Abstract

To better understand early predictors of weak language and academic abilities, we identified children with and without weak abilities at age 8. We then looked back at age 2 vocabulary and word combining, and evaluated these measures as predictors of age 8 outcomes. More than 60% of children with weak oral language abilities at 8 were not late talkers at 2. However, no word combining at 2 was a significant risk factor for poor oral language, reading comprehension, and math outcomes at 8. The association of no word combining with age 8 reading comprehension and math ability was mediated by age 8 oral language ability. The findings indicate that children take different developmental pathways to weak language abilities in middle childhood. One begins with a delayed onset of language. A second begins with language measures in the typical range, but ends with language ability falling well below typical peers.

Keywords: Late talking, Language disorders, Language impairment, Learning disabilities, Language development

1. Introduction

Weak oral language skills in middle childhood are a major concern for educators and parents. Children with poor oral language often have problems with academic and social functioning (Conti-Ramsden, Durkin, Simkin, & Knox, 2009; Whitehouse, Line, Watt, & Bishop, 2009) and in the long term, have more limited academic and vocational attainment (Clegg, Hollis, Mawhood, & Rutter, 2005). Oral language skills at school entry predict later reading skills (Scarborough, 1998) and children with weak oral language are more likely to have word reading, reading comprehension and math learning disabilities (Stothard, Snowling, Bishop, Chipchase, & Kaplan, 1998; Young et al., 2002).

From a clinical and educational perspective, it is desirable to predict, prior to kindergarten, which children will have weak language skills in middle childhood. Late talking is a widely studied indicator of language development at age 2, and is a risk factor for later weakness in language ability (Oliver, Dale, & Plomin, 2004; Reilly et al., 2010; Rice, Taylor, & Zubrick, 2008). Two main definitions of late talking are found in the literature. One definition uses vocabulary size, and usually classifies late talkers as those children falling below the 10th percentile of a normative sample (Henrichs et al., 2011; Reilly et al., 2010). The other definition is failure to combine two or more words by 24 months (Preston et al., 2010; Rice et al., 2008). In the present study, unlike most previous work, we employed both criteria, and compared the results that were obtained with each. This approach is supported by evidence that early word combining ability and early vocabulary size exhibit different patterns of heritability, suggesting that causal factors for delays in one may not be the same as for delays in the other (Van Hulle, Goldsmith, & Lemery, 2004).

Many late talkers later move into the range of normal age expectations for language (Ellis Weismer, 2007; Paul, Murray, Clancy, & Andrews, 1997; Rescorla, 2002); however, Rescorla (2005) has shown that measurable language and reading deficits exist in these “late bloomers.” Although considerable research has investigated how many and which late talkers will later catch up, and how they fare over time (Paul et al., 1997; Rescorla, 2002; Rice et al., 2008; Whitehurst & Fischel, 1994), less notice has been given to data suggesting that many children with weak language may not have a history of late talking (Ellis Weismer, 2007; Henrichs et al., 2011; Reilly et al., 2010). The existence of such children poses a predictive problem. What is the developmental pathway for children who have weak oral language in middle childhood but did not exhibit language delay as toddlers?

Several current theoretical approaches in developmental psychology propose that developmental trajectories are dynamic and multiply influenced in complex ways (Elman et al., 1996; Karmiloff-Smith, 1998; Sameroff, 2010). Individuals who begin with similar ability profiles may diverge as their differing genotypes interact with their differing environments, and small differences become larger over time. Conversely, individuals that begin with different genetic endowments may converge to similar ability profiles over time, despite different underlying etiologies (Karmiloff-Smith, 2007; Thomas & Karmiloff-Smith, 2002). In the current study, we started with oral language ability at middle childhood, and looked back to ask whether children with weak oral language had been late talkers. We hypothesized that there are two main developmental trajectories resulting in weak language ability at age 8. One, as found in many previous studies, begins with late language emergence at age 2 (Reilly et al., 2010; Rice et al., 2008). The second trajectory begins with “typical” language performance at age 2. A subset of these on-time talkers will follow a developmental pathway that diverges from peers who continue to develop typically, and will form a substantial proportion of the children with weak oral language at age 8.

Given the associations between weak oral language and weak academic skills that have been observed (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang, 2002; Gibbs & Cooper, 1989; Scarborough, 1998; Young et al., 2002), we also investigated whether late talking status at age 2 was predictive of poor reading and math skills at age 8. Rescorla (2002) and Preston et al. (2010) found that at middle childhood, late talkers performed at a lower level on reading measures compared to non-late talkers. We might therefore expect that oral language ability mediates any relationship between late talking and academic performance; however, factors that cause late talking might also directly cause academic difficulties. We used mediation analysis to assess the relationship between late talking, oral language, and academic skills. Mediation models are often used to evaluate causal relationships; however, our purpose was not to assess causality. We do not propose that late talking causes either weak oral language or weak academic skills. Rather, late talking may be an early indicator of either or both outcomes.

In this study, we evaluated evidence for varied developmental pathways to language weakness in middle childhood by measuring the proportions of children with weak oral language at age 8 who would and would not have been classified as late talkers at age 2, using data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development's Study of Early Childcare and Youth Development (SECCYD) (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1992). This unique population-based dataset provides measures that allow classification by language ability at age 2 and age 8, measures of academic ability, measures of general intelligence, and measures related to socio-economic status allowing us to examine relationships between academic skills and early and later language ability. Our research questions were as follows.

What proportions of children with weak oral language at age 8 would and would not have qualified as late talkers at age 2? How do those proportions vary by the measure of language emergence, i.e., vocabulary size vs. word combining?

