Abstract

Korea has adopted Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officers through the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) since 1999 for systematic control of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Graduates of medical schools in Korea are selected and serve as public health doctors (PHDs) for their mandatory military service. The duration of service is 3 years and PHDs comprise general practitioners and specialists. Some PHDs are selected as EIS officers with 3 weeks basic FETP training and work for central and provincial public health authorities to conduct epidemiological investigations. The total number of EIS officers is 31 as of 2012. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) has 12 specialists, whereas specialists and each province has one or two EIS officers to administer local epidemiological investigations in 253 public health centers. The Korean EIS officers have successfully responded and prevented infectious diseases, but there is a unique limitation: the number of PHDs in Korea is decreasing and PHDs are not allowed to stay outside Korea, which makes it difficult to cope with overseas infectious diseases. Furthermore, after 3 years service, they quit and their experiences are not accumulated. KCDC has hired full-time EIS officers since 2012 to overcome this limitation.

Keywords: epidemiological investigation, Epidemic Intelligence Service, Field Epidemiology Training Program, public health doctor

1. Introduction

Korea has designated notifying infectious diseases and controlled infectious diseases since 1954, and the division of disease control in the Korea National Institute of Health (KNIH) conducted epidemiological investigation on infectious diseases until the introduction of Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officers in 1999. In major epidemics, joint investigation was conducted with experts in the civil sector. Control was for epidemics only and no epidemiological investigators were available except in central government, therefore, control and surveillance of infectious diseases had limitations [1]. The existing control system has reached its capacity since the 1980s with massive outbreaks of water and food-borne diseases and emergence/outbreaks of various infectious diseases such as leptospirosis, legionella, Vibrio vulnificus septicemia, scrub typhus, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, anthrax, and tularemia. Epidemiological investigations on shigellosis were not routinely conducted, with the exception of some outbreaks, which is a huge limitation in establishing disease control policy. Furthermore, there has been a re-emergence and consistent increase in incidence of vivax malaria since 1993, after elimination in 1978, and it has not been systematically investigated [2].

In the late 1990s, the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) was developed to cope with emerging/re-emerging infectious diseases, and Japan, Thailand, and the Philippines have developed such programs. Korea introduced EIS officers and FETP as a pilot program in 1999 for systematic investigation and control of infectious diseases [1]. EIS officers and FETP became regular features in 2000, and Korea Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention (KCDC) was launched in 2004 and the EIS division is responsible for epidemiological investigation.

2. History, System, and Programs of EIS

2.1. History of EIS officers

In 1999, KNIH selected 19 EIS officers in a pilot program. The officers comprised existing public health officials and public health doctors (PHDs) who were supposed to take mandatory military service based on the “Special Act for Public Health and Medicine in Rural Areas” [3]. They took a 2-week FETP and were dispatched to KNIH and 16 provincial public health authorities, and were involved in epidemiological investigations and research. The pilot program of EIS officers has been successfully established with relative ease of securing qualified experts. The regular EIS and FETP program began in 2000. With a revision of the Communicable Disease Act on January 12, 2000 in which epidemiological investigations were specified, the EIS officers conducted an active investigation with support of the legal system [4]. The EIS officers take 3 weeks basic training and go through two sessions of on-the-job training. About 30 EIS officers are available each year. 2012 saw the 14th graduation of FETP/EIS officers, and a total of 213 graduates have worked as EIS officers. Most of the PHDs appointed to the EIS officers are specialists who have finished resident training courses. The specialties of EIS officers are varied: internal medicine forms the largest proportion, followed by pediatrics, family medicine, preventive medicine, and neurology (Table 1).

Table 1.

EIS officers' specialties (unit: persons) 1999–2012

| Location | Specialty | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Internal medicine | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 14 | |||||||

| Pediatrics | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 15 | |||||

| Family medicine | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||

| Preventive medicine | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Neurology | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Occupational and Environmental medicine | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Other specialty∗ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 53 | |

| Provincial | Internal medicine | 4 | 4 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 89 | |

| Pediatrics | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 13 | ||||||||

| Family medicine | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Preventive medicine | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Neurology | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Other specialty† | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 17 | |||||

| General practitioner | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 12 | |||||||||

| No information | 7 | 7 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Subtotal | 14 | 15 | 7 | 18 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 160 | |

| Total | 18 | 19 | 10 | 23 | 13 | 14 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 11 | 19 | 9 | 13 | 213 |

EIS = Epidemic Intelligence Service.

