Abstract

Patient: Male, 48

Final Diagnosis: Low dose cyclophosphamide-induced acute hepatotoxicity

Symptoms: Epigastric pain

Medication: Withdrawal of cyclophosphamide

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Nephrology • Hepatology • Gastroenterology • Toxicology

Objective:

Unexpected drug reaction

Background:

Cyclophosphamide is commonly used to treat cancers, systemic vasculitides, and kidney diseases (e.g., lupus nephritis and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis). Acute adverse effects include bone marrow suppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, nausea, vomiting, and hair loss. Hepatotoxicity with high dose cyclophosphamide is well recognized but hepatitis due to low dose cyclophosphamide has rarely been described.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 48-year-old Chinese man with a rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis who developed severe acute hepatic failure within 24 hours of receiving low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. The diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis was supported with a positive c-ANCA serology. The patient was treated with high dose methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, intermittent hemodialysis, and low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide.

Conclusions:

Hepatotoxicity may occur even after low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of severe, non-viral, liver inflammation developing within 24 hours of administration of low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide (200 mg). Physicians should be aware of this serious adverse reaction and should not repeat the cyclophosphamide dose when there is hepatotoxicity caused by the first dose. Initial and follow-up liver function tests should be monitored in all patients receiving cyclophosphamide treatment.

Keywords: hepatotoxicity, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, cyclophosphamide

Background

Cyclophosphamide is a synthetic nitrogen mustard-like alkylating agent commonly used to treat cancers [1]. It is also used to treat systemic vasculitides and kidney diseases (e.g., lupus nephritis, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis) [2,3].

Acute adverse effects include bone marrow suppression with opportunistic infections, hemorrhagic cystitis, temporary infertility, nausea, vomiting, and hair loss [3]. However, pneumonitis and liver or cardiac toxicity are rare. The long-term effect of cyclophosphamide (especially with cumulative doses) is an increased incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome, lymphoma, bladder carcinoma, and permanent infertility after several years of treatment [3].

Hepatotoxicity with high-dose cyclophosphamide is well recognized, but hepatitis due to low-dose cyclophosphamide immediately after treatment has rarely been described [4,5].

We report here a patient with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and secondary granulomatosis with polyangiitis who developed acute severe hepatic failure within 3 hours of receiving low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute hepatitis occurring within 24 hours of treatment.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Chinese construction worker presented to the orthopaedic unit with a 1-month history of bilateral lower limbs weakness, numbness, pain, and progressive difficulty in walking. His past medical history included smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years ago, for which he completed 6 months of anti-TB treatment. Four months prior to this presentation, he was diagnosed with right eye scleritis and 1 month later he diagnosed with “late onset of bronchial asthma” when he presented with recurrent cough and difficulty in breathing. He denied any history of alcohol consumption, recreational drug abuse, or use of traditional medication. He was a chronic smoker (20 packs per year), was married, and had 2 children.

Physical examination showed that he was afebrile, with the blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. There were no oral ulcers, malar rash, or alopecia, but he had a vasculitic rash on his palms and feet. His left upper limb and both lower limbs appeared wasted, with bilateral foot drop. Cardiorespiratory examination revealed a systolic murmur at the left sternal edge and bronchial breath sounds bilaterally in the upper zones with no rhonchi. Results of abdominal examination were unremarkable.

His initial lab results were:

- Full blood count:

- Hemoglobin: 11.2 g/dl (14.0–17.0),

- White cell count: 16.2×109/L (4.0–10.0),

- Platelet: 752×109/L (150–400),

- Eosinophil: 3.1×109/L (0.02–0.5),

- Renal Profile:

- Urea: 6.6 mmol/L (2.5–6.4),

- Sodium: 131 mmol/L (135–150),

- Potassium: 5.1 mmol/L (3.5–5.0),

- Creatinine: 116 umol/L (62–106),

- Calcium: 2.23 mmol/L (2.14–2.58),

- Liver Function Test (LFT):

- Total Protein: 72 g/L (67–88),

- Albumin: 31 g/L (35–50),

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP): 190 U/L (32–104),

- Alalinetransaminase (ALT): 27 U/L (<44),

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): 119 mm/hr.

