Abstract

CD73 inhibits antitumor immunity through the activation of adenosine receptors expressed on multiple immune subsets. CD73 also enhances tumor metastasis, although the nature of the immune subsets and adenosine receptor subtypes involved in this process are largely unknown. In this study, we revealed that A2A/A2B receptor antagonists were effective in reducing the metastasis of tumors expressing CD73 endogenously (4T1.2 breast tumors) and when CD73 was ectopically expressed (B16F10 melanoma). A2A−/− mice were strongly protected against tumor metastasis, indicating that host A2A receptors enhanced tumor metastasis. A2A blockade enhanced natural killer (NK) cell maturation and cytotoxic function in vitro, reduced metastasis in a perforin-dependent manner, and enhanced NK cell expression of granzyme B in vivo, strongly suggesting that the antimetastatic effect of A2A blockade was due to enhanced NK cell function. Interestingly, A2B blockade had no effect on NK cell cytotoxicity, indicating that an NK cell-independent mechanism also contributed to the increased metastasis of CD73+ tumors. Our results thus revealed that CD73 promotes tumor metastasis through multiple mechanisms, including suppression of NK cell function. Furthermore, our data strongly suggest that A2A or A2B antagonists may be useful for the treatment of metastatic disease. Overall, our study has potential therapeutic implications given that A2A/A2B receptor antagonists have already entered clinical trials in other therapeutic settings.

Keywords: cancer metastasis, immunotherapy, tumor immunosuppression, innate immunity

It is now well-established that tumors use numerous immunosuppressive mechanisms to facilitate tumor growth (1, 2). Landmark studies by Sitkovsky and colleagues established that one such mechanism is the catabolism of extracellular AMP into immunosuppressive adenosine (3, 4). Extracellular adenosine is generated from adenosine monophosphate (AMP) by the ectoenzyme CD73 and binds to four known cell surface receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) that are expressed on multiple immune subsets including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (5). The A2A and A2B receptor subtypes are essentially responsible for the immunosuppressive effects of adenosine. They share a common signaling pathway, both resulting in the activation of adenylate cyclase and the accumulation of intracellular cAMP. Extracellular AMP can be generated from ATP, an immune-activating molecule, by the ectoenzyme CD39. Thus, CD73 and CD39 acting in concert can catabolize ATP into adenosine and therefore tip the balance from an immunostimulatory to an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Physiologically, CD73 is expressed on endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and subsets of the immune system, including Tregs (5). CD73 has been found to be up-regulated in several types of cancer and recently it has been shown to be a negative prognostic marker in triple negative breast cancer (5, 6). Several preclinical studies indicate that targeting the CD73-adenosine pathway may be beneficial. Proof-of-concept studies demonstrated that targeting CD73 with an anti-CD73–blocking mAb could significantly delay tumor growth (7). This was due to enhanced antitumor immune T-cell responses as a result of attenuated A2A-mediated immunosuppression. Subsequently, both host and tumor-expressed CD73 have been shown to be important in the suppression of antitumor T-cell responses. Indeed, CD73-deficient mice are resistant to several transplantable tumors and de novo carcinogenesis (8–11). On the other hand, specific targeting of CD73 on tumor cells using shRNA also significantly reduced tumor growth and prolonged survival (7, 12).

Furthermore, the knockdown of CD73 expression on tumor cells reduced their ability to metastasize (7). However, the mechanism by which CD73 promotes tumor metastasis is unclear. Understanding the mechanism by which CD73 increases tumor metastasis is vital to developing new strategies that target metastasis because there are no anti-CD73 mAbs currently in clinical development. The clinical relevance of this pathway is underlined by the correlation between CD73 expression and an increased risk of metastasis in breast cancer (13, 14). Thus, the CD73 pathway has been proposed as a novel target for immunotherapy (15).

In this current study, we found that CD73 promoted metastasis through the activation of both A2A and A2B receptors. A2A blockade resulted in enhanced NK-cell activity in vitro and in vivo and reduced metastasis in a perforin-dependent manner. Thus, A2A or A2B antagonists, which have already been used in clinical trials in other disease settings (16), are promising for the treatment of cancer metastasis for which there is a lack of effective options available.

Results

Tumor-CD73 Expression Promotes in Vivo Metastasis.

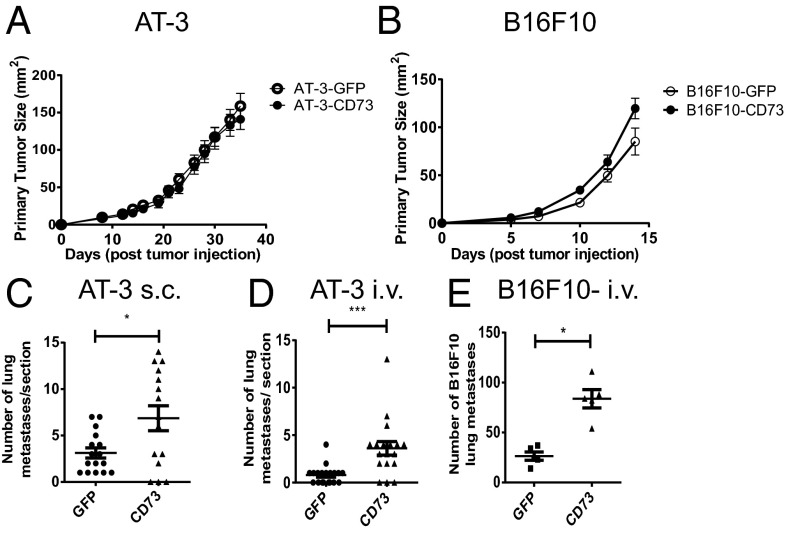

Previous investigations in our laboratory suggested that the expression of CD73 on tumor cells could positively regulate metastasis (7). To investigate whether CD73 expression was sufficient to increase the migratory properties of tumor cells, AT-3 breast adenocarcinoma and B16F10 melanoma cells (both CD73−) were transduced with retrovirus-encoding murine CD73 cDNA. CD73 expression on transduced AT-3 and B16F10 cells was at a level equivalent to 4T1.2 breast carcinoma cells, a metastatic cell line expressing high levels of CD73 (Fig. S1A) (7). Ectopically expressed CD73 was enzymatically active as shown by the conversion of AMP to adenosine (Fig. S1B). Despite the fact that ectopic CD73 expression did not modulate primary tumor growth of AT-3 (Fig. 1A) or B16F10 tumors (Fig. 1B), it significantly enhanced pulmonary metastasis when AT-3 cells were injected either s.c. (spontaneous metastasis) (Fig. 1C) or i.v. (experimental metastasis) (Fig. 1D), and significantly promoted the experimental metastasis of B16F10 melanoma cells (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

