Abstract

Recognising an object involves more than just visual analyses; its meaning must also be decoded. Extensive research has shown that processing the visual properties of objects relies on a hierarchically organised stream in ventral occipitotemporal cortex, with increasingly more complex visual features being coded from posterior to anterior sites culminating in the perirhinal cortex (PRC) in the anteromedial temporal lobe (aMTL). The neurobiological principles of the conceptual analysis of objects remain more controversial. Much research has focussed on two neural regions - the fusiform gyrus and aMTL, both of which show semantic category differences, but of different types. fMRI studies show category differentiation in the fusiform gyrus, based on clusters of semantically similar objects, whereas category-specific deficits, specifically for living things, are associated with damage to the aMTL. These category-specific deficits for living things have been attributed to problems in differentiating between highly similar objects, a process which involves the PRC. To determine whether the PRC and the fusiform gyri contribute to different aspects of an object’s meaning, with differentiation between confusable objects in the PRC and categorisation based on object similarity in the fusiform, we carried out an fMRI study of object processing based on a feature-based model which characterises the degree of semantic similarity and difference between objects and object categories. Participants saw 388 objects for which feature statistic information was available, and named the objects at the basic-level while undergoing fMRI scanning. After controlling for the effects of visual information, we found that feature statistics that capture similarity between objects formed category clusters in fusiform gyri, such that objects with many shared features (typical of living things) were associated with activity in the lateral fusiform gyri while objects with fewer shared features (typical of nonliving things) were associated with activity in the medial fusiform gyri. Significantly, a feature statistic reflecting differentiation between highly similar objects, enabling object-specific representations, was associated with bilateral PRC activity. These results confirm that the statistical characteristics of conceptual object features are coded in the ventral stream, supporting a conceptual feature-based hierarchy, and integrating disparate findings of category responses in fusiform gyri and category deficits in aMTL into a unifying neurocognitive framework.

Introduction

Recognising an object involves not only an analysis of its visual properties, but also the computation of its meaning. The neural system supporting visual analysis has been characterised as a hierarchical neurobiological system of increasing feature complexity in occipitotemporal cortex. Simple visual features are integrated into more complex feature combinations from visual cortex to anterior temporal regions along ventral occipitotemporal cortex (Tanaka, 1996; Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982). At the apex of this stream, perirhinal cortex (PRC) is claimed to perform the most complex visual feature integrations required to discriminate between highly similar objects (Bussey, Saksida, & Murray, 2002; Murray & Bussey, 1999; Murray, Bussey, & Saksida, 2007).

The neurobiological principles of the conceptual analysis of objects remain more controversial, with studies primarily focussing on category structure (Chao, Haxby, & Martin, 1999; Mahon & Caramazza, 2009; Martin, 2007; McRae, de Sa, & Seidenberg, 1997; Tyler & Moss, 2001; Warrington & McCarthy, 1983; Warrington & Shallice, 1984) and its organising principles. These are claimed to include domain or category membership or different property types which are shared amongst members of a category (e.g. visual, functional, and motor properties). Object categories have been associated with two neural regions in the ventral stream: the fusiform gyrus and the antero-medial temporal cortex (Chao, et al., 1999; Humphreys & Forde, 2001; Martin, 2007; Moss, Rodd, Stamatakis, Bright, & Tyler, 2005; Tyler, et al., 2004; Warrington & Shallice, 1984). Evidence for category differentiation in the fusiform gyrus comes from fMRI studies with healthy volunteers in which different parts of the fusiform preferentially respond to different object categories such as tools and animals (Chao, et al., 1999) while neighbouring regions of the lateral occipital complex (LOC) show little category selectivity (Op de Beeck, Torfs, & Wagemans, 2008).

Category effects in the ventral stream have also been observed in studies of neuropsychological patients who show category-selective deficits. The most frequently reported findings are for category-specific deficits for living things in response to damage in anteromedial temporal lobe (aMTL) (Humphreys & Forde, 2001; Moss, et al., 2005; Tyler, et al., 2004; Warrington & Shallice, 1984). In contrast, patients with antero-lateral temporal lobe damage have a generalised semantic impairment and no category-specific impairment (Moss, et al., 2005; Noppeney, et al., 2007; Rogers, et al., 2006). This distinction between antero-medial and antero-lateral involvement has been further supported by neuroimaging studies with healthy volunteers which show that living things preferentially engage the aMTL (Moss, et al., 2005; Taylor, Moss, Stamatakis, & Tyler, 2006; Tyler, et al., 2004).

Category-specific deficits for living things following damage to the anteromedial temporal cortex have been attributed to patients’ difficulties in differentiating between highly similar objects (Moss, et al., 2005; Taylor, et al., 2006; Tyler, et al., 2004). While patients with aMTL damage have no difficulty in determining the category of an object, they are exceptionally poor at differentiating between similar objects, and this pattern is most marked for living things, especially animals (Moss, et al., 2005; Moss, Tyler, & Jennings, 1997; Tyler, et al., 2004) which are amongst the most highly confusable objects according to property norm data (Keil, 1986; Malt & Smith, 1984; McRae, et al., 1997; Randall, Moss, Rodd, Greer, & Tyler, 2004). In patients with category-specific deficits, aMTL damage tends to be extensive, but one region within it – the PRC – may be the primary contributor to the deficit (Kivisaari, Tyler, Monsch, & Taylor, 2012; Tyler, et al., 2004) since this region provides the neural infrastructure for complex feature integration which enables the fine-grained differentiation required for distinguishing between highly similar objects (Barense, Henson, & Graham, 2011; Moss, et al., 2005; Tyler, et al., 2004). Other findings support this suggestion; PRC lesions in non–human primates are associated with deficits in the ability to differentiate between highly ambiguous objects (Bussey, et al., 2002; Saksida, Bussey, Buckmaster, & Murray, 2007) and patients with aMTL damage which includes the PRC have difficulty in complex feature ambiguity tasks (Barense, et al., 2005; Barense, Gaffan, & Graham, 2007).

To determine whether the PRC and the fusiform gyri contribute to different aspects of an object’s meaning with differentiation between confusable objects in the PRC and category differentiation in the fusiform, we carried out an fMRI study of object processing based on a feature-based model which characterises the degree of semantic similarity and difference between objects and object categories. Feature-based models assume that conceptual representations are componential in nature: that they are made up of smaller elements of meaning, referred to as features, properties or attributes. They account for categorisation on the assumption that semantic categories are based on feature similarity, although models differ with respect to the nature of the attributes considered and the similarity computations they hypothesise (Smith & Medin, 1981). Componentiality, while not universally accepted, is now widely assumed in cognitive psychology (Cree & McRae, 2003; Gotts & Plaut, 2004; McRae, et al., 1997; Mirman & Magnuson, 2008; Randall, et al., 2004), and accounts for behavioural aspects of processing the semantics of objects (McRae, et al., 1997; Pexman, Holyk, & Monfils, 2003; Randall, et al., 2004; Taylor, Devereux, Acres, Randall, & Tyler, 2012). This type of model also has the potential to capture the characteristics that distinguish objects from each other and thus enable individuation between similar objects. While features which are shared by many objects provide the basis for categorisation, those which are distinctive of a specific object enable similar objects to be differentiated from each other (Cree & McRae, 2003; McRae & Cree, 2002; Taylor, et al., 2012; Taylor, Salamoura, Randall, Moss, & Tyler, 2008; Tyler & Moss, 2001).