Are late talking measures predictive of poor oral language outcomes and poor academic skills at age 8, independent of other plausible predictors?

If late talking is predictive of weak academic skills as well as weak oral language, does oral language mediate the relationship between late talking and academic skills?

2. Methods

To assess the late talking history of children with weak language skills at age 8, we identified children with poor oral language or poor academic skills (cases) and randomly selected children of the same age with normal range oral language or academic skills (controls). For both cases and controls, we obtained age 2 vocabulary and word combining ability measures and important covariates of language ability, including maternal education and non-verbal intelligence. When the case and control groups differed on the covariates, these differences were statistically controlled in the analyses (Hotopf, 1998). Control groups were approximately three times as large as the case groups to enhance the statistical power to detect associations of late talking with later language ability (Hotopf, 1998).

2.1. Participants

Participants were drawn from the SECCYD (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1992). There were 1015 children who participated in phase III of the longitudinal study, which included language and cognitive measures taken when the children were age 8 or 9. The study originally enrolled 1364 newborn children from 10 hospitals around the United States. Excluded from the study were children with serious medical issues at birth, mothers under age 18 at the child's birth, mothers who were known to be substance abusers, and mothers who did not speak English.

All participants qualified for the current study with scores of 74 or greater on the performance scale (PIQ) of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999) at age 9. The standard error for this measure was 4, so a score of 74 was selected to rule out intellectual disability.

2.2. Oral language measures

Children's oral language ability was measured using standard scores from the Picture Vocabulary and Memory for Sentences subtests of the Woodcock–Johnson Test of Cognitive Ability, Revised (WJ-R) (Woodcock & Johnson, 1990) and the Word Definitions subtest of the WASI. A fourth measure was narrative ability. Children told a story from a wordless picture book. The mean and SD of the narrative measure was determined by the complete SECCYD sample. The score was a total basedon component scores for narrative structure, language complexity, and emotional content. The narrative total score had a mean of 34.8, and 1 SD below the mean was 25.2 based on 987 available scores.

Both categorical and continuous measures of language and academic ability were used in this study. To assess proportions of children with oral language weakness and a late talking history, and the associations of late talking with poor oral language outcomes, a categorical variable for weak versus typical oral language ability was created (see Table 1 notes). For the mediation analyses, a continuous measure of oral language ability was developed (see Table 7 notes).

Table 1.

Proportions of late talkers among children with weak and typical oral language at age 8.

| Measure | Weak abilitya | Typical ability |

|---|---|---|

| Oral language N | 72 | 241 |

| Late talking measures at age 2 | ||

| Late: Vocabulary ≤10th percentileb | 36% | 18% |

| Typical: Vocabulary >10th percentile | 64% | 82% |

| Late: No word combiningc | 23% | 8% |

| Typical: Combining sometimes | 36% | 25% |

| Typical: Combining regularly | 40% | 67% |

Children with weak oral language at age 8 scored 1 SD or more below the mean on at least 2 of 4 oral language measures, or 2 SD or more below the mean on 1 oral language measure (Cohen et al., 1993). The age 8 oral language measures were the Picture Vocabulary and Memory for Sentences subtests of the Woodcock–Johnson Test of Cognitive Ability, Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1990), the Word Definitions subtest of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999), and the narrative ability total score from the SECCYD.

Late talking identified by expressive vocabulary at or below the 10th percentile of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI) (Fenson et al., 1993). Percentiles adjusted for sex of child. Parents completed checklist indicating words used by the child.

Late talking identified by parent report (MCDI) of whether the child was not yet combining words, combining words sometimes, or combining regularly.

Table 7.

Linear regression models to determine whether age 8 oral language ability mediated the effect of late talking (not combining words) at age 2 on academic skills at age 8.

| Predictor | b | t | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading comprehension | ||||

| 1. Direct effect of late talking (model fit) | 12.8 | .000 | ||

| Late talking statusa | -15.52 | 3.7 | .000 | |

| 2. Mediator (oral language at 8) added as | ||||

| predictor (model fit) | 105.5 | .000 | ||

| Oral language at 8 | 3.92 | 13.4 | .000 | |

| Late talking statusa | -6.35 | 2.2 | .031 | |

| 3. Late talking status as predictor of oral language at | ||||

| 8 (model fit) | 8.4 | .004 | ||

| Late talking statusa | -2.34 | 2.9 | .004 | |

| Broad math | ||||

| 1. Direct effect of late talking (model fit) | 10.6 | .001 | ||

| Late talking statusa | -13.38 | 3.3 | .001 | |

| 2. Mediator (oral language at 8) added as | ||||

| predictor (model fit) | 69.0 | .000 | ||

| Oral language at 8 | 4.10 | 11.0 | .000 | |

| Late talking statusa | -4.33 | 1.3 | .194 | |

| 3. Late talking as a predictor of oral language at 8 | ||||

| (model fit) | 12.8 | .000 | ||

| Late talking statusa | -2.21 | 3.5 | .000 |

Notes. The reading comprehension measure was the Passage Comprehension subtest standard score, and the math ability measure was the Broad Math subtest standard score, both of the Woodcock-Johnson Psychoeducational Battery, Revised (WJ-R). Oral language ability at age 8 was the sum of z-scores for Picture Vocabulary and Memory for Sentences subtests of the WJ-R, the Word Definitions subtest of the WASI, and the narrative total score from the SECCYD.

Late talking defined by an indicator variable for no word combinations at age 2 versus combining words at age 2.

