Abstract

This study examines the role that parenting and deviant peers plays on frequency of self-reported violent behavior in the 10th grade, while testing race differences in mean levels and impact of these risk and protective factors. The level and impact of family and peer factors on violent behavior across race are modeled prospectively from 8th to 10th grade in a sample of 331 (nBlack = 162, nWhite = 168) families from Seattle, WA using data from self-administered computer-assisted questionnaires. Mean-level differences indicated greater levels of violent behavior and risk for Black teens in some cases and higher protection in others. Multiple-group structural equation modeling indicated no race differences in predictors of teen violence. Income was also predictive of violent behavior but analyses including both income and race indicated their relationships to violence overlapped so neither was uniquely predictive. Subsequent logistic regressions revealed that both race and income differences in violent behavior were mediated by association with friends who get in serious trouble at school. We conclude higher rates of self-reported violent behavior by Blacks compared to Whites are attributable to lower family income and higher rates of associating with deviant peers at school.

Keywords: race, deviance, monitoring, attachment, aggression

Introduction

In 2008, national crime arrest statistics indicated that youth under age 18 in the United States were responsible for 16.2% of all violent crime arrests defined as murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2008). Self-reports of youth violence reveal many more offenses compared to official crime statistics. For instance, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009), 36% of high school students reported being in a physical fight one or more times in the year preceding the survey, and 18% reported carrying a weapon on one or more of the 30 days preceding the survey. Racial disparities in violence are well documented. According to the 2008 FBI crime data, Black juveniles are 5 times more likely to be arrested for violent crime than are White juveniles (Puzzanchera, 2009). However, such data relies solely upon arrest records, which may be influenced by other variables such as income, neighborhood cohesion and environment, and law enforcement practices (Crutchfield, Skinner, Haggerty, McGlynn, & Catalano, 2009; Huizinga et al., 2007). Therefore, studies have also focused on using self-report data to explore disparity in violent offending. While juvenile self-report data tends to show less racial disparity in violence perpetration than official arrest data, differences in frequency of violent offending between Blacks and Whites persist (Crutchfield et al., 2009).

Based on a contextual perspective, we consider violence to be a product of individual characteristics and risky and protective social contexts. Many researchers have emphasized that youth violence is complex problem behavior determined by dynamic interplay of individual and key social influences on adolescents, such as family, peer, school, and community (Farrell & Flannery, 2006; Hawkins et al., 1998; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Huang, Kosterman, Catalano, Hawkins, & Abbott, 2001; Kosterman, Graham, Hawkins, Catalano, & Herrenkohl, 2001; Resnick, Ireland, & Borowsky, 2004). From an ecological framework, the more proximal context of family should be more salient than distal contexts such as school or neighborhood (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The social development model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996) emphasizes the importance of position in the social structure as well as parent influences on opportunity structures including schools, neighborhoods, and peer selection. The link between parenting practices and peer selection is particularly important as teens gain more independence and freedom. Parenting practices such as setting clear guidelines and expectations for behavior, being clear and consistent in enforcing appropriate consequences for infractions, and monitoring or staying abreast of the teen's whereabouts are especially important as they can influence opportunities for involvement with deviant peers. This study examines the link between skilled parenting practices and negative peer influences as they relate to the violent behavior of teens. .

Income and Violence

Much of the existing research on racial disparities in violence has pointed to economic variables that help partially explain Black-White differences in adolescent violence perpetration. Research suggests that higher income is associated with fewer violent behaviors among both Black and White adolescents (Blum et al., 2000; Hsieh & Pugh, 1993). However, Black adolescents are more likely to come from families with fewer economic resources and live in communities characterized by higher levels of disadvantage than their White counterparts (Jargowsky, 1996; Massey, 1990). Many other studies have also found that different levels across race of other measures of disadvantage (community disadvantage and cumulative disadvantage) can contribute to an explanation of the variation in racial disparity in violence (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2006; Haynie, Silver, & Teasdale, 2006; McNulty & Bellair, 2003).

Families and Violence

Racial disparities in violent behavior may be the effect of Black families having fewer economic resources. Parents who lack adequate financial resources often find themselves with less time to engage in closely monitoring their children (Conger et al., 1992), and may use more power-assertive forms of discipline (Heimer, 1997), both of which have been shown to increase the probability that a child will associate with deviant peers and become involved in violent or delinquent behaviors. Researchers argue that while economic factors can help explain some of the differences between Blacks and Whites in violent offending, they often do not explain all of the disparity (Blum et al., 2000; Haynie et al., 2006).

