Abstract

Background

Previous studies suggest that alcohol-use disorder severity, defined by the number of criteria met, provides a more informative phenotype than dichotomized DSM-IV diagnostic measures of alcohol use disorders. Therefore, this study examined whether alcohol-use disorder severity predicted first-incident depressive disorders, an association that has never been found for the presence or absence of an alcohol use disorder in the general population.

Method

In a national sample of persons who had never experienced a major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia, manic or hypomanic episode (n=27 571), we examined whether a version of DSM-5 alcohol-use disorder severity (a count of three abuse and all seven dependence criteria) linearly predicted first-incident depressive disorders (MDD or dysthymia) after 3-year follow-up. Wald tests were used to assess whether more complicated models defined the relationship more accurately.

Results

First-incidence of depressive disorders varied across alcohol-use disorder severity and was 4.20% in persons meeting no alcohol-use disorder criteria versus 44.47% in persons meeting all 10 criteria. Alcohol-use disorder severity significantly predicted first-incidence of depressive disorders in a linear fashion (odds ratio 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.22), even after adjustment for sociodemographics, smoking status and predisposing factors for depressive disorders, such as general vulnerability factors, psychiatric co-morbidity and subthreshold depressive disorders. This linear model explained the relationship just as well as more complicated models.

Conclusions

Alcohol-use disorder severity was a significant linear predictor of first-incident depressive disorders after 3-year follow-up and may be useful in identifying a high-risk group for depressive disorders that could be targeted by prevention strategies.

Keywords: Alcohol use disorders, depressive disorders, DSM-5, NESARC, severity

Introduction

Cross-sectional studies have often revealed a strikingly high prevalence of depressive disorders in persons with DSM-IV alcohol use disorders [AUDs; alcohol abuse (AA) and alcohol dependence (AD)]. Persons with lifetime AD have a two- to four-fold increased risk of lifetime depressive disorders in general population studies (Ross, 1995; Kessler et al. 1997; Hasin et al. 2005, 2007), whereas the prevalence of depressive disorders appears to be even higher in clinical samples of persons with AD (Lynskey, 1998). In contrast, no associations have been found for lifetime AA (Kessler et al. 1997; Hasin et al. 2005). Among alcohol-dependent persons, those with a co-morbid depressive disorder are significantly more disabled and have poorer treatment outcomes (Burns et al. 2005). Therefore, prevention of depressive disorders in alcohol-dependent persons has the potential to enhance mental health care.

However, the nature of the relationship between AUDs and depressive disorders remains poorly understood. Although strong cross-sectional associations were found for AD and depressive disorders (Ross, 1995; Kessler et al. 1997; Lynskey, 1998; Hasin et al. 2005, 2007), retrospective general population and twin studies that attempted to take time order into account did not find significant associations (Hettema et al. 2003; Kuo et al. 2006). In addition, AUDs did not prospectively predict the incidence of major depressive episodes in midlife women (Bromberger et al. 2009). In contrast, other prospective studies showed that AUDs (Rohde et al. 2001) and drug and alcohol dependence (Marmorstein et al. 2010) in late adolescence predicted the presence of major depressive disorder (MDD) in young adulthood. Given these contrasting findings, general population studies examining the first-incidence of depressive disorders are essential for unravelling the time order of comorbidity, a necessary step towards understanding whether there is a causal relationship. To our knowledge, only two large general population prospective studies examined AUDs as predictors of first-incident depressive disorders, one in the United States (Grant et al. 2009) and the other in the Netherlands (de Graaf et al. 2002). These studies failed to find AUDs as significant predictors of future depressive disorders.

