Abstract

Background and purpose

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SPONK) is a painful lesion in the elderly, frequently leading to osteoarthritis and subsequent knee surgery. We evaluated the natural course and long-term consequences of SPONK in terms of need for major knee surgery.

Methods

Between 1982 and 1988, 40 consecutive patients were diagnosed with SPONK. The short-term outcome has been reported previously (1991). After 1–7 years, 10 patients had a good radiographic outcome and 30 were considered failures, developing osteoarthritis. In 2012, all 40 of the patients were matched with the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) and their medical records were reviewed to evaluate the long-term need for major knee surgery.

Results

At the 2012 review, 33 of the 40 patients had died. The mean follow-up time from diagnosis to surgery, death, or end of study was 9 (1–27) years. 17 of 40 patients had had major knee surgery with either arthroplasty (15) or osteotomy (2). All operated patients but 1 were in the radiographic failure group and had developed osteoarthritis in the study from 1991. 6 of 7 patients with large lesions (> 40% of the AP radiographic view of the condyle) at the time of the diagnosis were operated. None of the 10 patients with a lesion of less than 20% were ever operated.

Interpretation

It appears that the size of the osteonecrotic lesion can be used to predict the outcome. Patients showing early signs of osteoarthritis or with a large osteonecrosis have a high risk of later major knee surgery.

Almost 50 years ago, Ahlbäck and Bauer in Lund—together with the American radiologist Bohne (Ahlbäck et al. 1968)—described a condition that they named spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SPONK). This condition, originally described as a single entity, has been re-classified as 3 separate conditions (Zywiel et al. 2009, Mont et al. 2011, Strauss et al. 2011): (1) SPONK, the subject of the present article, usually affects a single condyle in older patients; (2) the term secondary osteonecrosis is used when the condition has a known cause, such as corticosteroid treatment or sickle-cell anemia. Younger patients are more often affected, and the radiographic appearance is different, with lesions in multiple foci; (3) a third form, osteonecrosis of the knee post arthroscopy, affects only one condyle and starts with increasing knee pain and positive MRI findings after arthroscopic surgery (Kraenzlin et al. 2010).

The etiology of SPONK was—and still is—unknown, but 2 main theories have been advanced: vascular (Kantor 1987, Jones 1993) and traumatic (Yamamoto and Bullough 2000, Akamatsu et al. 2012). SPONK can lead to subchondral collapse and secondary osteoarthritis often requiring knee surgery. The prognosis of the disease has been shown to depend on the size of the lesion (Lotke et al. 1982).