The model used in the present study was based on 2,526 features derived from a large-scale norming study of 541 concepts (McRae, Cree, Seidenberg, & McNorgan, 2005; Taylor, et al., 2012). In this study participants generated verbal features lists for each concept. While the listed features (e.g. has stripes) are not intended to literally reflect all real features of a particular object, the statistical regularities of these features do reflect systematic statistical regularities we experience in the world which capture the content and structure of conceptual representations, provide a basis for categorisation, and predict responses to semantic tasks using both words (Grondin, Lupker, & McRae, 2009; McRae, et al., 1997; Randall, et al., 2004) and pictures (Clarke, Taylor, Devereux, Randall, & Tyler, 2013; Taylor, et al., 2012, experiments 1 and 2). Two key aspects of conceptual representation have been tested and validated in these cognitive studies and form the basis of the current study. One important variable is the extent to which an object’s features are shared by many (e.g. many animals have fur) or few concepts (e.g. few animals have stripes). The property norm statistics show that living things (e.g. animals) have many shared and few distinctive features, while nonliving things (e.g. tools) have fewer shared and relatively more distinctive features (Cree & McRae, 2003; Tyler & Moss, 2001). The issue is whether sharedness will be associated with activity in the fusiform, and if so, whether these property statistics will be associated with differentiation within the fusiform. Specifically, will the differential effects of sharedness overlap with the medial-lateral distinction in the fusiform such that the effects of greater sharedness will overlap with the lateral fusiform, known to be associated with animals (Chao, et al., 1999), and effects of fewer shared features will overlap with tool-associated regions of the medial fusiform (Chao, et al., 1999)? That is, does the feature statistic variable of Sharedness explain fusiform gyrus activity as well as the living/nonliving variable?

A second feature statistic variable is that of correlational strength or feature co-occurrence, where highly correlated features (e.g. has eyes and has ears) co-occur frequently and mutually co-activate, facilitating feature integration (McRae, et al., 1997; Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson, & Boyes-Braem, 1976). Property norm statistics show that living things have more weakly correlated distinctive features compared with nonliving things (Randall, et al., 2004; Taylor, et al., 2008), making them more difficult to differentiate from other category members. As a consequence, living things are disadvantaged relative to nonliving things on those tasks which require differentiation between similar objects. One such task is basic-level identification which requires differentiating between similar objects by integrating a concept’s distinctive features with its shared features. For example, a basic-level naming response cannot be made on the basis of individual features such as the shared features has legs (dog? etc.) or lives in zoos (elephant?), or the distinctive feature has stripes (shirt?). Instead, the individual shared and distinctive features must be integrated together (has legs + lives in zoos + has stripes) to know that the concept is, for example, a tiger. This process is facilitated by the correlational strength of a concept’s distinctive features: concepts with weakly correlated distinctive features, which are more difficult to integrate with the other object features, place greater demands on the complex feature integration computations required for basic-level identification. In contrast, concepts with relatively highly correlated distinctive features are identified at the basic level more quickly than concepts with weakly correlated distinctive features (Randall, et al., 2004; Taylor, et al., 2012). The issue is whether the PRC, which is claimed to integrate the most complex feature conjunctions, will be preferentially engaged by these processes.

In the present fMRI study we used a basic-level naming task because it engages the entire ventral stream (Tyler, et al., 2004) and therefore allows us to determine whether regions within the stream are involved in processing different aspects of an object’s meaning. To determine whether feature statistic variables account for activity within different regions of the stream, we correlated activity with the two conceptual structure variables Sharedness and Correlation × Distinctiveness (see Task Design and Materials) after visual effects had been accounted for. We predicted that these two variables would differentiate between neural regions where activity is driven by (a) similarity of conceptual structure reflecting category structure (i.e. the relative amount of shared features within a concept) and (b) differentiation between similar concepts (Correlation × Distinctiveness, i.e. the relative extent to which the distinctive features critical to basic-level differentiation are correlated with other features in the concept).

Methods

Participants

15 healthy, right-handed, native British English speakers participated in the fMRI study (9 males; mean age 24 ± 5 years). The major exclusion criteria were bilingualism, left-handedness, MR contraindications, neurological, psychiatric or hormonal disorders, dyslexia, and colour-blindness. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, gave informed consent and they were paid for their participation. The study was approved by the East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee.

Task Design and Materials

This fMRI study measured the influence of feature statistic variables on blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) activity associated with basic-level picture naming, while controlling for visual variables. We selected all picturable concepts (n = 388) from an anglicised version (Taylor, et al., 2012) of the McRae et al. (2005) property norm set. The pictures had high exemplarity (i.e. ratings on a 7-point Likert scale, which reflect the goodness with which the picture represented the written concept word, with 7 reflecting a perfect representation). An independent group of 17 healthy individuals, gave a mean rating (±standard deviation) of 5.11 (±0.88), ensuring that the object pictures are representative of the concept. The mean naming and concept agreement for the picture set was 76% and 82% based on a further independent sample of 20 healthy participants. The feature statistic variables were based on standard measures of ‘feature distinctiveness’ (i.e. 1 / [number of concepts the feature occurs in]) and the correlational strength of features (McRae, et al., 1997; Randall, et al., 2004; Rosch, et al., 1976; Taylor, et al., 2012; Tyler & Moss, 2001; Vigliocco, Vinson, Lewis, & Garrett, 2004) calculated based on the entire set of 517 anglicised feature norm concepts (McRae et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2012). ‘Feature distinctiveness’ has higher values for more distinctive features such as has stripes but lower values for shared features such as has fur. We are interested in these shared features, since they provide the basis for categorisation.

