Abstract

Since DSM-IV was published in 1994, its approach to substance use disorders has come under scrutiny. Strengths were identified (notably, reliability and validity of dependence), but concerns have also arisen. The DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work Group considered these issues and recommended revisions for DSM-5. General concerns included whether to retain the division into two main disorders (dependence and abuse), whether substance use disorder criteria should be added or removed, and whether an appropriate substance use disorder severity indicator could be identified. Specific issues included possible addition of withdrawal syndromes for several substances, alignment of nicotine criteria with those for other substances, addition of biomarkers, and inclusion of nonsubstance, behavioral addictions.

This article presents the major issues and evidence considered by the work group, which included literature reviews and extensive new data analyses. The work group recommendations for DSM-5 revisions included combining abuse and dependence criteria into a single substance use disorder based on consistent findings from over 200,000 study participants, dropping legal problems and adding craving as criteria, adding cannabis and caffeine withdrawal syndromes, aligning tobacco use disorder criteria with other substance use disorders, and moving gambling disorders to the chapter formerly reserved for substance-related disorders. The proposed changes overcome many problems, while further studies will be needed to address issues for which less data were available.

DSM is the standard classification of mental disorders used for clinical, research, policy, and reimbursement purposes in the United States and elsewhere. It therefore has widespread importance and influence on how disorders are diagnosed, treated, and investigated. Since its first publication in 1952, DSM has been reviewed and revised four times; the criteria in the last version, DSM-IV-TR, were first published in 1994. Since then, knowledge about psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders, has advanced greatly. To take the advances into account, a new version, DSM-5, was published in 2013. In 2007, APA convened a multidisciplinary team of experts, the DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work Group (Table 1), to identify strengths and problems in the DSM-IV approach to substance use disorders and to recommend improvements for DSM-5.

TABLE 1.

DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work Groupa

| Name | Degree(s) | Specialization | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles O’Brien (chair)b | M.D., Ph.D. | Addiction psychiatry | USA |

| Marc Auriacombe | M.D. | Addiction psychiatry | France |

| Guilherme Borges | Sc.D. | Epidemiology | Mexico |

| Kathleen Bucholz | Ph.D. | Epidemiology | USA |

| Alan Budney | Ph.D. | Substance use disorder treatment, marijuana | USA |

| Wilson Comptonb | M.D., M.P.E | Epidemiology, addiction psychiatry | USA |

| Thomas Crowleyc | M.D. | Psychiatry | USA |

| Bridget F. Grantb | Ph.D., Ph.D. | Epidemiology, biostatistics, survey research | USA |

| Deborah S. Hasin | Ph.D. | Epidemiology of substance use and psychiatric disorders | USA |

| Walter Ling | M.D. | Addiction psychiatry | USA |

| Nancy M. Petry | Ph.D. | Substance use and gambling treatment | USA |

| Marc Schuckit | M.D. | Genetics and comorbidity | USA |

In addition to the scientists listed here who were members during the entire duration of the process, a list of consultants and advisers who served on various subcommittees and contributed substantially to the discussion is contained in the official publication of DSM-5.

Also a DSM-5 Task Force member.

Co-chair, 2007–2011.

Using a set of 2006 reviews (1) as a starting point, the work group noted weaknesses, highlighted gaps in knowledge, identified data sets to investigate possible solutions, encouraged or conducted analyses to fill knowledge gaps, monitored relevant new publications, and formulated interim recommendations for proposed changes. The work group elicited input on proposed changes through commentary (2), expert advisers, the DSM-5 web site (receiving 520 comments on substance use disorders), and presentations at over 30 professional meetings (see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). This input led to many further analyses and adjustments.

The revisions proposed for DSM-5 aimed to overcome the problems identified with DSM-IV, thereby providing an improved approach to substance use disorders. To this end, the largest question was whether to keep abuse and dependence as two separate disorders. This issue, which applies across substances (alcohol, cannabis, etc.), had the most data available. Other cross-substance issues included the addition or removal of criteria, the diagnostic threshold, severity indicator(s), course specifiers, substance-induced disorders, and biomarkers. Substance-specific issues included new withdrawal syndromes, the criteria for nicotine disorders, and neurobehavioral disorder associated with pre-natal alcohol exposure. Additional topics for consideration involved gambling and other putative non-substance-related behavioral addictions. This article presents the evidence that the work group considered on these issues and the resulting recommendations.

Overarching Issues

Should Abuse and Dependence Be Kept as Two Separate Diagnoses?

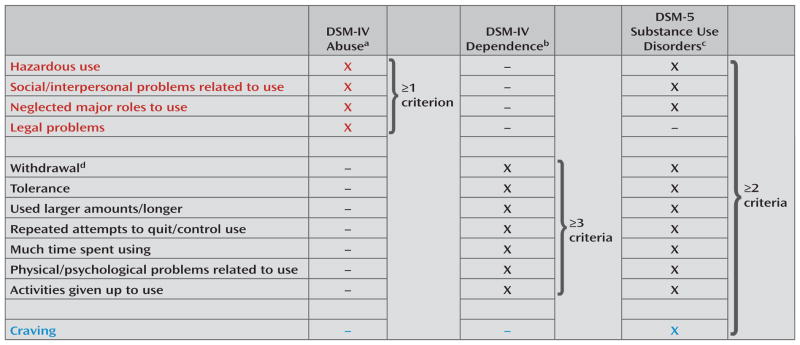

The DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse and dependence are shown in Figure 1. Dependence was diagnosed when three or more dependence criteria were met. Among those with no dependence diagnosis, abuse was diagnosed when at least one abuse criterion was met. The division into two disorders was guided by the concept that the “dependence syndrome” formed one dimension of substance problems, while social and interpersonal consequences of heavy use formed another (3, 4). Although the dimensions were assumed to be related (3, 4), DSM-IV placed dependence above abuse in a hierarchy by stipulating that abuse should not be diagnosed when dependence was present. The dependence diagnosis represented a strength of the DSM-IV approach to substance use disorders: it was consistently shown to be highly reliable (5) and was validated with antecedent and concurrent indicators such as treatment utilization, impaired functioning, consumption, and comorbidity (6–9).

FIGURE 1. DSM-IV and DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorders.

a One or more abuse criteria within a 12-month period and no dependence diagnosis; applicable to all substances except nicotine, for which DSM-IV abuse criteria were not given.

b Three or more dependence criteria within a 12-month period.

c Two or more substance use disorder criteria within a 12-month period.

d Withdrawal not included for cannabis, inhalant, and hallucinogen disorders in DSM-IV. Cannabis withdrawal added in DSM-5.

However, other aspects of the DSM-IV approach were problematic. Some issues pertained to the abuse diagnosis and others pertained to the DSM-IV-stipulated relationship of abuse to dependence. First, when diagnosed hierarchically according to DSM-IV, the reliability and validity of abuse were much lower than those for dependence (5, 10). Second, by definition, a syndrome requires more than one symptom, but nearly half of all abuse cases were diagnosed with only one criterion, most often hazardous use (11, 12). Third, although abuse is often assumed to be milder than dependence, some abuse criteria indicate clinically severe problems (e.g., substance-related failure to fulfill major responsibilities). Fourth, common assumptions about the relationship of abuse and dependence were shown to be incorrect in several studies (e.g., that abuse is simply a prodromal condition to dependence [13–17] and that all cases of dependence also met criteria for abuse, a concern particularly relevant to women and minorities [18–20]).

