Abstract

Background and purpose

— Dupuytren’s disease (DD) is a benign fibroproliferative process that affects the palmar fascia. The pathology of DD shows similarities with wound healing and tumor growth; hypoxia and angiogenesis play important roles in both. We investigated the role of angiogenic proteins in DD.

Patients and methods

— The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), its receptors vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), hypoxia-inducible factor alfa (HIF-1α), and alfa-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) were analyzed immunohistochemically in fragments of excised Dupuytren’s tissue from 32 patients. We compared these values to values for expression in a control group.

Results

— 15 of 32 samples could be attributed to the involutional phase (α-SMA positive), whereas 17 samples were considered to be cords at the residual phase (α-SMA negative). In the involutional phase, the HIF-1α and VEGFR2 expression was statistically significantly higher than in the residual phase and in the controls.

Interpretation

— Both the VEGFR2 receptor and HIF-1α were expressed in α-SMA positive myofibroblast-rich nodules with characteristics of DD in the active involutional phase. Thus, hypoxia and (subsequently) angiogenesis may have a role in the pathophysiology of DD.

Dupuytren’s disease (DD) is a benign progressive disease of the palmar aponeurosis that leads to permanent and irreversible flexion contracture of the fingers because of an increased deposition of collagen (Rayan 2007, Shih and Bayat 2010).

Since the first description of the disease centuries ago, the etiology of DD has been debated. Various genetic aberrations have been linked to development of DD (Dolmans et al. 2011). Also, environmental factors such as manual work, smoking, and alcohol—and diseases such as diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection—are known to be associated with DD. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that synthesize collagen have been attributed a central role in the disease. One proposed hypothesis for the pathogenesis is that local tissue damage (and hypoxic conditions) caused by the above factors lead to myofibroblast proliferation or tissue repair (Al-Qattan 2006, Shih and Bayat 2010).

Myofibroblasts have been analyzed at different stages of the disease (Tomasek et al. 2002, Verjee et al. 2009). 3 distinct histological phases have been defined that describe the disease progression: (1) proliferative, (2) involutional, and (3) residual. The lesion in the proliferative phase is almost entirely composed of myofibroblasts in highly cellular nodules. In the involutional phase, which is still highly cellular, cells begin to align themselves along the lines of stress within the tissue. In the residual phase, which is almost acellular, myofibroblasts disappear, leaving mature fibroblasts combined with bundles of collagen (Luck 1959). Interestingly, an increased ratio of collagen III to collagen I has been detected in the involutional phase, which is uncommon with fasciae under physiological conditions (Brickley-Parsons et al. 1981, Shih and Bayat 2010).

Myofibroblasts are also present in wound healing, and they play an important role throughout the healing process, eventually causing a large deposit of collagen III (Burge et al. 1997). Thus, parallels have been drawn between DD and wound healing (Fitzgerald et al. 1999, Tomasek et al. 2002, Howard et al. 2004, Shih and Bayat 2010, Holzer and Holzer 2011).

At the molecular level, several growth factors have been detected in DD, such as transforming growth factor alfa and beta isoforms, platelet-derived growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, nerve growth factor, and epidermal growth factor or its receptors (Gonzalez et al. 1992, Baird et al. 1993, Badalamente et al. 1996, Pagnotta et al. 2002, Augoff et al. 2005). These factors have also been shown to be involved in physiological processes such as wound healing and pathologic processes such as fibrosis or tumor growth.

Hypoxia activates the transcription of hypoxia-inducible factor alfa (HIF-1α) (Ke and Costa 2006). HIF-1α binds to the hypoxia response element in the gene promoter region of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene, which in turn upregulates VEGF expression. As the major angiogenic growth factor, VEGF stimulates endothelial cells to migrate, proliferate, and form countless new capillaries. These new capillaries invade the provisional wound matrix, which consists of immature collagen (type III), proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, fibrin, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid, in which matrix fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, leucocytes, and macrophages are embedded. Transgenic mice with overexpression of VEGF show enhanced wound healing of the skin (Elson et al. 2000).

Recent studies have suggested that HIF activation promotes (renal) fibrogenesis. The spectrum of HIF-activated biological responses to hypoxic stress may differ under conditions of acute and chronic hypoxia (Haase 2009).

