Abstract

Questions relevant to DSM-V alcohol use disorders (AUD) include whether dimensional measures provide more information than categorical diagnoses, whether to combine abuse and dependence criteria, and whether to add a new diagnostic criterion, binge drinking. Binary and dimensional models of three versions of AUD criteria were investigated: (1) dependence criteria; (2) abuse and dependence criteria combined; and (3) abuse and dependence criteria combined with a binge drinking criterion added. In a national sample of lifetime drinkers (N = 27,324), these models of AUD criteria were investigated in relation to two well-established risk factors for AUD, family history and early drinking onset. Logistic or Poisson regression modeled the relationships between the validating variables and dependence in categorical, dimensional and hybrid forms; Wald tests were used to assess differences between the dimensional, categorical and hybrid models. Alcohol dependence criteria represented a single continuum (family history Wald = 9.93, p = 0.13; early drinking Wald = 7.62, p = 0.27) with no support for a categorical or hybrid version of alcohol dependence. Adding four abuse criteria produced similar results for family history (Wald = 15.4, p = 0.12) although with early drinking, this model showed a trend towards deviating from the data (Wald = 16.7, p = 0.08). No support was found for any diagnostic threshold at 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7 criteria when abuse and dependence were combined. Adding binge drinking resulted in a significant departure from linearity for family history (Wald = 21.8, p = 0.03) and early drinking (Wald = 23.9, p = 0.01). The number of alcohol dependence and abuse criteria met should be explored further as a useful AUD severity indicator or phenotype.

Keywords: Alcohol use disorders, DSM-IV diagnoses, Dimensional and categorical diagnoses, NESARC

1. Introduction

1.1. Reliable and valid measures

Reliable, valid and maximally informative measures are essential for research. DSM-IV has provided diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders that can be used consistently across disciplines for many purposes. However, research developments and experience with DSM-IV have raised issues about DSM-IV criteria now under consideration regarding DSM-V. These include whether diagnoses should have a dimensional representation, whether disorders with related criteria should be consolidated into single disorders, and whether adding new criteria will improve reliability and validity of a particular diagnosis or its dimensional representation. These issues all apply to DSM-IV alcohol use disorders (AUD).

1.1.1. Issue 1: Dimensional representation

The basis of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria (Rounsaville et al., 1986) was the Alcohol Dependence Syndrome (Edwards and Gross, 1976), a dimensional construct representing impaired control over drinking. In DSM-IV, alcohol dependence is binary, with no provision for a severity indicator. If a given disorder has an inherent severity grading, then etiologic research using dichotomized measures of that disorder based on artificially imposed thresholds will cause loss of potentially important information, increasing the difficulty of identifying etiologic factors. The validity of dimensional representations of many disorders, including alcohol use disorders, are currently under study as additions to DSM-V (Helzer et al., 2006).

1.1.2. Issue 2: Combining highly related disorders

In theory, the ADS is a psychobiological process that leads to impaired control over persistent, heavy drinking. The causes of this impaired control are considered to be different from the causes of drinking consequences such as interpersonal problems (Edwards and Gross, 1976). DSM-IV operationalized dependence and abuse (drinking consequences) as two separate and hierarchical disorders, with dependence taking precedence over abuse if criteria for both are met. However, questions for DSM-V include the validity of the hierarchical division of alcohol disorders into dependence and abuse, and whether the two disorders should be combined or kept separate (Hasin et al., 2006a; Schuckit and Saunders, 2006).

1.1.3. Issue 3: Adding a new criterion

A set of diagnostic criteria lacking important elements will be less sensitive or specific than a set incorporating all relevant elements, and hence, identification and addition of such elements is important. However, there are two important reasons not to add new criteria. The first is the need to keep criteria sets easier to use for clinicians. As has been stated previously, “the optimal criteria are those that are easy to remember and which can be evaluated without exceptional efforts…or they will be ignored in clinical settings” (Schuckit, in Hasin et al., 2003, p. 250). The more criteria included for a diagnosis of a particular disorder, the more difficult the set will be to remember and the more effort will be required in evaluation of the criteria. The second reason is that criteria added without consistent evidence supporting their validity may be invalid. Invalid criteria will reduce the reliability and validity of the entire criteria set, and may introduce unwanted heterogeneity in groups defined by the criteria. Thus, when new criteria are proposed as additions to existing sets, their effect on the psychometric performance of the entire criteria set requires scrutiny. For alcohol use disorders, such a proposed criterion is binge drinking, defined as five or more drinks per occasion at least weekly for men, and four or more drinks for women (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007).

1.2. Different approaches to address psychometric properties

Different approaches have been used to address the psychometric properties of abuse and dependence and the structure and relationship of the criteria to each other (Hasin et al., 2006b; Helzer et al., 2007). These have included test–retest reliability studies, longitudinal studies, factor analyses, latent class analyses (LCA), item response theory (IRT) analyses and mixture modeling.

1.2.1. Test–retest studies

Test–retest reliability studies show whether two conditions differ in their reliability. Many studies showed very good to excellent reliability of alcohol dependence (Hasin et al., 2006a), but the reliability of abuse was often somewhat or substantially lower than dependence, suggesting a distinction between the disorders.

1.2.2. Longitudinal studies

When one disorder is consistently prodromal to a second disorder and the disorders share a similar course, little reason exists to keep the disorders separate. Longitudinal studies of alcohol abuse and dependence consistently indicate that abuse is not consistently prodromal to dependence, and that the course of abuse and dependence differ (Hasin et al., 1990, 1997a,b; Grant et al., 2001; Schuckit et al., 2001, 2008) suggesting that the disorders are distinct.

1.2.3. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) provides initial information on the factor structure of a set of items, while confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) can test whether the correlational structure of a set of criteria matches a hypothesized structure predicted by a conceptual model, e.g., a one-factor model or two-factor model. Several studies of AUD criteria using U.S. samples found significantly better fit for a two-factor model (Harford and Muthen, 2001; Muthen et al., 1993; Muthen, 1995; Grant et al., 2007). These papers did find evidence for slight deviations from the DSM-IV abuse/dependence distinction, which may be expected given differences in distributions of the AUD criteria and other differences between samples. Another study used EFA to guide a CFA comparing two-, three- and four-factor solutions. In this study, the two-factor solution corresponded to dependence and abuse, while the third factor was characterized by tolerance (Grant et al., 2007).

