Abstract

The approach of local drug delivery from polymeric coating is currently getting significant attention for both soft and hard tissue engineering applications for sustained and controlled release. The chemistry of the polymer and the drug, and their interactions influence the release kinetics to a great extent. Here, we examine lovastatin release behaviour from polycaprolactone (PCL) coating on β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). Lovastatin was incorporated into biodegradable water insoluble PCL coating. A burst and uncontrolled lovastatin release was observed from bare β-TCP, whereas controlled and sustained release was observed from PCL coating. A higher lovastatin release was observed pH 7.4 as compared to pH 5.0. Effect of PCL concentration on lovastatin release was opposite at pH 7.4 and 5.0. At pH 5.0 Lovastatin release was decreased with increasing PCL concentration, whereas release was increased with increasing PCL concentration at pH 7.4. High Ca2+ ion concentration due to high solubility of β-TCP and degradation of PCL coating were observed at pH 5.0 compared to no detectable Ca2+ ion release and visible degradation of PCL coating at pH 7.4. The hydrophilic-hydrophobic and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions between lovastatin-PCL were found to be the key factors controlling the diffusion dominated release kinetics of lovastatin from PCL coating over dissolution and degradation processes. Understanding the lovastatin release chemistry from PCL will be beneficial for designing drug delivery devices from polymeric coating or scaffolds.

Keywords: Lovastatin, polycaprolactone (PCL), release, drug-polymer interactions, hydrophobicity-hydrophilicity

1. Introduction

Small osteogenic drug molecules are increasingly being investigated for their potential applications in tissue engineering for hard tissue repair or regeneration. Statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMGCoA) reductase inhibitors, a family of small molecules were first introduced for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia [1,2]. Inhibition of HMGCoA stops the synthesis of downstream intermediate biomolecules in the mevalonate pathway required for cholesterol synthesis [3]. Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, a downstream intermediate of the mevalonate pathway, has stimulatory effect on osteoclasts activities [4]. Thus, statins suppress osteoclasts activity by preventing geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthesis through HMGCoA inhibition. It has also been shown that this inhibition of HMGCoA by statins enhances osteoblast differentiation through the activation of bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) promoter [5, 6], and stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in osteoblasts [7]. This dual effect, inhibitory on osteoclasts and stimulatory on osteoblasts, is beneficial for rapid wound/fracture healing [2, 8] especially to the osteoporotic patients. Osteoporosis is considered as the most common type of bone disease. Loss in density of bone tissue over time caused by osteoporosis makes bone thinner, brittle and eventually very prone to fracture [9]. This is caused by an imbalance between bone deposition by osteoblast cells, and bone resorption by osteoclast cells. This imbalance is the result of increased bone resorption.

Excellent bioactivity and compositional similarities between calcium phosphates (CaPs) and mineral component of bone makes CaPs suitable for hard tissue repair and regeneration. CaPs are osteoconductive but not osteoinductive. Osteogenic drugs and/or growth factors are used with implanted CaP biomaterials to induce osteoinductivity for accelerated healing. Due to low bioavailability and other associated potential side effects [10], local application of osteogenic drugs is more effective for tissue-material integration at the implant site. Local application of statins induces osteogenesis by promoting recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of osteogenic cells [6, 10]. Therefore, osteoinductive effect of statins [11] results in improved osseointregation at the implant or defect site through increased peri-implant bone density [12] due to increased new bone formation [6].

Sustained and controlled release of any drug over desired period of time from implant material is an important factor for effective osteogenesis. Therefore, any burst release of drug is not desired in achieving this goal. Bioactive and biodegradable polymer coating over CaP ceramic scaffolds is an approach to prevent the burst release [13, 14]. Incorporation of drug molecules into a thin polymer coating is also a potential approach to control drug release behavior [15]. Because of inherent biodegradability, biocompatibility, low cost, ease of process ability and non-toxicity, semi-crystalline polycaprolactone (PCL) has widely been explored for its potential use as drug carriers and scaffolding materials for both soft and hard tissue repair and regeneration [16–18].

Sustained and controlled local delivery of osteogenic and/or angiogenic growth factors and drugs from biodegradable polymers can accelerate bone regeneration and cartilage defects healing. Drugs or growth factors delivery through biodegradable polymers is an effort to ensure the release at a desirable rate and concentration at the application site to initiate accelerated osteogenesis and/or angiogenesis. However, there is a need to understand how polymeric matrix concentration and pH of the release media affects drug release behavior. Here, we examine the release behavior of lovastatin, a lipophilic statin, from a PCL coating on β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). Our objective was to understand the release chemistry of lovastatin, when incorporated into PCL coating. Effects of PCL percentage in the coating, varied lovastatin concentration, and pH of the release media on the release behavior were investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scaffold fabrication

Commercially available β-TCP powder with an average particle size of 550 nm (Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials Inc., Berkeley, CA) was used. Disc samples [12 mm (φ) X 1 mm (h)] from pure β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) powder were made by uniaxial press. These β-TCP discs underwent cold isostatic pressing (CIP) at 50 psi for 5 minutes, and then sintered at 900°C for 1 h (sintering cycles: heating rate 3°/min up to 120 °C, dwell time at 120 °C: lh; then heating rate 3°/min up to 600 °C, dwell time at 600 °C: lh, then heating rate 1°/min up to 900 °C, dwell time: lh, cooling rate: 10°/min). Relative bulk densities of the sintered scaffolds were determined using mass and physical dimensions of the scaffolds, and then normalized by the theoretical density (3.07 g/cm3) of β-TCP.

2.2.PCL coating and lovastatin incorporation

PCL (Mw=14000) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and lovastatin (active hydroxyl acid form) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) were used in this study. Three different PCL concentrations in acetone (w/v), 5%, 7.5% and 10% with constant lovastatin concentration, 100 µg per sample in each case, were used in this study to examine the effect of PCL concentration on lovastatin release kinetics. 7.5 % PCL concentration was selected to study the effect of lovastatin release from PCL with varied lovastatin concentration: 100 µg, 200 µg and 300 µg. PCL and lovastatin were dissolved in acetone to make 5 %, 7.5 %, and 10 % PCL solution (w/v) containing 100 µg lovastatin in 100 µL of each of this solution. For control samples, lovastatin was dissolved in acetone in absence of PCL containing 100 µg lovastatin in 100 µL acetone. Disc β-TCP samples were coated by pipetting 50 µL of above solutions on each side. Samples were air dried and then kept in a desiccator.

