Abstract

During development and tissue homeostasis, patterns of cellular organization, proliferation, and movement are highly choreographed. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) play a critical role in establishing these patterns. Individual cells and tissues exhibit tight spatial control of the RTKs that they express, enabling tissue morphogenesis and function while preventing unwarranted cell division and migration that can contribute to tumorigenesis. Indeed, RTKs are deregulated in most human cancers and are a major focus of targeted therapeutics. A growing appreciation of the critical role of spatial RTK regulation during development prompts the realization that spatial deregulation of RTKs likely contributes broadly to cancer development and may impact the sensitivity and resistance of cancer to pharmacologic RTK inhibitors.

Members of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family of growth factor receptors control many fundamental cell behaviors (Box 1). The importance of these receptors in controlling cell decision-making is underscored by the prevalence with which they are causally implicated in cancer1. RTKs are under tight control by several modes of regulation, the best-studied of which are production – both transcriptional and post-transcriptional – and ligand availability. As such, aberrant RTK activation in cancer is often caused by gene amplification, receptor overexpression, autocrine activation, or gain-of-function mutations. However, mounting evidence suggests that RTKs are also subject to exquisite spatial control, in both individual cells and multicellular tissues. Indeed, RTKs first appeared evolutionarily during the transition to multicellularity as cells developed more complex and compartmentalized ways of interfacing with their environment2, 3.

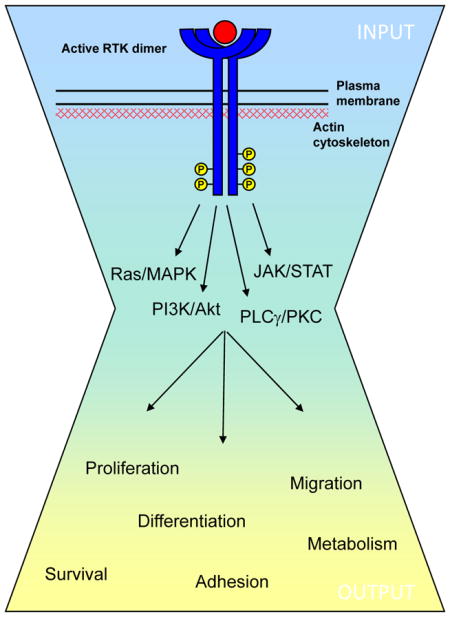

Box 1. Receptor tyrosine kinases.

The mammalian receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) superfamily of transmembrane receptors includes at least 58 members that share a conserved architecture (reviewed in Refs. #1,6). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was the first RTK discovered and the first found to be directly mutated in human cancer130. As such it has served as the prototype for understanding RTKs. Early studies led to the canonical view that EGFR and other RTKs are activated via ligand-induced dimerization, kinase activation and trans-phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain, creating docking sites for phosphotyrosine-binding effectors that initiate intracellular signaling cascades (see the Figure). It is generally thought that the broad array of signaling input to RTKs converges on a relatively small number of intracellular cascades. However, the signaling output can vary widely, depending upon the temporal and spatial activation of RTKs.

The interest in therapeutically targeting EGFR and other members of the ErbB family in cancer has prompted renewed investigation into how these RTKs are activated and pharmacologically inhibited. For example, structural and other studies have suggested more sophisticated mechanisms of ErbB partnering, activation and ligand-independent clustering8, 10, 12, 13, 131–133. Translational studies have yielded detailed and often unexpected insight into how pharmacologic inhibitors impact ErbB activity (reviewed in Refs. #134,135). Developmental studies have revealed complex patterns of EGFR activity that drive tissue morphogenesis61, 136, and molecular and systems-based studies have identified the importance of signal branching, feedback and phosphatase-mediated control in propagating and tuning the ligand-initiated response137, 138. These studies have advanced our understanding of ErbB signaling, but have also revealed gaps in our knowledge. Moreover, this ‘circumstantially-driven’ focus on ErbB receptors may have obscured the importance of other RTKs; for example, the discoidin domain receptors, which regulate the interactions of cells with their surrounding collagen matrix139, and the Ephs, which are activated by membrane-bound ligands on adjacent cells, and are members of the largest and evolutionarily most rapidly expanding RTK subfamily36.

While it was originally assumed that the ligand-induced activation of a given RTK could occur indiscriminately throughout the plasma membrane, it is now appreciated that receptors are neither uniformly distributed nor uniformly activated across the cell cortex4. The past two decades of research have revealed that the plasma membrane is highly and dynamically compartmentalized and suggested that this partitioning (lateral spatial control) plays a critical role in controlling RTK signaling. Moreover, RTK signaling is not limited to the cell surface, but can continue from within the endocytic compartment (axial spatial control). In fact, specific endocytic pathways can direct RTKs to subcellular compartments from which they can activate distinct intracellular pathways. Importantly, at both the cell surface and in intracellular compartments, active RTKs also recruit feedback and feed forward components (eg. phosphatases, downstream kinases, ubiquitin ligases) to form signaling nodes that magnify the spatial aspect of their output. These multiple modes of spatial control allow the cell to autonomously fine-tune its response to a given environmental stimulus. In turn, the mechanisms used by individual cells to spatially control RTK activity are coordinated to control the development, homeostasis and movement of multicellular tissues. Given that spatial regulation of RTKs is critical for many aspects of normal development and tissue homeostasis, and that RTK activity drives many types of cancer, aberrant spatial regulation of RTKs likely plays an underappreciated role in cancer development and progression. We begin this review by discussing how normal cells and tissues spatially control RTK activity. We then present specific examples of spatially deregulated RTKs in cancer and a consideration of how spatial RTK deregulation may underlie other well-known hallmarks of tumorigenesis. Finally, we address the need for a greater understanding of how spatial regulation of RTKs could impact ongoing efforts to therapeutically target RTKs – a major challenge in the treatment of human cancer.

Mechanisms of RTK spatial regulation

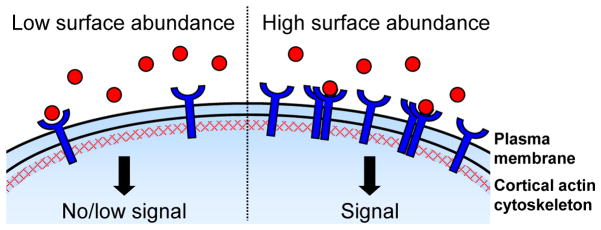

Lateral membrane distribution of RTKs

The traditional view of RTK activation involves ligand-induced receptor homo- or hetero-dimerization in which the ligand directly or indirectly stabilizes the interaction between two receptors5, 6. However, increasing evidence from structural and other studies indicates that many RTKs also form dimers and higher order oligomers (clusters) in the absence of ligand; such ligand-independent receptor clusters may either be active or ‘primed’ for ligand-dependent activation4, 7–14. Since monomeric RTKs cannot activate downstream signaling due to cis-autoinhibition of the tyrosine kinase domain that is released only upon receptor dimerization6, control of the abundance and distribution of individual RTKs at the membrane represents a key rate-limiting step in receptor activation – a step that dictates not only how likely it is that a given receptor will dimerize or cluster, but also the identity of its interacting partner(s) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. RTK surface abundance and distribution.

Controlling receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) surface abundance and distribution is a critical regulatory step since the activation of downstream signaling requires RTK dimerization. Locally high surface levels of an individual RTK may promote homodimerization and/or clustering (shown here), while high surface abundance of two or more RTKs may also increase heterodimer pairing. Distinct domains within the plasma membrane as well as the closely apposed and dynamic cortical actin cytoskeleton affect this key step in receptor activation.

The effective RTK surface abundance is controlled by the intracellular production of receptors, delivery to and turnover of receptors at the plasma membrane, and the compartmentalization of receptors within the plasma membrane – processes that are tightly integrated (Fig. 2a). In the absence of ligand, the abundance of unstimulated receptors at the cell surface is controlled via production and continuous recycling. Upon stimulation, ligand-dependent internalization can result in either receptor recycling or degradation, depending on the identity of the receptor, on the ligand concentration, and/or on the tight spatial control of both receptors and endocytic machinery across the cell cortex.

