Abstract

Zoonoses involve infections and infestations transmissible from animals to humans. Zoonoses are a major global threat. Exposure to zoonotic pathogens exists in various settings including encroachment on nature; foreign travel; pet keeping; bushmeat consumption; attendance at zoological parks, petting zoos, school ‘animal contact experiences’, wildlife markets, circuses, and domesticated and exotic animal farms. Under-ascertainment is believed to be common and the frequency of some zoonotic disease appears to be increasing. Zoonoses include direct, indirect and aerosolized transmission. Improved awareness of zoonoses in the hospital environment may be important to the growing need for prevention and control. We reviewed relevant literature for the years 2000 to present and identified a significant need for the promotion of awareness and management of zoonoses in the hospital environment. This article provides a new decision-tree, as well as staff and patient guidance on the prevention and control of zoonoses associated with hospitals.

Introduction

The frequency of some zoonotic disease appears to be increasing, although the overall prevalence of zoonoses in general as well as in the hospital environment is unknown. However, the risk of zoonotic pandemics has been acknowledged as a major global threat to human health.1 Hospitals are often an early portal for infection cases and must be equipped to promptly and effectively diagnose and control the spread of zoonotic disease. Hospital staff who are not aware of or have not implemented appropriate disease prevention and control measures may incidentally facilitate the spread of zoonotic pathogens.

Under-ascertainment is believed to be common because numerous zoonoses superficially resemble common illnesses such as gastrointestinal, respiratory and dermal disease and thus may go undiagnosed. Monitoring is also highly incomplete.2 Furthermore, despite increasing governmental and nongovernmental efforts at prevention and control, public adherence to cautionary guidance has not resolved epidemiological occurrence or expansion, and frequency of some zoonotic disease appears to be increasing.3 For example, in the United States in the 1960s, pet turtle-related salmonellosis was found to be responsible for approximately 14% of all Salmonella infections (approximately 280,000 cases annually) and despite massive public education aimed at prevention, the epidemic did not abate until the trade and keeping of small turtles was banned in 1975, which resulted in a 77% reduction in disease by the following year.4 According to region and animal keeping dynamics, reptile-related salmonellosis (RRS) may nowadays be responsible for between 1 and 18% of all human Salmonella infections. In the United Kingdom, for example, RRS may account for 1–5% of all salmonelloses, and between 1160 and 6000 cases of disease annually.5,6

Around 200 zoonoses are known, of which at least 70 are associated with captive wild animals including exotic pets.7 Sixty-one percent of human diseases are considered to be of zoonotic origin8 and 75% of global emerging human disease has a link to wild animals.9 Exotic pets in particular present a highly diverse and potentially potent reservoir of infection and infestation. Several authors have described the exotic pet trade as a Trojan horse of human disease based on the unsuspecting invitation of pathogens into the home via animals perceived to be harmless.7 Zoonoses include direct, indirect and aerosolized transmission. Improved awareness of zoonoses in the hospital environment may be important to the growing need for prevention and control.

Hospitals themselves may even unknowingly transfer zoonotic pathogens to patients, as was evidenced during a donor transplantation in 2005. Following organ transplants from a single donor to four patients in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, all four recipients were found to have been infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). This rodent-borne arenavirus had apparently been contracted by the donor from an infected pet hamster.10 More recently, in the US, a patient died after acquiring rabies following a kidney transplant.11 Whilst transplant-related zoonoses are relatively rare, new guidelines are in place to reduce transplant associated diseases.12 RRS has also been acquired via platelet transfusion from a donor who kept a pet snake.13

Zoonoses can also be transmitted to hospital personnel, as was the case in Mauritania in 2003, following the admission of a patient who had contracted Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever from a goat. This disease was transmitted within the hospital to 15 people and resulted in the infection and death of five hospital workers.14 A report in 1998 described an outbreak of Malassezia pachydermatis involving 15 infants that was introduced into the intensive care nursery on health care workers’ hands and which originated from domestic pet dogs, and thence was spread via patient-to-patient transmission.15