2.3.Coating morphology

Surface morphologies of disc compacts of all compositions were observed under a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) (FEI Inc., OR, USA), equipped with an ETD (Everhart-Thornley Detector) following gold sputter-coating (Technics Hummer V, San Jose, CA, USA). Surface topographic image of the coating was observed by atomic force microscope (AFM) equipped with a PicoForce scanning probe microscope with a Nanoscope IIIa controller and extender module (Bruker AXS Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). AFM was operated in contact mode in air using commercial silicon nitride cantilever probes. Scan rate, drive amplitude, feedback setpoint and gain parameters were optimized so that the AFM probe was able to track the coating surface at high resolution and low noise.

2.4.Lovastatin Release

Two different 0.1 M pH buffers were used to measure the release of lovastatin. A pH 7.4 phosphate buffer was used to mimic the physiological pH, whereas pH 5.0 acetate buffer was used to investigate lovastatin release in slightly acidic environment to mimic the condition right after surgery. The pH was measured with a pH probe to ensure the pH was within ±0.05 pH. Prior to starting the release study, each sample was rinsed with lmL of deionized water twice to wash off any loosely held lovastatin. Washed away lovastatin was determined from this 2 mL wash solution for each sample and subtracted from the loaded amount. Final release amount or percentage was calculated based on the remaining amount. Three samples from each concentration of PCL (0%, 5%, 7.5%, and 10% PCL) with 100µg lovastatin were placed in 2 mL of pH 7.4 phosphate buffer in individual vials. Three samples from each concentration were also placed in 2 mL of pH 5 acetate buffer in individual vials. Additionally, for the varied drug concentration, 3 samples of each drug concentration with 7.5% PCL coating were placed in 2 mL of pH 7.4 phosphate and pH 5 acetate buffer, respectively, in individual vials. Vials were labeled with the sample number, pH of buffer, PCL concentration, and the drug concentration. These vials were then kept at 37 °C under 150 rpm constant shaking. For the study of varying PCL concentration with constant lovastatin amount, the buffer solutions were changed at 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 144, and 192 hours. At each time point, the 2mL of buffer solution was replaced with a fresh 2 mL buffer solution. For varying lovastatin concentration with fixed PCL concentration, the buffer solutions were changed at 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24, 48, and 144 hours. Lovastatin concentration was measured at 239 nm wavelength by a Biotek Synergy 2 SLFPTAD microplate reader (Bioteck, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.5. Phase, Ca2+ concentration, and surface morphology after release

Phase analysis of sintered β-TCP scaffolds was conducted by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Philips PW 3040/00 Xpert MPD system (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) with Cu Ka radiation and Ni filter. Samples were scanned over a range of 20° to 60° at a step size of 0.05° and a count time of 1 s per step. Ca2+ ion concentration in the release media was measured using a Shimadzu AA-6800 atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Surface morphologies of all scaffolds after release were observed under a field emission scanning electron microscope as described above. For this, scaffolds were air dried at room temperature for 72 h after the release experiment was done. Scaffolds were then kept in a desiccator for further analysis.

3. Results

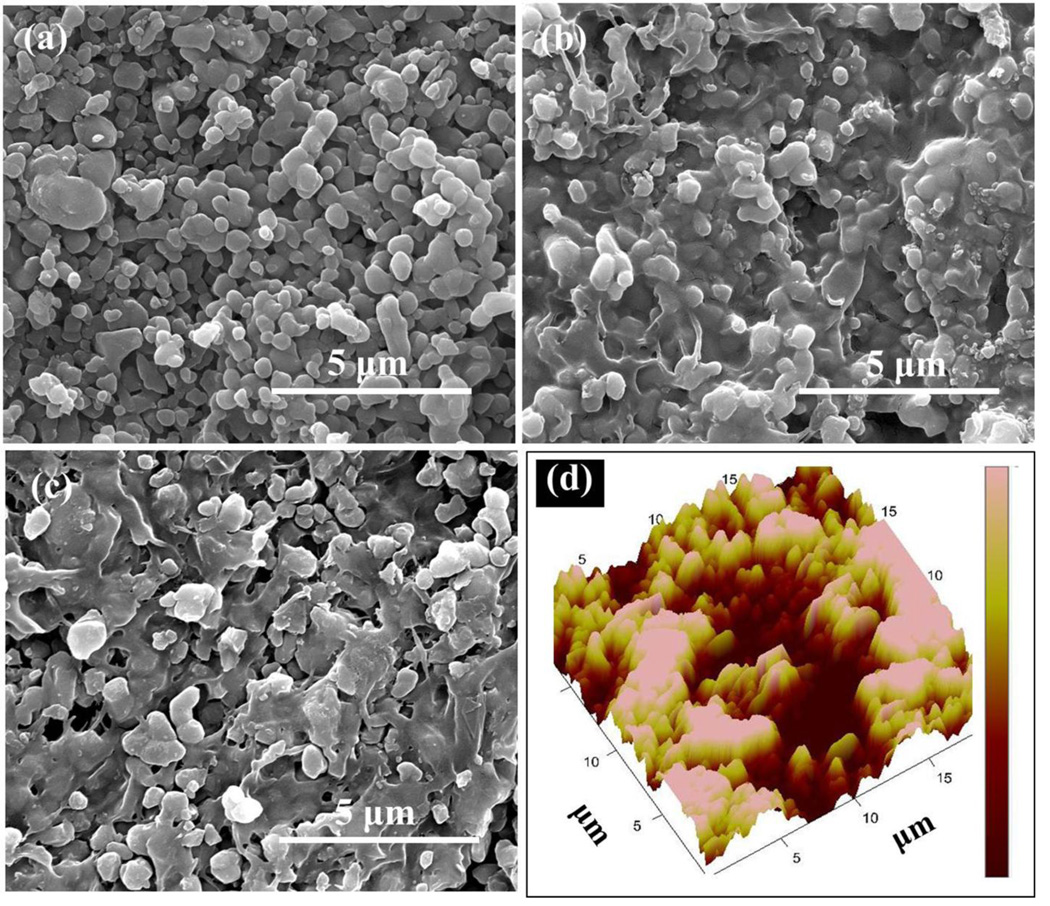

Figure 1(a–c) shows the SEM morphologies of the uncoated bare β-TCP, β-TCP coated by 5% PCL solution in acetone (w/v), and β-TCP coated by 5% PCL solution in acetone (w/v) containing 100 µg lovastatin (LOV) in 100 µL in this solution, respectively. Figure 1 (b) and (c) shows the glassy nature of the PCL coating. The relative density of these β-TCP samples were 58.63 ± 0.47 %. These β-TCP samples were sintered at 900 °C for 1 h to obtain a relatively low density samples. Presence of porosity in tissue engineering scaffolds is beneficial to achieve better mechanical interlocking between host tissue and implant through the ingrowth of newly formed tissue (19). 50 µL of PCL solution was placed on each surface of the sample in such a way that the solution does not overflow outside the sample edge. The PCL solution concentration, 5, 7.5 and 10 %, and the amount for coating were chosen to get a thin coating without filling all the pores. Figure 1(d) shows an AFM height image after PCL coating. This shows that we were able to keep the rough surface morphology with the presence of many pores even after the PCL coating.