Angiogenesis is an important component of many physiological processes such as growth and differentiation of tissues and reparative processes (e.g. wound healing and fracture healing) (Folkman 2006). Pathological angiogenesis (also called neoangiogenesis) most commonly occurs in ischemic, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases (Folkman 2006). VEGF is a glycoprotein that plays an important role in tumor angiogenesis. It binds itself to 2 related receptor tyrosine kinases, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1, also known as FLT1) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2, also known as KDR or Flk1) (Ferrara et al. 2003).

As previously described, hypoxic conditions and subsequent angiogenesis are fundamental processes in wound healing or tumor growth, and they are important stimulators of fibrosis in several tissues. Thus, our aim was to examine the expression of VEGF and its receptors (VEGFR1, VEGFR2) and HIF-1α in Dupuytren’s tissue to test the hypothesis that hypoxia and/or angiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of DD.

Patients and methods

32 caucasian patients with DD (mean age 57 (33–81) years, 26 males) who were surgically treated between April and December 2008 were included in the study (Table 1). DD was diagnosed according to Iselin’s 4-degree classification (Iselin and Dieckmann 1951, Augoff et al. 2005). Although the clinical symptoms and the grade of contracture were used as surgical indications, there was a distribution over all the clinical Iselin stages.

Table 1.

Demographic data from patients with DD and carpal tunnel syndrome

| Dupuytren’s disease | Carpal tunnel syndrome |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Involutional phase |

Residual phase |

||

| No. | 15 | 17 | 9 |

| Sex | |||

| Female/Male | 2/13 | 3/13 | 6/3 |

| Mean age (SD), years | 54 (11) | 61 (12) | 62 (10) |

| (range) | (33–71) | (39–81) | (44–79) |

| Iselin classification | |||

| Stage I | 3/15 | 3/17 | |

| Stage II | 3/15 | 5/17 | |

| Stage III | 6/15 | 7/17 | |

| Stage IV | 3/15 | 2/17 | |

Patients had either partial or total fasciectomy, and samples of pathological palmar aponeurosis (Dupuytren’s tissue) were taken during surgery, quick-frozen in Tissue-Tek Cryomold Standard (Miles Laboratories Inc., Kankakee, IL) and stored frozen at –70°C. Tissue from 9 patients (mean age 62 (44–79) years, 6 females) who were surgically treated for carpal tunnel syndrome served as the controls.

The samples were classified histologically according to the 3 distinct phases proposed by Luck (1959): (1) proliferative, (2) involutional, and (3) residual.

To establish the myofibroblast phenotype and the relationship between VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and HIF-1α localization, we obtained representative serial sections of diseased and control tissues to probe for alfa-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a myofibroblast phenotypic marker 5 µg/mL anti-mouse α-SMA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (Catalog no. A 2547).

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen tissue specimens were cut into 5-µm thick sections and placed on lysine-coated slides. Before immunostaining (using the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase staining method), the slides were dried for 30 min at room temperature and then fixed in acetone for 10 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was eliminated by incubation in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 3 min.

The sections were then incubated with the following antibodies: anti-VEGF (0.4 µg/ml, goat IgG, catalog no. sc-152; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), anti-VEGFR1 (0.1 µg/mL, goat IgG, catalog no. AF321; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-VEGFR2 (1 µg/mL, mouse IgG, catalog no. sc-6251; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-HIF-1α (2 µg/mL, mouse monoclonal IgG, catalog no. sc-53546; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The same immunohistochemical protocol was followed for the negative controls, with omission of the primary antibodies. Blood vessels at the periphery of the tissue samples were used as internal positive controls.

After incubation with the primary antibodies, the sections were incubated with biotin-labeled rabbit anti-mouse antibody followed by streptavidin at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction products were developed with 0.5% Triton X 100 (SERVA) and 10 µL hydrogen peroxide per 100 mL of staining fluid and 0.06% diaminobenzidine (Fluka, Buchs, CH). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

The staining intensity of the immunohistochemically stained sections was evaluated semiquantitatively. A zero score defined slides with no staining, while 1+ referred to slides with a faint staining. A weakly positive result characterized by weak staining was represented by a 2+ score, while a strongly positive result was represented as 3+. Scores of 0 were classified as negative, while scores of 1+, 2+, and 3+ were regarded as positive.

Ethics

The representative material and patient demographic data were collected after obtaining informed consent. In all cases, acquisition of samples complied with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 183/2008).