2.3. Academic ability measures

The academic ability measures were the Word Attack, Passage Comprehension, and Broad Math subtests of the WJ-R. Scores at or below the 25th percentile were categorized as weak ability (Catts, Adlof, & Ellis Weismer, 2006; Lyon, 1996; Shaywitz et al., 2002). For the mediation analyses, continuous standard scores from these measures were used.

2.4. Late talking measures

Language at age 2 was assessed by two measures. The first was expressive vocabulary from the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI) (Fenson et al., 1993). The second was whether or not the child was combining words, also based on the MCDI.

2.5. Covariates

The PIQ of cases and controls was assessed with the WASI. The educational attainment of the participant's mother was an indicator variable for completion of high school or lower, or some college or higher attainment. The gender and race of the participant were also used as covariates.

2.6. Analytical approach

To determine the proportions of children with weak language abilities with and without a late talking history, the age 8 category (case, control) was linked to age 2 late talker status for each late talking criterion. To determine whether late talking status predicted age 8 language and academic ability weakness, a series of logistic regressions were conducted. In these regressions, late talking status was used to predict the categorical age 8 outcome. Where case and control groups differed by one or more of the potential covariates, the covariates were simultaneously entered into the regression as control variables. Model fit was evaluated by log-likelihood tests comparing intercept-only models to models with all predictors, evaluated on a chi square distribution. The statistic of primary interest from the logistic regressions was the odds ratio (OR). An OR of 1 indicates no effect of the predictor on the outcome. An OR greater than 1 indicates that the presence of the predictor (e.g. being a late talker) increases the likelihood that the child will have weak language or academic ability at age 8. An OR significantly less than 1 indicates a reduced likelihood of weak language or academic ability. Statistical significance was evaluated by observing whether the 95% confidence interval for the OR excluded 1.

To assess whether age 8 oral language mediates the effect of late talking on reading and math skills, single mediator analyses were conducted using the product of coefficients approach outlined by MacKinnon (2008). These linear regression analyses first determined whether late talking status predicted the continuous reading or math academic ability measures. Then the proposed mediator was entered with late talking as a predictor of academic ability. Finally, late talking status was evaluated as a predictor of age 8 oral language. The result was an estimation of the total effect of late talking on academic ability as well as the indirect effect, or the portion of the total effect that is mediated through age 8 oral language. Statistical significance of the indirect effect was evaluated with 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

3.1. Proportion of late talkers among age 8 children with weak language

The first question was what proportion of children with weak oral language at age 8 would have been classified as late talkers at age 2. Findings are summarized in Table 1. When late talking was identified by a restricted age 2 expressive vocabulary, a larger proportion of children with weak age 8 oral language abilities were late talkers as compared to controls, but a majority of children in both groups would not have been considered late talkers at age 2. When late talking was identified by the absence of word combining at age 2, a larger proportion of children with weak oral language at age 8 had a late talking history, but again most children in both groups would not have been considered late talkers.

3.2. Predictive value of late talking

Before evaluating the relation of late talking to age 8 language ability, the case and control groups were assessed for differences on potential covariates of language ability. Results are summarized in Table 2. The weak and typical oral language groups differed on PIQ, mother's education, and race. The groups did not differ on the proportion of males and females.

Table 2.

Summary of measures that may covary with oral language ability for children with weak oral language ability at age 8 (cases) and controls.

| Measure | Weak abilitya | Typical ability | Test | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance IQ M(SD) | 92.8 (13) | 107.1 (13) | t (359)=8.9 | .000 |

| Sex % male | 46% | 45% | χ2 (1) = .001 | .978 |

| Mother's ed. ≤ high school | 63% | 22% | χ2 (1) = 5.2 | .000 |

| Race % African American | 37% | 6% | χ2 (1) = 54 | .000 |

Children with weak oral language at age 8 scored 1 SD or more below the mean on at least 2 of 4 oral language measures, or2SD or more below the mean on 1 oral language measure (Cohen et al., 1993).

To evaluate how well late talking status predicts age 8 language weakness, we performed a logistic regression. The covariates of PIQ, mother's education and race were entered as control variables with late talking status. Race was a categorical indicator of African American or other race. A model using the age 2 restricted vocabulary criterion for late talking is summarized in Table 3, and reports the odds ratio associated with late talking adjusted for the covariates that differed between groups. The unadjusted ORs, which do not include effects of the covariates, are presented in the Appendix A.The model summarized inTable 3 was significant, χ2 (4)=99.3, p<.001. Mother's education, PIQ, and race were significantly related to age 8 language status, as indicated by 95% confidence intervals that excluded 1 for the odds ratios. Late talking status based on a restricted vocabulary, however, did not make a unique contribution to the model's prediction of age 8 oral language status.

Table 3.

Summary of logistic regression model predicting age 8 oral language status from age 2 late talking status, with control variables. Late talking defined as age 2 expressive vocabulary at or below the 10th percentile on the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI).

| Variable | b | SE | Odds ratio | 95% CI for odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIQ | -.072 | .014 | .931 | .905–.957 |

| Mother's education | 1.275 | .333 | 3.579 | 1.864–6.869 |

| Race | 1.216 | .428 | 3.373 | 1.456–7.810 |

| Below MCDI 10th percentile | .567 | .368 | 1.763 | .857–3.626 |

| Constant | 5.118 | 1.441 | 167.04 |

A model evaluating late talking using the not combining words criterion is summarized in Table 4. The model was significant, χ2 (5)=92.3, p<.001. Both age 8 PIQ and mother's education were associated with age 8 language status. Race did not significantly contribute to the model. Late talking defined as no word combinations at age 2 was a significant predictor of age 8 oral language status. Children not yet combining words were 2.8 times more likely to have weak oral language as compared to children combining words regularly. A model collapsing word combining to a dichotomous variable (combining, not combining) had a similar result (OR=2.5, 95% CI [1.04, 6.00]).

