Abstract

Background and purpose

— Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a heritable disorder of connective tissue caused by a defect in collagen type I synthesis. For bone, this includes fragility, low bone mass, and progressive skeletal deformities, which can result in various degrees of short stature. The purpose of this study was to investigate development of bone mineral density in children with OI.

Patients and methods

— Development of lumbar bone mineral density was studied retrospectively in a cohort of 74 children with OI. Mean age was 16.3 years (SD 4.3). In 52 children, repeated measurements were available. Mean age at the start of measurement was 8.8 years (SD 4.1), and mean follow-up was 9 years (SD 2.7). A longitudinal data analysis was performed. In the total cohort (74 children), a cross-sectional analysis was performed with the latest-measured BMD. Age at the latest BMD measurement was almost equal for girls and boys: 17.4 and 17.7 years respectively.

Result

— Mean annual increase in BMD in the 52 children was 0.038 g/cm2/year (SD 0.024). Annual increase in BMD was statistically significantly higher in girls, in both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis. In cross-sectional analysis, in the whole cohort the latest-measured lumbar BMD was significantly higher in girls, in the children with OI of type I, in walkers, and in those who were older, in both unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

Interpretation

— During 9 years of follow-up, there appeared to be an increase in bone mineral density, which was most pronounced in girls. One possible explanation might be a later growth spurt and older age at peak bone mass in boys.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a heritable disorder of connective tissue caused by a defect in collagen type I synthesis. The Sillence classification subdivides OI patients according to clinical, radiographic, and genetic characteristics (Sillence et al. 1979). Dominant mutations in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes located on chromosomes 7 and 17 lead to defects in the pro-α1 and pro-α2 chains of collagen I. In autosomal recessive OI, mutations in other genes have been found (van Brussel et al. 2011, van Dijk et al. 2012). Clinically, OI shows a highly variable expression in all tissues affected. For bone this includes fragility, low bone mass, and progressive skeletal deformities, resulting in various degrees of short stature.

The natural accrual of OI bone during childhood has not been studied extensively. Optimal skeletal development in childhood remains one of the cornerstones for attainment of optimal skeletal health (Schonau 2004). This idea is based on the observation that bone density increases with growth during childhood, is highest post adolescence, and declines by the time the individual reaches his/her mid-thirties (Boot et al. 2010). Bone strength in later life largely depends on peak bone mass. Children with OI are prone to relative bone loss during growth, with impairment of bone accrual and peak bone mass ( Zionts et al. 1995, van der Sluis and Muinck Keizer-Schrama 2001). Osteoporosis management in childhood is therefore important, and should concentrate on altering the most detrimental part of bone disease, i.e. bone resorption (Baroncelli et al. 2005).

Since the 1990s, bisphosphonates have been used successfully in OI (Glorieux et al. 1998, Astrom and Soderhall 2002, Sakkers et al. 2004). In well-controlled studies, it has been shown that by using bisphosphonates in children with OI, mineralized bone tissue and bone strength will increase (Glorieux et al. 1998, Sakkers et al. 2004, Letocha et al. 2005, Ward et al. 2011). Moreover, histomorphometric studies after bisphosphonate treatment have shown an increase in cortical thickness and in the number of trabeculae (Rauch et al. 2002).

The increase in mineralized bone during growth can be studied by using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). To date, however, only a small number of longitudinal studies on OI have been published regarding bone mineral density (BMD) during growth (Zionts et al. 1995, Reinus et al. 1998, Lund et al. 1999, Cepollaro et al. 1999, Castillo and Samson-Fang, 2009). However, these longitudinal studies have been limited by small sample sizes and by being descriptive. In this longitudinal observational study, we investigated development of bone mass in a large cohort of children with OI. We investigated whether there was a correlation between clinical factors and annual increase in lumbar BMD or latest-measured lumbar BMD.

Patients and methods

The initial cohort consisted of 74 children with OI (39 girls) who were seen consecutively beween 1997 and 1999 at Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center, Utrecht. This is a tertiary referral center for children with OI in the Netherlands. The diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta was based on clinical history and radiographic features. When in doubt, a genetic investigation was performed (van Dijk et al. 2012). Data were collected in the outpatient clinic by a single research physician trained in examining children with OI. All patients had at least 1 BMD measurement of the lumbar spine during this period.

