Abstract

Background:

Medicare Part D and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) use different approaches to manage prescription drug benefits, with implications for spending. Medicare relies on private plans with distinct formularies, whereas the VA administers its own benefit using a national formulary.

Objective:

To compare overall and regional rates of brand-name drug use among older adults with diabetes in Medicare and the VA.

Design:

Retrospective cohort.

Setting:

Medicare and the VA, 2008.

Patients:

1 061 095 Medicare Part D beneficiaries and 510 485 veterans aged 65 years or older with diabetes.

Measurements:

Percentage of patients taking oral hypoglycemics, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) who filled brand-name drug prescriptions and percentage of patients taking long-acting insulins who filled analogue prescriptions. Sociodemographic- and health status–adjusted hospital referral region (HRR) brand-name drug use was compared, and changes in spending were calculated if use of brand-name drugs in 1 system mirrored the other.

Results:

Brand-name drug use in Medicare was 2 to 3 times that in the VA: 35.3% versus 12.7% for oral hypoglycemics, 50.7% versus 18.2% for statins, 42.5% versus 20.8% for ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and 75.1% versus 27.0% for insulin analogues. Adjusted HRR-level brand-name statin use ranged (from the 5th to 95th percentiles) from 41.0% to 58.3% in Medicare and 6.2% to 38.2% in the VA. For each drug group, the 95th-percentile HRR in the VA had lower brand-name drug use than the 5th-percentile HRR in Medicare. Medicare spending in this population would have been $1.4 billion less if brand-name drug use matched that of the VA.

Limitation:

This analysis cannot fully describe the factors underlying differences in brand-name drug use.

Conclusion:

Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes use 2 to 3 times more brand-name drugs than a comparable group within the VA, at substantial excess cost.

Primary Funding Source:

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Medicare’s Part D drug benefit provides drug coverage to nearly 30 million beneficiaries, at an annual cost of nearly $60 billion (1). Although Part D has lowered out-of-pocket costs (2) and improved treatment adherence (3-7) and health outcomes (8, 9), there is evidence of inefficiency. For example, per-capita prescription drug spending in Part D varies more than 2-fold across hospital referral regions (HRRs), with 75% of the difference due to variation in use of more expensive drugs (8). In principle, greater reliance on generic drugs in Medicare could save taxpayers substantially without compromising care. However, the mechanisms for achieving these savings and their potential magnitude are unknown. Looking to other systems that have achieved greater generic use may provide insight.

Medicare contracts with more than 1000 private plans to administer drug benefits, each using a distinct formulary and cost-sharing arrangement (9). Other public payers, such as the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), have taken a different approach. All veterans face the same low cost-sharing, and benefits are managed by a central pharmacy benefits manager with a single formulary. This national formulary has substantially lowered pharmacy spending for the VA (10), although studies suggest that facility-level variation persists in use of certain brand-name drugs (11, 12).

Comparing medication use and regional variation across these 2 national payers could shed light on ways to improve efficiency in Medicare Part D, at a time when the U.S. government is facing substantial budget pressures and seeking ways to reduce costs without undermining quality (13-15). Previous studies have focused on comparing medication prices between the VA and Medicare (16-18) but not medication choice, which can play just as large a role in determining spending. We constructed 2 national cohorts of older adults receiving drug benefits in either Medicare Part D or the VA with diabetes, a common chronic condition with high medication use and a wide range of available therapies (19). We compared use of brand-name medications among patients overall and by geographic region and estimated how spending would change if use of brand-name drugs in 1 system mirrored the other.

Methods

Data Sources and Sample

The Medicare cohort was defined using Medicare Denominator, Parts A and B, and Prescription Drug Event

Context

Comparing the use of brand-name and generic drugs among patients receiving benefits from Medicare Part D or the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) may help assess means of reducing costs.

Contribution

In this evaluation of outpatient prescriptions, the use of brand-name drugs for treating patients with diabetes was 2 to 3 times higher in Medicare Part D than in the VA, even after adjustment for regional variations in health status. If Medicare use of generic drugs had mirrored the VA during the study period, estimated savings would have been more than $1 billion.

Implication

Large savings may be seen with greater use of generic drugs among Medicare Part D beneficiaries.

—The Editors

files for a 40% random sample. We included beneficiaries who were alive and continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare and a stand-alone prescription drug plan in 2008, were aged 65 years or older, and had 2 or more inpatient or outpatient diagnoses for type 2 diabetes mellitus (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes 250.×0, 250.×2) or filled a prescription for an oral diabetes medication in 2008 (20). We excluded persons in Medicare Advantage plans because our data did not include all of their claims. We created an identically defined national cohort of veterans using 2008 national Medical SAS Datasets, VA data on outpatient prescriptions, and enrollment data. From both cohorts, we excluded persons whose home address could not be linked by ZIP code to a Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare HRR (21) and persons with evidence of lengthy institutionalization (either ± 90-day stay in a VA nursing home or receipt of ±25% of Part D prescriptions from a long-term care pharmacy).