Researchers have identified many ways in which parenting practices impact problem behavior such as delinquency and violence (Hawkins et al., 1998; Henry, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984; Windle et al., 2010). Many researchers have argued that negative parenting practices, including harsh or inconsistent discipline, directly influence the development of violent or delinquent behaviors (Hawkins et al., 1998; Henry et al., 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984). Both overly harsh and lax discipline have been linked to a range of adolescent problem behaviors, including violence (Farrington, 1989; Hawkins et al., 1992). Researchers have often found that adolescents who have been exposed to harsh and violent forms of discipline are more likely to become violent as adolescents and young adults (Heimer, 1997). Additionally, parental history of violence has been associated with the violent behavior of children (Hawkins et al., 1992; Herrenkohl et al., 2000).

Caregivers can also have a protective influence on their children. Research has found that positive parenting practices that include establishing clear guidelines for behavior, positive monitoring, and the delivery of fair and consistent consequences can act as a buffer, shielding an adolescent from involvement in violent or delinquent behavior (Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004; Griffin, Botvin, Scheier, Diaz, & Miller, 2000; Henry et al., 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2003). Recent research finds that families play an important role in establishing guidelines for behaviors, in monitoring behaviors, and providing both positive and negative consequences for behaviors across races (Windle et al., 2010).

Bonding or attachment to a primary caregiver is also an important family protective factor (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). This argument is consistent with Hirschi's (1969) control theory—children do not want to damage the bonds with parents and therefore avoid situations which would vary from parental expectation for child behavior. Mack and colleagues (2007), in support of Hirschi's control theory, found that maternal attachment was a stronger predictor of youth delinquency than family structure or economic variables. Adolescents with greater attachment were less likely to engage in serious delinquency, including violent behavior.

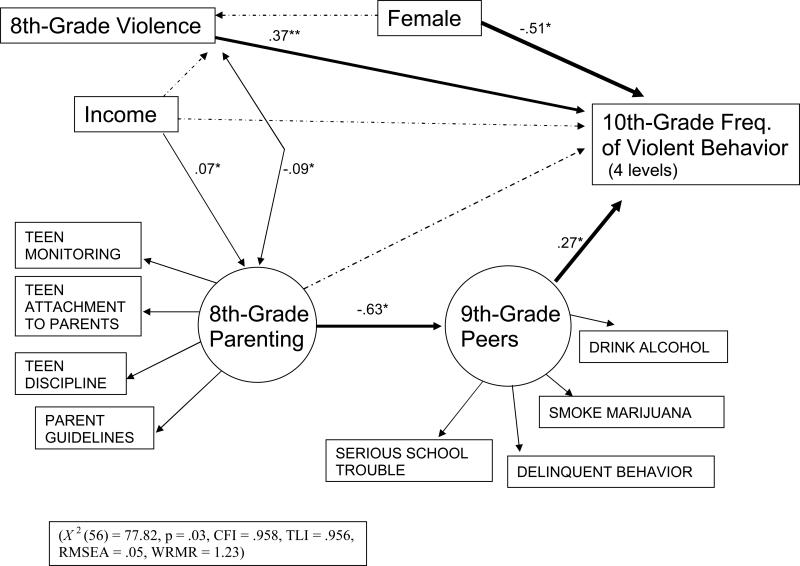

Monitoring of adolescent behavior and friendships has consistently been linked with reduced levels of delinquency (Griffin et al., 2000; Laird, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2008; Larzelere & Patterson, 1990; Warr, 2005), and to some extent, violence (Windle et al., 2010). Research suggests that parental monitoring may mediate the relationship between attachment and peer formation (Ingram, Patchin, Huebner, McCluskey, & Bynum, 2007; Warr, 2005). Children with strong attachments to parents may be more likely to open themselves up to being monitored (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). They may be more likely to disclose to their parents who they will be with and where they are going.Some researchers have argued that parental supervision directly impacts deviant behavior. Children who are aware that they are being monitored are less likely to engage in deviant behavior (Griffin et al., 2000), while children who are not consistently monitored are more likely to engage in delinquent behavior (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). However, other studies of parental monitoring have suggested that the relationship between parental supervision and delinquent outcomes may be mediated by peer affiliations (Ingram et al., 2007; Laird et al., 2008; Warr, 2005). Warr (2005) finds that parental supervision affects the type of friends that adolescents acquire (see Figure 1). Parents who provide monitoring are less likely to have children who associate with deviant peers. However, this evidence for mediation has been provided primarily in White samples (Forgatch & Stoolmiller, 1994; Oxford, Harachi, Catalano, & Abbott, 2001; Patterson & Dishion, 1985). Further, more research has focused on the mediating role of parenting on peer selection and adolescent delinquency, while less research has focused on examining this relationship for youth violent behavior.

Figure 1.

Parenting and peer influences on violent behavior from 8th to 10th grade.

