulty in recovering from negative states during such interactions (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Finally, maternal depressive symptoms and low mother–child mutuality (operationalized as mutual responsiveness, shared positive affect, and explicit agreement) independently predict child maladjustment across the early childhood period (Ensor, Roman, Hart, & Hughes, 2012). Thus, extant research would suggest that parents with depressive symptoms have greater difficulty coordinating or adapting to challenging parent–child interactions, and thus, these parent–child dyads may demonstrate the lower levels of flexibility known to be associated with children’s negativity and behaviour problems.

The Present Study

This short-term longitudinal study examined whether maternal depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility and positive affect in mother–child problem-solving interactions at age 3.5 years (N= 100) and whether maternal depressive symptoms and dyadic flexibility predicted child emotional negativity and behaviour problems at a 4-month follow-up. We chose these child outcomes because emotional negativity (observed and reported) and behaviour problems have been specifically linked to both maternal depressive symptoms (Dietz et al., 2009; Leckman-Westin et al., 2009) and dyadic flexibility (Granic et al., 2007; Lunkenheimer et al., 2012) in prior research. Additionally, examining these outcomes together allowed us to investigate whether dyadic parent–child coregulatory processes predicted child dysregulation more broadly in early childhood.

From prior research indicating that conflict and hostility are related to lower affective flexibility (Hollenstein et al., 2004) and that parents’ depressive symptoms are related to difficulty coordinating and repairing affective interactions with their children (Jameson et al., 1997), it was hypothesized that higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms would relate to lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility. Given that prior research has typically studied affective content (e.g. degree of positive or negative affect) as a risk mechanism in depressed mother–child interactions, the effects of both affective flexibility and affective content were included and compared. Specifically, we examined positive affective content as a mechanism (rather than negative content) given that mothers with depressive symptoms tend to show lower levels of positive affect with their children (Tronick & Reck, 2009). Further, we expected to see more variation in positive than negative affect given that, on average, only about 5%to 10%of observed family interactions in laboratory settings are coded as aversive (Dishion, Duncan, Eddy, & Fagot, 1994).

To date, researchers have predominantly studied the dynamic systems-based construct of affective flexibility in families at higher risk or in clinical treatment (Granic et al., 2007). In contrast, the present study was designed to examine flexibility in relation to risk factors in typical families, to understand the role of dyadic flexibility as a potential risk or protective factor in parent–child interactions in early childhood. Additionally, prior research on affective flexibility has predominantly focused on older children and adolescents (e.g. Hollenstein & Lewis, 2006). However, parent–child affective flexibility may be particularly important during early childhood when children are developing the ability to modulate affective responses in interpersonal relationships. Thus, the present study sought to examine the effects of flexibility in parent–child interactions between ages 3 and 4 years, when children’s increases in more complex and flexible coping responses are thought to mark the emergence of self-regulatory competence (Olson, Sameroff, Lunkenheimer, & Kerr, 2009). Prior research has also demonstrated the importance of certain self-regulatory skills in the child that play a role in the relations between parent–child interactions and children’s negativity and behaviour problem outcomes, for example, the child’s effortful control (e.g. Eisenberg et al., 2005). We considered that children higher in effortful control might have an advantage in problem-solving tasks with parents that require the inhibition of impulses and the flexible modulation of affect in response to situational demands. Research has also shown that children low in effortful control are more likely to show symptoms of internalizing psychopathology in the context of negative or ill-fitting parenting (Kiff, Lengua, & Bush, 2011). Therefore, in all primary analyses, we controlled for the child’s effortful control and their baseline levels of observed negativity in predicting their later negativity and behaviour problems.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 100 children and their families (54% female children), with a racial makeup of 86% White, 8% biracial, 3% Asian, and 3% ‘other race’ children, and an ethnic makeup of 10% Hispanic or Latino children. Children were 41 months old on average (standard deviation = 3 months) at time 1 (T1) and 45 months old on average (standard deviation = 3 months) at time 2 (T2). Median annual family income was roughly $65 000, and mothers’ and fathers’ education was high on average (college graduate). Seventy-nine per cent of biological parents were married, 7% were cohabiting, 7% were single, 5% were separated or divorced, and 1% were remarried. Participants were recruited via flyers placed in local day care centres, preschools, and businesses, as well as through email LISTSERV of county agencies serving families with young children. Families were excluded if children had a pervasive developmental disorder or if parents or children had a heart condition that might interfere with physiological data collection.

Procedure

During a 2-h laboratory visit at T1, mothers filled out multiple questionnaires in the corner of the room while the child was completing behavioural tasks with the experimenter, including questionnaires on their own depressive symptoms and the child’s negativity and behaviour problems. During the visit, mothers and children also completed three dyadic behavioural tasks. These consisted of the following: (i) a free play task for 7 min, for which parents were simply instructed to ‘play as they normally would with their child’ with a variety of toys; (ii) a toy cleanup task for 4 min, for which parents were instructed to guide the child to clean up the toys with which they had just played, using only their words (i.e. not to physically clean up the toys for the child); and (iii) a problem-solving task for 6 min, which is described in more detail later. Mothers were compensated $50 for their involvement at T1. At T2, mothers and teachers completed multiple questionnaires online, including questionnaires on children’s negativity and behaviour problems. Mothers and teachers who completed the questionnaires were compensated with a $20 gift card to a local store, which was mailed to them.