CD73 expression enhances spontaneous and experimental metastasis of tumor cells. (A) A total of 5 × 105 AT-3-GFP/AT-3-CD73 cells or (B) 1 × 105 B16F10-GFP/B16F10-CD73 cells were injected s.c. into WT mice and primary tumor growth compared. Results shown are the mean ± SD of five mice of a representative experiment of n = 4. (C) At day 37 after s.c. injection of AT-3-GFP/AT-3-CD73 cells, lungs were harvested and sectioned. (D) A total of 5 × 105 AT-3-GFP/AT-3-CD73 cells or (E) 2 × 105 B16F10-GFP/B16F10-CD73 cells were injected i.v. into WT mice and lungs harvested 14 d after tumor inoculation. (C and D) Results shown are the mean ± SEM of pooled data from three individual experiments. (E) Results shown are the mean ± SD of five mice from a representative experiment of n = 5. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Activation of A2A Adenosine Receptors Enhances Metastasis Through Suppression of the Antitumor Immune Response.

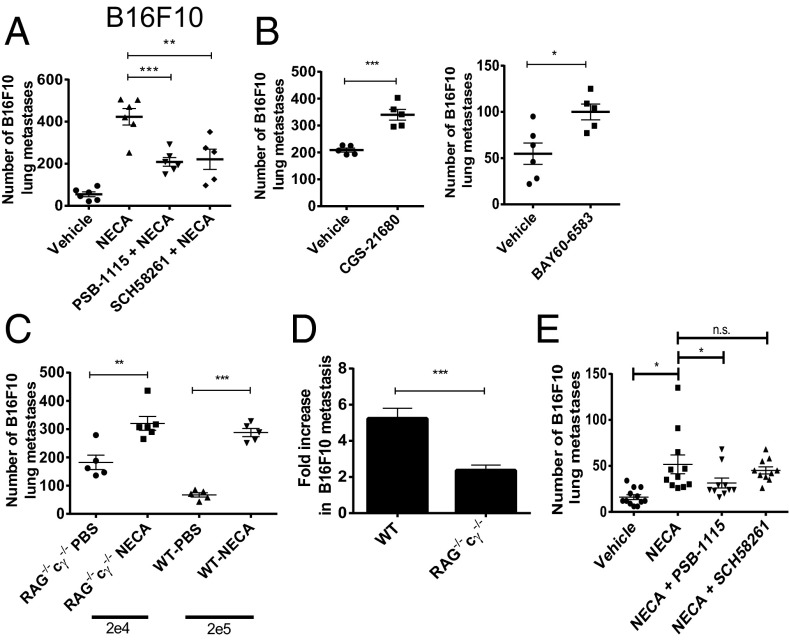

We next examined the effect of 5′-(N-ethylcarboxamido)adenosine (NECA), a pan adenosine receptor agonist, on tumor metastasis to determine whether the prometastatic effect of CD73 could be replicated by adenosine receptor stimulation. NECA pretreatment was found to significantly increase the metastasis of B16F10 melanoma cells in WT mice (Fig. 2A). The increased metastasis following NECA treatment of WT mice could be partially reversed with either PSB-1115 (an adenosine receptor A2B antagonist) or SCH58261 (an adenosine receptor A2A antagonist) (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the activation of both A2A and A2B receptors was contributing to the prometastatic effect of NECA. To provide further evidence to support a prometastatic role for the A2A and A2B receptors, mice were treated with either CGS-21680, an A2A receptor agonist, or BAY60-6583, an A2B receptor agonist, before injection of B16F10 tumor cells. Both CGS-21680 and BAY60-6583 enhanced B16F10 lung metastasis (Fig. 2B). Because stimulation of both A2A and A2B receptors is known to induce immunosuppressive effects, we investigated whether activation of these receptors affected metastasis in immunocompromised mice. Pretreatment of both WT and RAG−/−cγ−/− mice with NECA resulted in significantly enhanced metastasis (Fig. 2C), although the effect appeared less marked in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice. Indeed, the fold increase in metastasis induced by NECA was significantly less in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, A2A blockade did not affect the increase in metastasis induced by NECA in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results indicate that the prometastatic effect of NECA was partly immune-dependent and that the reduction in metastasis following A2A blockade in WT mice was dependent on enhanced function of immune cells deficient in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice. Conversely A2B blockade reversed the increase in metastasis mediated by NECA in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice, indicating a distinct mechanism underpinning the antimetastatic effect of A2B blockade.

Fig. 2.

Activation of either the A2A or A2B adenosine receptors increases tumor metastasis. (A–D) WT or (C–E) RAG−/−cγ−/− mice were pretreated i.p. with either PSB-1115 (1 mg/kg), SCH58261 (1 mg/kg), or vehicle control before treatment with NECA (0.05 mg/kg), CGS-21680 (2 mg/kg), BAY-60-6583 (0.1 mg/kg), or PBS. One hour posttreatment, mice were injected i.v. with 2 × 105 (WT), 2 × 104 (RAG−/−cγ−/−: C and D), or 1 × 104 (RAG−/−cγ−/−: E) B16F10 GFP tumor cells. (A–C) Data shown are the mean ± SD from one experiment of n = 3. (D) Data are represented as the mean (n = 16) ± SEM fold increase in metastasis induced by NECA in WT and RAG−/−cγ−/− mice relative to PBS-treated controls. (E) Results shown are the mean ± SEM pooled from two individual experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s., not significant.