One possible explanation for this lack of predictive value is the way AUDs were defined. Both studies characterized AUDs according to DSM-III-R or DSMIV criteria, i.e. AA and AD, as two separate and hierarchical disorders with AD taking precedence over AA if criteria for both are met. While DSM-IV AD diagnoses are reliable and valid, the reliability and validity of AA is lower and more variable (Hasin, 2003; Hasin et al. 2006b). At the same time, many studies show that most AA and AD criteria form a single latent dimension, with AA and AD criteria interspersed across an underlying severity spectrum (Kahler & Strong, 2006; Martin et al. 2006; Saha et al. 2006; Keyes et al. 2010; Shmulewitz et al. 2010). Moreover, the simple count of criteria forms a linear dimension of AUD severity (Hasin & Beseler, 2009; Dawson & Grant, 2010; Dawson et al. 2010), leading to plans to combine AA and AD criteria into one diagnosis in DSM-5 with different severity levels (www.dsm5.org). This research and the resulting diagnostic changes suggest that a dimensional approach to AUDs may provide a more informative phenotype than dichotomized measures based on artificially imposed thresholds.

Since incidence rates of psychiatric disorders are generally low, first-incidence studies require large samples and highly reliable, valid and informative predictors. We will therefore examine whether AUD severity predicts first-incident depressive disorders (major depressive or dysthymic disorder) after 3-year follow-up using prospective data from a large, national sample (Grant et al. 2001, 2007). Note that this is one of the samples that did not find a significant association of AUDs defined in a binary manner and first-incident major depression (Grant et al. 2009). Although AUD severity has been linearly associated with various alcohol measures (Hasin & Beseler, 2009), no other study has ever examined its prospective association with psychiatric co-morbidity, such as depressive disorders. Our aim was, therefore, to examine whether a continuum of AUD severity (as a count of criteria, range 0–10) predicts first-incident depressive disorders in a linear fashion and test whether more complicated models better describe the association. Analyses adjust for well-known depression risk factors such as smoking status, general vulnerability factors [family history (FH) of depressive disorders, FH of AD and childhood trauma], psychiatric co-morbidity (conduct disorder and anxiety disorder) and subthreshold depressive disorders.

Method

Sample

The present study is based on the baseline (Wave 1: 2001–2002) and 3-year follow-up (Wave 2: 2004–2005) data of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The NESARC surveyed a representative sample of the adult (≥18 years) civilian population, residing in household and group quarters, over-sampling black and Hispanic people and young adults aged 18–24 years, with data adjusted for over-sampling and household- and person-level non-response. The weighted data were then adjusted to represent the US civilian population based on data from the 2000 census. A detailed description of the NESARC study design and sampling procedures can be found elsewhere (Grant et al. 2001, 2007). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 43 093 respondents at the baseline measurement, yielding an overall response rate of 81.0%. The followup measurement involved face-to-face re-interviews with all participants in the baseline interview. Excluding respondents ineligible for the follow-up interview because they were deceased (n=1403), deported, mentally or physically impaired (n=781) or on active duty in the armed forces throughout the follow-up period (n=950), the response rate at 3-year follow-up was 86.7%, reflecting 34 653 completed interviews. The cumulative response rate at the follow-up measurement was the product of the baseline and follow-up response rates, or 70.2%. The mean interval between baseline and follow-up interviews was 36.3 (S.E.=2.62) months. All potential NESARC respondents were informed in writing about the nature of the survey, the statistical uses of the survey data, the voluntary aspect of their participation and the federal laws that provide for the confidentiality of identifiable survey information. Respondents who gave consent were then interviewed.

To examine the first-incidence of depressive disorders after 3-year follow-up, we excluded all 696 L. Boschloo et al. participants with a lifetime major depressive (n=4785), dysthymic (n=1166), bipolar 1 (n=1172), bipolar 2 (n=428) and/or hypomanic (n=428) disorder at the baseline measurement. In total, we excluded 7082 of the 34 653 participants with complete data on the baseline and follow-up measurement, leaving a sample of 27 571 participants for the current analyses. To be consistent with previous first-incidence studies on depressive disorders (de Graaf et al. 2002; Grant et al. 2009), no restrictions regarding life-time or current alcohol consumption were applied. Mean age of the present sample is 45.9 (S.E.=0.20) years, 49.5% were female and 69.7% were white, 11.6% African–American and 12.2% Hispanic.