Peer Affiliation and Violence

Perhaps one of the most salient factors related to violent behavior is the influence of antisocial peers (Hawkins et al., 1992; Herrenkohl et al., 2003). In adolescence, young people begin to establish self-identify and autonomy while starting to distance themselves from parental authority (Muuss, 1996). During this stage of life, peer influences on adolescent thought and behavior increase. Youth commonly adopt peer group norms, values, and behavior, and seek peer support and acceptance. Many studies demonstrate that exposure to negative peers is the most important risk factor for antisocial behavior, including violence (Hawkins et al., 1998; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). If Black youth are exposed to more negative peer influences, then negative peers may mediate the relationship between race and violent behavior (Haynie & Payne, 2006). While the role of prosocial peers has been less studied there is some evidence that strong bonds with prosocial peers can buffer or mitigate the impact of negative peer influences on problem behaviors, including violent behavior (Kaufmann, Wyman, Forbes-Jones, & Barry, 2007; Kobus, 2003).

This study examines the relationships between positive parenting practices and deviant peers and the frequency of self-reported violent behavior in the 10th grade. We also examine race differences in mean levels and the impact of these risk and protective factors on self-reported violent behavior. The level and impact of family and peer factors on violent behavior across race are modeled prospectively from 8th to 10th grade in a sample of 331 (nBlack = 162, nWhite = 168) families from Seattle, WA using data from self-administered computer-assisted questionnaires. Understanding possible race differences in the role of parent and peer risk and protective factors will lead to improvements in targeted preventive efforts in family and school-based programs. Mean-level differences in risk factors can be addressed universally. However, if the risk and protective factors which influence violence are different in each group, preventive efforts must ensure that the appropriate factors are targeted by preventive efforts.

Methods

The current study draws on data from a longitudinal study of 331 families, half who are White, and half who are Black, also balanced by gender. The longitudinal study includes an experimental trial of the impact of Parents Who Care, a preventive intervention to reduce problem behaviors. Previously published reports on the effects of the intervention found reduced frequency of violent behavior for Black, but not White teens (Haggerty, Skinner, MacKenzie, & Catalano, 2007). To control for possible intervention differences in the impact of parent and peer predictors of violence, intervention group was included as a dummy variable in the multiple-group structural equation model (MGSEM). These dummy variables were not significant in these models, and MGSEM by race found no significant differences by race in the impact of intervention group on the outcome or the mediating effects of associating with deviant peers, or on the magnitude of relationships in the models tested.

Study Sample, Design, and Setting

Parents of eighth-grade students in Seattle Public Schools received a letter describing the study, and the parents were contacted by phone. Families were included if the teen and one or both parents consented to participate. Eligibility included self-identifying as Black or White, speaking English as their primary language, and planning to live in the area for at least 6 months. Forty-six percent consented (55% of Blacks and 40% of Whites). The parents who refused were more likely to be White, married, and had a higher education on average than those who consented. Three hundred and thirty-one (nBlack = 162, nWhite = 168) families consented to participate. All protocols were approved by the University of Washington (Seattle, WA) internal review board.

The sample was stratified by teen race and gender to meet the requirements of the original randomized trial of Parents Who Care. Sufficient numbers from each group were necessary to test for race differences in the efficacy of the intervention. Families were recruited based on parental report of teen race to the school district (African American or European American) and gender (male or female) into a design with roughly equal numbers in each of the four cells. Recruitment of new families stopped when all four cells were full.

There were significant differences by race on several demographic variables. Whites reported higher per capita income and parental education, and Blacks reported higher prevalence of single parenthood (Table 1). Some teens in each race group self-identified as mixed race (19.6% Black; 12.5% White), but were included in these analyses because the study design was based on parental report to the school district and because teen self-reported race changed somewhat over time making categorization more difficult. Most primary caregivers were female (> 80%), with 71.6% being the adolescent's biological mother. Gender and relationship of caregiver were similar across race with one exception: more Black youth had another female caregiver (e.g., grandmother, aunt) as a primary caregiver than did White youth [X2 (1) = 13.95, p < .001].