Blockade of Either A2A or A2B Adenosine Receptors Inhibits the Metastasis of CD73+ Tumors.

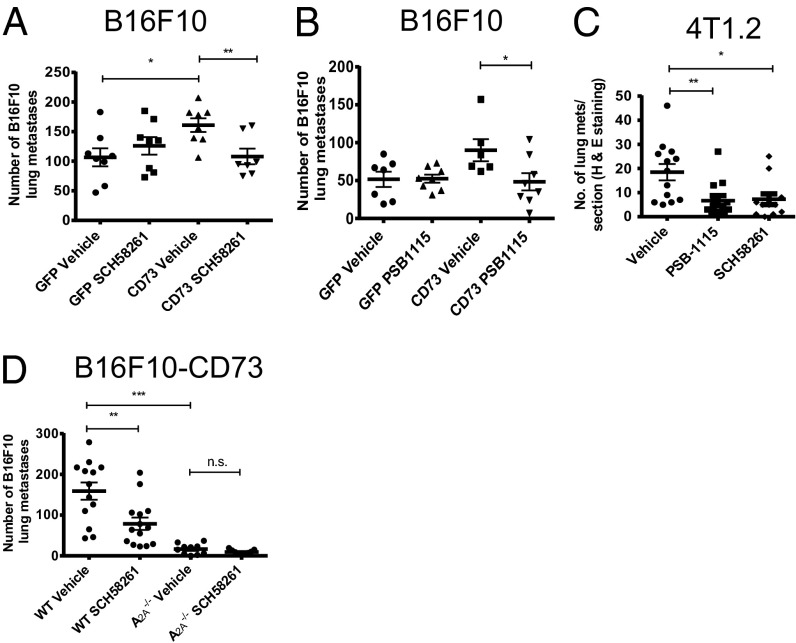

Having shown that the prometastatic effects of NECA could be partially reversed via antagonism of A2A or A2B receptors, we investigated whether this was relevant to the enhanced metastasis of CD73+ B16F10 tumors. A2A or A2B receptor blockade, with SCH58261 or PSB-1115, respectively, significantly reduced the metastasis of B16F10 CD73+ tumors but not B16F10 GFP+ control tumors (Fig. 3 A and B). This data strongly suggested that the activation of A2A and A2B receptors is important in the increased metastatic phenotype of CD73+ B16F10 cells. Having demonstrated that blockade of A2A or A2B receptors could suppress the metastasis of B16F10 CD73+ tumors, we determined whether these treatment strategies were as effective in preventing spontaneous metastases. To investigate this, we used the 4T1.2 tumor model, a highly metastatic breast cancer line known to express CD73 endogenously. Treatment of mice with either an A2A antagonist (SCH58261) or an A2B antagonist (PSB-1115) significantly reduced the metastasis of 4T1.2 tumors compared with vehicle control-treated mice (Fig. 3C), further implicating A2A and A2B receptor activation as a prometastatic mechanism. To confirm that the effects of SCH58261 were attributable to blockade of the A2A receptor, we investigated the metastasis of B16F10 CD73+ tumor cells in WT and A2A−/− mice. A2A−/− mice were significantly protected from the metastasis of B16F10 CD73+ tumor cells (Fig. 3D). These data support the hypothesis that A2A blockade was acting on host immune cells and not on the tumor cells that also express A2A receptors. Moreover, the A2A antagonist SCH58261 was ineffective in A2A−/− mice, confirming the specificity of this compound.

Fig. 3.

Blockade of A2A or A2B receptors with selective antagonists significantly reduces the metastasis of CD73+ tumors. WT mice were pretreated with (A) SCH58261 (1 mg/kg), (B) PSB-1115 (1 mg/kg), or vehicle control at days 0 (−1 h), 1, and 7 and injected i.v. with 2 × 105 B16F10-GFP or B16F10-CD73 tumor cells. Results shown are the mean ± SD of a representative experiment of n = 3. (C) 4T1.2 tumor cells were injected into the fourth mammary fat pad at a dose of 5 × 104. Mice were treated with either vehicle control, SCH58261 (1 mg/kg), or PSB-1115 (1 mg/kg) three times per week with therapy initiated on day 3. After 30 d, lungs were harvested and sectioned and metastases determined. Results shown are the mean ± SEM of n = 12 pooled from two individual experiments. (D) WT or A2A−/− mice treated with vehicle or SCH58261 (1 mg/kg) at days 0 (−1 h), 1, and 7 and injected i.v. with 2 × 105 B16F10 CD73+ cells. Results shown are the mean ± SEM pooled from two individual experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

A2A Blockade Reduces Metastasis Through Enhanced NK Cell Function.