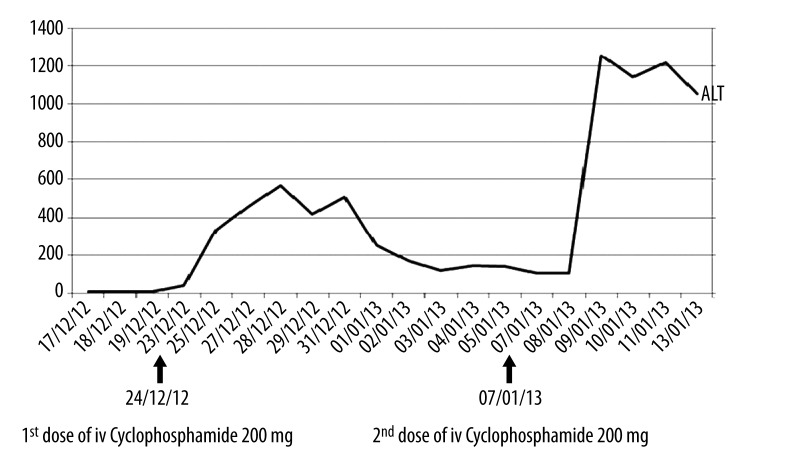

His chest X-ray is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chest X-Ray: Anterior Posterior (AP) Portable demonstrating multiple cavitating lesion involving right upper zone with surrounding fibrosis (arrow). Reticulonodular opacities seen involving the left mid and lower zones.

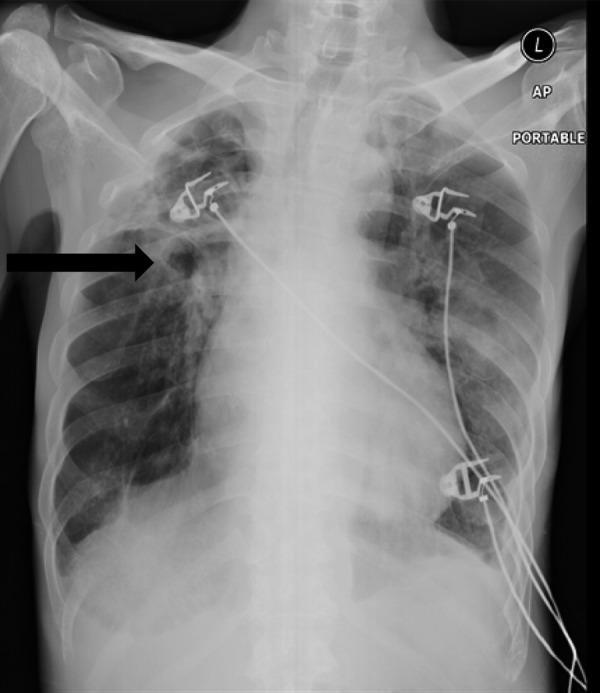

He treated as having reactivation of pulmonary TB with possible spinal TB spine with involvement of L4/L5 nerve root compression with 4 anti-TB medications. However, he remained febrile in the ward and a CT scan of the thorax revealed a large cavity in the apical segment, measuring 4.9×4.8×3.5 cm, with an intracavitary lesion measuring 1.9×1.1 cm. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Computerised Tomography scan of thorax showing a large cavity in the apical segment measures 4.9×4.8×3.5 cm (AP×W×CC).There is a intracavitary lesion measuring 1.9×1.1 cm within may represent fungal ball/aspergilloma (arrow).

There were multiple cystic air spaces in his right upper lobe, with thickened bronchial wall and traction fibrotic bands – cystic bronchiectasis and multiple nodules in the right middle lobe, the left upper lobe, and lower the lobe. The overall impression was of right apical old pulmonary TB changes with Mycetoma and cystic bronchiectasis. Oral itraconazole 200 mg bd was started. Aspergillus antibody was positive and bronchial alveolar lavage grew candida albicans.