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Race

| Variable | Black (S.D.) | White (S.D.) | Total (S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eighth grade | |||

| % male | 50.9 | 51.8 | 51.4 |

| Mean age of child | 13.7 yrs (.48) | 13.7 yrs (.40) | 13.7 yrs (.44) |

| % single parent | 57% | 24%** | 40% |

| Parent college graduate | 13% | 61%** | 38% |

| Mean per capita income | $7807 (9,390) | $21,970** (15,958) | $15,042 (14,932) |

| Frequency of violent behavior (by category) | |||

| 0 = none | 74.8% | 80.9% | 77.9% |

| 1 = 1 to 2 times | 11.6% | 11.9% | 11.7% |

| 2 = 3 to 5 times | 8.6%* | 2.9% | 5.7% |

| 3 = 6 or more times | 4.9% | 4.1% | 4.5% |

| Guidelines | 3.3 (.75)** | 3.0 (.67) | 3.1 (.72) |

| Attachment | 101.8 (19.48) | 104.1 (21.62) | 102.9 (20.57) |

| Monitoring | 3.5 (.48) | 3.5 (.44) | 3.5 (.46) |

| Discipline | 3.4 (.79) | 3.3 (.75) | 3.4 (.77) |

| Ninth-grade deviant peers | |||

| Serious school trouble | 31.6%* | 21.5% | 26.4% |

| Delinquent behavior | 26.9% | 23.5% | 23.5% |

| Smoking marijuana | 33.1% | 32.7% | 32.7% |

| Drinking alcohol | 42.8% | 51.6% | 47.1% |

| Tenth grade | |||

| Frequency of violent behavior | |||

| 0 = none | 73.5% | 84.2% | 78.9% |

| 1 = 1 to 2 times | 11.3% | 7.9% | 9.6% |

| 2 = 3 to 5 times | 6.6% | 5.9% | 6.3% |

| 3 = 6 or more times | 8.6%* | 2.0% | 5.3% |

significant race difference p < .05

p < .001.

Data collectors went to the families’ homes. Questionnaires were self-administered to teens and their parents in their homes using laptop computers while the data collector was present. Efforts were made to have the questionnaires completed privately and parents did not monitor their teens’ responses. Identical questionnaires were collected when the teens were in the 8th, 9th, and 10th grades. Family members received $15 each time they completed a questionnaire.

Attrition analyses

At posttest, 94.7% of the sample participated in the survey (Black 93.2%, White 95.2%). During the 1-year follow-up, 92.5% of families were interviewed (Black 92%, White 92.9%). Two-year follow-up yielded 92% of the sample, with no completion differences by race. Both parent and teen interviews were completed for 303 families. There were no significant differences between attriters and nonattriters on any of the variables included in these analyses.

Measures

Data on demographics and parenting were collected in the eighth grade. Parents reported their child's race on school enrollment forms. Household per capita income was calculated from parent's endorsement of 1 of 11 categories of annual household income (before taxes). We assigned the midpoint of the range and then divided by the number of people in the household. To reduce the effects of outliers we used a log transformation.

Parental guidelines (rules and consequences for substance use) were assessed with six items (alpha = .79) on a 4-point scale measuring parental agreement with statements such as “I have clear and specific rules about my teen's use of tobacco, alcohol, and illegal drugs.”

Monitoring was assessed with the mean of teen responses to seven items (alpha = .77) on a 4-point scale measuring their agreement, for example, of whether the teen believes his/her parent knows who his/her friends are, where the teen is, and what he/she is doing. This measure reflect the teen's perception of how much knowledge their parent has about where they are and who they are with, not active attempts by parents to obtain that knowledge.

Consequences was measured using the mean of two items (r = .47) on the same 4-point scale: “If you skipped school, would you get caught and punished?” and “If you drank beer or wine without your parent's permission, would you get caught and punished?”

Parent-teen attachment was measured using the sum of 28 items (alpha = .94) from the teen report on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment on a 5-point scale from “never or almost never true” to “always or almost always true” (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Example items include “My parents understand me,” “I trust my parents,” and “My parents sense when I’m getting upset.”

Delinquent behavior and substance use of peers was measured with teen report in ninth grade. The teens were asked to name their three best (or closest) friends (first names or initials only), and were then asked a series of questions about each of those friends: alcohol and marijuana use, getting in serious trouble at school, or having done anything in the last year that could have gotten them in trouble with the police. A dichotomous score was created for each question, with 1 indicating at least one of the friends had engaged in the behavior. Each of the four dichotomous variables was used as an indicator of a latent construct.

Frequency of violent behaviors in the last 30 days was measured identically in the 8th and 10th grades. Items included starting a fight, hitting someone to hurt them, hitting parents (not playing), carrying a gun to school, and throwing rocks at people or cars. Summing across the categorical items produced the following categories: 0 = never, 1 = 1 to 2 times, 2 = 3 to 5 times, 3 = 6 or more times.