In contrast, Proudfoot et al. (2006) and Martin et al. (2006) found evidence of similar model fit in CFA for one- and two-factor models, preferring the one-factor model on the basis of parsimony and high factor correlations. An earlier paper using a U.S. sample (Hasin et al., 1994) found evidence for a one-factor model, but since the measure consisted of proxy indicators of the Alcohol Dependence Syndrome using a scale of alcohol problems, the results may not be directly comparable. In twin data, an EFA of 110 alcohol symptom items from Feighner criteria (Feighner et al., 1972), RDC (Spitzer et al., 1978), DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), and DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) showed that one factor fit all the items (Krueger et al., 2004). An exploratory factor analyses of NESARC data prior to an IRT study (Saha et al., 2006) showed that a one-factor model was suitable after dropping an abuse item, legal problems due to alcohol; a paper describing a similar EFA in NESARC data prior to a Rasch analysis (Kahler and Strong, 2006) appeared to reflect similar results although these authors did not elect to drop the item with the lowest factor loading from further analyses. These papers thus provide mixed support for one- and two-factor models. Neither EFA nor CFA directly addresses whether a categorical or dimensional model best represents a given condition.

1.2.4. Latent class analysis

Latent class analysis is used to identify homogeneous classes of individuals, and assign individuals to classes. Using COGA study data (Reich et al., 1998), LCA of DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria identified four classes (Bucholz et al., 1996) largely differentiated by successively greater endorsement probabilities for all criteria across classes. In heavy-drinking twins, four classes were preferred for women and five for men using DSM-IV dependence and abuse criteria (Lynskey et al., 2005). In Lynskey et al. (2005), the preferred five-class solution among men identified classes characterized as severely dependent, moderately dependent, heavy drinkers and low/no problem drinkers, with an additional class corresponding to abuse. Members of the abuse class reported comparable drinking patterns for their heaviest drinking period to those in the moderate dependence class and were no less likely to report tolerance to alcohol, yet they had very low probability of meeting criteria for alcohol dependence. Among NESARC participants meeting criteria for current alcohol dependence, LCA indicated a six-class solution for the seven dependence criteria, generally corresponding to the number of criteria endorsed (Moss et al., 2008). In this study, only the most severe classes were related to lifetime alcohol landmarks, but the effect of excluding those below the diagnostic threshold is unclear. Thus, the LCA results generally support the idea of a gradient of severity for alcohol use disorders defined by the number of criteria, with inconsistent results on the presence (Lynskey et al., 2005) or absence (Bucholz et al., 1996) of a separate abuse class.

1.2.5. Rasch model or item response theory analysis

If a unidimensional set of criteria can be identified through factor analysis, the one-parameter Rasch model provides information on the severity level of individual criteria, while the two-parameter item response theory (IRT) model provides information on severity and also criterion discrimination between individuals of differing severities. Rasch and IRT analyses show that abuse and dependence criteria are intermixed on an underlying spectrum of severity (Langenbucher et al., 2004; Kahler and Strong, 2006; Martin et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006) although some analyses required removal of criteria to achieve unidimensionality (Langenbucher et al., 2004; Saha et al., 2006). IRT analyses of alcohol problem scales (as distinct from diagnostic criteria) in various samples have suggested incorporation of consumption indicators into measures of other alcohol problems (Krueger et al., 2004; Kahler et al., 2003). However, to our knowledge, only one paper (Saha et al., 2007) has explicitly addressed adding binge drinking to the DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria among current drinkers. While IRT can address the differential functioning of items in a set by respondent characteristics, it is not designed to address the relationship of the entire criteria set to established risk factors.

1.2.6. Hybrid psychometric models

Hybrid models including latent class factor analysis (LCFA) and factor mixture analysis (FMA) allow incorporation of dimensional and categorical aspects of a criterion set (Muthen, 2006). Among male binge drinkers in the NESARC, use of LCFA for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence suggested four classes and one factor, while a FMA suggested two classes and one factor (Muthen, 2006). In twin data, the FMA model in twin data showed three classes and one factor (Kuo et al., 2008). These models provide solutions that integrate LCA and factor findings. However, the actual diagnostic variables (or phenotypes for genetic studies) provided by these hybrid models are not yet obvious.

1.3. Gaps in knowledge

These studies provide information about gradations in the severity of AUD criteria, but not on whether dimensionality is found only after the diagnostic threshold has been exceeded (the Muthen paper used a threshold defined by binge drinking rather than diagnostic criteria, and did not include those under this threshold in the sample). The studies show support for combining abuse and dependence albeit with some evidence to the contrary and no information on what a diagnostic threshold might be if the alcohol abuse and dependence criteria were combined. Thus far, the literature provides little information about whether to add binge drinking to the criteria set. We therefore extended a statistical method used previously (Kendler and Gardner, 1998; Hasin et al., 2006b), which we call the “discontinuity approach” to examine these issues.

1.4. The discontinuity approach

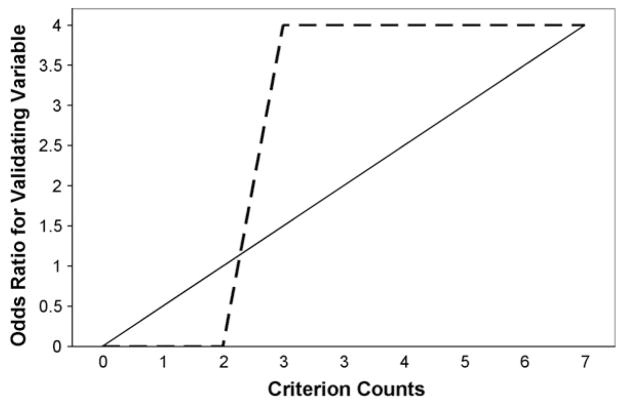

The discontinuity approach directly incorporates the relationship of an observed criterion set to important external validating variables. It rests on two assumptions. (1) Cases and non-cases of an inherently categorical illness or condition will be differentiated at the diagnostic threshold through clear discontinuities in the strength of association between the number of criteria and risk factors. (2) Strength of association between the number of criteria and risk factors will be homogeneous within groups of cases and non-cases, i.e., within-group slopes of regression lines representing associations between number of criteria and risk factors are zero. Fig. 1 shows a hypothetical representation of the relationship of the criteria to a risk factor in a categorical model, as well as in a model in which the association with a risk factor increases linearly with the number of criteria met.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical models for DSM-IV alcohol dependence: linear model of criterion count (solid line) and two homogenous groups dichotomized by threshold at 3 criteria (dashed line).