Table 4.

Summary of logistic regression model predicting age 8 oral language status from age 2 late talking status, with control variables. Late talking defined as not yet combining words at age 2.

| Variable | b | SE | Odds ratio | 95% CI for odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIQ | -.071 | .015 | .931 | .905–.959 |

| Mother's education | 1.328 | .338 | 3.77 | 1.95–7.310 |

| Race | .720 | .463 | 2.055 | .830–5.090 |

| Word combining: Often [referent] | ||||

| Not yet | 1.046 | .484 | 2.846 | 1.101–7.354 |

| Sometimes | .625 | .384 | 1.869 | .881–3.966 |

| Constant | 4.860 | 1.474 | 128.99 |

A model including the control variables and both indicators of late talker status (not combining words, restricted vocabulary) was compared to a model excluding the restricted vocabulary predictor. Adding the restricted vocabulary predictor did not add to the model's prediction (χ2 (1)=.175, p=.676).

Given the significant differences in the racial composition of the case and control groups, we first evaluated whether the proportions of late and typical talkers differed by race in the age 8 weak oral language group. For neither late talking criterion did proportions of late talkers differ by race. Seven of 20 African American children and 9 of 47 children from other racial groups were not combining words (χ2 (2)=3.03, p=.219). Ten of 25 African American children and 16 of 47 children from other racial groups had restricted vocabularies (χ2 (2)=1.30, p=.522).

To further evaluate whether the imbalanced racial make-up of oral language case and control groups was a determining factor in the results, we stratified groups by race. For the African American stratum, 20 cases (weak oral language) and 56 controls were identified with complete data at both age 8 and age 2. A cross tabulation of word combining status, mother's education, and age 8 oral language ability is presented in Table 5. Some cells in this cross tabulation were empty, suggesting that a multivariate logistic regression on these data may produce unstable results (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). For the White stratum, there were 45 cases and 233 controls identified. We performed a logistic regression with word combining status as the predictor of age 8 oral language status after adjusting for PIQ and the mother's education. The results were very similar to those for the mixed-race sample. The overall model was significant, χ2 (4)=44.59, p<.001. The odds ratio of not yet combining words at age 2, with combining regularly as the referent, was significant (OR=3.141, 95% CI [1.036, 9.527]). PIQ was significant (OR=.945, 95% CI [.917, .974]), as was mother's education, (OR=3.520, 95% CI [1.688, 7.342]). These results suggest that the classification process that resulted in racial differences in the case and control groups was not a primary determinant in the relation of word combining status at age 2 to oral language status at age 8.

Table 5.

Cross-tabulation of age 8 oral language status, age 2 word combining report, and mother's educational attainment for African American participants, with number of participants in each cell.

| Age 8 language | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Mother's education | Word combining at 2? | Typical | Weaka |

| High school or below | Not yet | 6 | 5 |

| Some | 10 | 6 | |

| Often | 11 | 5 | |

| Some college or above | Not yet | 3 | 2 |

| Some | 17 | 2 | |

| Often | 9 | 0 | |

Children with weak oral language at age 8 scored 1 SD or more below the mean on at least 2 of 4 oral language measures, or 2 SD or more below the mean on 1 oral language measure (Cohen et al., 1993).Table 6

3.3. Late talking and academic ability at age 8

We performed a series of analyses to ascertain the relations of late talking with age 8 reading and math skills, and to determine whether the effects of late talking on these skills were mediated by oral language ability.

3.3.1. Word reading

Characteristics of the case (weak word reading) and control groups are summarized in Table 6. The groups did not differ in the proportion of females, but did differ on race, mother's education, and PIQ.

Table 6.

Summary of measures that may covary with language ability for case and control groups formed by word reading, reading comprehension and math ability (weak ability groups scored at or below the 25th percentile on the relevant measure).

| Measure | Weak ability | Typical ability | Test | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word readinga N | 118 | 349 | ||

| Word attack std score M (SD) | 83 (7) | 109 (13) | ||

| Performance IQ M (SD) | 94 (14) | 107 (13) | t (465)=8.9 | .000 |

| Sex % male | 50% | 50% | χ2 (1) = .007 | .936 |

| Mother's ed. ≤ high school | 48% | 32% | χ2 (1) = 10.8 | .001 |

| Race % African American | 31% | 10% | χ2 (4) = 38.2 | .000 |

| Reading comprehensionb N | 44 | 139 | ||

| Psg comp std score M (SD) | 84 (7) | 114 (12) | ||

| Performance IQ M (SD) | 89 (14) | 106 (14) | t (181)=7.2 | .000 |

| Sex % male | 70% | 53% | χ2 (1) = 4.4 | .036 |

| Mother's ed. ≤ high school | 60% | 29% | χ2 (1) = 19.6 | .000 |

| Race % African American | 41% | 12% | χ2 (1) = 19.1 | .000 |

| Broad mathc N | 58 | 181 | ||

| Broad math std score M (SD) | 82 (7) | 120 (14) | ||

| Performance IQ M (SD) | 88 (11) | 106 (15) | t (131)=9.9 | .000 |

| Sex % male | 56% | 53% | χ2 (1) = .26 | .608 |

| Mother's ed.≤high school | 62% | 27% | χ2 (1) = 23.5 | .000 |

| Race % African American | 31% | 12% | χ2 (1) = 12.2 | .000 |

The word reading measure was the Word Attack subtest of the Woodcock–Johnson Psychoeducational Battery, Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1990). Word Attack measured the child's ability to decode word forms.