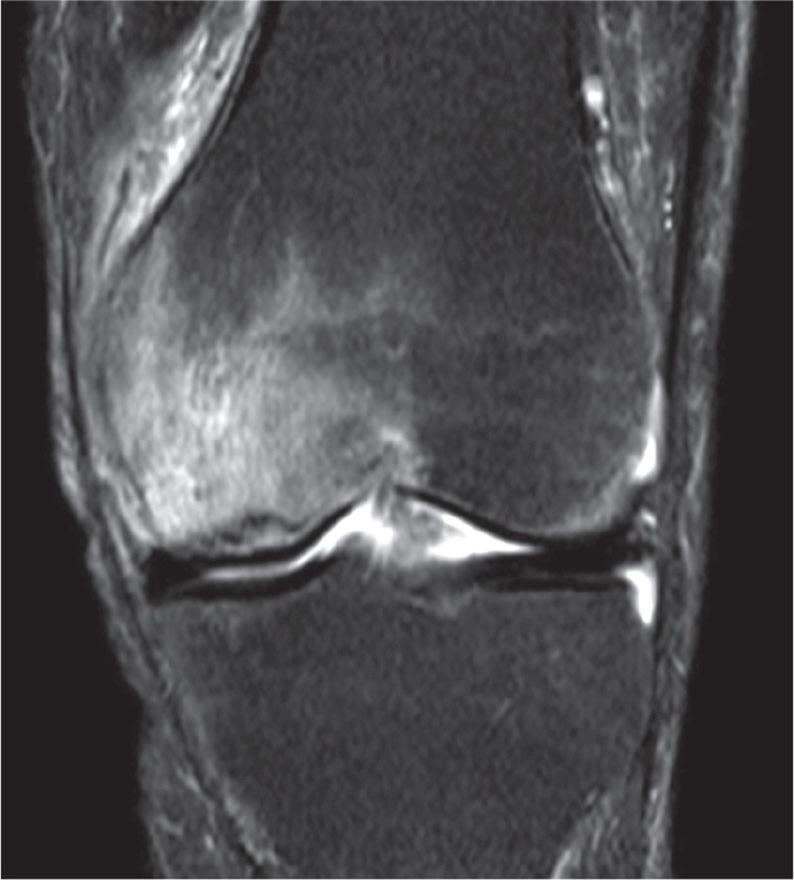

The start of symptoms of SPONK is classically acute onset of pain without predisposing trauma and the most common finding on physical examination is localized tenderness over the medial femoral condyle (Lotke et al. 1982). The initial radiograph may be negative, especially if the symptoms are of short duration, and the diagnosis is therefore often missed at this stage. Later on, radiographs typically show a subchondral radiolucent lesion in the weight-bearing area of the medial or lateral femoral condyle (Figure 1). In some patients, the radiographs may remain normal during the whole course of the disease (Lotke et al. 1977, Houpt et al. 1983) and changes are only seen with bone scintigraphy or magnetic resonance imaging (Koshino 1982). Scintigraphy, performed within a few days of the onset of pain, shows a high uptake in the affected femoral condyle (Rozing et al. 1980). MRI shows bone marrow edema in the affected condyle. This and a focal subchondral lesion (Figure 2) are considered the cardinal signs for diagnosis of osteonecrosis (Björkengren et al. 1990, Yates et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

An 83-year-old woman developed osteonecrosis and secondary osteoarthritis in the medial femur condyle. The initial radiographs at diagnosis (A) and those after 1 year (B) showed a small but typical radiolucent subchondral lesion in the weight-bearing area of the medial femoral condyle. The patient had a total knee arthroplasty 2 years after diagnosis (C).

Figure 2.

MR image showing bone marrow edema of the medial femur condyle with a focal subchondral lesion typical of osteonecrosis.

In a previous study from the orthopedic department of Lund University Hospital, 40 consecutive patients with scintigraphic and/or radiographic signs of osteonecrosis in one of the femoral condyles were followed for 1–7 years (Al-Rowaih et al. 1991). The size of the lesion correlated with the outcome, and lesions equal to or larger than 40% of the involved femoral condyle in the AP radiograph all had a poor outcome, developing osteoarthritis. We reviewed these 40 patients 20 years later to determine the natural course and long-term consequences of untreated SPONK, in terms of need to undergo major knee surgery with high tibial osteotomy or arthroplasty during the rest of their lives.

Patients and methods

The initial study (1982–88)

Between 1982 and 1988, 40 consecutive patients (31 females) were diagnosed with primary osteonecrosis at the orthopedic department of Lund University Hospital, and they were followed for 1–7 years with repeated plain radiography and scintigraphy (Al-Rowaih et al. 1991). The inclusion criteria were (1) rapid onset, (2) a typical localization of pain, and (3) a characteristic positive scintigraphy, and the exclusion criteria were a medical history of a disease known to cause secondary osteonecrosis. Mean age at onset was 67 (41–85) years. During the initial period of the disease, before the diagnosis was confirmed, 3 patients had undergone a medial meniscectomy and 12 patients had received at least 1 intraarticular corticosteroid injection after the onset of symptoms.

AP and lateral radiographs were taken during weight bearing at the initial visit and at the follow-up examinations. The necrotic lesion was staged according to Aglietti et al. (1983). The size of the lesion was measured using 2 methods: (1) by multiplying the width of the lesion in the AP view by the depth in the lateral view (Muheim and Bohne 1970), and (2) by calculating the width of the lesion in the AP view as a percentage of the affected femoral condyle (Lotke et al. 1982). The Ahlbäck classification (1968) was used to stage osteoarthritis if it already existed or was developing.