Measures

Diagnostic interview

The diagnostic interview was the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule – DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV; Grant et al. 1995), a structured interview designed for experienced lay interviewers. Computer diagnostic programs implemented DSM-IV criteria for the disorders using AUDADIS-IV data. The depressive and anxiety diagnoses in this report are DSM-IV independent diagnoses, i.e. diagnoses of mental disorders that are not substance-induced and not due to a medical condition. In differentiating primary from substance-induced disorders, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI) and World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) rely on the respondent’s opinion of the cause of individual symptoms. An important AUDADIS improvement in this differentiation is the use of specific questions about the chronological relationship between intoxication or withdrawal and questions about the full depressive syndrome. Specific questions about chronology improve the reliability and validity of MDD diagnoses in substance abusers. The DIS, UM-CIDI and WMH-CIDI also relied on the respondent’s opinion in differentiating primary disorders from those due to a medical condition. The AUDADIS-IV offers a similar improvement: specific questions about chronology of the mental disorder and the medical condition. Diagnoses of MDD presented in this report also ruled out bereavement. Axis I criteria and disorders were assessed identically in the baseline and follow-up versions of the AUDADIS-IV except for the time-frames.

Depressive disorders

In our sample of persons without a lifetime MDD, dysthymic disorder, manic episode or hypomanic episode, we examined the first-incidence of depressive disorders using a diagnosis of a past-year depressive disorder (major depressive or dysthymic disorder) at the 3-year follow-up interview, comparable with previous first-incidence studies on depressive disorders (de Graaf et al. 2002; Grant et al. 2009).

AUD criteria

Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered all DSM-IV criteria for AA and AD, among all participants who were ever drinkers. Clinical as well as general population studies showed that the reliability (Grant et al. 1995; Chatterji et al. 1997; Hasin et al. 1997a, b; Grant et al. 2003) as well as the validity (Cottler et al. 1997; Hasin et al. 1997b; Pull et al. 1997) of AUDADIS-IV alcohol diagnoses ranged from good to excellent. In general, AD diagnoses are reliable and valid. The reliability and validity of AA is often lower and more variable when diagnosed hierarchically, as required in DSM-IV (Hasin, 2003), although AA also has excellent reliability when diagnosed without DSM-IV hierarchical requirements (Hasin et al. 2006b).

Based on empirical evidence (Dawson et al. 2010; Keyes et al. 2010), the DSM-5 workgroup proposed to eliminate the AA criterion involving alcohol-related legal problems but retain the remaining three DSM-IV AA criteria and all seven DSM-IV AD criteria into one diagnosis of an AUD with different levels of severity. Consequently, a DSM-5 diagnosis of an AUD was based on the following AA and AD criteria: failure to fulfil major role obligations (AA); recurrent hazardous use (AA); persistent social or interpersonal problems (AA); tolerance (AD); withdrawal or withdrawal avoidance (AD); drinking more or longer than was intended (AD); persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to quit reduce drinking (AD); great deal of time drinking or recovering from its effects (AD); giving up or reducing occupational, social and/or recreational activities to drink (AD); continued drinking despite physical or psychological problems (AD). The DSM-5 workgroup has also proposed to add a criterion concerning alcohol craving to these 10 existing criteria, but this information was not assessed at the NESARC baseline interview. However, previous studies showed that the other criteria, without alcohol craving, represented the latent variable very well because of the redundancy of craving with the remaining criteria (Keyes et al. 2010). For the present study, AUD severity was based on the simple count of these 10 criteria that were present in the year preceding the baseline interview and was a valid indicator of AUD severity compared with a scale based on item weights according to item response theory measures of severity (Dawson & Grant, 2010; Dawson et al. 2010). Alcohol-use disorder severity predicts first-incidence of depressive disorders 697

