Abstract

Normal tissues are organized hierarchically with a small number of stem cells, able to self-renew and give rise to all differentiated cells found in the respective specialized tissues. The undifferentiated, multipotent state of normal stem cells is co-determined by the constituents of a specific anatomical space that hosts the normal stem cell population, called the ‘stem cell niche’. Radiation interferes not only with the stem cell population but also the stem cell niche, thus modulating a complex regulatory network. There is now mounting experimental evidence that many solid cancers share this hierarchical organization with their tissue of origin, with the cancer stem cells also occupying specialized niches. In this review we highlight some of the best-characterized aspects of normal tissue stem cells, cancer stem cells, and their niches in the bone marrow, gut and brain, as well as their responses to ionizing radiation.

Introduction

The radiation responses of protozoa and complex multicellular organisms share many aspects of the DNA damage repair process. However, in protozoa the stem cell is the organism itself and its survival after exposure to radiation only depends on the ability of the cell to cope with the DNA damage.

The functional integrity of higher multicellular organisms depends on compartmentalization, specialization, and hierarchy among cells. While the majority of cells in a tissue is dispensable and unable to reconstitute the tissue after damage, stem cells can produce all types of differentiated progeny found in a tissue. Thus stem cells have to be protected and supported in order to guarantee their function during the lifetime of the organism. The anatomic space in which stem cells are maintained and protected is the stem cell niche.

In this manuscript we will review: 1) recent advances in understanding of normal tissue stem cells, 2) characteristics of their niche, 3) their malignant counterparts and 4) summarize the current knowledge of the stem cell response to ionizing radiation.

The Normal Stem Cell Niche

Schofield was the first to introduce the concept of a stem cell niche as a stem cell-specific microenvironment. He suggested that such a niche would provide an anatomic space that determines the number of stem cells that can be supported, would be responsible for the maintenance of the stem cell phenotype, and would affect the mobility of stem cells [1].

One of the simplest and best-understood examples of a stem cell niche is found in the ovary of the fruitfly, Drosophila melanogaster, in which so called “cap cells” provide the physical space for a defined number of germinal stem cells and the signals to keep them in an undifferentiated state [2]. In higher organisms, niche components are less defined. In the following paragraphs we will discuss three mammalian stem cell niches that have been extensively studied in the past and which have significant relevance for the radiation responses of tissues during and after cancer treatment.

The bone marrow stem cell niche

Schofield originally developed the niche concept studying hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [1]. While not all components of the HSC niche have been defined, growing evidence suggests that the bone marrow contains at least two different types of niches: 1) One niche is found periosteal and provides a hypoxic environment, 2) a second niche is found in the perivascular location. However, in both locations nestin+ mesenchymal stem cells with adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic potential seem to play a mayor role for HSC maintenance and homing [3]. Interestingly, HSCs in the hypoxic niche can be eliminated by treatment with tirapazamine, a pro-drug that specifically targets hypoxic cells [4]. This indicates that hypoxia levels in this niche are severe enough to be physiologically meaningful. This raises two questions: 1) if there is a differential sensitivity of normal HSCs to radiation depending on their location in the bone marrow and 2) if hypoxic cell sensitizers have a yet to be-studied late toxicity to the hematopoietic system. In general, quiescent HSCs were found to be radioresistant compared to their lineage-committed progeny, rely on error-prone DNA repair and are thus susceptible to leukemogenesis [5].

The intestinal stem cell niche

Decades ago, the normal stem cell niche in the small intestine was found to be localized to the base of the crypts. It was generally accepted that the stem cells reside in position +4(+2 – +7) of the crypt base and that they cycle infrequently [6]. Subsequently they were found to be positive for the polycomb group protein BMI1 and the atypical homeobox protein Hopx [7]. This relatively rare type of BMI1+ cells is most abundant in the first 5 cm of the duodenum [8]. More recently, the Lgr5+crypt base columnar cells have been identified as a second type of intestinal stem cell [9]. This group of cells is intersected by Paneth cells, which derive from Lgr5+ cells and form the niche for the latter. However, Lgr5+were reported to be dispensable for crypt maintenance and appeared to be progeny of BMI1+ cells [8]. Conversely, Lgr5+ cells were reported to generate Hopx+ cells in position +4 suggesting the existence of two different intestinal stem cell niches. Further it was found that these populations can dynamically interconvert into each other [10].