The problems pertaining to the DSM-IV hierarchy of dependence over abuse also included “diagnostic orphans” (21–24), the case of two dependence criteria and no abuse criteria, potentially a more serious condition than abuse but ineligible for a diagnosis. Also, when the abuse criteria were analyzed without regard to dependence, their test-retest reliability improved considerably (5), suggesting that the hierarchy, not the criteria, led to their poor reliability. Finally, factor analyses of dependence and abuse criteria (ignoring the DSM-IV hierarchy) showed that the criteria formed one factor (25, 26) or two highly correlated factors (27–34), suggesting that the criteria should be combined to represent a single disorder.

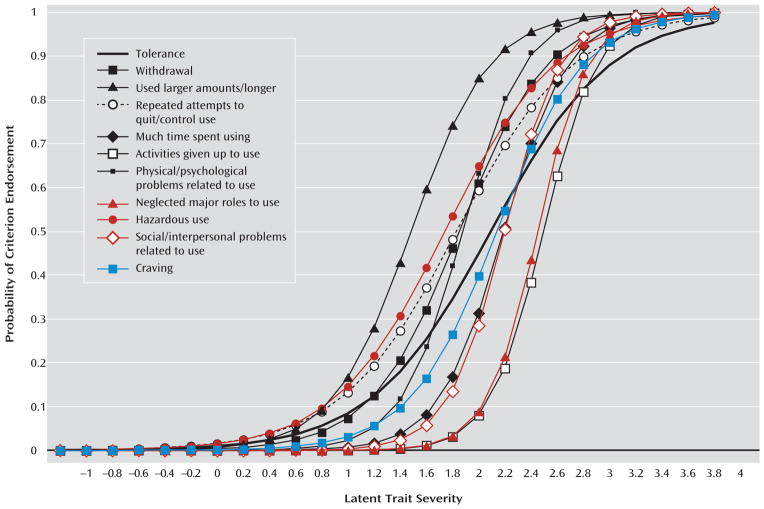

To further investigate the relationship of abuse and dependence criteria, the work group and other researchers used item response theory analysis, which builds on factor analysis, to better understand how items (in this case, the criteria) relate to each other. Item response theory models indicate criterion severity (inversely related to frequency: rarely endorsed criteria are considered more severe) and discrimination (how well the criterion differentiates between respondents with high and low severity of the condition). The results from these analyses are often presented graphically (Figure 2), where each curve represents a criterion. Curves toward the right indicate criteria of greater severity; steeper slopes indicate better discrimination (see Table S2 in the online data supplement for more detail about Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Information Characteristic Curves from Item Response Theory Analysis of DSM-IV Alcohol Abuse and Dependence Criteria, Required to Persist Across 3 Years of Follow-Upa,b.

a Red curves: DSM-IV abuse criteria. Black curves: DSM-IV dependence criteria. Blue curve: Craving.

b Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Wave 2 (2004–2005), conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Participants were noninstitutionalized civilians age 20 years and older (N=34,653). The NESARC had a multistage design and oversampled blacks, Hispanics, and young adults. Analyses were conducted with Mplus (version 6.12, Los Angeles, Muthén & Muthén, 2011) and incorporated sample weights to adjust standard errors appropriately. See supplementary Table S2 for more detail on this analysis.

Table 2 lists the 39 articles on the item response theory studies that were examined or conducted by the work group, which include over 200,000 study participants. Two main findings arose, with similar results across substances, countries, adults, adolescents, patients and nonpatients. First, unidimensionality was found for all DSM-IV criteria for abuse and dependence except legal problems, indicating that dependence and the remaining abuse criteria all indicate the same underlying condition. Second, while severity rankings of criteria varied somewhat across studies, abuse (red curves in Figure 2) and dependence (black curves in Figure 2) criteria were always intermixed across the severity spectrum, similar to the curves shown in Figure 2. Collectively, this large body of evidence supported removing the distinction between abuse and dependence.

TABLE 2.

Item Response Theory Studies on DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Criteria

| Authors, Year (Source) | Substance | Country | Survey/Samplea | Sample Size | Diagnosis Instrumentb | Year of Data Collection | Time Frame | Unidimensionality Shown? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult, general population | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Saha et al., 2006 (35) | Alcohol | USA | NESARC | 20,846 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Current | Yes |

| Saha et al., 2007 (36) | Alcohol | USA | NESARC | 20,846 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Current | Yes |

| Gillespie et al., 2007 (31) | Cannabis | USA | Adult twins | 1,491 | SCID | 1990s | Lifetime | Yes |

| Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007 (37) | Amphetamine | USA | NESARC | 2,025 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Cannabis | USA | NESARC | 8,933 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Cocaine | USA | NESARC | 2,672 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Hallucinogens | USA | NESARC | 2,525 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Inhalants | USA | NESARC | 728 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Opioids | USA | NESARC | 2,060 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Sedatives | USA | NESARC | 1,896 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Tranquilizers | USA | NESARC | 1,487 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Compton et al., 2009 (38) | Cannabis | USA | NESARC | 1,603 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Current | Yes |

| McBride et al., 2010 (39) | Nicotine | USA | NESARC | 6,185 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 2004–2005 |

Current and lifetime | Yes (dependence only) |

| Saha et al., 2010 (40) | Nicotine | USA | NESARC | 7,852 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 2004–2005 |

Current | Yes (dependence only) |

| Shmulewitz et al., 2010 (41) | Alcohol | Israel | Household | 1,160 | AUDADIS-IV | 2007–2009 | Current and lifetime | Yes |

| Keyes et al., 2011 (42) | Alcohol | USA | NLAES | 18,352 | AUDADIS-IV | 1991–1992 | Current | Yes |

| Kerridge et al., 2011 (43) | Hallucinogens | USA | NESARC | 2,176 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Inhalants | USA | NESARC | 664 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Saha et al., 2012 (44) | Amphetamine | USA | NESARC | 1,750 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Cocaine | USA | NESARC | 2,528 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Opioids | USA | NESARC | 1,815 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Sedatives | USA | NESARC | 1,609 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Tranquilizers | USA | NESARC | 1,301 | AUDADIS-IV | 2001–2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Shmulewitz et al., 2011 (45) | Nicotine | Israel | Household | 727 | AUDADIS-IV | 2007–2009 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Wu et al., 2011 (46) | Opioids | USA | NSDUH | 2,824 | Survey-specific instrument | 2007 | Current | Yes |

| Mewton et al., 2011 (47) | Alcohol | Australia | NSMHWB | 7,746 | CIDI version 2.0 (modified) | 1997 | Current | Yes |

| Gilder et al., 2011 (48) | Alcohol | USA | American Indians | 530 | SSAGA | 1990s | Lifetime | Yes |

| Casey et al., 2012 (49) | Alcohol | USA | NESARC | 22,177 | AUDADIS-IV | 2004–2005 | Current | Yes |

| Wu et al., 2012 (50) | Cannabis | USA | NSDUH | 6,917 | Survey-specific instrument | 2008 | Current | Yes |

|

| ||||||||

| Adult, clinical or mixed | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Langenbucher et al., 2004 (51) | Alcohol | USA | Clinical | 372 | CIDI–SAM | 1990s | Lifetime | Yes |

