Abstract

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized saline-controlled trials to determine the safety and efficacy of US-approved intra-articular hyaluronic acid (IAHA) injections for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. A total of 29 studies representing 4,866 unique subjects (IAHA: 2,673, saline: 2,193) were included. IAHA injection resulted in very large treatment effects between 4 and 26 weeks for knee pain and function compared to pre-injection values, with standardized mean difference (SMD) values ranging from 1.07–1.37 (all P < 0.001). Compared to saline controls, SMDs with IAHA ranged from 0.38–0.43 for knee pain and 0.32–0.34 for knee function (all P < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between IAHA and saline controls for any safety outcome, including serious adverse events (SAEs) (P = 0.12), treatment-related SAEs (P = 1.0), study withdrawal (P = 1.0), and AE-related study withdrawal (P = 0.46). We conclude that intra-articular injection of US-approved HA products is safe and efficacious in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, knee, meta-analysis, osteoarthritis, systematic review, viscosupplementation

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative disease in older adults that is characterized by joint pain and dysfunction due to progressive articular cartilage and subchondral bone damage, inflammation/synovitis, osteophyte formation, and joint space loss.1 Hyaluronic acid (HA) is an integral component of synovial fluid that acts as a joint lubricant during shear stress and a shock absorber during compressive stress. In the setting of knee OA, a marked reduction in concentration and molecular weight of endogenous HA ultimately leads to reduced viscoelastic properties of synovial fluid and induction of proinflammatory pathways.2 Intra-articular injection of exogenous HA is intended to replace this OA-induced deficit and to stimulate production of endogenous HA,3 which may alleviate symptoms of knee OA via multiple pathways including stimulation of chondrocyte metabolism, synthesis of articular cartilage matrix components, and inhibition of chondrodegradative enzymes and inflammatory processes.4

Intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid (IAHA) is classified as a medical device in the US and is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. Since medical devices are regulated by different regulatory bodies in different countries, the safety and efficacy profile of such products must be assessed by country. In their recent clinical practice guidelines for treatment of knee OA, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons stated “We cannot recommend using hyaluronic acid for the treatment of symptomatic knee OA”.5 Methodological issues related to the systematic review supporting this recommendation included only 14 studies, assessment of efficacy outcomes beyond 6 months, inclusion of HA products not commercially available in the US, and confusion in effect size interpretation. Therefore, a reevaluation of IAHA efficacy is warranted to address these concerns. A separate rationale for performing the current meta-analysis was that, despite extensive evidence to the contrary,6–12 the safety of IAHA for knee OA has recently been called into question.13 The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized saline-controlled trials was to determine the safety and efficacy of US-approved IAHA injections for symptomatic knee OA.

Methods

The PRISMA Statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses served as a template for this report.14 We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for randomized, saline-controlled trials of IAHA injection for treatment of knee OA using a combination of study design-, treatment-, and disease-specific keywords and MeSH terms. No date restrictions were applied to the searches. Reference lists of included papers and relevant meta-analyses were manually searched. The final search was conducted in June 2013.

The main inclusion criteria were injection of a US-approved HA product, randomized, saline-control study design, primary diagnosis of knee OA, identical treatment and follow-up conditions between IAHA and saline-control groups, and at least one extractable efficacy or safety outcome. Studies were excluded if concomitant interventional therapies were uniformly administered, the study was published in a non-English language journal, or if data were available only from abstracts, conference proceedings, websites, or personal communication.

Data were extracted from eligible peer-reviewed articles by one author (LM) and were verified by a second author (JB). Data extraction discrepancies between the two coders were determined by discussion and consensus. Methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Jadad score.15 Main efficacy outcomes included knee pain and knee function. These data were extracted in a non-biased manner using the knee OA outcome meta-analysis hierarchy of Juhl et al.16 Due to variations in reporting the post-injection knee pain and function trajectory, we stratified data into two post-injection time windows: 4–13 weeks and 14–26 weeks. Efficacy data reported outside of these windows were excluded. If a study reported multiple pain or function treatment effects within a given window, the final value for each was extracted for analysis purposes. Safety outcomes included serious adverse events (SAEs), treatment-related SAEs, subject withdrawals for any reason, and AE-related subject withdrawals occurring at any time during follow-up.