From these two standardly used measures, we calculated two feature statistic indices. The first measure, Sharedness, is a measure of the degree of sharedness of the features in a concept (i.e. how often a concept’s features occur in other concepts). For each concept, Sharedness is defined as 1 minus the square-root of the mean distinctiveness of the concepts’ features (the square-root transformation was applied to reduce the skew of the distribution). Sharedness has high values for concepts with proportionately more shared features (e.g. animals) and low values for concepts with proportionately more distinctive features (e.g. tools; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all stimuli and separately for living and nonliving objects: key feature statistic variables (C×D = Correlation × Distinctiveness; NOF = number of features; NODF = number of distinctive features), objective visual complexity (size of JPEG files), naming & concept agreement and naming latency for correct trials (reaction time / RT).

| All | Living | Nonliving | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | |

| Sharedness | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.14 |

| C×D | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.84 |

| Correlational strength * | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.07 |

| NOF | 12.6 | 3.3 | 13.1 | 3.5 | 12.2 | 3.2 |

| NODF | 3.9 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 2.7 |

| Visual complexity (JPEG filesize) |

10.5 | 0.6 | 10.7 | 0.5 | 10.4 | 0.6 |

| Naming agreement (%) | 76 | 28 | 71 | 32 | 79 | 25 |

| Concept agreement (%) | 82 | 25 | 75 | 30 | 87 | 20 |

| RT (correct name, msec) | 965 | 77 | 990 | 82 | 951 | 75 |

mean correlation of shared features within concept

Second, we calculated Correlation × Distinctiveness as the slope of the regression of correlational strength on distinctiveness values over all features in the concept, excluding highly distinctive features which occur in only one or two concepts since their correlational strength values may be spurious (Cree, McNorgan, & McRae, 2006; Taylor, et al., 2012; Taylor, et al., 2008). This measure represents the relative correlational strength of shared vs. distinctive features within a concept. Thus, concepts with low or negative Correlation × Distinctiveness values have relatively weakly correlated distinctive compared to shared features, generating greater demands on complex conceptual integration processes which bind distinctive with shared features to enable basic-level identification (see Table 1).

We also constructed variables to represent the visual information present in the pictures using Gabor-filtered images to capture the spatial position and orientation of the objects. Related Gabor filter models have been used to model perceptual processing in the visual system (Kay, Naselaris, Prenger, & Gallant, 2008; Naselaris, Prenger, Kay, Oliver, & Gallant, 2009; Nishimoto, et al., 2011). Grey-scale versions of the images were reduced to 153×153 pixels before applying Gabor filters with 4 orientations (0, 45, 90, 130 degrees) and 5 spatial frequencies (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 Hz [cycles / image]). Next, the set of 388 Gabor-filtered pictures were vectorised, and the 23,409 pixel by 388 picture matrix was entered into a principal components analysis (PCA) using the Matlab function ‘princomp’ (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Each resulting component described part of the variance in pixel intensity across the set of pictures, with the first component describing the strongest common influence on variance (i.e. overall intensity) and subsequent components describing progressively more subtle components of the variance (e.g. difference in intensity between the top and bottom of the image, centre and surround etc.). The first eight components were selected, according to the Scree test, and together explained 60% of the variance in image intensity. The loadings of these eight components on the 388 images were used to model the visual properties of the pictures.

All pictures, on a white background, were resized to fit comfortably on a computer screen with the longest axis spanning maximally 750 pixels horizontally or 550 pixels vertically (maximum visual angle 12.2° horizontally or 9.0° vertically), and were saved as JPEG images using identical compression settings. In addition to these 388 objects, the stimuli in the fMRI study included fixation crosses (n = 50) and phase-scrambled images of target stimuli (n = 54; scrambled using the Fourier method in Matlab) as low level visual baselines.

The items were presented in the same pseudorandomised order for each participant. The pseudorandomisation ensured that no more than two items from the same semantic category (eg, animal, furniture, vegetable) or beginning with the same phoneme followed one another. The pseudorandomisation of pictures with fixation and scrambled images ensured a jittered, geometric distribution of stimulus onset asynchronies for the picture stimuli, which optimises detection of BOLD activity.

fMRI procedure

Pictures and baseline stimuli were pseudorandomised and presented in two blocks of approximately equal length. Each stimulus was displayed in the centre of a projection screen in the scanner for 2000 ms followed by an inter-trial interval of 1100 ms. Participants were instructed to name aloud each picture as quickly and accurately as possible, to respond to phase-scrambled images by saying “blur” aloud, and to fixate on a fixation cross without responding. E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, PA) controlled presentation and timing of stimuli. Participants’ spoken responses were collected during scanning using an OptiMRI noise-cancelling microphone system (Optoacoustics Ltd., Moshav Mazoe, Israel). Stutters and no responses were scored as incorrect. Moreover, only object names which exactly corresponded to the concept name in the feature norm study (McRae et al., 2005) were scored as correct and thus included in the fMRI analyses to ensure that the corresponding feature statistic data were valid measures of the processed concept (e.g. while both “bread” and “loaf” could describe a given object, they may be associated with different non-perceptual and perceptual features).

Participants’ response latencies were calculated using in-house software on the voice recordings made during the scan. Continuous scanner recordings were filtered to suppress frequencies over 700 Hz using a Chebyshev type I filter and split into segments containing naming responses to individual items. Naming onsets were determined relative to picture onset using custom software by finding the first time-point where both a) the root-mean square (RMS) power exceeded 5 standard deviations above a pre-object baseline period, and b) this RMS power level was exceeded for at least 40 ms. Any naming latencies less than 500 ms were manually verified and corrected if necessary. To reduce the influence of outlying response latencies, we inverse-transformed the individual response times (Ratcliff, 1993) then retransformed them after averaging for each participant to give the harmonic mean (msec).

Image Acquisition

Scanning was conducted on a 3 T Siemens Tim Trio system at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England. Continuous functional scans were collected using gradient echo echo-planar imaging with 32 slices, 3 mm isotropic voxel dimensions, TR = 2 s, TE = 30 ms, FOV = 192 × 192 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, flip angle = 78 degrees. T1-weighted anatomical MPRAGE scans were acquired with TR = 2250 ms, TE = 3 ms, TI = 900 ms, FOV= 256 mm × 240 mm × 160 mm, matrix size = 256 × 240 × 160.

Imaging Analyses

fMRI data were preprocessed and analysed with SPM5 software (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm5/) implemented in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Preprocessing comprised slice time correction, within-subject realignment (motion correction), unified spatial normalisation and spatial smoothing with an 8 mm FWHM Gaussian smoothing kernel. Low frequency noise was removed using a high-pass filter with a period of 128 s in the SPM general linear model (GLM).

Each participant’s data were analysed with the GLM using the canonical haemodynamic response function. The correctly named pictures, incorrectly named pictures, and two baseline conditions were modelled as separate regressors. We also modelled the visual and feature statistic variables as parametric modulators of the regressor for correctly named pictures: first the eight PCA components characterising the Gabor-filtered images, then Sharedness and finally Correlation × Distinctiveness. Each modulator was orthogonalised with respect to previous modulators, ensuring that the effects of the feature statistic variables were not confounded with the visual variables. We confirmed that the Sharedness and CxD variables were not correlated with each other (r = .06, p > .05), and that there were no significant correlations between any of the eight Gabor PCA variables and either Sharedness or CxD (max. r < .14, all FWE-p > .05). The model also included the six movement parameters produced by realignment (above) as nuisance variables.