| Cannabis | USA | Clinical | 262 | CIDI–SAM | 1990s | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Cocaine | USA | Clinical | 225 | CIDI–SAM | 1990s | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Wu et al., 2009 (52) | Cocaine | USA | Clinical | 366 | DSM-IV checklist | 2001–2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) |

| Opioids | USA | Clinical | 354 | DSM-IV checklist | 2001–2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) | |

| Wu et al., 2009 (53) | Alcohol | USA | Clinical | 462 | DSM-IV checklist | 2001–2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) |

| Cannabis | USA | Clinical | 311 | DSM-IV checklist | 2001–2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) | |

| Borges et al., 2010 (54) | Alcohol | Multinational | ED | 3,191 | Adapted CIDI | 1995–2003 | Current | Yes |

| Alcohol | Argentina | ED | 662 | Adapted CIDI | 2001 | Current | Yes | |

| Alcohol | Mexico | ED | 547 | Adapted CIDI | 1996–1997 | Current | Yes | |

| Alcohol | Poland | ED | 1,098 | Adapted CIDI | 2002–2003 | Current | Yes | |

| Alcohol | USA | ED | 884 | Adapted CIDI | 1995–1996 | Current | Yes | |

| Borges et al., 2011 (55) | Alcohol | Argentina, Mexico, Poland, USA | ED | 3,191 | CIDI | 1995–2003 | Current | Yes |

| McCutcheon et al., 2011 (56) | Alcohol | USA | COGA | 8,605 | SSAGA | 1989–1996 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Hasin et al., 2012 (57) | Alcohol | USA | Clinical | 543 | PRISM | 1994–1999 | Current | Yes |

| Cannabis | USA | Clinical | 340 | PRISM | 1994–1999 | Current | Yes | |

| Cocaine | USA | Clinical | 483 | PRISM | 1994–1999 | Current | Yes | |

| Opioids | USA | Clinical | 364 | PRISM | 1994–1999 | Current | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||

| Adolescent, general population | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Harford et al., 2009 (58) | Alcohol | USA | NSDUH | 133,231 | Survey-specific instrument | 2002–2005 | Current | Yes |

| Strong et al., 2009 (59) | Nicotine | USA | 6th–10th graders | 296 | DSM-IV nicotine dependence measure; mFTQ; NDSS | 2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) |

| Wu et al., 2009 (60) | Opioids | USA | NSDUH | 1,290 | Survey-specific instrument | 2006 | Current | Yes |

| Beseler et al., 2010 (61) | Alcohol | USA | College students | 353 | 11-item self- report measure (based on DSM criteria) | 2007 | Current | Yes |

| Rose and Dierker, 2010 (62) | Nicotine | USA | NSDUH | 2,758 | Survey-specific instrument | 1995–1998 | Current | Yes (dependence only) |

| Wu et al., 2010 (63) | Hallucinogens | USA | NSDUH | 1,548 | Survey-specific instrument | 2004–2006 | Current | Yes |

| Hagman and Cohn, 2011 (64) | Alcohol | USA | College students | 396 | Survey-specific instrument | 2010 | Current | Yes |

| Mewton et al., 2011 (65) | Alcohol | Australia | NSMHWB | 853 | CIDI version 2.0 (modified) | 1997 | Current | Yes (“little evidence for DSM-IV abuse/dependence distinction in young adulthood”) |

| Piontek et al., 2011 (66) | Cannabis | France | SHCDDP | 3,641 | M-CIDI | 2008 | Current | Yes |

| Strong et al., 2012 (67) | Nicotine | USA | 6th–10th graders and relatives | 556 | DSM-IV nicotine dependence measure; mFTQ; NDSS | 2003 | Current | Yes (dependence only) |

|

| ||||||||

| Adolescent, clinical or mixed | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Martin et al., 2006 (28) | Alcohol | USA | Clinical | 464 | SCID | 2002 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Cannabis | USA | Clinical | 417 | SCID | 2002 | Lifetime | Yes | |

| Gelhorn et al., 2008 (68) | Alcohol | USA | Mixed | 5,587 | CIDI-SAM | 1993–2007 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Hartman et al., 2008 (69) | Cannabis | USA | Mixed | 5,587 | CIDI-SAM | 1993–2007 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Perron et al., 2010 (70) | Inhalants | USA | Clinical | 279 | DIS-IV | 2004 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Chung et al., 2012 (71) | Nicotine | USA | Clinical | 471 | SCID | 1990–2009 | Lifetime | Yes |

NESARC=National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions; NLAES=National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey; NSDUH=National Survey on Drug Use and Health; NSMHWB=National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being (Australia); ED=emergency department; COGA=Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism; SHCDDP=Survey on Health and Consumption during the Day of Defense Preparation.

AUDADIS-IV=Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV; CIDI=Composite International Diagnostic Interview; SAM=substance abuse module; SSAGA=Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism; PRISM=Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders; mFTQ=Modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire; NDSS=Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale; DIS=NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule.

Substance use prevalence, attitudes, and norms vary across groups, settings, and cultures (72–74). Therefore, the work group examined the studies listed in Table 2 in detail for evidence of age, gender, or other cultural bias in the DSM-5 substance use disorder criteria. Such differences are identified in an item response theory framework by testing for differential item functioning (i.e., whether the likelihood of endorsing a criterion differs by group after accounting for mean group differences in the underlying substance use disorders trait). With the exception of legal problems, the criteria did not consistently indicate differential item functioning across studies. Even where differential item functioning was found (e.g., see references 35 and 36), no evidence of differential functioning of the total score (i.e., the underlying substance use disorders trait) was found. Thus, consistent gender or cultural bias was not found, although the extent of the changes proposed for DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders suggested that there would be value in additional research using different analytic strategies to examine whether gender, age, or ethnic bias exists in the criteria.

DECISION: For DSM-5, combine abuse and dependence criteria into one disorder (Figure 1), with two additional changes indicated below.

Should Any Diagnostic Criteria Be Dropped?

If any criteria can be removed while retaining diagnostic accuracy, the set will be easier to use in clinical practice. The work group considered whether two criteria could be dropped: legal problems and tolerance.

Legal problems

Reasons to remove legal problems from the criteria set included very low prevalence in adult samples (31, 35, 37, 38, 41, 57) and in many (58, 61, 69) although not all (58, 60, 68) adolescent samples, low discrimination (28, 36, 57, 64, 66, 69, 75), poor fit with other substance use disorder criteria (28, 32, 35, 47, 51, 76), and little added information in item response theory analyses (28, 37, 41, 44). Some clinicians were concerned that dropping legal problems would leave certain patients undiagnosed, an issue specifically addressed among heavy alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and heroin users in methadone and dual-diagnosis psychiatric settings (57). None of these patients reported substance-related legal problems as their only criterion or “lost” a DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnosis without this criterion. Thus, legal problems are not a useful substance use disorder criterion, although such problems may be an important treatment focus in some settings.

Tolerance

Concerns about the tolerance criterion included its operationalization, occasional poor fit with other criteria (51), occasional differential item functioning (68), and relevance to the underlying disorder (77). However, most item response theory articles on substance use disorder criteria (Table 2) did not find anything unique about tolerance relative to the other criteria.