Measures

Parent–Child Challenge Task

The Parent–Child Challenge Task was developed by the first author to study dyadic parent–child patterns during a challenging, problem-solving situation. Mothers and children engaged in a task for 6 min in which mothers were instructed to help their children complete a puzzle using only their words, but not to physically complete the task for the child. The puzzle was made of seven wooden pieces that fit together in multiple different configurations to create various castles. Mothers and children were instructed to work on three specific designs from a guidebook that increased in difficulty (easy, moderate, and difficult) as the task progressed. The task was designed to be challenging for both parents and children and therefore encourage persistence at a difficult task: after mother and child completed all three designs, the child would receive a prize. The baseline condition involved the dyad working on the puzzle with no time limit provided to the parent. However, after 4 min, the experimenter interrupted the task and ‘reminded’ parents that they only had 2 min left to finish, which initiated the stressor condition. After 2 min, the experimenter returned to conclude the task, saying, ‘I’m sorry, I realized I did not give you enough time to finish those puzzles, they were hard’, and awarded the child the prize. Thus, children received the prize regardless of whether the dyad completed all three designs or not. For the purposes of the present study, only the baseline portion of the task was analysed to understand relations among maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility and positive affect, and child negativity and behaviour problems in typical problem-solving interactions. Four families did not have Parent–Child Challenge Task data because of the dyad speaking a language other than English for some portion of the task (n = 2) and equipment malfunction (n = 2), resulting in a valid n of 96 dyads for whom we had mother–child interaction data.

Parent and child affect coding

Behavioural observations were recorded using the Noldus Observer XT 8.0 software and coded using the Dyadic Interaction Coding system Lunkenheimer, 2009, which was adapted from the Relationship Process Code 2.0 (Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004) and the Michigan Longitudinal Study (Olson & Sameroff, 1997) coding systems. Parents and children were each coded in real time on a second-by-second basis along two dimensions, affect and behaviour; for the purposes of the present study, only affect codes were examined. Two undergraduate and one graduate research assistants coded the data and were tested for reliability on 20% of the dataset in relation to a standard set by the first author and a trained graduate student. Reliability was calculated on an initial set of 10 videotapes, in addition to drift reliability assessed on an additional 10 tapes throughout the coding period. Interrater reliability analysis was performed in the Noldus Observer 8.0 XT using a standard 3-s window.

There were four codes that reflected verbal and nonverbal affect: negative affect, neutral affect, low positive affect, and medium–high positive affect. Although the same four affect codes were used for both parent and child, the scale of emotional intensity was different for parents and children, in that child affect codes accounted for the greater affective intensity typical of 3-year-olds as compared with adults. Negative affect referred to an expression, however small, of irritation, annoyance, distress, anger, disgust, sadness, discomfort, fear, nervousness, or anxiety. For parents, examples of negative affect included heavy sighs, eye rolling, sharp voice tone, frowning, or narrowed eyes. For children, examples of negative affect included stomping, crying, yelling in anger, frowning, or slumped shoulders. Neutral affect reflected the absence of verbal or nonverbal affective expression. Examples of neutral affect included a lack of eye contact, the absence of a particular facial expression (e.g. smile or frown), and/or a relatively flat vocal tone with few fluctuations or lilts. Low positive affect referred to the expression of low-intensity positive affect. Examples included positive lilts or warmth in vocal tone, a smile, and/or warm eye contact that conveyed interest or engagement. Medium–high positive affect referred to the expression of medium-intensity or high-intensity positive affect. Examples included larger fluctuations in vocal tone, such as the use of a high pitch to express excitement or gain the other’s attention, open-mouth smiles, laughing, giggling, singing, or hugging. Interrater agreement for the parent negative, neutral, low positive, and medium–high positive affect codes was 96%, 93%, 91%, and 91%, respectively. Interrater agreement for the child negative, neutral, low positive, and medium–high positive affect codes was 100%, 95%, 85%, and 85%, respectively.

Dyadic flexibility and dyadic positive affect

Dyadic affective flexibility and dyadic positive affect were derived using the aforementioned coding system and calculated using Gridware 1.15 (Lamey, Hollenstein, Lewis, & Granic, 2004). Parent and child affects were mapped onto SSGs (Lewis et al., 1999), with child affect along the x-axis and mother affect along the y-axis. There were four affect codes each for parent and child (negative, neutral, low positive, and medium–high positive affect), resulting in a 4×4 or 16-cell grid. The sequence of dyadic affective states was plotted as it proceeded in real time on the grid. An example of an SSG from one mother–child dyad is displayed in Figure 1.

Flexibility was operationalized as the rate of transitions among all dyadic affective states (negative, neutral, low positive, and high positive) during the problem-solving interaction. This equalled the total number of transitions the dyad made between different cells (i.e. different dyadic affective states) on the entire grid (Hollenstein, 2007), divided by the time of the interaction in minutes.

Dyadic positive affect was operationalized as the durational proportion of time the dyad spent in the positive affect region of the SSG (Figure 1). This nine-cell region included all dyadic affective states where both parent and child were displaying positive affect and also dyadic affective states where one partner was displaying positive affect and the other partner was neutral. The decision to use this region of the grid was based on a prior work showing that typical parents and children tend to be mismatched (Tronick & Cohn, 1989), alternating between neutral and positive affects during dyadic interactions (Dishion, Andrews, & Crosby, 1995). In contrast, parent–child interactions characterized by higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms have been shown to display higher levels of shared neutral and/or negative affect (e.g. Downey & Coyne, 1990).