The GLM in SPM includes implicit masking, which by default excludes voxels with signal below 80% of the mean signal over all voxels in the brain. This heuristic is used to avoid including brain regions with low BOLD signal due to variations in magnetic susceptibility, such as the anterior temporal regions under investigation. Because this heuristic approach may exclude voxels with low but reliable BOLD signal, we lowered the implicit masking threshold to 10% and then defined reliable voxels using a more specific measure of temporal signal-to-noise ratio (TSNR). We calculated TSNR maps for each subject by dividing the mean functional image intensity over time at each voxel by its standard deviation. We then calculated a group-average TSNR map and defined reliable voxels as those with mean TSNR > 40 (Murphy, Bodurka, & Bandettini, 2007). The group-average TSNR map indicated adequate reliability of signal in the anteromedial temporal lobe region including the PRC (Figure 1). Subsequent group-level analyses included only voxels with group mean TSNR > 40.

Figure 1.

Temporal Signal to Noise Ratio (TSNR) around perirhinal cortex is sufficient for detection of BOLD activity. Colour bar shows group mean TSNR, where a minimum of 40 is needed to detect BOLD activity. Slice positions are reported in MNI coordinates and shown as dotted lines on the axial section.

Group-level random effects analyses were run by entering parameter estimate images from each participant’s GLM into one-sample t-tests or F contrasts. Results were thresholded at voxel-level p < .01 uncorrected and cluster-level p < .05 with family-wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons. In order to explore more completely the a priori predictions that Sharedness would modulate activity in the fusiform gyri and CxD activity in the perirhinal cortex we reported additional results using a lower cluster size threshold. This is especially critical with respect to the predicted effects of Correlation × Distinctiveness in the PRC, since this region is known to show small changes in BOLD signal (Cohen & Bookheimer, 1994). For this reason, results for Correlation × Distinctiveness are shown both at the standard threshold noted above and at a reduced threshold of cluster-level p < .05 uncorrected, including only those voxels with low but reliable signal (i.e. intermediate TSNR between 40 and 100). Given our a priori hypothesis that Sharedness would modulate activity within the fusiform gyrus, we examined the effect of Sharedness within the fusiform gyrus without cluster-level threshold. We defined the extent of the fusiform region of interest using the Harvard-Oxford atlas (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/Atlases). Voxels were included if the atlas labelled them as “temporal fusiform cortex, posterior division” or “temporal occipital fusiform cortex” with a probability >10%.

In follow-up analyses, we determined whether Sharedness generated differential activity in medial and lateral fusiform gyri, and whether this tracked category effects in the fusiform (Chao, et al., 1999). We defined linear regions of interest (ROIs) in each hemisphere as lines of voxels between medial and lateral points in the fusiform gyri in three coronal planes at MNI y = −48, −57 and −66 mm (Figure 4, centre column). These planes crossed the anterior, middle and posterior parts of the category effects reported by Chao et al. (1999). We avoided examining activity in successive sagittal planes (i.e. from medial to lateral along the x-axis in MNI space), as this is relatively imprecise and may dilute effects by including non-responsive voxels. Instead, we defined linear ROIs following the actual anatomy of the fusiform which is slightly oblique to the x-axis in MNI space. Parameter estimates were extracted from successive voxels along the linear ROIs from two additional GLMs, the first based on explicit categories (living and nonliving) and second on the Sharedness variable. As in the main model described above, modulators were orthogonalised serially, with the eight visual parametric modulators entered first. The ninth parametric modulator was either category membership (+1 for living, −1 for nonliving) or the Sharedness value for each concept. In this way we examined the differential sensitivity of medial and lateral fusiform gyri to category-level information defined either explicitly or using feature statistics in two separate but comparable models.

Figure 4.

Activity patterns within the fusiform gyrus for the contrast of living vs. nonliving objects closely track the correlation with Sharedness, but not the correlation with CxD. Linear ROIs (centre column; see Imaging Analyses) traversing the fusiform gyri at y = −48 mm (A), −57 mm (B) and −66 mm (C) were used to extract activity values (t-values) in successive voxels from left to right. The resulting plots (left and right columns) confirm region-specific similarities in activation between the living vs. nonliving contrast (black) and the correlation with Sharedness (solid grey) but not the correlation with CxD (dashed grey). Regions responding preferentially to living things (relative to nonliving things) also respond to concepts with relatively more shared features, and regions responding preferentially to nonliving things (relative to living things) also respond to concepts with relatively fewer shared features. In contrast, these regions are not modulated by the requirement for feature integration (CxD). The fine and course dashed horizontal reference lines indicate t-values corresponding to p < .01 and .001, respectively.

Results

Picture naming performance

73% of responses were scored as correct according to the criteria described in the fMRI procedure. A further 8% identified the correct concept, but using a verbal label which did not correspond to that in the property norm study (e.g. “loaf” instead of “bread”). Of the remaining 19% of responses scored as incorrect, 4% were no responses, 2% stutters and 13% incorrect concept (e.g. “lion” instead of “tiger”). This accuracy rate is comparable to those obtained in other studies using large sets of pictures and similar criteria for coding errors (e.g. Alario et al., 2004; Barry, Morrison, & Ellis, 1997; Graves, Grabowski, Mehta, & Gordon, 2007; Levelt, Schriefers, Meyer, Pechman, & Vorberg, 1991; Taylor et al., 2012). The mean (± standard deviation) overt basic-level naming latencies over all correct items was 965 (± 77) (see Table 1), comparable with previous studies fMRI (e.g. Graves et al., 2007).

Object-related activity in the ventral stream

To identify the neural regions associated with object processing, BOLD activity associated with the correctly named [74%] objects was contrasted with the phase-scrambled images (voxel-level p < .001, cluster-level p < .05 FWE). We found activity throughout the occipital lobes and bilateral ventral streams through to posterior PRC, extending to right anterior PRC and hippocampus and left amygdala (Figure 2, left), and also in bilateral ventral precentral cortices and left orbitofrontal cortex, replicating previous findings (Tyler, et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Brain activity associated with picture naming. Top: contrast of basic-level naming vs. scrambled images overlaid on the ventral cerebral surface. Activation specific to naming meaningful objects (controlling for verbal output) was found along the anterior to posterior extent of the ventral stream. Bottom: activity explained by the visual model, where effects were focused in the bilateral occipital poles, with weaker effects extending to the posterior parts of the fusiform and inferior temporal gyri (see text for details). Colour bars represent voxel t- and F- values (degrees of freedom).

