In 2009, a 62-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis and a total hip arthroplasty (THA) on the right (uncemented Ti-6AL-7Nb stem combined with a Ti threaded cup, polyethylene inlay, and a 28-mm ceramic head; Zweymuller Alloclassic; Zimmer Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN) implanted in 2006 presented with a left femoral neck fracture. A THA with a double-mobility acetabular system (Avantage Double-Mobility Acetabular System; Biomet, Warsaw, IN) was implanted. An uncemented titanium-niobium (Ti-6Al-7Nb) stem was used (Zweymuller Alloclassic; Zimmer) with a 12/14 mm trunnion combined with an XXL (+10.5 mm) 28-mm cobalt-chromium head with a 12/14 mm tapered bore (Biomet). The femoral head was introduced into the highly cross-linked, vitamin E-stabilized polyethylene bearing using a bearing press. An uncemented Ti HA-coated 52-mm acetabular shell was press-fitted in the socket and the large polyethylene femoral head was reduced into the metal articular surface. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, with normal wound healing.

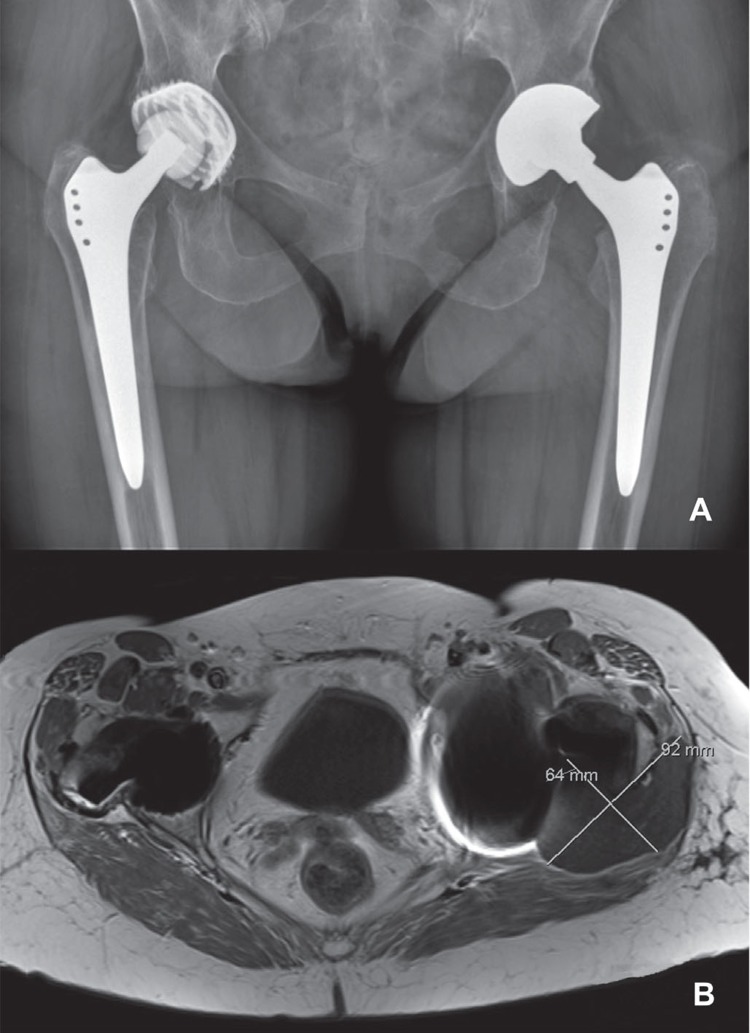

2 years after implantation, the patient was referred to our center by her rheumatologist, since a soft tissue mass adjacent to the left THA had been diagnosed by ultrasound. A standard AP pelvic radiograph revealed adequate positioning of both hip implants without any signs of wear or osteolysis. Subsequent MARS-MRI scanning confirmed the presence of a 6 × 9 cm soft tissue mass at the posterolateral aspect of the left greater trochanter (Figure 1). There were no signs of any soft tissue reaction around the contralateral THA.