In 52 of the 74 children with OI (28 girls), a longitudinal study could be performed. At baseline, the following independent variables were included: age, sex, bisphosphonate use, OI type, and ambulation level. Information about onset of puberty, pubertal stage, BMI, and bone age was not taken into account because these data were incomplete in many children. Fracture history was not taken into account. Fracture treatment philosophy evolved during the 9 years of follow-up and was not therefore a consistent item for use in analysis. OI type was classified according to Sillence et al. (1979), which is a classification based on clinical, radiographic, and genetic characteristics. Ambulation level was assessed using the modified criteria of Bleck (Engelbert et al. 1997). The Bleck score distinguishes 7 ambulation categories, category 1 being a non-walker and 7 being a community walker without crutches. The Bleck score was registered at the latest DEXA measurement, in the whole cohort. Bisphosphonate use was defined as previous or current use of oral or intravenous bisphosphonate, irrespective of dosage or duration. Calcium or vitamin D intake was not taken into account, because our pediatricians consider that a Dutch diet contains sufficient calcium, and in winter all Dutch children are encouraged to use vitamin D supplementation (Weggemans et al. 2009).

Follow-up BMD measurements were retrospectively collected during the period November 2008 through January 2011. 2 measurements from 2 patients were obtained from other hospitals.

Height and weight were measured with standardized equipment. BMD of the lumbar spine was measured by DEXA (Hologic ADR 4500). A single trained laboratory technician performed all BMD measurements over the entire study period. Intraobserver variation showed no significant drift over time.

Statistics

To determine the development of BMD, we performed 2 different analyses with BMD as a dependent variable. In the first analysis, the annual increase in BMD was taken as the dependent variable. A non-standardized regression coefficient (beta BMD) was therefore estimated for each of the 52 patients who had at least 2 BMD measurements. The value of this regression coefficient expresses the annual increase in BMD for each individual patient. Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression analysis was performed to determine the influence of sex, OI type, bisphosphonate use, and ambulation level on annual increase in BMD.

In the second, cross-sectional analysis (n = 74), the latest-measured BMD in the above-mentioned group was used together with the BMD values of 22 remaining children who had undergone a single BMD measurement. The latest- or single-measured BMD during this observational period from all 74 patients was taken as the dependent variable. We selected the latest measurement instead of the first measurement in the 52 patients with multiple measurements, to investigate a possible retrospective effect of known determinants, such as ambulation. Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression analysis was performed to determine the influence of sex, OI type, bisphosphonate use, and ambulation level on latest-measured BMD.

For statistical as well as clinical reasons, ambulation level (Bleck score) was dichotomized into walker and non-walker, Bleck score 1 to 6, was classifiaed as non-walker, which ranges from non-walking to walking in the neighbourhood with crutches. Bleck score 7 was classified as walker. Non-walker meant unable to walk at the time of the latest DEXA; previous walking history was not taken into account. OI type was dichotomized into severe (types III and IV) and mild (type I). In order to adjust for the age differences at baseline, we included age at the first BMD measurement in the regression analysis. Means (SD) were calculated for continuous variables and proportions were measured for discrete variables. Odds ratios were expressed with 95% confidence intervals. In statistical analyses, p-values of < 0.05 were considered significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0.

Results

52 Of the original 74 patients had at least 2 BMD measurements during the study period. The maximum number of repeated BMD measurements was 8. In 22 patients, only a single spinal BMD measurement was available due to surgery of the lumbar spine (spondylodesis, n = 10) and loss to follow-up (n = 12). These children were not included in the longitudinal analysis.

Baseline characteristics of the 52 children included in the longitudinal data analysis are listed in Table 1. In the longitudinal data analysis, mean follow-up was 9 years (SD 2.7). Lumbar BMD in these children with OI increased by 0.34 g/cm2 during the 9 years of follow-up. The mean increase in BMD during this 9-year follow-up was higher in girls: 0.37 g/cm2 as compared to 0.25 g/cm2 in boys. The mean annual increase in BMD in these 52 children was 0.038 g/cm2/year (SD 0.024). Annual increase in BMD was significantly higher for girls in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Other parameters investigated were not associated with annual increase in BMD (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 52 OI patients in the longitudinal analysis

| Age at first DEXA (mean, SD), years | 8.6 (4.1) |

| Age at latest DEXA (mean, SD), years | 17.5 (3.9) |

| Male : Female, % | 46 : 54 |

| OI type I : III/IV, % | 59 : 41 |

| Bleck score; walker : non-walker, % | 48 : 52 |

| Bisphosphonate use; yes : no, % | 69 : 31 |

DEXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry;

OI: osteogenesis imperfecta.