The reading comprehension measure was the Passage Comprehension subtest of the Woodcock–Johnson Psychoeducational Battery, Revised. Passage Comprehension assessed the ability to correctly provide words to complete sentences about a brief reading passage.

The math ability measure was the Broad Math subtest of the Woodcock–Johnson Psychoeducational Battery, Revised. Broad Math assessed calculation and applied mathematical problem solving

Late talker status based on a restricted vocabulary was entered into a logistic regression predicting weak word reading ability. PIQ, mother's education, and race were entered as controls. The overall model was significant, χ2 (4)=76.66, p<.001. Late talking status was not a reliable predictor after accounting for case and control group differences (OR=1.448, 95% CI [.807, 2.600]). PIQ (OR=.929, 95% CI [.908, .951]) and race contributed to the model (OR=1.939, 95% CI [1.023, 3.678]), whereas mother's education did not (OR=1.125, 95% CI [.664, 1.906]).

Late talker status based on word combining was entered into a similar model predicting word reading ability. The overall model was significant, χ2 (5)=68.75, p<.001. No word combining, when compared to regularly combining words, did not predict age 8 word reading status (OR=1.181, 95% CI [.562, 2.481]). PIQ added to the model's prediction (OR=.930, 95% CI [.908, .952]) but mother's education (OR=1.170, 95% CI [.689, 1.989]) and race (OR=1.695, 95% CI [.864, 3.328]) did not. Late talking, by either criterion, did not predict weak age 8 word reading ability after accounting for case and control group differences.

Given that late talking did not have a direct effect on age 8 word reading ability, a mediation analysis was not performed.

3.3.2. Reading comprehension

Characteristics of the weak reading comprehension (case) and control groups are summarized in Table 6. The groups differed on PIQ, mother's education, sex, and race.

We used logistic regression models to evaluate whether late talking had a direct effect on reading comprehension ability at age 8. The number of control variables and the relatively small sample size indicated a needtoreduce the numberofpredictorstoachieveastable model. After PIQ, mother's education, and sex of the child, race did not significantly contribute to the model (χ2 (1)=1.93, p=.164), and after PIQ and mother's education, sex also did not contribute to model's prediction (χ2 (1)=2.69, p=.101). A final model which included PIQ, mother's education and late talker status based on a restricted vocabulary was significant, χ2 (4)=43.75, p<.001. Late talker status based on a restricted vocabulary was not a significant predictor (OR= 2.443, 95% CI [.904, 6.600]). Late talker status based on word combining had a different result. The overall model was significant, χ2 (4)=43.9, p<.001. No word combinations, when compared to a referent of regularly combining words, was a significant predictor (OR=4.517, 95% CI [1.219, 16.737]). The control variables PIQ (OR=.929, 95% CI [.892, .968]) and mother's education (OR=2.85, 95% CI [1.105, 7.351]) were significant. A child not combining words at age 2 was at significantly more risk of having poor reading comprehension ability at age 8 when compared to peers who were regularly combining words.

Age 8 oral language was then evaluated as a mediator of the effect of not combining words at 2 on age 8 reading comprehension. The linear regression models for the analysis are summarized in Table 7. Based on these models, the indirect effect was estimated at -9.2, (95% CI [-15.6, -2.85]). Age 8 oral language ability was a significant mediator of the effect of age 2 late talker status on age 8 reading comprehension ability.

3.3.3. Math ability

Characteristics of the weak math skills (case) and control groups are summarized in Table 6. Beyond math scores, the groups differed on PIQ, mother's education, and race.

To determine whether late talking was a predictor of later weak math skills, we developed two logistic regression models. We first evaluated control variables for their contribution to the models. After PIQ and mother's education, race did not significantly add to the model's prediction (χ2 (1)=.06, p=.814). A model with PIQ, mother's education, and late talking based on a restricted vocabulary was significant (χ2 (3)=61.08, p<.001). Late talking based on a restricted vocabulary did not significantly add to the model's prediction of math ability (OR=1.958, 95% CI [.825, 4.645]). PIQ (OR=.916, 95% CI [.885, .948]) and mother's education (OR=2.397, 95% CI [1.081, 5.317]) were significant. A model with the same covariates and late talking based on not yet combining words was significant (χ2 (4)= 59.93, p<.001). Word combining status was a significant predictor (OR=3.06, 95% CI [1.075, 8.707]). Children not yet combining words at age 2 were approximately 3 times more likely to have weak math skills at age 8 as compared to children combining words regularly.

The linear regression models evaluating age 8 oral language as a mediator of the effect of late talking (no word combinations) on age 8 math ability are summarized in Table 7. The indirect effect of age 8 oral language was estimated at -9.1 (95% CI [-14.5, -3.75]). Age 8 oral language ability was a significant mediator of the effect of age 2 late talker status (not combining words) on age 8 math ability.

4. Discussion

This study documented the early language emergence histories of children with poor oral language skills at age 8 in order to better understand whether late talking is a meaningful early predictor of poor age 8 oral language and academic ability outcomes. Although outcomes of late talking have been assessed in multiple studies, few studies have looked back to understand whether early language measures would have been reliable early indicators of poor outcomes in middle childhood. The predictive validity of late talking depended on how it was defined.