The following analyses focus on the visual and feature statistics variables (see Task Design and Materials). We first correlated BOLD responses with visual features, represented by eight PCA components derived from the Gabor-filtered images. These eight regressors were entered into a one-way ANOVA and tested using an “effects of interest” F-contrast. Because this contrast tests for voxels showing a response to any one of the eight visual regressors, we report results using a more conservative voxel-level threshold of p < .05 FWE with a minimal cluster-size threshold of 10 voxels, since correction was applied at the voxel level. Significant main effects were observed in the bilateral occipital poles (Figure 2, right; peak voxels in each hemisphere: MNI 12, −90, −3 mm, F(8,98) = 88.3, and MNI 15, −90, 0 mm, F(8,98) = 88.1), similar to previous results (e.g. Kwong, et al., 1992). Outside the occipital lobe, we found weaker activation extending anteriorly along the fusiform and lingual gyri (peak voxels outside occipital lobe: MNI 27, −51, −9 mm, F(8,98) = 23.8 and MNI −24, −48, −9 mm, F(8,98) = 21.2) to the posterior end of the inferior temporal gyrus.

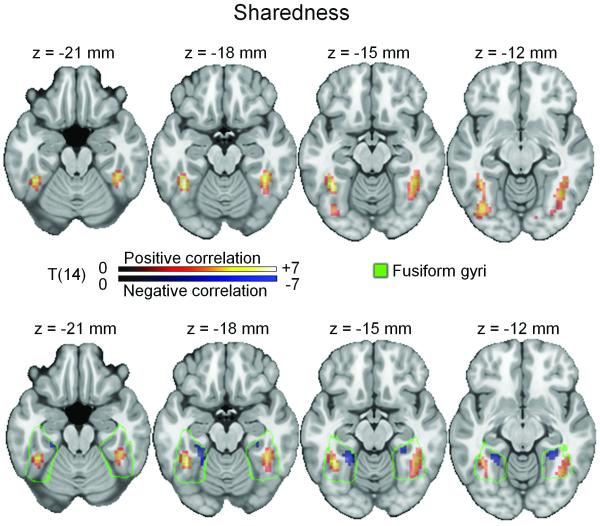

Objects with higher values on the Sharedness variable (i.e. greater degree of feature sharedness) produced greater activity in bilateral lateral fusiform gyri (Figure 3, top; peak voxels MNI 42, −39, −27 mm, T(14)=4.9 and MNI −39, −48, −18 mm, T(14) = 4.2) and posterior occipital and ventral occipitotemporal regions (peak voxel MNI 12, −90, 3 mm, T(14) = 6.5). These regions corresponded to those previously reported as showing greater activity to animals than tools (Chao, et al., 1999). To further explore these effects, in particular for effects in medial fusiform regions, we examined activity within the fusiform gyrus without cluster-level FWE correction (Figure 3, bottom). At this threshold we saw the same positive effect of Sharedness in the lateral fusiform, and in addition a negative effect of sharedness, corresponding to increased activity for objects with lower values of the Sharedness variable (i.e. fewer shared features) in bilateral medial fusiform gyri (peak voxels MNI 30, −45, −9 mm, T(14) = 3.8 & MNI −24, −45, −15 mm, T(14) = 3.6). This result is consistent with previous reports of greater activity in medial fusiform gyri to tools than animals (Chao, et al., 1999).

Figure 3.

Sharedness of object features modulates BOLD activity within the fusiform gyrus. Top: objects with relatively more shared features were associated with greater BOLD activity in the bilateral lateral fusiform gyri, regions previously associated with activity for animals (Chao, et al., 1999; Martin, 2007), consistent with the greater number of shared features in animals than tools (voxel-level threshold p < .01, cluster-level threshold p < .05 FWE). Bottom: the a priori prediction that Sharedness would differentially modulate the medial and lateral fusiform gyri was tested within an anatomically-defined fusiform region of interest without cluster-level thresholding. Objects with more shared features (orange) produce activity in lateral fusiform and with fewer shared features (blue; corresponding to tools) produce activity in the bilateral medial fusiform gyri. Slice positions are given as MNI coordinates and colour bars represents voxel t-values (degrees of freedom).

We then examined anatomical variability of activity within the fusiform gyri along lines of voxels traversing the fusiform gyrus from medial to lateral sites (see Imaging Analyses and Figure 4, centre column). Medial and lateral fusiform regions showed opposite effects, with lateral regions more active for items with more shared features and medial regions more active for objects with less shared features (Figure 4, grey lines on plots). Lateral voxels at MNI X = +/− 36 to 39 mm typically showed the highest positive correlation with Sharedness, whereas medial voxels at MNI X = +/− 24 to 27 mm typically showed the lowest negative correlation. Moreover, the medial to lateral pattern of activity for the Sharedness variable tracked closely with the pattern produced by contrasting the explicit categories “living” and “nonliving” (Figure 4, black lines on plots): the lateral fusiform gyri responded more to living things (which typically have more shared features) whereas the medial fusiform gyri showed the reverse pattern, responding more to nonliving things (which have fewer shared and more distinctive features). To confirm that the living and non-living objects used in this study differed in their degree of sharedness, we compared the Sharedness values for the living and non-living objects. Consistent with previous studies, living things had significantly greater feature sharedness (mean Sharedness = .53, SD = .12) than non-living things (mean Sharedness = .40, SD = .14; difference between mean living and non-living; t(386) = 9.27, p < .0001).

The effects of the Correlation × Distinctiveness variable showed that objects whose distinctive features were relatively more weakly correlated than their shared features (typical of living things) elicited stronger activity in the anteromedial temporal cortex, primarily left perirhinal and entorhinal cortices (Figure 5, left panel; peak voxel: MNI −24, −21, −27 mm, T(14) = −6.9). There were no significant activations associated with relatively more strongly correlated distinctive compared to shared features. We further explored these effects at a reduced threshold (see Imaging Analyses). While the positive contrast remained nonsignificant, the negative contrast now revealed bilateral PRC activation associated with naming concepts with relatively more weakly correlated distinctive than shared features (see Figure 5, right panel; peak voxels: −24, −21, −27, T(14) = −6.9 and 39, −24, −24, T(14) = −6.0). Two small clusters were also found in the left medial superior and orbital frontal lobe (peak voxels: MNI −6, 63, 37 mm, T(14) = −5.1 and MNI −3, 57, 36 mm, T(14) = −4.29). Since distinctive features must be integrated with a concept’s shared features for basic-level identification, confusable concepts with relatively weakly correlated distinctive features require more complex feature integration processes supported by the bilateral PRC for their unique identification (Taylor, Devereux, & Tyler, 2011; Tyler & Moss, 2001).