Covariates

The following baseline characteristics were used as sociodemographic covariates: age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+ years); gender; race/ethnicity (white, Hispanic, black, Asian, Native American); education (any college versus other); marital status (married versus other). The operationalization of covariates is consistent with other NESARC papers. Analyses were additionally adjusted for baseline smoking status (never smoked, former smoker and current smoker) and three clusters of predisposing factors for depressive disorders: (1) general vulnerability factors (FH of depressive disorders, FH of AD and childhood trauma); (2) psychiatric co-morbidity (conduct disorder and anxiety disorder); (3) subthreshold depressive disorders. From the general vulnerability factors, FH of depressive disorders and FH of AD were considered positive if experienced by parents or siblings as reported by participants. Physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect and sexual abuse before the age of 18 years were assessed to determine the presence (0, 1, 2, 3+ types) of childhood trauma. Baseline psychiatric co-morbidity included lifetime DSM-IV conduct disorder and anxiety disorder (panic disorder with/without agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia and specific phobia) as assessed with the AUDADIS-IV. Analyses were also adjusted for subthreshold depressive disorders as assessed as the number of lifetime MDD symptoms as well as the number of lifetime dysthymia symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Due to the NESARC complex sample design, analyses were conducted using SUDAAN, Version 9.0 (Research Triangle Institute, 2004), a software package that uses Taylor series linearization to adjust variance estimates for complex, multi-stage sample designs. All analyses were adjusted for gender, age, race, education and marital status. Analyses were additionally adjusted for baseline smoking status and predisposing factors for depressive disorders, such as general vulnerability factors, psychiatric co-morbidity and subthreshold depressive disorders.

First, we reported on the first-incidence rates of depressive disorders across AUD severity levels (count of criteria; range 0–10) using descriptive statistics (%, 95% CI of %). Then logistic regression analyses were used to explore the nature of the prospective relationship between AUD severity at baseline and first-incidence of depressive disorders after 3-year follow-up. To determine whether a linear trend explained the relationship between AUD severity and first-incident depressive disorders, we tested a linear model, in which one predictor represented a simple count of none to 10 criteria. We then tested whether this linear model deviated from more complicated models, an analytic method used previously by others (Hasin et al. 2006a; Martin et al. 2006; Beseler & Hasin, 2010). One of these models, the dummy variable model, comprised 10 dummy variables representing all separate levels of AUD severity. Variables were created based on groups defined by the number of AUD criteria met at the baseline interview (none, one, two, etc.), using those with no criteria as the reference group. The partially linear model included a linear trend for none to eight criteria and a category representing the most severe level for nine to 10 criteria. This latter model was created based on visual inspection of the graph representing the dummy variable model (see Results). To test whether these two more complicated models produced significantly different estimates compared with the linear model, we used the Wald statistic. Little or no difference (p>0.05) would support the use of a linear model, as it is most parsimonious in terms of number of parameters.

Results

The overall first-incidence of depressive disorders after 3-year follow-up was 4.34% (S.E.=0.15; results not tabulated) with considerable variation between persons with different AUD severity levels. Table 1 shows that the first-incidence of depressive disorders was low in persons meeting no AUD criteria (4.20%, 95% CI 3.90–4.53%) and much higher in persons meeting nine (25.93%, 95% CI 4.03–74.46%) or 10 (44.47%, 95% CI 7.72–88.45%) criteria.

Table 1.

First-incidence of depressive disorders across alcohol-use disorder severity levels

| Number of criteria at baseline | n | First-incident depressive disorder at 3-year follow-upa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| %a | 95% CIa | ||

| 0 | 24 001 | 4.20 | 3.90–4.53 |

| 1 | 1860 | 3.88 | 2.97–5.07 |

| 2 | 804 | 7.24 | 4.99–10.39 |

| 3 | 398 | 4.06 | 2.23–7.28 |

| 4 | 215 | 6.50 | 3.81–10.88 |

| 5 | 129 | 8.16 | 4.11–15.52 |

| 6 | 74 | 3.66 | 1.04–12.09 |

| 7 | 38 | 9.64 | 3.51–23.84 |

| 8 | 34 | 1.89 | 0.25–13.02 |

| 9 | 12 | 25.93 | 4.03–74.46 |

| 10 | 6 | 44.47 | 7.72–88.45 |

Weighted percentages taking into account the weighted sample.