Certain injuries are capable of resulting in topical, local and systemic infection with a wide variety of zoonotic pathogens, and there are many opportunities for injuries with zoonotic implications to occur.16,17 Domestic and exotic pets are responsible for a small, but possibly increasing, annual number of injuries, envenomations and stings.16–19 For example, in the UK, NHS Health Episode Statistics for England indicate that between 2004 and 2010, there were 28,605 full hospital consultation episodes, 28,149 admissions and 59,511 hospital bed days associated with injuries probably related to dogs. During the same period, 760 full hospital consultation episodes, 709 admissions and 2121 hospital bed days were associated with injuries probably related to exotic pets.17 These data represent a conservative list of possible sources and thus may not include all similar episodes. In Australia, 2001–2002 hospitalization statistics attributed 12,688 episodes to zoonotic and other bacterial diseases.20 In France and Germany, studies of all admissions for bites and stings from exotic pets at four poisons centres between 1996 and 2006 indicate 404 (mostly snake, fish and invertebrate) envenomation cases.19 Also, these data do not include primary care consultation episodes. Therefore, thorough wound cleansing and consideration for antimicrobial therapy are important in all incidents.16,17 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1985 (CDC’s) Study21 examined efficacy of nosocomial control and reported that hospitals with an epidemiologist, an infection control practitioner for every 250 beds, active surveillance mechanisms, and ongoing control efforts reduced nosocomial infection rates by approximately a third.

The present article presents an expanded protocol and strategy to aid the prevention and control of zoonotic nosocomials as well as providing guidance for dissemination to patients by hospital healthcare workers.

Methods

Relevant literature was identified through a search of the online databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Google Scholar and the Royal Society of Medicine) using the following terms: ‘zoonos’, ‘hospital’, ‘nosocomial’, ‘animal’, ‘pet’, ‘zoo’, ‘circus’, ‘farm’, ‘infection’, ‘infestation,’ ‘review’, ‘management’ and ‘pandemic’ for the years 2000 to present. Forty-five publications of prima facie relevance were identified and reviewed, of which 11 cogent articles and seven reports were identified. Of these publications, six successfully conformed to the essential inclusion criteria of being peer-reviewed as well as referring to hospitals and zoonoses in addition to the authors’ own libraries, although none of these publications were systematic reviews involving hospitals.

Results

Zoonoses prevention and control guidance relevant to hospitals appear to be generally under-represented, although some protocols and strategies have been published.21–23 Some recommended pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis regimens have been also described in order to reduce the incidence of both public and nosocomial disease, where zoonotic infections might be transmitted in a hospital environment.2,7,17,21,24,25