DECISION: Drop legal problems as a DSM-5 diagnostic criterion.

Should Any Criteria Be Added?

If new criteria increase diagnostic accuracy, the set will be improved by their addition. The work group considered two criteria for possible addition: craving and consumption.

Craving

Support for craving as a substance use disorder criterion comes indirectly from behavioral (78–82), imaging, pharmacology (83), and genetics studies (84). Some believe that craving and its reduction is central to diagnosis and treatment (83, 85), although not all agree (86, 87). Craving is included in the dependence criteria in ICD-10, so adding craving to DSM-5 would increase consistency between the nosologies.

Item response theory analyses of data from general population and clinical samples in the United States and elsewhere (42, 45, 47, 49, 57, 88) were used to determine the relationship of craving to the other substance use disorder criteria and whether its addition improved the diagnosis. Craving was measured using questions about a strong desire or urge to use the substance, or such a strong desire to use that one couldn’t think of anything else. Across studies, craving fit well with the other criteria and did not perturb their factor loadings, severity, or discrimination. Differential item functioning was generally no more pronounced for craving than for other criteria. In general population samples (e.g., the blue curve in Figure 2), craving fell within the midrange of severity (42). In clinical samples, craving was in the mid-to-lower range of severity, likely because of high prevalence (57). Some studies suggested that craving was redundant with other criteria (47, 49). Using visual inspection to compare item response theory total information curves for the DSM-5 substance use disorder criteria with and without craving produced inconsistent results (42, 47, 88). Using statistical tests to compare total information curves, the addition of craving to the dependence criteria did not significantly add information (45, 57). However, when craving and the three abuse criteria were added, total information was increased significantly for nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and heroin, although not for cocaine use disorders (45, 57). Clinicians expressed enthusiasm about adding craving at work group presentations and on the DSM-5 web site. In the end, while the psychometric benefit in adding a craving criterion was equivocal, the view that craving may become a biological treatment target (a nonpsychometric perspective) prevailed. While awaiting the development of biological craving indicators, clinicians and researchers can assess craving with questions like those used in the item response theory studies (42, 45, 47, 49, 57, 88).

Consumption

The work group considered adding quantity or frequency of consumption as a criterion. A putative criterion of five or more drinks per occasion for men and four or more drinks for women fit well with other criteria in the U.S. general population (36), as did at least weekly cannabis use and daily cigarette use (38, 40). However, issues included worsening of model fit (41), unclear utility among cannabis users (66), and lack of a uniform cross-national alcohol indicator (54). Quantifying other illicit drug consumption patterns is even more difficult.

DECISION: Do not add consumption. Add “craving or a strong desire or urge to use the substance” to the DSM-5 substance use disorder criteria (Figure 1). Encourage further research on the role of craving among substance use disorder criteria.

What Should the Diagnostic Threshold Be?

The studies in Table 2 and others (89–91) demonstrate that the substance use disorders criteria represent a dimensional condition with no natural threshold. However, a binary (yes/no) diagnostic decision is often needed. To avoid a marked perturbation in prevalence without justification, the work group sought a threshold for DSM-5 substance use disorders that would yield the best agreement with the prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders combined. To determine this threshold, data from general population and clinical samples were used to compute prevalences and agreement (kappa) between DSM-5 substance use disorders and DSM-IV dependence or abuse, examining thresholds of two or more to four or more DSM-5 criteria (Table 3). As shown, prevalence was very similar, and agreement (ranging from very good to excellent) appeared maximized with the threshold of two or more criteria, so it was selected. Another recent large independently conducted study further supported this threshold (92).

TABLE 3.

Agreement Between DSM-IV Abuse/Dependence and DSM-5 Substance Use Disorders at Different Diagnostic Thresholds

| Sample (source) | Sample Size | Prevalence | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (6) | |||

| Drinkers, last 12 monthsa | 20,836 | ||

| DSM-IV alcohol | 0.10 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 0.11 | 0.73 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 0.06 | 0.73 | |

| Collaborative studies on genetics of alcoholism nonproband adults (56) | |||

| Drinkers, lifetime | 6,673 | ||

| DSM-IV alcohol | 0.43 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 0.43 | 0.80 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 0.32 | 0.74 | |

| Cannabis users, lifetime | 4,569 | ||

| DSM-IV cannabis | 0.35 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 0.33 | 0.82 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 0.26 | 0.75 | |

| Cross-national emergency departments (54) | |||

| Drinkers, last 12 monthsa | 3,191 | ||

| DSM-IV alcohol | 0.21 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 0.21 | 0.80 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 0.15 | 0.79 | |

| Metropolitan clinical sample (N=663) (57) | |||

| Drinkers, last 12 monthsa | 534 | ||

| DSM-IV current alcohol | 46.9 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 48.7 | 0.94 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 45.7 | 0.96 | |

| DSM-5, ≥4 criteria | 42.8 | 0.92 | |

| Cannabis users, last 12 monthsa | 340 | ||

| DSM-IV cannabis | 21.1 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥ 2 criteria | 19.6 | 0.85 | |

| DSM-5, ≥ 3 criteria | 16.4 | 0.83 | |

| DSM-5, ≥ 4 criteria | 13.4 | 0.73 | |

| Cocaine users, last 12 monthsa | 483 | ||

| DSM-IV cocaine | 52.9 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 54.5 | 0.93 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 51.7 | 0.96 | |

| DSM-5, ≥4 criteria | 48.9 | 0.93 | |

| Heroin users, last 12 monthsa | 364 | ||

| DSM-IV heroin | 40.0 | ||

| DSM-5, ≥2 criteria | 41.6 | 0.95 | |

| DSM-5, ≥3 criteria | 39.2 | 0.97 | |

| DSM-5, ≥4 criteria | 36.5 | 0.96 | |

Any use within prior 12 months.

Concerns that the threshold of two or more criteria is too low have been expressed in the professional (93, 94) and lay press (95), at presentations, and on the DSM-5 web site (e.g., that it produces an overly heterogeneous group or that those at low severity levels are not “true” cases). These understandable concerns were weighed against the competing need to identify all cases meriting intervention, including milder cases, for example, those presenting in primary care. Table 3 shows that a concern that “millions more” would be diagnosed with the DSM-5 threshold (95) is unfounded if DSM-5 substance use disorder criteria are assessed and decision rules are followed (rather than assigning a substance use disorder diagnosis to any substance user). Additional concerns about the threshold should be addressed by indicators of severity, which clearly indicate that cases vary in severity.

An important exception to making a diagnosis of DSM-5 substance use disorder with two criteria pertains to the supervised use of psychoactive substances for medical purposes, including stimulants, cocaine, opioids, nitrous oxide, sedative-hypnotic/anxiolytic drugs, and cannabis in some jurisdictions (96, 97). These substances can produce tolerance and withdrawal as normal physiological adaptations when used appropriately for supervised medical purposes. With a threshold of two or more criteria, these criteria could lead to invalid substance use disorder diagnoses even with no other criteria met. Under these conditions, tolerance and withdrawal in the absence of other criteria do not indicate substance use disorders and should not be diagnosed as such.

DECISION: Set the diagnostic threshold for DSM-5 substance use disorders at two or more criteria.

How Should Severity Be Represented?