4.1. Evidence for multiple developmental pathways to language weakness

One major outcome of the study was the finding that many children with significant oral language weakness at age 8 would not have qualified as late talkers at age 2. This finding, which is consistent with recent prospective studies (Henrichs et al., 2011; Reilly et al., 2010), opens the possibility that children may take multiple developmental paths to weak language abilities in middle childhood.

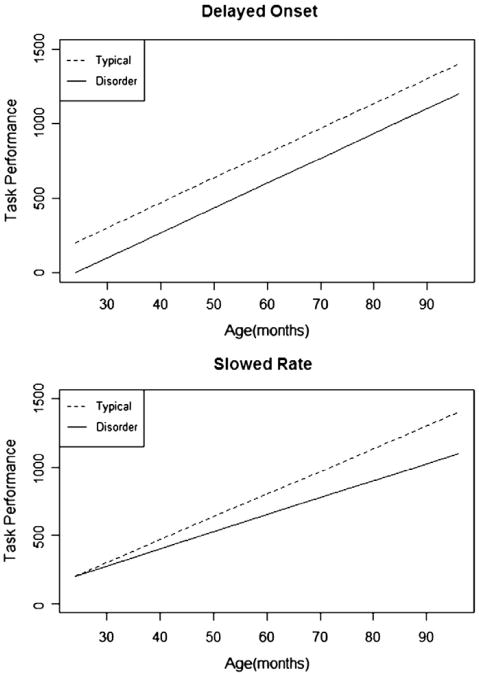

Our findings may be interpreted using the taxonomy of developmental trajectories proposed by Thomas et al. (2009). Two of the proposed trajectories are illustrated in Fig. 1. The pattern of delayed onset appears to be just one possible path for children with weak language at age 8. For the significant portion of children with weak language at age 8 and reported vocabulary or word combining in the typical range at age 2, the slowed rate trajectory appears to be more likely. Whatever the precise shape, their pathways must account for equivalent performance at the early stage and divergence in language skills at a later stage. Clearly there are limitations of the measures available in this study that urge caution in drawing strong conclusions on the specific developmental trajectories for these children. For example, the age 2measures of expressive vocabulary or word combining are not the same as the measures of language ability available at age 8. Nonetheless, the findings do raise the clear possibility that a slowed rate trajectory should be further explored for a subset of children with weak oral language in middle childhood. Possibly, early differences in language comprehension and/or gesture production may help refine predictions of later oral language difficulty (Buschmann et al., 2008; Desmarais, Sylvestre, Meyer, Bairati, & Rouleau, 2010; Thal & Tobias, 1994; Thal, Tobias, & Morrison, 1991).

Fig. 1.

Distinct developmental pathways describing children with weak language abilities at middle childhood. The top graph shows a delayed onset oflanguage, the bottom shows a slowed rate of growth in language ability for the disordered group. Adapted by permission from “Using Developmental Trajectories to Understand Developmental Disorders,” by M.S.C. Thomas, D. Annaz, D. Ansari, G. Scerif, C. Jarrold, and A. Karmiloff-Smith, 2009, Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 52, p. 346. Copyright 2009 by the American Speech Language Hearing Association.

4.2. Covariates of language ability

The process of classifying children with weak oral language abilities in this study resulted in case and control groups that differed by race. This potential bias in the classification process was addressed primarily by statistically controlling for race in the models evaluating the relations of late talking to age 8 language status. The proportions of children with and without a late talking history did not vary by racial group within the weak oral language groups, and an analysis stratified by race suggested that the race differences were not relevant to the primary conclusions regarding late talking history.

Findings of group differences on PIQ and mother's education are consistent with the view that language ability interacts not only with other cognitive abilities, but also with environmental influences throughout development. The fact that word combining status in this study remained a significant predictor of age 8 oral language after accounting for maternal education is consistent with findings from Rice et al. (2008). Rice and colleagues found that for groups with similar socioeconomic backgrounds, late talking was predictive of age 7 oral language weakness. The Rice et al. results suggested that a grammatical knowledge or processing weakness may be more strongly associated with late talking as a risk for later language weakness than skills in other language domains. This may account for the stronger predictive power of the word combining criterion for late talking as compared to the vocabulary limitation criterion in the current study. Vocabulary size may be more associated with socioeconomic factors than the ability to combine language units, consistent with known effects of SES on children's vocabulary (Hart & Risley, 1995).

The lack of association between limited age 2 vocabulary and later language weakness may have been related to the use of PIQ as a covariate in the analyses. If, as is likely, PIQ is deeply intertwined with other abilities, using PIQ as a covariate may increase Type II error (Dennis et al., 2009). It is likely that children with an early restricted vocabulary are at risk for later language weakness, but this language weakness is accompanied by reduced non-verbal cognitive ability. Evidence for this conclusion is the statistically significant unadjusted odds ratios for the association of age 2 vocabulary with age 8 weak oral language (see Appendix A).

4.3. Academic ability and late talking

In the present study, reports of no word combinations at age 2 predicted weak reading comprehension and math abilities at age 8. In contrast, neither late talking criterion predicted weak word attack skills at age 8. The lack of a relationship between late talking and word attack skills is consistent with prior findings (Rescorla, 2005). There has been evidence of a relationship between late talking and reading comprehension ability in middle childhood (Lyytinen, Eklund, & Lyytinen, 2005; Rescorla, 2005), and between contemporary measures of oral language and reading comprehension (Cain & Oakhill, 2006; Catts et al., 2006). What the current study adds is evidence that oral language in middle childhood mediates the relationship of late talking with age 8 reading comprehension. This finding helps to focus efforts to find early predictors of poor language outcomes. Early predictors of weak oral language, if they can be identified, are likely to also be early predictors of a range of academic abilities at middle childhood.