The intestinal stem cell in position +4 has long been known to be exquisitely radiosensitive with almost all cells undergoing rapid apoptosis after irradiation with doses of 0.5 to 1 Gy [11]. Potten suggested that more radiation resistant progeny of these cells in position +5, +6, and +7, would retain some stem cell traits, enabling them to repopulate crypts after higher doses of radiation. However, a more recent report suggested that LGR5+ crypt base columnar cells are radioresistant intestinal stem cells and the source of repopulation after radiation injury [12].

The neural stem cell niche

Until the late 1960s [13] the adult central nervous system (CNS) had been considered post-mitotic but it is now clear that neural stem cells (NSCs) continuously contribute to tissue repair and plasticity in the adult brain.

The subgranular zone of hippocampal area and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles are the most prominent areas of adult neurogenesis. However, cells that fulfill criteria of NSCs by operational means can be found throughout the entire central nervous system including the cerebellum, retina, and spinal cord [14] suggesting that the CNS contains multiple NSCs niches that may serve different functions.

Our understanding of the anatomy of the NSC niche in the SVZ is quite advanced [14,15,16]. It appears that NSCs in the SVZ are located in a perivascular and an ependymalniche (Fig 1A). The exact phenotype of NCSs is still under debate but there is evidence that a nestin+/GFAP+ astrocyte population with direct contact to the vasculature contains the NSC population [15,16]. However, this might be specific for the SVZ and not necessarily the universal phenotype for NSCs in all niches in the CNS [14].

Figure 1.

Figure 1A The Neural Stem Cell Niche in the Subventricular Zone

Neural stem cells (NSCs)/type B1 cells (blue) are in contact with the endothelial cells of nearby blood vessel but also have contact to the ependymal cells (brown) and give rise to transiently amplifying/neural progenitor cells type C cells (dividing cell in light blue). Neural progenitor cells divide and produce neuroblast/type A cells (orange), which migrate into the periphery. Supporting astrocyte are illustrated in purple.

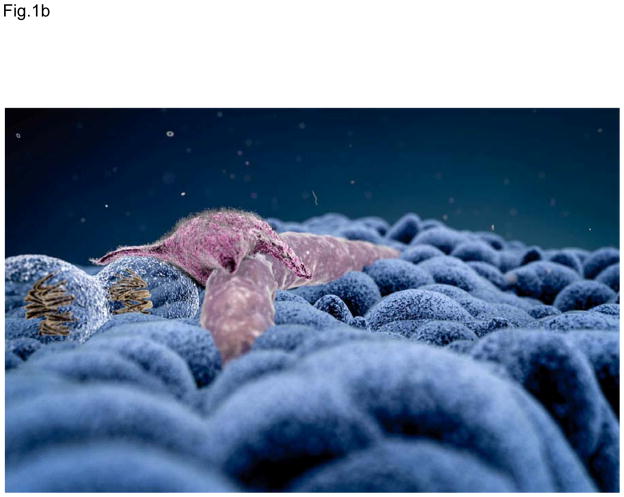

Figure 1B The Cancer Stem Cell Niche of Brain Tumors

The cancer stem cell niche of brain tumors recapitulates features of the normal neural stem cell niche. Cancer stem cells are found most frequently in proximity to endothelial cells.