Nerve conduction study revealed an axonal sensory-motor polyneuropathy over both lower limbs and a left ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. A diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy secondary to possible vasculitis with multiorgan involvement was considered. Autoimmune screening showed a negative antinuclear antibody (ANA) and normal complement levels but positive rheumatoid factor. His eosinophilia was persistently elevated (3.1×109/L) and c-ANCA was positive. His urine analysis showed protein 1+ and blood 3+ with a 24-hour urine protein excretion of 1 g/day. Sural nerve biopsy was suggestive of vasculitis. The diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis involving nerves, lungs, and kidneys was considered. He was empirically treated with high-dose pulse methylprednisolone and a few sessions of plasma exchange as his kidney function progressively deteriorated. He also required intermittent hemodialysis. An urgent renal biopsy was planned but, unfortunately, he developed acute chest pain with an acute coronary syndrome. Echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 20% with global hypokinetic walls, dilated chambers, moderate mitral regurgitation, and severe tricuspid regurgitation.

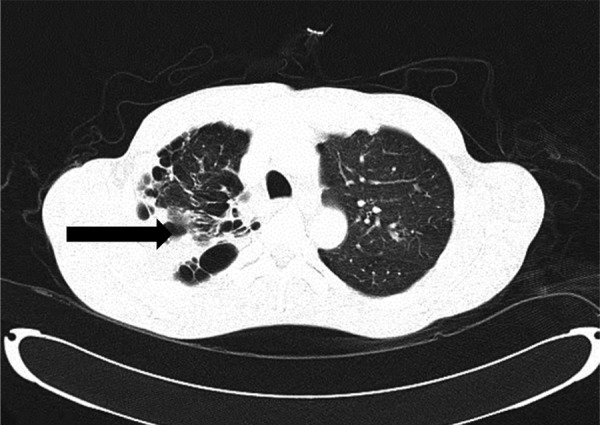

He was started on low-dose IV cyclophosphamide 200 mg due to concomitant respiratory infection and renal failure. He developed severe epigastric pain, dyspnea, and diarrhoea 3 hours after completion of IV cyclophosphamide, which resolved after 4 hours with symptomatic treatment. His liver enzymes showed a sudden elevation of alalinetransaminase (ALT) from 41 U/L to 336 U/L the next day and peaked at 568 U/L 4 days after administration of IV cyclophosphamide.

His anti-TB and antifungal medications were withheld and a liver ultrasound showed normal liver echotexture. Hepatitis B and C and HIV screening results were negative. His ALT improved to 104 U/L after 2 weeks of treatment and we proceeded with a second dose of IV cyclophosphamide 200 mg. He complained of similar symptoms following this and his ALT rose to 1253 U/L the next day. A diagnoses of cyclophosphamide-induced hepatitis was made. Cyclophosphamide was stopped. We were unable to perform a liver biopsy due to a coagulopathy. The trend of his liver enzyme (ALT) is shown in Figure 3. Subsequently, the patient developed hospital-acquired pneumonia and died due to another episode of acute coronary syndrome.

Figure 3.

Trend of the Alalinetransaminase (ALT) after intravenous Cyclophosphamide.

Discussion

We report a case of acute hepatitis shortly after low-dose IV cyclophosphamide, which is rarely described in the literature. Cyclophosphamide is administered either as intermittent pulses (intravenous) or a continuous oral low-dose regimen, depending on the indication for it use. Two well recognized dose-related adverse effects of cyclophosphamide are bone marrow suppression and hepatic injury [6,7]. High-dose cyclophosphamide may cause transient hepatitis. However, hepatotoxicity related to low-dose IV cyclophosphamide administration has rarely been reported. In this case, injury to the liver occurred within 24 hours after administration of low-dose cyclophosphamide. Akay et al. reported a patient with scleroderma who developed acute hepatitis after 6 weeks of low-dose oral cyclophosphamide 100 mg daily [8]. Synder et al reported a case of cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity after 5 weeks of oral cyclophosphamide 100 mg/day in a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis [1,9]. Our patient is different from these 2 cases in that he developed hepatitis within 24 hours after the first dose of IV cyclophosphamide, which worsened after the second dose. In this patient, a lower dose of IV cyclophosphamide was used rather than the standard dose due to concomitant infection and renal failure.