Maternal depressive symptoms

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed via self-report on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) at T1. The 20-item questionnaire was designed specifically to assess depressed symptomology in the general population and has demonstrated high internal consistency and adequate test–retest reliability (Radloff, 1977). Participants filled out items according to how many times they had felt a certain way during the past week (e.g., ‘I felt that people disliked me’), where ‘0’ = rarely or none of the time, ‘1’ = some or a little of the time, ‘2’ = occasionally or a moderate amount of time, and ‘3’ =most or all of the time. The participant’s sum score represented their level of depressive symptoms (possible range = 0 to 60). Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.72. Eleven mothers met the criteria for clinical depression based on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale cut-off score of 16.

Observed negativity

Children’s observed negativity was used as a control variable, to account for baseline levels of observed negativity with their caregiver at T1 when predicting caregiver ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems at T2. Observed negativity was measured as the total number of instances that children displayed negative affect across the three parent–child dyadic tasks at the T1 laboratory assessment described previously (free play, cleanup, and the problem-solving tasks). Child negative affect was coded using the aforementioned affect coding system. The kappa value for child negative affect was 0.82.

Effortful control

Effortful control was used as a control variable, to account for individual differences in temperamental self-regulation that may have influenced the child’s ability to inhibit impulses and modulate behaviour in response to a caregiver-directed problem-solving task. Individual differences in effortful control were assessed using three observed laboratory tasks from Kochanska, Murray, Jacques, Koenig, & Vandegeest’s (1996) behavioural battery (described later). The tasks were the Tower Task, Snack Delay, and Lab Gift, administered in that order. Each behavioural task was designed to tap Rothbart’s (1989) general construct of effortful control, involving suppression of a dominant response and initiation of a subdominant response according to varying task demands. All tasks were introduced as ‘games’, and children were reminded of the rules midway through each task.

The Tower Task is designed to assess the child’s ability to suppress and initiate behaviours in a turn-taking situation. Each child was instructed to take turns with the experimenter in placing blocks one at a time to build a tower. There were two trials, and the proportion of turns correctly initiated by the child out of the total number of possible turns was averaged across the two trials. The Snack Delay is designed to assess the child’s ability to delay gratification and suppress and initiate impulses concerning food. The experimenter instructed the child that he or she could pick up a clear plastic cup and have the candy under it after the experimenter rang the bell. There were four trials with delay times of 10, 15, 20, and 30 s, respectively, and children were scored on their ability to delay various behaviours (touching the bell or cup or eating the candy) until after the experimenter had lifted and/or rung the bell. Scores were averaged across the four trials. The Gift Delay task is designed to assess the child’s ability to delay gratification and suppress and initiate impulses with respect to a desired object. The experimenter said that she had a present for the child but needed to wrap it first. The child was instructed not to look while the experimenter noisily wrapped the gift for 1 min; then, she placed the gift in front of the child and directed the child to wait without touching the gift while she left the room for 2 min to find a bow. Scores were based on an aggregate of the latencies to peek or touch the gift and the strategies used to peek at or touch the gift (e.g. touches, lifts, or fully opens the gift). Individual subtest scores were standardized and averaged to compute a total effortful control score (alpha = 0.79). Please see the work of Kochanska et al. (1996) for additional information on these tasks.

Externalizing and internalizing behaviour problem outcomes

Externalizing and internalizing behaviour problems were assessed via mother report at T2 using the Child Behavior Checklist (1.5–5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and via teacher report at T2 using the Caregiver–Teacher Report Form (1.5–5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The 99 items are rated on 3-point scales (‘2’ = very true or often true of the child; ‘1’ = somewhat or sometimes true; ‘0’ = not true of the child). The externalizing behaviour subscale reflects behavioural dysregulation in the form of poor attentional control and physically aggressive behaviour, whereas the internalizing subscale reflects dysregulation in the form of somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression. For externalizing, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.93 for mothers and 0.93 for teachers. For internalizing, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77 for mothers and 0.90 for teachers.

Emotional negativity outcomes

Child emotional negativity was assessed via mother report at T2 using the emotional lability/negativity subscale from the Emotion Regulation Checklist (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). The Emotion Regulation Checklist is a 24-item questionnaire that targets processes central to emotionality and regulation, including affective lability, intensity, valence, flexibility, and contextual appropriateness of affective displays. The emotional lability/negativity subscale represents a lack of flexibility, mood lability, and dysregulated affect. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale where ‘1’ = never, ‘2’ = sometimes, ‘3’=often, and ‘4’ = almost always; sample items include ‘Displays negative emotions when attempting to engage others in play’ and ‘Is prone to angry outbursts’. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.77 for mothers and 0.87 for teachers.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were performed to determine if the predictors of interest differed by sociodemographic factors. Maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic positive affect, and dyadic flexibility were not significantly related to maternal education, socioeconomic status, child gender, child race or ethnicity, or parents’ marital status. Child age was included as a control variable to account for variation in age at our T1 assessment. An additional planned control variable was the child’s effortful control, a measure of temperamental self-regulation that has been found to be an important factor in the relationship between parent–child interactions and child behaviour problems (Eisenberg et al., 2005), which also served to control for individual differences in the child’s ability to engage in and persist at a parent-directed problem-solving task. Another planned control variable was the child’s observed negativity in parent–child interactions at T1, to control for children’s baseline levels of negativity when predicting their negativity and behaviour problems at T2. Descriptive statistics for the resulting study variables are presented in Table 1. Bivariate correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive data