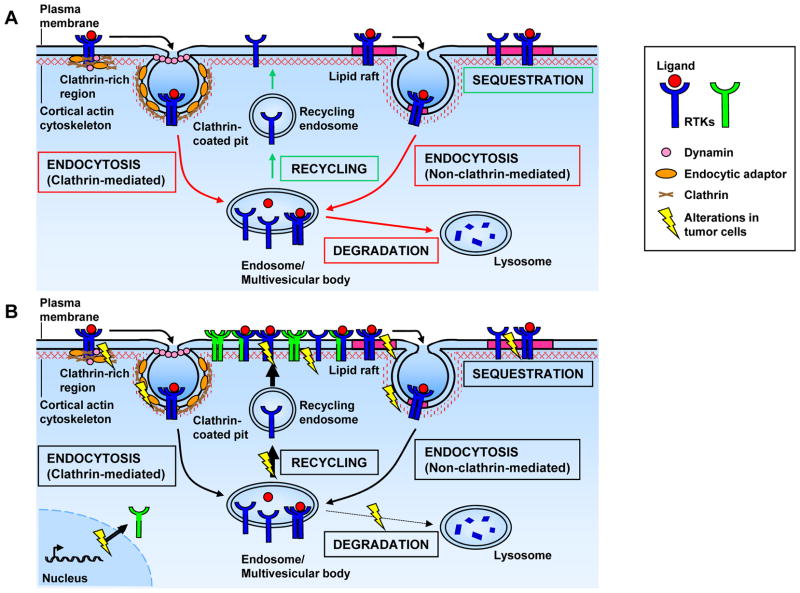

Figure 2. Mechanisms controlling RTK surface abundance and distribution.

A) Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) surface abundance is largely controlled by receptor endocytosis, which ultimately leads to receptor degradation or recycling. Stimulated (ligand-bound) or unstimulated (unbound) RTKs can be localized in plasma membrane domains such as clathrin-rich regions or lipid rafts, resulting in their endocytosis (via clathrin-coated pits or lipid rafts) or sequestration (in lipid rafts). B) In tumor cells, altered plasma membrane domains, cytoskeletal organization and/or vesicular trafficking can significantly affect RTK distribution and signaling by increasing the abundance/clustering of RTKs on the plasma membrane. In addition, RTK amplification or overexpression can lead to increased surface abundance, clustering and signaling as well as altered dimer pairing. In the example shown here, ErbB2 (represented here by the green RTK) is amplified or overexpressed, as it is in many human breast tumors151. ErbB2 is a unique RTK in that it does not require ligand-binding for activation; thus, increased surface levels of ErbB2 lead to ligand-independent clustering and downstream signaling135. ErbB2 amplification/overexpression also allows for increased heterodimerization with – and therefore activation of – other ErbB family members. Finally, mutations in RTKs themselves can affect their lateral or axial distribution and signaling.

It is increasingly appreciated that the plasma membrane is not homogeneous; rather, it is partitioned into nanometer-scale domains that can dramatically impact receptor distribution and signaling15–19. These domains are created by the differential distribution of lipids and proteins in concert with the underlying cortical cytoskeleton - a meshwork of actin filaments and other cytoskeletal components that is closely apposed to the plasma membrane. The interaction of cytoskeletal proteins with membrane lipids and/or transmembrane receptors and associated protein complexes can ‘corral’ many types of receptors, including RTKs, within the membrane, increasing or decreasing their propensity to cluster and signal20, 21. Studies of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR/ErbB1; Box 1) clustering across the plasma membrane have revealed a surprisingly heterogeneous and variable distribution of dimers and higher order clusters across the membrane of individual cells10, 22–24. Although little is known about the clustering of other EGFR family members (ErbB2, ErbB3 and ErbB4), the distribution of EGFR, ErbB2 and ErbB3 within the same cell can be markedly different, highlighting how little we know about the spatial control of this therapeutically critical family of RTKs12, 23, 25. The impact that spatial control can have on RTK signaling is exemplified by studies of Eph RTKs and their transmembrane ligands, ephrins. For example, restricting the lateral distribution of activated EphA2 receptors prevents the coalescence of microclusters into higher-order clusters and alters signaling output26. Indeed, the organization of the cortical cytoskeleton itself likely plays a key role in controlling RTK clustering. For example, a recent study suggests that cortical actin can promote the asymmetric distribution of pre-formed EGFR dimers, possibly enabling cells to rapidly respond to stimuli in a polarized manner such as during directed cell migration13. Thus RTK distribution and signaling can be linked to the physical properties of the cell cortex via the organization of the cortical cytoskeleton. These studies provide just a glimpse into how cells may exploit this underappreciated spatial dimension of RTK control to sense and respond to a dynamic environment.

Compartmentalization of the cell cortex can also affect the trafficking of receptors to and from the cell surface by impacting the distribution of the endocytic machinery itself15, 27, 28 (Fig 2a). For example, clathrin-coated structures can assemble from pre-designated membrane domains that sequester clathrin and other endocytic proteins to facilitate rapid and repetitive endocytosis29, 30. Increasing evidence suggests that the distribution of such clathrin “hot spots” is dependent upon the cortical cytoskeleton29, 30. Alternatively, regions of the plasma membrane that are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids known as lipid rafts (also known as sterol- or detergent-rich membrane domains) can also profoundly impact the distribution and endocytosis of RTKs18, 31(Fig. 2a). Depending on the receptor and cellular context, lipid raft localization can enhance or prevent RTK internalization and signaling by impacting receptor association with components of the endocytic machinery. Thus, some studies conclude that lipid raft association promotes EGFR signaling while others conclude that EGFR is activated upon release from lipid rafts32. Internalization of RTKs from lipid rafts occurs in a clathrin-independent manner and can yield a distinct outcome, as compared to clathrin-dependent endocytosis. For example, in some cells lipid raft-internalized EGFR is preferentially routed to the lysosome for degradation, while clathrin-internalized EGFR is recycled33. Thus, the localization of EGFR to lipid rafts versus clathrin-rich regions can greatly affect its surface abundance, and consequently its signaling. Similarly, the RET RTK associates with different adaptor proteins whether it is localized within or outside of lipid rafts, which may dictate the duration and biological outcome of downstream signaling34.

Lipid rafts can also function as platforms for the assembly of membranous and cytoplasmic signaling molecules, the lateral clustering of which forms a signaling compartment that is well segregated from non-raft proteins. For example, upon interaction with the EphB2 RTK, the transmembrane ligand ephrin-B1 clusters within lipid rafts where it recruits and activates a multiprotein signaling complex35, 36. Alternatively, lipid raft-association of a ligand can serve to prevent autocrine activation of its cognate RTK. For example, autocrine activation of the non-raft associated RTK fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) in skeletal muscle can be prevented by the sequestration of its ligand, FGF-2, in lipid rafts37.

Membrane distribution of RTKs in tissues

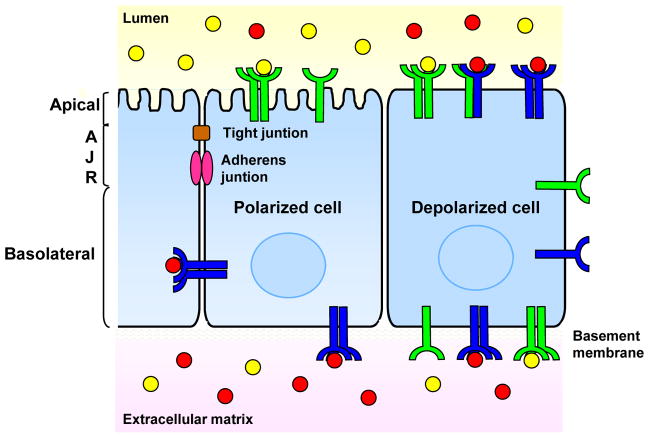

Beyond the nanometer-scale domains formed within the plasma membrane of individual cells, cells within tissues work together to establish larger macrodomains of the plasma membrane that affect receptor distribution. These macrodomains are both established within individual cells and coordinated among cells within a tissue38. Central to this coordination are the contacts between cells that establish membrane asymmetry and allow cells to physically sense and respond to one another. For example, epithelial cell-cell junctions (adherens junctions and tight junctions) form a boundary that segregates the membrane into apical and basolateral domains, distinct lipid:protein environments to which RTKs are differentially recruited and retained39 (Fig. 3). Epithelial cell-cell junctions are thought to both provide a positional cue for the maintenance of apical and basolateral membranes (and thus, apical-basal polarity) via protein trafficking and form a molecular ‘fence’ that physically prevents the diffusion of receptors and other membrane proteins from one domain to the other. Regulated vesicular transport between these two domains, known as transcytosis, or breakdown of the tight junction is required for proteins on one side to interact with those on the other. This boundary can therefore have a dramatic impact on the clustering of RTKs and/or their interaction with cell-autonomously provided (autocrine) ligands. Moreover, given that growth factors can be specifically presented to the apical or basolateral surfaces via other cell types, extracellular matrix or body fluids, this boundary can also dictate whether a given receptor can respond to non-cell-autonomous (paracrine) sources of ligand (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Spatial control of RTK signaling by cell polarization.