Table 2.

Factors associated with annual increase in BMD in 52 patients with OI

| Beta BMD (g/cm2) | Unadjusted (CI) | p-value | Adjusted(CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex a | –0.016 (–0.031 to 0.000) | 0.05 | –0.020 (–0.036 to –0.003) | 0.02 |

| Bisphosphonate use | 0.009 (–0.009 to 0.026) | 0.3 | 0.013 (–0.005 to 0.032) | 0.2 |

| Walker/non-walker | 0.000 (–0.016 to 0.016) | 0.99 | –0.008 (–0.029 to 0.014) | 0.5 |

| OI type I : III/IV | 0.003 (–0.014 to 0.019) | 0.7 | 0.007 (–0.017 to 0.030) | 0.6 |

| Age at start | 0.000 (–0.002 to 0.002) | 0.8 | 0.000 (–0.002 to 0.003) | 0.7 |

a Significant association with annual increase in BMD in unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

Reference categories: female sex, no bisphosphonate use, walker, OI of type I.

Regression coefficient is calculated for 1-year increment in age at start.

BMD: bone mineral density; OI: osteogenesis imperfecta.

Baseline characteristics of all 74 children included in the cross-sectional data analysis are listed in Table 3. In this cross-sectional analysis, the most recently performed lumbar BMD measurement of the longitudinal data analysis group was used together with the single lumbar BMD measurement in the remaining 22 children. Mean age in this remaining group of children with OI who underwent a single BMD measurement was 13.4 years (SD 4.0). Mean age in the total group of 74 children was 16.3 years (SD 4.3). The mean lumbar BMD at latest or single measurement of the whole cohort was 0.604 g/cm2 (SD 0.028). Lumbar BMD in this cohort of 74 children was statistically significantly higher for female sex, OI type I, walkers, and those of higher age, in both unadjusted and adjusted analysis. No influence of bisphosphonates was found on the last-measured lumbar BMD (Table 4).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of all 74 OI patients in the cross-sectional analysis

| Age at DEXA (mean, SD), years | 16.3 (4.3) |

| Male : Female, % | 47 : 52 |

| OI type I : III/IV, % | 58 : 42 |

| Bleck score; walker : non-walker, % | 56 : 44 |

| Bisphosphonate use; yes : no, % | 58 : 42 |

DEXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry;

OI: osteogenesis imperfecta.

Table 4.

Regression analysis concerning latest BMD measured in 74 patients with OI

| BMD (g/cm2) | Unadjusted (CI) | p-value | Adjusted(CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex a | –0.181 (–0.284 to –0.078) | 0.001 | –0.172 (–0.249 to –0.095) | < 0.001 |

| Bisphosphonate use | –0.062 (–0.174 to 0.050) | 0.3 | 0.065 (–0.017 to 0.147) | 0.1 |

| Walker/non-walker a | –0.183 (–0.287 to –0.079) | 0.001 | –0.120 (–0.217 to –0.024) | 0.02 |

| OI type I : III/IV a | –0.233 (–0.332 to –0.135) | < 0.001 | –0.165 (–0.261 to –0.070) | 0.001 |

| Age a | 0.023 (0.011 to 0.035) | < 0.001 | 0.024 (0.015 to 0.033) | < 0.001 |

a Significant association with latest or single BMD in unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

Reference categories: female sex, no bisphosphonate use, walker, OI of type I.

Regression coefficient is calculated for 1-year increment in age.

BMD: bone mineral density; OI: osteogenesis imperfecta.