Figure 1.

(a) Bare TCP, (b) TCP coated by 5% PCL, (c) TCP coated by PCL+LOV, lovastatin was dissolved in 5% PCL solution, (d) AFM height image of TCP coated by 5% PCL. Color scale from dark red to pink is 500 nm.

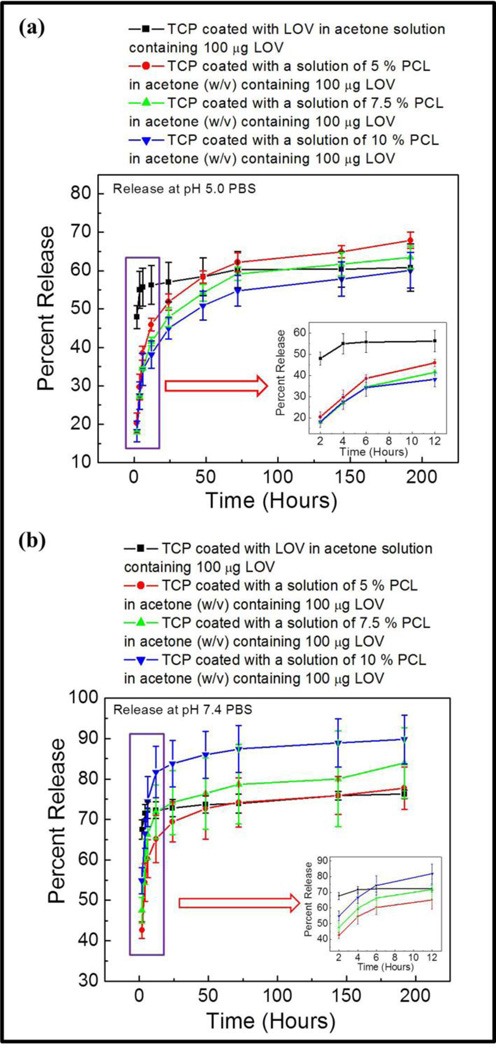

Figure 2(a) shows the percent lovastatin release at pH 5.0 acetate buffer from bare β-TCP loaded with only lovastatin, and β-TCP coated with different PCL concentration with lovastatin dissolved in that solution. All samples were loaded with same amount of lovastatin, 100 µg per sample. A burst release, around 47 %, of lovastatin was observed from bare β-TCP within 2 h leading to a plateau value after 6 h corresponding to around 55 % release. A much more sustained and controlled lovastatin release was observed from PCL coatings at pH 5 over the study period. At this pH, percent release of lovastatin was increased with decrease in PCL concentration. Lovastatin release at pH 7.4 phosphate buffer is presented in Figure 2(b). A higher burst release of lovastatin from bare β-TCP, around 66 %, was observed at pH 7.4. Similar trend in plateau value after 6 hours was also observed at pH 7.4 from bare TCP corresponding to around 72 % release. A controlled lovastatin release with a reverse trend compared to release at pH 5.0 was observed at pH 7.4. In this case, percent lovastatin release was increased with increased PCL concentration in the coating. A plateau type region was reached after 48 h of release at pH 7.4, whereas no plateau value was evident at pH 5.0. Both the initial and final percent release was higher at pH 7.4.

Figure 2.

Percent release of lovastatin with increased PCL and fixed lovastatin concentration in the coating at pH 5.0 (a), and pH 7.4 (b).

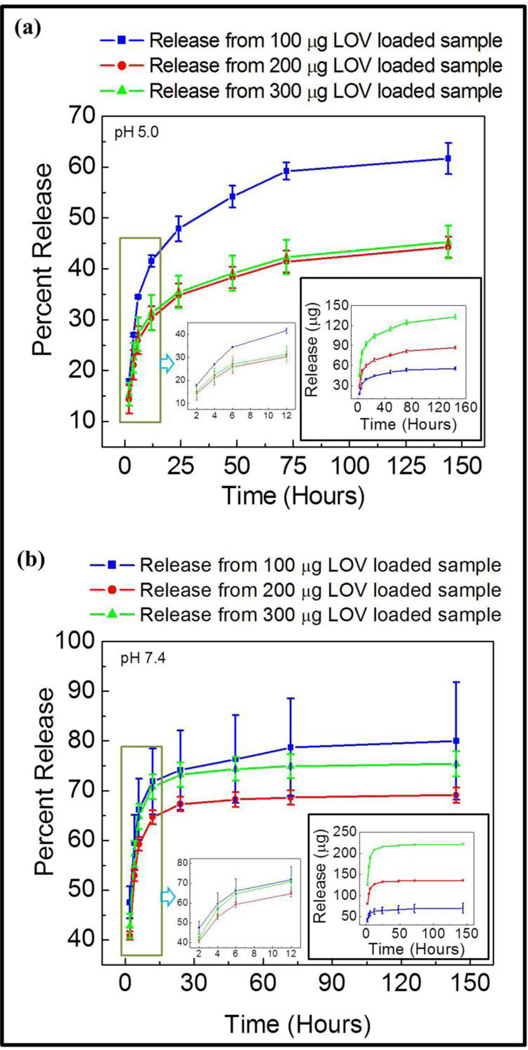

Lovastatin release behavior from a coating of fixed PCL concentration with varied drug concentration at pH 5.0 and pH 7.4 is presented in Figure 3 (a) & (b), respectively. Total amount of lovastatin release was increased at both pH 5 and pH 7.4 with increased drug concentration in the coating as expected. However, a higher initial and final lovastatin release was observed at pH 7.4 compared to pH 5 for each drug concentration. This clearly indicates the role of pH of the release media has a strong influence on lovastatin release kinetics from PCL.

Figure 3.

Percent and micro gram (inset) release of lovastatin with increased lovastatin and fixed PCL concentration in the coating at pH 5.0 (a), and pH 7.4 (b).