Statistics

All data are given as mean (range). Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test, and p-values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Histologically, 15 samples were attributed to the involutional phase of the disease and 17 samples were attributed to the residual phase, according to Luck’s classification. α-SMA positive samples were considered to be myofibroblast-rich palmar nodules characteristic of Dupuytren’s tissue. Cellular-rich nodules mainly composed of myofibroblasts could be seen by positive staining for α-SMA in 15 of 32 samples, whereas 17 samples were considered to be lesions at the residual phase (Figure 1). All the control samples were negative for α-SMA expression.

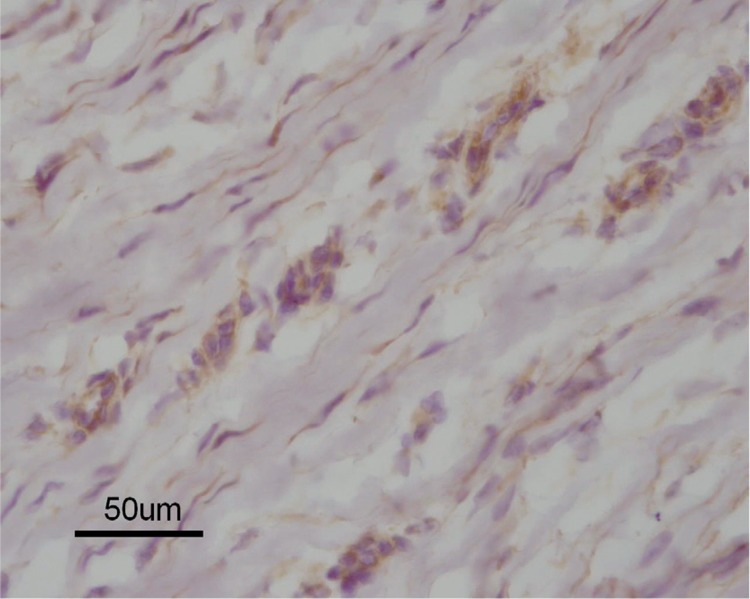

Figure 1.

A. Alfa-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts at the involutional (nodule) phase (magnification 400×). B. Immunohistochemically negative differentiated fibroblasts at the residual (cord) phase of DD (magnification 400×).

Iselin’s clinical classification did not correlate with the histological results (according to Luck) for either the involutional phase or the residual phase of the disease.

Immunohistochemical staining

In 9 of 15 samples from the involutional phase, at least one of the proteins was expressed (as compared to 4 of 17 samples from the residual phase). HIF-1α expression was positive in 6 of 15 samples at the involutional phase; VEGFR1 expression was positive in 4 of 15 cases and VEGFR2 expression was positive in 5 of 15 cases, whereas VEGF expression was low (2 of 15). VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and HIF-1α were not expressed in the control samples, but VEGF was expressed in 2 of 9 control samples (Table 2 and Figures 2–5).

Table 2.

Number of α-SMA positive, α-SMA negative, and control cases that expressed VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and HIF1-α

| n | VEGF | VEGFR1 | VEGFR2 | HIF-1α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involutional phase a | 15 | 2/15 | 4/15 d | 5/15 d, c | 6/15 c, f |

| Residual phase b | 17 | 3/17 | 4/17 | 1/17 e | 2/17 f |

| Controls | 9 | 2/9 | 0/9 d | 0/9 d | 0/9 c |

a α-SMA positive

b α-SMA negative

c statistically significant compared to the controls (p < 0.05).

d statistical trend compared to the controls (p < 0.1).

e statistically significant compared to Luck’s involutional and residual

phases (p < 0.05).

f statistical trend compared to Luck’s involutional and residual

phases (p < 0.1).

Figure 2.

VEGF is expressed in the cytoplasm of cells during different phases of cell maturity. Note the collagen fibers around the fibroblasts, which are characteristic of the involutional phase of DD (magnification 400×).

Figure 3.

Only the discrete foci of VEGFR1-positive cells surrounded with collagen fibers were observed in the DD tissue samples from the involutional phase (magnification 400×).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of DD tissue samples at the involutional phase showing VEGFR2 expression in the remaining myofibroblasts, and also in more mature fibroblasts (magnification 400×).

Figure 5.