The duration of symptoms from onset to the first radiographic examination was 34 (2–240) weeks. Radiographic osteonecrotic changes were initally seen in 19 of the 40 knees, and in the remaining patients changes were only seen by scintigraphy. A radiographic osteonecrotic lesion eventually developed in 33 of the 40 knees during the follow-up in 1982–88. 29 patients developed osteoarthritis of Ahlbäck grade 1 or more. 10 patients never developed osteoarthritis during follow-up. 1 patient had persistent pain during 3 years of follow-up but had no osteoarthritis on radiographs, and was operated with arthrotomy and drilling into the osteonecrosis.

The 2012 follow-up

In the present study, carried out in the spring of 2012, all the patients from the initial study were identified and included to determine the incidence of further knee surgery. Information from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) was used to identify patients who had undergone reconstructive knee surgery after the publication of the initial study. The SKAR was started in 1975, and all hospitals performing knee arthroplasties in Sweden report both primary procedures and revision procedures to the SKAR. The coverage of the SKAR is 100% for the hospitals in Sweden, and 97% of Swedish knee arthroplasties have been shown to be included in the register (SKAR 2010). The patients in the original study were matched with the SKAR more than 20 years later, and their medical records were reviewed for additional surgical procedures including high tibial osteotomy.

We used Student’s t-test for statistical analysis of the age differences between groups.

Results

All 40 patients in the original study were identified and their medical journals reviewed. All arthroplasty patients were found in the SKAR, both with the primary surgery and, if applicable, the revision surgery. 33 of the 40 patients had died. 4 unoperated patients were still alive at the most recent follow-up. The mean follow-up time, from diagnosis until death or the end of the study, was 15 (1–30) years. The mean time from diagnosis to one of the 3 endpoints—knee surgery, death, or end of study—was 9 (1–27) years. A Kaplan-Meier failure estimate showing the proportion of patients needing to undergo knee surgery with either osteotomy or arthroplasty over the years was calculated (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier failure estimate showing the proportion of patients requiring knee surgery with arthroplasty or high tibial osteotomy over the years.

17 patients had been operated on with a unicompartmental arthroplasty (n = 6), a total knee arthroplasty (n = 9), or an osteotomy (n = 2) (Table). 1 patient without any radiographic osteoarthritic changes at the initial study later developed osteoarthritis and was operated with a unicompartmental arthroplasty 9 years after onset of symptoms. Except for this patient, all the patients who underwent major surgery were in the “failure” group, developing osteoarthritis in the initial study (1991) with an original Lotke index of ≥ 20. Six of 7 patients with an initial Lotke index of ≥ 40 were eventually operated with a knee prosthesis. None of the the initial study patients in which the lesion was visible only by scintigraphy but not by radiography were ever operated. None of the 10 patients with a lesion of less than 20% were ever operated. The median time to knee surgery was 1.5 (0.5–11) years and 14 out of 17 of the operations were carried out in the first 4 years. However, one patient had surgery 11 years after onset of symptoms (Figure 3).

| Radiographic outcome a |

Arthroplasty 1988 |

Osteotomy 1988 |

Arthroplasty 2012 |

Osteotomy 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good (n = 10) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Failure (n = 30) | 8 | 4 b | 14 | 2 b |

a Radiographic outcome in the initial 1988 study (Al-Rowaih 1991)

b 2 patients who were operated with osteotomy were later revised to arthroplasty.

The mean age of the patients who were operated with knee prosthesis or osteotomy was 68 (48–85) years at the start of symptoms, as compared to 74 (64–84) in the group that had been considered to be failures in the initial study but that had never been operated (p = 0.1). The mean age of the 10 patients with a “good” outcome, who did not develop OA in the initial study, was 56 (41–77) years, as compared to 71 (48–85) years in the group that developed OA (p < 0.001). No gender-related differences could be found regarding the need to undergo surgery with a knee prosthesis.

Discussion

The mean follow-up time from diagnosis to death or end of the study was 15 (1–27) years. Previous studies on SPONK have all had shorter mean follow-up periods, ranging from 2.8 to 5.6 years (Rozing et al. 1980, Lotke et al. 1982, Haupt et al. 1983, Al-Rowaih et al. 1991, Satku et al. 2003). Rozing et al. (1980) reported the largest series, in which 35 of 90 knees with SPONK were treated with osteotomy or arthroplasty.