Figure 1.

Standard AP radiograph (panel A) and MARS-MRI scan (panel B) 2 years after implantation of the left THA with a double-mobility acetabular component. Note the adequate implant positioning and fixation (A) and a 6 × 9 cm soft tissue mass (B) at the posterolateral side of the left femoral component. On the right, there were no signs of periprosthetic soft tissue reaction.

CRP was 68 mg/L and ESR was 53 mm/h; both were elevated, but this was possibly related to her rheumatoid arthritis. An inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) was used for evaluation of metal ion levels. Serum levels of chromium were below the detection level of 0.5µg/L, whereas cobalt serum levels were 5.7 µg/L. An aspirate of the hip joint was negative for bacterial or fungal growth.

The patient was diagnosed as having a severe and early “adverse local tissue reaction” (ALTR) after a metal-on-polyethylene bearing THA with the taper as the potential source of the metal ion release. 2.5 years after implantation, a debulking procedure of the pseudotumor in combination with a 1-stage revision of the femoral component was performed.

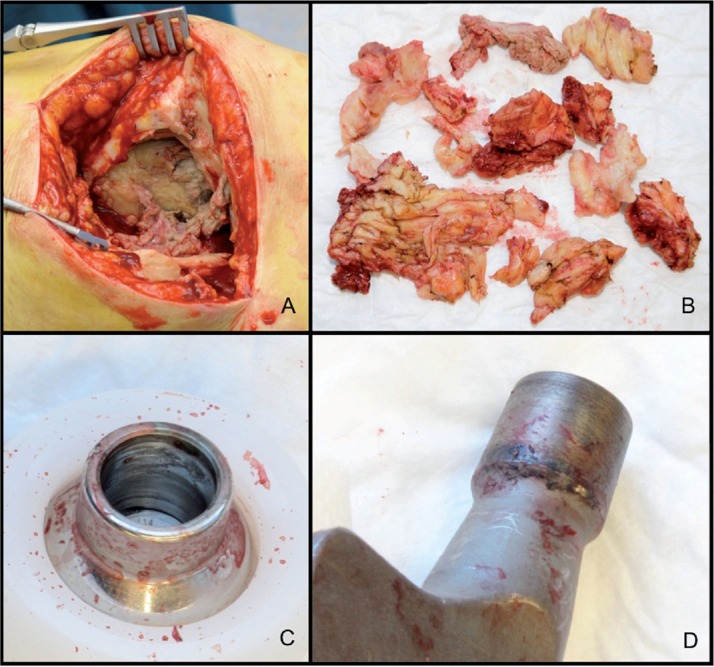

Perioperatively, extensive tissue necrosis and partial destruction of the abductor mechanism were found in the absence of any macroscopic signs of infection. The acetabular component was well fixed. Both the femoral trunnion and bore of the head showed signs of black debris (Figure 2). The femoral component was revised to a cemented polished straight stem (Exeter; Stryker, Allendale, NJ) with a ceramic 28-mm head (also Stryker) and a new double-mobility liner (Avantage Double-Mobility Acetabular System; Biomet). At the revision operation, 6 tissue samples were taken for bacterial culture according to our protocol. All 6 samples were negative for bacterial growth.

Figure 2.

A. Extensive necrosis at the greater trochanter area and destruction of the abductor mechanism. B. Debulking of large amounts of necrotic and fibrotic tissue from the periprosthetic region. C and D. Macroscopic signs of corrosion products at the bore of the Co-Cr head (panel C) and at the trunnion of the femoral component (panel D).

The revision procedure was complicated by a deep infection that was unresponsive to lavage and prolonged antibiotic treatment. 2 months after revision, all components had to be removed, resulting in a (temporary) Girdlestone situation.