HIF1α-positive cells in the foci of the involutional phase of DD. The mature fibroblasts surrounded by collagen matrix were histologically negative (magnification 400×).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to determine the expression of VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and HIF-1α in tissue specimens of DD and to compare the expression with the clinical features of the disease. In the majority of samples from the involutional phase, at least one of the proteins was expressed; but only 4 samples at the residual phase showed some weak staining. VEGF, its receptors (VEGFR1 and VEGFR2), and also HIF-1α showed expression in a higher proportion of samples at the involutional phase than samples at the residual phase. Tissue with positive staining for α-SMA (indicating myofibroblast-rich nodules) was found to express VEGFR2 and HIF-1α at a statistically significant level, indicating a trend in the expression of VEGFR1.

Surgical indications in this patient group were based on clinical symptoms. There was a wide distribution of patients according to Iselin’s classification (see Table 1), although most were stage III and IV because of the severity of cases. There was no correlation between protein expression and clinical stage of DD according to Iselin’s classification. In this respect, a clinical classification such as Iselin’s does not seem appropriate.

DD has been compared with wound healing, for several reasons. Dupuytren’s tissue and granulation tissue formed in healing wounds show similarities in cell types, proliferation, vascularity, and collagen morphology (Fitzgerald et al. 1999). The proliferation of contractile cells (fibroblastic cells in DD) is similar to the fibroblast proliferation in wound healing, and the ratio of collagen type III to collagen type I is increased in both processes.

Angiogenic proteins and HIF-1α have been shown to be involved in various proliferative or regenerative processes. Hypoxic conditions trigger HIF and (subsequently) VEGF and its receptors, which are important in various fibrotic conditions (Ferrara et al. 2003, Folkman 2006).

Wound healing is a complex process in which angiogenesis plays a vital role. It requires a regulated interaction between endothelial cells, soluble angiogenic growth factors, and the extracellular matrix (Eming et al. 2007). Interactions between endothelial cells and vascular cells (perivascular cells/vascular smooth muscle cells) have recently attracted interest. VEGF and its receptors appear to be key mediators in embryonic vascular development and physiological and pathological angiogenesis in adults (Ferrara et al. 2003, Kerbel 2008), but their specific function in wound angiogenesis has not been elucidated. HIF-1α is considered to be the major coordinator of the cellular adaptive response to hypoxia (Ke and Costa 2006). HIF-1α transcriptional products (VEGF and others) have been shown to regulate the process of endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell survival, and migration. Reduced HIF-1α levels and activity have been documented in conditions of impaired wound healing (in the elderly and in diabetics). Angiogenesis may play a role in the pathophysiology of DD by activating the fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that synthesize collagen.

Tissue is distributed inhomogeneously within Dupuytren’s cords. Two-thirds of the cords showed areas with myofibroblast-rich nodules (Verjee et al. 2009). These areas can be considered active and be attributed to the involutional phase, whereas tissue with bundles of collagen and fibroblasts characterize the inactive residual phase. Active and inactive areas within the DD are described as nodules and cords, respectively. In this study, 17 of 32 specimens could be attributed to the residual phase and 15 to the involutional phase. At the involutional phase, a clear staining of α-SMA was observed in all specimens. In that phase, there was a higher expression of VEGFR2 (statistically significant compared to the residual phase), HIF-1α (statistically significant compared to the controls and higher—although not statistically significantly so—than at the residual phase) and VEGFR1 (higher—although not statistically significantly so—than in the controls). These results indicate that there is participation of HIF-1α and VEGFR2 in the myofibroblast-rich nodules as active DD processes, whereas expression of VEGF and VEGFR1 is low and is more likely at an advanced histological stage.

There has been much discussion about the most appropriate treatment option for DD. For decades, fasciectomy (partial or total) was the standard treatment procedure; the recent introduction of collagenase injections offered a non-surgical option with good short-term results (Hurst et al. 2009). The high recurrence rate is known to be the most important issue in treating DD (Rayan 2007, Holzer and Holzer 2009). Recently published results, which are supported by this study, have indicated that one of the reasons for this high recurrence might be the ineffective treatment of the active myofibroblast-rich nodules (Verjee et al. 2009].

Our findings might justify consideration of introducing pre-surgical examinations that could locate the α-SMA positive myofibroblast-rich nodules with a view to considering these areas as target points for surgery. Magnetic tomography or scintigraphy would be possible approaches. If the α-SMA positive myofibroblast-rich nodules can be located, inhibitors of HIF-1α and VEGF (or its receptors) might be an option to inhibit the activity of myofibroblast nodules.