A random effects meta-analysis model was selected a priori for all analyses. For each efficacy outcome, we calculated two separate effect size statistics in each time window: (a) pre-treatment to post-treatment standardized mean difference (SMD) for IAHA and (b) SMD for IAHA vs. saline control. For reference, SMD values of 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, and 1.0 are defined as small, medium, large, and very large, respectively.17 For each safety outcome, the absolute risk difference (RD) was selected because this statistic considers data from all studies, including zero total event trials.18 When a single control group served multiple treatment groups within a study, the sample size of the control group entered into the meta-analysis was adjusted based on the number of treatment groups.19 Forest plots were used to visually assess the effect sizes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) across studies. We used the I2 statistic to estimate heterogeneity of treatment effects with values of ≤25%, 50%, and ≥75% representing low, moderate, and high inconsistency, respectively.20 Publication bias was visually assessed using funnel plots (not shown) and quantitatively assessed using Egger’s regression test.21P-values were two-sided with a significance level <0.05. All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 2.2, Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

After screening 1,653 records for eligibility, 29 randomized, saline-controlled trials22–50 reporting 38 treatment effects from 4,866 unique subjects (IAHA: 2,673, saline: 2,193) were included in the meta-analysis. The most common reasons for study exclusion included lack of a sham control group, nonrandomized design, or use of HA products not approved in the US. Baseline subject characteristics were similar between the IAHA and saline groups (Table 1). The most commonly studied viscosupplements were Hyalgan (18), Synvisc (9), Supartz/Artzal (6), Orthovisc (3), Gel-One (1), and Euflexxa (1). The total number of injections received by patients ranged from 1–5. Overall, the methodological quality of studies was medium, with a median Jadad score of 3 (range: 2–5).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | IAHA | Saline |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 2,673 | 2,193 |

| Age, yr, mean (min–max) | 65 (53–72) | 62 (53–73) |

| Female gender, %, median (min–max) | 64 (27–92) | 65 (22–100) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (min–max) | 28 (25–32) | 29 (25–33) |

| Symptom duration, yr, mean (min–max) | 4.5 (1.0–9.1) | 4.3 (0.8–8.5) |

| Kellgren-Lawrence grade, median (min–max) | 2.5 (1.9–3.0) | 2.5 (1.8–3.5) |

Abbreviation: IAHA, intra-articular hyaluronic acid.

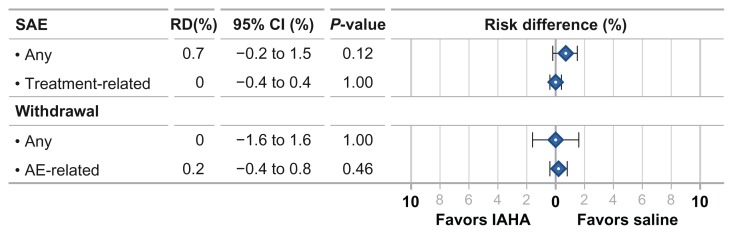

IAHA efficacy vs. pre-treatment

IAHA injection resulted in very large treatment effects for knee pain and knee function compared to pre-injection values. The SMD for knee pain was 1.37 at 4–13 weeks and 1.14 at 14–26 weeks (both P < 0.001). Treatment effects for knee function were slighter lower with SMDs of 1.16 and 1.07, respectively (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). There was high heterogeneity (I2 = 74%–92%, all P < 0.001) for all IAHA treatment effects with evidence of publication bias for knee pain, but not knee function, during both analysis windows.

Figure 1.

Standardized mean difference in pre-to-post efficacy changes with intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection.

Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference.

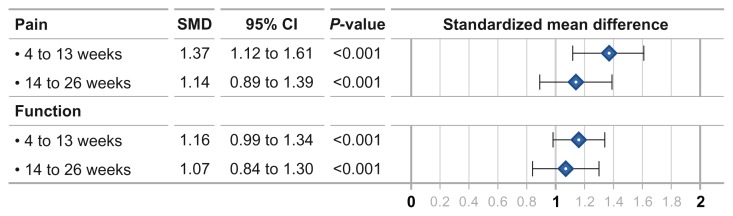

IAHA efficacy vs. saline control

Compared to saline controls, the SMD for knee pain was 0.43 at 4–13 weeks and 0.38 at 14–26 weeks (both P < 0.001). Knee function SMD was 0.34 and 0.32, respectively, at the same time intervals (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Heterogeneity among studies was high for knee pain (I2 = 73%–75%, both P < 0.001) and moderate for knee function (I2 = 54%–69%, both P < 0.01). Publication bias was evident for both knee pain treatment effects and for knee function at 4–13 weeks, but not for knee function at 14–26 weeks.