Analysis

Simple mean differences in level of risk and protective factors were estimated using t-test or chi-square test. Correlations were run among all of the variables and violence. Tests of the theoretical model which examines a model of parental and peer influences on violent behavior were conducted using structural equation models. These models are particularly suited to tests of somewhat complex models of meditational processes and comparisons between groups. They have the added advantage of improving statistical power and reducing the impact of measurement error by modeling latent constructs based on multiple related measures intended to converge on a true score (see Bentler, 1980). Correlated measures of parental influences (monitoring, discipline, attachment, and guidelines) and deviant peer behaviors (marijuana and alcohol use, delinquent behavior, and trouble at school) were modeled as latent constructs (Jöreskog, 1971). These latent constructs have been used in previous reports from this study (Skinner, Haggerty, & Catalano, 2009) and others (Forgatch, Patterson, Degarmo, & Beldavs, 2009; Herrenkohl, Hill, Hawkins, Chung, & Nagin, 2006) as a measure of skilled parenting. Multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) (Bontempo & Hofer, 2006; Muthén, 1989) was conducted on the two latent constructs: parenting and deviant peers. This step is necessary to confirm that the measures for parenting and deviant peers are comparable for Blacks and Whites, and therefore comparisons in the predictive relationships between constructs are appropriate.

Multigroup structural equation models (MGSEM) by race were used to estimate race moderation of the impact of parental influences in the 8th grade and association with deviant peers in the 9th grade on the frequency of violent behavior in the 10th grade, controlling for previous violent behavior, gender, and family income. Parenting and deviant peers were modeled as latent constructs based on the model described above. Goodness of fit indices are compared between a model in which the predictive relationships are constrained to be equal in both groups (Blacks and Whites in this case) and fit indices when all of the predictive relationships are free to vary between groups. A significant difference in the two fit indices suggests that the ‘free’ model fits the data better than the ‘constrained’ model and therefore there are some significant differences between parameters in the Black compared to the White sample. If the differences between the fit of the two models is not significant we can conclude that the predictive relationships are the same for Blacks and Whites.

A set of ordinal logistic regressions was estimated to test for possible mediation of race differences in violent behavior through the risk factors for which race differences in mean levels were significant. Ordinal logistic regressions are appropriate for testing the effects of multiple factors on an outcome measured in unevenly spaced levels. Our measure of self-reported violent behavior clearly indicates high levels for more frequent violent acts, but is not precise enough to distinguish exact levels.

Results

Group differences in outcomes and predictors are presented in Table 1, arranged by grade. Categorical differences indicated more frequent violent behavior in the 8th and 10th grade among Black than White teens (d = .30). The first question we address is whether there are mean-level differences in risk and protective factors by race. Whites have higher per capita incomes. Black teens experienced stronger family guidelines. Black teens were not more likely to associate with drinking, smoking, or delinquent peers, but were more likely than White teens to associate with peers who experienced serious school trouble. Reports of discipline, monitoring, or attachment to their parents were not different between White and Black teens.

The second question examined whether there are race differences in vulnerability to risk and protective processes. First, we examined bivariate correlations separately for Black and White teens. Low attachment to parents was significantly related to violence for Whites (r = −.21), but not for Blacks (r = −.04). The strongest, and only other significant correlation for both Blacks (r = .22) and Whites (r = .19) to violent behavior is association with peers that have trouble at school. However, a variety of differences emerged between a number of the predictors for Blacks and Whites (e.g., peer trouble at school was significantly positively associated with peer alcohol (r = .37) and marijuana (r = .41) use for Whites but not for Blacks (r = .13 and .14, respectively), suggesting that the relationship between predictors may be meaningfully different for Blacks and Whites. We then conducted a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis to verify equality of measurement in the two latent variables by race and gender. The intercept and loading for guidelines were significantly higher in the Black than in the White sample, and were freely estimated, while all other intercepts and loadings were constrained to be equal across groups (see Table 2). These results suggest an acceptable level of equality of the measures across race. Similar analyses confirmed no differences in measurement parameters by gender.

Table 2.

Intercepts and Loadings for Indicators of Parenting and Peers Latent Constructs

| Indicator | Intercept | Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Eighth-grade parenting | ||

| Guidelines | 3.54/3.311 | .10/1.121 |

| Attachment | .52 | .47 |

| Monitoring | 2.41 | 1.00 |

| Discipline | 2.98 | .82 |

| Ninth-grade deviant peers | ||

| Serious school trouble | .47 | .88 |

| Delinquent behavior | .04 | 1.05 |

| Smoking marijuana | .29 | 1.00 |

| Drinking alcohol | .71 | 1.07 |

White and Black parameter estimates respectively. The loading is significant for Blacks but not Whites.