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 variables | |||

| Child age in months (n = 100) | 41.0 | 3.0 | 37.5–44.4 |

| Child effortful control (n = 98) | 0.00 | 0.70 | −2.56–1.36 |

| Child observed negativity (n = 98) | 1.43 | 1.81 | 0–8 |

| Maternal depressive symptoms (n = 100) | 7.53 | 7.27 | 0–45 |

| Dyadic flexibility in transitions per minute (n = 96) | 1.97 | 1.48 | 0–7.40 |

| Dyadic positive affect in seconds (n = 96) | 18.06 | 29.36 | 0–181.87 |

| Time 2 variables | |||

| Mother externalizing (n = 91) | 7.91 | 7.34 | 0–31 |

| Mother internalizing (n = 91) | 5.07 | 4.21 | 0–20 |

| Mother emotional negativity (n = 87) | 25.21 | 4.92 | 15–38 |

| Teacher externalizing (n = 67) | 8.01 | 8.97 | 0–41 |

| Teacher internalizing (n = 67) | 6.70 | 6.98 | 0–30 |

| Teacher emotional negativity (n = 67) | 24.07 | 6.17 | 15–48 |

Note: Mother = mother ratings; Teacher = teacher ratings; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child age | — | |||||||||||

| 2. Effortful control | 0.21* | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Observed negativity | −0.13 | −0.10 | — | |||||||||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | — | ||||||||

| 5. Dyadic flexibility | −0.10 | −0.16 | 0.21* | −0.26* | — | |||||||

| 6. Dyadic positive | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.15 | 0.27** | — | ||||||

| 7. Mother EXT | −0.18† | −0.30** | 0.08 | 0.19† | 0.07 | 0.03 | — | |||||

| 8. Mother INT | −0.07 | −0.30** | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.65*** | — | ||||

| 9. Mother NEG | −0.09 | −0.26* | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.03 | −0.14 | 0.70*** | 0.45*** | — | |||

| 10. Teacher EXT | −0.13 | −0.28* | 0.16 | 0.20† | −0.18† | −0.10 | 0.21† | 0.00 | 0.18 | — | ||

| 11. Teacher INT | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.56*** | — | |

| 12. Teacher NEG | −0.08 | −0.21† | 0.16 | 0.20 | −0.14 | −0.09 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.22† | 0.85*** | 0.49*** | — |

Note: EXT = externalizing behaviours; INT = internalizing behaviours; NEG= emotional negativity.

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<.001.

Bivariate correlations indicated that depressive symptoms were negatively correlated with dyadic flexibility, r =−0.26, p<0.05. Dyadic flexibility was marginally negatively associated with teacher ratings of externalizing problems at T2. Dyadic flexibility and dyadic positive affect were positively correlated (r=0.27, p<0.05). The control variables of child effortful control and observed negativity were significantly associated with children’s negativity and behaviour problem outcomes at T2, whereas child age was only marginally associated with behaviour problem outcomes. Among child outcomes at T2, child negativity was significantly positively intercorrelated with externalizing and internalizing ratings within mothers’ ratings (rs = 0.70 and 0.45, respectively, p<0.001) and within teachers’ ratings (rs = 0.85 and 0.49, respectively, p<0.001). Ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems at T2 were associated within rater but were only marginally correlated across rater.

Given the intercorrelations among negativity and behaviour problems within rater, these outcomes were aggregated into latent factors in subsequent primary analyses. Latent factors of negativity and behaviour problems were constructed in Mplus version 5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007, Los Angeles, CA) using full information maximum likelihood estimation, a method that accommodates missing data by estimating each parameter using all available data for that specific parameter. A confirmatory factor analysis model was performed to model separate latent factors of mothers’ ratings of negativity and behaviour problems (i.e. externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and emotional negativity) and teachers’ ratings of negativity and behaviour problems and the relationship between them. This model was an adequate fit to the data, χ2(8) = 12.06, ns, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)= 0.07, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.04. Standardized estimates of externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and emotional negativity for mothers’ ratings (1.00, 0.69, and 0.64, respectively) and teachers’ ratings (0.99, 0.86, and 0.55, respectively) were all significant at the p<0.001 level. In this model, the latent factors of mothers’ and teachers’ ratings were once again marginally related (Est. = 0.21, standard error (SE) = 0.12, p<0.10). Consequently, subsequent primary models were run separately by mothers’ ratings and teachers’ ratings of child outcomes.

Primary Analyses

The primary research question was whether higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility in parent–child interactions and whether these maternal and dyadic factors were related to children’s higher levels of negativity and behaviour problems. To put the role of dyadic flexibility (i.e. affective structure) in the context of extant research on affective content between parent and child, the testing of this question also involved examining and comparing the effects of dyadic flexibility with that of dyadic positive affect. Structural equation models were performed in Mplus version 5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007) using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Models were tested separately by mother and teacher ratings of child outcomes, resulting in two structural equation models. Each model included the control variables of child age, effortful control, and observed negativity at T1; maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility, and dyadic positive affect at T1; and a latent factor outcome of child negativity and behaviour problems at T2 (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and emotional negativity as rated by either mothers or teachers). Results will be presented first for mothers’ ratings of child outcomes and second for teachers’ ratings.