A linear model of AUD severity, as the simple count of 0–10 criteria, significantly predicted first-incidence of depressive disorders after adjustment for sociodemographics [odds ratio (OR) 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.22, p=0.0006; see Table 2]. Even after taking into account the effects of smoking status and depression risk factors, such as general vulnerability factors, psychiatric co-morbidity and subthreshold depressive disorders at the baseline interview, the linear model of AUD severity was a significant predictor of first-incident depressive disorders (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.19, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Alcohol-use disorder severity predicting first-incidence of depressive disorders

| Predictor at baseline | First-incident depressive disorder at 3-year follow-up

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | p | ORb | 95% CI | p | |

| Alcohol-use disorder severity | 1.14 | 1.06–1.22 | 0.0006 | 1.10 | 1.01–1.19 | 0.02 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Female gender | 2.22 | 1.92–2.63 | <0.0001 | 2.04 | 1.72–2.44 | <0.0001 |

| Age: | ||||||

| 18–29 years | 1.52 | 1.24–1.86 | 0.0001 | 1.68 | 1.36–2.07 | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 years | 1.40 | 1.16–1.70 | 0.0008 | 1.40 | 1.14–1.72 | 0.002 |

| 40–49 years | 1.53 | 1.26–1.85 | <0.0001 | 1.43 | 1.17–1.75 | 0.0006 |

| 50+ years | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Race/ethnicity: | ||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.16 | 0.95–1.40 | 0.14 | 1.19 | 0.98–1.43 | 0.07 |

| Black | 0.79 | 0.64–0.98 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.64–1.00 | 0.05 |

| Asian | 0.76 | 0.53–1.09 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 0.61–1.25 | 0.45 |

| Native American | 1.53 | 0.92–2.53 | 0.10 | 1.39 | 0.83–2.32 | 0.21 |

| Education: some college or beyond | 0.80 | 0.69–0.93 | 0.004 | 0.83 | 0.71–0.96 | 0.02 |

| Marital status: married | 0.82 | 0.71–0.94 | 0.005 | 0.82 | 0.71–0.94 | 0.005 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Never | – | – | – | Reference | ||

| Former smoker | – | – | – | 1.16 | 0.93–1.45 | 0.22 |

| Current smoker | – | – | – | 1.15 | 0.97–1.36 | 0.15 |

| General vulnerability factors | ||||||

| FH of depressive disorders (yes) | – | – | – | 1.17 | 0.98–1.40 | 0.09 |

| FH of alcohol dependence (yes) | – | – | – | 1.04 | 0.88–1.23 | 0.64 |

| Childhood trauma: | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | Reference | ||

| 1 type | – | – | – | 1.65 | 1.38–1.96 | <0.0001 |

| 2 types | – | – | – | 1.90 | 1.49–2.43 | <0.0001 |

| 3+ types | – | – | – | 3.01 | 2.37–3.81 | <0.0001 |

| Psychiatric co-morbidity | ||||||

| Conduct disorder (yes) | – | – | – | 0.55 | 0.32–0.94 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety disorder (yes) | – | – | – | 1.48 | 1.21–1.82 | 0.0003 |

| Subthreshold disorders | ||||||

| Number of lifetime MDD symptoms | – | – | – | 1.11 | 1.09–1.14 | <0.0001 |

| Number of lifetime dysthymia symptoms | – | – | – | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | 0.33 |

OR, odds ratio; FH, family history; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Adjusted for sociodemographics.