Figure 5.

The feature statistic Correlation × Distinctiveness modulates BOLD activity in anteromedial temporal cortex. Top: Objects with lower Correlation × Distinctiveness values – indicating relatively weakly correlated distinctive features requiring more complex feature integration processes for their unique identification – were associated with greater activity in the anteromedial temporal cortex including the left perirhinal cortex at voxel-level p < .01, cluster-level p < .05 FWE. Bottom: At voxel-level p < .01, uncorrected cluster-level p < .05 in voxels with intermediate TSNR of 40-100, bilateral perirhinal cortex activation was seen. To maximize anatomic localizability of the clusters with respect to the PRC (Pruessner, et al., 2002), clusters are shown on the average participant brain. Slice positions are reported as MNI coordinates and the colour bar represents voxel t-values (degrees of freedom).

Discussion

In this study we used a feature-based model of semantics to determine how two key aspects of object semantics – object-specific and category information – are neurally represented and processed. This feature-based approach to object representations in the brain has previously been validated in cognitive studies which show that feature statistics affect conceptual processing (Cree, McRae, & McNorgan, 1999; McRae, et al., 1997; Pexman, et al., 2003; Randall, et al., 2004; Taylor, et al., 2012). The statistics used in these experiments are based on features obtained from large scale property norming studies (e.g. McRae, et al., 2005). Participants in property norm studies are biased to report salient, verbalisable and distinguishing features (McRae et al., 1997, 2005; Tyler et al., 2000). While it is assumed that these biases do not interact with concept type or category, this assumption requies experimental validation. Thus, while feature statistics derived from feature norm studies are generally regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for characterising the semantics of concepts, surpassing semantic feature data obtained using automatic extraction algorithms on large scale corpora (Devereux, Pilkington, Poibeau, & Korhonen, 2010), the inherent biases in feature norming data represent a potential limitation in any study using these data. Behavioural studies have shown that a variety of feature statistics – including those used here – affect behavioural responses (McRae, et al., 1997; Randall, et al., 2004; Taylor, et al., 2012). For example, Taylor et al (2012) showed that shared features facilitated category decisions on objects, while the ease with which distinctive features could be integrated into a concept (as measured by the Correlation × Distinctiveness variable) facilitated object-specific identification, reflecting the functional relevance of different types of information carried by the relationship between different features within a concept.

Consistent with the behavioural studies, in the present experiment we found that feature statistics, reflecting different aspects of an object’s meaning, activated different neural regions. Sharedness – which captures the degree to which a concept’s features are shared with other concepts and thus forms the basis of category organisation – modulated activity within the fusiform gyri. Moreover, we found greater activation in lateral fusiform gyri for objects with higher sharedness and greater activation in medial fusiform gyri for objects with lower sharedness. This profile of lateral to medial activity within each hemisphere closely tracked activity for living and nonliving things, with greater sharedness showing similar effects as living things and less sharedness showing similar effects as nonliving things. This correspondence between the effects of sharedness and living things is consistent with the claim that living things have higher proportions of shared properties than nonliving objects (Cree & McRae, 2003; Randall, et al., 2004; Rosch, et al., 1976), a pattern replicated in the present set of objects where living things had more shared properties than nonliving things. Feature-based models of semantics claim that category structure (e.g. living, nonliving things) is an emergent property of feature statistics (Cree & McRae, 2003; Durrant-Peatfield, Tyler, Moss, & Levy, 1997; Garrard, Lambon Ralph, Hodges, & Patterson, 2001; Tyler & Moss, 2001; Vigliocco, et al., 2004), raising the possibility that features may provide an organising principle for category structure in the brain. However, this is a difficult hypothesis to test empirically because of the inherent interdependence between sharedness and category.

In contrast to the effects in the fusiform, feature statistics which differentiate between similar objects and enable object-specific representations were associated with aMTL activity, including in the bilateral perirhinal cortices. These results further support the view that the meaning of concrete objects is neurally coded in terms of feature-based representations. Taken together, the present findings suggest a hierarchy of semantic processing in the ventral stream with similar computational properties as has been proposed for the hierarchical model of perceptual object processing developed in non-human primates (Taylor, et al., 2011; Taylor, Moss, & Tyler, 2007; Tyler, et al., 2004). This perceptual model claims that simple visual features are coded in posterior ventral occipital sites, with increasingly more complex feature combinations computed from posterior to anterior regions in ventral temporal cortex (Tanaka, 1996; Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982). Non-human primate IT neurons code for moderately complex features (Tanaka, 1996), while perirhinal cortex, at the endpoint of this hierarchical system, generates feedback signals to bind the relevant information in IT cortex together (pair-coding properties) (Higuchi & Miyashita, 1996), thereby coding for the most complex feature combinations necessary to disambiguate highly confusable objects (Bussey, et al., 2002; Murray, et al., 2007). Critically, non-human primate research also demonstrates that the ventral stream codes not only perceptual object properties, but also the meaning of these properties (Hoffman & Logothetis, 2009; Sigala & Logothetis, 2002). Such findings demonstrate that in contrast to the less flexible, retinotopic coding at the posterior end of the ventral stream, information represented in the anterior region becomes tuned to meaningful, task-relevant features with experience. Moreover, just as the visual hierarchy is achieved by recurrent activity between posterior and anterior sites within the ventral stream (Hegdé, 2008), so communication between the fusiform and aMTL during object processing is underpinned by recurrent activity between these two regions (Clarke, Taylor, & Tyler, 2011).

The finding that the two anatomically distinct regions identified with category selectivity in previous studies – aMTL and fusiform – are sensitive to different aspects of an object’s semantic features supports the suggestion that posterior and anterior sites differ in their ability to integrate less or more complex semantic feature conjunctions, respectively. In the present study we found that feature statistics which capture the similarity between objects (shared features) were associated with activity in fusiform regions previously linked to category-specific responses (Martin, 2007). Category responses (e.g. viewing, matching) require simpler feature conjunctions than those needed for fine-grained differentiation between similar objects within a category; these latter involve the most complex feature conjunctions (Moss, et al., 2005; Tyler, et al., 2004) which are reflected in our second measure of Correlation × Distinctiveness. This measure captures the relative strength of the correlation for distinctive and shared features within an object, and thus the ease with which features can be integrated, thus enabling similar objects to be successfully differentiated from each other. According to property norm data, these are typically living things, especially animals (Taylor, et al., 2012; Taylor, et al., 2008; see also Table 1). The present results show that objects with this statistical profile engage the aMTL, especially the PRC, more than objects whose distinctive features are strongly correlated with its other features and are thus easier to differentiate one from another.