Other specialty in Central Government: laboratory medicine 1, urology 1, obstetrics and gynecology 1, pathology 1.

Other specialty in provincial government: anesthesiology 1, urology 4, obstetrics and gynecology 2, thoracic surgery 2, radiology 2, orthopedics 1, rehabilitation medicine 1, surgery 1, ear, nose and throat 1, dermatology 1, ophthalmology 1.

2.2. System of EIS

Every Korean man undergoes mandatory military service, and doctors serve as military doctors or PHDs to fulfill their duties. Each year EIS officers are selected from PHDs and public health officials for epidemiological investigation, but PHDs are the major source for EIS officers. All EIS officers from PHDs are men, because only men have military duty in Korea. The duration of duty for PHDs is 3 years, and they are composed of general practitioners and specialists. PHDs that are selected as EIS officers undergo 3 weeks basic FETP and are allocated to KCDC and 16 provinces. After 2 years service, EIS officers can work as FETP fellows for 1 year on a voluntary basis. The total number of PHD EIS officers (∼30 persons) is maintained by replacing the retiring EIS officers with new ones.

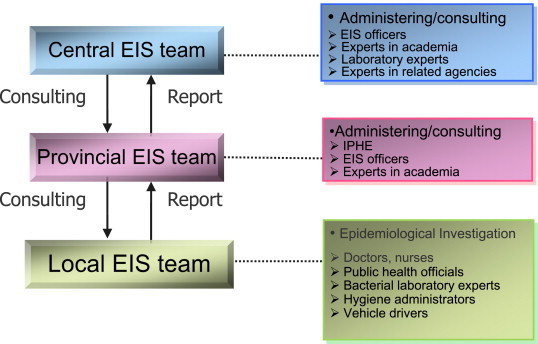

Until 2012, PHD EIS officers in specialties related to infectious diseases and epidemiology were randomly selected and allocated to KCDC by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which is the authority for allocating PHDs. PHD EIS officers allocated to provinces are randomly selected from among all PHDs in the provinces. In 2012, 31 EIS officers were on duty; 12 of whom were in KCDC and 19 were in 16 provinces. The provincial EIS officers administer epidemiological investigations in the provinces and 253 local public health centers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

System of epidemiological investigation in Korea.

In 2012, the EIS officer program was revised to secure the services of experts: KCDC hired two senior researchers that are required to serve a minimum 5 years of epidemiological investigation. The random selection procedure of the Ministry of Health and Welfare was changed, and KCDC can select the PHDs on a voluntary basis.

2.3. Education and training programs of EIS

The education and training of EIS officers aims to foster expertise in field epidemiology by giving intensive programs on epidemiological investigation and disease control. This expert pool serves to construct and fortify the nationwide network of infectious disease experts, and provides international collaboration. EIS officers should complete a 3-week basic program and attend 70% of on-the-job training opportunities twice yearly. They are also required to give at least one oral presentation in scientific conferences or publish a minimum of one paper in epidemiological journals.

The basic course aims to acquire field response capacities through providing basic knowledge and techniques on epidemiology and infectious disease control. The basic course includes epidemiology, biostatistics, national control system of infectious diseases, surveillance system, epidemic investigation, response to bioterrorism, and computing. The duration is 3 weeks, but it is flexible: 2 weeks in 1999, 4 weeks in 2000–2008, 1 week in the 2009 influenza pandemic, and 3 weeks in 2010–2012. There are a total of 83 hours and the course is held in either April or May. The first week is an introductory and includes methodology of investigation and national control systems of infectious diseases. In the second week, details are discussed about epidemiological investigation according to the type of infectious disease and type of outbreak. The final week is the exercise week for specimen collection, risk communication, and group discussion. Two examinations are given to evaluate achievement and an average score of 60% is required to complete the course. Instructors are professors, EIS officers, and public health officials [5,6].

On-the-job training is to acquire an in-depth knowledge about infectious diseases and the methodology of epidemiological investigation. Discussion of cases allows the participants to share their experiences and information. It has been held four times a year up to 2009, and reduced to twice yearly since 2010. The duration is 15 hours each time and it is held in September and November.