The size of the lesion has classically been regarded as being prognostic, with an increased risk of osteoarthritis with increasing size (Lotke et al. 1982). In the early follow-up of the present series (Al-Rowaih et al. 1991), a cut-off value could be defined: if 40% of the joint surface was affected in the AP view, the patient developed osteoarthritis. 17 of the 40 patients in the 2012 follow-up had been operated, 15 with arthroplasty and 2 with osteotomy. Patients with a good outcome in the initial 1- to 7-year follow-up continued to do well in this long-term follow-up. Only 1 patient without any radiographic osteoarthritic changes in the initial study deteriorated, and was operated after 9 years. Most surgeries were done during the first years, and if the patient had a small lesion or did not develop OA during this early time period, it appeared less likely that a late deterioration would occur.

Limitations of the study

Bisphosphonates were introduced in clinical practice for the treatment of osteoporosis in the mid- 1990s in Sweden, after the publication by al-Rowaih et al. (1991). No evidence was found in the medical records that any of the patients were treated with bisphosphonates after this, but it cannot be ruled out that some patients may have been treated due to osteoporosis—which might have influenced the outcome. Furthermore, 3 patients had undergone medial meniscectomy before diagnosis of SPONK. Post-arthroscopic osteonecrosis is a rare event, and this entity may have a better prognosis than the primary idiopathic SPONK (Kraenzlin et al. 2010), but it was not described at the time of the initial study. 2 of the 3 patients who had undergone an arthroscopy before the SPONK diagnosis had a good outcome, with no development of osteoarthritis.

Treatment options today involve both non-surgical and surgical methods such as pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMFs) therapy (Marcheggiani et al. 2013), restricted weight bearing, core decompression, osteochondral autograft transfer, and knee artroplasty (Zywiel et al. 2009, Duany et al. 2010, Strauss et al. 2011). No randomized or high-quality studies comparing different treatment options have been published. Systemic treatment with bisphosphonates has been suggested to postpone the resorption of the necrotic bone during the revascularization and new bone formation. Bisphosphonates have delayed the resorption of revascularizing dead bone experimentally (Åstrand and Aspenberg 2002, Little et al. 2003, Tägil et al. 2004, Kim et al. 2005) as well as in clinical hip osteonecrosis case series (Agarwala et al. 2005, Nishii et al. 2006, Ramachandran et al. 2007) and knee osteonecrosis series (Kraenzlin et al. 2010). In the only randomized human study, bisphosphonates in patients with femoral head osteonecrosis substantially reduced the risk of secondary osteoarthritis and hip arthroplasty (Lai et al. 2005). Our group has published a prospective case series of 17 patients with SPONK, in which systemic bisphosponate treatment appeared to reduce the risk of developing severe osteoarthritis compared to the early results of the present series. Only 2 of 17 of these bisphosphonate-treated patients were operated with major knee surgery during the 1- to 4-year follow-up (Juréus et al. 2012), as compared to 12 of 40 in the present untreated series at a similar follow-up time (Al-Rowaih et al. 1991).

In the present series the morbidity of a SPONK was substantial, and treatment to prevent development of osteoarthitis is warranted. Patients with large osteonecrosis (> 40% of the affected condyle) or early signs of osteoarthritis have a high risk of undergoing major knee surgery. At present, these patients should be considered for early major knee surgery but the results of randomized studies with bisphosphonates may change the number of treatment options.