Adjusted for sociodemographics, smoking status, general vulnerability factors, psychiatric co-morbidity and subthreshold depressive disorders.

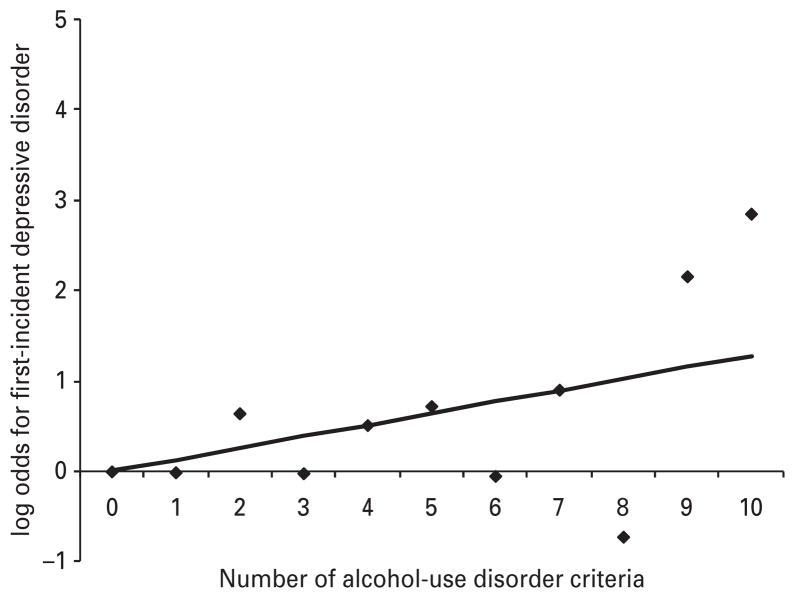

To explore whether this linear model deviated from the two more complicated models in predicting the log odds of first-incident depressive disorders, a graph (Fig. 1) was plotted to visualize the coefficient from the linear model (slope coefficient of 0.13, S.E.=0.04) relative to the 10 coefficients from a dummy variable model representing all separate levels of severity. No significant difference in explained variance was found between the two models (χ2=13.36, p=0.15). Since Fig. 1 suggested that another partially linear model with a linear trend for none to eight criteria and a separate category for nine to 10 criteria might better describe the association, we also tested whether this partially linear model better explained the relationship than the linear model, but this was not the case. These results confirmed that a linear model best and most simply explained the relationship between the count of AUD criteria and first-incident depressive disorders. As Fig. 1 might suggest that the significant slope of the linear model could be explained by the high log ORs for persons meeting nine to 10 criteria, we also tested the linear model, adjusted for socio-demographics, in a subsample of persons meeting none to eight criteria. In this sensitivity analysis, the linear model was still a significant predictor of first-incidence of depressive disorders (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.03–1.18, p=0.004), showing that our findings were not exclusively due to the high first-incidence rates in persons meeting nine or 10 criteria.

Fig. 1.

Alcohol-use disorder severity predicting firstincidence of depressive disorders. Linear model shown by a line, dummy variable model shown in symbols (◆). Adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, education and marital status.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the role of AUD severity as a risk factor of first-incident depressive disorders. The first-incidence of depressive disorders after 3 years of follow-up varied from 4.2% in persons meeting no AUD criteria to 25.9% and 44.5% in persons meeting nine or all 10 criteria, respectively. The count of AUD criteria predicted the first-incidence of depressive disorders in a linear fashion with an OR of 1.14. This means that the risk of first-incident depressive disorders is slightly higher in persons meeting only one criterion but gradually increases with the number of AUD criteria met. Taken together, AUD severity appeared to be useful in identifying persons with an increased risk of developing depressive disorders who could be targeted by prevention strategies.