The discontinuity approach can address all three issues raised above: dimension versus binary condition, relationship of the criteria of similar disorders (abuse and dependence), and addition of new criteria (binge drinking). We previously used the method to examine the seven criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence among current drinkers, finding that these criteria related to risk factors in a monotonic fashion, with no support for any putative model of alcohol dependence that included a category (Hasin et al., 2006b). However, lifetime criteria evaluated among lifetime drinkers are required for some types of research, especially genetic studies. For this reason, and to contribute to a greater overall understanding of AUD criteria as preparations for DSM-V are underway, we now extend this approach to study lifetime criteria for alcohol dependence, abuse and binge drinking among lifetime drinkers from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) sample.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

The 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is based on a United States representative sample, as described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004). The target population included those residing in households and group quarters, 18 years and older. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by professional interviewers with 43,093 respondents. The survey response rate was 81%. Blacks, Hispanics, and young adults (ages 18–24) were over-sampled, with data adjusted for over-sampling and non-response. The weighted data were then adjusted to represent the U.S. civilian population based on the 2000 Census. Field methods included extensive home study and structured in-person training, supervision, and quality control (Grant et al., 2005, 2006a,b). In this report, we included lifetime drinkers, i.e., those who ever drank at least 12 drinks during a one-year period, N = 27,324. Of these, 62.9% were white, 16.5% African-American, 16.7% Hispanic, 52.4% male and the mean age was 45.1 years (S.D. 16.8).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. DSM-IV diagnostic interview

The diagnostic interview was the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) (Grant et al., 2003). Computer diagnostic programs implemented the DSM-IV criteria for the disorders using AUDADIS-IV data.

2.2.2. Alcohol abuse and dependence criteria

Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence. The seven alcohol dependence criteria included (1) tolerance; (2) withdrawal or withdrawal avoidance; (3) persistent desire/unsuccessful attempts to reduce drinking; (4) time drinking or recovering from its effects; (5) giving up or reducing occupational, social and/or recreational activities to drink; (6) impaired control; and (7) continued drinking despite physical or psychological problems. The four alcohol abuse criteria included (1) failure to fulfill major role obligations; (2) recurrent hazardous use; (3) recurrent substance-related legal problems; and (4) continued drinking despite persistent social or interpersonal problems. Unlike diagnostic measures that skip questions on dependence criteria if no abuse criteria were met (Hasin and Grant, 2004), the AUDADIS completely covers DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence among all respondents that were ever drinkers. Reliability of AUDADIS-IV alcohol diagnoses ranged from good to excellent in clinical and general population samples (K = 0.70–0.84) (Grant et al., 1995, 2003; Chatterji et al., 1997; Hasin et al., 1997a,b); and many validation methods show that AUDADIS-IV alcohol use disorder diagnoses and criteria have good to excellent validity (Hasin et al., 1996, 1997a,b, 1994; Hasin and Paykin, 1999; Nelson et al., 1999; Cottler et al., 1997; Pull et al., 1997; Harford and Grant, 1994), including psychiatrist reappraisals (Canino et al., 1999).

2.2.3. Binge drinking

The lifetime binge drinking variable was created from positive responses on either of two measures in the AUDADIS-IV, derived from the period of heaviest drinking (past or last 12 months): (1) usual consumption of 5+ drinks (men) or 4+ drinks (women) at least weekly; and (2) largest amount consumed 5+ drinks (men) or 4+ drinks (women) at least weekly. This is consistent with previous reports (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007) and the NIAAA Clinicians Guide (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse, 2005). Among NESARC respondents, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were good to excellent (ICC = 0.69–0.84) for overall frequency of alcohol consumption, as well as usual and largest quantity of drinks (Grant et al., 2003).

2.2.4. Validating variables

Validating variables were used to examine discontinuities at putative boundaries in risk factor levels, and within-group slopes of regression lines. Two validating variables were used: (1) family history of alcohol problems, and (2) early age of onset of drinking alcohol. To assess family history of alcoholism, respondents were asked about relatives by relative class, prompted by definitions consisting of observable manifestations of AUD criteria (Heiman et al., 2008) to improve sensitivity (Andreasen et al., 1977; Slutske et al., 1996; Zimmerman et al., 1988). A family history variable was created to represent the proportion of parents and siblings of each respondent with an alcohol problem. AUDADIS family history measures have good to excellent test–retest reliability, with kappas >0.70 for fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters (Grant and Dawson, 1997). Early onset of drinking excluding tastes or sips was dichotomized at 14 years or younger versus others, a difference that substantially increases the risk of alcohol use disorders (Grant et al., 2001, 2006a,b; Grant and Dawson, 1997; Prescott and Kendler, 1999). Age of onset of alcohol consumption has good to excellent reliability (Grant et al., 1995).

2.3. Statistical analyses

2.3.1. Regression models in weighted data

Analyses were conducted with three sets of lifetime criteria: (1) alcohol dependence only (range, 0–7); (2) alcohol dependence and abuse (range, 0–11); and (3) alcohol dependence, abuse and binge drinking (range, 0–12). To determine the association between the criteria set and family history, Poisson regression models were used, with the outcome log((EY)/N), where Y is the count of affected relatives and N is the total number of relatives in each family. Early onset of drinking (a binary variable) was modeled using logistic regression. Due to the complex sample design of the NESARC, SUDAAN was used to apply these models. SUDAAN calculates correct estimates of the standard errors in complex survey designs via Taylor linearization. Models were all adjusted for age, gender and race.