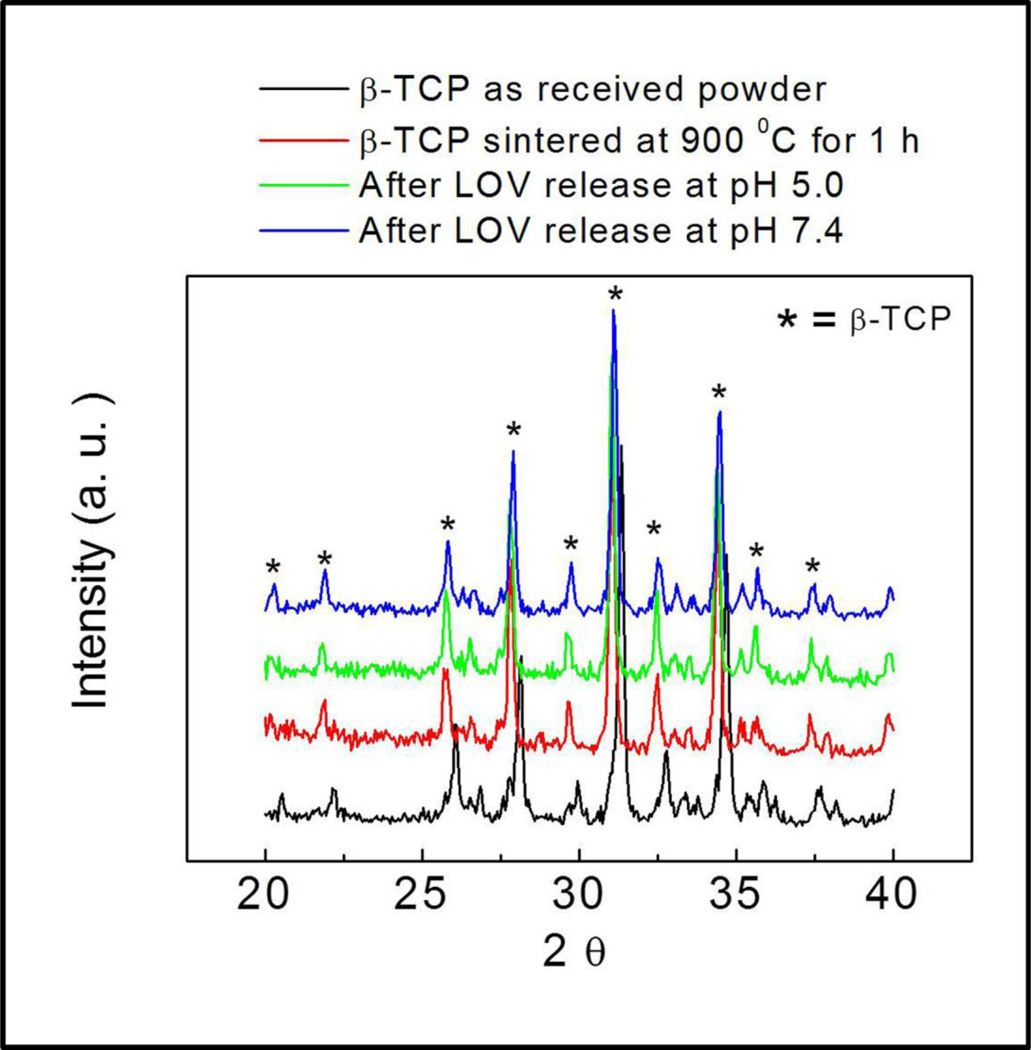

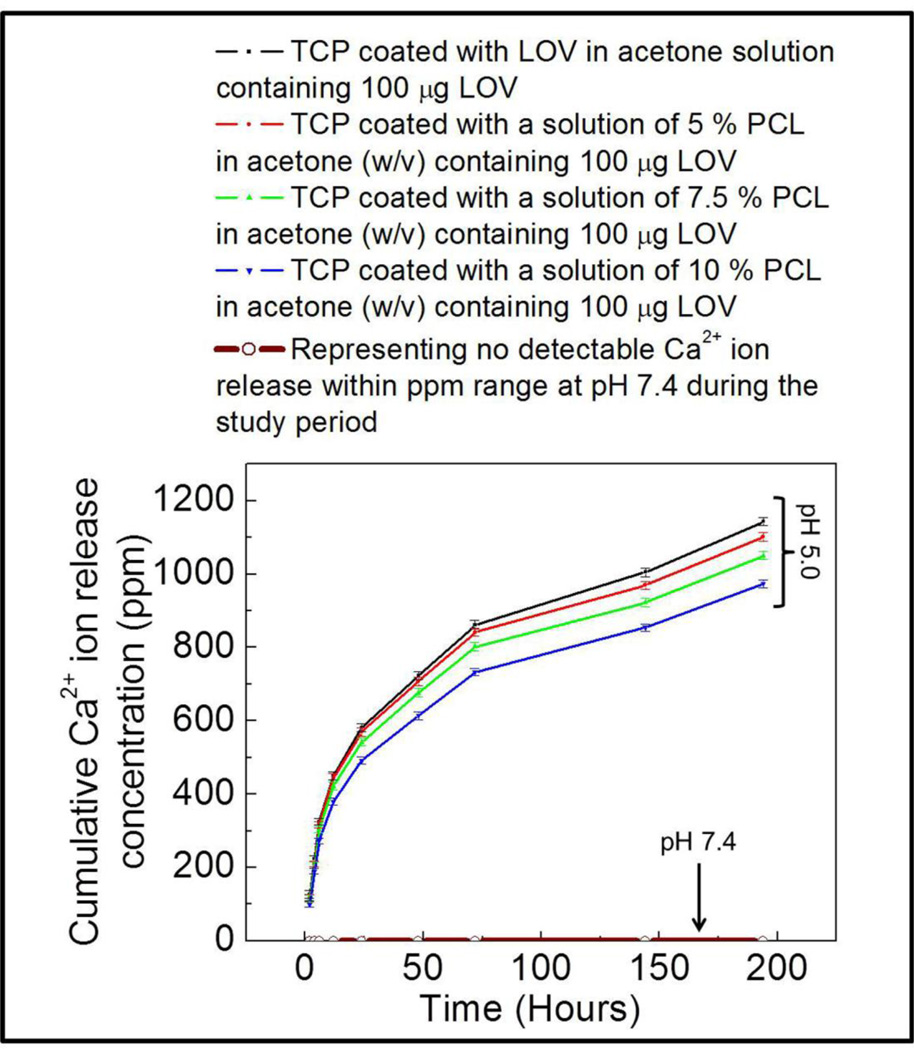

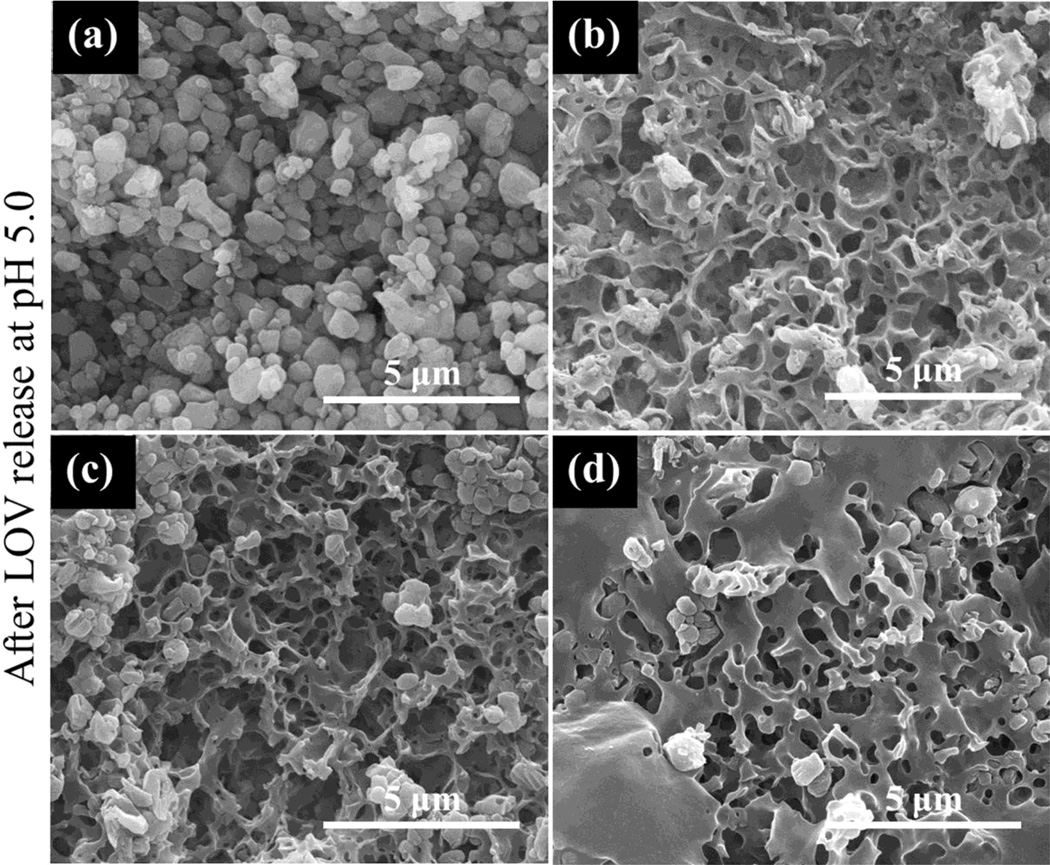

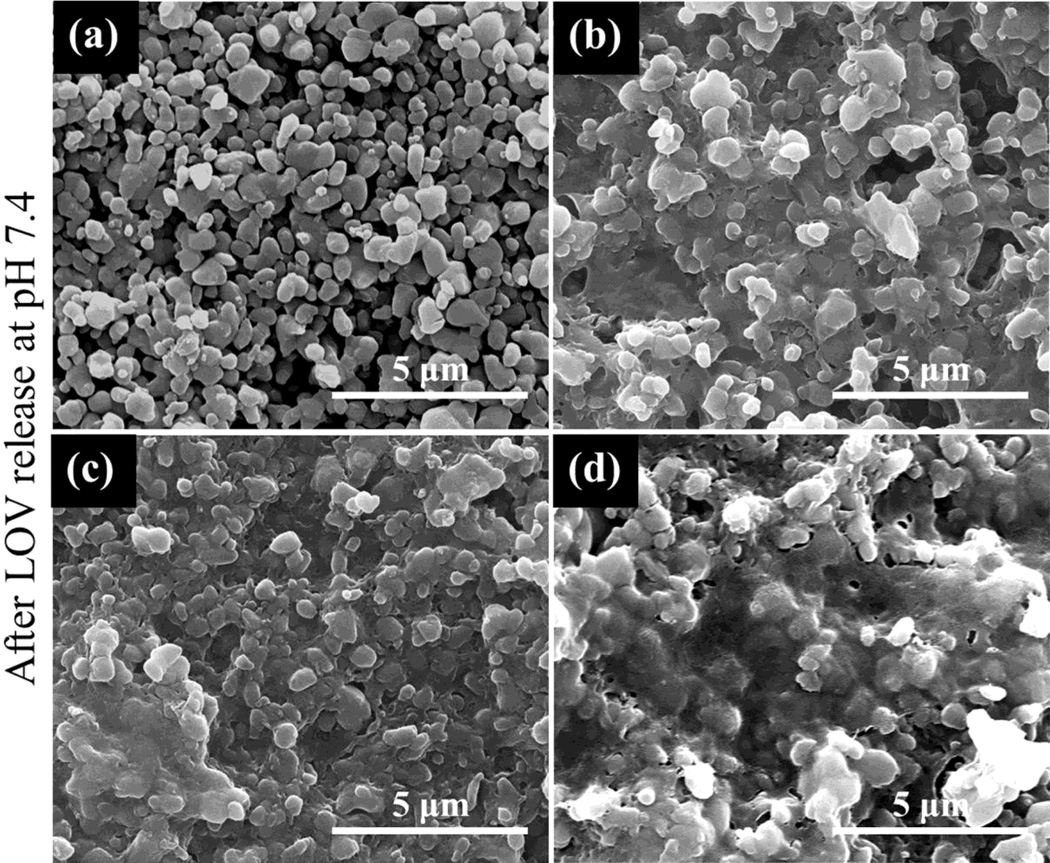

No phase change in µ-TCP was observed after LOV release at pH 5.0 and 7.4 as shown in Figure 4. Ca2+ ion concentration was also measured at each release time point along with LOV concentration measurement, and this is presented in Figure 5. A high Ca2+ ion concentration was observed at pH 5.0, whereas no Ca2+ ion release was observed at pH 7.4 within the ppm range (µg/mL) detectable limit. Surface morphology after LOV release from the bare and PCL coated TCP scaffolds at pH 5.0 and 7.4 are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively. The porous morphology of the PCL coating at pH 5.0 was caused by the degradation of PCL by acidic release media. There was no visible change in the PCL coating morphology was observed after release at pH 7.4.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the TCP samples showing no phase change after LOV release at pH 5.0 and 7.4: (a) as received β-TCP powder, (b) β-TCP sintered at 900 °C for 1 h, (c) after LOV release at pH 5.0, and (d) after LOV release at pH 7.4.