Study Outcomes

We focused on 4 medication groups commonly used by patients with diabetes: oral hypoglycemics, long-acting insulin, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs). Oral prescriptions were categorized as brand-name or generic using LexiComp Multum (Lexi-Data Basic database, Cerner Multum, Denver, Colorado). Insulin used as basal coverage was deemed “long-acting” and categorized as “analogue” (such as glargine and detemir) or “nonanalogue” (such as neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin) to parallel cost differences for brand-name and generic oral medications (Appendix Table 1, available at www.annals.org) (22). In the VA during our study period, all brand-name drugs among these oral medications were nonformulary and available only with prior authorization (12); long-acting insulin analogues, however, were on the VA formulary with few restrictions.

For both cohorts, we measured the proportion of patients who filled at least 1 prescription for a brand-name medication (or insulin analogue) for each medication group. We also calculated the percentage of standardized 30-day prescriptions dispensed as brand for oral products and the percentage of units dispensed as analogues for insulin.

Patient Covariates

We used residential ZIP codes to assign patients to 1 of 306 HRRs, as others have done in previous analyses of geographic variation (8, 23, 24). To adjust estimates of brand-name drug use for patient differences across HRRs in each system, we identically constructed variables for age, sex, race (black, white, Hispanic, or other), the number of chronic conditions (excluding diabetes) (25), the number of diabetes complications (diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and diabetes-associated peripheral vascular disorder) (26), the number of unique oral diabetes medications, and the presence of serious mental illness (schizophrenia or schizoaffective and bipolar disorders, delusion and paranoid disorders, and other psychoses). We assigned annual household incomes based on ZIP code–level median incomes from a 2006 extrapolation of 2000 Census data (21, 27). To account for within-system differences in cost sharing, we created an indicator in Medicare for Part D low-income subsidy status and in the VA for persons with no prescription copayment.

Analysis

Analyses were done identically for Medicare and VA cohorts. We calculated the proportion of patients using any brand-name drug of interest (or insulin analogue) nationally. We obtained crude HRR-level rates of brand and analogue use and then estimated adjusted rates or probabilities for each HRR using multivariable logistic regression models, specifying weights for the coefficients across the classification effects proportional to those in the Medicare or VA population (Proc Genmod procedure, lsmeans/om). The model was performed at the patient level, including the covariates described and indicators for each HRR. We compared HRR-level brand-name drug use between Medicare and the VA using distributional dot plots. Because unadjusted and adjusted rates were nearly identical within each cohort (correlation r > 0.93), we present only adjusted rates.

We quantified the effect of differences in brand-name drug use on drug spending by comparing actual spending with estimated spending if Medicare and the VA were to adopt each other’s rate of brand or analogue use. To calculate actual spending, we first calculated the mean amount paid (“cost”) in 2008 for 30-day supplies of medications for brand-name and generic drugs separately. Medicare cost data included total reimbursements to the pharmacy (that is, plan payment, consumer copayment, and dispensing fee), whereas the VA pharmacy data included only ingredient costs; we added patient copayments and an average dispensing fee obtained from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service to the cost of each VA prescription. These additions to VA costs served to make Medicare and VA costs more comparable for descriptive purposes, but ultimately, we did not focus on these price differences in our analysis. We focused on the within-system change in spending if use of brand-name drugs changed while prices stayed the same. To remove the effect of price outliers, we set any cost per prescription less than the 1st percentile equal to the 1st percentile and any cost greater than the 99th percentile equal to the 99th percentile.

We calculated total spending for each oral medication group as follows: [(total prescriptions × percent brand-name × mean cost per brand-name prescription) + (total prescriptions × percent generic × mean cost per generic prescription)]. For insulin, we used a similar approach but calculated spending based on units dispensed and the mean cost for analogues and nonanalogues. To estimate the effect of only changing rates of brand-name use in Medicare and the VA, we held constant each system's volume and cost per prescription (or unit) while adopting the other system's rate of brand or analogue use. Total expenditures in Medicare were projected onto the entire stand-alone Part D population by multiplying spending for the 40% sample by 2.5.

We performed 2 sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated analyses limiting both samples to men. Second, to limit the possibility of overlap in prescription use in the VA and Medicare for those with dual coverage, we excluded veterans also enrolled in Medicare Part D (29%) and repeated our analysis; we also completed an analysis excluding veterans enrolled in Part D who had a Medicare physician visit in 2008 (11%), assuming that these persons would be more likely to fill a prescription through Part D. Finally, as an additional analysis, we examined separately the subgroup of prescriptions that are multisource drugs available in both brand-name and generic forms (in contrast to single-source drugs, which have no direct generic substitute). All analyses were done using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and Stata, version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the study design, conduct, and analysis or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Our sample included 1 061 095 Medicare Part D beneficiaries and 510 485 veterans with diabetes. Mean patient age was 74.6 years in Medicare and 75.0 years in the VA, and VA patients were predominately male (98.6%) (Table 1). Compared with the VA cohort, the Medicare cohort had a slightly higher proportion of patients with no comorbid conditions (52.4% vs. 48.9%) and no diabetes complications (82.1% vs. 75.8%) but also a higher proportion of patients with 3 or more comorbid conditions (10.6% vs. 6.7%). Although the proportion of each cohort using oral hypoglycemics and long-acting insulins was nearly identical, Medicare patients were less likely to use statins (63.0% vs. 75.5%) and ACE inhibitors or ARBs (69.1% vs. 73.1%) than were VA patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics*