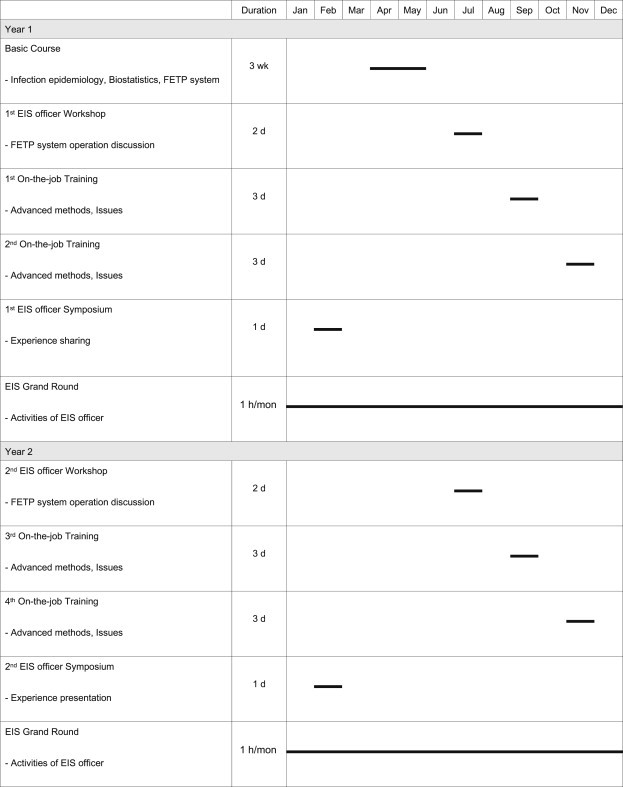

Two days extracurricular activity are held in July each year to discuss how to improve the EIS officer program, and the EIS scientific conference is held in February to present the results of investigations and to update related information. In KCDC, the EIS Grand Round is held each month to summarize and study the public health issue of that month (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

FETP courses in Korea. EIS = Epidemic Intelligence Service; FETP = Field Epidemiology Training Program.

3. Job Description and Achievements of EIS Officers

EIS officers conduct epidemical investigation or give advice when an outbreak of an infectious disease occurs in their vicinity, in collaboration with local public health authorities. EIS officers are involved in epidemiological investigation of cases or outbreaks of eliminated diseases such as measles, along with case investigations of imported diseases. They also investigate cases and outbreaks of adverse reactions to immunization. They monitor the trends in the notifiable infectious diseases, with consistent surveillance and epidemiological analysis, and conduct additional investigations and epidemiological analysis if necessary. They publish the results of their investigations and analysis in journals and present them at scientific conferences. They are also responsible for training local public health officials who conduct epidemiological investigations. Their major achievements are summarized in Table 2 [7–19].

Table 2.

Major achievements of EIS officers, 1999–2012 (unit: persons)

| Year | Disease | Region | Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Measles | National | Outbreak (32,647) |

| 2001 | Cholera | Goseong | Outbreak (18) |

| 2003 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome | National | Suspected cases |

| 2004 | Hepatitis A virus | Gongju | Outbreak (105) |

| 2005 | Avian influenza virus | National | High risk group |

| 2006 | Shigellosis | Sancheong | Outbreak (198) |

| 2007 | Falciparum malaria | Busan | Confirmed case |

| Human monkey pox | Seoul | Suspected case | |

| 2008 | Norovirus | Churwon | Outbreak (625) |

| 2009 | Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) | National | Outbreak (>100,000) |

| Hepatitis A virus | Seoul | Outbreak (33) | |

| 2010 | Hepatitis A virus | Inje | Outbreak (44) |

| 2011 | Humidifier disinfectant lung injury | National | Outbreak (>100) |

| 2012 | Pertussis | Yeongam | Outbreak (154) |

| Lyme disease | Hwacheon | Confirmed case |

EIS = Epidemic Intelligence Service.

4. Discussion

The US established EIS officers in 1951 to detect early, and cope with, outbreaks of infectious diseases and bioterrorism, and they currently extend to cover chronic diseases and injuries. The US EIS programs consist of 4-week basic courses with field exercises and four additional courses in the following 2 years. Japan started an FETP and produced five graduates in 1999, focusing on the epidemiological investigation of infectious diseases. After taking a 1-month basic course with theory and practice, the officers are put into field investigation. The European Union has the European Programme for Intervention Epidemiology Training (EPIET) in which the medical doctors, nurses, microbiologists, veterinarians, epidemiologists, and public-health-related experts of 26 countries participate. EPIET has a 3-week basic course and field training, and four or five 1-week modules for 2 years. Germany has a 2-year Postgraduate Training for Applied Epidemiology, which is run closely with EPIET and most applicants are medical doctors. The 29 graduate from 1995 to 2006 have worked as EIS officers [20]. Korea has similar 3-week basic training courses and four sessions of on-the-job training with other FETP trainees, but the Korean EIS officers take different tracks after completion of FETP. Most Korean graduates work in the clinical field, whereas most FETP graduates go the public health route (Table 3). This difference might be explained by motivation: the Korean FETP is part of the mandatory military service for male doctors, so specialists can be recruited with a relatively low salary, but they have a corresponding low interest in public health. After their period of duty, they return to their clinical fields.