Figure 2.

Standardized mean difference in intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection vs. saline controls.

Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference.

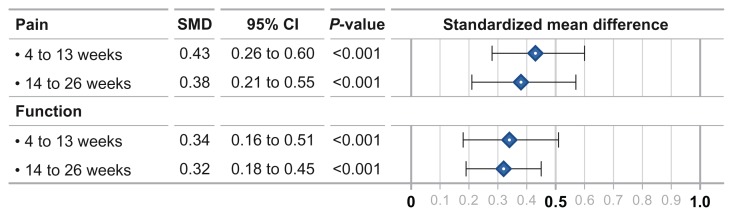

Safety outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between IAHA and saline controls for any safety outcome. The SAE risk was similar between IAHA and saline (RD = 0.7% (95% CI: −0.2%–1.5%, P = 0.12). No SAEs were determined to be related to injection of IAHA or saline. The risk of subject withdrawal from the study for any reason was identical between groups (RD = 0.0%, 95% CI: −1.6%–1.6%, P = 1.0). The risk of subject withdrawals due to an AE was also similar with IAHA vs. saline (RD = 0.2%, 95% CI: −0.4%–0.8%, P = 0.46) (Fig. 3). There was minimal heterogeneity among studies (all I2 = 0%) with no evidence of publication bias for any safety outcome. We conducted two sensitivity analyses for each safety outcome: the first in which the meta-analysis was re-estimated by removing one study at a time and the second in which odds ratios were used as the statistic of interest. The conclusions of the primary analysis were corroborated by both sensitivity analyses.

Figure 3.

Risk difference in safety outcomes for intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection vs. saline controls.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; IAHA, intra-articular hyaluronic acid; RD, risk difference; SAE, serious adverse event.

Discussion

We conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis of US-approved HA products on knee OA symptoms. Overall, we conclude that intra-articular injection of US-approved HA products is safe and efficacious in patients with symptomatic knee OA.

Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published on this topic over the last decade, with the SMD of IAHA versus a control group for efficacy outcomes ranging from 0.0–0.46.6,7,10,13,51 For comparison, the saline-adjusted SMD in the current meta-analysis ranged from 0.32–0.43, depending on outcome and time window. However, this statistic may underestimate the overall treatment effect of IAHA since control group improvements in pain and function are substantial in OA clinical trials, particularly when control treatments, such as saline, are administered via injections.52 There is a distinct difference between a pre-to-post treatment effect and a placebo-adjusted treatment effect; the former assesses the overall patient experience in the IAHA group while the latter teases out the independent effect of IAHA above and beyond that of saline, a statistic that is arguably irrelevant from the perspective of the patient. Thus, the efficacy results of the current meta-analysis can be best characterized by a very large treatment effect of US-approved IAHA injections on knee pain and function between 4 and 26 weeks and, after statistically adjusting for saline-control improvements, a medium treatment effect with US-approved IAHA during this same period.

Perhaps the most notable finding from this meta-analysis is that US-approved HA products are not associated with increased safety risks. This is in sharp contrast to Rutjes et al13 who concluded that IAHA injections increased the risk of SAEs and AE-related subject withdrawals. However, there were several important subtleties associated with their analysis. Although the calculated risk of SAEs was marginally higher with IAHA vs. controls, the association between SAE and treatment was not considered. In fact, in our analysis, 100% of reported SAEs were unrelated to treatment. Second, the safety analysis in the Rutjes paper was heavily influenced by inclusion of unpublished, unverifiable data. In contrast, we only included data from full-text manuscripts published in peer-reviewed journals. Lastly, Rutjes et al analyzed all safety data using an odds ratio, a statistic that excludes zero total event trials.18 Considering that 30 of 38 SAE treatment effects in the current meta-analysis reported zero total events, the odds ratio is arguably an inappropriate statistic for this type of analysis since most data are disregarded.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations that may influence interpretation. Most, but not all, studies excluded subjects with end-stage (Kellgren-Lawrence grade IV or equivalent) knee OA and, therefore, the efficacy of IAHA in these patients cannot be determined. Next, we did not consider HA products without US approval and, therefore, implied comparisons of safety and efficacy between US approved vs. non-US approved products should be performed with caution. Due to sample size considerations, we did not attempt to analyze treatment effects by HA brand. Lastly, efficacy outcomes were inconsistent across studies and publication bias was evident for knee pain outcomes. Strengths of this meta-analysis are inclusion of only randomized, saline-controlled trials, structured data extraction methodology, inclusion of all zero total event trials in safety analyses, and sensitivity analyses that accounted for choice of statistical test and potentially influential studies.