The DSM-5 Task Force asked work groups for severity indicators of diagnoses (mild, moderate, or severe). Many severity indicators are possible (e.g., levels of use, impairment, or comorbidity), and the Substance-Related Disorders Work Group sought a simple, parsimonious approach. A count of the criteria themselves serves this purpose well, since as the count increases so does the likelihood of substance use disorder risk factors and consequences (89–91, 98). The work group considered weighting the count by item response theory severity parameters, but comparing the association of weighted and unweighted criterion counts to consumption, functioning, and family history showed no advantage for weighting (98). Furthermore, since severity parameters differ somewhat across samples (31), no universal set of weights exists.

DECISION: Use a criteria count (from two to 11) as an overall severity indicator. Use number of criteria met to indicate mild (two to three criteria), moderate (four to five), and severe (six or more) disorders.

Specifiers

Physiological cases

DSM-IV included a specifier for physiological cases (i.e., those manifesting tolerance or withdrawal, a DSM-III carryover), but the predictive value of this specifier was inconsistent (99–106). A PubMed search indicated that this specifier was unused outside of studies investigating its validity, indicating negligible utility.

DECISION: Eliminate the physiological specifier in DSM-5.

Course

In DSM-IV, six course specifiers for dependence were provided. Four of these pertained to the time frame and completeness of remission, and two pertained to extenuating circumstances.

In DSM-IV, the specifiers for time frame and completeness of remission were complex and little used. To simplify, the work group eliminated partial remission and divided the time frame into two categories, early and sustained. Early remission indicates a period ≥3 months but <12 months without meeting DSM-5 substance use disorders criteria other than craving. Three months was selected because data indicated better outcomes for those retained in treatment at least this long (107, 108). Sustained remission indicates a period lasting ≥12 months without meeting DSM-5 substance use disorders criteria other than craving. Craving is an exception because it can persist long into remission (109, 110).

The work group noted that many clinical studies define remission and relapse in terms of substance use per se, not in terms of DSM criteria. The work group did not do this in order to remain consistent with DSM-IV criteria, and because the criteria focus on substance-related difficulties, not the extent of use, for the reasons discussed in the section on adding criteria. In addition, a lack of consensus on the level of use associated with a good outcome (111, 112) complicates substance use as a course specifier for the disorder.

The extenuating circumstance “in a controlled environment” was unchanged from DSM-IV. DSM-IV also included “on agonist therapy” (e.g., methadone or unspecified partial agonists or agonist/antagonists). To update this category, DSM-5 replaced it with “on maintenance therapy” and provided specific examples.

DECISION: Define early remission as ≥3 to <12 months without meeting substance use disorders criteria (except craving) and sustained remission as ≥12 months without meeting substance use disorders criteria (except craving). Update the maintenance therapy category with examples of agonists (e.g., methadone and buprenorphine), antagonists (e.g., naltrexone), and tobacco cessation medication (bupropion and varenicline).

Could the Definitions of Substance-Induced Mental Disorders Be Improved?

Substance use and other mental disorders frequently co-occur, complicating diagnosis because many symptoms (e.g., insomnia) are criteria for intoxication, withdrawal syndrome, or other mental disorders. Before DSM-IV, the nonstandardized substance-induced mental disorder criteria had poor reliability and validity. DSM-IV improved this (113) via standardized guidelines to differentiate between “primary” and “substance-induced” mental disorders. In DSM-IV, primary mental disorders were diagnosed if they began prior to substance use or if they persisted for more than 4 weeks after cessation of acute withdrawal or severe intoxication. DSM-IV substance-induced mental disorders were defined as occurring during periods of substance intoxication or withdrawal or remitting within 4 weeks thereafter. The symptoms listed for both the relevant disorder and for substance intoxication or withdrawal were counted toward the substance-induced mental disorder only if they exceeded the expected severity of intoxication or withdrawal. While severe consequences could accompany substance-induced mental disorders (114), remission was expected within days to weeks of abstinence (115–118).

Despite these clarifications, DSM-IV substance-induced mental disorders remained diagnostically challenging because of the absence of minimum duration and symptom requirements and guidelines on when symptoms exceeded expected severity for intoxication or withdrawal. In addition, the term “primary” was confusing, implying a time sequence or diagnostic hierarchy. Research showed that DSM-IV substance-induced mental disorders could be diagnosed reliably (113) and validly (119) by standardizing the procedures to determine when symptoms were greater than expected (although these were complex) and, importantly, by requiring the same duration and symptom criteria as the corresponding primary mental disorder. This evidence led to the DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work Group recommendation to increase standardization of the substance-induced mental disorder criteria by requiring that diagnoses have the same duration and symptom criteria as the corresponding primary diagnosis. However, concerns from the other DSM-5 work groups led the Board of Trustees to a flexible approach that reversed the DSM-IV standardization. This flexible approach lacked specific symptom and duration requirements and included the addition of disorder-specific approaches crafted by other DSM-5 work groups.

DECISIONS: 1) For a diagnosis of substance-induced mental disorder, add a criterion that the disorder “resembles” the full criteria for the relevant disorder. 2) Remove the requirement that symptoms exceed expected intoxication or withdrawal symptoms. 3) Specify that the substance must be pharmacologically capable of producing the psychiatric symptoms. 4) Change the name “primary” to “independent.” 5) Adjust “substance-induced” to “substance/medication-induced” disorders, since the latter were included in both DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria but not noted in the DSM-IV title.

Could Biomarkers Be Utilized in Making Substance Use Disorder Diagnoses?

Because of the DSM-5 Task Force interest in biomarkers, the Substance-Related Disorders Work Group, consulting with outside experts, considered pharmacokinetic measures of the psychoactive substances or their metabolites, genetic markers, and brain imaging indicators of brain structure and function.

Many measures of drugs and associated metabolites in blood, urine, sweat, saliva, hair, and breath have well-established sensitivity and specificity characteristics. However, these only indicate whether a substance was taken within a limited recent time window and thus cannot be used to diagnose substance use disorders.

Genetic variants within alcohol metabolizing genes (ALDH2, ADH1B, and ADH4), genes related to neurotransmission such as GABRA2 (120–122), and nicotinic and opioid receptor genes including CHRNA5 (120) and OPRM1 (123) show replicated associations to substance use disorders. However, these associations have small effects or are rare in many populations and thus cannot be used in diagnosis. Perhaps in future editions, DSM may include markers as predictors of treatment outcome (e.g., OPRM1 A118G and naltrexone response [124, 125])

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of brain functioning indicates that dopamine is associated with substance use (126, 127). However, measuring brain dopamine markers involves radioligands, limiting their use. Functional MRI (fMRI) produces structural and functional data, but few fMRI or PET studies have differentiated brain functioning predating and consequent to onset of substance use disorders (128). Furthermore, brain imaging findings based on group differences are not specific enough to use as diagnostic markers in individual cases. Finally, abnormalities in brain regions and functioning that are associated with substance use disorders overlap with other psychiatric disorders. In sum, biomarkers are not yet appropriate as diagnostic tests for substance use disorders. Continued research in this area is important.

DECISION: Do not include biomarkers.

Should Polysubstance Dependence Be Retained?