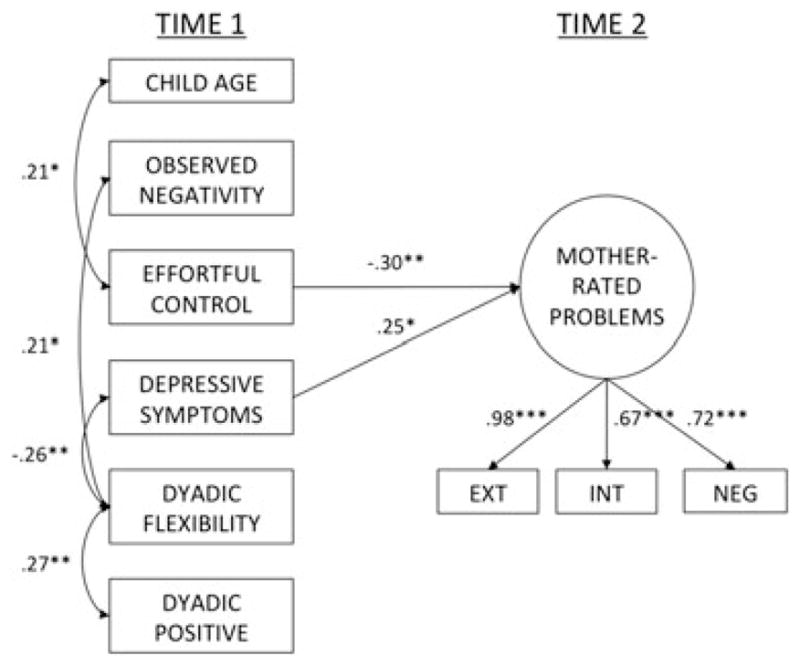

For the model of maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility, and dyadic positive affect predicting mother ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems, model fit was good, χ2(12) = 10.50, ns, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA= 0.00, SRMR = 0.03. Standardized model parameters for significant pathways are shown in Figure 2. Higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic flexibility but were not related to dyadic positive affect (Est. = −0.14, SE = 0.10, ns). Maternal depressive symptoms and child effortful control predicted child negativity and behaviour problems at T2, but neither dyadic flexibility (Est. = 0.05, SE = 0.11, ns) nor dyadic positive affect (Est. = 0.07, SE = 0.12, ns) predicted child outcomes at T2. Child negativity also did not predict child outcomes at T2 (Est. = −0.07, SE = 0.10, ns). Dyadic flexibility showed concurrent positive relations with dyadic positive affect and observed child negativity. Thus, with respect to mothers’ ratings of child outcomes, individual maternal and child factors predicted the child’s negativity and behaviour problems, but dyadic processes did not. This model explained 20% of the variance (Est. = 0.20, SE = 0.09, p<0.05) in the latent factor of mother-reported child negativity and behaviour problems. The variance explained for externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and emotional negativity was 94%, 46%, and 52%, respectively (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Effects of maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility, and dyadic positive affect on mothers’ ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems. Note: Non-significant paths are omitted. EXT = externalizing problems; INT = internalizing problems; NEG= emotional negativity.