These results are consistent with neuropsychological studies demonstrating that patients with aMTL damage which includes the PRC have particular problems differentiating between highly similar objects, especially animals (Tyler & Moss, 2001). These patients exhibit a very specific kind of category-specific deficit; they have considerable difficulties with the distinctive properties of objects and thus are unable to differentiate similar objects from each other. Thus, they have little difficulty in identifying an object’s category but cannot differentiate between members within the same category. Moreover, this problem is much more pronounced for living than non-living things (Moss, Tyler, & Devlin, 2002; Moss, Tyler, Durrant-Peatfield, & Bunn, 1998; Tyler & Moss, 2001). The feature-based model described here can account for this behavioural effect in patients and its association with a specific neural region.

Supporting evidence for a posterior to anterior shift in neural activity in terms of the types of integration computations required comes from studies which manipulate the subject’s task and consequently the kind of conceptual representation required (Clarke, et al., 2011; Tyler, et al., 2004). These task manipulations require subjects to process an object at different levels of specificity – as a member of a category or as a specific object (animal, camel). Naming an object as a member of a category requires simpler feature conjunctions and activity is confined to posterior sites. Making an object-specific response to the same object, which requires the computation of more complex feature conjunctions, also engages aMTL (Barense, Henson, Lee, & Graham, 2010; Moss, et al., 2005; Tyler, et al., 2004). This is consistent with the notion that both perceptual and conceptual object processing progresses from a coarse to fine-grained analysis along the ventral stream (Clarke et al., 2013; Taylor, et al., 2012; Tyler, et al., 2004). The use of a basic-level naming task in the present study ensured functional activity along the entire ventral stream (Tyler et al., 2004) as well as the integration of distinctive with shared object features required for unique object identification, thus enabling the measurement of the effects of both the relative proportion of shared features and the relative correlational strength of shared and distinctive features.

In conclusion, this study suggests that a conceptual hierarchy, analogous to the perceptual hierarchy, and based on semantic feature statistics which capture statistical regularities of concepts experienced in the world, underpins the recognition of meaningful objects in the ventral temporal cortex. By combining a cognitive model of semantic representations with a neurobiological model of hierarchical processing in the ventral stream, it accounts for variation in neural activity as a function of the semantic structure of individual objects and the relationship between objects, and provides a unifying framework for heretofore unconnected findings of category responses in the fusiform (e.g. Chao, et al., 1999) and category effects in anteromedial temporal cortex (Moss, et al., 2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council (G0500842) to LKT; a British Academy (grant number LRG-45583) grant to LKT and KIT; a Newton Trust grant to LKT and KIT; by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC (grant agreement number 249640) to LKT; and by a Swiss National Science Foundation Ambizione Fellowship (grant number PZ00P1_126493) to KIT.

We are very grateful for the training data for FIRST, used to create the Harvard-Oxford atlas, particularly to David Kennedy at the CMA, and also to: Christian Haselgrove, Centre for Morphometric Analysis, Harvard; Bruce Fischl, Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, MGH; Janis Breeze and Jean Frazier, Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatric Research Program, Cambridge Health Alliance; Larry Seidman and Jill Goldstein, Department of Psychiatry of Harvard Medical School; Barry Kosofsky, Weill Cornell Medical Center.