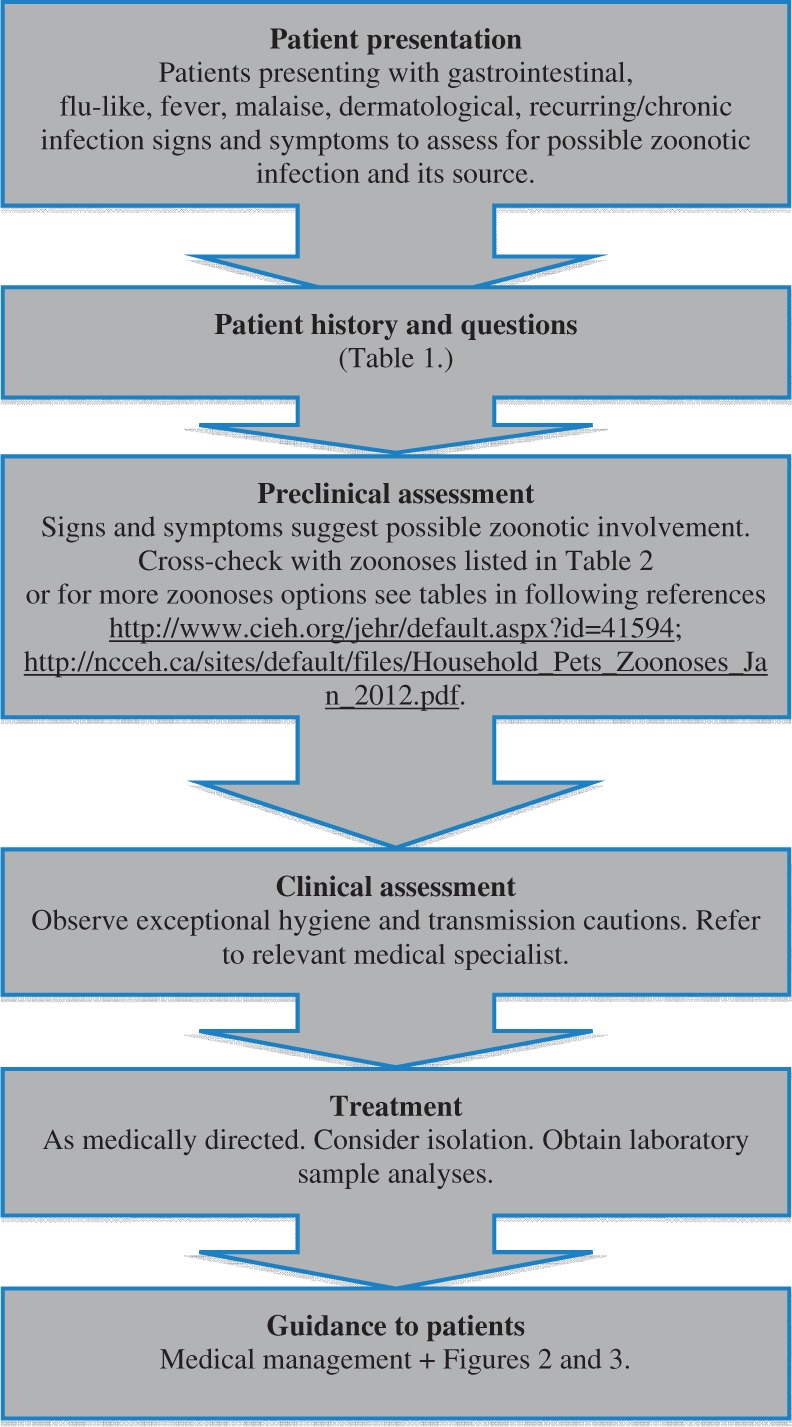

Assessing patients for zoonoses in the general hospital environment reflects regular patient management, with altered emphasis towards dedicated questions and history-taking. Signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal, flu-like, fever, malaise or dermatological nature often indicate possible zoonotic infection. Questions to patients should seek to establish possible direct or indirect exposure to animals or unusual animal products, which may indicate the source of a relevant disease. Figure 1 provides a simple management tree for assessment of patients for possible zoonoses.

Figure 1.

Zoonoses management tree.

Patient presentation

Patients presenting with signs and symptoms of acute onset, intermittent recurring or persistent disease, as well as those reporting conditions with a history of recurrence or of being difficult to treat should be regarded as red flag indicators. Examples include meningitis, gastrointestinal disorders, influenza-like disorders, dermatitis, fever, haemorrhagic fever and chronic inflammatory signs, for example, atypical arthroses, persistent low-grade fever.

Patient history and questions

Questions directed at patient history are essential to discovering possible zoonoses and their source. Given that many zoonoses are contagious, awareness and careful history-taking may assist to prevent or limit epidemiological outbreaks. Table 1 provides a list of questions dedicated to exploring possible zoonotic disease and their source associations. Positive responses to questions in Table 1 should also be regarded as red flag indicators.

Table 1.

Questions to ask patients presenting with gastrointestinal, flu-like, fever, malaise, dermatological signs and symptoms to assess for possible zoonotic infection and its source.

| Question to patient? |

|---|

| a) patient recently consumed exotic foods (e.g. sushi/seafood, turtle meat, bushmeat) |

| b) patient recently experienced foreign travel (e.g. fishing trip, eco-tour, adventure) |

| c) patient recently visited a foreign hospital |

| d) patient recently visited a farm |

| e) patient recently visited a zoo or other wildlife centre |

| f) patient recently visited a pet shop |

| g) patient household possesses any pets (especially exotic species) |

| h) patient recently visited a household that possesses pets (especially exotic species) |

| i) patient’s school recently held animal contact event |

| j) patient or others in the household may have recently experienced direct or indirect contact with persons or inanimate material from above categories |

Preclinical assessment

Patient history, signs and symptoms suggesting possible common zoonotic involvement can be cross-checked with information in Table 2. (Table 2 may also act as a general awareness chart for staff in a supportive health and safety context.) Patient history, signs and symptoms suggesting possible rare zoonotic involvement can be cross-checked with information in two recent, detailed, and highly accessible sources of both common and rare zoonoses, pathogens and their animal associations.7,24

Table 2.