2.3.2. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence criteria

As former drinkers may differ from current drinkers in many ways, we began by testing whether our results on categorical and dimensional models of the seven lifetime dependence criteria among current drinkers (Hasin et al., 2006a,b) applied to the broader sample of lifetime drinkers. We did this with a basic model (Model 1) with 10 predictors (M7Dum): the 3 control variables and 7 non-ordered dummy variables to represent the seven levels of severity (1–7) of the alcohol-dependence criteria. Persons with no alcohol dependence criteria constituted the reference group. Persons with one dependence criterion were compared to the reference group, as were persons with two dependence criteria, etc., up to persons with seven dependence criteria. Dummy variables were used at this stage to avoid advance assumptions about a trend. The seven parameters (β1, β2, …, β7) associated with the dummy variables indicate the effect of the number of alcohol dependence criteria. Consistently increasing regression coefficients for dummy variables that can be indicated by a line (slope) would suggest an underlying dimensional variable in a more parsimonious model with a single parameter representing the slope (indicating linearity). Model 1 provides a basis for comparison with models using different forms of alcohol dependence as the predictor that involve a boundary. To test whether a linear trend represented the effect of criteria count on an outcome, we used Model 2 (MDimensional) to test for a dimensional trend in criteria count. Instead of seven dummy variables, one predictor was used to represent dependence criteria as a single dimensional measure (i.e., 0–7 criteria) in which the associated parameter β could be used to indicate a trend in the effect of criterion count. In addition to Model 1 (M7Dum) and Model 2 (MDimensional), we used two other models to explore patterns in the relationship between the number of criteria and the validating variables. Model 3 (MThreshtrend) used a binary variable contrasting 0–2 criteria versus 3 or more, and a single dimensional variable for 3–7 criteria. The lack of a dimensional variable for 0–2 criteria would illustrate the possibility of homogeneity (lack of slope) within this category, but not above the threshold of three criteria, the diagnostic threshold. Model 4 (MDSM-IV) consisted of a single variable contrasting 0–2 criteria versus 3 or more, the DSM-IV dichotomous diagnosis, with homogeneity (zero slope) within the two categories defined by the threshold.

To compare the models incorporating the weights reflecting the complex sample design, the Wald test was used to test hypotheses on the model parameters. (While differences in the fit of nested models are often compared using the likelihood ratio test, this test cannot be used with weighted data, which is the nature of NESARC data due to the complex sample design.) We used the Wald statistic to determine whether alternative parameterizations of the association between the validating variable and the number of dependence criteria produce significantly different estimates between Model 1 and Model 2, with a single linear predictor (i.e., (β1, β2, …, β7) compared with (1β, 2β, …, 7β)). The Wald test statistic is calculated using the squared distance between two vectors of estimated effects in the two nested models. Similar to the likelihood ratio test, it follows a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom defined as the difference in the number of parameters in two nested models. With large samples such as the NESARC, the likelihood ratio test and Wald test are generally equivalent in testing the hypotheses on model parameters for the pattern in the association between outcome and predictors if no sampling weights applied (Pawitan, 2001). Little or no difference between the dummy variable model and the linear model would indicate support for the use of Model 2, as it is most parsimonious in terms of number of parameters. The Wald test was also used to explore differences in patterns of associations between the number of dependence criteria and the validating variables described by Model 1 and the alternative models (Models 3 and 4). Following our previous methods, we considered that Model 2 ‘fit’ the pattern in Model 1 better than Model 4 (for example) if the difference between Models 1 and 2 were small (non-significant), while the difference between Models 1 and 4 were not small (e.g., significantly different). For all tests, statistical significance was set at 0.05.

2.3.3. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence and abuse criteria

The dummy variable model (M11Dum) or Model A, representing levels of severity (range 0–11) was compared with Model B (M11Dimensional), which used a continuous dimensional measure of criteria (range 0–11). Since the discontinuity method allows testing for dichotomies in the data, we also tested binary diagnostic models with thresholds at 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 criteria. An observed dichotomy would argue for the use of a specific diagnostic threshold in the combined abuse and dependence criteria.

2.3.4. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence, abuse and binge drinking criteria

Given our results for the combination of dependence and abuse criteria (below), we analyzed only Models 1 and 2 using the same validating variables. The variables were generated as described above, using a dummy variable model with seven dependence, four abuse, and a binge-drinking criterion. Model C (M12Dum) contained 12 dummy variables and Model D (M12Dimensional) contained a single indicator of criteria counts with values ranging from 0 to 12. Model C (M12Dum) was compared to Model D (M12Dimensional).

2.3.5. Testing the dummy variable model

Prior to conducting these analyses, we used the Wald statistic to test whether the set of dummy variables in Model 1 (M7Dum), Model A (M11Dum) and Model C (M12Dum) were associated with each of the validating variables. For example, the null hypothesis on the parameters of Model 1 was (β1, β2, …, β7) = (0, 0, …, 0) for no association between the alcohol dependence criteria count and the validating variable, adjusting for age, gender and race. The null hypotheses were all rejected (all p-values <0.0001).

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence

The prevalence of each criterion is shown in Table 1. Using larger or longer than intended (a dependence criterion) and hazardous use (an abuse criterion) had the highest weighted prevalence. Giving up activities to drink (a dependence criterion) and neglecting social roles because of drinking (an abuse criterion) had the lowest prevalence. Only one criterion was reported by 14.8% of the sample, while 1.3% experienced all 12 (Table 2). Therefore, observed linearity in the dimensional variable representing criteria counts was not a function of equal frequencies across the categorical variables.

Table 1.

Prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria and weekly binge drinking in NESARC lifetime drinkers (N = 27,324).

| Alcohol criterion | Prevalence, %a (n) |

|---|---|

| Abuse | |

| Neglect roles | 6.4 (1658) |

| Hazardous use | 39.4 (10067) |

| Legal problems | 10.4 (2704) |

| Social/interpersonal problems | 15.6 (4018) |

| Dependence | |

| Tolerance | 33.8 (8818) |

| Withdrawal | 23.9 (6321) |

| Larger/longer | 39.4 (10230) |

| Quit/control | 33.5 (9131) |

| Time spent | 17.8 (4673) |

| Activities given up | 5.1 (1350) |

| Physical/psychological problems | 15.4 (4046) |

| Exceeded drinking limits weekly b | 35.8 (8922) |

Weighted percents taking into account the weighted sample.

Using least 4+ for women and 5+ for men at least once a week.

Table 2.