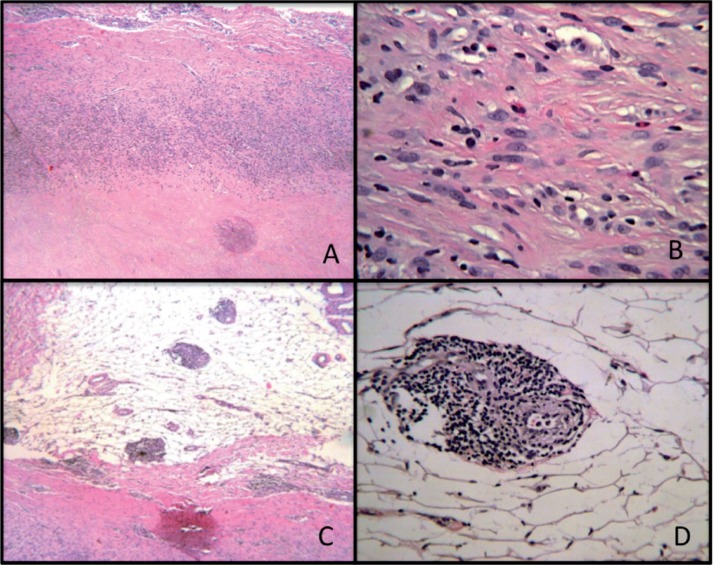

The components were sent for retrieval analysis. Multiple samples of the periprosthetic tissues were processed in paraffin for routine histology. The histopathology of tissue samples revealed extensively necrotic material with only a focal cellular area of inflammatory cells containing macrophages, plasma cells, occasional foci of eosinophils, and several small perivascular lymphocytic aggregates (Figure 3). No polarizable materials or metallic debris were present in several tissue samples. The ALVAL score (Campbell et al. 2010) was 3 + 3 + 2 (= 8/10, moderate). Overall, the histological profile was consistent with an adverse immunological reaction in the absence of visible wear debris.

Figure 3.

A. Histological view of the soft tissue mass at the interface between the necrotic material (on the joint side) and inflammatory cells. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE), 40×. B. Enlargement of A with inflammatory cells consisting mainly of macrophages and lymphocytes along with plasma cells and eosinophils. HE, 200×. Several lymphocytic aggregates were observed at low magnification (panel C; HE, 40×) and at high magnification (panel D; HE, 200×).

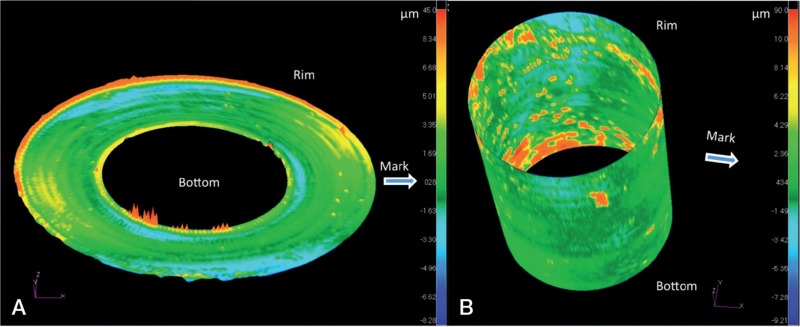

The profile of the ball taper was measured using a coordinate measuring machine (Legex 322; Mitotoyo, Aurora, IL). The dimensions of a perfect taper based on 6726 CMM points with a point spacing of 0.3 mm were determined using a least-squares method. The taper had an angle of 5 degrees, 47 min, and 34 s. A contour map was generated using the deviations of the CMM points from the fitting taper (Figure 4). The CMM results indicated uneven areas of contact, but the amount of material that had been removed through wear or corrosion could not be determined without knowing the initial form of the parts. However, in combination with the microanalysis described below, it appears that the small degree of texture and color changes was consistent with mild corrosion

Figure 4.