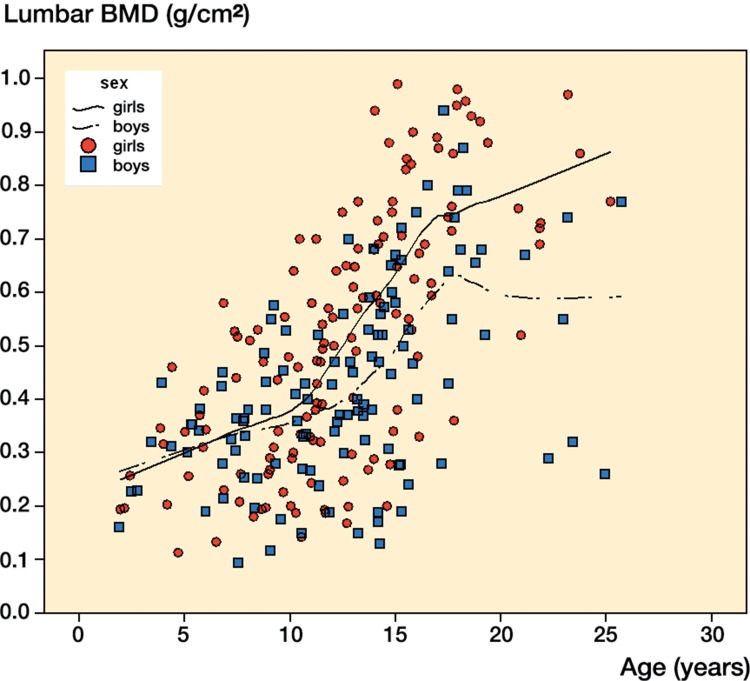

The Figure illustrates all lumbar BMD measurements in this cohort of children with OI during the 9-year follow-up. A line of fit was estimated for boys and girls separately.

All measurements together in a scatter plot of the total population of children with OI (n = 74), showing a trend in lumbar BMD development with age (137 measurements in girls and 117 in boys). BMD: bone mineral density; OI: osteogenesis imperfecta.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, the annual increase in BMD for each patient separately was estimated and used as a dependent variable in a linear regression to study the relation with various determinants of BMD. With this approach, all observations are used and the influence of outliers is minimized. However, it does not take into account within-subject dependency of measurements.

During 9 years of follow-up, lumbar BMD increased with a steeper annual coefficient in girls than in boys. One explanation may be that girls reach their peak bone mass during puberty earlier than boys do. Age at the last measurement was similar, 17.4 years in girls and 17.7 years in boys. It is possible that boys had not yet reached the maximum increase in lumbar BMD per year, during the 9-year follow-up. In healthy girls, volumetric peak bone mass is reached at around 16 years of age, and in healthy boys it is around 18 years of age (Boot et al. 2010). Longitudinal lumbar spine BMD measurements in 500 healthy Dutch children and adolescents (295 girls) aged 4–20 years also showed an increase with age. During puberty, in healthy children, the age-dependent increase was slightly higher than in children with OI. In healthy girls, the maximum increase in lumbar BMD was at 13 years of age; in healthy boys, this was at 15 years of age (Boot et al. 1997). In this retrospective study, no control group was used. To put our results into perspective, we used tables on healthy Dutch children. During the same follow-up period (9 years) and in the same age cohort, lumbar BMD increased by 0.46 g/cm2 in healthy Dutch children (Boot et al. 1997). Specified separately for boys and girls, increase in lumbar BMD during 9 years of follow-up in the same age group as in our study was 0.43 g/cm2 and 0.49 g/cm2, respectively. So in healthy Dutch children, BMD also increased more favorably in girls, during the same follow-up period in the same age cohort. It was not stated in that article whether the difference between sexes was significant (Boot et al. 1997).

Another explanation as to why lumbar BMD increased more in girls might be the positive relationship between body fat mass and lumbar bone mineral density (Arabi et al. 2004). Fat mass is a consistent positive predictor of BMD in healthy children, and is higher in girls during puberty (Arabi et al. 2004). This might explain a positive effect of estrogens in adipocytes on BMD in pubertal girls (Misra et al. 2011).

The latest-measured BMD in the cross-sectional adolescent OI population was also associated with ambulation level, as assessed using the Bleck score. These results should be interpreted with caution: this takes into account the ambulation level at the moment of cross-sectional analysis, and not ambulation in previous years. There is widespread support in the literature for positive effects of ambulation on BMD in healthy children and children with a chronic disease (Chad et al. 2000). This might be an explanation of why lumbar BMD in the cross-sectional analysis appeared to be more favorable in walkers than in non-walkers.

In the cross-sectional study group, in children with less severe OI (type I) the latest-measured BMD was higher than in children with severe OI (of types III and IV). In the literature, BMD specified according to OI type has not been investigated. The data available on DEXA measurements in children with OI of the lumbar spine concern children with mild OI; these children showed values that were 76% of the BMD values of healthy peers (Zionts et al. 1995).