Assessment of radiation responses of NSCs in-situ did, for the most part, rely on neurogenesis as an endpoint. As such most of these studies have investigated radiation responses of neural stem cells and committed progenitors cells. However, the general interpretation of the data is that NSCs are highly radiosensitive and that radiation inhibits neurogenesis [17]. Interestingly, over time different structures of the brain recover with different kinetics. While neural stem cells in the hippocampal area are depleted by radiation, neurogenesis in the SVZ can recover to some degree [18]. This indicates either differential radiosensitivity of NSCs in different niches in the brain, different numbers of NSCs are present at the time of irradiation or there is increased attraction of surviving NSCs into the stem cell niche in the SVZ.

Signaling in the Stem Cells Niche

The normal stem cell niche does not only provide an anatomical space to host stem cells but provides signals to maintain the stem cell state. In general, signaling involves soluble factors as well as cell bound receptor ligands and adhesion molecules expressed on the surface of stem cells and niche cells. These multiple points of regulation allow the niche to integrate long- and short-range signals to fine-tune stem cell fate decisions. We are only beginning to understand this complex network of positive and negative feedback regulation that underlies tissue homeostasis. Developmental signaling pathways like the Notch, Wnt, and Hedgehog pathways, signals are involved in tissue homeostasis mediated by the TGF-β protein family, and cadherin- and integrin-mediated adhesive interactions. Importantly, the signals required to maintain the stem cell state may vary widely for different tissues. However, in the context of tissue radiation responses, it is remarkable that many of the pathways involved, including the Notch [19] and the Wnt [20,21] pathway are activated, The expression of adhesion molecules like integrins [22] is also up-regulated in response to ionizing radiation. The resulting radiation-induced danger signal integrates the stem cell niche and stem cells into a tissue response that triggers wound healing and restores tissue integrity [23].

Cancer Stem Cells and Their Cell of Origin

The cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis [24] is an old concept [25] that gained new momentum after the first successful prospective identification of breast CSCs [26]. In many solid cancers cell populations enriched for CSCs can now be prospectively identified by cell surface marker profiles [26,27], ALDH activity [28], or lack of proteasome function [29]. Like in normal tissues, this model assumes hierarchy amongst the heterogeneous cell populations in solid cancers. It postulates the existence of a small population of CSCs, able to regrow the tumor after sublethal treatment that are capable of producing all lines of progeny found in the original tumor. The term ‘cancer stem cell’ does not necessarily imply that CSCs derive from normal tissue stem cells but instead indicates stem cell traits with regard to tumor initiation and maintenance. To avoid this confusion, CSCs are sometimes also called “tumor-initiating cells”. According to the CSC hypothesis, cancer cure can only be achieved if all CSCs are eliminated. This has important implications for anti-cancer treatments. Specifically, the CSC hypothesis explains why most anti-cancer drugs have failed and why, despite enormous financial efforts, progress against cancer has been slow and mainly been driven by prevention. Efficacy assessment of anti-cancer treatments is currently based on bulk tumor-responses and not on the response of CSCs. As such these bulk assessments may not be reliable indicators to select one drug over another.

Even though the term CSCs does not imply a specific cell of origin, experimental evidence from elegant animal experiments supports that normal tissue stem cells or progenitor cells are the cell or origin for CSCs. This was determined by experiments in which tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes were targeted in or to normal tissue stem cells and their differentiated progeny. In the gut [30], the brain [31] or the bone marrow [32] only stem cells/progenitor cells were capable of forming tumors after deletion of tumor suppressor genes or introduction of oncogenes. The same manipulations in differentiated progeny did not lead to tumor formation. Furthermore, more recently formal proof was provided. At least in mouse tumors- CSCs exist and maintain tumor growth [33,34,35].