Acknowledgments

LAH designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. AC analyzed the immunohistochemistry and wrote some of the manuscript. GP performed the surgeries and wrote some of the manuscript. GH designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

None of the authors received funding for this study. We thank the staff of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the Klinikum Klagenfurt am Wörthersee for their assistance in collecting specimens.

LAH and GH would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Attila Nyary (1929–2011).

No competing interests declared.

References

- Al-Qattan MM. Factors in the pathogenesis of Dupuytren’s contracture . J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(9):1527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augoff K, Kula J, Gosk J, Rutowski R. Epidermal growth factor in Dupuytren’s disease . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Sampson SP, Hurst LC, Dowd A, Miyasaka K. The role of transforming growth factor β in Dupuytren’s disease . J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(2):210–5. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80102-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird KS, Crossan JF, Ralston SH. Abnormal growth factor and cytokine expression in Dupuytren’s contracture . J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(5):425–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley-Parsons D, Glimcher MJ, Smith RJ, Albin R, Adams JP. Biochemical changes in the collagen of the palmar fascia in patients with Dupuytren’s disease . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1981;63(5):787–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge P, Hoy G, Regan P, Milne R. Smoking, alcohol and the risk of Dupuytren’s contracture . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1997;79(2):206–10. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b2.6990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmans GH, Werker PM, Hennies HC, Furniss D, Festen EA, Franke L, Becker K, van der Vlies P, Wolffenbuttel BH, Tinschert S, Toliat MR, Nothnagel M, Franke A, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, Nürnberg P, Giele H, Ophoff RA, Wijmenga C. Wnt signaling and Dupuytren’s disease . N Engl J Med. 2011;365(4):307–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson DA, Ryan HE, Snow JW, Johnson R, Arbeit JM. Coordinate up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 alpha and HIF-1 target genes during multi-stage epidermal carcinogenesis and wound healing . Cancer Res. 2000;60(21):6189–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, Koch M. Regulation of angiogenesis: wound healing as a model . Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2007;42(3):115–70. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J, The biology of VEGF and its receptors . Nat Med. 2003;9(6):669–76. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald AM, Kirkpatrick JJ, Naylor IL. Dupuytren’s disease. The way forward? . J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24:4, 395–9. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis . Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez AM, Buscaglia M, Fox R, Isacchi A, Sarmientos P, Farris J, Ong M, Martineau D, Lappi DA, Baird A. Basic fibroblast growth factor in Dupuytren’s contracture . Am J Pathol. 1992;141(1):661–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH, Pathophysiological consequences of HIF activation: HIF as a modulator of fibrosis . Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1177:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer LA, Holzer G. Injectable collagenase clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture . N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer LA, Holzer G. Collagenase clostridum histolyticum in the management of Dupuytren’s contracture . Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2011;43(5):269–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard JC, Varallo VM, Ross DC, Faber KJ, Roth JH, Seney S, Gan BS. Wound healing-associated proteins Hsp47 and fibronectin are elevated in Dupuytren’s contracture . J Surg Res. 2004;117(2):232–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LC, Badalamente MA, Hentz VR, Hotchkiss RN, Kaplan FT, Meals RA, Smith TM, Rodzvilla J, CORD I. Study Group. Injectable collagenase clostridium histolyticum for Dupuytren’s contracture . N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):968–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iselin M, Dieckmann GD. Therapy of Dupuytren’s contracture with total zigzag plastic surgery . Presse Med. 1951;59(67):1394–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) . Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(5):1469–80. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis . N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck JV. Dupuytren’s contracture; a new concept of the pathogenesis correlated with surgical management . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1959;41:4, 635–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnotta A, Specchia N, Greco F. Androgen receptors in Dupuytren’s contracture . J Orthop Res. 2002;20(1):163–8. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayan GM. Dupuytren disease: Anatomy, pathology, presentation, and treatment . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89:1, 189–98. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200701000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih B, Bayat A. Scientific understanding and clinical management of Dupuytren disease . Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:12, 715–26. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling . Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(5):349–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verjee LS, Midwood K, Davidson D, Essex D, Sandison A, Nanchahal J. Myofibroblast distribution in Dupuytren’s cords: correlation with digital contracture . J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(10):1785–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]