Localization of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) to either the apical or basolateral surface dictates whether they can be activated by secreted ligands. For example, activation of RTKs can be promoted by directing their localization to either the apical or basolateral surface where they can interact with luminally- or basolaterally-provided ligands. Alternatively, activation of RTKs can be prevented by sequestering them from ligand by cell polarization (see example in text). Loss of polarity is a hallmark of epithelial cancers that most certainly yields altered spatial distribution of RTKs. Without defined apical and basolateral surfaces to which RTKs can be targeted and segregated from one another and/or their ligand(s), RTKs in depolarized cells can dimerize with receptors and/or be activated by ligands that are not normally available in a polarized cell, resulting in aberrant RTK signaling.

The biological importance of spatially controlling the polarized distribution of RTKs in vivo was first recognized in Caenorhabditis elegans. The worm has a single EGFR family member, let-23, whose function is critical for the development of the vulva - the egg-laying organ40, 41. During vulval development, the anchor cell secretes the EGF-like ligand lin-3 to activate let-23 on the basolateral surface of adjacent vulval precursor cells and specify primary vulval cell fate. In 1996, Hoskins et al. and Simske et al. reported that loss of function mutations in genes encoding the PDZ domain-containing proteins lin-2 or lin-7 cause apical mislocalization of let-23 and abrogate its function in vulval cell fate determination42, 43. Thus let-23 must be localized to the basolateral surface of the vulval precursor cells facing the anchor cell in order to receive the paracrine anchor cell-derived signal.

An example of the cell autonomous segregation of receptor and ligand is provided by studies of the human airway epithelium, which constitutively secretes the growth factor neuregulin (Nrg) and expresses its receptors, ErbB3 and ErbB4. Despite the ability of Nrg-activated ErbBs to promote cellular proliferation, airway epithelial cells are largely quiescent due to the polarized segregation of Nrg from its receptors. In differentiated airway epithelial cells, Nrg is secreted exclusively into the apical fluid, while ErbBs are sequestered basolaterally. This arrangement yields ligand-receptor pairs that are poised for autocrine activation upon loss of epithelial integrity. Indeed, wounding the epithelial layer activates ErbBs at the wound edge, triggering proliferation and promoting wound closure and restoration of cell polarity; similarly, when apical-basal polarity or tight junctions are experimentally disrupted, Nrg gains access to its receptors44.

In addition to providing a positional cue that guides the distribution of RTKs and their ligands, cell junctions are important transmitters of physical information that can more directly regulate RTKs. For example, the spatial restriction of RTKs at the plasma membrane by the cadherin family of cell-cell adhesion receptors is thought to underlie, in part, the poorly understood phenomenon of contact-dependent inhibition of proliferation45–47. In culture, untransformed cells of many types stop dividing upon reaching confluence despite the continued presence of abundant growth factors – even when growth factors are provided to both the apical and basolateral surfaces. Therefore signaling from RTKs can be inhibited by cell-cell contact. In vivo all cells in a given tissue are in contact; therefore this process must be overridden during development and tissue homeostasis.

In non-confluent endothelial cells, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces activation and internalization of VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2) yielding continuous mitogenic signaling45, 46, 48. In contrast, confluent cells do not proliferate in response to VEGF; instead, VEGFR2 associates with vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) at adherens junctions and is not internalized. It has been proposed that the density-enhanced phosphatase-1 (DEP-1), which is also recruited to adherens junctions, mediates dephosphorylation of VEGFR2, preventing internalization and continuous proliferative signaling45, 46. Consistent with these findings, blocking VE-cadherin function or expression in 3D endothelial cultures enhances VEGFR2-dependent sprouting49.

In response to cell-cell contact, EGFR can also be restricted to a non-signaling, non-internalizing plasma membrane compartment47, 50–53. This property is dependent upon E-cadherin engagement and, importantly, seems to reflect the cells’ ability to sense the amount of cadherin-mediated contact with which they are engaged. For example, cadherin levels, cell junction ‘status’ (ie. mature or remodeling), strength of adhesion to the underlying extracellular matrix (which, in turn, controls the extent of cell-cell contact) or position within a cluster of cells can all profoundly effect EGFR activity within individual cells, in turn, creating spatial patterns of EGFR activity within multicellular tissues47, 52, 53. The mechanistic basis of this remains to be elucidated, but could reflect altered RTK clustering/signaling as a consequence of cell shape-driven changes in cortical cytoskeletal organization. Regardless of the mechanism, these data suggest that physical parameters within a tissue can directly contribute to the spatial control of RTK signaling.

Dynamic localization of RTKs in tissues

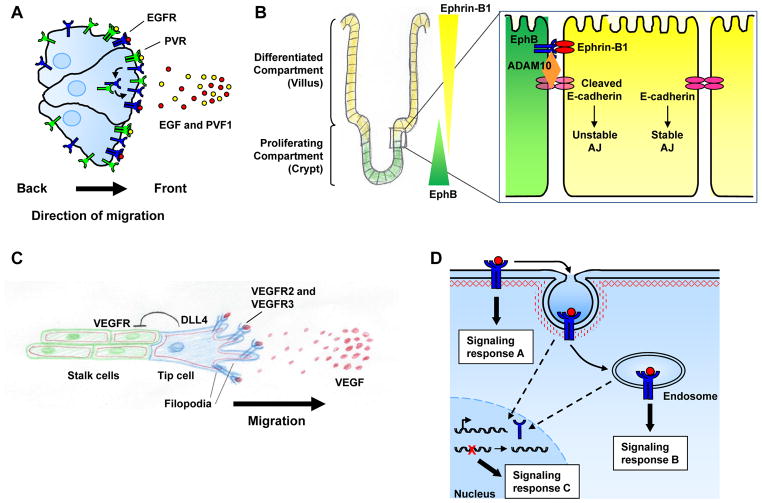

Beyond the constitutive spatial distribution of RTKs within mature polarized epithelia, the transient spatial restriction of RTKs contributes to dynamic processes such as directed cell migration, tissue morphogenesis and angiogenesis54, 55. Border cells in the Drosophila ovary provide a compelling example of the role of spatial RTK localization during directed cell migration in vivo (reviewed in Ref. #56). The anterior follicular epithelium within the fly ovary contains a group of border cells that invade the underlying germline tissue and migrate to the posterior-localized oocyte. Studies from several groups have revealed that two RTKs expressed on border cells, EGFR and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)/VEGF-related receptor (PVR), sense ligands expressed by the oocyte, and direct the border cells to them56. During this process, the level of RTK signaling is not critical; instead, spatially localized RTK activity is required for proper guidance (Fig. 4a). Jekely et al. found that inhibiting endocytosis in border cells yields loss of leading edge phosphotyrosine (facing the source of ligand), delocalized guidance signaling and severe migration defects, suggesting that endocytosis of active RTKs at the leading edge facilitates recycling and continued reception of the directional cue56, 57.

Figure 4. Spatial control of RTK signaling during tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis.