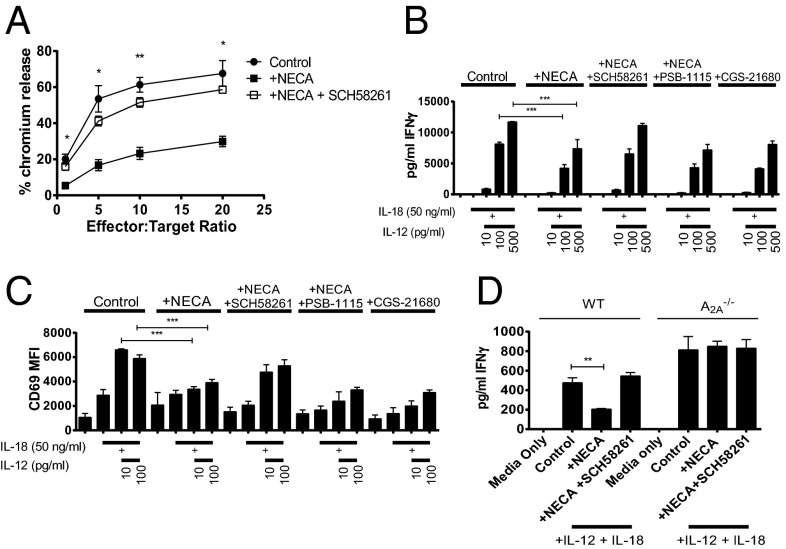

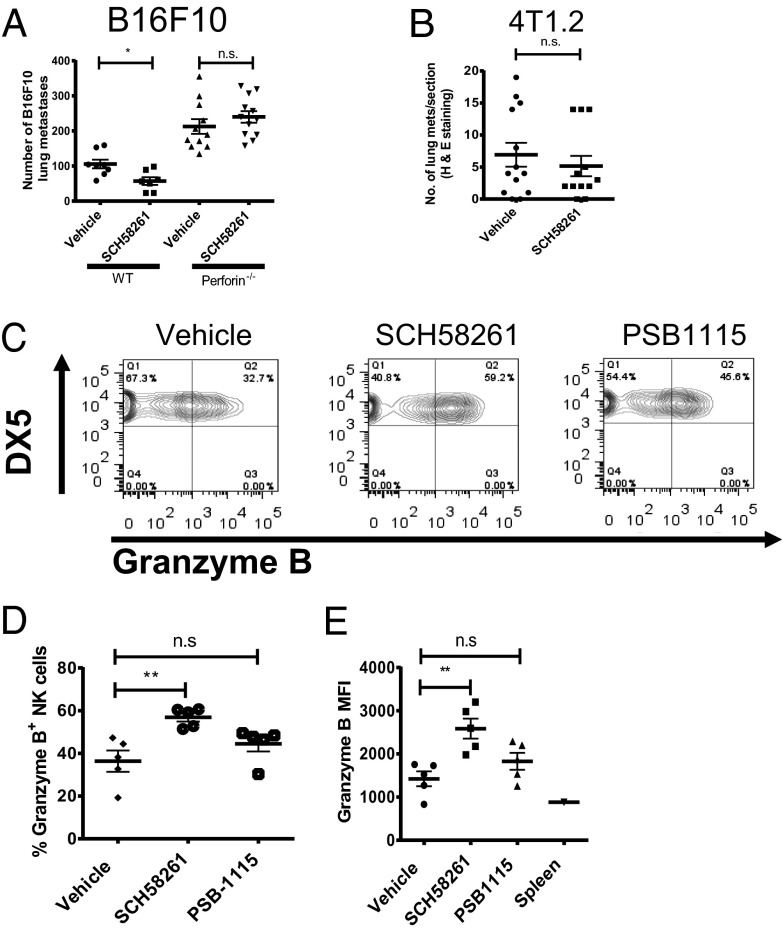

Because A2A blockade was ineffective in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice and NK cells (deficient in these mice) are known to be suppressed through A2A activation in vitro (17), we hypothesized that the effects of adenosine in promoting metastasis may be due to suppression of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. To test this, the effect of A2A stimulation on the ability of NK cells to kill B16F10 tumor cells in vitro was determined. The addition of NECA to cocultures of NK cells with B16F10 (Fig. 4A) or 4T1.2 (Fig. S2A) significantly suppressed NK cell-mediated killing activity; this was reversed by the addition of SCH58261, thus supporting a role for A2A-mediated suppression of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Similarly, NECA stimulation inhibited the ability of NK cells to secrete IFN-γ (Fig. 4B) and MIP-1α (Fig. S2B) and reduced their up-regulation of CD69 in response to IL-12 and IL-18 stimulation (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the maturation of NK cells as shown by their up-regulation of CD27 following stimulation with IL-12 and IL-18 was inhibited by NECA (Fig. S2C). Inhibition of NK cell cytokine production, maturation and up-regulation of CD69 by NECA was reversible following A2A blockade but not A2B blockade. Similarly, the effects of NECA were replicated following treatment with the selective A2A agonist CGS-21680. Moreover, NK cells from A2A−/− mice were not modulated by NECA (Fig. 4D). These data indicated that A2A activation potently suppresses NK cell maturation and activation and suggested that A2A blockade may reduce metastasis through enhancement of NK cell function. To explore this further, we evaluated the effect of A2A blockade in perforin-deficient mice, in which NK cell cytolytic activity is impaired. In this setting, SCH58261 treatment was unable to reduce the metastasis of CD73+ B16F10 tumor cells (Fig. 5A) or 4T1.2 tumor cells (Fig. 5B). Although these data indicated that A2A blockade reduced metastasis through enhanced perforin-dependent cytotoxicity, they do not directly implicate NK cells because CD8+ T cells can also kill tumor cells through this mechanism. To confirm that the A2A antagonist SCH58261 was enhancing NK cell activity in vivo, we analyzed the expression of granzyme B from NK cells infiltrating 4T1.2 tumors. Neither A2A nor A2B blockade significantly modulated the frequency of NK cells or CD3+ T cells from within the CD45.2-gated population (Fig. S3); however, a significantly higher proportion of NK cells isolated from mice treated with the A2A antagonist SCH58261 expressed granzyme B compared with those isolated from vehicle or PSB-1115–treated mice (Fig. 5 C and D). These differences were also reflected by an increased mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for granzyme B expression within the NK cells analyzed from SCH58261-treated mice (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these data indicate that the expression of CD73 on tumor cells enhances metastasis through increased A2A-mediated suppression of perforin-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity. Because A2B blockade has previously been shown to modulate the differentiation of MDSCs and the function of macrophages and dendritic cells (18–20), we investigated the impact of A2B blockade on these immune subsets in the metastatic setting. A2B blockade did not modulate the frequency of CD11b+Gr-1hi (MDSCs) in the lungs of 4T1.2 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. S4A). Similarly, the proportion of CD11b+F480+ (macrophages) and CD11bloCD11c+ (dendritic cells) subsets was unaltered in mice treated with the A2B antagonist PSB-1115. Moreover, although A2B activation has been shown to affect dendritic cell maturation in vitro (21), we found no differences in the expression of MHCII and CD86 on the pulmonary CD11bloCD11c+ subset (Fig. S4B). The expression of these markers was also unaltered in the CD11b+F480+ macrophage cells (Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4.