4.4. Limitations

This study identified rates of late talking among children with and without language weaknesses. Two factors limit the generalizability of the findings. First, the NICHD SECCYD excluded children of mothers under 18 and of mothers who did not speak English. As a result, the rates of late and typical talking may not apply to children whose mothers were not adults or English speakers at the child's birth. Second, the MCDI vocabulary norms used in this study were based on a sample of families better educated than is typical of the U.S. population (Fenson et al., 2007). As a result, the rates of late talking based on age 2 vocabulary found in this study likely overestimated the number of late talkers. A methodological limitation of the study is the dichotomization of weak vs. typical language. The creation of categorical variables from continuous data results in a loss of statistical power (Cohen, 1983). Further, more conservative cut-offs for language weakness at age 8 might result in more children being identified as late talkers, but would still leave many children for whom early language did not predict later language.

4.5. Moving toward better early identification

The findings of this study have implications for early identification of children at risk for poor language outcomes. First, findings that age 8 oral language mediates the effects of late talking on academic outcomes underscores the importance of better identifying risk factors for oral language weakness. It is clear from this and other studies that disorders of oral language have broad ramifications on educational ability and attainment (Catts et al., 2002; Young et al., 2002).

A second implication is that criteria for late talking differ in their associations with outcomes at mid-childhood. Delays in word combining appear to contribute to predictions of language ability outcomes beyond differences in SES and non-verbal cognitive ability. An unusually small expressive vocabulary, however, was more prevalent in children with poor language outcomes but not in ways that are easily separable from SES and other cognitive ability differences.

A final implication is that studies with a goal of finding better early indicators of weak oral language need to look beyond late talking. This study suggests that many children at mid-childhood with significant oral language weakness arrived at that point after having early vocabulary and word combining abilities measured in the typical range. This finding leaves open whether children without a late talking history had a different set of causal factors that led to weak language ability. Itis possible that some environmental or cognitive factors played a greater role for these children than they did for children with early measured language delays. Identifying and reliably measuring these factors may significantly aid early identification efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bruce Tomblin and Katharine Donnelly Adams and helpful comments and suggestions for this study. This research was supported by funding from the Center for Language Science at The Pennsylvania State University and by award F31DC010960 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was conducted by the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network supported by NICHD through a cooperative agreement that calls for scientific collaboration between the grantees and the NICHD staff.

Appendix A.

Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) for late talking measures (age 2) as predictors of poor outcomes at age 8—without controlling for weak versus typical group differences in PIQ, race, mother's education, sex.

| Late talker measure | Participants (N) | Unadjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Weak ability | Typical ability | OR | 95% CI | |

| Risk for age 8 weak oral language | ||||

| Vocabulary above 10th percentile (referent) | 46 | 198 | ||

| Vocabulary below 10th percentile | 26 | 43 | 2.6 | [1.5, 4.7] |

| Combining words often (referent) | 27 | 161 | ||

| Not yet combining words | 16 | 18 | 5.3 | [2.4, 11.6] |

| Combining words some | 24 | 60 | 2.4 | [1.3, 4.5] |

| Risk for age 8 weak word reading | ||||

| Vocabulary above 10th percentile (referent) | 73 | 254 | ||

| Vocabulary below 10th percentile | 28 | 52 | 1.9 | [1.1, 3.2] |

| Combining words often (referent) | 46 | 186 | ||

| Not yet combining words | 18 | 35 | 2.1 | [1.1, 4.0] |

| Combining words some | 33 | 81 | 1.6 | [1.0, 2.8] |

| Risk for age 8 weak reading comprehension | ||||

| Vocabulary above 10th percentile (referent) | 22 | 103 | ||

| Vocabulary below 10th percentile | 13 | 22 | 3.6 | [1.5, 8.4] |

| Risk for age 8 poor reading comprehension (continued) | ||||

| Combining words often (referent) | 9 | 79 | ||

| Not yet combining words | 9 | 9 | 8.8 | [2.8, 27.8] |

| Combining sometimes | 14 | 31 | 4.0 | [1.6, 10.1] |

| Risk for age 8 weak math ability | ||||

| Vocabulary above 10th percentile (referent) | 30 | 137 | ||

| Vocabulary below 10th percentile | 17 | 30 | 3.0 | [1.4, 6.2] |

| Combining words often (referent) | 18 | 107 | ||

| Not yet combining words | 13 | 15 | 5.2 | [2.1, 12.6] |

| Combining sometimes | 14 | 38 | 2.2 | [1.0, 4.8] |

Notes. Children with weak oral language at age 8 scored 1 SD or more below the mean on at least 2 of 4 oral language measures,or 2 SD or more below the mean on 1 oral language measure (Cohen, Davine, Horodezky, Lipsett, & Isaacson, 1993). Children with weak academic abilities (word reading, reading comprehension, broad math) scored at the 25th percentile or below on the relevant subtest (Word Attack, Passage Comprehension, Broad Math) of the Woodcock–Johnson Psychoeducational Battery, Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1990).

Contributor Information

Gerard H. Poll, Email: gerard.poll@elmhurst.edu.

Carol A. Miller, Email: cam47@psu.edu.