An alternative model of tumor organization is the clonal evolution model [24], which has been and is favored by many in the field of oncology. It attributes the ability to gain features of a tumor-initiating cell to every cell in a tumor. It is attractive for many clinicians because it supports that the current clinical practice of treatment response assessment is indeed a valid approach. The most recent study to support this model, which gained broad attention, came from the Morrison lab showing that in very advanced melanoma cases 1 in 4 cells could initiate a xenograft if co-injected with Matrigel into severely immune-deficient NOD scid gamma (NSG, NOD. Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice. Further, melanoma CSCs markers did not identify cell populations with increased tumorigenicity [36]. However, this data has not been reproduced using CSCs from other solid tumors. In our hands, the use of NSG mice does increase tumor take in general, but it does not change the fact that prospectively identified CSCs from breast cancer or GBM have one to two magnitudes higher tumorigenicity than their differentiated progeny.

In essence, the CSCs hypothesis has gained broad acceptance since the first prospective identification of breast CSCs a decade ago and a growing body of evidence supports that undisturbed growing tumors are indeed organized hierarchically.

The cancer stem cell niche

A stem cell niche specific for CSCs has not been identified but if CSCs derive from normal tissue stem cells it is very likely that signals that support and maintain a stem cell phenotype in normal tissue stem cells will also support CSCs. For brain tumors the Gilbertson lab was able to demonstrate that CD133+ CSCs are preferentially found in close proximity to endothelial cells [37], thus resembling niche preferences similar to those of neural stem cells, the most likely cell of origin for CSCs in these types of tumors (Fig 1B). As a consequence, normal tissue stem cell niches may serve as a safe harbor for quiescent CSCs, which may cause recurrence if left untreated. Early evidence supporting this hypothesis came from our laboratory when we reported that higher radiation doses given to the SVZ of glioma patients correlated with significantly improved survival [38]. So far this observation has been independently confirmed by at least three other groups [39,40,41] and it may offer a promising approach to improve outcome for GMB patients. However, our findings are in conflict with historical clinical data from trials in which whole brain irradiation, where the SVZ was included in the target volume, did not lead to improved treatment outcome [42]. Therefore, this provocative hypothesis needs validation in a prospective trial.

An additional opportunity to improve radiation treatment outcome may lie in the tropism of CSCs to certain niches. First reported by Paget and leading to his ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis [25] it is generally accepted that metastatic spread does not follow a random distribution throughout the body or could be easily explained by differences in perfusion between different organs. In other words, while both breast cancer and prostate cancer, frequently spread to the bone, the former also frequently forms brain metastases while spread of prostate cancer to the central nervous system is extremely rare [43]. Also, even though glioblastomas are highly vascularized they almost never initiate visceral metastases. A deeper understanding of the signals that allow for homing of CSCs into specific niches, permissive for metastatic growth could lead to novel anti-cancer therapies that restrict cancers to their primary sites, which can often be controlled by radiation therapy.

Radiation response of CSCs and the CSC niche

One important aspect of CSCs is their relative resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and radiation. First described for GBM by the Rich lab [44] and for breast cancer by our lab [19], this radioresistance is based in the increased ability to scavenge free radicals formed in response to radiation [19] and differences in how DNA double-strand breaks are processed and repaired [19,44]. These observations have been reproduced by many other laboratories and for several different solid cancers. It is possible that these features are not necessarily acquired during carcinogenesis but rather inherited from their non-malignant stem cell of origin [5,12].

A consequence of the relative radioresistance of CSCs is that radiation enriches for CSCs. A general explanation for this observation has been selective killing of radiosensitive non-tumorigenic cells [19,44,45]. However, a closer look at the absolute numbers of breast and glioma CSCs before and 5 days after single doses of radiation and consideration of cell cycle duration and intrinsic radioresistance of CSCs indicated that radiation generates CSCs from previously non-tumorigenic cells [46]. This process was preferentially observed in a polyploid cell population and dependent on re-expression of epigenetically silenced transcription factors Klf4, Sox2, Nanog, and Oct4 [46,47], the same factors used to reprogram somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells [48,49]. Importantly, these cells did not only express CSC markers but were 32-fold more tumorigenic than the non-irradiated cells they originated from [46].