Overall, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, saline-controlled trials confirms that intra-articular injection of US-approved HA products is safe and efficacious in patients with symptomatic knee OA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Randy Asher for assistance with graphical illustrations.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: LM, JB. Analyzed the data: LM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: LM. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: JB. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: LM, JB. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: LM, JB. Made critical revisions and approved final version: LM, JB. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the HA Viscosupplement Coalition (Bioventus LLC, Durham, NC; DePuy Synthes Mitek Sports Medicine, Raynham, MA; Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Parsippany, NJ; Fidia Pharma USA, Inc., Parsippany, NJ; Zimmer, Inc., Warsaw, IN).

References

- 1.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005;365(9463):965–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahl LB, Dahl IM, Engstrom-Laurent A, Granath K. Concentration and molecular weight of sodium hyaluronate in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other arthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44(12):817–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.12.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MM, Ghosh P. The synthesis of hyaluronic acid by human synovial fibroblasts is influenced by the nature of the hyaluronate in the extracellular environment. Rheumatol Int. 1987;7(3):113–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00270463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg VM, Buckwalter JA. Hyaluronans in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence for disease-modifying activity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(3):216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline. 2013. [Accessed date May 28, 2013]. http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/TreatmentofOsteoarthritisoftheKneeGuideline.pdf.