A) The distribution and endocytic recycling of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) at the front of a migrating cell (or group of cells) can promote continued RTK activation and migration toward secreted ligands, suggesting that RTK recycling to this region allows continued receipt of the directional cue. The example depicted here is that of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-related receptor (PVR) in Drosophila border cell migration (see text). B) Spatial patterning of RTK activity plays a central role in tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis. In the intestine, the differential localization of Ephs and ephrins controls cell positioning along the crypt-villus axis. Bidirectional signaling establishes a physical boundary between adjacent EphB- and ephrin-B1-expressing cells via an E-cadherin-mediated mechanism that alters cell-cell adhesion between these cell types (see text). Modified with permission from Ref. #59. C) VEGF receptor (VEGFR) helps define the identity of tip cells during angiogenic sprouting. Expression of VEGFR in the tip cell induces Delta-like 4 (DLL4), increasing Notch signaling and downregulating VEGFR2 expression in neighboring stalk cells. Tip cells localize VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 to filopodia to direct their migration towards a VEGF gradient. D) Activated RTKs can have distinct signaling outputs depending on their plasma membrane or endosomal localization. In fact, some RTKs – including EGFR and Trk – can assemble different signaling complexes depending on their axial localization (signaling responses A and B, see text). Several RTKs can also elicit distinct signaling responses from the nucleus (signaling response C, see Box 2).

Spatial patterning of RTK activity can also play a central role in the dynamic processes of tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis. An example is given by the differential localization of Ephs and ephrins that controls cell positioning along the crypt-villus axis during intestinal epithelial homeostasis (Fig. 4b). Bidirectional signaling establishes a physical boundary between adjacent EphB- and ephrin-B1-expressing cells58. This occurs via a mechanism in which EphB signaling activates the metalloproteinase ADAM10 at sites of cell-cell adhesion, inducing the shedding of E-cadherin at EphB-ephrin-B1 contacts and decreasing the affinity between the two cell populations 59. It is thought that migration out of the crypt may be regulated by such differential adhesion59. In addition, the position of the EphB-ephrin-B1 boundary along the crypt-villus axis affects the exposure of cells to other signals such as Wnt; in this way EphB/ephrin-B1 patterning controls both proliferation and differentiation during intestinal homeostasis60. This example illustrates a reiteratively used principle during morphogenesis and homeostasis: the cell that provides the RTK signal defines itself as distinct from the cell that receives it. In another well-studied example, activation of EGFR by one cell can inhibit or enhance EGFR signaling in its neighboring cells through feed-back or feed-forward control of ligand, receptor, or cellular inhibitors/activators, driving the patterning of several epithelial tissues in Drosophila, including the embryonic ectoderm, eye and ovary61, 62.

A similar use of this principle results in the distinction between tip and stalk cells that orchestrates both tracheal branching in Drosophila and angiogenic sprouting in vertebrates. In each case, tip cells define themselves as distinct from stalk cells, in part, by the expression of a specific RTK (FGFR/Breathless in Drosophila and VEGFR in vertebrate endothelial cells) that modulates the Notch pathway, a key regulator of cell fate and patterning processes in a variety of organisms54. For example, VEGF signaling in tip cells upregulates the expression of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4, increasing Notch signaling and downregulating the expression of VEGFR2 in neighboring stalk cells63, 64 (Fig. 4c). During angiogenic sprouting, the tip cell itself localizes VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 specifically to filopodia, where they detect an extracellular gradient of VEGF ligand to direct filopodial extension and migration/sprouting65, 66.

Control of intracellular RTK localization

While conventional models depict RTKs that signal from the plasma membrane before undergoing endocytosis to attenuate signaling, mounting evidence indicates that RTKs remain active in endosomal compartments (reviewed in Refs #67–69). In fact, for some RTKs internalization is required for a complete signaling response. Moreover, certain RTKs can activate distinct effectors from the plasma membrane versus the endosome, yielding yet another level of spatial control (axial). The idea that endosomes sustain and localize RTK signaling within the cell instead of merely attenuating it was originally put forth in the mid-1990s by Bergeron and colleagues, who observed that shortly after EGF stimulation, most activated EGFR colocalized with its associated signaling molecules SHC, GRB2, and mSos in early endosomes, suggesting that signaling continues from this compartment70, 71. To confirm this idea, Vieira et al. blocked endocytosis using a dominant negative dynamin mutant and showed that inhibiting EGFR internalization resulted in phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ1 and SHC, but significantly reduced activation of ERK1/ERK2 and PI3K, indicating that different sets of signaling molecules are activated on the plasma membrane versus endosomes72. In another example, inhibition of nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced internalization of the TRKA (also known as NTRK1) RTK in PC12 cells enhanced survival responses mediated by TrkA-dependent activation of PI3K and Akt at the plasma membrane, but inhibited differentiation mediated by TrkA-dependent Erk1/Erk2 activation in endosomes73. In fact, NGF stimulates the assembly of a stable signaling complex containing TrkA, Rap-1 and Erk1/Erk2 in endosomes that is not formed at the plasma membrane; thus, differentially localized RTKs can transmit distinct signals, making axial spatial regulation a critical factor in determining their biological output74 (Fig. 4d).

More recent studies have demonstrated that other RTKs also continue to signal from endosomes, including the insulin receptor75, PDGF receptor (PDGFR)76, VEGFR246, 77 and VEGFR378. Since receptor-effector pairing at the plasma membrane and on endosomes varies among receptors, controlling the internalization machinery could equate to different signaling outcomes for distinct RTKs. Endosomal signaling may also confer several advantages to the cell, such as increased signaling specificity and protection from cytosolic phosphatases, ubiquitin ligases, and proteases. Moreover, endosomes can act as transport modules, employing microtubule motors to provide rapid delivery of signals from the plasma membrane to targeted subcellular locations that may be quite a distance away. For example, upon NGF-mediated activation of TrkA at an axon terminal, endosomal transport of the active NGF-TrkA complex along the axon to the cell body is required to promote signaling events in the nucleus79, 80. In fact, this provides a fascinating example of how lateral and axial regulation can be integrated. Neurotrophin-mediated (NGF and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)) stimulation of Trk receptors on the cell body leads to activation of Erk1/Erk2 and Erk5 in the nucleus; in contrast, stimulation of Trk receptors on distal axon terminals activates Erk1/Erk2 and Erk5 locally, but selectively activates only Erk5 in the nucleus following endosomal transport to the cell body81. Importantly, these Erk family MAP kinases activate distinct groups of transcription factors; thus, the lateral localization of Trk receptors on the neuronal plasma membrane as well as the axial transport of activated Trk signaling complexes combine to influence gene expression. Beyond endosomal signaling, RTKs themselves have been reported to travel from the cell surface to the nucleus where they may have additional biological outcomes due to their roles in transcriptional regulation and DNA repair (Fig. 4d; Box 2).

Box 2. Emerging roles of nuclear RTKs.

Numerous reports describe the translocation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), ERBB2, ERBB3, ERBB4, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), TRKA, and MET, to the nucleus (reviewed in Refs. #140–143). Nuclear EGFR, first reported in hepatocytes during liver regeneration, has been the most extensively studied144. The carboxyl-terminus of EGFR displays intrinsic transactivation activity and can activate target genes such as CCND1 (which encodes cyclin D1), AURKA (which encodes Aurora kinase A), NOS2 (nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible) and MYBL2 (myb-like protein 2), promoting cell proliferation and genome instability (reviewed in Refs. #142,143). Nuclear EGFR has also been reported to promote DNA repair, replication and radio-resistance by activating DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), and/or phosphorylating and stabilizing chromatin-bound proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). The presence of nuclear EGFR has been reported in several cancers, and is associated with a poor prognosis; for example, nuclear localization of a constitutively activated EGFR variant, EGFRvIII, has been correlated with poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer, invasive breast cancer and glioblastoma145–147. Moreover, several reports suggest that nuclear EGFR is associated with resistance to conventional chemotherapies and to EGFR-targeted therapies (reviewed in Refs. #142,143). Nuclear ErbB2 and ErbB3 have also been reported in cancer; in fact, like EGFR, increased levels of nuclear ErbB3 correlate with advanced prostate cancer148, 149.

Given their correlation with poor clinical outcome and their role in therapeutic resistance, nuclear ErbB receptors are emerging as important biomarkers in cancer and therapeutic response. It is not clear, however, how intact RTKs are transported from their plasma membrane localization into the nucleus. Rather, the best-characterized route of RTK nuclear localization relies on proteolytic cleavage by membrane-associated proteases to release cytoplasmic RTK fragments that are transported into the nucleus by conventional mechanisms (reviewed in Refs. #140,150). Clearly, a realization of their potential as biomarkers will require a greater understanding of these mechanisms.