Figure 5.

Cumulative Ca2+ ion release in the release media from bare and PCL coated scaffolds at pH 5.0 and 7.4 as a function of release time. No detectable Ca2+ ion release was observed at pH 7.4 within the ppm (µg/mL) range.

Figure 6.

Surface morphology of bare TCP and PCL coated TCP scaffolds after LOV release at pH 5.0: (a) bare TCP (b) TCP coated with a 5 % PCL in acetone (w/v), (c) TCP coated with a 7.5 % PCL in acetone (w/v), and (d) TCP coated with a 10 % PCL in acetone (w/v). All these scaffolds contained 100 µg LOV before release.

Figure 7.

Surface morphology of bare TCP and PCL coated TCP scaffolds after LOV release at pH 7.4: (a) bare TCP (b) TCP coated with a 5 % PCL in acetone (w/v), (c) TCP coated with a 7.5 % PCL in acetone (w/v), and (d) TCP coated with a 10 % PCL in acetone (w/v). All these scaffolds contained 100 µg LOV before release.

4. Discussion

Drug molecules are generally attached to biomaterial surface by weak or strong electrostatic interactions [20]. These electrostatic interactions with the biomaterial surface are superseded by stronger electrostatic interactions between drug molecules and release media. A burst and uncontrolled release is the result of this phenomenon. High drug dose resulting from the burst release could be detrimental for the target tissue. Initial burst release kinetics of the applied drug followed by a plateau is very common from CaPs scaffolds [6] and coatings [21] or even only from simple drug coating on the implant surface [22]. Lovastatin release from bare TCP in this study also shows a burst release followed by a plateau region. Thus, there is a need to develop methods for controlled and sustained drug release from scaffolds and coatings for biomedical applications. Drug delivery from biodegradable polymer is very effective in controlling the burst release [14, 15, 23]. Our results show the beneficial effect of polymer coating for controlled drug delivery as compared to burst and uncontrolled uncontrolled lovastatin release from bare β-TCP.

Understanding of drug release behavior from biodegradable polymer in terms of polymer concentration, drug concentration and pH of the release media is very important for designing polymeric coating or scaffold based drug delivery devices. This study addresses lovastatin hydroxy acid (active form of lovastatin) release behavior from a hydrophobic biodegradable polymer, PCL, coating at different pH with varied lovastatin and PCL concentration. Physico-chemical nature of drug molecules such as solubility and hydrophilicity-hydrophobicity plays a vital role on release kinetics. An insoluble drug in the polymer matrix can result in inhomogeneity in the coating microstructure. On the other hand, a relatively homogeneous coating microstructure can form if drug molecules are soluble in the polymer matrix. Both lovastatin hydroxy acid and PCL are soluble in acetone. Variation in microstructure due to different processing parameters could affect the drug release kinetics even if everything else is identical [24]. In the present study, processing time and environmental condition was kept identical for all sample preparation. Thus, any variation in microstructure development due to processing parameters variation could be eliminated.

A higher lovastatin release at higher pH (7.4) is always observed whether it is from bare β-TCP or from PCL coating (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This reveals a favorable interaction between lovastatin and release media at higher pH. Polymer-drug phobicity and solubility of the polymer in the release media also need to be considered to understand the release kinetics [25]. Lower lovastatin release at lower pH (5.0) could be interpreted as more favorable interaction between lovastatin and PCL than lovastatin and release media. These favorable and unfavorable interactions between lovastatin and PCL at different pH are further confirmed by the reverse trend in the percent release at two different pH. At higher pH of the release media, gradual increase in percent release with increased PCL concentration explains that an unfavorable interaction increases with the increase in PCL concentration. On the other hand, gradual decrease in percent release with increased PCL concentration at lower pH of the release media indicates a favorable interaction between lovastatin and PCL. In one study [26], extended lovastatin release was observed when polyethylene glycol (PEG) was used as binder in pharmaceutical tablet formulation. In the same study, the authors did not observe any influence of pH of the release media on lovastatin release. This could be due to lovastatin was in its inactive lactone form and PEG binder was only 20% in the formulation. It is to be noted that the hydrophobic nature of the inactive form of lovastatin makes it insoluble in water. Thus, irrespective of the release media pH, it'll always exhibit a favorable interaction with hydrophobic polymer matrix, and an unfavorable interaction with hydrophilic polymer matrix. In another study [27], a sustained and controlled lovastatin release was observed from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles. A similar release pattern as reported in this present study was also observed at pH 7.4. In this case, the interaction between the hydrophobic inactive form of lovastatin and hydrophilic PLGA was not stable.

Although no phase change was observed in β-TCP after LOV release at pH 5.0 (acidic pH) and at pH 7.4 (basic pH) (Figure 4), a high Ca2+ ion concentration was observed at pH 5.0 (Figure 5). This is because β-TCP has a much greater solubility at acidic and neutral pH than at basic pH [28]. The porous nature of the PCL coating after LOV release at pH 5.0 (Figure 6) is an example of chemical degradation caused by the acidic release media. No such degradation of the PCL coating was observed at pH 7.4 (Figure 7). Drug release can depend on diffusion, chemical processes, and external or electronic processes [29]. Degradation of polymer also could affect the drug release kinetics [15]. Drug release kinetics is primarily a diffusion dominated process, because degradation is always slower than the diffusion. Lovastatin release from PCL increased linearly only for initial few hours, up to 6 h. Thus, initial lovastatin release is probably diffusion dominated. After that, other factors such as polymer-drug interaction, diffusion with degradation start affecting the release kinetics. Our results also show that diffusion dominated release played the key role over other release processes. Lovastatin release was always higher at pH 7.4 even though high solubility of β-TCP and PCL degradation were observed at pH 5.0 compared to no detectable solubility and visible PCL degradation at pH 7.4. We could have seen a higher lovastatin release at pH 5.0 than at pH 7.4, if other processes had any dominant role over diffusion. However, drug diffusion from the polymer coating was controlled by the interaction between drug molecules and the polymer matrix.