Distribution of NESARC participants having from 0 to 12 criteria including alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse and weekly binge drinkingb criteria (N = 27,324).

| Number of criteria | Prevalence, %a (n) | Cumulative prevalence, %a (n) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 32.9 (9457) | 32.9 (9457) |

| 1 | 14.8 (4071) | 47.7 (13528) |

| 2 | 11.2 (3054) | 59.0 (16582) |

| 3 | 9.3 (2472) | 68.2 (19054) |

| 4 | 7.4 (1956) | 75.6 (21010) |

| 5 | 6.0 (1609) | 81.6 (22619) |

| 6 | 4.6 (1174) | 86.2 (23793) |

| 7 | 3.7 (945) | 89.9 (24738) |

| 8 | 3.0 (760) | 92.9 (25498) |

| 9 | 2.4 (627) | 95.3 (26125) |

| 10 | 1.7 (433) | 97.0 (26558) |

| 11 | 1.7 (430) | 98.7 (26988) |

| 12 | 1.3 (336) | 100.0 (27324) |

Weighted percents taking into account the weighted sample.

Using 4+ for women and 5+ for men at least once a week.

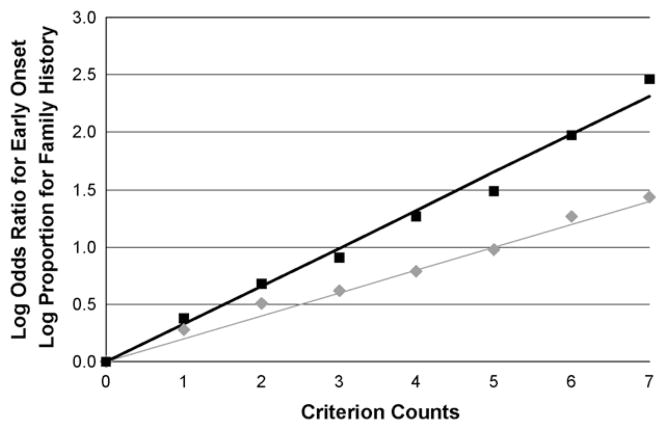

3.2. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence criteria

The log proportions for family history were plotted against the seven dummy variables representing criterion counts (M7Dum) to show the relationship between the number of criteria and the validating variable (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 shows that the data points lie close to the line. Comparing these points to the plotted line representing the continuous dimensional model (M7Dimensional) with a slope coefficient of 0.20 (S.E. = 0.01) showed no significant difference between the two parameterizations of the criteria with family history (Wald = 9.93, p = 0.13). Similar results were seen for the effects of M7Dum and M7Dimensional on early drinking onset (Fig. 2). The M7Dimensional model had a slope coefficient of 0.33 (S.E. = 0.01). This and the dummy models did not differ significantly (Wald = 7.62, p = 0.27). In contrast, the binary diagnostic model differed significantly from the dummy models (family history Wald = 126.1, p = 0.00; early onset Wald = 358.1, p = 0.00). The hybrid model allowing for homogeneity (zero slope) below 3 criteria and dimensionality at and above 3 criteria also differed significantly from the dummy variable model (family history Wald = 48.3, p = 0.00; early onset Wald = 244.2, p = 0.00). These results confirmed that in lifetime as well as in current drinkers, an underlying severity continuum better explained the relationship between the number of criteria for alcohol dependence and these two validating variables than a model incorporating categories, either above and below the diagnostic threshold, or only below the diagnostic threshold.

Fig. 2.

Model 1 (M7Dum) versus Model 2 (MDimensional) (Model 1 results shown in symbols; Model 2 by lines).

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

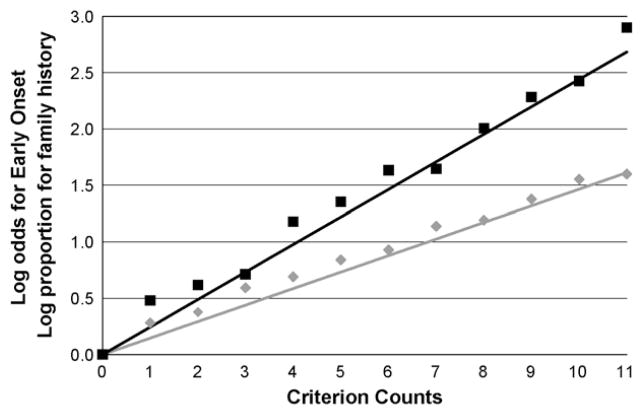

3.3. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence and abuse criteria

We examined abuse and dependence as a single continuum of severity using Model A (M11Dum) and Model B (M11Dimensional) (Fig. 3). While the data points around the line representing linearity were visually more distant from the line than the data points around the line in Fig. 1, the Wald tests indicated that Models A and B did not differ significantly whether family history was used as the validator (Wald = 15.4, p = 0.12) and showed results at the trend level only when early drinking onset was used as the validator (Wald = 16.7, p = 0.08; Table 3). The slope coefficient for Model B (M11Dimensional) was 0.15 (S.E. = 0.00) for family history and 0.24 (S.E. = 0.01) for early drinking onset. The results for these two validators therefore suggest a linearly increasing relationship between the number of abuse and dependence criteria and a positive family history, with more equivocal results when early drinking onset was used as the validator.

Fig. 3.

Model A (M11Dum) versus Model B (M11Dimensional) for 11 criteria including dependence and abuse (Model A results shown in symbols; Model B by lines).

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

Table 3.

Comparison of the dummy variable model (Model A) to the dimensional model (Model B), representing 11 alcohol dependence and abuse criteria in NESARC participants (N = 27,324).

| Outcome | Criterion count (K) | Model A estimate (M11Dum) | Model B estimate (M11Dimensional) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| log P(K)/P(0) | |||

| Family history | 1 | 0.28 (0.05) | 0.15 (0.00) |

| 2 | 0.38 (0.05) | 0.29 (0.01) | |

| 3 | 0.59 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.01) | |

| 4 | 0.69 (0.06) | 0.59 (0.02) | |

| 5 | 0.84 (0.07) | 0.73 (0.02) | |

| 6 | 0.93 (0.06) | 0.88 (0.03) | |

| 7 | 1.14 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.03) | |

| 8 | 1.19 (0.07) | 1.17 (0.04) | |

| 9 | 1.38 (0.08) | 1.32 (0.04) | |

| 10 | 1.55 (0.08) | 1.47 (0.04) | |

| 11 | 1.60 (0.07) | 1.61 (0.05) | |

| p-value for test of difference with Model 1 | 0.12 | ||

| Outcome | Criterion count (K) | Model A estimate (M11Dum) | Model B estimate (M11Dimensional) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| log(Odds(K)/Odds(0)) | |||