Spatial deregulation of RTKs in cancer

Recognition of the importance of spatially regulating RTKs in normal cells and tissues is accompanied by the realization that the role of spatial deregulation of RTKs in tumorigenesis may be vastly underappreciated. In addition to the recent identification of oncogenic mutations that spatially deregulate specific RTKs, spatial deregulation is likely a primary consequence of other well-known oncogenic mutations and phenotypic hallmarks of tumor cells. For example, overexpression, amplification or mutation of RTKs themselves can alter their spatial distribution. Alternatively, spatial deregulation of RTK signaling may underlie the prominent occurrence of altered trafficking, polarity, cell adhesion or cytoskeletal organization in cancer development and progression. The development of high-resolution methods for detecting RTK activity in normal and tumor tissues will be essential for studying the role of spatial RTK patterning in the heterogeneous tumor environment. Spatial regulation could critically impact both the response of tumors to targeted RTK inhibitors and the subsequent mechanisms of resistance that emerge.

Altered lateral RTK distribution in tumor cells

Gene amplification or overexpression is a common mechanism of RTK deregulation in many cancers that not only yields increased surface abundance and signaling, but also likely alters the lateral distribution, clustering and dimeric partnering of RTKs (Figs. 1,2b). For example, many studies suggest that ErbB2 amplification alters the complex equilibrium of ErbB2- and ErbB3-containing dimers and/or clusters in breast cancer cells, consequently shifting their signaling output and dependencies12, 82–85. Similarly, MET amplification can drive ErbB3-dependent PI3K signaling, thereby mediating lung tumor resistance to EGFR inhibitors86, 87. Although the mechanism is unknown, this is thought to occur via physical collaboration between MET and ErbB3, which MET does not normally activate86. Although ErbB family members and other RTKs are amplified or overexpressed in many cancers, few studies have examined how an increase in one RTK impacts the spatial equilibrium and signaling output of others.

Alterations in proteins that compartmentalize the plasma membrane and confer spatial control of RTKs are also found in many cancers (Fig. 2b). For example, mutation or deregulation of caveolin-1 (Cav1), an architectural component of caveolae (a subset of lipid rafts) occurs in a variety of human cancers. By binding and sequestering certain receptors, including EGFR and ErbB2 at the plasma membrane, presumably in lipid rafts, Cav1 can inhibit proliferative signaling and may therefore function as a tumor suppressor88, 89. Indeed, the Cav1 gene is located in a chromosomal region that is frequently deleted in several tumor types90, 91. Similarly, a dominant-negative Cav1 mutation is found in a subset of primary human breast cancers92. In contrast, Cav1 is re-expressed or maintained in some advanced metastatic tumors, often correlating with a poor prognosis91, 93. In fact, it has recently been reported that hypoxia-induced upregulation of Cav1 promotes clustering of EGFR within caveolae, leading to ligand-independent activation94. This complex relationship between Cav1 expression and tumorigenesis likely depends on whether the RTKs that are active in a specific tumor normally employ caveolae to inhibit or enhance signaling. Similarly, alterations in components of the clathrin machinery and subsequent steps in vesicular trafficking are frequently found in human cancer (Fig. 2b).

Alterations in cortical cytoskeleton organization and function also likely alter RTK distribution, clustering and signaling in a cell autonomous manner. In support of this, an intriguing recent study found that the actomyosin-dependent mobility of activated EphA2 receptors in the plasma membrane of breast cancer cells is highly correlated with their metastatic potential26. In another example, the cortical cytoskeleton-associated neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) tumor suppressor, Merlin, can control the lateral mobility and distribution of activated EGFR within the plasma membrane47, 95.

Altered RTK distribution in tumor tissues

Loss of polarity and contact-dependent inhibition of proliferation are early and universal hallmarks of tumorigenesis96, 97. Given the role of apical-basal polarity and cell-cell junctions in spatially controlling RTK signaling, alterations of essential cell polarity or cell junction components will almost certainly yield deregulated RTK activity (Fig. 3). In fact, several key cell polarity and cell junction proteins have tumor suppressor activity in vivo.

Apical-basal polarity is largely maintained by the Crumbs, Par and Scribble polarity complexes. The first indication that deregulated polarity could contribute to tumorigenesis was provided by studies in Drosophila that revealed that loss of function mutations in Scribble complex proteins resulted in both mislocalization of apical determinants to the basolateral membrane and uncontrolled proliferation98. Altered expression or mislocalization of Scribble and other polarity proteins have also been reported in many human cancers97, 99–103. Although RTKs have not yet been directly implicated in the neoplastic phenotype exhibited by Drosophila polarity mutants, it is notable that genes encoding several endocytic proteins have been identified as either modifiers of polarity mutants or as tumor suppressors themselves104. Moreover, a recent study in zebrafish revealed that loss of a Scribble complex protein, Lethal giant larvae (Lgl), results in activation of ErbB signaling, which in turn drives epidermal proliferation and induction of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)105. This finding suggests that aberrant RTK activation may underlie the overproliferation phenotypes of polarity mutants. Mounting evidence indicates that autocrine activation of RTKs occurs in many human cancers, including ErbB3 in lung, ovarian, and head and neck cancers106–108. While aberrant ligand production may be responsible in some tumors, the cell-autonomous ligand-receptor interactions that are permitted following loss of polarity may be an underappreciated mechanism of autocrine RTK signaling in human cancer.

Alterations in the cell adhesion machinery have also been implicated in human cancer and in this case, deregulated RTK signaling has been directly implicated. For example, loss of E-cadherin has been linked to the initiation and/or progression of many cancers. Germline inactivating mutations in CDH1 (which encodes E-cadherin) can cause diffuse gastric cancer in humans; deregulated EGFR signaling has been linked to the inherent invasive behavior of these tumors109, 110. In fact, loss of E-cadherin is also a hallmark of EMT that is thought to drive malignant progression111. Aberrant EGFR signaling also accompanies EMT in many cancers, where EMT is associated with resistance to EGFR inhibitors112. Indeed, the obvious parallels between the invasive behavior of tumor cells and orchestrated cell movements during development – including both EMT and the example of RTK-driven border cell migration in Drosophila – strongly suggest that aberrant spatial activation of RTKs contributes to tumor invasion driven by loss of polarity, contact-dependent inhibition of proliferation and EMT. In support of this, recent studies suggest that, as in border cell migration, the endocytic turnover of PDGFR drives the invasive properties of glioblastoma cells and the recycling of EGFR coupled with α5β1 integrin drives the migration of ovarian cancer cells113, 114.

Loss or mutation of α-catenin (encoded by CTNNA1), an essential core component of the adherens junction, has also been found with increasing prevalence in human cancers115. In fact, the NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, which stabilizes adherens junctions and directly interacts with α-catenin, mediates contact-dependent inhibition of EGFR internalization and signaling47, 116. Pharmacologic inhibitors of EGFR can reverse the overproliferation of Merlin-deficient cells in culture and in vivo, underscoring the role of deregulated RTK signaling in Merlin-deficient tumors47, 117, 118.

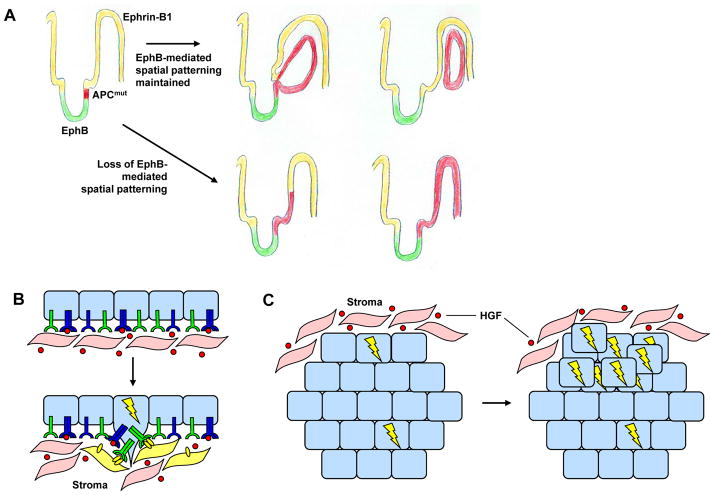

It is increasingly appreciated that a tumor is not a uniform collection of cells but rather a heterogeneous and interdependent community of cells that interact with each other and with surrounding normal cells96, 119. Thus, the patterned distribution of RTK activity among cells in the tumor environment could play a critical role in the initiation and progression of many tumor types (Fig. 5). The Ephs once again provide a glimpse into how important spatial RTK distribution may be in this context. Recent studies have shown that loss of EphB-mediated cell compartmentalization in the intestine completely alters adenoma formation induced by mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor, ultimately rendering them larger, more numerous and more advanced120 (Fig. 5a). Prostate cancer cells can also co-opt Eph signaling to promote aberrant interactions with stromal cells, thereby facilitating invasive behavior121 (Fig. 5b). Thus patterns of RTK activation within the developing tumor and microenvironment may play a significant role in the biology the tumor.