Although our patient received anti-TB and antifungal medication and corticosteroids, in addition to Cyclophosphamide, which could be cause for the hepatitis, we believe IV cyclophosphamide is the culprit. This is because the patient had been on anti-TB and antifungal medications for almost 1 month prior to IV cyclophosphamide, and liver function tests were normal until the administration of IV cyclophosphamide. It is well documented that hepatotoxicity usually happens within first 2 weeks of initiation of anti-TB or antifungal medication [10,11]. Additionally, when the patient was rechallenged with the second dose of IV cyclophosphamide, he had not received anti-TB and antifungal medications in the preceding 2 weeks. The ALT had nearly normalized at the time the patient received the second dose of IV cyclophosphamide and on this occasion he developed a similar hepatitis, which was more profound. We can therefore confidently conclude that both anti-TB and antifungal therapy were not responsible for the hepatitis in this patient. Rather than causing hepatitis, corticosteroids may mask the symptoms of drug-induced liver injury and anaphylaxis [12]. Therefore, the only possible cause for hepatitis in our patient seems to be cyclophosphamide therapy.

The mechanism of cyclophosphamide-induced hepatitis is not clearly understood. Cyclophosphamide is extensively metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 system. This probably induces sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, leading to a direct toxic effect on sinusoidal cells in the liver, thereby causing necrosis, obstruction, and obliteration of hepatic veins [13,14].

Martinez-Gabarron [15] reported a case that developed acute hepatitis with cholestasis after the first dose of cyclophosphamide (500 mg),and then resolved within a few days. Fifteen days later, the second cyclophosphamide bolus was given (750 mg), and the patient developed acute hepatitis with cholestasis, which normalized a few days after withdrawing cyclophosphamide.

Conclusions

Hepatotoxicity may occur even after low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide treatment. Improvements in disease management should include increased awareness of treatment-related toxicity and its prevention. Physicians should be aware of this potentially serious adverse reaction and should not repeat the cyclophosphamide dose when there is hepatotoxicity caused by the first dose. Initial and follow-up liver function tests should be monitored in all patients receiving cyclophosphamide treatment. In the future, advances in pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics may help determine the individual variations in drug response, and conceivably identify the likelihood of an adverse reaction[16].

References:

- 1.Ponticelli C, Passerini P. Alkylating agents and purine analogues in primary glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1991;6:381–88. doi: 10.1093/ndt/6.6.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukhtyar C, Guillevin L, Cid MC, et al. for the European Vasculitis Study Group EULAR recommendations for the management of primary small and medium vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(3):310–17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.088096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haubitz M. Acute and Long term Toxicity of cyclophosphamide. Transplantationsmedizin. 2007.

- 4.Cleland BD, Pokorny CS. Cyclophosphamide related hepatotoxicity. NZ J Med. 1993;23:408. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muratori L, Ferrari R, Muratori P, et al. Acute icteric hepatitis induced by a short course of low-dose cyclophosphamide in a patient with lupus nephritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(12):2364–65. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraiser LH, Kanekal S, Kehrer JP. Cyclophosphamide toxicity. Characterizing and avoiding the problem. Drugs. 1991;42:781–95. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turnbull J, Harper L. Adverse effects of therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(3):391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akay H, Akay T, Secilmis S, et al. Hepatotoxicity after low dose cyclophosphamide therapy. South Med J. 2006;99:1399–400. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000251467.62842.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Synder LS, Heigh RI, Anderson ML. Cyclophosphamide induced hepatotoxicity in a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:1203–4. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: fatal and severe liver injuries associated with rifampin and pyrazinamide for latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:998–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denning DW, Lee JY, Hostetler JS, et al. NIAID mycoses study group multi-center trial of oral itraconazole for invasive aspergillosis. Am J Med. 1994;97:135–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisker-Melman M, Hoofnagle JH. Phenytoin hepatotoxicity masked by corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1196–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonge ME, Huitema AD, Beijnen JH, Rodenhuis S. High exposures to bioactivated cyclophosphamide are related to the occurrence of veno-occlusive disease of the liver following high-dose chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1226–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald GB, Slattery JT, Bouvier ME, et al. Cyclophosphamide metabolism, liver toxicity, and mortality following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;101:2043–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Gabarron M, Enriquez R, Sirvent AE, et al. Hepatotoxicity following cyclophosphamide treatment in a patient with MPO-ANCA vasculitis. Nefrologia. 2011;31(4):496–98. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.May.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto N, Ludeman SM, Dolan ME. Drug focus: Pharmacogenetic studies related to cyclophosphamide-based therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1897–903. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]