| Age of onset | 1 | 0.48 (0.11) | 0.24 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.62 (0.10) | 0.49 (0.02) | |

| 3 | 0.71 (0.13) | 0.73 (0.03) | |

| 4 | 1.18 (0.12) | 0.98 (0.03) | |

| 5 | 1.35 (0.13) | 1.22 (0.04) | |

| 6 | 1.63 (0.12) | 1.46 (0.05) | |

| 7 | 1.65 (0.14) | 1.71 (0.06) | |

| 8 | 2.01 (0.14) | 1.95 (0.07) | |

| 9 | 2.28 (0.15) | 2.20 (0.08) | |

| 10 | 2.43 (0.14) | 2.44 (0.09) | |

| 11 | 2.90 (0.15) | 2.69 (0.10) | |

| p-value for test of difference with Model 1 | 0.08 | ||

Although these results provided no evidence of a diagnostic threshold, we tested binary models against Model A for thresholds at 3, 4, 5, 6 or 7 criteria since this information could be of use for DSM-V decision-making. No evidence was found that binary models with any of these thresholds fit the data well (all Wald tests of binary versus dummy models, p < 0.0001).

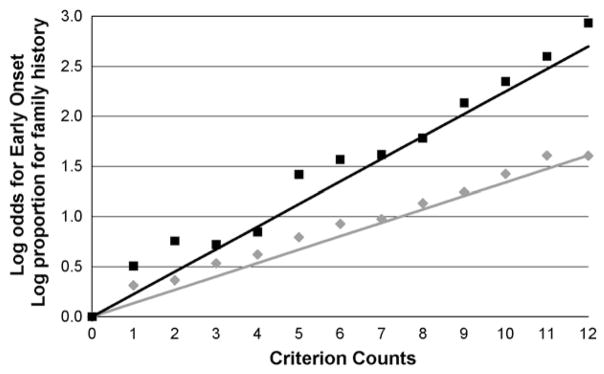

3.4. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol dependence, abuse and binge drinking criteria

We next examined dependence criteria, abuse criteria and binge drinking as a single continuum of severity. The relationships of these 12 putative criteria (M12Dum) to family history and early drinking onset are shown in Fig. 4. The data points around the line representing linearity were visually further from the line than the data points around the line in Fig. 2. In this case, the continuous, linear model did differ significantly from the dummy variable models for family history (Wald = 21.8, p = 0.03) and early drinking onset (Wald = 23.9, p = 0.01) (Table 4). Thus, as shown in Fig. 4 and the results of the Wald tests, adding binge drinking to the set of criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence introduced sufficient variability around the continuous line at a number of points on the line that the Wald test indicated significant non-linearity.

Fig. 4.

Model C (M12Dum) versus Model D (M12Dimensional) for 12 criteria including dependence, abuse and binge drinking defined as least 4+/5+ at least once a week (Model C results shown in symbols; Model D by lines).

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

family history, ■ onset of drinking before age 15 years.

Table 4.

Comparison of the dummy variable model (Model C) to the dimensional model (Model D) representing 12 alcohol dependence, abuse and weekly binge drinking criteria in NESARC participants (N = 27,324).

| Outcome | Criterion count (K) | Model C estimate (M12Dum) | Model D estimate (M12Dimensional) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| log P(K)/P(0) | |||

| Family history | 1 | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.13 (0.00) |

| 2 | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.27 (0.01) | |

| 3 | 0.53 (0.05) | 0.40 (0.01) | |

| 4 | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.54 (0.02) | |

| 5 | 0.80 (0.06) | 0.67 (0.02) | |

| 6 | 0.93 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.02) | |

| 7 | 0.98 (0.07) | 0.94 (0.03) | |

| 8 | 1.13 (0.07) | 1.07 (0.03) | |

| 9 | 1.24 (0.07) | 1.21 (0.04) | |

| 10 | 1.42 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.04) | |

| 11 | 1.61 (0.08) | 1.47 (0.04) | |

| 12 | 1.61 (0.08) | 1.61 (0.05) | |

| p-value for test of difference with Model 1 | 0.03 | ||

| Outcome | Criterion count (K) | Model C estimate (M12Dum) | Model D estimate (M12Dimensional) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| log(Odds(K)/Odds(0)) | |||

| Age of onset | 1 | 0.51 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.01) |

| 2 | 0.76 (0.11) | 0.45 (0.02) | |

| 3 | 0.72 (0.12) | 0.67 (0.02) | |

| 4 | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.90 (0.03) | |

| 5 | 1.42 (0.12) | 1.12 (0.04) | |

| 6 | 1.57 (0.13) | 1.35 (0.05) | |

| 7 | 1.62 (0.12) | 1.57 (0.06) | |

| 8 | 1.78 (0.15) | 1.80 (0.06) | |

| 9 | 2.13 (0.14) | 2.02 (0.07) | |

| 10 | 2.35 (0.16) | 2.25 (0.08) | |

| 11 | 2.60 (0.13) | 2.47 (0.09) | |

| 12 | 2.93 (0.16) | 2.70 (0.10) | |

| p-value for test of difference with Model 1 | 0.01 | ||

4. Discussion

Using the discontinuity approach, the results indicated that in lifetime drinkers, DSM-IV lifetime alcohol dependence criteria can be used to represent a linearly increasing continuum of liability using as validators two important risk factors for alcohol use disorders, family history of alcoholism and early age of drinking onset. In addition, a similar linear relationship was found for alcohol abuse and dependence combined, albeit with firmer support when family history was used as the validator than when early drinking onset was used. These results add to evidence suggesting that alcohol abuse and dependence criteria are intermixed and lie on a single underlying continuum. However, in contrast, no support was found for a model including categories either below the DSM-IV diagnostic threshold for alcohol dependence criteria at the present DSM-IV threshold, or for alcohol dependence and abuse criteria at any of several thresholds.

In contrast to the above results, adding a dichotomous lifetime 4+/5+ binge drinking criterion resulted in a significant departure from fit of the model to the data. These results are inconsistent with IRT findings on current (last 12 months) criteria (Saha et al., 2007) suggesting that such a binge drinking criterion could be added. Two reasons may explain the discrepancy in findings. One reason is that the IRT methodology examines criteria only in relation to each other, while the discontinuity approach not only examines the criteria in relation to each other, but also directly incorporates information from external validators. The other reason is that the discontinuity results for lifetime binge drinking may differ from IRT findings due to the difference in time frame. For example, our analyses included some lifetime binge drinkers who were abstainers in the last 12 months as part of recovery from alcohol dependence (Dawson et al., 2005). Such individuals would have been omitted entirely from Saha et al. (2007). In either case, the difference in findings across the two methods suggests caution in the addition of binge drinking as a criterion to the AUD criteria, since different methods and timeframes should produce consistent results to provide sufficiently strong support to add a new criterion to the existing criteria set in DSM-V.