A2A blockade enhances NK cell activity in vitro and perforin-mediated cytotoxicity in vivo. Splenic NK cells were isolated from WT (A–D) or A2A−/− (D) mice. (A) NK cells were cultured in IL-2 (100 U/mL) and after 5 d, washed and then cocultured with 1 × 104 51Cr-labeled B16F10 tumor cells in the presence of vehicle (control) or NECA (1 μM) ±1 μM SCH58261 at indicated effector:target ratios. After 4 h coculture, supernatants were taken and the percentage chromium release determined. Results shown are the mean ± SEM pooled from three individual experiments. NK cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were stimulated with IL-18 (50 ng/mL) and indicated doses of IL-12 in the presence or absence of NECA (1 μM), SCH58261 (1 μM), PSB-1115 (1 μM), or CGS-21680 (100 nM). After 18 h, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for their concentration of IFN-γ (B). The expression of CD69 was determined by flow cytometry (C). (D) NK cells (1 × 104) cells per well were stimulated with IL-18 (50 ng/mL) and IL-12 (100 pg/mL). (B–D) The results shown are the mean ± SD of a representative experiment of n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

Antimetastatic activity of A2A blockade is due to enhanced NK cell function in vivo. (A) WT or perforin−/− mice were treated with SCH58261 (1 mg/kg) or vehicle control at days 0 (−1 h), 1, and 7 and injected i.v. with 2 × 105 B16F10-CD73 tumor cells. Results shown are the mean ± SD of a representative experiment of n = 3. 4T1.2 tumor cells were injected into the fourth mammary fat pad of perforin−/− (B) or WT (C–E) mice at a dose of 5 × 104. Mice were treated with either vehicle control or SCH58261 (1 mg/kg) three times per week with therapy initiated on day 3. (B) After 26 d, lungs were harvested and sectioned. Results shown are the mean ± SEM of 12 mice pooled from two individual experiments (C–E). At day 30, tumors were harvested and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Representative FACS plot showing granzyme B expression within the CD45+CD3−DX5+ (NK cell) subset. (D) Proportion of NK cells expressing granzyme B. (E) MFI of granzyme B within NK cells. (D and E) Data shown are the average MFI. Mean ± SD of five mice of a representative experiment of n = 3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CD73 Can Promote Metastasis Independently of Adaptive Immunity.

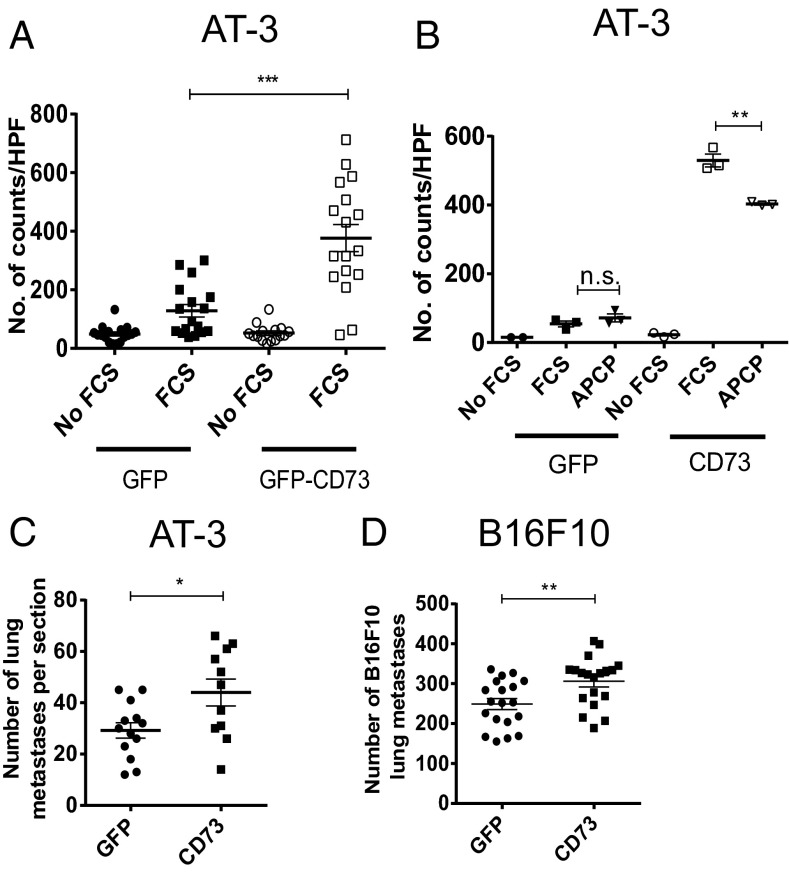

Although our data show a clear role for the CD73:A2A axis in the suppression of NK cells and therefore the increased metastasis of tumor cells, we hypothesized that CD73 may also promote tumor metastasis through other mechanisms. It has previously been observed that CD73 can increase the in vitro migration of tumor lines (7, 22, 23) and their adherence to extracellular matrix proteins (23, 24). Indeed our own data suggest that A2B blockade can reduce the metastasis of CD73+ tumors independently of effects on NK cells (Fig. 2E). To investigate this further, we determined the effect of CD73 expression on the in vitro migration of AT-3 tumor cells. CD73 expression on AT-3 cells significantly enhanced their migration in the Boyden chamber assay compared with GFP control-transduced AT-3 cells (Figs. 6A and S5). The enhanced migration of AT-3 CD73+ tumor cells was significantly reduced by the addition of adenosine 5′-(α,β-methylene)diphosphate (APCP), a specific inhibitor of CD73 enzymatic activity (Fig. 6B). To investigate if CD73+ tumor cells had increased migratory potential in vivo, we investigated whether CD73 could promote the metastasis of tumors in immunocompromised mice. Indeed, expression of CD73 in both AT-3 and B16F10 tumor cells significantly enhanced metastasis in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice, although the effects were less marked than in WT mice (Fig. 6 C and D; compare with Fig. 1 D and E). Although CD73 promoted metastasis in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice, the fold increase in metastasis relative to GFP controls was significantly less than the fold increase in WT mice. Taken together, these data indicate that CD73 enhances metastasis through both immune-dependent and immune-independent pathways.