In DSM-IV, polysubstance dependence allowed diagnosis for multiple-substance users who failed to meet dependence criteria for any one substance but had three or more dependence criteria collectively across substances. The category was often misunderstood as dependence on multiple substances and was little used (129). With the new threshold for DSM-5 substance use disorders (two or more criteria), the category became irrelevant.

DECISION: Eliminate polysubstance dependence.

Substance-Specific Issues

Should Cannabis, Caffeine, Inhalant, and Ecstasy Withdrawal Disorders Be Added?

Cannabis

Cannabis withdrawal was not included in DSM-IV because of a lack of evidence. Since then, the reliability and validity of cannabis withdrawal has been demonstrated in preclinical, clinical, and epidemiological studies (126, 127, 130–135). The syndrome has a transient course after cessation of cannabis use (135–138) and pharmacological specificity (139–141). Cannabis withdrawal is reported by up to one-third of regular users in the general population (131, 132, 134) and by 50%–95% of heavy users in treatment or research studies (133, 135, 142, 143). The clinical significance of cannabis withdrawal is demonstrated by use of cannabis or other substances to relieve it, its association with difficulty quitting (135, 142, 144), and worse treatment outcomes associated with greater withdrawal severity (133, 143). In addition, in latent variable modeling (30), adding withdrawal to other substance use disorders criteria for cannabis improves model fit.

Inhalants/hallucinogens

While some support exists for adding withdrawal syndromes for inhalants and Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) (31, 145–147), the literature and expert consultation suggest that evidence remains insufficient to include these in DSM-5, but further study is warranted.

Caffeine

In DSM-IV, caffeine withdrawal was included as a research diagnosis to encourage research (148). The accumulated evidence from preclinical and clinical studies since the publication of DSM-IV supports the reliability, validity, pharmacological specificity, and clinical significance of caffeine withdrawal (149–152). Based on factor analysis studies, the work group proposed modifying the DSM-IV research criteria so that a diagnosis in DSM-5 would require three or more of the following symptoms: 1) headache; 2) fatigue or drowsiness; 3) dysphoric mood or irritability; 4) difficulty concentrating; and 5) nausea, vomiting, or muscle pain/stiffness (153, 154).

DSM-IV did not include caffeine dependence despite preclinical research literature because clinical data were lacking (155). Relatively small-sample clinical surveys published since then and the accumulating data on the clinical significance of caffeine withdrawal and dependence support further consideration for a caffeine use disorder (152, 153, 156–160), particularly given concerns about youth energy drink misuse and new alcohol-caffeine combination beverages (161, 162). However, clinical and epidemiological studies with larger samples and more diverse populations are needed to determine prevalence, establish a consistent set of diagnostic criteria, and better evaluate the clinical significance of a caffeine use disorder. These studies should address test-retest reliability and antecedent, concurrent, and predictive validity (e.g., distress and impaired functioning).

DECISIONS: 1) Add cannabis withdrawal disorder. Include withdrawal as a criterion for cannabis use disorder. 2) Add caffeine withdrawal disorder, and include caffeine use disorder in Section 3 (“Conditions for Further Study”).

Could the Nicotine Criteria Be Aligned With the Diagnostic Criteria for the Other Substance Use Disorders?

DSM-IV included nicotine dependence, but experts felt that abuse criteria were inapplicable to nicotine (163, 164), so these were not included. Nicotine dependence has good test-retest reliability (165–167) and its criteria indicate a unidimensional latent trait (39, 40, 62, 67, 168). Concerns about DSM-IV-defined nicotine dependence include the utility of some criteria, the ability to predict treatment outcome, and low prevalence in smokers (131, 163, 169). Many studies therefore indicate nicotine dependence with an alternative measure, the Fagerström Nicotine Dependence Scale (170, 171). DSM-IV and the Fagerström scale measure somewhat different aspects of a common underlying trait (67, 168, 172).

Because DSM-5 combines dependence and abuse, studies addressed whether criteria for nicotine use disorder could be aligned with other substance use disorders (45, 71, 181), potentially also addressing the concerns about DSM-IV-defined nicotine dependence. Smoking researchers widely regard craving as an indicator of dependence and relapse (164, 173–175). Increasing disapproval of smoking (176) and wider smoking restrictions (177) suggest improved face validity of continued smoking despite interpersonal problems and smoking-related failure to fulfill responsibilities as tobacco use disorder criteria. Smoking is highly associated with fire-related and other mortality (e.g., unintentional injuries and vehicle crashes) (173, 178–180), suggesting the applicability of hazardous use as a criterion for tobacco use disorders, parallel with hazardous use of other substances.

To examine the alignment of criteria for tobacco use disorder with those for other substance use disorders, an item response theory analysis of the seven dependence criteria, three abuse criteria, and craving was performed in a large adult sample of smokers (45). The 11 criteria formed a unidimensional latent trait intermixed across the severity spectrum, significantly increasing information over a model using DSM-IV nicotine dependence criteria only. Differential item functioning was found for craving and hazardous use, but differential total score functioning was not found. The proposed tobacco use disorder criteria (individually and as a set) were strongly associated with a panel of validators, including smoking quantity and smoking shortly after awakening (181). The tobacco use disorder criteria were more discriminating than the DSM-IV nicotine dependence criteria (181) and produced a higher prevalence than DSM-IV criteria, addressing a DSM-IV concern (163). An item response theory secondary analysis of 10 of the 11 criteria from adolescent and young adult substance abuse patients (71) also revealed unidimensionality and a higher prevalence of DSM-5 tobacco use disorder than DSM-IV nicotine dependence (71).

DECISION: Align DSM-5 criteria for tobacco use disorder with criteria for the other substance use disorders.

Should Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated With Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Be Added?

In utero alcohol exposure acts as a neurobehavioral teratogen, with lifelong effects on CNS function and behavior (182, 183). These effects are now known as neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Key features include neurocognitive and behavioral impairments (184) diagnosed through standardized psychological or educational testing, caregiver/teacher questionnaires, medical records, reports from the patient or a knowledgeable informant, or clinician observation. Prenatal alcohol exposure can be determined by maternal self-report, others’ reported observations of maternal drinking during the pregnancy, and documentation in medical or other records.

Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure was not included in DSM-IV. The proposed diagnostic guidelines allow this diagnosis regardless of the facial dysmorphology required to diagnose fetal alcohol syndrome (185). Many clinical experts support the diagnosis (186), and clinical need is suggested by substantial misdiagnosis, leading to unmet treatment need (186). However, more information is needed on this disorder before it can be included in the main diagnosis section of the manual.

DECISION: Include neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in Section 3.

Issues Not Related To Substances

Should Gambling Disorder and Other Putative Behavioral “Addictions” Be Added to the Substance Disorders Chapter?

Gambling

In DSM-IV, pathological gambling is in the section entitled “Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified.” Pathological gambling is comorbid with substance use disorders (187–189) and is similar to substance use disorders in some symptom presentations (190), biological dysfunction (191), genetic liability (192), and treatment approaches (193–195). The work group therefore concurred with a DSM-5 Task Force request to move pathological gambling to the substance use disorders chapter. The work group also recommended other modifications (196). The name will be changed to “Gambling Disorder” because the term pathological is pejorative and redundant. The criterion “illegal acts to finance gambling” was removed for the same reasons that legal problems were removed from substance use disorders (197–200; B. Grant, unpublished 2010 data). The diagnostic threshold was reduced to four or more criteria to improve classification accuracy (200–203). A further reduction in the threshold was considered, but this greatly increased prevalence (189, 197) without evidence for diagnostic improvement. Future research should explore whether gambling disorder can be assessed using criteria that are parallel to those for substance use disorders (200).