In both analyses, we found no correlations between BMD increase and bisphosphonate use. This can most likely be ascribed to the study design, as the data on bisphosphonate use were inaccurate. A positive effect of both oral and intravenous bisphosphonates on BMD has been described in growing children (Glorieux et al. 1998, Gonzalez et al. 2001, Sakkers et al. 2004, Letocha et al. 2005, Phillipi et al. 2008, Ward et al. 2011, Mei et al. 2011). Our group have perfomed a double-blind randomized clinical trial concerning oral bisphosphonate treatment in children with OI, and in this controlled setting BMD increased favorably in the bisphosphonate group (Sakkers et al. 2004). In the total population investigated, 43 of 74 children used bisphosphonates. Treatment strategies in the bisphosphonate group were diverse: some were on cyclic intravenous pamidronate and others were on oral bisphosphonate, and the duration of treatment was also rather diverse. It should be noted that in the cross-sectional population, 22 children were examined years before the remaining 52 underwent a DEXA measurement. 1 child used bisphosphonates before the retrospective study started, and continued during follow-up. The retrospective character of this study makes it impossible to date the exact duration and timing of prescription. Generally speaking, if bisphosphonate was prescribed, the children were more severely affected by OI. Severely affected is defined as a lumbar BMD Z-score of below –2 SDs (adjusted for age), or suffering from many fractures. Comparison of the bisphosphonate group with the group who did not receive bisphosphonate was therefore a comparison between children with OI who were severely affected and those who were less affected. The children who are severely affected may have a more favorable development of OI during growth, due to bisphosphonate treatment. This might explain why differences with the mildly affected group, who did not receive bisphosphonates, might have been too small to be detected in this retrospective study.

The lumbar BMD in the total population increased during 9 years of follow-up, in both children treated with bisphosphonates and those treated without. The higher latest-measured lumbar BMD in girls cannot be explained by bisphosphonate use in this subgroup. A smaller proportion of girls (20 out of 39) were using bisphosphonates than boys (23 out of 35) at some time during this observational period. Another explanation for why no correlation was found between bisphosphonate use and latest-measured BMD was the relatively high age of this group at the latest measurement of BMD (16.3 years (SD 4.3)). In later years, younger children were treated with bisphosphonates at the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital. When treatment was started at a younger age, increase in BMD was more pronounced than in older children (unpublished data). Plotkin et al. (2000) and Dimeglio et al. (2004) described a spectacular increase in BMD in children with OI who were less than 3 years of age.

One strength of the present study was the large cohort of children with OI who were followed for almost 10 years. A weakness of our study was the retrospective character, which made it impossible to date all the parameters in growing children that might influence bone mineral development, such as pubertal stage, fracture treatment, and anthropometric measurements.

In conclusion, this study does not fully explain which determinants influence the density of developing bone most in children with OI. Over a 9-year follow-up period, there was an increase in BMD in OI—which was most apparent in girls. Ambulation and weight-bearing activities are important in this chronically ill population. The positive influence of ambulation level on latest-measured DEXA in the cross-sectional analysis was not sufficiently strong for us to draw conclusions concerning bone mineral development. In healthy growing children, ambulation is an important determinant of peak bone mass development (Cvijetic et al. 2010). Thus, we believe that in growing children, increases in BMD follow ambulation (Cvijetic et al. 2010). Based on these findings, doctors and healthcare workers should encourage physical activity in these chronically ill children to prevent the development of osteoporosis as much as possible as they become older (van Brussel et al. 2011).

Acknowledgments

No competing interests declared.

All the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, and/or acquisition of data, and/or analysis and interpretation of data. All participated in drafting the article or in revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all the authors approved the final version.