References

- Buschmann A, Jooss B, Rupp A, Dockter S, Blaschtikowitz H, Heggen I, et al. Children with developmental language delay at 24 months of age: Results of a diagnostic work up. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2008;50:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02034.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain K, Oakhill J. Profiles of children with specific reading comprehension difficulties. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76:683–696. doi: 10.1348/000709905X67610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Adlof SM, Ellis Weismer S. Language deficits in poor comprehenders: A case for the simple view of reading. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:293–298. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Fey ME, Tomblin JB, Zhang X. A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:1142–1157. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/093). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg J, Hollis C, Mawhood L, Rutter M. Developmental language disorders–a follow-up in later adult life. Cognitive, language, and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(2):128–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1983;7:249–253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662168300700301. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, Lipsett L, Isaacson L. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: Prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:595–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti-Ramsden G, Durkin K, Simkin Z, Knox E. Specific language impairment and school outcomes I: Identifying and explaining variability at the end of compulsory education. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2009;44:15–35. doi: 10.1080/13682820801921601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13682820801921601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Francis DJ, Cirino PT, Schachar R, Barnes MA, Fletcher JM. Why IQ is not a covariate in cognitive studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15:331–343. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1355617709090481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais C, Sylvestre A, Meyer F, Bairati I, Rouleau N. Three profiles of language abilities in toddlers with an expressive vocabulary delay: Variations on a theme. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53:699–709. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0245). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0245) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S. Typical talkers, late talkers, and children with specific language impairment: A language endowment spectrum? In: Paul R, editor. Language disorders from a developmental perspective: Essays in honor of Robin S Chapman. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Elman J, Bates EA, Johnson M, Karmiloff-Smith A, Parisi D, Plunkett K. Rethinking innateness: A connectionist perspective on development. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates EA, Hartung JP, et al. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User's guide and technical manual. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Marchman V, Thal D, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E. MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories: Users guide and technical manual. 2nd. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DP, Cooper EB. Prevalence of communication disorders in students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1989;22(1):60–63. doi: 10.1177/002221948902200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley T. Meaningful differences in everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Henrichs J, Rescorla L, Schenk JJ, Schmidt HG, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, et al. Examining continuity of early expressive vocabulary development: The Generation R study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2011;54:854–869. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0255). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopf M. The case control study. International Review of Psychiatry. 1998;10:278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A. Development itself is the key to understanding developmental disorders. Trends in Cognitive Science. 1998;2:389–398. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A. Atypical epigenesis. Developmental Science. 2007;10:84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00568.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon GR. Learning disabilities. The Future of Children: Special Education for Students with Disabilities. 1996;6(1):54–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen P, Eklund K, Lyytinen H. Language development and literacy skills in late-talking toddlers with and without familial risk for dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia. 2005;55:166–192. doi: 10.1007/s11881-005-0010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction tostatistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. The NICHD Study of Early Child Care: A comprehensive longitudinal study of young children's lives. Rockville, MD: Author; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B, Dale PS, Plomin R. Verbal and nonverbal predictors of early language problems: an analysis of twins in early childhood back to infancy. Journal of Child Language. 2004;31:609–631. doi: 10.1017/s0305000904006221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Murray C, Clancy K, Andrews D. Reading and metaphonological outcomes in late talkers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:1037–1047. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4005.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston JL, Frost SJ, Mencl WE, Fulbright RK, Landi N, Grigorenko E, et al. Early and late talkers: School-age language, literacy and neurolinguistic differences. Brain. 2010;133:2185–2195. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S, Wake M, Ukoumunne OC, Bavin E, Prior M, Cini E, et al. Predicting language outcomes at 4 years of age: Findings from early language in Victoria Study. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1530–e1537. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:360–371. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/028). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Age 13 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:459–472. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Taylor CL, Zubrick SR. Language outcomes of 7-year-old children with or without a history of late language emergence at 24 months. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2008;51:394–407. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/029). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development. 2010;81:6–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS. Early identification of children at risk for reading disabilities: Phonological awareness and some other promising predictors. In: Shapiro BK, Accardo PJ, Capute AJ, editors. Specific reading disability: A view of the spectrum. Timonium, MD: York Press; 1998. pp. 75–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Pugh KR, Mencl E, Fulbright RK, Kudlarski P, et al. Disruptions of posterior brain systems for reading in children with developmental dyslexia. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard SE, Snowling MJ, Bishop DVM, Chipchase BB, Kaplan CA. Language-impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41(2):407–418. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4102.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th. Boston: Pearson Education Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thal D, Tobias S. Relationships between language and gesture in normally developing and late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:157–170. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3701.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal D, Tobias S, Morrison D. Language and gesture in late talkers: A 1-year follow-up. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1991;34:604–612. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3403.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MSC, Annaz D, Ansari D, Scerif G, Jarrold C, Karmiloff-Smith A. Using developmental trajectories to understand developmental disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:336–358. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0144). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MSC, Karmiloff-Smith A. Are developmental disorders like cases of adult brain damage? Implications from connectionist modeling. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2002;25:727–788. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle CA, Goldsmith HH, Lemery KS. Genetic, environmental, and gender effects on individual differences in toddler expressive language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:904–912. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/067). http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2004/067) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse AJO, Line EA, Watt HJ, Bishop DVM. Adult psychosocial outcomes of children with specific language impairment, pragmatic language impairment, and autism. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2009;44:511–528. doi: 10.1080/13682820802708098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, Fischel JE. Practitioner review: Early developmental language delay: What, if anything, should the clinician do about it? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:613–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Johnson MB. Woodcock Johnson Psychoeducational Battery —Revised. Allen, TX: DLM Resources; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Beitchman JH, Johnson C, Douglas L, Atkinson L, Escobar M, et al. Young adult academic outcomes in a longitudinal sample of early identified language impaired and control children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):635–645. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]