Other non-substance-related disorders

The work group consulted outside experts and reviewed literature on other potential non-substance-related behaviors (e.g., Internet gaming and shopping). This included over 200 publications on Internet gaming addiction, mostly Asian case reports or series of young males. Despite the large literature (204–207), no standard diagnostic criteria and only limited data were available on prevalence, course, or brain functioning. Therefore, research is needed to ascertain the unique characteristics of the disorder, the cross-cultural reliability and validity data of diagnostic criteria, prevalence in representative samples, natural history, and potentially associated biological factors (196). Research on other behavioral addictions is even more preliminary. Disorders involving sexual behaviors or eating were handled by other work groups.

DECISION: Include gambling disorder in the substance use disorders section, with changes noted above. Add Internet gaming disorder to Section 3.

Should the Name of the Chapter Be Changed?

With the addition of gambling disorder to the chapter, a change in the title was necessary. The Board of Trustees assigned the title “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders,” despite the DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work Group having previously approved a title (by majority but not consensus) that did not include the term addiction. This lack of agreement over the title reflects an overall tension in the field over the terms addiction and dependence, as seen in editorials (2, 208) advocating addiction as a general term, reserving dependence specifically for tolerance and/or withdrawal, and the more than 80 comments on these editorials that debated the pros and cons of these terms.

Present Status and Future Directions

Since 2007, the Substance-Related Disorders Work Group addressed many issues. The members conducted and published analyses, and they formulated new criteria and presented them widely for input. The DSM-5 Task Force requested a reduction in the number of disorders wherever possible, and the work group accomplished this.

The DSM process requires balancing many competing needs, which is always the case when formulating new nomenclatures. The process also entails extensive, unpaid collaboration among a group of experts with different backgrounds and perspectives. Scientific controversies arose and received responses (see references 2, 47, and 209–211). Conflict of interest could undermine confidence in the work group’s recommendations (212), but in fact, as monitored by APA, eight of the 12 members received no pharmaceutical industry income over the 5 years since the work group was convened, two received less than $1,200 and two received less than $10,000 (the APA cap) in any single year. Some individuals assume that financial interests advocated directly to the work group (e.g., pharmaceutical companies, alcohol and tobacco industries, insurers, and providers). Actually, this never happened. While such advocacy could have occurred surreptitiously through unsigned DSM-5 web site comments, few comments stood out as particularly influential since they covered such a wide range of opinions. An exception to this was the web site advocacy of nonprofit groups to include neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (taken into account in forming the disorder recommendation). Ultimately, the work group recommendations attracted considerable interest, and the DSM-5 process stimulated much substance use disorder research that otherwise would not have occurred.

Implementing the 11 DSM-5 substance use disorders criteria in research and clinical assessment should be easier than implementing the 11 DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse and dependence, since now only one disorder is involved instead of two hierarchical disorders. A checklist can aid in covering all criteria. Eventually, reducing the number of criteria to diagnose substance use disorders will further aid implementation, which future studies should address.

The statistical methodology used to examine the structure of abuse and dependence criteria was state of the art, and the data sets analyzed were large and based on standardized diagnostic procedures with good to excellent reliability and validity. However, these data sets, collected several years ago, were not designed to examine the reliability and validity of the DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnosis. Many studies showed that DSM-IV dependence was reliable and valid (5), suggesting that major components of the DSM-5 substance use disorders criteria are reliable as well. However, field trials using standard methodology to minimize information variance (213) are needed to provide information on the reliability of DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnosis that can be directly compared with DSM-IV (214), in addition to studies on the antecedent, concurrent, and predictive validity of DSM-5 substance use disorders relative to DSM-IV dependence.

The amount of data available to address the topics discussed above varied, and new studies will be needed for some of the more specific issues. However, major concerns regarding the combination of abuse and dependence criteria were conclusively addressed because an astonishing amount of data was available and the results were very consistent. The recommendations for DSM-5 substance use disorders represent the results of a lengthy and intensive process aimed at identifying problems in DSM-IV and resolving these through changes in DSM-5. At the same time, the variable amount of evidence on some of the issues points the way toward studies aimed at further clarifications and improvements in future editions of DSM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Auriacombe has received research grants or advisory board fees from D&A Pharma, Mundipharma, and Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Budney has received consulting fees from G.W. Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Compton has stock holdings in General Electric and Pfizer. Dr. Ling has received consulting fees or research, grant, or travel support from Alkermes, Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, Reckitt/Benckiser, Titan Pharmaceuticals, U.S. World Meds, and SGS North America.

Supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants K05AA014223, U01AA018111), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA018652), and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (to Dr. Hasin).

The authors thank Katherine M. Keyes, Nick Giedris, and Dvora Shmulewitz for help in preparing the manuscript and Ray Anton, Robert Balster, Deborah Dawson, Danielle Dick, Joel Gelernter, Marilyn Huestis, John Hughes, Tom Kosten, Henry Kranzler, Tulshi Saha, Wim van den Brink, and Nora Volkow for their expert input.

Footnotes

The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the U.S. government.