References

- Arabi A, Tamim H, Nabulsi M, Maalouf J, Khalife H, Choucair M, Vieth R, El-Hajj FG. Sex differences in the effect of body-composition variables on bone mass in healthy children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1428–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrom E, Soderhall S. Beneficial effect of long term intravenous bisphosphonate treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:356–64. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.5.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S, Sodini F, Saggese G. Osteoporosis in children and adolescents: etiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7:295–323. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot AM, de Ridder MA, Pols HA, Krenning EP, Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents: relation to puberty, calcium intake, and physical activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:57–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.1.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot AM, de Ridder MA, van d S. I, van S, I, Krenning EP, Keizer-Schrama SM. Peak bone mineral density, lean body mass and fractures. Bone. 2010;46:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo H, Samson-Fang L. Effects of bisphosphonates in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: an AACPDM systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:17–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepollaro C, Gonnelli S, Pondrelli C, Montagnani A, Martini S, Bruni D, Gennari C. Osteogenesis imperfecta: bone turnover, bone density, and ultrasound parameters. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65:129–32. doi: 10.1007/s002239900670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chad KE, McKay HA, Zello GA, Bailey DA, Faulkner RA, Snyder RE. Body composition in nutritionally adequate ambulatory and non-ambulatory children with cerebral palsy and a healthy reference group. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:334–9. doi: 10.1017/s001216220000058x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvijetic S, Colic B. I, Satalic Z. Influence of heredity and environment on peak bone density: a parent-offspring study 1. J Clin Densitom. 2010;13:301–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeglio LA, Ford L, McClintock C, Peacock M. Intravenous pamidronate treatment of children under 36 months of age with osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone. 2004;35:1038–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbert RH, van der GY, van Empelen R, Beemer FA, Helders PJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta in childhood: impairment and disability. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E3. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux FH, Bishop NJ, Plotkin H, Chabot G, Lanoue G, Travers R. Cyclic administration of pamidronate in children with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:947–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez E, Pavia C, Ros J, Villaronga M, Valls C, Escola J. Efficacy of low dose schedule pamidronate infusion in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14:529–33. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letocha AD, Cintas HL, Troendle JF, Reynolds JC, Cann CE, Chernoff EJ, Hill SC, Gerber LH, Marini JC. Controlled Trial of Pamidronate in Children With Types III and IV Osteogenesis Imperfecta Confirms Vertebral Gains but Not Short-Term Functional Improvement. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:977–86. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AM, Molgaard C, Muller J, Skovby F. Bone mineral content and collagen defects in osteogenesis imperfecta. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1083–8. doi: 10.1080/08035259950168135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei L, Xia W, Yu W. Benefit of infusions with ibandronate treatment in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;19:3049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra M, Katzman D, Miller K, Mendes N, Snelgrove D, Russell M, Goldstein MA, Ebrahimi S, Clauss L, Weigel T, Mickley D, Schoenfeld DA, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Physiologic estrogen replacement increases bone density in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2430–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipi CA, Remmington T, Steiner RD. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005088.pub2. CD005088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin H, Rauch F, Bishop NJ, Montpetit K, Ruck-Gibis J, Travers R, Glorieux FH. Pamidronate treatment of severe osteogenesis imperfecta in children under 3 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1846–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.5.6584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch F, Travers R, Plotkin H, Glorieux FH. The effects of intravenous pamidronate on the bone tissue of children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1293–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI15952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinus WR, McAlister WH, Schranck F, Chines A, Whyte MP. Differing lumbar vertebral mineralization rates in ambulatory pediatric patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;62:17–20. doi: 10.1007/s002239900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkers R, Kok D, Engelbert R, van Dongen A, Jansen M, Pruijs H, Verbout A, Schweitzer D, Uiterwaal C. Skeletal effects and functional outcome with olpadronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta: a 2-year randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2004;363:1427–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonau E. The peak bone mass concept: is it still relevant? Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:825–31. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1465-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16:101–16. doi: 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brussel M, van der NJ, Hulzebos E, Helders PJ, Takken T. The Utrecht approach to exercise in chronic childhood conditions: the decade in review. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23:2–14. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e318208cb22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis I, Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Osteoporosis in childhood: bone density of children in health and disease. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14:817–32. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.7.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk FS, Cobben JM, Maugeri A, Nikkels PG, van Rijn RR, Pals G. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Rauch F, Whyte MP, D’Astous J, Gates PE, Grogan D, Lester EL, McCall RE, Pressly TA, Sanders JO, Smith PA, Steiner RD, Sullivan E, Tyerman G, Smith-Wright DL, Verbruggen N, Heyden N, Lombardi A, Glorieux FH. Alendronate for the treatment of pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:355–64. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggemans RM, Schaafsma G, Kromhout D, Towards an adequate intake of vitamin D. An advisory report of the Health Council of the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:1455–7. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zionts LE, Nash JP, Rude R, Ross T, Stott NS. Bone mineral density in children with mild osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77:143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]