In light of measurement equality, the structural model represented in Figure 1 was examined for race differences in predictive relationships. Rectangles indicate measured variables. Circles indicate latent variables. Arrows indicate the predictive relationships between variables. Factor loadings and intercepts were estimated simultaneously with causal paths but are provided in Table 2 rather than included in the figure for the sake of clarity and simplicity. The fully constrained model fit the data (X2 (56) = 77.82, p = .03, CFI = .958, TLI = .956, RMSEA = .05, WRMR = 1.23 Δ = X2 (12) = 5.2, p = .95), and the difference between the constrained and unconstrained models was not significant. Thus, the MGSEM indicated no race differences in predictors of teen violence. Unstandardized coefficients indicated that several of the hypothesized relationships were significant across groups. Males were more frequently violent. Income was significantly related to concurrent parenting in 8th grade, but not directly predictive of violent behavior in either 8th or 10th grade. There was a negative association between positive parenting and violent behavior at eighth grade (double headed arrow). Parenting factors significantly reduced associating with deviant peers one year later. Association with deviant peers increased violent behavior one year later. The impact of parenting on violent behavior was mediated through decreased association with deviant peers in both race groups. Prior violent behavior was a significant predictor of 10th-grade violence. The model explained slightly more variance in violence for Whites than for Blacks (r2 = .30 vs. .24).

Finally, a set of ordinal logistic regressions was estimated to test for possible mediation of race differences in violent behavior through the risk factors for which race differences in mean levels were significant (parent education, single parent status, family income, parent report of guidelines, and teen report of friends who get in serious school trouble). Gender and eighth-grade violent behavior were included as control variables in each equation. Parent education, single-parent status, and parent guidelines did not significantly predict violence and therefore did not meet the requirements for mediation, and therefore could not explain race differences in violent behavior. Family income approached significance in predicting violence (b = −.27, p = .058), but when race was included neither race nor income were significant, suggesting that both race and income explain frequency of violent behavior, but the variance they explain is the same, neither contributing uniquely to explain its variability. Having friends who get in serious trouble in school in the 9th grade significantly predicts 10th-grade violence, controlling for gender and earlier violent behavior (b = .88, p = .008). When included with race as a predictor, race was not significant (b = .60, p = .06). In a similar test, with income rather than race included as a predictor, income was also not significant (−.20, p = .174).

Discussion

Violence remains a serious problem that is not equally prevalent among Black and White adolescents. Understanding the mechanisms behind the differences in violent behavior between racial groups can allow us to more clearly specify prevention interventions. This study explored two mechanisms for the differences in violence perpetration between the two groups.

First, are there race differences in in exposure to risk factors? We found that Blacks are exposed to higher levels of risk factors such as low income and lower parent education. Black teens experienced more poverty, but also stronger family guidelines. Black teens were more likely to associate with peers with serious school trouble but not more likely to associate with peers involved with alcohol, marijuana, or delinquency. While Black parents report significantly higher levels of family guidelines, there were no differences in parental consequences, monitoring, or attachment to parents. There were, however, level differences in self-reported violent behavior when study participants were in eighth grade (Blacks reported higher frequency of violent behavior than Whites), suggesting the causal process of predictors tested here might be operating at an earlier time point for Black youth than for Whites.

The second question explored whether some risk factors are more salient in one racial group than the other. The MGCFA indicated that parent guidelines against substance use significantly loaded on parenting for Blacks but not for Whites. The structural model indicates that in addition to being male and prior violent behavior, parenting affected violence through its influence on ninth-grade peers. Interestingly, analyses suggest that income impacts violence through its positive relationship with parenting. Other research also suggests that differences in violent behaviors are attributable to family contexts after controlling for income inequality (Conger et al., 1992; Heimer, 1997). No race moderation was found, indicating that both Blacks and Whites are equally vulnerable to the effects of deviant peers on violent behavior.

We can conclude that race differences in violence at 10th grade are not attributable to lower exposure to skilled parenting or higher exposure to deviant peers since we don’t observe mean-level differences in either latent construct. Nor can we attribute the race difference in violence to greater vulnerability to parental or peer factors since race did not moderate the relationships between predictors and violent behavior. The models explain only between 24% and 30% of the variance in violent behavior. What can we make of the racial differences in violence that are not explained by parental and peer differences? We conducted a final set of analyses to further explore what might explain the race difference. We examined the five potential explanations based on race differences in mean levels of demographic and predictor variables. We found that income and race overlap in their explanation of variability in violent behavior to the extent that neither is a unique predictor in this study. Further, both race and income differences were potentially mediated by associating with friends who get in trouble at school (this is the one measure of deviant peers for which there were mean differences by race). The race effect still had a trend level (p < .10) association with violent behavior after controlling for friends who get in serious trouble at school, so caution interpreting this as full mediation for race is warranted. Perhaps this association is only partially mediated. However, the full mediation confirmed for income effects, and the fact that income and race effects are not clearly distinguishable in this sample adds support to the mediation hypothesis for both race and income.