Common zoonoses signs and symptoms.

| Zoonosis/condition | Source | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Salmonellosis/gastroenteritis | Fish, amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and pain, fever, painful joints, meningitis, flu-like |

| E. coli infection/gastroenteritis | Amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and pain, fever, painful joints, meningitis, flu-like |

| Campylobacteriosis/ gastroenteritis | Amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal-primate | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps and pain, fever, painful joints, meningitis, flu-like |

| Leptospirosis | Amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal | Flu-like, vomiting, icterus, telangiectasia, uveitis, splenomegaly, meningitis |

| Psittacosis | Bird, mammal-primate | Flu-like, pneumonia, fever, cough |

| Vibriosis | Fish, amphibian, reptile, bird | Gastrointestinal, pain, vomiting, fever, otitis |

| Lyme disease/bartonellosis | Mammal | Flu-like, fever, rash, gastrointestinal |

| Toxocariasis | Mammal | Eye problems |

| Giardiasis | Mammal-primate | Gastrointestinal, fever, nausea, fatigue, weight loss |

| Tuberculosis | Fish, amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal-primate | Respiratory, flu-like, fever, weight loss |

| Q-fever | Reptile, bird, mammal | Fever, flu-like |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Fish, amphibian, reptile, bird | Acute gastrointestinal disturbance, nausea, vomiting, pain, fever, flu-like |

| Macroparasite infestation, e.g. helminths and ectoparasites | Fish, amphibian, reptile, bird, mammal, mammal-primate | Gastrointestinal disturbance, abdominal cramps and pain, weight loss, flu-like |

| Ringworm | Mammal, mammal-primate | Patchy skin, inflammation, itching |

| Allergic alveolitis | Bird | Persistent dry cough, chest irritation |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) | Mammal | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fever, headache, fatigue. |

If experiencing these indicators report to a healthcare professional. These are a small sample of relatively common animal-to-human diseases (derived with permission from Warwick et al.,7 http://www.cieh.org/jehr/default.aspx?id = 41594). Onset of signs and symptoms of an animal-related disease may occur within hours or not for several weeks or months following exposure to an exotic animal. Most cases of diseases are not serious, but it is important to report any suspicion of having an animal-linked disease because treatment may vary from regular illnesses and early access to medical help can alleviate greater problems as well as assist health workers to provide best advice.

Although domesticated animals, for example dogs and cats, are frequent carriers of zoonotic agents in the home, most veterinarians and doctors are aware of certain common zoonoses (for example, scabies, ringworm, hydatidiosis, toxocariasis, bartonellosis). Therefore, regular medics may quickly recognize many risks and advise accordingly. However, veterinarians encounter exotic pets (which harbour more diverse and novel pathogens) less frequently. Therefore, zoonotic disease may go unrecognized or misdiagnosed due to low familiarity. Relatedly, exotic agents are frequently more persistent and severe than those from domestic animals.7

Clinical assessment

Clinical assessment should wherever possible include laboratory microbial investigation. Many zoonotic pathogens may be highly resistant to typical therapies, and pathogen identification is thus a key component for successful diagnosis and treatment. General staff can successfully manage many zoonoses whereas others require specialist medical knowledge and referral.

Treatment

Proper diagnosis and treatment are importantly matched with frequent follow-up consultation and also often psychological support is valuable. Presence of parasites, for example, can result in apprehension and serious mental stress, and some rational explanation of the relative normality of host-parasite relationship can be moderately comforting for some patients. Numerous zoonotic episodes may present as acute onset and emergency conditions, and further constitute potential epidemic proportions. Accordingly, important suspected or confirmed cases should be reported to relevant surveillance authorities in the interests of disease prevention and control.26 Acquired information should include patient age, sex, geographical status, occupation, clinical symptoms, date of onset, exposure to animal (species if known), microbiological and serological data and treatment.23

Zoonotic risk is complex, involving both rare and common problems, and ranges from the low probability of severe danger, for which there is no prevention and cure (for example, Herpesvirus-B from some primates), to hazards that are widespread and either self-limiting or potentially serious and with varied treatment success (for example, Salmonella from reptiles), through to moderate threats that are routinely controlled (for example, worms from dogs).7,21,27