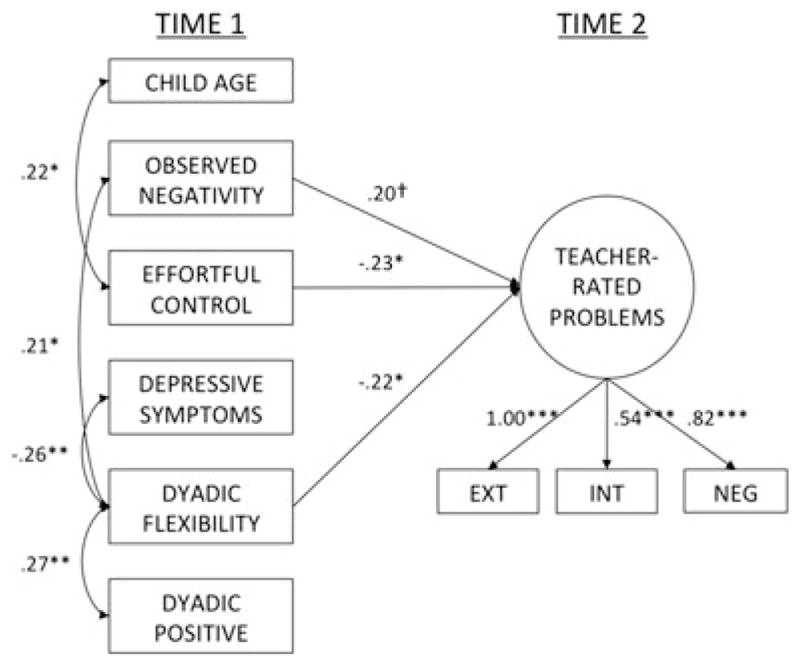

The model of maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility, and dyadic positive affect predicting teacher ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems showed a good fit to the data, χ2(12) = 11.33, ns, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA= 0.00, SRMR= 0.05. Standardized model parameters for significant pathways are shown in Figure 3. In this model, higher maternal depressive symptoms were once again related to lower dyadic flexibility but not dyadic positive affect (Est. = −0.14, SE= .10, ns). Lower dyadic flexibility predicted children’s higher levels of negativity and behaviour problems at T2, but maternal depressive symptoms (Est. = 0.11, SE = 0.12, ns) and dyadic positive affect did not (Est. = −0.02, SE = 0.09, ns). Child effortful control also predicted child negativity and behaviour problems at T2, and observed negativity at T1 was marginally predictive. Once again, dyadic flexibility was positively related to dyadic positive affect and observed child negativity at T1. Thus, with respect to teachers’ ratings of child outcomes, dyadic flexibility predicted children’s negativity and behaviour problems controlling for the effects of maternal depressive symptoms, child effortful control, and observed child negativity. This model explained 21% of the variance (Est. = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p<0.05) in the latent factor of teacher-reported child negativity and behaviour problems. The variance explained for externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and emotional negativity was 96%, 37%, and 75%, respectively (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Effects of maternal depressive symptoms, dyadic flexibility, and dyadic positive affect on teachers’ ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems. Note: Non-significant paths are omitted. EXT = externalizing problems; INT = internalizing problems; NEG = emotional negativity.

DISCUSSION

Recently, researchers have called for a focus on dynamic processes in the investigation of familial risk factors and children’s behavioural adjustment (Calkins, 2010; Granic & Patterson, 2006). With dynamic methods, dyadic interaction patterns between parent and child are emerging as important individual difference factors in developmental psychopathology (Granic & Hollenstein, 2003; Lunkenheimer & Dishion, 2009). The present study was designed to add to this growing body of research by determining whether dynamic systems-based measures of dyadic flexibility and positive affect were related to maternal depressive symptoms and children’s negativity and behaviour problems in early childhood. We found that mothers’ higher levels of depressive symptoms were related to lower levels of dyadic flexibility in parent–child problem-solving interactions at age 3.5 years. We also found that lower levels of dyadic flexibility (i.e. affective structure), but not dyadic positive affect (i.e. affective content), predicted later negativity and behaviour problems in early childhood. Although we could not test mediational developmental pathways because of the constraint of having only two assessment points, the present findings offer preliminary evidence that lower levels of dyadic flexibility between parent and child act as a potential mechanism of risk in families characterized by maternal depressive symptoms.

As hypothesized, mother–child dyads characterized by higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms showed lower dyadic flexibility during problem-solving tasks. This finding builds upon prior work illustrating that mothers with depression or depressive symptoms have difficulty with affective coordination with their children (Coyne, Downey, & Boergers, 1992; Feldman & Eidelman, 2007; Jameson et al., 1997; Tronick & Reck, 2009; Weinberg et al., 2006). It has also been suggested that depressive symptoms interfere with parents’ ability to process and appraise child behaviour and select appropriate emotional responses to that behaviour (Dix & Meunier, 2009). Thus, mothers with higher levels of depressive symptoms may have more difficulty flexibly adjusting their affect to assist their children in meeting the needs of problem-solving or goal-oriented situations. Correspondingly, these dyads may become stuck in a particular affective state or pattern, for example, a shared negative affective state or a mismatched affective state (e.g. the parent is negative whereas the child is positive). This evidence that typical parent–child dyads are more likely to become affectively ‘stuck’ when mothers have higher levels of depressive symptoms may have implications for prevention programmes. Mothers with depression are thought to become stuck in particular cognitive or behavioural patterns in parenting their children, and the parent’s generation of alternative solutions to problems has been shown to be effective in reducing children’s corresponding behaviour problems (Bugental, Corpuz, & Schwartz, 2012). This type of resource generation may also act as a preventive strategy for parents with depressive symptoms. Future work could address whether strategies that aim to improve parents’ cognitive flexibility may be partially impacting child outcomes through the enhancement of parent–child affective or behavioural flexibility during interactions with their children.

On the other hand, we did not find that lower levels of dyadic positive affect were associated with maternal depressive symptoms, even though depressed mothers have shown lower levels of positive affect on average in parent–child interactions in some studies (e.g. Downey & Coyne, 1990). Findings in the literature have been mixed: some studies show differences whereas others find that dyadic affective content does not differ by maternal depressive symptoms or depression diagnoses (e.g. Lovejoy, 1991; Weinberg, Beeghly, Olson, & Tronick, 2008). In light of our findings regarding flexibility, the null finding for positive affect may indicate that the affective content itself becomes less important once the structure or pattern of affect has been taken into account. Prior research would support the idea that the patterning of interactions, such as flexibility among positive and negative affective states (Lunkenheimer et al., 2012) or the repair from a negative to a positive state (Granic et al., 2007), is particularly important for children’s adaptive developmental and clinical outcomes. Collectively, the mixed findings for positive affect may also suggest that methodology makes a difference. Our assessment differed from prior research in that it was a dyadic affective variable based on dynamic systems methods. However, despite using an aggregate variable of the proportional duration of time spent in positive affective states, we still did not have the level of detail and corresponding power with which to detect significant effects. It is also possible that variation in overall levels of positive affect was constrained in a community sample.

Lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility predicted higher teacher ratings of children’s negativity and behaviour problems at follow-up, above and beyond the contributions of the child’s own effortful control and baseline negativity. This is an important finding, given the large contributions that the child’s temperamental self-regulation often make in comparable studies of the relations between parent–child interaction and children’s problem outcomes (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003). This finding echoes extant research indicating that low affective flexibility (high rigidity) in parent–child interactions is maladaptive and related to children’s problem outcomes (e.g. Dumas et al., 2001; Hollenstein et al., 2004). Although we have relatively little research to date using dynamic, real-time measures of parent–child interactions in the early childhood age range, they may provide an important tool for understanding the development of young children’s emotional and behavioural adjustment. Typical parent–child problem-solving interactions in early childhood should be characterized by higher levels of parental engagement (Cohn & Tronick, 1987) and dyadic affective flexibility (Lunkenheimer et al., 2011) as parent and child cycle among positive, neutral, and occasional negative affective states as they coordinate their behaviour towards a common goal. Theoretically, these affectively flexible interactions should allow for the development of young children’s emotional and behavioural regulation as they practise and internalize regulatory strategies with their parents. Conversely, lower levels of dyadic affective flexibility may constrain this early regulatory development and therefore heighten the risk of increased negativity and behaviour problems.