Obviously other factors, which we have not explored in these analyses, should be considered. Likely candidates are other individual, social, and environment factors that may be different for Black and White adolescents. Examples of the former are educational experiences, attachment to school and teachers or academic success, or religious involvement. There is reason to suspect educational differences (Hirschi & Hindelang, 1977). We though, expect that race-based differences in environments offer more fruitful opportunities to explain why Black youth are more involved with violence than Whites after parenting and peers have been taken into account.

Why do we think this? Even though we have controlled for income here, Black adolescents more frequently live in “challenged” neighborhoods than do their White counterparts and this difference is not subsumed by income. There are both structural and cultural differences in these communities that make them qualitatively different beyond what is measured by family income. For example, Black communities are generally characterized by higher levels of social and economic disadvantage (Sampson, Morenoff, & Raudenbush, 2005), more labor market disadvantage (Crutchfield, 1989), and more of the forced migration produced by mass imprisonment out of and back into these neighborhoods (Clear, 2007). Culturally, the places where Black youths live are more likely to be characterized by the codes of the streets (Anderson, 1999) that emerge when residents experience prolonged profound disadvantage which in turn may explain higher exposure to friends who get in serious trouble at school. Fundamentally, American cities remain highly segregated (Massey & Denton, 1993), and we believe that the next steps towards expanding our understanding of observed racial difference in violence should begin with this essential feature of our social environment.

These findings suggest several implications for prevention. Simple analyses of income and race suggest that improving employment opportunity structures for Black parents should reduce the violence disparity. Further articulation of this finding through the structural model suggests that higher income may reduce violence through making it more likely that parents can accomplish good parenting practices and have time for bonding and monitoring their adolescent's activities. Further, our results suggest that programs that promote good parenting practices, including setting guidelines and providing consistent moderate monitoring and consequences and strong teen-parent bonds are likely to reduce violence through the impact on the type of peers with whom teens associate. (Haggerty et al., 2007; Windle et al., 2010). Finally, prevention programs that reduce the number of deviant peers or decrease the likelihood that teens associate with peers engaged in problem behaviors are likely to reduce teen violence (Botvin, Mihalic, & Grotpeter, 1998; Sussman, Rohrbach, & Mihalic, 2004).

The strengths of this study include using data from parent and teen reports, the longitudinal design, and the sample of equal numbers of Black and White families. Weaknesses include measurement of each construct at particular ages rather measures of all variables at all age points. Further, missing data were due to attrition over time, but also due to excluding teens who reported having no close friends in the ninth grade. This makes it impossible to say whether having deviant peers is better or worse than having no close friends at all. A final concern is that we did not examine neighborhood contexts which some suggest are important for understanding racial differences in violent behaviors (Sampson et al., 2005). Research suggests that Blacks are more likely to live in neighborhoods characterized by higher rates of poverty and neighborhood violence (Jargowsky, 1996; Massey, 1990). This sample comes from a Northwest city and caution should be taken in generalizing the findings to other geographic areas with different patterns of neighborhood racial disproportionateness.

In conclusion, the difference in self-reported violent behavior between Black and White 10th graders appears to be more related to income disparity than racial status. The impact of income on violence appears to be mediated by racially common processes of good parenting practices negatively impacting deviant peer association. The findings presented here shed light on the important contribution of parenting during middle adolescence on the selection of peers in early high school for both Black and White teens, and the direct impact of deviant peers on youth violence. This study adds information that this process applies to the prediction of violence, not just general delinquency as has been found by others, and that this process applies to both Blacks and Whites.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Grant # RO1-DA 021737-03 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented in June 2009 at the Society for Prevention Research annual meeting in Washington, DC.

Richard F. Catalano is a board member of Channing Bete Company, distributor of the Parents Who Care program which was tested as part of the study described in this paper.

References

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W.W. Norton; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Multivariate analysis with latent variables: causal modeling. Annual Review of Psychology. 1980;31:419–456. [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Beuhring T, Shew ML, Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Resnick MD. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1879–1884. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, Hofer SM. Assessing factorial invariance in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. In: Ong AD, van Dulmen M, editors. Oxford handbook of methods in positive psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Mihalic SF, Grotpeter JK. Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Five: Life Skills Training. Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado; Boulder, CO: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. In: Husén T, Postlethwaite TN, editors. International encyclopedia of education. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Elsevier; Oxford: 1994. pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth violence: facts at a glance. 2009 Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention.