Figure 5. Spatial deregulation of RTKs in tumor tissues.

A) Loss of EphB-mediated spatial patterning in the small intestine can profoundly affect intestinal tumorigenesis. Top row: Fully malignant EphB-expressing tumor cells are restricted from expanding into the adjacent ephrin-B1-expressing compartment created by EphB-ephrin-B1 spatial patterning. Bottom row: When EphB-mediated spatial patterning is lost (ie. when EphB-signaling is lost), EphB-expressing tumor cells expand throughout the ephrin-B1 compartment; these tumors are larger, more numerous and more advanced120. Modified with permission from Ref. #120. B) Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) alterations in tumor cells can promote aberrant interactions with the surrounding stroma. For example, increased levels of EphB3 and/or EphB4 receptors in prostate cancer cells may allow these cells to exploit ephrin-B2 ligand produced by stromal fibroblasts to promote invasion. Indeed, the mis-expression of various Ephs/ephrins has been reported in prostate, colon, and breast cancer152. C) The spatial distribution of RTKs within a tumor can play a key role in the development of resistance to targeted therapeutics. Tumor cells located at the tumor periphery can co-opt stromal ligand, whereas cells located in the tumor center may require ligand-independent mechanisms of activation. For example, expansion of MET-amplified (denoted by bolt), ErbB-inhibitor resistant lung tumor cells can be promoted by local, stroma-produced HGF87.

Altered axial RTK distribution in tumors

Defective vesicular trafficking is emerging as a key contributor to cancer122, and likely plays a significant role in oncogenic RTK signaling. Indeed, alterations in various components of the endocytic and recycling pathways have been reported in human tumors (reviewed in Ref. #122); these can derail the spatial restriction of RTK signaling both indirectly and directly. Since plasma membrane macrodomains require vesicular trafficking to maintain their identities, RTK localization can be altered indirectly by the disruption of these domains. For example, cell-cell junctions and apical-basal polarity are dynamically maintained by the constitutive endocytosis and recycling of membrane components123. Disrupted trafficking can yield loss of cell-cell junctions and polarity, abolishing the differential localization of RTKs to apical and basolateral membrane domains (Fig. 3). Impairing or enhancing endocytosis and/or recycling can also directly alter receptor distribution (Fig. 2b). Many of the alterations in endocytic/recycling components that have been identified in human tumors would be predicted to enhance recycling of RTKs and decrease their trafficking to lysosomes.

Recent studies directly support a role for altered trafficking in oncogenic RTK signaling. In the following examples oncogenic mutations in RTKs that are found in human malignancies alter their own trafficking124, 125. The RTK fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) is expressed on hematopoietic progenitor cells and regulates their survival, proliferation and differentiation. Internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations in the juxtamembrane domain of Flt3 (Flt3-ITD) not only yield constitutive ligand-independent activation of the receptor, but also impair its delivery to the plasma membrane, resulting in intracellular signaling. Activation of Flt3-ITD in intracellular compartments yields activation of signaling pathways that are distinct from those activated by the plasma membrane-localized receptor. While plasma membrane-targeted Flt3-ITD strongly activates the Akt and ERK1/ERK2 pathways, intracellular Flt3-ITD aberrantly activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5), an event that is recognized as an important step in myeloid transformation124.

Another recent study demonstrated that both activation and increased endosomal signaling are necessary for the tumorigenic and metastatic properties of MET125. Two distinct MET kinase domain mutations (METD1246N, METM1268T) identified in human papillary renal carcinomas render the receptor constitutively active and promote in vitro cell migration and growth in soft agar. Blocking endocytosis by numerous methods including mutation of the Grb2-binding site on MET preserved phosphorylation (and thus activation) of MET mutants but prevented their oncogenic behavior. Topical treatment of METD1246N or METM1268T -expressing tumors with endocytic inhibitors also prevented subcutaneous tumor growth. Surface biotinylation assays demonstrated constitutive internalization and recycling as well as impaired degradation of MET mutants compared to wild-type MET, however the mechanism(s) by which cells sort the mutants to recycling endosomes while targeting wild-type MET for degradation are not yet known. Identification of these pathways will be critical to exploit their differences therapeutically.

Therapeutic implications

Deregulated RTK signaling has been causally implicated in the development and progression of nearly all types of cancer, prompting a major effort to develop and test pharmacologic inhibitors of various RTKs126. Most translational studies measure overall RTK pathway strength using relatively uniform populations of cultured cells derived from individual tumors – usually permanent cell lines established under the selective pressures imposed by tissue culture conditions. However, the spatial distribution of RTK activity within individual cells and within the evolving tumor could have a critical impact on the success of such targeted therapies.

For example, differences in RTK dimerization and clustering caused by gene amplification, increased expression, distinct mutations or altered physical parameters such as loss of polarity or ECM stiffness could promote ligand-independent or kinase-independent activation of homotypic or collaborating RTKs. This could have a dramatic effect on the efficacy of ligand-blocking antibodies such as the EGFR inhibitor, cetuximab, or antibodies that disrupt the interaction of a specific RTK-containing dimer such as the ErbB2 dimerization inhibitor, pertuzumab127, 128. Even relatively subtle differences in clustering equilibrium among RTKs within individual tumor cells could significantly influence the pharmacodynamics of a particular drug.

Altered axial distribution of RTKs could also have a dramatic effect on therapeutic effectiveness. For example, an RTK mutation that drives aberrant signaling from within the endosome may not be targetable by ligand-blocking or other inactivating antibodies. Similarly, in some cases tumor cells express high levels of cleaved, intracellular or even nuclear forms of a particular RTK; these may also be differentially sensitive to available targeted therapies129. Spatial differences in RTK activity across the heterogeneous tumor microenvironment could also affect tumor responsiveness to targeted therapies; for example spatial deregulation of a particular RTK could drive invasion at the leading edge of the tumor but not proliferation in the tumor center or vice versa.

Finally, the spatial distribution of RTKs within the tumor and microenvironment could also be key drivers of resistance mechanisms. For example, the expansion of MET-amplified, ErbB-inhibitor resistant lung tumor cells may be promoted by local, stroma-produced HGF ligand87. Tumor cells that co-opt an environmentally produced ligand (eg. HGF) would respond differently than those that acquire ligand-independent mechanisms of activation (Fig. 5c). Therefore, the position of a cell within a tumor mass may critically impact its behavior during the evolution and therapeutic response of the tumor.

The concept of personalized medicine – developing a treatment plan based on the molecular signature of a tumor – has become a major focus of cancer research. Current efforts aim to define the gene mutation, mRNA expression, epigenetic and proteomic signatures of individual tumors. The spatial distribution of therapeutic targets (ie. RTKs) within individual cells and across a tumor could also have a dramatic impact on therapeutic efficacy; however, we still don’t know precisely how or where many clinically used RTK inhibitors act. In fact, structural models of RTK dimerization, activation and pharmacologic inhibition are far from complete. Recent efforts to design fluorescently-labeled versions of these drugs will provide excellent tools for probing their sites of action, and evolving structural models will lead to a greater understanding of exactly how these inhibitors function. Ultimately, this information can be exploited to design novel drugs that specifically regulate the distribution of RTKs or that specifically target a spatially localized population of RTKs.