| Characteristic | Overall |

Oral Hypoglycemics |

Long-Acting Insulin |

Statins |

ACE Inhibitors/ARBs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | |

| Patients, n (%) | 1 061 095 (100) | 510 485 (100) | 780 738 (73.6) | 377 435 (73.9) | 231 869 (21.9) | 113 736 (22.3) | 668 989 (63.0) | 385 196 (75.5) | 733 176 (69.1) | 373 321 (73.1) |

| Mean age (SD), y | 74.6 (6.9) | 75.0 (6.4) | 74.4 (6.8) | 74.8 (6.4) | 74.0 (6.7) | 74.0 (6.2) | 74.2 (6.6) | 74.8 (6.3) | 74.4 (6.8) | 74.7 (6.3) |

| Male, % | 38.1 | 98.6 | 38.7 | 98.7 | 36.0 | 98.7 | 38.6 | 98.7 | 37.1 | 98.7 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||||||

| White | 78.2 | 86.5 | 78.1 | 87.3 | 74.6 | 83.1 | 78.3 | 86.9 | 77.0 | 86.0 |

| Black | 12.1 | 10.3 | 11.5 | 9.6 | 16.1 | 13.5 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 12.9 | 10.8 |

| Hispanic | 3.8 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 1.0 |

| Other | 5.9 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 2.3 |

| Number of Charlson Comorbidity Index conditions, %† |

||||||||||

| 0 | 52.4 | 48.9 | 56.0 | 51.3 | 37.9 | 38.4 | 53.0 | 47.8 | 52.8 | 48.3 |

| 1−2 | 37.0 | 44.4 | 35.3 | 43.1 | 43.3 | 49.8 | 36.3 | 45.0 | 36.6 | 44.6 |

| ≥3 | 10.6 | 6.7 | 8.7 | 5.6 | 18.8 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 7.1 |

| Serious mental illness, %‡ | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Number of diabetes complications, % | ||||||||||

| 0 | 82.1 | 75.8 | 83.1 | 77.8 | 66.2 | 55.5 | 81.2 | 75.3 | 81.1 | 74.5 |

| 1−2 | 17.3 | 23.5 | 16.5 | 21.7 | 31.8 | 42.0 | 18.1 | 23.9 | 18.3 | 24.7 |

| ≥3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Number of oral diabetes medications, % | ||||||||||

| 0 | 26.4 | 26.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 41.9 | 40.7 | 22.8 | 11.0 | 23.1 | 11.1 |

| 1 | 43.9 | 45.4 | 59.7 | 61.5 | 34.4 | 37.3 | 44.1 | 53.3 | 44.2 | 52.4 |

| 2 | 22.9 | 24.5 | 31.2 | 33.1 | 18.0 | 19.0 | 25.1 | 30.4 | 25.0 | 31.1 |

| 3 | 6.0 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 5.1 |

| ≥4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Estimated annual household income, $§ | 50 863 | 50 007 | 50 821 | 49 826 | 49 062 | 48 762 | 51 425 | 50 122 | 50 708 | 49 790 |

| No or limited copayment, %∥ | 42.5 | 31.5 | 42.5 | 30.8 | 53.1 | 35.2 | 42.7 | 30.5 | 43.7 | 31.9 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” denotes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Excluding diabetes.

Defined by the presence of an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, code for schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, bipolar, delusion and paranoid disorders, and other nonorganic psychoses.

Based on ZIP code–level median incomes from a 2006 extrapolation of 2000 Census data.

In Part D, we measure the percentage of patients with a full year of low-income subsidy; in the VA, we measure the percentage without any copayment for the entire year.

Variation in Brand-Name Drug Use

In unadjusted analyses, Medicare beneficiaries taking oral hypoglycemics were nearly 3 times more likely to use a brand-name drug than VA patients (35.3% vs. 12.7%). Similarly, among those using long-acting insulins, 75.1% in Medicare used analogues compared with only 27.0% in the VA. Between-system differences in use of brand-name statins (50.7% vs. 18.2%) and ACE inhibitors or ARBs (42.5% vs. 20.8%) were of similar magnitude. These differences in brand-name drug use were nearly identical in sensitivity analyses focusing on men only and in analyses that excluded veterans dually enrolled in Medicare Part D from the VA cohort (Appendix Tables 2 to 4, available at www.annals.org).

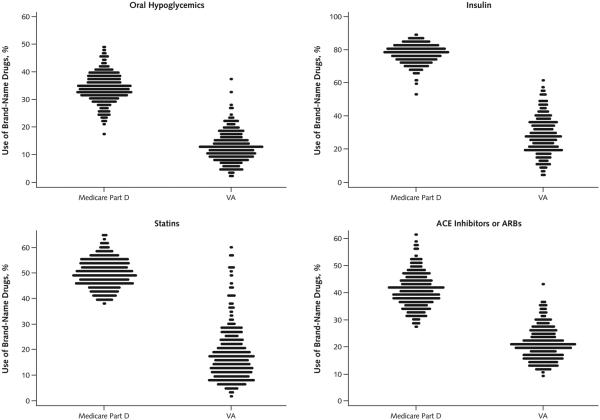

After adjustment for patient characteristics, brand-name drug use varied substantially by region within each of the 4 groups in both systems (Figure 1). In Medicare, the percentage using any brand-name oral hypoglycemics ranged from 25.1% in the 5th percentile to 42.4% in the 95th percentile of HRRs; in the VA, the range was 5.1% to 21.9%. Similarly, in Medicare, HRR-level use of any insulin analogues ranged from 68.3% to 85.4%, compared with 10.6% to 46.9% in the VA. Similar regional variation was evident for statins (range, 41.0% to 58.3% for Medicare and 6.2% to 38.2% for the VA) and ACE inhibitors or ARBs (range, 31.1% to 51.1% for Medicare and 12.7% to 31.0% for the VA) (Figure 1). In each group, the HRR at the 95th percentile of brand-name drug use in the VA was lower than the HRR at the 5th percentile in Medicare.