Guidance to hospitals

When patients are admitted for the diagnosis and treatment of suspected serious zoonoses such as haemorrhagic fevers, there is a high risk of a disastrous nosocomial spread of infection. To avoid such outbreaks, it is critical that infection control measures are undertaken. For serious zoonotic diseases that have high person-to-person transmission potential, both pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis regimens have been described by the Centers for Disease Control.21,27 Pre-exposure regimens may include the vaccination of hospital staff for diseases such as rabies and monkeypox. Post-exposure regimens may include such measures as patient isolation, protective barrier nursing techniques, safe disposal of materials and body wastes and staff health monitoring.21,27

Guidance to patients

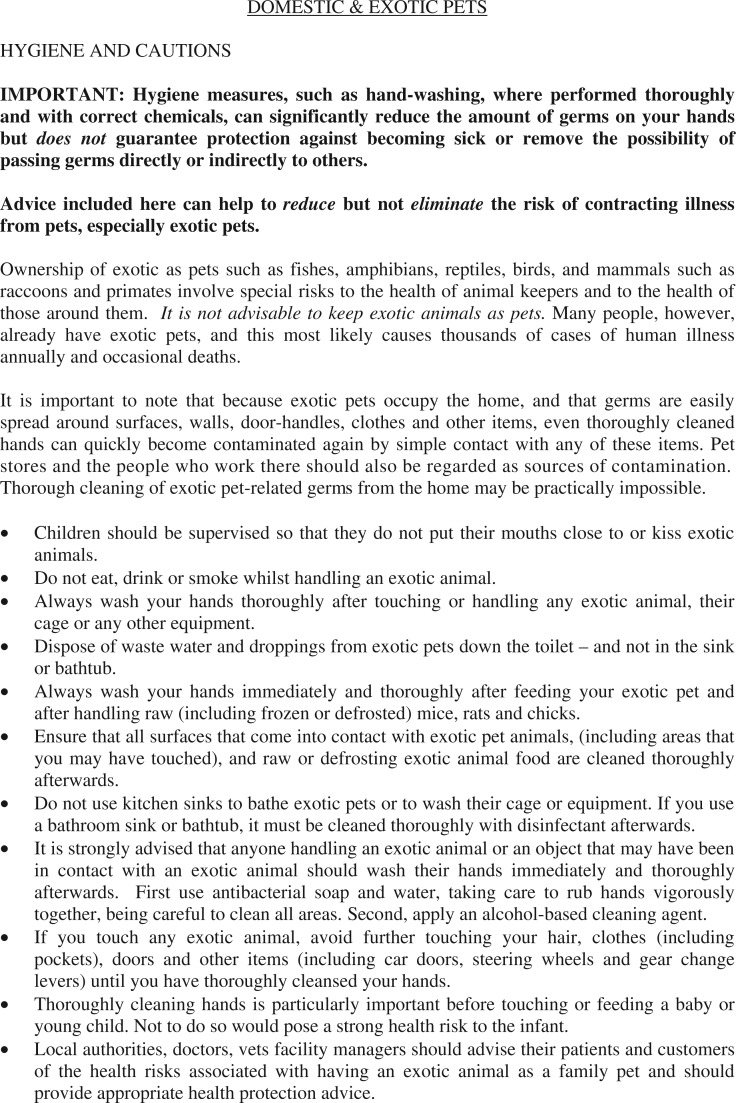

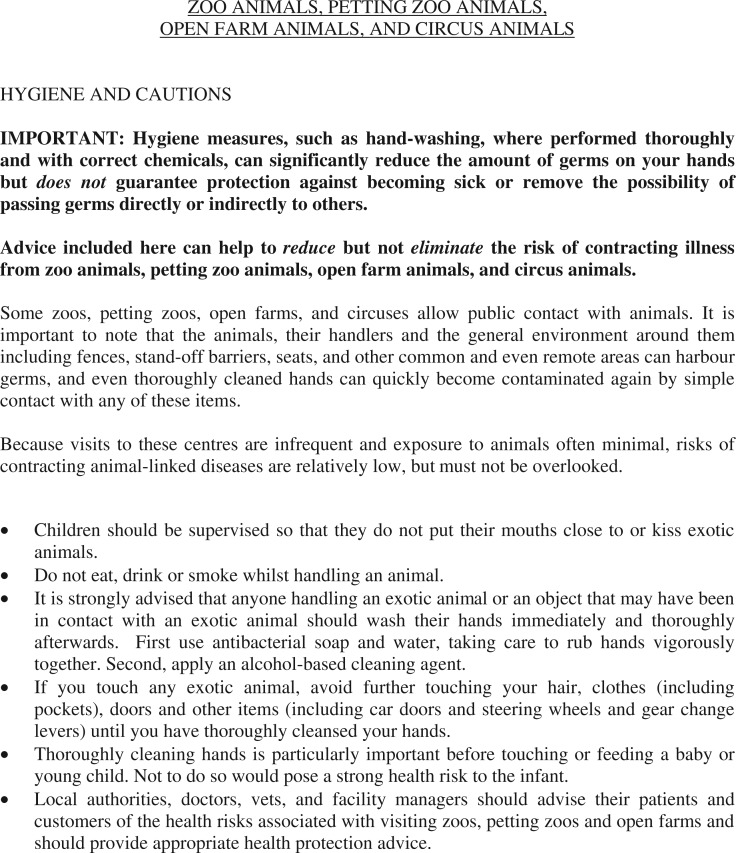

Where some possible zoonotic exposure may be suspected, Figures 2 and 3 provide user-friendly evidence-based guidance on zoonoses prevention and control, allowing clear information that can be handed to patients by hospital staff. Patients should be advised that animals may be symptomatic or asymptomatic carriers of pathogens, thus the animal’s condition may not itself indicate risk of transmission.

Figure 2.

Avoiding animal-linked disease associated with pets (derived with permission from Warwick et al.,7 http://www.cieh.org/jehr/default.aspx?id = 41594).

Figure 3.

Avoiding animal-linked disease associated with zoos, petting zoos, open farms, and circuses (derived from Warwick et al.,7 http://www.cieh.org/jehr/default.aspx?id = 41594).

Discussion

The dearth of literature pertaining to zoonoses in the hospital environment, whether regarding patient presentation or nosocomial outbreaks, is unfortunate and probably reflects a historical lack of awareness towards this type of disease and its monitoring. Under-ascertainment of zoonoses is also encountered in the primary care setting, which implies that there is a fundamental deficiency in healthcare management that could result in sick patients failing to receive appropriate medical treatment, failure to recognize pending epidemic outbreaks and incidental promotion of nosocomial disease.