Table 3.

Careers of EIS officers after mandatory service (information available persons only)

| Career type | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician | 47 | 46.5 |

| Professor | 49 | 47.5 |

| Public health official | 5 | 5.0 |

EIS = Epidemic Intelligence Service.

The Korean EIS/FETP is unique in that it can draw highly qualified specialists, but it has clear limitations. First, the number of PHDs is decreasing and it is hard to secure EIS officers [21]. This is related to the change in the Korean medical school system, and the proportion of men is decreasing in medical schools. Korea introduced a graduate medical school in 2005. Those leaving after 6 years at medical school with 2 years pre-medical and 4 years medical major training has changed. After they achieve a bachelor's degree, they can apply to the graduate medical school for a 4-year course. Most male students admitted to the graduate medical schools have already fulfilled their military duties, and the proportion of female students has increased rapidly. As a result, the number of PHDs is sharply decreasing, so it is difficult to secure EIS applicants. Second, efficiency and continuity of work decreases. After 3 years completion of FETP, new EIS officers replace the graduates and need time to become accustomed to the new environment. This has a negative long-term effect on the project or research. Third, the PHDs' official status is as an army officer, so they have restrictions on staying overseas. This hinders international travel and activity of EIS officers [22,23]. Considering the recent trends in most imported emerging/re-emerging infectious diseases, this travel limitation should be cleared for effective international collaboration in epidemiological investigation and infectious disease control. Fourth, PHDs' experiences and knowledge are not smoothly progressed. Few of them work for KCDC, and most of them practice in the community or return to the university hospitals. Some EIS graduates in university hospitals work together with KCDC for research and consultation, but most EIS graduates have no further relationship with KCDC.

To overcome these limitations, requires a lot of effort from KCDC. One of the most important changes has been for KCDC to select its own EIS official from 2012. Their status is as central government officials. These KCDC EIS officials are expected to complement current PHD EIS officers and to fill the vacuum caused by the lack of PHDs to some extent. KCDC EIS officials play a key role in long-term projects and research, and education of new EIS officers, and can actively cope with the international surveillance of infectious diseases. However, utilization of previous EIS officers' experiences and knowledge is still limited, because they have no obligation and it is hard to draw any motivation from them. Current EIS officers and officials have a strong bond with previous graduates. They invite previous EIS officers as lecturers and consultants at scientific conferences and for education programs.

Despite these limitations, Korea's EIS officer program is considered to be one of the major achievements of KCDC. Korea has seen various emerging/re-emerging infectious diseases since the introduction of the EIS officer program, and these officers have contributed to the control and prevention of the infectious diseases as epidemiological investigation experts. Korea's EIS program is a basis for successful disease control in Korea but it still has room for improvement.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2004. Basic courses of Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korea National Institute of Health . Korea National Institute of Health; Seoul: 1999. Cases of the Central Epidemiological Investigation Team. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health and Social Affairs . Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; Seoul: 1999. Special Act for Public Health and Medicine in Rural Area. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health and Social Affairs . Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; Seoul: 1999. Communicable Disease Prevention Act. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Osong: 2012. Basic courses of Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Osong: 2013. Basic courses of Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korea National Institute of Health . Korea National Institute of Health; Seoul: 2000. Cases of the Central Epidemiological Investigation Team. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korea National Institute of Health . Korea National Institute of Health; Seoul: 2001. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2003. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2004. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2004. White Paper on Disease Control. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2006. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2007. White Paper on Disease Control. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2008. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2009. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2010. White Paper on Disease Control. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Osong: 2011. Report of Epidemiological Investigation on Infectious Diseases. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2012. White Paper on Disease Control. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon S., Gwack J., Hwang K.J. Autochthonous lyme borreliosis in humans and ticks in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2013 Feb;4(1):52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dongkuk University . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Osong: 2011. Development of educational course and training manual for field epidemiologist training program during 2011–2015. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2010. Study on Effective Field Epidemiologist Training Program. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health and Welfare . Ministry of Health and Welfare; Seoul: 2011. Guideline to run public health doctors. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health and Welfare . Ministry of Health and Welfare; Seoul: 2013. Guideline to run public health doctors. [Google Scholar]