Figure 1. Distribution of adjusted HRR-level percentage of patients with diabetes aged 65 years or older in Medicare Part D and the VA using brand-name drugs (and insulin analogues).

Each dot is 1 HRR, and all HRR percentages are adjusted for sociodemographic and health status variables. “Statins” refers to 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; HRR = hospital referral region; VA = Veterans Affairs.

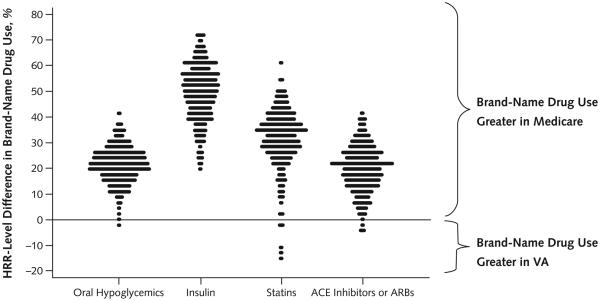

Use of brand-name drugs was greater in Medicare than in the VA in 298 of 306 HRRs, but these differences varied substantially (Figure 2). Most notably, in 3 HRRs the proportion of patients using brand-name statins was more than 10 percentage points higher in the VA than in Medicare. These outlier HRRs were geographically clustered in a small area of the country within 1 VA regional network.

Figure 2. Absolute difference, within each HRR, in adjusted percentage of patients with diabetes aged 65 years or older in Medicare Part D and the VA using brand-name drugs.

Each dot is 1 HRR, and all HRR percentages are adjusted for sociodemographic and health status variables. More positive differences indicate higher rates of brand-name use in Medicare compared with the VA in a given HRR. “Statins” refer to 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; HRR = hospital referral region; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Multisource Drugs

Use of multisource drugs was substantially higher in the VA than in Medicare (92.2% vs. 77.4% of all prescriptions for oral hypoglycemics, 89.8% vs. 54.7% for statins, and 80.2% vs. 64.9% for ACE inhibitors or ARBs) (Table 2). However, for the most common multisource drugs, prescriptions were dispensed primarily as generics in both Medicare and the VA.

Table 2.

Dispensed Multisource Prescriptions*

| Drug Classes and Select Multisource Drugs† | Prescriptions Filled for Multisource Medications, n (%) |

Multisource Medications Filled as Brand Name, % |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | |

| Oral hypoglycemic (overall) | 10 385 905 (100) | 5 098 778 (100) | – | – |

| Multisource hypoglycemics | 8 039 310 (77.4) | 4 701 283 (92.2) | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| Metformin | 3 858 287 (37.1) | 2 178 778 (42.7) | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| Glipizide | 1 761 020 (17.0) | 1 341 495 (26.3) | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Glyburide | 1 005 586 (9.7) | 1 105 382 (21.7) | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Statins (overall) | 6 095 802 (100) | 3 880 351 (100) | – | – |

| Multisource statins | 3 335 724 (54.7) | 3 483 255 (89.8) | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Simvastatin | 2 391 498 (39.2) | 3 152 515 (81.2) | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| Lovastatin | 526 221 (8.6) | 183 289 (4.7) | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| Pravastatin | 418 005 (6.9) | 147 451 (3.8) | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs (overall) | 7 274 793 (100) | 3 907 993 (100) | – | – |

| Multisource ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 4 724 142 (64.9) | 3 136 052 (80.2) | 4.2 | 0.3 |

| Lisinopril | 2 224 565 (30.6) | 2 493 730 (63.8) | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Enalapril | 531 402 (7.3) | 145 615 (3.7) | 0.5 | 0.08 |

| Lisinopril–hydrochlorothiazide | 354 640 (4.9) | 237 225 (6.1) | 0.4 | 0.1 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A, B, and stand-alone Part D.

The top 3 multisource drugs within Medicare are included for each class of oral medications. For statins, there were only 3 multisource drugs, which are listed. For ACE inhibitors/ARBs, benazepril–amlodipine was the third most commonly dispensed multisource drug but was not included for comparison because only 535 prescriptions were dispensed within the VA.