- 6.Arrich J, Piribauer F, Mad P, Schmid D, Klaushofer K, Müllner M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2005;172(8):1039–43. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannuru RR, Natov NS, Dasi UR, Schmid CH, McAlindon TE. Therapeutic trajectory following intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection in knee osteoarthritis—meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19(6):611–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bannuru RR, Natov NS, Obadan IE, Price LL, Schmid CH, McAlindon TE. Therapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(12):1704–11. doi: 10.1002/art.24925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colen S, van den Bekerom MP, Mulier M, Haverkamp D. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis with emphasis on the efficacy of different products. BioDrugs. 2012;26(4):257–68. doi: 10.2165/11632580-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;290(23):3115–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.23.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichenbach S, Blank S, Rutjes AW, et al. Hylan versus hyaluronic acid for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1410–8. doi: 10.1002/art.23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang CT, Lin J, Chang CJ, Lin YT, Hou SM. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(3):538–45. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):180–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhl C, Lund H, Roos EM, Zhang W, Christensen R. A hierarchy of patient-reported outcomes for meta-analysis of knee osteoarthritis trials: empirical evidence from a survey of high impact journals. Arthritis. 2012;2012:136245. doi: 10.1155/2012/136245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedrich JO, Adhikari NK, Beyene J. Inclusion of zero total event trials in meta-analyses maintains analytic consistency and incorporates all available data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Accessed date May 28, 2013]. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Updated Mar 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman RD, Moskowitz R. Intraarticular sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Hyalgan Study Group. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(11):2203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman RD, Rosen JE, Bloch DA, Hatoum HT, Korner P. A double-blind, randomized, saline-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of EUFLEXXA for treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee, with an open-label safety extension (the FLEXX trial) Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bragantini A, Cassini M, de Bastiani G, Perbellini A. Controlled single-blind trial of intra-articularly injected hyaluronic acid (HyalganÒ*) in osteo-arthritis of the knee. Clinical Trials Journal. 1987;24(4):333–40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandt KD, Block JA, Michalski JP, Moreland LW, Caldwell JR, Lavin PT. Efficacy and safety of intraarticular sodium hyaluronate in knee osteoarthritis. ORTHOVISC Study Group. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(385):130–43. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunyaratavej N, Chan KM, Subramanian N. Treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee with hyaluronic acid. Results of a multicenter Asian study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84(Suppl 2):S576–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrabba M, Paresce E, Angelini M, Re KA, Torchiana EEM, Perbellini A. The safety and efficacy of different dose schedules of hyaluronic acid in the treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee with joint effusion. European Journal of Rheumatology and Inflammation. 1995;15(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cubukçu D, Ardiç F, Karabulut N, Topuz O. Hylan G-F 20 efficacy on articular cartilage quality in patients with knee osteoarthritis: clinical and MRI assessment. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24(4):336–41. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-1043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day R, Brooks P, Conaghan PG, Petersen M. A double blind, randomized, multicenter, parallel group study of the effectiveness and tolerance of intraarticular hyaluronan in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(4):775–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeCaria JE, Montero-Odasso M, Wolfe D, Chesworth BM, Petrella RJ. The effect of intra-articular hyaluronic acid treatment on gait velocity in older knee osteoarthritis patients: a randomized, controlled study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diracoglu D, Vural M, Baskent A, Dikici F, Aksoy C. The effect of viscosupplementation on neuromuscular control of the knee in patients with osteoarthritis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.3233/BMR-2009-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grecomoro G, Martorana U, Di Marco C. Intra-articular treatment with sodium hyaluronate in gonarthrosis: a controlled clinical trial versus placebo. Pharmatherapeutica. 1987;5(2):137–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson EB, Smith EC, Pegley F, Blake DR. Intra-articular injections of 750 kD hyaluronan in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a randomised single centre double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 91 patients demonstrating lack of efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53(8):529–34. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.8.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang TL, Chang CC, Lee CH, Chen SC, Lai CH, Tsai CL. Intra-articular injections of sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan®) in osteoarthritis of the knee. a randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial in the Asian population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huskisson EC, Donnelly S. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(7):602–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.7.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jørgensen A, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Simonsen O, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan is without clinical effect in knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 337 patients followed for 1 year. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1097–102. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jubb RW, Piva S, Beinat L, Dacre J, Gishen P. A one-year, randomised, placebo (saline) controlled clinical trial of 500–730 kDa sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan) on the radiological change in osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57(6):467–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlsson J, Sjögren LS, Lohmander LS. Comparison of two hyaluronan drugs and placebo in patients with knee osteoarthritis. A controlled, randomized, double-blind, parallel-design multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41(11):1240–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.11.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotevoglu N, Iyibozkurt PC, Hiz O, Toktas H, Kuran B. A prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing the efficacy of different molecular weight hyaluronan solutions in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26(4):325–30. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kul-Panza E, Berker N. Is hyaluronate sodium effective in the management of knee osteoarthritis? A placebo-controlled double-blind study. Minerva Med. 2010 Apr;101(2):63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohmander LS, Dalén N, Englund G, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicentre Trial Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(7):424–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.7.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundsgaard C, Dufour N, Fallentin E, Winkel P, Gluud C. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate 2 mL versus physiological saline 20 mL versus physiological saline 2 mL for painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(2):142–50. doi: 10.1080/03009740701813103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrella RJ, Cogliano A, Decaria J. Combining two hyaluronic acids in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(8):975–81. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puhl W, Bernau A, Greiling H, et al. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, double-blind study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1993;1(4):233–41. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rolf CG, Engstrom B, Ohrvik J, Valentin A, Lilja B, Levine DW. A comparative study of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronan viscosupplements and placebo in patients with symptomatic and arthroscopy-verified cartilage pathology. Journal of Clinical Research. 2005;8:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scale D, Wobig M, Wolpert W. Viscosupplementation of osteoarthritic knees with hylan: a treatment schedule study. Current Therapeutic Research. 1994;55(3):220–32. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strand V, Baraf HS, Lavin PT, Lim S, Hosokawa H. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial comparing a single intra-articular injection of Gel-200, a new cross-linked formulation of hyaluronic acid, to phosphate buffered saline for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012 May;20(5):350–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wobig M, Dickhut A, Maier R, Vetter G. Viscosupplementation with hylan G-F 20: a 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther. 1998;20(3):410–23. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu JJ, Shih LY, Hsu HC, Chen TH. The double-blind test of sodium hyaluronate (ARTZ) on osteoarthritis knee. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1997;59(2):99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sala SF, Miguel RE. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a short term study. Eur J Rheum Inflammation. 1995;15:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maratea D, Fadda V, Trippoli S, Messori A. Viscosupplementation in patients with knee osteoarthritis: temporal trend of benefits assessed by meta-regression. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Robertson J, Jones AC, Dieppe PA, Doherty M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(12):1716–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]