Perspectives

The work of biochemists and cell biologists has yielded large bodies of work devoted to plasma membrane architecture and vesicular trafficking as means of spatially controlling receptors of all kinds. Likewise, developmental biologists, often studying model organisms, have uncovered some of the ways that cells spatially choreograph receptor signaling to drive tissue morphogenesis. The appreciation of the near-universal role that RTKs play in human cancer has cast a spotlight on this critical class of mitogenic receptors and effected an explosion of interest in RTKs as therapeutic targets. To maximize the promise of this translational focus it will be critical to bring developmental biologists, membrane receptor biologists and translational investigators together to assemble a three dimensional view of RTK activity in normal and tumor cells and tissues.

At a Glance Summary.

Deregulation of RTKs has been implicated in nearly all forms of human cancer. As such, RTKs are the object of major ongoing efforts to develop targeted cancer therapies.

Because of their broad roles in many critical cellular processes, RTKs are subject to tight regulation. The regulation of RTK production has been well-studied; mounting evidence indicates that spatial regulation of RTKs is also critical.

RTKs are spatially regulated in two dimensions - lateral and axial. The heterogeneous nature of the plasma membrane yields lateral compartmentalization of RTKs to both nanometer-scale and much larger macrodomains. Axial control of RTKs via endocytosis enables differential signaling from the plasma membrane and/or endosomes.

Spatial distribution of RTKs is important for many developmental processes including directed cell migration and branching morphogenesis. Regulated RTK distribution is also necessary for spatial patterning during cell fate specification and tissue homeostasis.

There are many ways in which deregulated spatial control of RTKs may contribute to tumorigenesis. For example, increased RTK production can yield altered plasma membrane distribution/clustering, defective tissue architecture can promote abnormal receptor-receptor and/or receptor-ligand interactions, and defects in vesicular trafficking can increase surface RTK levels and affect the location from which signaling occurs (eg. plasma membrane vs. endosome).

Despite accumulating evidence, the impact of spatial RTK signaling in tumorigenesis and therapeutic response is underappreciated. A three-dimensional view of RTK activity in tumor cells and tissues could yield a more complete understanding of the mechanisms of tumor progression and therapeutic resistance, leading to altered treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jeff Engelman for thoughtful comments on the manuscript, and members of the McClatchey lab for many creative discussions. This work was supported by NIH R01 CA113733 to A.I.M.

Glossary

- Autocrine

A mode of signaling in which a secreted substance acts on surface receptors present on the same cell that produced it

- Cell cortex

The outer margin of a cell containing the plasma membrane and underlying cortical cytoskeleton - a contractile, mesh-like structure that is rich in contractile actin-myosin filaments and other cytoskeletal components. The term cell cortex can also be used to refer to the cortical cytoskeleton alone

- Clathrin

A major protein component of the vesicular coat of specialized pits and vesicles involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis

- Adherens junction

A macromolecular complex containing adhesive transmembrane receptors (cadherins and nectins) and cytoplasmic regulators (catenins) that link the complex to the actin cytoskeleton. Adherens junctions undergo continuous remodeling and are necessary for cell-cell adhesion and the polarization of epithelial and endothelial cells

- Tight junction

A cell-cell adhesion complex that forms a semi-permeable barrier between the apical and basolateral surfaces of epithelial cells and contributes to cell polarity and signaling

- Apical–basal polarity

Epithelial cells are polarized, with an apical membrane that faces the external environment or a lumen and a spatially opposed basolateral membrane that functions in cell–cell interactions and contacts the basement membrane

- Paracrine

A mode of signaling in which a secreted substance acts on surface receptors present on other cells

- PDZ domain

A structural, protein-protein interaction domain of ~80-90 amino acids that often serves as a scaffold for signaling complexes and/or a cytoskeletal anchor for transmembrane proteins

- Crypt-villus axis

The longitudinal/vertical axis formed by a villus and its corresponding crypts in the small intestine

- Dynamin

A large GTPase that forms a helix around the neck of nascent endocytic vesicles to separate them from parent membranes

- Axon terminal

The distal termination of a presynaptic neuron

- Cell body

The part of a neuron containing the nucleus and surrounding cytoplasm, but not the axonal and dendritic extensions

- Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

A program whereby cells convert from an epithelial to a mesenchymal phenotype. This process, which is enacted during normal embryonic development, can be abnormally activated in carcinomas, resulting in altered cell morphology, the expression of mesenchymal proteins and increased invasiveness