Education of hospital staff at the ‘grass-roots’ level is probably a major prerequisite of adequate patient treatment as well as the prevention and control of zoonoses. In order for such education to be effective, hospital staff must familiarize themselves with essential exploratory protocols to identify relevant management areas as well as the red-flag signs and symptoms of patients. Accordingly, we have considerably focused on producing dedicated guidance for awareness that is directed both at the healthcare professional, and at the public who present with suspected zoonoses.

Zoonotic pathogens frequently originate from remote world regions and thus involve opportunities for highly novel pathogens to exploit immunologically naïve people. As frequent accommodators of diversely immunocompromised persons, hospitals possess the potential to become epidemic hubs. Improved management of these risks appears to demand a holistic approach that must include administration, medicine and generalized education.

Conclusions

Zoonoses are significant and increasingly emerging diseases for which hospital staff should maintain continuous patient- and self-centred awareness. Some zoonoses respond well to conventional treatments whether incidentally or following proper diagnosis. However, some will not respond favourably, whether or not properly diagnosed, and long persist. Accordingly, it is important for general hospital medical staff to inform respective secondary care specialists of zoonotic suspicions to facilitate early investigation, as this may be highly important to outcome. Although not widely considered, zoonoses potentially present a novel and possibly increasing source of nosocomial infection and infestation. For this reason, in cases of suspected serious zoonoses, the risk of nosocomial outbreaks should be managed by hospitals through an established regimen of both pre-exposure and post-exposure infection control measures. In addition, there is a dearth of data regarding prevalence of zoonoses in the hospital environment, and this deficiency may be improved by greater general awareness of the issue by all secondary care staff.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This study was conducted unfunded by both the Emergent Disease Foundation and Collaborating for Global Health.