The discontinuity approach differs from CFA, LCA and IRT or Rasch model analysis in several fundamental ways. First, the discontinuity approach is based on the number of criteria endorsed and not on the properties of the individual items. Second, the approach directly incorporates validation of the criteria set through study of their relationship to key validators (factors well known to be related to the diagnoses but not included in the criteria set). Third, the approach allows for adjustment for important covariates, a feature not available in latent class or IRT analysis. Fourth, the method addresses observed rather than latent variables. Further, the discontinuity approach has been described as advantageous since it avoids the assumptions required of LCA and IRT that are not always met in practice (Helzer et al., 2007). Thus, the discontinuity approach offers the advantage of an additional methodology in evaluating alterations to existing sets of diagnostic criteria.

Two genetic association studies provide a useful illustration of the utility of the additional information provided by a dimensional indicator of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria like Model 2 (M7Dimensional) compared to the binary diagnosis with its arbitrary threshold. Both studies addressed the same allelic variant, and analyses in both studies faced a situation in which statistical power was limited, in one case because the allele of interest was rare (Heath et al., 2001) and the other case because the allele of interest was not rare but the sample was small (Hasin et al., 2002). In both studies, the relationship between a binary diagnosis of DSM-IV alcohol dependence and the allele of interest was in the predicted direction but not statistically significant. However, when dependence was used as a dimensional variable (range 0–7), the predicted relationships between the allele and dependence became significant. These results can be seen as an additional external validation of the dimensional approach to alcohol dependence, in this case, using a biological validator, and support the use of a dimensional approach in other situations of interest where power is limited, e.g., in testing gene × gene or gene × environment interactions. To our knowledge, studies of the 11-criterion continuous measure including abuse and dependence in relation to specific genetic variants have not yet been conducted. These would be informative about the validity of this continuous construct of alcohol use disorders. If validated in genetic studies, such a quantitative variable has the potential to improve the power of genetic studies.

The lack of any evidence for a diagnostic threshold if the alcohol abuse and dependence criteria are combined in DSM-V indicates that a decision regarding a diagnostic threshold will be difficult to make. This problem will need to be overcome if the abuse and dependence criteria are combined, since DSM-V will continue to require diagnostic thresholds. The method of resolving this problem (aside from an arbitrary decision) is not obvious. An alternative solution that avoids the need for a new diagnosis and threshold, while addressing the need to note both abuse and dependence criteria, is to retain both disorders but remove the DSM-IV hierarchical structure requiring that abuse not be diagnosed if dependence criteria are met. Such a decision would also address the fact that women and minority groups differ in their likelihood that alcohol dependence is accompanied by abuse (Hasin and Grant, 2004) and remove confusion about whether to make a dependence diagnosis condition on meeting criteria for abuse (Grant et al., 2007).

Some investigators prefer a focus on the current (or last 12 month) timeframe than the lifetime timeframe on the grounds that recent events are more likely to be recalled and reported than more temporally distant events. We agree with these concerns about reporting and recall. However, the diagnostic criteria need to work well in both current and lifetime timeframes, as the latter is the timeframe for most genetics studies, and for many epidemiologic purposes as well. In fact, assessing a history of past disorders is also commonly part of a clinical evaluation. Despite potential difficulties of recall, the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria have been shown to have excellent reliability and validity in both current and lifetime timeframes under a number of paradigms, including the discontinuity approach results shown above. Therefore, all-encompassing concerns about the lifetime timeframe are misplaced in this regard. It is when one moves from the DSM-IV dependence diagnostic criteria to the proposed revisions that incorporate the aggregation of dependence, abuse and binge drinking that problems begin to arise. For this reason, we suggest caution in incorporating these criteria together in a DSM-V alcohol use disorders category.

Our concerns about binge drinking are not specific to binge drinking per se but would pertain to the proposal of any new criterion. A criterion should have consistent evidence supporting its addition across studies with different designs. We focused on binge drinking because this alcohol-related behavior has already received attention as a proposed new criterion (Saha et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007). We used the discontinuity approach to investigate binge drinking due to our results on the relative fit of different models of dependence to the NESARC data when only seven DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria were examined (above and Hasin et al., 2006a,b). We reasoned that the excellent fit of the model to the data for the seven criteria should be maintained with additional criteria if they were valid. Further, if DSM-V severity measures can be based on the diagnostic criteria, then clinicians can assess severity more efficiently than if assessment of different conditions is required (First, 2005, p. 563). We therefore considered binge drinking in that context. Addition of binge drinking as a criterion resulted in a significant departure from a linear model, suggesting caution in adding it to the existing criterion set for alcohol use disorders.

Study limitations are noted. First, consistent with other epidemiologic studies, dependence and abuse symptoms were measured via retrospective structured self-report rather than observation, as was family history and early drinking onset. However, all variables had good to excellent test–retest reliability and the measures of alcohol use disorders have been validated in many paradigms, including psychiatrist reappraisal (Canino et al., 1999). Also, to reduce misclassification, we created the binge drinking variable from frequency and quantity indicators instead of questions specifically asking about these particular quantities. The focus on observed rather than latent variables could be seen as a limitation, since this method does not attempt to remove measurement error. However, results based on observed variables that appear clear and strong can add to what is known on a specific research question. Other strengths of the work include a focus on lifetime rather than current variables, a timeframe that is important for epi-demiologic and genetic studies, use of a method that does not make some of the assumptions of other methods (Helzer et al., 2007), and direct incorporation of important and well-established risk factors into evaluation of the different patterns of criteria we examined.