References

- Alario FX, Ferrand L, Laganaro M, New B, Frauenfelder UH, Segui J. Predictors of picture naming speed. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers: a journal of the Psychonomic Society, Inc. 2004;36(1):140–155. doi: 10.3758/bf03195559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Gaffan D, Graham K. The human medial temporal lobe processes online representations of complex objects. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2963–2974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Henson RNA, Graham KS. Perception and conception: Temporal lobe activity during complex discriminations of familiar and novel faces and objects. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(10):3052–3067. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Henson RNA, Lee ACH, Graham KS. Medial temporal lobe activity during complex discrimination of faces, objects, and scenes: effects of viewpoint. Hippocampus. 2010;20(3):389–401. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Morrison C, Ellis A. Naming the Snodgrass and Vanderwart pictures: effects of age of acquisition, frequency, and name agreement. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1997;50A:560–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, Murray EA. Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in complex visual discriminations. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;15(2):365–374. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao LL, Haxby JV, Martin A. Attribute-based neural substrates in temporal cortex for perceiving and knowing about objects. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2(10):913–919. doi: 10.1038/13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Taylor KI, Devereux B, Randall B, Tyler LK. From Perception to Conception: How meaningful objects are processed over time. Cerebral Cortex. 2013;23(1):187–197. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Taylor KI, Tyler LK. The evolution of meaning: Spatiotemporal dynamics of visual object recognition. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(8):1887–1899. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Bookheimer SY. Localization of brain function using magnetic resonance imaging. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17(7):268–277. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree GS, McNorgan C, McRae K. Distinctive features hold a privileged status in the computation of word meaning: Implications for theories of semantic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32(4) doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.4.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree GS, McRae K. Analyzing the factors underlying the structure and computation of the meaning of chipmunk, cherry, chisel, cheese, and cello (and many other such concrete nouns) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:163–201. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree GS, McRae K, McNorgan C. An attractor model of lexical conceptual processing: simulating semantic priming. Cognitive Science. 1999;23(3):371–414. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux BJ, Pilkington N, Poibeau T, Korhonen A. Towards unrestricted, large-scale acquisition of feature-based conceptual representations from corpus data. Research on Language and Computation. 2010;7(2):137–170. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant-Peatfield MR, Tyler LK, Moss HE, Levy JP. The distinctiveness of form and function in category structure: A connectionist model. In: Shafto MG, Langley P, editors. Proceedings of the19th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard P, Lambon Ralph MA, Hodges JR, Patterson K. Prototypicality, distinctiveness, and intercorrelation: Analyses of the semantic attributes of living and nonliving concepts. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2001;18:125–174. doi: 10.1080/02643290125857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotts SJ, Plaut DC. Connectionist approaches to understanding aphasic perseveration. Seminars in Speech and Language. 2004;25(4):323–334. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-837245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves W, Grabowski T, Mehta S, Gordon J. A neural signature of phonological access: distinguishing the effects of word frequency from familiarity and length in overt picture naming. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:617–31. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin R, Lupker SJ, McRae K. Shared features dominate semantic richness effects for concrete concepts. Journal of Memory and Language. 2009;60(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegdé J. Time course of visual perception: coarse-to-fine processing and beyond. Progress in neurobiology. 2008;84(4):405–439. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Miyashita Y. Formation of mnemonic neuronal responses to visual paired associates in inferotemporal cortex is impaired by perirhinal and entorhinal lesions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(2):739–743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KL, Logothetis NK. Cortical mechanisms of sensory learning and object recognitino. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2009;364(1515):321–329. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys GW, Forde EME. Hierarchies, similarity, and interactivity in object recognition: category-specific neuropsychological deficits. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24(3):453–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay K, Naselaris T, Prenger R, Gallant J. Identifying natural images from human brain activity. Nature. 2008;452:352–356. doi: 10.1038/nature06713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil FC. The acquisition of natural kind and artifact terms. In: Domopoulous W, Marras A, editors. Language learning and concept acquisition. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1986. pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kivisaari SL, Tyler LK, Monsch AU, Taylor KI. Medial perirhinal cortex disambiguates confusable objects. Brain. 2012;135(12):3757–3769. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, Goldberg IE, Weisskoff RM, Poncelet BP, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(12):5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levelt WJM, Schriefers H, Meyer AS, Pechman T, Vorberg D. The time course of lexical access in speech production: A study of picture naming. Psychological Review. 1991;98(1):122–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon BZ, Caramazza A. Concepts and categories: A cognitive neuropsychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malt BC, Smith E. Correlated properties in natural categories. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1984;23(2):250–269. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. The representation of object concepts in the brain. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:25–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Cree GS. Factors underlying category-specific semantic deficits. In: Forde EME, Humphreys GW, editors. Category-specificity in brain and mind. Psychology Press; Hove, UK: 2002. pp. 211–249. [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Cree GS, Seidenberg MS, McNorgan C. Semantic feature production norms for a large set of living and nonliving things. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37:547–559. doi: 10.3758/bf03192726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, de Sa VR, Seidenberg MS. On the nature and scope of featural representations of word meaning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1997;126(2):99–130. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.126.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirman D, Magnuson JS. Attractor dynamics and semantic neighborhood density: processing is slowed by near neighbors and speeded by distant neighbors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34(1):65–79. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Rodd JM, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, Tyler LK. Anteromedial temporal cortex supports fine-grained differentiation among objects. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15(5):616–627. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Tyler LK, Devlin JT. The emergence of category-specific deficits in a distributed semantic system. In: Forde EME, Humphreys GW, editors. Category specificity in brain and mind. Psychology Press; Hove, UK: 2002. pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Tyler LK, Durrant-Peatfield M, Bunn EM. ‘Two eyes of a see-through’: Impaired and intact semantic knowledge in a case of selective deficit for living things. Neurocase. 1998;4(4-5):291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Tyler LK, Jennings F. When leopards lose their spots: Knowledge of visual properties in category-specific deficits for living things. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14(6):901–950. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Bodurka J, Bandettini PA. How long to scan? The relatinoship between fMRI temporal signal to noise and necessary scan duration. Neuroimage. 2007;34(2):565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Bussey TJ. Perceptual-mnemonic functions of the perirhinal cortex. Trends In Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3(4):142–151. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. Visual perception and memory: A new view of medial temporal lobe function in primates and rodents. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2007;30:99–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naselaris T, Prenger R, Kay K, Oliver M, Gallant J. Bayesian reconstruction of natural images from human brain activity. Neuron. 2009;63:902–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S, Vu AT, Naselaris T, Benjamini Y, Yu B, Gallant J. Reconstructing visual experiences from brain activity evoked by natural movies. Current Biology. 2011;21:1641–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noppeney U, Patterson K, Tyler LK, Moss H, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, et al. Temporal lobe lesions and semantic impairment: a comparison of herpes simplex virus encephalitis and semantic dementia. Brain. 2007;130:1138–1147. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Op de Beeck HP, Torfs K, Wagemans J. Perceived shape similarity among unfamiliar objects and the organization of the human object vision pathway. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(40):10111–10123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2511-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pexman PM, Holyk GG, Monfils MH. Number-of-features effects and semantic processing. Memory & Cognition. 2003;31(6):842–855. doi: 10.3758/bf03196439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Kohler S, Crane J, Pruessner M, Lord C, Byrne A, et al. Volumetry of temporopolar, perirhinal, entorhinal and parahippocampal cortex from high-resolution MR images: considering the variability of the collateral sulcus. Cerebral Cortex. 2002;12(12):1342–1353. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.12.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall B, Moss HE, Rodd JM, Greer M, Tyler LK. Distinctiveness and correlation in conceptual structure: behavioral and computational studies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30(2):393–406. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(3):510–532. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TT, Hocking J, Noppeney U, Mechelli A, Gorno-Tempini M, Patterson K, et al. Anterior temporal cortex and semantic memory: reconciling findings from neuropsychology and functional imaging. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;6(3):201–213. doi: 10.3758/cabn.6.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch E, Mervis CB, Gray WD, Johnson DM, Boyes-Braem P. Basic objects in natural categories. Cognitive Psychology. 1976;8:382–439. [Google Scholar]

- Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Buckmaster CA, Murray EA. Impairment and facilitation of transverse patterning after lesions of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus, respectively. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(1):108–115. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigala N, Logothetis NK. Visual categorization shapes feature selectivity in the primate temporal cortex. Nature. 2002;415:318–320. doi: 10.1038/415318a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Medin DL. Categories and concepts. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. Inferotemporal cortex and object vision. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:109–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Devereux BJ, Acres K, Randall B, Tyler LK. Contrasting effects of feature-based statistics on the categorisation and identification of visual objects. Cognition. 2012;122(3):363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Devereux BJ, Tyler LK. Conceptual structure: Towards an integrated neurocognitive account. Language and Cognitive Processes (Cognitive Neuroscience of Language) 2011;26(9):1368–1401. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2011.568227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Moss HE, Stamatakis EA, Tyler LK. Binding crossmodal object features in perirhinal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(21):8239–8244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509704103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Moss HE, Tyler LK. The conceptual structure account: a cognitive model of semantic memory and its neural instantiation. In: Hart J, Kraut M, editors. The neural basis of semantic memory. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 265–301. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Salamoura A, Randall B, Moss H, Tyler LK. Clarifying the nature of the distinctiveness by domain interaction in conceptual structure: comment on Cree, McNorgan, and McRae (2006) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34(3):719–725. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Moss HE. Towards a distributed account of conceptual knowledge. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2001;5(6):244–252. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler LK, Stamatakis EA, Bright P, Acres K, Abdallah S, Rodd JM, et al. Processing objects at different levels of specificity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16(3):351–362. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider L, Mishkin M. Two cortical visual systems. In: Ingle DJ, Goodale MA, Mansfiled RJW, editors. Analysis of visual behavior. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. pp. 549–586. [Google Scholar]

- Vigliocco G, Vinson DP, Lewis W, Garrett MF. Representing the meanings of object and action words: the featural and unitary semantic space hypothesis. Cognitive Psychology. 2004;48(4):422–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK, McCarthy R. Category-specific access dysphasia. Brain. 1983;106:859–878. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK, Shallice T. Category specific semantic impairments. Brain. 1984;107(3):829–854. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]