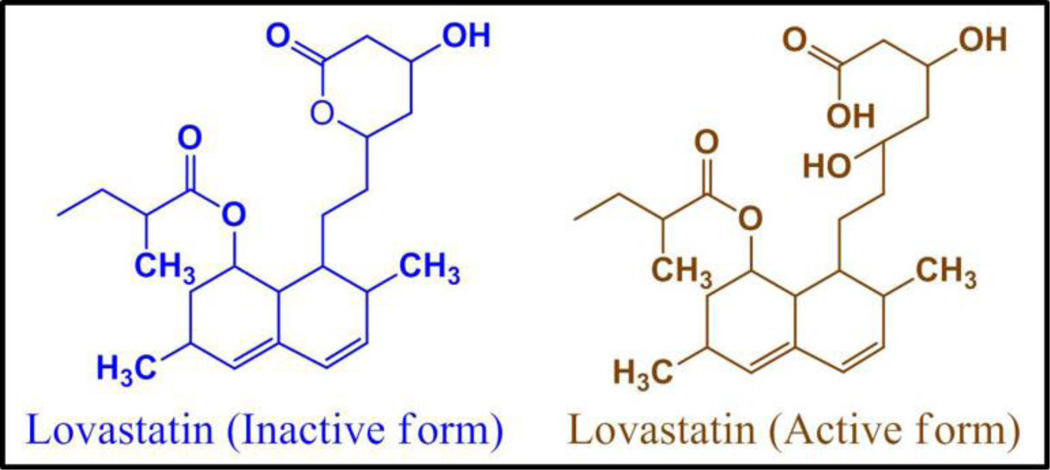

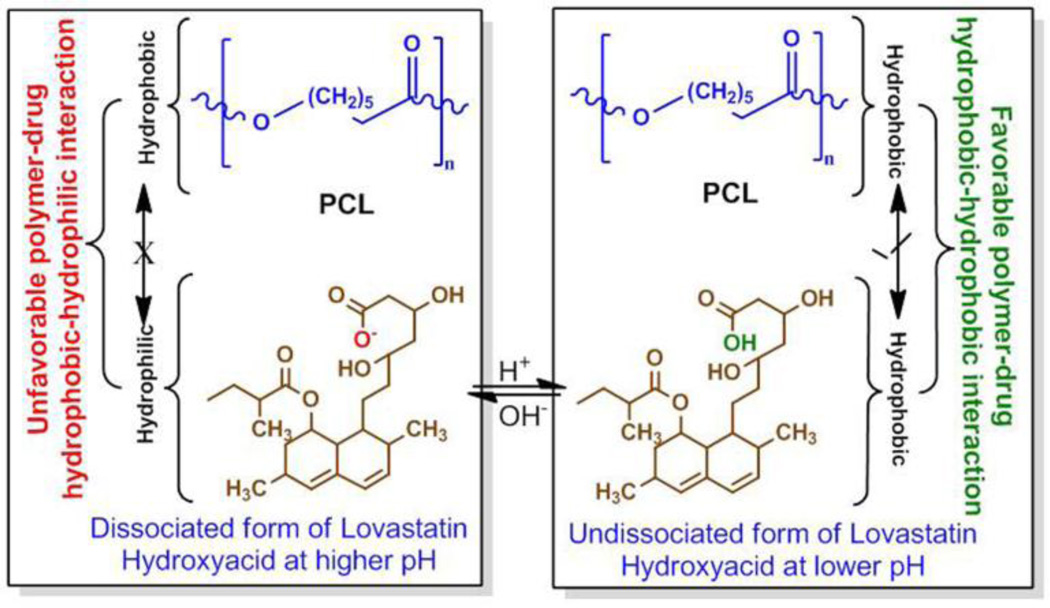

Favorable and unfavorable interactions between lovastatin and PCL at different pH can be explained from their chemical structures. Inactive (lactone form) and active (hydroxyl acid form) form of lovastatin is presented in Figure 8. Lovastatin is present in its active hydroxyl acid form in the PCL coating. At higher pH, lovastatin dissociates one proton. This dissociated form of lovastatin is more hydrophilic in nature than its undissociated form. This hydrophilicity of deprotonated lovastatin and hydrophobicity of PCL is the reason for the unfavorable interaction between them. At fixed lovastatin concentration, the hydrophilic-hydrophobic interaction increases with the increase in PCL concentration. Thus, the higher release at higher pH with increased PCL concentration in the coating is due to increased unfavorable hydrophilic-hydrophobic interaction [25] between deprotonated lovastatin and PCL, which makes lovastatin more stable in the release media. In line with our findings, a similar increase in tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) release, an antibiotic drug, with increased PCL concentration in the coating was also reported at pH 7.4 [14]. The undissociated form of lovastatin hydroxyl acid is more hydrophobic compared to the dissociated form. Thus, a favorable hydrophobic-hydrophobic interaction resulting stabilization of the drug molecules in the delivery matrix is the reason for lower release at lower pH, and a decrease in release with the increase in PCL concentration. Figure 9 shows the schematic of this hydrophilic-hydrophilic and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 8.

Inactive lactone and active hydroxyl acid forms of lovastatin.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the hydrophilic-hydrophobic, and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions between lovastatin-PCL in presence of relatively acidic and basic release media.

The solubility of the polymer in the release media also affects the drug release kinetics. Deviations in drug release and release variability are much larger in soluble polymeric coating compared to insoluble polymeric coating with identical drug loading and coating thickness [25]. As it is evident from this study, the release of lovastatin from this PCL coated β-TCP system is primarily diffusion dominated. Nevertheless, bulk dissolution and polymer degradation is also contributing to the total release towards some extent. The drug diffusion process is controlled by the complex interactions between drug-polymer and drug-release media. Commonly used release kinetics models do not fit well to this system due to the complex nature of the release process. Considering all these factors and some other factors (microstrueture and polymer solubility in the solvent), Saylor et al. [25] have already proposed a complex equation based on mathematical modeling. Our experimental results fit well with the models developed by them. This study shows that drug-polymer hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions between lovastatin and PCL are the dominant factors that control lovastatin release from PCL coating. Therefore, knowledge of the physico-chemical properties of the drug and polymer, and drug-polymer interactions depending of their hyrophobicity and hydrophilicity will lead us to design polymeric drug vehicles/devices with tailorable properties for the specific need.

4. Conclusion

A controlled and steady lovastatin release was observed from PCL coating as compared to a burst and uncontrolled release from bare TCP. Increased initial and final lovastatin release was observed at higher pH than lower pH. As expected, increased lovastatin release was observed with increasing concentration. At pH 5.0 Lovastatin release was decreased with increasing PCL concentration, whereas release was increased with increasing PCL concentration at pH 7.4. Lovastatin release from PCL matrix was dominated by drug-polymer hydrophilic-hydrophobic and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions depending on the pH of the release media. Based on our results, we propose a mechanistic understanding of lovastatin release behavior from PCL coating on TCP. This mechanistic approach can be extended to other drug and polymeric systems. Thus, the understanding of the chemistry of lovastatin release from PCL coating would facilitate us design biomaterials for controlled local drug delivery from polymeric coatings or scaffolds for tissue engineering applications.