Our study demonstrated that AUD severity prospectively predicted first-incidence of depressive disorders. AUDs have been hypothesized to cause the onset of major depression (Hasin & Grant, 2002; Wang & Patten, 2002; Fergusson et al. 2009) due to their interpersonal and social consequences (Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000). This may indirectly be supported by our finding that the risk of first-incident depressive disorders increases with AUD severity and is highest in persons meeting nine or 10 criteria. AUD criteria involving interpersonal and social consequences [i.e. social or interpersonal problems (AA), giving up or reducing activities (AD) and failure to fulfil roles (AA)] have shown to be the most severe and are more likely to be present in persons meeting many other criteria (Dawson et al. 2010). Although some note that heavy alcohol consumption pharmacologically induces depressive symptoms (Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000), AUDADIS-IV questions on symptoms of major depression were designed to screen out substance-induced depressive disorders, so this is not a likely explanation of our finding.

Shared genetic and environmental risk factors may independently cause the onset of alcohol problems and depressive disorders (e.g. Kendler et al. 1993; Prescott et al. 2000) and, therefore, explain their comorbidity. However, we found that the association between AUD severity and first-incident depressive disorder could not be explained by shared risk factors such as sociodemographics, smoking status, FH of depressive disorders, FH of AD, childhood trauma, psychiatric co-morbidity and subthreshold depressive disorders because inclusion of these factors in the models did not substantially change the results. These findings may be additional support for a causal model in which alcohol problems result in the development of depressive disorders.

Contrasting findings have been reported by previous studies on the prospective relationship between AUDs and depressive disorders (Rohde et al. 2001; de Graaf et al. 2002; Hettema et al. 2003; Kuo et al. 2006; Grant et al. 2009; Marmorstein et al. 2010). One possible explanation for this may be the heterogeneity (e.g. severity) of AUD diagnoses in the various studies. This is supported by our study, showing a significant association between AUD severity and first-incident depressive disorders, whereas a previous study on binary categorical AUDs in the same population did not (Grant et al. 2009). In general, mild disorders are far more prevalent in general population studies than severe disorders (Cohen & Cohen, 1984) and, as the risk of first-incident depressive disorders gradually increased with AUD severity, these mild disorders are less likely to predict first-incident depressive disorders. On the other hand, persons with severe disorders are likely to be over-represented in clinical studies and may explain the stronger cross-sectional relationship between AUDs and depressive disorders as reported in clinical versus community samples. A substantial proportion of persons with a severe AUD receive some form of treatment; for example, in our sample 50.7% of persons meeting nine or 10 criteria had received some kind of addiction treatment in the year before the baseline interview. While the prevalence of severe AUDs is low when considered in the context of the entire general population, individuals with such severity are likely to be under supervision of a health care professional and, therefore, may be reached more easily with prevention strategies for depressive disorders. Assessment of AUD severity by the simple count of positive criteria may be a very simple strategy for identification of persons at a high risk for developing these disorders. This screening method has the potential to be highly effective as one-third of those persons with a severe AUD are likely to develop a depressive disorder.

The heterogeneity of AUDs highlights the importance of using a more informative phenotype as severity rather than categorical diagnoses based on artificially imposed thresholds. As the count of AUD criteria form a single dimension of severity (see also Hasin & Beseler, 2009; Dawson & Grant, 2010; Dawson et al. 2010), DSM-5 will offer a dimensional approach, the details of which are still under development. Our findings support the plan in DSM-5 to distinguish different levels of severity within diagnoses.

This study has strengths and limitations. Strengths of our study include that we were the first to prospectively examine whether AUD severity predicted first-incidence of depressive disorders after 3-year follow-up. We used data of a very large representative general population study and a highly informative phenotype of AUD severity. Our finding that AUD severity linearly predicted first-incident depressive disorders was robust as a linear model for none to eight criteria also had a significant slope. Thus, our findings were not only due to the high log ORs for nine and 10 criteria. A limitation is that all diagnostic questions are subject to recall, self-report and social desirability bias. Second, no information about alcohol craving was assessed at the NESARC baseline interview. As the DSM-5 workgroup has proposed to add ‘alcohol craving’ to the 10 existing criteria, this would have been valuable information. However, previous studies have reported that the 10 criteria, without craving, represented the latent variable of AUD severity very well, because of the high cohesion (in fact, redundancy) of craving with the other criteria (Keyes et al. 2010). Another important limitation may be the limited power to test whether the linear model deviated from more complicated models (e.g. the dummy variable model) as especially the number of respondents at the severe end of the AUD severity spectrum was small. Therefore, studies among persons with more severe AUDs, for example, in high-risk or clinical samples, are needed. Future studies might provide important additional information by not only operationalizing AUD severity as a count of criteria, but also as defined in alternative ways, such as level of social, occupational or physical impairment, quantity of alcohol consumption or age of onset of drinking.