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

CW

Contributorship

All authors contributed equally

Provenance

This article was submitted by the authors and peer reviewed by Ray Greek

References

- 1. Morse SS, Mazet JAK, Woolhouse M, et al. Prediction and prevention of the next pandemic zoonosis. Lancet 2012; 380: 1956–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Warwick C. Gastrointestinal disorders: are healthcare professionals missing zoonotic causes? J R Soc Health 2004; 124: 137–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abbott SL, Ni FCY, Janda MJ. Increase in extraintestinal infections caused by Salmonella enterica subspecies II–IV. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18: 637–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mermin J, Hutwagner L, Vugia D, et al. Reptiles, amphibians, and human salmonella infection: a population-based, case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 253–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aiken AM, Lane C, Adak GK. Risk of Salmonella infection with exposure to reptiles in England, 2004–2007. EuroSurveillance 2010; 15: 19581–19581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Toland E, Warwick C, Arena PC. The exotic pet trade: pet hate. Biologist 2012; 59: 14–18 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Warwick C, Arena PC, Steedman C, Jessop M. A review of captive exotic animal-linked zoonoses. J Environ Health Res 2012;12:9–24. See http://www.cieh.org/jehr/default.aspx?id=41594 (last checked 8 February 2013)

- 8. Karesh WB, Cook RA, Gilbert M, Newcomb J. Implications of wildlife trade on the movement of avian influenza and other infectious diseases. J Wildl Dis 2007; 43: 55–9 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown C. Emerging zoonoses and pathogens of public health significance – an overview. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot 2004; 23: 435–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anonymous. Centers for disease control and prevention. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in organ transplant recipients – Massachusetts, Rhode Island, 2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:537–9. See http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15931158 (last checked 8 February 2013) [PubMed]

- 11. Dishneau D. Transplant Guidelines Too Late for Rabies Victim. Associated Press, 2013. See http://www.nbcnews.com/id/51317629/ns/health/t/transplant-guidelines-too-late-rabies-victim/#.UXEM6I7iOQI (last checked 19 April 2013)

- 12. OPTN. Guidance for Reporting Potential Deceased and Living Donor-Derived Disease Transmission Events (PDTE). Maryland, USA: Organ Transplant Procurement Center, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. See http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/SharedContentDocuments/PDDTE_Exhibit_B_Guidance.pdf (last checked 19 April 2013)

- 13. Jafari M, Forsberg J, Gilcher RO, et al. Salmonella sepsis caused by a platelet transfusion from a donor with a pet snake. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1075–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nabeth P, Cheikh DO, Lo B, Faye O, Vall IO, Niang M, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Mauritania. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:2143–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1012.040535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Chang HJ, Miller HL, Watkins N, et al. An epidemic of Malassezia pachydermatis in an intensive care nursery associated with colonization of health care workers’ pet dogs. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 706–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldstein EJ. Bite wounds and infection. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14: 633–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warwick C, Steedman C. Injuries, envenomations and stings from exotic pets. J R Soc Med 2012; 105: 296–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. deHaro L, Pommier P. Envenomation: a real risk of keeping exotic house pets. Vet Hum Toxicol 2003; 45: 214–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schaper A, Desel H, Ebbecke M, et al. Bites and stings by exotic pets in Europe: an 11 year analysis of 404 cases from Northeastern Germany and Southeastern France. Clin Toxicol 2009; 47: 39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anonymous Australian Hospital Data, Australia: AIHW, 2001–2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weber T, Rutala W. Risks and prevention of nosocomial transmission of rare zoonotic diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:446–56. See http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/3/446.full (last checked 8 February 2013) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. CVM. Protocol for Handling Patients with Zoonotic Infections. See http://www.cvm.ncsu.edu/vhc/idm/la25-patients-with-zoonotic-infections.php (last checked 8 February 2013)

- 23. Narayan KG. Zoonoses: challenges and strategies. Indian J Public Health 2000; 44: 44–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith A, Whitfield Y. Household pets and zoonoses. National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health, 2012, p.33. See http://ncceh.ca/sites/default/files/Household_Pets_Zoonoses_Jan_2012.pdf (last checked 8 February 2013)

- 25. Warwick C, Arena PC, Steedman C. Visitor behaviour and public health implications associated with exotic pet markets: an observational study. J R Soc Med Short Rep 2012; 3: 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO. Recommended Standards and Strategies for Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases. World Health Organization, 2012. See http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub04/surveillancestandards_en.pdf (last checked 8 February 2013)

- 27. Garner JS. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996; 17: 53–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]