References

- 1.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–65. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King N, Carroll SB. A receptor tyrosine kinase from choanoflagellates: molecular insights into early animal evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261477698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King N. The unicellular ancestry of animal development. Dev Cell. 2004;7:313–25. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bethani I, Skanland SS, Dikic I, Acker-Palmer A. Spatial organization of transmembrane receptor signalling. EMBO J. 2010;29:2677–88. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemmon MA. Ligand-induced ErbB receptor dimerization. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:638–48. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himanen JP, Nikolov DB. Eph signaling: a structural view. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton AH, et al. Ligand-induced dimer-tetramer transition during the activation of the cell surface epidermal growth factor receptor-A multidimensional microscopy analysis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30392–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barton WA, et al. Crystal structures of the Tie2 receptor ectodomain and the angiopoietin-2-Tie2 complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:524–32. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton AH, Tavarnesi ML, Johns TG. Unligated epidermal growth factor receptor forms higher order oligomers within microclusters on A431 cells that are sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitor binding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4589–97. doi: 10.1021/bi700002b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward CW, Lawrence MC, Streltsov VA, Adams TE, McKern NM. The insulin and EGF receptor structures: new insights into ligand-induced receptor activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S, et al. Mapping ErbB receptors on breast cancer cell membranes during signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2763–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung I, et al. Spatial control of EGF receptor activation by reversible dimerization on living cells. Nature. 2010;464:783–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08827. This study demonstrates that unliganded EGFR fluctuates between monomer and dimer states, and that pre-formed dimers are primed for ligand-binding and distributed asymmetrically across the cell cortex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo A, Szollosi J, Nagy P. Coclustering of ErbB1 and ErbB2 revealed by FRET-sensitized acceptor bleaching. Biophys J. 2010;99:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNiven MA. Big gulps: specialized membrane domains for rapid receptor-mediated endocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:487–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding AS, Hancock JF. Using plasma membrane nanoclusters to build better signaling circuits. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inder K, et al. Activation of the MAPK module from different spatial locations generates distinct system outputs. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4776–84. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lajoie P, Goetz JG, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:381–5. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grecco HE, Schmick M, Bastiaens PI. Signaling from the living plasma membrane. Cell. 2011;144:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusumi A, et al. Paradigm shift of the plasma membrane concept from the two-dimensional continuum fluid to the partitioned fluid: high-speed single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:351–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaqaman K, et al. Cytoskeletal control of CD36 diffusion promotes its receptor and signaling function. Cell. 2011;146:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.049. This study demonstrates that the cytoskeleton can control membrane receptor signaling by confining receptor diffusion within given membrane regions that serve to increase their collision frequency and clustering. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abulrob A, et al. Nanoscale imaging of epidermal growth factor receptor clustering: effects of inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3145–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.073338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy P, Claus J, Jovin TM, Arndt-Jovin DJ. Distribution of resting and ligand-bound ErbB1 and ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinases in living cells using number and brightness analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16524–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002642107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa MN, Radhakrishnan K, Edwards JS. Monte Carlo simulations of plasma membrane corral-induced EGFR clustering. J Biotechnol. 2011;151:261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufmann R, Muller P, Hildenbrand G, Hausmann M, Cremer C. Analysis of Her2/neu membrane protein clusters in different types of breast cancer cells using localization microscopy. J Microsc. 2011;242:46–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salaita K, et al. Restriction of receptor movement alters cellular response: physical force sensing by EphA2. Science. 2010;327:1380–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1181729. Reveals a spatio-mechanical mechanism whereby EphA2 signaling is regulated; the authors provide evidence that experimental restriction of ephrin-A1 impacts EphA2 activation and suggest that alterations in this mode of control may promote tumor cell invasion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchhausen T. Imaging endocytic clathrin structures in living cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lajoie P, Nabi IR. Lipid rafts, caveolae, and their endocytosis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;282:135–63. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)82003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaidarov I, Santini F, Warren RA, Keen JH. Spatial control of coated-pit dynamics in living cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:1–7. doi: 10.1038/8971. This first visualization of clathrin-coated pit dynamics in mammalian cells reveals that pits form repeatedly at discrete sites within the plasma membrane and are attached to the cortical cytoskeleton. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunez D, et al. Hotspots organize clathrin-mediated endocytosis by efficient recruitment and retention of nucleating resources. Traffic. 2011;12:1868–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Disanza A, Frittoli E, Palamidessi A, Scita G. Endocytosis and spatial restriction of cell signaling. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:280–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balbis A, Posner BI. Compartmentalization of EGFR in cellular membranes: role of membrane rafts. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:1103–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigismund S, et al. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012. This study provides evidence that the mechanism of RTK endocytosis can profoundly impact RTK signaling, as clathrin-mediated endocytosis of EGFR promotes receptor recycling and clathrin-independent endocytosis promotes degradation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paratcha G, et al. Released GFRalpha1 potentiates downstream signaling, neuronal survival, and differentiation via a novel mechanism of recruitment of c-Ret to lipid rafts. Neuron. 2001;29:171–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruckner K, et al. EphrinB ligands recruit GRIP family PDZ adaptor proteins into raft membrane microdomains. Neuron. 1999;22:511–24. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signalling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:165–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutierrez J, Brandan E. A novel mechanism of sequestering fibroblast growth factor 2 by glypican in lipid rafts, allowing skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1634–49. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01164-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:887–901. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellman I, Nelson WJ. Coordinated protein sorting, targeting and distribution in polarized cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:833–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferguson EL, Horvitz HR. Identification and characterization of 22 genes that affect the vulval cell lineages of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1985;110:17–72. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aroian RV, Koga M, Mendel JE, Ohshima Y, Sternberg PW. The let-23 gene necessary for Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction encodes a tyrosine kinase of the EGF receptor subfamily. Nature. 1990;348:693–9. doi: 10.1038/348693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoskins R, Hajnal AF, Harp SA, Kim SK. The C. elegans vulval induction gene lin-2 encodes a member of the MAGUK family of cell junction proteins. Development. 1996;122:97–111. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simske JS, Kaech SM, Harp SA, Kim SK. LET-23 receptor localization by the cell junction protein LIN-7 during C. elegans vulval induction. Cell. 1996;85:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81096-x. References 42 and 43 provide the first evidence that the distinct membrane localization of an RTK is critical for its activation, demonstrating that the C. elegans EGFR family member, let-23, must be localized to the basolateral membrane to be activated by its ligand. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermeer PD, et al. Segregation of receptor and ligand regulates activation of epithelial growth factor receptor. Nature. 2003;422:322–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01440. Direct demonstration of the physical segregation of ligand-receptor pairs by apical and basolateral domains to prevent receptor activation in differentiated mammalian epithelia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lampugnani MG, et al. Contact inhibition of VEGF-induced proliferation requires vascular endothelial cadherin, beta-catenin, and the phosphatase DEP-1/CD148. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:793–804. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lampugnani MG, Orsenigo F, Gagliani MC, Tacchetti C, Dejana E. Vascular endothelial cadherin controls VEGFR-2 internalization and signaling from intracellular compartments. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:593–604. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curto M, Cole BK, Lallemand D, Liu CH, McClatchey AI. Contact-dependent inhibition of EGFR signaling by Nf2/Merlin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703010. This study reveals that the NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, can associate with EGFR and inhibit its internalization specifically in a cell-cell contact-dependent manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrara N. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med (Berl) 1999;77:527–43. doi: 10.1007/s001099900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abraham S, et al. VE-Cadherin-mediated cell-cell interaction suppresses sprouting via signaling to MLC2 phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2009;19:668–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian X, Karpova T, Sheppard AM, McNally J, Lowy DR. E-cadherin-mediated adhesion inhibits ligand-dependent activation of diverse receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 2004;23:1739–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perrais M, Chen X, Perez-Moreno M, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin homophilic ligation inhibits cell growth and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling independently of other cell interactions. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2013–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JH, Kushiro K, Graham NA, Asthagiri AR. Tunable interplay between epidermal growth factor and cell-cell contact governs the spatial dynamics of epithelial growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11149–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812651106. Provides intriguing evidence that cells can modulate their sensitivity to EGF-activated signaling as a function of the amount of cell-cell contact with which they are engaged. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JH, Asthagiri AR. Matrix stiffening sensitizes epithelial cells to EGF and enables the loss of contact inhibition of proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1280–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.078394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Affolter M, Zeller R, Caussinus E. Tissue remodelling through branching morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:831–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–57. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montell DJ. Border-cell migration: the race is on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jekely G, Sung HH, Luque CM, Rorth P. Regulators of endocytosis maintain localized receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in guided migration. Dev Cell. 2005;9:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.004. This study shows that spatial restriction of RTK signaling via endocytosis and receptor recycling to a distinct membrane region of migrating cells is necessary for directed cell migration. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Batlle E, et al. Beta-catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the intestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of EphB/ephrinB. Cell. 2002;111:251–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solanas G, Cortina C, Sevillano M, Batlle E. Cleavage of E-cadherin by ADAM10 mediates epithelial cell sorting downstream of EphB signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1100–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pitulescu ME, Adams RH. Eph/ephrin molecules--a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2480–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shilo BZ. Regulating the dynamics of EGF receptor signaling in space and time. Development. 2005;132:4017–27. doi: 10.1242/dev.02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheung LS, Schupbach T, Shvartsman SY. Pattern formation by receptor tyrosine kinases: analysis of the Gurken gradient in Drosophila oogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eilken HM, Adams RH. Dynamics of endothelial cell behavior in sprouting angiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benedito R, et al. Notch-dependent VEGFR3 upregulation allows angiogenesis without VEGF-VEGFR2 signalling. Nature. 2012;484:110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerhardt H, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1163–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nilsson I, et al. VEGF receptor 2/-3 heterodimers detected in situ by proximity ligation on angiogenic sprouts. EMBO J. 2010;29:1377–88. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17615–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906541106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scita G, Di Fiore PP. The endocytic matrix. Nature. 2010;463:464–73. doi: 10.1038/nature08910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Di Guglielmo GM, Baass PC, Ou WJ, Posner BI, Bergeron JJ. Compartmentalization of SHC, GRB2 and mSOS, and hyprphosphorylation of Raf-1 by EGF but not insulin in liver parenchyma. Embo J. 1994;13:4269–77. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06747.x. The first biochemical evidence that RTK signaling continues from endosomes is reported, demonstrating a complex of activated EGFR, Shc, Grb2, and mSos in the endosomal membrane. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baass PC, Di Guglielmo GM, Authier F, Posner BI, Bergeron JJ. Compartmentalized signal transduction by receptor tyrosine kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:465–70. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vieira AV, Lamaze C, Schmid SL. Control of EGF receptor signaling by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1996;274:2086–9. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2086. The first demonstration that clathrin-mediated endocytosis is required to achieve full EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y, Moheban DB, Conway BR, Bhattacharyya A, Segal RA. Cell surface Trk receptors mediate NGF-induced survival while internalized receptors regulate NGF-induced differentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5671–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05671.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu C, Lai CF, Mobley WC. Nerve growth factor activates persistent Rap1 signaling in endosomes. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5406–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ceresa BP, Kao AW, Santeler SR, Pessin JE. Inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis selectively attenuates specific insulin receptor signal transduction pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3862–70. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y, Pennock SD, Chen X, Kazlauskas A, Wang Z. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-mediated signal transduction from endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8038–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sawamiphak S, et al. Ephrin-B2 regulates VEGFR2 function in developmental and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:487–91. doi: 10.1038/nature08995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Y, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ehlers MD, Kaplan DR, Price DL, Koliatsos VE. NGF-stimulated retrograde transport of trkA in the mammalian nervous system. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:149–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grimes ML, et al. Endocytosis of activated TrkA: evidence that nerve growth factor induces formation of signaling endosomes. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7950–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07950.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watson FL, et al. Neurotrophins use the Erk5 pathway to mediate a retrograde survival response. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:981–8. doi: 10.1038/nn720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Junttila TT, et al. Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scaltriti M, et al. Lapatinib, a HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces stabilization and accumulation of HER2 and potentiates trastuzumab-dependent cell cytotoxicity. Oncogene. 2009;28:803–14. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garrett JT, et al. Transcriptional and posttranslational up-regulation of HER3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016140108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]