Fig. 6.

CD73 also enhances metastasis through a nonimmune dependent mechanism. (A and B) AT-3-GFP/AT-3-CD73 tumor cells were seeded at 2 × 105 on the top well of a Boyden chamber containing either serum-free media or FCS-containing media (5%) in the lower compartment. After 4 h, the lower chamber was analyzed by DAPI staining of cell inserts. The average number of cells viewed through a 10× objective was calculated over four fields of view. (A) Mean ± SEM of pooled data from five experiments. (B) Cells were treated with APCP (40 μM) and the effect on migration determined. Mean ± SD for a representative experiment of n = 3 is shown. (C) A total of 1 × 104 AT-3-GFP/AT-3-CD73 or (D) B16F10 GFP/B16F10-CD73 tumor cells were injected i.v. into RAG−/−cγ−/− mice. Lungs were analyzed for metastases 14 d after tumor inoculation. (C and D) Data shown are the mean ± SEM of pooled data from three individual experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

The generation of adenosine by CD73 is an immunosuppressive mechanism that promotes primary tumor growth because of A2A receptor-mediated suppression of antitumor T-cell responses (7, 8, 10–12). CD73 also promotes metastasis, although the mechanisms underlying this have, to date, been largely unknown. In the current study, we have shown that expression of CD73 on tumor cells is sufficient to enhance tumor metastasis. Treatment of mice with selective A2A (SCH58261) or A2B (PSB-1115) antagonists reduced tumor metastasis, suggesting a role for both the A2A and A2B receptors in enhancing CD73+ tumor cell metastasis. We confirmed that the effects of SCH58261 were attributable to the A2A receptor with gene-targeted mice. Although PSB-1115 has been reported to have >200-fold selectivity for the A2B receptor (25) and we observed no activity of PSB-1115 in modulating the function of NK cells in vitro, an A2A-dependent process, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that PSB-1115 reduces tumor metastasis through binding to A2A receptors in vivo. Further experiments in A2B−/− mice or using A2B shRNA knockdown on tumor cells would help address whether PSB-1115 mediates its effects specifically through host or tumor A2B receptors.

Having found that the protective effect of A2A blockade was dependent on host expression of A2A receptors, we consequently found that the activation of A2A receptors was associated with reduced activation, maturation, and cytokine production of NK cells in vitro. Moreover, A2A blockade was ineffective in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice or perforin-deficient mice in which NK cells are absent or their cytolytic function is impaired. Although these results could potentially be explained through the modulation of other perforin-expressing immune subsets such as cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, it has previously been shown that CD8+ or CD4+ T-cell depletion has little effect on the metastasis of B16F10 cells (26); as a result, these results strongly imply a role for NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nevertheless, to demonstrate this directly, we isolated NK cells from tumor-bearing mice and detected significantly enhanced granzyme B expression in NK cells isolated from A2A antagonist-treated mice. This is consistent with other in vitro studies demonstrating diminished NK cell cytotoxicity following A2A stimulation (17, 27). Taken together, our data indicate that suppression of NK cell function is an important mechanism governing the metastasis of CD73+ tumors in vivo. Notably, the activation of A3 receptors has been shown to enhance NK cell activity in vitro and in vivo (28, 29). Thus, A2A blockade may enhance NK cell activity both directly by blocking an immunosuppressive receptor and indirectly by increasing the availability of adenosine for the activating A3 receptor.

Although suppression of NK cell activity is clearly an important mechanism governing the metastasis of CD73+ tumors, we observed that in contrast to A2A blockade, A2B blockade did not modulate the activation or cytokine production of NK cells. This indicates a distinct mechanism governing the antimetastatic effect of A2B antagonism. A2B activation is known to modulate several subsets of myeloid cells, including dendritic cells (21, 30–32), macrophages (19, 33, 34) and MDSCs (20). Notably, in the context of the primary tumor site, it has been reported that A2B blockade could enhance the expression of CD86 on CD11b− dendritic cells and consequently induce more potent antitumor immune responses (18). Similarly, the activation of the A2B receptor has been shown to enhance the expansion of MDSCs in s.c. tumors (20). However, we did not find any evidence of modulation of these subsets in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice, suggesting this is not the mechanism by which A2B activation promotes tumor metastasis. Our results are consistent with recent work by another group suggesting that A2B stimulation may enhance metastasis through an immune-independent mechanism (35). Knockdown of A2B on tumor cells was reported to reduce the lung metastasis of breast cancer tumor cells by being associated with impaired formation of filopodia and reduced in vitro migratory and invasiveness (35). This supports our previous observation that A2B stimulation with a pharmacological agonist could enhance tumor cell migration in vitro (7). Furthermore, the production of adenosine by CD73 was recently shown to enhance the adhesion of tumor cells to the extracellular matrix (36). In the current study, we found that both NECA and CD73 enhanced the metastasis of B16F10 tumor cells in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice, albeit that the increase in metastasis was less pronounced than in WT mice. Increased metastasis in these immunocompromised mice was reversed by A2B blockade, supporting the conclusion that the CD73-A2B axis promotes metastasis through an immune-independent pathway. In our study, we demonstrated that ectopic expression of CD73 promoted the in vitro migration of AT-3 tumor cells. This is in agreement with a previous report using human breast cancer cell lines (22) and with our own study using CD73 knockdown on 4T1.2 tumor cells. The migration of CD73+ tumor cells was significantly reduced by APCP, implying a role for CD73-generated adenosine in tumor metastasis. Notably, however, the inhibition mediated by APCP was only partial despite the fact that we demonstrated that APCP was capable of almost completely abrogating the conversion of AMP into adenosine by CD73 at this concentration (Fig. S1). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that CD73 enhances migration and, as a consequence, metastasis through an adenosine independent pathway. Indeed, CD73 was previously identified as lymphocyte-vascular adhesion protein 2, and implicated in the binding of lymphocytes to endothelial and dendritic cells (37–39). In these studies, engagement of CD73 was found to trigger LFA-1 clustering and hence promote cell–cell interactions. Although the requirement for adenosine production by CD73 was not investigated in these studies, it has been shown that the enzymatic activity of CD73 was not required for its T-cell stimulatory function (40). Thus, in future studies, it would be interesting to generate tumor cells expressing a kinase dead variant of CD73 to determine the potential impact on metastasis of CD73 in the absence of enhanced adenosine production.