References

- 1.Special issue: diagnostic issues in substance use disorders: refining the research agenda. Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien C. Addiction and dependence in DSM-V. Addiction. 2011;106:866–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. BMJ. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rounsaville BJ, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Proposed changes in DSM-III substance use disorders: description and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:463–468. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson DA. Drinking patterns among individuals with and without DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierucci-Lagha A, Gelernter J, Feinn R, Cubells JF, Pearson D, Pollastri A, Farrer L, Kranzler HR. Diagnostic reliability of the Semi-structured Assessment for Drug Dependence and Alcoholism (SSADDA) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasin D, Paykin A. DSM-IV alcohol abuse: investigation in a sample of at-risk drinkers in the community. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:181–187. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasin D, Paykin A, Endicott J, Grant B. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse: drunk drivers versus all others. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:746–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasin DS, Grant B, Endicott J. The natural history of alcohol abuse: implications for definitions of alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1537–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasin DS, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Differentiating DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: community heavy drinkers. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Landi NA. The 5-year clinical course of high-functioning men with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:2028–2035. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuckit MA, Smith TL. A comparison of correlates of DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence among more than 400 sons of alcoholics and controls. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasin DS, Hatzenbueler M, Smith S, Grant BF. Co-occurring DSM-IV drug abuse in DSM-IV drug dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasin DS, Grant BF. The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:891–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant BF, Compton WM, Crowley TJ, Hasin DS, Helzer JE, Li TK, Rounsaville BJ, Volkow ND, Woody GE. Errors in assessing DSM-IV substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:379–380. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.379. author reply 381–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic “orphans” in a community sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: diagnostic “orphans” in a 1992 national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollock NK, Martin CS. Diagnostic orphans: adolescents with alcohol symptom who do not qualify for DSM-IV abuse or dependence diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:897–901. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBride O, Adamson G, Bunting BP, McCann S. Characteristics of DSM-IV alcohol diagnostic orphans: drinking patterns, physical illness, and negative life events. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krueger RF, Nichol PE, Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Using latent trait modeling to conceptualize an alcohol problems continuum. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:107–119. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasin DS, Muthuen B, Wisnicki KS, Grant B. Validity of the biaxial dependence concept: a test in the US general population. Addiction. 1994;89:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proudfoot H, Baillie AJ, Teesson M. The structure of alcohol dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harford TC, Muthén BO. The dimensionality of alcohol abuse and dependence: a multivariate analysis of DSM-IV symptom items in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:150–157. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Factor and item-response analysis DSM-IV criteria for abuse of and dependence on cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants and opioids. Addiction. 2007;102:920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teesson M, Lynskey M, Manor B, Baillie A. The structure of cannabis dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanco C, Harford TC, Nunes E, Grant B, Hasin D. The latent structure of marijuana and cocaine use disorders: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant BF, Harford TC, Muthén BO, Yi HY, Hasin DS, Stinson FS. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse: further evidence of validity in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha TD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynskey MT, Agrawal A. Psychometric properties of DSM assessments of illicit drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Psychol Med. 2007;37:1345–1355. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Compton WM, Saha TD, Conway KP, Grant BF. The role of cannabis use within a dimensional approach to cannabis use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McBride O, Strong DR, Kahler CW. Exploring the role of a nicotine quantity-frequency use criterion in the classification of nicotine dependence and the stability of a nicotine dependence continuum over time. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:207–216. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saha TD, Compton WM, Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Grant BF. Dimensionality of DSM-IV nicotine dependence in a national sample: an item response theory application. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Beseler C, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychol Med. 2011;41:629–640. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Smith S, Chou PS, Pickering RP, Huang B, Ruan JW, Pulay AJ. Dimensionality of hallucinogen and inhalant/solvent abuse and dependence criteria: implications for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. Addict Behav. 2011;36:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saha TD, Compton WM, Chou SP, Smith S, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Pickering RP, Grant BF. Analyses related to the development of DSM-5 criteria for substance use related disorders: 1. Toward amphetamine, cocaine and prescription drug use disorder continua using item response theory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shmulewitz D, Keyes KM, Wall MM, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, Spivak B, Weizman A, Frisch A, Grant BF, Hasin D. Nicotine dependence, abuse and craving: dimensionality in an Israeli sample. Addiction. 2011;106:1675–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Pan JJ, Blazer DG. Abuse and dependence on prescription opioids in adults: a mixture categorical and dimensional approach to diagnostic classification. Psychol Med. 2011;41:653–664. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mewton L, Slade T, McBride O, Grove R, Teesson M. An evaluation of the proposed DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria using Australian national data. Addiction. 2011;106:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilder DA, Gizer IR, Ehlers CL. Item response theory analysis of binge drinking and its relationship to lifetime alcohol use disorder symptom severity in an American Indian community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:984–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casey M, Adamson G, Shevlin M, McKinney A. The role of craving in AUDs: dimensionality and Differential Functioning in the DSM-5. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Pan JJ, Reeve BB, Blazer DG. A dimensional approach to understanding severity estimates and risk correlates of marijuana abuse and dependence in adults. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:117–133. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu LT, Pan JJ, Blazer DG, Tai B, Brooner RK, Stitzer ML, Patkar AA, Blaine JD. The construct and measurement equivalence of cocaine and opioid dependences: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu LT, Pan JJ, Blazer DG, Tai B, Stitzer ML, Brooner RK, Woody GE, Patkar AA, Blaine JD. An item response theory modeling of alcohol and marijuana dependences: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:414–425. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpitel CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Rubio-Stipec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borges G, Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Threshold and optimal cut-points for alcohol use disorders among patients in the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1270–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCutcheon VV, Agrawal A, Heath AC, Edenberg HJ, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Kramer JR, Bucholz KK. Functioning of alcohol use disorder criteria among men and women with arrests for driving under the influence of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1985–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasin DS, Fenton MC, Beseler C, Park JY, Wall MM. Analyses related to the development of DSM-5 criteria for substance use related disorders: 2. Proposed DSM-5 criteria for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and heroin disorders in 663 substance abuse patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harford TC, Yi HY, Faden VB, Chen CM. The dimensionality of DSM-IV alcohol use disorders among adolescent and adult drinkers and symptom patterns by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strong DR, Kahler CW, Colby SM, Griesler PC, Kandel D. Linking measures of adolescent nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Yang C, Reeve BB, Pan JJ, Blazer DG. Construct and differential item functioning in the assessment of prescription opioid use disorders among American adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:563–572. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819e3f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beseler CL, Taylor LA, Leeman RF. An item-response theory analysis of DSM-IV alcohol-use disorder criteria and “binge” drinking in undergraduates. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:418–423. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rose JS, Dierker LC. DSM-IV nicotine dependence symptom characteristics for recent-onset smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:278–286. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu LT, Pan JJ, Yang C, Reeve BB, Blazer DG. An item response theory analysis of DSM-IV criteria for hallucinogen abuse and dependence in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2010;35:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagman BT, Cohn AM. Toward DSM-V: mapping the alcohol use disorder continuum in college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mewton L, Teesson M, Slade T, Cottler L. Psychometric performance of DSM-IV alcohol use disorders in young adulthood: evidence from an Australian general population sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:811–822. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piontek D, Kraus L, Legleye S, Bühringer G. The validity of DSM-IV cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in adolescents and the value of additional cannabis use indicators. Addiction. 2011;106:1137–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strong DR, Schonbrun YC, Schaffran C, Griesler PC, Kandel D. Linking measures of adult nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum and a comparison with adolescent patterns. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Stallings M, Young S, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt J, Hopfer C, Crowley T. Toward DSM-V: an item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1329–1339. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartman CA, Gelhorn H, Crowley TJ, Sakai JT, Stallings M, Young SE, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ. Item response theory analysis of DSM-IV cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:165–173. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perron BE, Vaughn MG, Howard MO, Bohnert A, Guerrero E. Item response theory analysis of DSM-IV criteria for inhalant-use disorders in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:607–614. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung T, Martin CS, Maisto SA, Cornelius JR, Clark DB. Greater prevalence of proposed DSM-5 nicotine use disorder compared to DSM-IV nicotine dependence in treated adolescents and young adults. Addiction. 2012;107:810–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization. ATLAS on substance use: (2010): resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. ( http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/treatment/en/index.html) [Google Scholar]

- 73.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drug Report 2009. United Nations: 2009. ( http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2009/WDR2009_eng_web.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. ( http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lagenbucher JW. Alcohol abuse: adding content to category. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(suppl):270A–275A. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Svanum S. Alcohol-related problems and dependence: an elaboration and integration. Int J Addict. 1986;21:539–558. doi: 10.3109/10826088609083540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perkins KA. Chronic tolerance to nicotine in humans and its relationship to tobacco dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:405–422. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000018425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miller NS, Goldsmith RJ. Craving for alcohol and drugs in animals and humans: biology and behavior. J Addict Dis. 2001;20:87–104. doi: 10.1300/J069v20n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heinz A, Beck A, Grüsser SM, Grace AA, Wrase J. Identifying the neural circuitry of alcohol craving and relapse vulnerability. Addict Biol. 2009;14:108–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH. Cue-provoked craving and nicotine replacement therapy in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1136–1143. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]