In conclusion, we found that AUD severity predicted first-incidence of depressive disorders in a linear fashion, even after taking into account important depression risk factors as potential confounders. This means that the risk of first-incident depressive disorders gradually increases and that AUD severity may be a useful indicator of a high-risk group for depressive disorders and an important target for the prevention of depression.

Acknowledgments

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions is funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) with supplemental support from National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Support for preparation of this manuscript came from grant 31160004 (Boschloo, van den Brink, Penninx) and 60–60600–97–250 (Boschloo) from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Zon-Mw), K05AA014223 (Hasin) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Hasin, Wall).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Beseler CL, Hasin DS. Cannabis dimensionality: dependence, abuse and consumption. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Matthews K, Youk A, Brown C, Feng W. Predictors of first lifetime episodes of major depression in midlife women. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:55–64. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L, Teesson M, O’Neill K. The impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on alcohol treatment outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100:787–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.001069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:171–185. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’s illusion. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–1182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, Mavreas V, Pull C, Hasin DS, Compton WM, Rubio-Stipec M, Mager D. Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF. Should symptom frequency be factored into scalar measures of alcohol use disorder severity ? Addiction. 2010;105:1568–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Saha TD, Grant BF. A multidimensional assessment of the validity and utility of alcohol use disorder severity as determined by item response theory models. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;107:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Ravelli A, Smit F, Vollebergh WAM. Predictors of first incidence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the general population: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106:303–313. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Saha TD, Smith SM, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan KK, Stinson FS. Source and Accuracy Statement: The Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: The Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Classification of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Research & Health. 2003;27:5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Beseler CL. Dimensionality of lifetime alcohol abuse, dependence and binge drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997a;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. Major depression in 6050 former drinkers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:794–800. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Liu X, Alderson D, Grant BF. DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a categorical or dimensional phenotype? Psychological Medicine. 2006a;36:1695–1705. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Samet S, Nunes E, Meydan J, Matseoane K, Waxman R. Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance users assessed with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006b;163:689–696. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States – results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: validity in community sample heavy drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997b;21:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. The effects of anxiety, substance use and conduct disorder on risk of major depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1423–1432. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR. A Rasch model analysis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence items in the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. Alcoholism and major depression in women: a twin study of the causes of comorbidity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:690–698. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;41:629–640. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo PH, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. The temporal relationship of the onsets of alcohol dependence and major depression: using a genetically informative study design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1153–1162. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT. The comorbidity of alcohol dependence and affective disorders: treatment implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;52:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG, Malone SM. Longitudinal associations between depression and substance dependence from adolescence through early adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;107:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenburcher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Sex-specific genetic influences on the comorbidity of alcoholism and major depression in a population-based sample of US twins. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:803–811. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, Cottler LB, Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blaine J, Mager D, Ustun BT. Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN), Version 9.0. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Kahkler CW, Seeley JR, Brown RA. Natural course of alcohol use disorders from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE. DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence and psychiatric comorbidity in Ontario: results from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:111–128. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01150-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Beseler C, Aharonovic E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychological Review. 2000;20:173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Patten SB. Prospective study of frequent heavy alcohol use and the risk of major depression in the Canadian general population. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;15:42–45. doi: 10.1002/da.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]