In summary, we have identified a mechanism by which CD73 enhances the metastasis of tumors in vivo, involving the activation of A2A receptors on NK cells and subsequent reduction in NK cell function. Our data have significant therapeutic potential in the treatment of tumor metastasis given that (i) CD73 expression was shown to be a predictor of metastasis in breast cancer patients (13) and (ii) there are adenosine receptor antagonists already in clinical trials for other disease settings. The A2A antagonists istradefylline (KW-6002; phase III) (41), preladenant (SCH-420814; phase II) (42), and SYN-115 (phase IIb) (16, 43) have completed clinical trials for Parkinson disease, whereas the A2B antagonist CVT-6883 has undergone a phase I trial (25). All three compounds were safe and well-tolerated, indicating that a pathway to the clinic for drugs of this class maybe relatively straightforward. Because a link has been shown between CD73 expression and metastasis in breast cancer patients (13), further investigation into the therapeutic potential of A2A/A2B blockade is warranted.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Mice.

The C57BL/6 mouse breast carcinoma cell line AT-3 was obtained from Trina Stewart (Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia) (44), 4T1.2 tumor cells were kindly provided by Robin Anderson (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia), and the C57BL/6 melanoma line B16F10 was obtained from ATCC. AT-3 and B16F10 cells were grown in DMEM and 4T1.2 cells in RPMI. Both DMEM and RPMI were supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, glutamax, and penicillin/streptomycin. For in vivo experiments, the indicated number of cells were resuspended in PBS and injected s.c. (100 μL), i.v. (200 μL), or into the fourth mammary fat pad (20 μL). C57BL/6 and BALB/c WT mice were obtained from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia) and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Melbourne, Australia), whereas RAG−/−cγ−/− and perforin−/− mice were bred in house at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. Because the metastatic potential of tumor cells was dramatically increased in RAG−/−cγ−/− mice, the number of cells injected into these mice was reduced as indicated. A2A−/− mice were bred at St. Vincent’s Hospital. All animal experimentation was approved in advance by the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee.

Vectors and Tumor Cell Transduction.

Murine CD73 cDNA (Open Biosystems) was cloned into the plasmid murine stem cell vector (pMSCV)-GFP retroviral vector. Retroviruses were made by transfection of either pMSCV-GFP or pMSCV-GFP-CD73 in combination with the pMD2.G envelope vector into HEK293gagpol cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. For ectopic CD73 expression, AT-3 and B16F10 tumor cells were transduced with retroviral supernatants in the presence of polybrene (4 μg/mL) and “spinfection” at 700 × g for 90 min. After four rounds of transduction, the cells were sorted based upon the expression of GFP.

Antibodies, Agonists, and Antagonists.

NECA, CGS-21680, SCH58261, PSB-1115, and APCP were purchased from Sigma. BAY-60-6583 was gifted by Bayer. TY/23 (anti-CD73 mAb) antibody was produced in house from hybridoma cells provided by Linda Thompson (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK).

Chemotaxis Assay.

The migration of AT-3-GFP and AT-3-CD73 tumor cells was determined in a Boyden chamber assay as previously described (7).

Quantification of Metastatic Burden.

B16F10 macrometastases on the surface of the lungs were counted using a dissecting microscope (Olympus SXZ7). Metastasis of 4T1.2 and AT-3 cells were determined in sections of the lung stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The number of metastases per section was counted.

NK Cell Cytotoxicity Assay.

Splenic NK cells were isolated from WT C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice using the NK cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) and were cultured for 5 d in NK cell media (RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, nonessential amino acids, Pyruvate, Hepes, glutamax, 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin/streptomycin) and 1,000 U/mL of IL-2. B16F10 cells, labeled with 100 μCi/1 × 106 cells of 51Cr, were cocultured with the indicated ratio of IL-2–blasted NK cells.

NK Cell in Vitro Stimulation.

Splenic NK cells were isolated from age-matched WT or A2A−/− C57/BL6 mice using the NK cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) or FACS isolated based upon a gate of CD3−, NK1.1+ and plated into a 96-well plate. NK cells were cultured in NK cell media and preincubated with or without 1 µM SCH58261 30 min before simulation with indicated concentrations of IL-18 (R & D Systems) and IL-12p70 (Australian Biosearch) in the presence or absence of NECA (1 µM) or CGS-21680 (100 nM).

Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Subsets.