Our study evaluated the dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse and dependence criteria to provide information for DSM-V, and for purposes of refining variables for use in genetics and epidemiologic studies. A useful quantitative phenotype should be correlated with diagnosis and also represent severity of a disease (Almasy, 2003). Using validating variables such as age of drinking onset or family history gives meaningful context because they reflect susceptibility (Almasy, 2003). An advantage to using such a quantitative measure (as compared to other severity indicators that may not be assessed in a standardized way from study to study) is the potential for reproducibility across studies that have already assessed all DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria. Our results suggest potential value in exploring a combined quantitative indicator including dependence and abuse criteria in genetic analyses. Finally, the results contribute information based on a different approach to what is known about the performance of alcohol abuse, dependence and binge drinking as criteria for alcohol use disorders in DSM-V. As the present period is one in which convergent information across multiple studies and methods is actively sought by the DSM-V Substance Use Disorders Workgroup, the results are timely.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Valerie Richmond, MA, for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation.

Role of funding sources: This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (K05 AA014223, Hasin) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1 DA018652, Hasin), and support from New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: Author Hasin designed the study, managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Author Beseler undertook the statistical analysis. Both authors wrote sections of the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Almasy L. Quantitative risk factors as indices of alcoholism susceptibility. Ann Med. 2003;35:337–343. doi: 10.1080/07853890310004903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Author; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Author; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N, Endicott J, Spitzer R, Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz K, Heath AC, Reich T, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Schuckit MA. Can we subtype alcoholism? A latent class analysis of data from relatives of alcoholics in a multicenter family study of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1462–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Febo VE, Rubio-Stipec M, Fernandez RL, Hasin D. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:171–185. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, Mavreas V, Pull C, Hasin D, Compton WM, Rubio-Stipec M, Mager D. Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction. 2005;100:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross M. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. Br Med J. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750190059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthen BO, Hsiao-Ye YE, Hasin DS, Stinson FS. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Smith S, Saha TD, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Smith S, Huang B, Saha TD. The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006a;67:363–374. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, True WR, Bucholz KK. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006b;36:109–118. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford T, Grant BF. Prevalence and population validity of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence: the 1989 National Longitudinal Survey on Youth. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Muthen BO. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: a multivariate analysis of DSM-IV symptom items in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:150–157. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Aharonovich E, Liu X, Mamman Z, Matseoane K, Carr L, Li TK. Alcohol and ADH2 in Israel: Ashkenazis, Sephardics, and recent Russian immigrants. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1432–1434. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997b;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:891–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant B, Endicott J. The natural history of alcohol abuse: implications for definitions of alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1537–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006a;101:59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Li Q, McCloud S, Endicott J. Agreement between DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol diagnoses in U. S. community-sample heavy drinkers. Addiction. 1996;91:1517–1527. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9110151710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychol Med. 2006b;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Muthen B, Wisnicki KS, Grant B. Validity of the bi-axial dependence concept: a test in the US general population. Addiction. 1994;89:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: concurrent validity in a nationally representative sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: validity in community sample heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997a;21:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath A, Whitfield JB, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, Slutske WS, Bierut LJ, Statham DB, Martin NG. Towards a molecular epidemiology of alcohol dependence: analysing the interplay of genetic and environmental risk factors. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;40:s33–s40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman GA, Ogburn E, Gorroochurn P, Keyes KM, Hasin D. Evidence for a two-stage model of dependence using the NESARC and its implications for genetic association studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Bucholz KK, Gossop M. A dimensional option for the diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM-V. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16:S24–S33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, van den Brink W, Guth SE. Should there be both categorical and dimensional criteria for the substance use disorders in DSM-V? Addiction. 2006;101:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C, Strong D. A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Stuart GL, Moore TM, Ramsey SE. Item functioning of the alcohol dependence scale in a high-risk sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R, Nichol PE, Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Using latent trait modeling to conceptualize an alcohol problems continuum. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:107–119. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Gardner CJ. Boundaries of major depression: an evaluation of DSM-IV criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:172–177. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo PH, Aggen SH, Prescott CA, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Using a factor mixture modeling approach in alcohol dependence in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Hewitt BG, Grant BF. The Alcohol Dependence Syndrome, 30 years later: a commentary. Addiction. 2007;102:1522–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey M, Nelson EC, Neuman RJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Knopik VS, Slutske W, Whitfield JB, Martin NG, Heath AC. Limitations of DSM-IV operationalizations of alcohol abuse and dependence in a sample of Australian twins. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005;8:574–584. doi: 10.1375/183242705774860178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. DSM-IV criteria endorsement patterns in alcohol dependence: relationship to severity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:306–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Grant B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: factor analysis of DSM-III-R and proposed DSM-IV criteria in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey. Addiction. 1993;88:1079–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO. Factor analysis of alcohol abuse and dependence symptom items in the 1988 National Health Interview survey. Addiction. 1995;90:637–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction. 2006;101:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Accessed January 8, 2008];Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. 2005 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- Nelson CB, Rehm J, Ustun B, Grant BF, Chatterji S. Factor structure of DSM-IV substance disorder criteria endorsed by alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate users: results from the World Health Organization Reliability and Validity Study. Addiction. 1999;94:843–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y. In All Likelihood: Statistical Modeling and Inference Using Likelihood. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of male twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:34–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot H, Baillie AJ, Teesson M. The structure of alcohol dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, Cottler LB, Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blaine J, Mager D, Ustun BT. Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Williams JT, Rice JP, van Eerdewegh P, Foroud T, Hesselbrock V, Schuckit MA, Bucholz K, Porjesz B, Li TK, Conneally PM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Tischfield JA, Crowe RR, Cloninger CR, Wu W, Shears S, Carr K, Crose C, Willig C, Begleiter H. Genome-wide search for genes affecting the risk for alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet. 1998;88:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Proposed changes in DSM-III substance use disorders: description and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:463–468. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha T, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha T, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Saunders JB. The empirical basis of substance use disorders diagnosis: research recommendations for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) Addiction. 2006;101:170–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M, Smith TL, Danko GP, Bucholz KK, Reich T, Bierut L. Five-year clinical course associated with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence in a large group of men and women. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1084–1090. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Danko GP, Smith TL, Bierut LJ, Bucholz KK, Edenberg HJ, Hesselbrock V, Kramer J, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Trim R, Allen R, Kreikebaum S, Hinga B. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, Dunne MP, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Reliability and reporting biases for perceived parental history of alcohol-related problems: agreement between twins and differences between discordant pairs. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:387–395. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Coryell W, Pfohl B, Strangl D. The reliability of the family history method for psychiatric diagnoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:320–322. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800280030004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]