Irradiation of tissues leads to a pro-inflammatory microenvironment [23] and chronic inflammation has long been known to cause cancer. A recent report demonstrated that activation of NFκB signaling, the master regulatory pathway of inflammation [50], can dedifferentiate post-mitotic intestinal epithelial cells into CSCs [51]. Furthermore a hypoxic microenvironment, frequently found in human cancers and previously thought to protect cancer cells from radiation, also seems to promote acquisition of a CSCs phenotype by previously non-tumorigenic cells [52]. Eventhough we were not able to detect hypoxia-mediated radioprotection of CSC [53], areas of low oxygen tension could be the birthplace of de novo generated CSCs that led to tumor recurrence. Remarkably, radiation-induced reprogramming seems to be under tight negative feedback control by pre-existing CSCs [46] and may hold a key to improve radiation treatment outcome.

Taken together the current data suggest that neither the CSC hypothesis nor the clonal evolution model are exclusively correct but may rather describe tumor organization at different stages of a disease and under different micro-environmental conditions.

Concluding Remarks

Our understanding of normal and cancer stem cells and their respective niches is far from complete. However, from a radiobiological point of view it is common sense that the interaction of the stem cell with its niche co-determines the response to radiation. Dissecting these interactions is challenging but it may hold great promise to alter radiation treatment outcome in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