After killing the mice, tumors were excised and digested using a mix of 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.02 mg/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich). After 45 min digestion at 37 °C, cells were twice passed through a 70-μm filter. Single-cell suspensions were then analyzed by flow cytometry with 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) used to discriminate viable and dead cells. To block nonspecific binding through Fc receptors, 2.4G2 was used and incubated with the cells for 30 min at 4 °C. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the ebioscience fixation/permeabilization kit as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney test, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Experimental Animal facility technicians for animal care, the Histology Department (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre) for the processing of hematoxylin and eosin sections of lung tissue, and Dr. Delphine Denoyer for her assistance with TLC analysis. The authors also acknowledge Bayer for provision of the A2B agonist BAY60-6583. This work was funded by project grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Susan G. Komen for the Cure, an American Department of Defense Breast Cancer Fellowship (to C.P.), an NHMRC Australian Research Fellowship (to M.J.S. and P.A.B.), an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (to P.K.D.), and a Famille Sabourin Research Chair of University of Montreal and Operating Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to J.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.A.R. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1308209110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Koebel CM, et al. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature. 2007;450(7171):903–907. doi: 10.1038/nature06309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohta A, et al. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(35):13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohta A, et al. A2A adenosine receptor may allow expansion of T cells lacking effector functions in extracellular adenosine-rich microenvironments. J Immunol. 2009;183(9):5487–5493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beavis PA, Stagg J, Darcy PK, Smyth MJ. CD73: A potent suppressor of antitumor immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(5):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loi S, et al. CD73 promotes anthracycline resistance and poor prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(27):11091–11096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222251110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stagg J, et al. Anti-CD73 antibody therapy inhibits breast tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(4):1547–1552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stagg J, et al. CD73-deficient mice have increased antitumor immunity and are resistant to experimental metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(8):2892–2900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stagg J, et al. CD73-deficient mice are resistant to carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2190–2196. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yegutkin GG, et al. Altered purinergic signaling in CD73-deficient mice inhibits tumor progression. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(5):1231–1241. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, et al. CD73 has distinct roles in nonhematopoietic and hematopoietic cells to promote tumor growth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2371–2382. doi: 10.1172/JCI45559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin D, et al. CD73 on tumor cells impairs antitumor T-cell responses: A novel mechanism of tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Res. 2010;70(6):2245–2255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leth-Larsen R, et al. Metastasis-related plasma membrane proteins of human breast cancer cells identified by comparative quantitative mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(6):1436–1449. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800061-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Lin EC, Liu L, Smith JW. Gene expression profiling of tumor xenografts: In vivo analysis of organ-specific metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(4):528–534. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B. CD73: A novel target for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70(16):6407–6411. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JF, Eltzschig HK, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets—what are the challenges? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(4):265–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoskin DW, Mader JS, Furlong SJ, Conrad DM, Blay J. Inhibition of T cell and natural killer cell function by adenosine and its contribution to immune evasion by tumor cells (review) Int J Oncol. 2008;32(3):527–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cekic C, et al. Adenosine A2B receptor blockade slows growth of bladder and breast tumors. J Immunol. 2012;188(1):198–205. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csóka B, et al. Adenosine promotes alternative macrophage activation via A2A and A2B receptors. FASEB J. 2012;26(1):376–386. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-190934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryzhov S, et al. Adenosinergic regulation of the expansion and immunosuppressive activity of CD11b+Gr1+ cells. J Immunol. 2011;187(11):6120–6129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson JM, et al. The A2B adenosine receptor impairs the maturation and immunogenicity of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):4616–4623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase promotes invasion, migration and adhesion of human breast cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(3):365–372. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0292-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadej R, Spychala J, Skladanowski AC. Expression of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (eN, CD73) in cell lines from various stages of human melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2006;16(3):213–222. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000215030.69823.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieckhoff J, et al. The extracellular matrix proteins laminin and fibronectin modify the AMPase activity of 5′-nucleotidase from chicken gizzard smooth muscle. FEBS Lett. 1986;195(1-2):82–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalla RV, Zablocki J. Progress in the discovery of selective, high affinity A(2B) adenosine receptor antagonists as clinical candidates. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5(1):21–29. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow MT, Tschopp J, Möller A, Smyth MJ. NLRP3 promotes inflammation-induced skin cancer but is dispensable for asbestos-induced mesothelioma. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90(10):983–986. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Häusler SF, et al. Ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 on OvCA cells are potent adenosine-generating enzymes responsible for adenosine receptor 2A-dependent suppression of T cell function and NK cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(10):1405–1418. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harish A, Hohana G, Fishman P, Arnon O, Bar-Yehuda S. A3 adenosine receptor agonist potentiates natural killer cell activity. Int J Oncol. 2003;23(4):1245–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morello S, et al. NK1.1 cells and CD8 T cells mediate the antitumor activity of Cl-IB-MECA in a mouse melanoma model. Neoplasia. 2011;13(4):365–373. doi: 10.1593/neo.101628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson JM, et al. The A2B adenosine receptor promotes Th17 differentiation via stimulation of dendritic cell IL-6. J Immunol. 2011;186(12):6746–6752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panther E, et al. Adenosine affects expression of membrane molecules, cytokine and chemokine release, and the T-cell stimulatory capacity of human dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;101(10):3985–3990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novitskiy SV, et al. Adenosine receptors in regulation of dendritic cell differentiation and function. Blood. 2008;112(5):1822–1831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-136325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryzhov S, et al. Effect of A2B adenosine receptor gene ablation on adenosine-dependent regulation of proinflammatory cytokines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(2):694–700. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreckler LM, Wan TC, Ge ZD, Auchampach JA. Adenosine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha release from mouse peritoneal macrophages via A2A and A2B but not the A3 adenosine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(1):172–180. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desmet CJ, et al. Identification of a pharmacologically tractable Fra-1/ADORA2B axis promoting breast cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(13):5139–5144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222085110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappellari AR, Vasques GJ, Bavaresco L, Braganhol E, Battastini AM. Involvement of ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 in U138MG glioma cell adhesion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;359(1-2):315–322. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Airas L, et al. CD73 is involved in lymphocyte binding to the endothelium: Characterization of lymphocyte-vascular adhesion protein 2 identifies it as CD73. J Exp Med. 1995;182(5):1603–1608. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Airas L, Jalkanen S. CD73 mediates adhesion of B cells to follicular dendritic cells. Blood. 1996;88(5):1755–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Airas L, Niemelä J, Jalkanen S. CD73 engagement promotes lymphocyte binding to endothelial cells via a lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;165(10):5411–5417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutensohn W, Resta R, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Thompson LF. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity is not required for T cell activation through CD73. Cell Immunol. 1995;161(2):213–217. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park A, Stacy M. Istradefylline for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(1):111–114. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.643869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Factor SA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of preladenant in subjects with fluctuating Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28(6):817–820. doi: 10.1002/mds.25395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Black KJ, Koller JM, Campbell MC, Gusnard DA, Bandak SI. Quantification of indirect pathway inhibition by the adenosine A2a antagonist SYN115 in Parkinson disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30(48):16284–16292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2590-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stewart TJ, Abrams SI. Altered immune function during long-term host-tumor interactions can be modulated to retard autochthonous neoplastic growth. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):2851–2859. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.