Spending Calculations With Changes in Brand-Name Drug Use

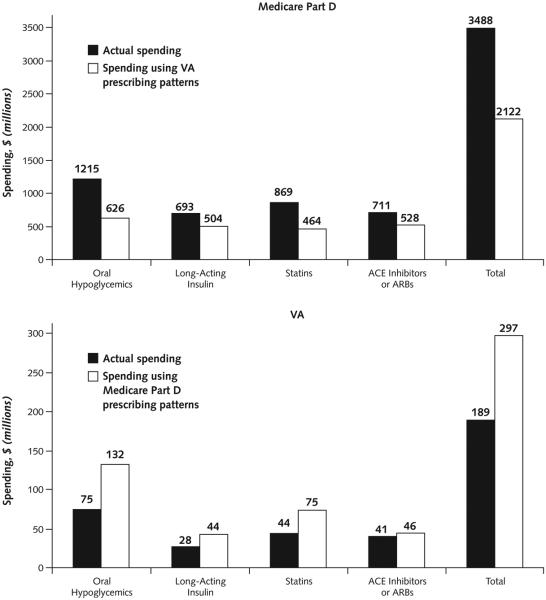

Table 3 shows the per capita volume of prescriptions filled among users in each medication group, which was slightly lower in Medicare than in the VA, whereas per capita drug costs were substantially higher. Across the 4 medication groups, spending in stand-alone Part D would have been $1.4 billion less (39%) in 2008 if brand-name drug use was similar to that of the VA, keeping volume and price unchanged (savings of $589 million for oral hypoglycemics, $189 million for insulin, $404 million for statins, and $183 million for ACE inhibitors or ARBs) (Figure 3). Conversely, spending in the VA (where prices are substantially lower) would have increased by $108 million (57%) if patients used brand-name drugs at the same rate as in Medicare.

Table 3.

Number of Dispensed Prescriptions, Percentage of Prescriptions Dispensed as Brand-Name, and Mean Cost Per Prescription*

| Variable | Oral Hypoglycemics |

Long-Acting Insulin† |

Statins |

ACE Inhibitors/ARBs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | Medicare | VA | |

| 30-d prescriptions or units, n | 10 385 905‡ | 5 098 778 | 2 875 278 349‡ | 1 978 168 710 | 6 095 802† | 3 880 351 | 7 274 793‡ | 3 907 993 |

| Mean prescriptions per patient per year, n |

13.3 | 13.5 | 12 400 | 17 393 | 9.1 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 10.5 |

| Prescriptions for brand-name drug, % |

23.3 | 7.4 | 60.6 | 16.8 | 45.5 | 12.3 | 37.8 | 20.0 |

| Mean cost per 30-d supply for brand-name drug, $§ |

156.2 | 79.6 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 100.6 | 32.5 | 74.3 | 16.2 |

| Mean cost per 30-d supply for generic drug, $§ |

13.6 | 9.6 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 20.7 | 8.5 | 17.7 | 9.1 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” denotes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors.

Values are based on the number of units dispensed rather than the number of prescriptions. Mean costs are costs per unit for analogue (“brand”) and nonanalogue (“generic”) insulin.

The number of prescriptions (insulin units) dispensed is for a 40% random sample Medicare denominator, and for our spending calculations, we multiplied by 2.5 to represent potential savings if applied to the entire fee-for-service Medicare Part D program.

Because VA costs typically include only ingredient costs and Medicare costs include total reimbursements to the pharmacy (i.e., plan payment, consumer copayment, and dispensing fee), we added patient copayments and an average dispensing fee to the cost of each VA prescription.

Figure 3. Prescription spending and projected spending if use of brand-name drugs would change, in each of 4 drug groups among diabetes patients aged 65 years or older in Medicare Part D and the VA in 2008.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” refers to 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

Discussion

Our analysis of more than 1 million Medicare Part D beneficiaries with diabetes and an identically defined cohort of older VA patients reveals stark differences in rates of brand-name medication use. Medicare beneficiaries are more than twice as likely to use brand-name drugs across 4 groups of commonly used medications. Had patterns of medication use in Medicare mirrored those of the VA for these medications in patients with diabetes alone, the program could have saved more than $1 billion in 2008. Yet, we saw similarly wide regional variation in brand-name drug use in both systems, suggesting that non–health system factors play major roles in such variation.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate the magnitude of difference in brand-name versus generic drug prescribing between Medicare and the VA among a comparable population. These findings point to opportunities for improving efficiency without harming quality of care or access to effective medicines. Although we cannot determine the optimal rate of brand-name drug use in either system, no evidence suggests that the differences we report reflect underuse of brand-name drugs in the VA (28-31). In fact, the VA provides a reasonable benchmark for use of generic drugs in Medicare because it performs as well or better than commercial health plans and Medicare on several measures of quality for diabetes and related conditions (28-31).

Furthermore, strong evidence shows similar effectiveness of generic versus brand-name drugs in the classes we studied (32-35). For example, generic and brand-name statins have been shown to be equally effective for clinical end points (33, 35). Any indication for a more potent, brand-name statin (for example, insufficient lipid lowering with generic statin) is unlikely to be substantially more prevalent in Medicare than in the VA. Similarly, although some clinicians recommend insulin analogues to individual patients rather than neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin because of lower rates of symptomatic nocturnal hypoglycemia, their overall effectiveness is similar (32), and differences in prevalence of nocturnal hypoglycemia alone are unlikely to explain why 3 of every 4 Medicare patients receiving insulin use analogues versus 1 of 4 VA patients.

One structural factor that may explain much of the between-system difference in brand-name drug use is the VA’s ability to promote “therapeutic substitution” by prescribers using a national formulary. Therapeutic substitution is the interchange by clinicians of generic drugs in the same class as, but not identical to, single-source, brand-name drugs (for example, generic simvastatin instead of brand atorvastatin (Lipitor [Pfizer, New York, New York]). This practice is distinct from mere “generic substitution,” in which brand and generic versions of the same drug are substituted (for example, switching simvastatin for Zocor [Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey]). Our analysis of multisource drugs suggests that the source of the different rates of brand-name drug use in the VA and Medicare is a difference in the use of single-source drugs, not in generic substitution among multisource drugs; generic substitution is, in fact, similar in the 2 systems. In addition to the VAS formulary, a national electronic medical record with electronic prescribing, limits on access by pharmaceutical sales representatives, and a salaried physician workforce may explain the lower rates of brand-name drug use in the VA.