Dyadic processes were predictive of teachers’ but not mothers’ ratings of child negativity and behaviour problems. This was surprising, given that parent–child affective flexibility has been related to parental ratings of child problem behaviour in prior research (Granic et al., 2007). It is possible that the shared method variance between mothers’ ratings of their own depressive symptoms and their children’s problem behaviour was strong enough to obscure the effects of the dyadic factors in the model. It is also possible that dyadic flexibility has specific implications for children’s behavioural adjustment across settings, in other words, that the effect of reduced flexibility with parents hampers the child’s ability to coregulate their behaviour with other caregivers such as teachers. Children’s negativity and externalizing problems loaded more highly onto our latent construct of teacher-reported child outcomes than internalizing problems, which may also indicate that it is the more salient, observable aspects of child dysregulation that are affected by dyadic flexibility and that teachers are more likely to notice or report (Stanger & Lewis, 1993). Future research could address whether there is something particular to maternal depressive symptoms or child internalizing problems that prevented this pathway from emerging in models for mother reports in the present study.

The present study involved certain limitations. The sample was a typical, community sample, and therefore, levels of maternal depressive symptoms were low on average. This may have constrained our power with which to detect dyadic differences in flexibility and positive affect. Assessment was constrained to two points in time; thus, we could not fully address the emergence and stabilization of child behaviour problems as a result of transactions between maternal depressive symptoms and dynamic interaction patterns over-developmental time. Future research could examine transactional or mediational processes across multiple assessments; such a design could also address the longitudinal stability of dynamic parent–child interaction patterns during this developmental stage. Additionally, given that flexibility reflected the rate of affective changes regardless of content, it was difficult to confirm whether, for example, higher levels of flexibility represented an adaptive degree of transitions among various affective states or a more chaotic or disorganized affective profile. Thus, although the present study supported prior research, it will be important that future research also consider curvilinear models (i.e. the notion that a dyad could potentially be ‘too flexible’) or assess affective flexibility in the context of other task parameters (e.g. anxiety, goal orientation, and task completion) to more clearly delineate the adaptive aspects of dyadic affective flexibility. Finally, the participants were not culturally or socioeconomically diverse, and thus, generalizability of the findings across sociodemographic groups may be limited.

In summary, the present findings imply that maternal depressive symptoms in typical populations may limit dyadic flexibility in interactions with their children, which may relate to children’s burgeoning regulatory difficulties. Collectively, these relations put a spotlight on the importance of dyadic affective flexibility in early parent–child interactions. The examination of dynamic interaction patterns as markers of risk may be particularly important in early childhood, before these patterns stabilize and contribute to persistent developmental psychopathology in young children (Olson & Lunkenheimer, 2009). Finally, assessing early parent–child coregulatory processes in problem-solving situations, where the dyadic coregulation of affect and behaviour is required, may reveal potential mechanisms in the transmission of familial risk.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Corpuz R, Schwartz A. Preventing children’s aggression: Outcomes of an early intervention. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(5):1443–1449. doi: 10.1037/a0027303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Commentary: Conceptual and methodological challenges to the study of emotion regulation and psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32(1):92–95. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9169-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy M, Huang K, Lima J. Patterns of conflict interaction in mother–toddler dyads: Differences between depressed and non-depressed mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18(1):10–20. doi: 10.1007/s10826-008-9201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JF, Tronick EZ. Three-month-old infants’ reaction to simulated maternal depression. Child Development. 1983;54:185–193. doi: 10.2307/1129876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Teti LO, Zahn-Waxler C. Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen A, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(5):746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Downey G, Boergers J. Depression in families: A systems perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Developmental perspectives on depression. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1992. pp. 211–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35(1):73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(5):479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A. Mother–and father–child mutuality in Anglo and Indian British families: A link with lower externalizing problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:609–620. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000047210.81880.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Jennings K, Kelley SA, Marshal M. Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and toddlers’ behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(1):48–61. doi: 10.1080/15374410802575362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescence: Relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Development. 1995;66(1):139–151. doi: 10.2307/1131196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Duncan TE, Eddy JM, Fagot BI. The world of parents and peers: Coercive exchanges and children’s social adaptation. Social Development. 1994;3:255–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1994.tb00044.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Kavanagh KA. An experimental test of the coercion model: Linking theory, measurement, and intervention. In: McCord J, Tremblay R, McCord J, Tremblay R, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. pp. 253–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(1):50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Lemay P, Dauwalder J. Dynamic analyses of mother–child interactions in functional and dysfunctional dyads: A synergetic approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(4):317–329. doi: 10.1023/A:1010309929116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff E, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, Murphy BC. Mother’s emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76(5):1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, Mills RL, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Brownridge DA. Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment: The mediating role of parental behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(6):943–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor R, Roman G, Hart MJ, Hughes C. Mothers’ depressive symptoms and low mother–toddler mutuality both predict children’s maladjustment. Infant and Child Development. 2012;21:52–66. doi: 10.1002/icd.762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant–mother and infant–father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Developmental Psychobiology. 2007;49(3):290–302. doi: 10.1002/dev.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Garber J, Durlak JA. Current and past maternal depression, maternal interaction behaviors, and children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:527–537. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH. Depression in mothers. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106(3):458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth M, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Hollenstein T. Dynamic systems methods for models of developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:641–669. doi: 10.1017/S0954579403000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Lamey AV. Combining dynamic systems and multivariate analyses to compare the mother–child interactions of externalizing subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(3):265–283. doi: 10.1023/A:1015106913866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Patterson G. Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review. 2006;113:101–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, O’Hara A, Pepler D, Lewis M. A dynamic systems analysis of parent–child changes associated with successful “real-world” interventions for aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:845–857. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:742–751. doi: 10.1037/a0013514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrist AW, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Dyadic synchrony in mother–child interaction: Relation with children’s subsequent kindergarten adjustment. Family Relations. 1994;43:417–424. doi: 10.2307/585373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic KA, Baker JK. Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children’s emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science And Practice. 2006;6:271–295. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0604_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T. State space grids: Analyzing dynamics across development. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(4):384–396. doi: 10.1177/0165025407077765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Lewis MD. A state space analysis of emotion and flexibility in parent–child interactions. Emotion. 2006;6(4):656–662. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Granic I, Stoolmiller M, Snyder J. Rigidity in parent–child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):595–607. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000047209.37650.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabson JM, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, Burton J. The relationship process code v. 2.0. The University of Oregon Child and Family Center; 2004. Unpublished coding system. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson PB, Gelfand DM, Kulcsar E, Teti DM. Mother–toddler interaction patterns associated with maternal depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9(3):537–550. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, Bush NR. Temperament variation in sensitivity to parenting: Predicting changes in depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:1199–1212. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Knaack A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray K, Jacques TY, Koenig AL, Vandegeest K. Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child Development. 1996;67:490–507. doi: 10.2307/1131828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamey A, Hollenstein T, Lewis MD, Granic I. GridWare (version 1.1). [Computer software] 2004 http://statespacegrids.org.