Acknowledgments

JJ: planning, collection and interpretation of data, statistics, and writing the article. AL: project setup, collection and interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. MG: evaluation of imaging studies, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. OR: statistics, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. MT: project setup, planning, collection and interpretation of data, statistics, and writing of the article.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Agarwala S, Jain D, Joshi V, Sule A. Efficacy of alendronate, a bisphosphonate, in the treatment of AVN of the hip. A prospective open-label study . Rheumatology. 2005;44:352–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aglietti P, Insall J, Buzzi R, Deschamps G. Idiopathic osteonecrosis of the knee . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1983;65(5):588–97. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B5.6643563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlbäck S, Bauer GC, Bohne WH. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee . Arthritis Rheum. 1968;11(6):705–33. doi: 10.1002/art.1780110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu Y, Mitsugi N, Hayashi T, Kobayashi H, Saito T. Low bone mineral density is associated with the onset of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(3):249–55. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.684139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rowaih A, Lindstrand A, Björkengren A, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG. Osteonecrosis of the knee. Diagnosis and outcome in 40 patients . Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62(1):19–23. doi: 10.3109/17453679108993085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkengren A, Al-Rowaih A, Lindstrand A, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG, Pettersson H. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: Value of MR imaging in determining prognosis . AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154(2):331–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.2.2105026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duany N, Zywiel M, McGrath M, Siddiqui J, Jones L, Bonutti P, Mont M. Joint preserving surgical treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:11–6. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0872-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houpt J, Pritzker K, Greyson B, Gross A. The natural history of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK): A review . Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1983;13(2):212–27. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(83)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JP. Fat embolism, intravascular coagulation, and osteonecrosis . Clin Orthop. 1993;(292):294–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juréus J, Lindstrand A, Geijer M, Roberts D, Tägil M. Treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SPONK) by a bisphosphonate . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):511–4. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.729184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor H. Bone marrow pressure in osteonecrosis of the femoral condyle (Ahlbäck’s disease) . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;106(6):349–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00456868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Randall TS, Bian H, Jenkins J, Garces A, Bauss F. Ibandronate for prevention of femoral head deformity after ischemic necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis in immature pigs . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87(3):550–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino T. The treatment o spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee by high tibial osteotomy with and without bone-grafting or drilling of the lesion . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1982;64(1):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraenzlin ME, Graf C, Meier C. Possible beneficial effect of bisphosphonate on osteonecrosis of the knee . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:1638–44. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KA, Shen WJ, Yang CY, Shao CJ, Hsu JT, Lin RM. The use of alendronate to prevent early collapse of the femoral head in patients with nontraumatic osteonecrosis. A randomized clinical study . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87(10):2155–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little DG, Peat RA, Mcevoy A, Williams PR, Smith EJ, Baldock PA. Zoledronic acid treatment results in retention of femoral head structure after traumatic osteonecrosis in young Wistar rats . J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(11):2016–22. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotke PA, Ecker ML, Alavi A. Painful knees in older patients . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1977;59:5, 617–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotke PA, Abend JA, Ecker ML. The treatment of osteonecrosis of the medial femoral condyle . Clin Orthop. 1982;(171):109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Grassi A, Setti S, Filardo G, Zambelli L, Bonanzinga T, Rimondi E, Busacca M, Zaffagnini S. Conservative treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee in the early stage: Pulsed elecromagnetic fields therapi . Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(3):530–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.11.011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.11.011. Epub 2012 Dec 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mont MA, Marker DR, Zywiel MG, Carrino JA. Osteonecrosis of the knee and related conditions . J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(8):482–94. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muheim G, Bohne W. Prognosis in spontaneos osteonecrosis of the knee . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1970;56(4):605–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishii T, Sugano N, Miki H, Hashimoto J, Yoshikawa H. Does alendronate prevent collapse in osteonecrosis of the femoral head? . Clin Orthop. 2006;443:273–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194078.32776.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran M, Ward K, Brown RR, Munns CF, Cowell CT, Little DG. Intravenous bisphosphonate therapy for traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head in adolescents . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(8):1727–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing P, Insall J, Bohne W. Spontaneous osteonecrisis of the knee . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1980;61(1):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satku K, Kumar VP, Chong SM, Thambyah A. The natural history of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the medial tibial plateau . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003;85(7):983–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b7.14580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Kang R, Bush-Joseph C, Bach B. The diagnosis and management of spontaneous and post-arthroscopy osteonecrosis of the knee . Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(4):320–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tägil M, Astrand J, Westman L, Aspenberg P. Alendronate prevents collapse in mechanically loaded osteochondral grafts: a bone chamber study in rats . Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(6):756–61. doi: 10.1080/00016470410004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Bullough PG. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: the result of subchondral insufficiency fracture . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000;82(6):858–66. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200006000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates P, Calder J, Stranks G, Conn K, Peppercorn D, Thomas N, Early MRI diagnosis and non-surgical management of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. . The Knee. 2007;14:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiel M, McGrath M, Seyler T. Osteonecrosis of the knee: A review of three disorders . Orthop Clin N Am. 2009;40:193–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åstrand J, Aspenberg P. Systemic alendronate prevents resorption of necrotic bone during revascularization. A bone chamber study in rats . BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2002;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]