Part D plans also have tools for encouraging use of less costly drugs (for example, placing brand-name drugs on high cost-sharing tiers, applying utilization management, or excluding drugs from the formulary), but they have applied them less extensively than has the VA. For example, in 2011 only 8%, 12%, and 61% of Part D enrollees faced step therapy requirements for atorvastatin, valsartan, and pioglitazone, respectively, and none faced prior authorization (36). In contrast, all VA enrollees faced step therapy and prior authorization requirements for these drugs. Part D plans may lack the incentives to apply these tools. In the current system, private Part D plans, which compete to enroll members, may lose market share if they restrict the use of widely used drugs and may also lose rebates on these drugs from pharmaceutical manufacturers (37).

Although a change in legislation to make Part D function like the VA may be neither politically feasible nor warranted, policy levers for increasing appropriate use of generic medications in Part D are available. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation is experimenting with pilot projects to increase efficiency in the Medicare program. Part D plans are currently rated and rewarded on the basis of measures of customer service, patient safety, and medication adherence (38). These existing pilot projects and incentive mechanisms could be used to reward greater efficiency as well.

Our analyses also demonstrate similarly wide regional variation in the use of brand-name drugs in both systems, even after adjustment for important differences in patient demographic characteristics and health status. The magnitude of the variation was similar between the 2 systems, which indicates that although the VA’s central formulary has reduced the average rate of brand-name drug use, it has not eliminated geographic variation. This may be due, in part, to the VA’s prior authorization policy, through which patients and their providers can request off-formulary, brand-name medications, a process that is adjudicated locally, not centrally. Local physician practice patterns, determined by complex yet poorly understood factors, including the supply of specialists, academic affiliations, social and professional physician networks, and prescription drug marketing, may also contribute to the geographic variation in brand-name drug use in both systems (39, 40).

Our study has several limitations. First, there may be unmeasured differences in the populations being compared. However, potential unmeasured differences across Medicare and the VA are unlikely to explain the large differences in brand-name drug use. Second, although some persons filled prescriptions in both Medicare and the VA, when we excluded dually enrolled veterans with Part D from our analysis, our results did not change. Third, we cannot estimate the effect of discount pharmacies offering $4 generics on our findings because in both the VA and Medicare, some persons could purchase $4 generics for cash without generating an insurance claim (41, 42). Fourth, we may overestimate potential savings because some of the brand-name drugs in our analysis have lost patent protection since our study year (2008); however, similar patterns of brand-name drug use probably exist among other drug groups. Fifth, we cannot account for rebates negotiated with manufacturers by Medicare plans, which are not publicly available. Incorporating rebates in our analyses could reduce Medicare brand-name drug spending by as much as approximately 19% based on 1 analysis (37); nonetheless, the magnitude of our savings estimate would still be more than $1 billion. Sixth, we estimate savings associated with changing only use of brand-name drugs, holding prices constant in each system. Estimates of cost savings for Medicare would be larger if it were feasible to obtain VA prices, although the government is forbidden from negotiating drug prices for the Medicare program (17, 18). Finally, our analyses assume no behavioral response by the pharmaceutical industry, which, when faced with lower sales in Medicare, may change its pricing or other marketing strategies, nor do we account for any potential indirect costs associated with brand-name drug use (for example, lower adherence) (43-45).

In conclusion, we found large differences in rates of brand-name drug use among patients with diabetes in Medicare Part D and the VA, with substantial economic implications. These differences likely reflect structural differences in formulary management between the 2 systems. For 4 medication groups alone, we estimated more than $1 billion of potentially avoidable spending on brand-name drugs in 2008 in Medicare Part D. Of importance, our findings draw on actual rates of generic drug use in an existing high-performing, high-quality health system and demonstrate what should be attainable in Medicare. These potential savings could be realized through policies that promote Part D plan efficiency and by encouraging physicians to consider costs and value in their prescribing (14, 46-50).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Hal Sox, MD, for his comments on a previous draft of the manuscript.

Grant Support: Dr. Gellad was supported by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development (CDA 09-207 and LIP 72-057) and Veterans Affairs Competitive Pilot Project Fund (XVA 72-156). Drs. Gellad and Donohue were jointly supported by the RAND–University of Pittsburgh Health Institute and the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 RR024153). Dr. Donohue was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS017695). Dr. Morden and Mr. Smith were supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (P01 AG019783 “Causes and Consequences of Health Care Efficiency”) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Dartmouth Atlas (Project 059491).

Appendix Table 1.

Included Drug Groups Used by Patients

| Drug Group and Included Classes* |

| Oral hypoglycemics |

| Biguanides |

| Sulfonylureas |

| Nonsulfonylurea insulin secretagogues (Nateglinide, Repaglinide) |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors |

| Thiazolidinediones |

| DPP-4 inhibitors |

| Long-acting insulin† |

| NPH |

| NPH–regular mix |

| Aspart protamine/Aspart mix‡ |

| Lispro protamine/Lispro mix‡ |

| Detemir (Levemir)‡ |

| Glargine (Lantus)‡ |

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) |

| All statins |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs |

| All ACE inhibitors and ARBs |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; DPP-4 = dipeptidyl peptidase-4; HMG-CoA = 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A; NPH = neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Includes combination products for each drug group (e.g., glyburide–metformin).