- Leckman-Westin E, Cohen PR, Stueve A. Maternal depression and mother–child interaction patterns: Association with toddler problems and continuity of effects to late childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1176–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Lamey AV, Douglas L. A new dynamic systems method for the analysis of early socioemotional development. Developmental Science. 1999;2(4):457–475. doi: 10.1111/1467-7687.00090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy M. Maternal depression: Effects on social cognition and behavior in parent–child interactions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1991;19(6):693–706. doi: 10.1007/BF00918907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Dishion TJ. Developmental psychopathology: Maladaptive and adaptive attractors in children’s close relationships. In: Guastello S, Koopmans M, Pincus D, editors. Chaos and complexity: The theory of nonlinear dynamical systems. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Hollenstein T, Wang J, Shields AM. Flexibility and attractors in context: Family emotion socialization patterns and children’s emotion regulation in late childhood. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences. 2012;16:269–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Olson SL, Hollenstein T, Sameroff AJ, Winter C. Dyadic flexibility and positive affect in parent–child coregulation and the development of child behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(2):577–591. doi: 10.1017/S095457941100006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma I, Tamminen T, Kaukonen P, Laippala P, Puura K, Salmelin R, Almqvist F. Longitudinal study of maternal depressive symptoms and child well-being. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(12):1367–1374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200112000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize J, Pettit GS. Mothers’ social coaching, mother–child relationship style, and children’s peer competence: Is the medium the message? Child Development. 1997;68:312–332. doi: 10.2307/1131852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide: Fifth edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Lunkenheimer ES. Expanding concepts of self-regulation to social relationships: Transactional processes in the development of early behavioral adjustment. In: Sameroff AJ, editor. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ. Social risk and self-regulation problems in early childhood. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Lunkenheimer ES, Kerr DCR. Self-regulatory processes in the development of disruptive behavior problems: The preschool to school transition. In: Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, editors. Biopsychosocial regulatory processes in the development of behavior problems. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 144–185. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Bank L. Some amplifying mechanisms for pathologic processes in families. In: Gunnar MR, Thelen E, editors. Systems and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 167–209. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeGarmo D, Forgatch M. Systematic changes in families following prevention trials. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):621–633. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000047211.11826.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament and development. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JE, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in childhood. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 187–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. In: Horowitz FD, editor. Review of child development research. Vol. 4. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Shields AM, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(6):906–916. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Lewis M. Agreement among parents, teachers, and children on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:107–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ, Cohn JF. Infant–mother face-to-face interaction: Age and gender differences in coordination and the occurrence of miscoordination. Child Development. 1989;60:85–92. doi: 10.2307/1131074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick E, Reck C. Infants of depressed mothers. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):147–156. doi: 10.1080/10673220902899714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Beeghly M, Olson KL, Tronick EZ. Effects of maternal depression and panic disorder on mother–infant interactive behavior in the face-to-face still-face paradigm. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2008;29(5):472–491. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Beeghly M, Tronick EZ. Making up is hard to do, especially for mothers with high levels of depressive symptoms and their infant sons. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(7):670–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Iannotti RJ, Cummings E, Denham S. Antecedents of problem behaviors in children of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2(3):271–291. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400000778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]