FP was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (RO1CA137110, 1R01CA161294) and the Army Medical Research & Material Command’s Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-11-1-0531).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu CH, Xie T. Clonal expansion of ovarian germline stem cells during niche formation in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:2579–2588. doi: 10.1242/dev.00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levesque JP, Winkler IG. Hierarchy of immature hematopoietic cells related to blood flow and niche. Current opinion in hematology. 2011;18:220–225. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283475fe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar K, Mauch P, Vergilio JA, Sackstein R, Down JD. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5431–5436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701152104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohrin M, Bourke E, Alexander D, Warr MR, Barry-Holson K, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error-prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell stem cell. 2010;7:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potten CS. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 1998;353:821–830. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nature genetics. 2008;40:915–920. doi: 10.1038/ng.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda N, Jain R, LeBoeuf MR, Wang Q, Lu MM, et al. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potten CS. Radiation, the ideal cytotoxic agent for studying the cell biology of tissues such as the small intestine. Radiation research. 2004;161:123–136. doi: 10.1667/rr3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua G, Thin TH, Feldman R, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Clevers H, et al. Crypt base columnar stem cells in small intestines of mice are radioresistant. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1266–1276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altman J, Das GD. Postnatal neurogenesis in the guinea-pig. Nature. 1967;214:1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/2141098a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decimo I, Bifari F, Krampera M, Fumagalli G. Neural stem cell niches in health and diseases. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18:1755–1783. doi: 10.2174/138161212799859611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doetsch F. A niche for adult neural stem cells. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2003;13:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, Louissaint M, Colonna L, et al. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2008;3:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fike JR, Rosi S, Limoli CL. Neural precursor cells and central nervous system radiation sensitivity. Seminars in radiation oncology. 2009;19:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellstrom NA, Bjork-Eriksson T, Blomgren K, Kuhn HG. Differential recovery of neural stem cells in the subventricular zone and dentate gyrus after ionizing radiation. Stem cells. 2009;27:634–641. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips TM, McBride WH, Pajonk F. The response of CD24(−/low)/CD44+ breast cancer-initiating cells to radiation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1777–1785. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su W, Chen Y, Zeng W, Liu W, Sun H. Involvement of Wnt signaling in the injury of murine mesenchymal stem cells exposed to X-radiation. International journal of radiation biology. 2012;88:635–641. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.703362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei LC, Ding YX, Liu YH, Duan L, Bai Y, et al. Low-dose radiation stimulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, neural stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis of the mouse hippocampus in vitro and in vivo. Current Alzheimer research. 2012;9:278–289. doi: 10.2174/156720512800107627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cordes N, Meineke V. Integrin signalling and the cellular response to ionizing radiation. Journal of molecular histology. 2004;35:327–337. doi: 10.1023/b:hijo.0000032364.43566.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McBride WH, Chiang CS, Olson JL, Wang CC, Hong JH, et al. A sense of danger from radiation. Radiat Res. 2004;162:1–19. doi: 10.1667/rr3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;1:571–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, et al. ALDH1 Is a Marker of Normal and Malignant Human Mammary Stem Cells and a Predictor of Poor Clinical Outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vlashi E, Kim K, Lagadec C, Donna LD, McDonald JT, et al. In vivo imaging, tracking, and targeting of cancer stem cells. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:350–359. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcantara Llaguno S, Chen J, Kwon CH, Jackson EL, Li Y, et al. Malignant astrocytomas originate from neural stem/progenitor cells in a somatic tumor suppressor mouse model. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Caro M, Cobaleda C, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Vicente-Duenas C, Bermejo-Rodriguez C, et al. Cancer induction by restriction of oncogene expression to the stem cell compartment. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:8–20. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, van den Born M, van Es JH, et al. Lineage Tracing Reveals Lgr5+ Stem Cell Activity in Mouse Intestinal Adenomas. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1224676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, et al. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. 2008;456:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature07567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evers P, Lee PP, DeMarco J, Agazaryan N, Sayre JW, et al. Irradiation of the potential cancer stem cell niches in the adult brain improves progression-free survival of patients with malignant glioma. BMC cancer. 2010;10:384. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta T, Nair V, Paul SN, Kannan S, Moiyadi A, et al. Can irradiation of potential cancer stem-cell niche in the subventricular zone influence survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma? Journal of neuro-oncology. 2012;109:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0887-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slotman BJ, Eppinga WSC, de Haan PF, Lagerwaard FJ. Is Irradiation of Potential Cancer Stem Cell Niches in the Subventricular Zones Indicated in GBM? International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology and Physics. 2011;81:S184. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen LL, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Ford E, McNutt T, Kleinberg L, et al. Increased Radiation Dose to the SVZ Improves Survival in Patients With GBM. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology and Physics. 2012;84:S8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma RR, Singh DP, Pathak A, Khandelwal N, Sehgal CM, et al. Local control of high-grade gliomas with limited volume irradiation versus whole brain irradiation. Neurology India. 2003;51:512–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatzoglou V, Patel GV, Morris MJ, Curtis K, Zhang Z, et al. Brain Metastases from Prostate Cancer: An 11-Year Analysis in the MRI Era with Emphasis on Imaging Characteristics, Incidence, and Prognosis. Journal of neuroimaging: official journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bao S. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woodward WA, Chen MS, Behbod F, Alfaro MP, Buchholz TA, et al. WNT/beta-catenin mediates radiation resistance of mouse mammary progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:618–623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagadec C, Vlashi E, Della Donna L, Dekmezian C, Pajonk F. Radiation-induced Reprograming of Breast Cancer Cells. Stem Cells. 2012 doi: 10.1002/stem.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salmina K, Jankevics E, Huna A, Perminov D, Radovica I, et al. Up-regulation of the embryonic self-renewal network through reversible polyploidy in irradiated p53-mutant tumour cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2099–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel M, Yang S. Advances in reprogramming somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;6:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao R, Daley GQ. From fibroblasts to iPS cells: induced pluripotency by defined factors. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:949–955. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwitalla S, Fingerle AA, Cammareri P, Nebelsiek T, Goktuna SI, et al. Intestinal Tumorigenesis Initiated by Dedifferentiation and Acquisition of Stem-Cell-like Properties. Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathieu J, Zhang Z, Zhou W, Wang AJ, Heddleston JM, et al. HIF induces human embryonic stem cell markers in cancer cells. Cancer research. 2011;71:4640–4652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagadec C, Dekmezian C, Bauche L, Pajonk F. Oxygen levels do not determine radiation survival of breast cancer stem cells. PloS one. 2012;7:e34545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]