Highlights.

Lovastatin release chemistry from PCL coated β-TCP was examined.

Incorporation of lovastatin into PCL coating contributed to a controlled release.

PCL amount in the coating and pH of the release media affected the release kinetics.

Drug-polymer Hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity were the dominant factors.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Nehal Abu-Lail and her group from Gene and Linda Voiland School of Chemical Engineering and Bioengineering, Washington State University for their assistance with Atomic Force Microscope.

Funding Source

National Institute of Health (NIH), NIBIB under the Grant No. NIH-R01-EB-007351.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, Oliyai R, Oh D, Jarvinen T, Savolainen J. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(3):255–270. doi: 10.1038/nrd2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayukawa Y, Yasukawa E, Moriyama Y, Ogino Y, Wada H, Atsuta I, Koyano K. Local application of statin promotes bone repair through the suppression of osteoclasts and the enhancement of osteoblasts at bone-healing sites in rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demierre M-F, Higgins PDR, Gruber SB, Hawk E, Lippman SM. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(12):930–942. doi: 10.1038/nrc1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo J-T, Nakagawa H, Krecic AM, Nagai K, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM, Stern PH. Inhibitory effects of mevastatin and a geranylgeranyl transferase I inhibitor (GGTI-2166) on mononuclear osteoclast formation induced by receptor activator of NFKB ligand (RANKL) or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(l):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mundy G, Garrett R, Harris S, Chan J, Chen D, Rossini G, Boyce B, Zhao M, Gutierrez G. Stimulation of bone formation in vitro and in rodents by statins. Science. 1999;286(5446):1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyan M, Miyahara T, Noritake K, Hao J, Rodriguez R, Kuroda S, Kasugai S. Molecular and tissue responses in the healing of rat calvarial defects after local application of simvastatin combined with alpha tricalcium phosphate. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomaterials. 2010;93(l):65–73. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda T, Matsunuma A, Kawane T, Horiuchi N. Simvastatin Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation and Mineralization in MC3T3-E1 Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280(3):874–877. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrett Ir, Gutierrez Ge, Rossini G, Nyman J, McCluskey B, Flores A, Mundy Gr. Locally delivered lovastatin nanoparticles enhance fracture healing in rats. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(10):1351–1357. doi: 10.1002/jor.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Osteoporosis Foundation. http://www.nof.org.

- 10.Chen P-Y, Sun J-S, Tsuang Y-H, Chen M-H, Weng P-W, Lin F-H. Simvastatin promotes osteoblast viability and differentiation via Ras/Smad/Erk/BMP-2 signaling pathway. Nutr Res. 2010;30(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong RWK, Rabie ABM. Statin collagen grafts used to repair defects in the parietal bone of rabbits. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(4):244–248. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriyama Y, Ayukawa Y, Ogino Y, Atsuta I, Todo M, Takao Y, Koyano K. Local application of fluvastatin improves peri-implant bone quantity and mechanical properties: A rodent study. Acta Biomater. 2010;6(4):1610–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue W, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Polycaprolactone coated porous tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for controlled release of protein for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2009;91(2):831–838. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HW, Knowles JC, Kim HE. Hydroxyapatite/poly (-caprolactone) composite coatings on hydroxyapatite porous bone scaffold for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2004;25(7–8):1279–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bose S, Tarafder S. Calcium phosphate ceramic systems in growth factor and drug delivery for bone tissue engineering: A review. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8:1401–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombes AGA, Rizzi SC, Williamson M, Barralet JE, Downes S, Wallace WA. Precipitation casting of polycaprolactone for applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2004;25(2):315–325. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng KW, Hutmacher DW, Schantz J-T, Ng CS, Too H-P, Lim TC, Phan TT, Teoh SH. Evaluation of Ultra-Thin Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Films for Tissue-Engineered Skin. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(4):441–455. doi: 10.1089/10763270152436490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattanavee W, Suwantong O, Puthong S, Bunaprasert T, Hoven VP, Supaphol P. Immobilization of Biomolecules on the Surface of Electrospun Polycaprolactone Fibrous Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;l(5):1076–1085. doi: 10.1021/am900048t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarafder S, Balla VK, Davies NM, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Microwave-sintered 3D printed tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012 doi: 10.1002/term.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarafder S, Banerjee S, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Electrically Polarized Biphasic Calcium Phosphates: Adsorption and Release of Bovine Serum Albumin. Langmuir. 2010;26(22):16625–16629. doi: 10.1021/la101851f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radin S, Campbell JT, Ducheyne P, Cuckler JM. Calcium phosphate ceramic coatings as carriers of vancomycin. Biomaterials. 1997;18(ll):777–782. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshinari M, Matsuzaka K, Hashimoto S, Ishihara K, Inoue T, Oda Y, Ide T, Tanaka T. Controlled release of simvastatin acid using cyclodextrin inclusion system. Dent Mater J. 2007;26(3):451–456. doi: 10.4012/dmj.26.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H-W, Knowles JC, Kim H-E. Hydroxyapatite porous scaffold engineered with biological polymer hybrid coating for antibiotic Vancomycin release. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2005;16(3):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-6679-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saylor DM, Kim C-S, Patwardhan DV, Warren JA. Diffuse-interface theory for structure formation and release behavior in controlled drug release systems. Acta Biomater. 2007;3(6):851–864. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saylor DM, Kim C, Patwardhan DV, Warren JA. Modeling micro structure development and release kinetics in controlled drug release coatings. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98(l):169–186. doi: 10.1002/jps.21416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochoa L, Igartua M, Hernández RM, Gascón AR, Solinis MA, Pedraz JL. Novel extended-release formulation of lovastatin by one-step melt granulation: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;77(2):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho M-H, Chiang C-P, Liu Y-F, Kuo MY-P, Lin S-K, Lai J-Y, Lee B-S. Highly efficient release of lovastatin from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles enhances bone repair in rats. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(10):1504–1510. doi: 10.1002/jor.21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez E, Gil FJ, Ginebra MP, Driessens FCM, Planell JA, Best SM. Calcium phosphate bone cements for clinical applications Part 1: Solution chemistry. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 1999;10:169–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1008937507714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginebra M-P, Traykova T, Planell JA. Calcium phosphate cements: Competitive drug carriers for the musculo skeletal system? Biomaterials. 2006;27(10):2171–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]