Used for basal insulin coverage, either once or twice daily.

Insulin analogues.

Appendix Table 2.

Sensitivity Analysis Focusing on Men Only*

| Patients Using Brand-Name Drug | Oral Hypoglycemics, % | Insulin Analogues, % | Statins, % | ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA original cohort | 12.7 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 20.8 |

| VA men only (sensitivity population) | 12.7 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 20.7 |

| Medicare original cohort | 35.3 | 75.1 | 50.7 | 42.5 |

| Medicare men only (sensitivity population) | 36.4 | 78.0 | 50.9 | 37.3 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” denotes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. A total of 656 753 Medicare beneficiaries (61.9%) and 6957 veterans (1.4%) were excluded.

Appendix Table 3.

Sensitivity Analysis Excluding All Persons Enrolled in Medicare Part D From the VA Cohort*

| Patients Using Brand-Name Drug | Oral Hypoglycemics, % | Insulin Analogues, % | Statins, % | ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients excluded | 28.3 | 29.4 | 28.0 | 27.8 |

| VA original cohort | 12.7 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 20.8 |

| VA nondual user (sensitivity population) | 12.8 | 26.5 | 18.3 | 20.8 |

| VA dual users (excluded population) | 12.4 | 28.5 | 18.1 | 20.8 |

| Medicare cohort | 35.3 | 75.1 | 50.7 | 42.5 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” denotes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. A total of 148 624 veterans (29% of the original VA cohort) were excluded.

Appendix Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis Excluding All Persons Enrolled in Medicare Part D and With a Medicare Physician Office Visit From the VA Cohort*

| Patients Using Brand-Name Drug | Oral Hypoglycemics, % | Insulin Analogues, % | Statins, % | ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients excluded | 10.8 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 10.2 |

| VA original cohort | 12.7 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 20.8 |

| VA nondual user (sensitivity population) | 12.8 | 26.3 | 18.3 | 20.6 |

| VA dual users (excluded population) | 11.8 | 33.0 | 17.8 | 22.1 |

| Medicare cohort | 35.3 | 75.1 | 50.7 | 42.5 |

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; VA = Veterans Affairs.

“Medicare” refers to patients enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A and B and stand-alone Part D. “Statins” denotes 3-hydroxy-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. A total of 57 314 veterans (11% of the original VA cohort) were excluded.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article represents the opinions of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M12-3073.

Current Author Addresses: Drs. Gellad, Zhao, Mor, Good, and Fine: Veterans Affairs Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, 7180 Highland Drive, Pittsburgh, PA 15206.

Dr. Donohue: Department of Health Policy and Management, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 130 DeSoto Street, Crabtree Hall A613, Pittsburgh, PA 15261.

Dr. Thorpe: University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 919 Salk Hall, 3501 Terrace Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261.

Mr. Smith and Dr. Morden: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, 35 Centerra Parkway, Lebanon, NH 03766.

References

- 1.Congressional Budget Office Effects of Using Generic Drugs on Medicare’s Prescription Drug Spending. 2010 Sep; Accessed at www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/118xx/doc11838/09-15-prescriptiondrugs.pdf on 1 April 2012.

- 2.Polinski JM, Kilabuk E, Schneeweiss S, Brennan T, Shrank WH. Changes in drug use and out-of-pocket costs associated with Medicare Part D implementation: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1764–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03025.x. [PMID: 20863336] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donohue JM, Zhang Y, Lave JR, Gellad WF, Men A, Perera S, et al. The Medicare drug benefit (Part D) and treatment of heart failure in older adults. Am Heart J. 2010;160:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.023. [PMID: 20598987] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Lave JR, Gellad WF. The impact of Medicare Part D on medication treatment of hypertension. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:185–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01183.x. [PMID: 20880045] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madden JM, Graves AJ, Zhang F, Adams AS, Briesacher BA, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence and spending on basic needs following implementation of Medicare Part D. JAMA. 2008;299:1922–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1922. [PMID: 18430911] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donohue JM, Zhang Y, Aiju M, Perera S, Lave JR, Hanlon JT, et al. Impact of Medicare Part D on antidepressant treatment, medication choice, and adherence among older adults with depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:989–97. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182051a9b. [PMID: 22123272] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polinski JM, Donohue JM, Kilabuk E, Shrank WH. Medicare Part D’s effect on the under- and overuse of medications: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1922–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03537.x. [PMID: 21806563] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue JM, Morden NE, Gellad WF, Bynum JP, Zhou W, Hanlon JT, et al. Sources of regional variation in Medicare Part D drug spending. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:530–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1104816. [PMID: 22316446] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Fact Sheet. 2009 Mar; Accessed at www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-09.pdf on 1 April 2012.