- Choi Y, Harachi TW, Gillmore MR, Catalano RF. Are multiracial adolescents at greater risk? Comparisons of rates, patterns, and correlates of substance use and violence between monoracial and multiracial adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:86–97. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clear TR. How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield RD. Labor stratification and violent crime. Social Forces. 1989;68:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield RD, Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, McGlynn A, Catalano RF. Racial disparities in early criminal justice involvement. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1:218–230. doi: 10.1007/s12552-009-9018-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Flannery DJ. Youth violence prevention: Are we there yet? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:138–150. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence and Victims. 1989;4:79–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime in the United States. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2008/index.html.

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Degarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon Divorce Study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Stoolmiller M. Emotions as contexts for adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Diaz T, Miller NL. Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty KP, Skinner ML, MacKenzie EP, Catalano RF. A randomized trial of Parents Who Care: Effects on key outcomes at 24-month follow-up. Prevention Science. 2007;8:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, O'Donnell J, Abbott RD, Day LE. The Seattle Social Development Project: Effects of the first four years on protective factors and problem behaviors. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. Guilford Press; New York: 1992. pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl T, Farrington DP, Brewer D, Catalano RF, Harachi TW. A review of predictors of youth violence. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 106–146. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Payne DC. Race, friendship networks, and violent delinquency. Criminology. 2006;44:775–805. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Silver E, Teasdale B. Neighborhood characteristics, peer networks, and adolescent violence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2006;22:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer K. Socioeconomic status, subcultural definitions, and violent delinquency. Social Forces. 1997;75:799–833. [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Longitudinal family and peer group effects on violence and nonviolent delinquency. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:172–186. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Chung I-J, Guo J, Abbott RD, Hawkins JD. Protective factors against serious violent behavior in adolescence: A prospective study of aggressive children. Social Work Research. 2003;27:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Chung I-J, Nagin DS. Developmental trajectories of family management and risk for violent behavior in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Maguin E, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Developmental risk factors for youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:176–186. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, Hindelang MJ. Intelligence and delinquency: A revisionist review. American Sociological Review. 1977;42:571–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C-C, Pugh MD. Poverty, income inequality, and violent crime: A meta-analysis of recent aggregate data studies. Criminal Justice Review. 1993;18:182–202. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD. Modeling mediation in the etiology of violent behavior and adolescence: A test of the social development model. Criminology. 2001;39:75–107. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ, Loeber R, Hill KG, et al. Disproportionate minority contact in the juvenile justice system: A study of differential minority arrest/referral to court in three cities. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/grants/219743.pdf.

- Ingram JR, Patchin JW, Huebner BM, McCluskey JD, Bynum TS. Parents, friends, and serious delinquency: An examination of direct and indirect effects among at-risk early adolescents. Criminal Justice Review. 2007;32:380–400. [Google Scholar]

- Jargowsky PA. Take the money and run: Economic segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:984–998. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika. 1971;36:409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann DR, Wyman PA, Forbes-Jones EL, Barry J. Prosocial involvement and antisocial peer affiliations as predictors of behavior problems in urban adolescents: Main effects and moderating effects. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:417–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Graham JW, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Herrenkohl TI. Childhood risk factors for persistence of violence in the transition to adulthood: A social development perspective. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:355–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird R, Criss M, Pettit G, Dodge K, Bates J. Parents’ monitoring knowledge attenuates the link between antisocial friends and adolescent delinquent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Patterson GR. Parental management: Mediation of the effect of socioeconomic status on early delinquency. Criminology. 1990;28:301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mack KY, Leiber MJ, Featherstone RA, Monserud MA. Reassessing the family-delinquency association: Do family type, family processes, and economic factors make a difference? Journal of Criminal Justice. 2007;35:51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. The American Journal of Sociology. 1990;96:329–357. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Denton NA. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty TL, Bellair PE. Explaining racial differences in adolescent violence: Structural disadvantage, family well-being and social capital. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Latent variable modeling in heterogeneous populations. Psychometrica. 1989;54:557–585. [Google Scholar]

- Muuss R. Theories of adolescence. 6th ed. The McGraw-Hill Companies; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Preadolescent predictors of substance initiation: A test of both the direct and mediated effect of family social control factors on deviant peer associations and substance initiation. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:599–616. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ. Contributions of families and peers to delinquency. Criminology. 1985;23:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzanchera C. Juvenile arrests 2008. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, December 2009. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Ireland M, Borowsky I. Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:424, e1–424, e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush S. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different? Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:558–563. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Rohrbach L, Mihalic S. Project Towards No Drug Abuse: Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Twelve. Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado; Boulder, CO: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Youth violence: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Government Printing Office; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Warr M. Making delinquent friends: Adult supervision and children's affiliations. Criminology. 2005;43:77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Brener N, Cuccaro P, Dittus P, Kanouse DE, Murray N, et al. Parenting predictors of early-adolescents’ health behaviors: Simultaneous group comparisons across sex and ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:594–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]