- 10.Huskamp HA, Epstein AM, Blumenthal D. The impact of a national prescription drug formulary on prices, market share, and spending: lessons for Medicare? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:149–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.149. [PMID: 12757279] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gellad W, Mor M, Zhao X, Donohue J, Good C. Variation in use of high-cost diabetes mellitus medications in the VA healthcare system [Letter] Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1608–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4482. [PMID: 23044980] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gellad WF, Good CB, Lowe JC, Donohue JM. Variation in prescription use and spending for lipid-lowering and diabetes medications in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:741–50. [PMID: 20964470] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antos JR, Pauly MV, Wilensky GR. Bending the cost curve through market-based incentives. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:954–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1207996. [PMID: 22852881] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307:1513–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.362. [PMID: 22419800] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel E, Tanden N, Altman S, Armstrong S, Berwick D, de Brantes F, et al. A systemic approach to containing health care spending. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:949–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1205901. [PMID: 22852883] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson GA, Panangala SV, Hearne J. Pharmaceutical Costs: A Comparison of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Medicaid, and Medicare Policies. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; Washington, DC: Jan 17, 2007. Accessed at http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/RL33802_20070117.pdf on 1 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Feldman R. Should Medicare adopt the Veterans Health Administration formulary? Health Econ. 2012;21:485–95. doi: 10.1002/hec.1733. [PMID: 21506191] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellad WF, Schneeweiss S, Brawarsky P, Lipsitz S, Haas JS. What if the federal government negotiated pharmaceutical prices for seniors? An estimate of national savings. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1435–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0689-7. [PMID: 18581187] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander GC, Sehgal NL, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. National trends in treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, 1994-2007. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2088–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2088. [PMID: 18955637] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 2):B10–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [PMID: 15113777] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Accessed at www.dartmouthatlas.org on 1 April 2012.

- 22.Drugs for type 2 diabetes Treatment Guidelines from The Medical Letter. 2011;9:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Baicker K, Newhouse JP. Geographic variation in the quality of prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1985–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010220. [PMID: 21047217] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Steinman MA, Kaplan CM. Geographic variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1465–71. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3717. [PMID: 23007171] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [PMID: 1607900] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:15–23. [PMID: 18197741] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Census Bureau American FactFinder. Accessed at http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml on 1 April 2013.

- 28.Trivedi AN, Matula S, Miake-Lye I, Glassman PA, Shekelle P, Asch S. Systematic review: comparison of the quality of medical care in Veterans Affairs and non-Veterans Affairs settings. Med Care. 2011;49:76–88. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f53575. [PMID: 20966778] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, Selby JV, Piette JD, Curb JD, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [PMID: 15313743] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2218–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [PMID: 12773650] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, Hayward RA, Shekelle P, Rubenstein L, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [PMID: 15611491] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, Ebrahim SH, Gratzer TW, Plank J, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005613. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005613.pub3. [PMID: 17443605] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, Stedman MR, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.758. [PMID: 19050195] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Orlando LA, Patel MR, Patel UD, Patwardhan MB, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for treating essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:16–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00189. [PMID: 17984484] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green JB, Ross JS, Jackevicius CA, Shah ND, Krumholz HM. When choosing statin therapy: the case for generics. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:229–32. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1529. [PMID: 23303273] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Analysis of Medicare Prescription Drug Plans in 2011 and Key Trends Since 2006. 2011 Sep; Accessed at www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8237.pdf on 1 April 2012.

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General Higher Rebates for Brand-Name Drugs Result in Lower Costs for Medicaid Compared to Medicare Part D. 2011 Aug; Accessed at https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-10-00320.pdf on 1 May 2012.

- 38.Hargrave E, Hoadley J, Summer L, Merrell K. Toward Meaningful Quality and Performance Measures in Part D. Report to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2010 May 28; Accessed at www.medpac.gov/documents/Oct10_PartDQualityandPerformanceMeasuresPartD_CONTRACTOR_RS.pdf on 1 May 2012.

- 39.Barnett ML, Christakis NA, O’Malley J, Onnela JP, Keating NL, Landon BE. Physician patient-sharing networks and the cost and intensity of care in US hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50:152–60. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822dcef7. [PMID: 22249922] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kronick R, Gilmer TP. Medicare and Medicaid spending variations are strongly linked within hospital regions but not at overall state level. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:948–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1065. [PMID: 22566433] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH. Four-dollar generics—increased accessibility, impaired quality assurance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1885–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006189. [PMID: 21067379] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Gellad WF, Zhou L, Lin YJ, Lave JR. Access to and use of $4 generic programs in Medicare. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1251–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1993-9. [PMID: 22311333] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298:61–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [PMID: 17609491] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, Glassman PA, Nair K, DeLapp D, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:332–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.332. [PMID: 16476874] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank RG, Newhouse JP. Should drug prices be negotiated under part D of Medicare? And if so, how? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:33–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.33. [PMID: 18180478] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabow P, Halvorson G, Kaplan G. Marshaling leadership for high-value health care: an Institute of Medicine discussion paper. JAMA. 2012;308:239–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7081. [PMID: 22669121] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laine C. High-value testing begins with a few simple questions [Editorial] Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:162–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00016. [PMID: 22250151] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith CD; Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine–American College of Physicians High Value Teaching high-value, cost-conscious care to residents: the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine–American College of Physicians Curriculum. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:284–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00496. [PMID: 22777503] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilt TJ, Qaseem A. Implementing high-value, cost-conscious diabetes mellitus care through the use of low-cost medications and less-intensive glycemic control target. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1610–1. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.203. [PMID: 23044715] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [PMID: 22492759] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]