A. 2-dimensional graphical representation of the same profile. The outer diameter of the CMM map is the portion of the taper closest to the stem (labeled Rim) and the inner diameter of the CMM image corresponds to the inner surface (labeled Bottom). Areas with differences in color intensity may be related to wear or corrosion from the original dimensions. B. 3-dimensional map with the portion closest to the stem labeled Rim and the deepest portion of the taper closest to the bearing surface labeled Bottom. Note the uneven distribution of color, corresponding to differences in contact with the trunnion.

The area of the stem trunnion that appeared discolored was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive analysis of X-rays (EDAX) to identify the elements present. Organic material containing chromium and/or molybdenum consistent with corrosion products was identified within the machined grooves and in the deposited dark material outside the trunnion (Figure 5). Similar analysis performed on deparaffinized soft tissue sections failed to demonstrate any wear or corrosion products.

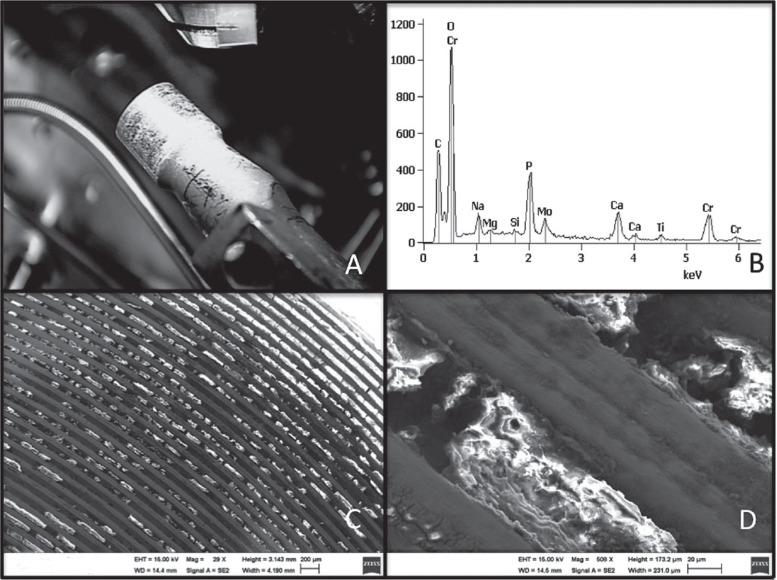

Figure 5.

Material present on the trunnion of the femoral component (panel A) was investigated by EDAX, revealing chromium (Cr), molybdenum (Mo), and oxygen (O) peaks consistent with corrosion products (panel B). The organic material within the grooves containing chromium oxides is shown at approx. 30× (panel C) and 500× magnification (panel D).

Discussion

We describe a patient with a rapidly forming, large and destructive pseudotumor as a form of ALTR after a THA with a double-mobility metal-on-polyethylene bearing. The exact pathogenesis of periprosthetic adverse reactions is still unknown, but a frequently suggested hypothesis is the contribution of wear particles and ions from corrosion, particularly from articulating surfaces of MoM hip implants (Pandit et al. 2008, Campbell et al. 2010, Kwon et al. 2010, Langton et al. 2010). However, any MoM connection in a total hip arthroplasty could theoretically be a source of metal debris and ions. These MoM connections are diverse, with increasing modular options. The exact origin of the metal debris is often obscure, with the combined use of modular MoM junctions and MoM articulating bearings in the same implant (Langton et al. 2011, Vendittoli et al. 2011). Numerous authors have reported higher metal ion levels and incidences of ALTR after large-diameter MoM total hip arthroplasty (THA) than after resurfacing hip arthroplasty (RHA) using identical articulation characteristics (Garbuz et al. 2010, Vendittoli et al. 2011). The latter lacks any modular MoM junctions, which may explain the difference encountered. To date, there is very little literature available to explain the extent to which the taper contributes to the release of metal particles, corrosion products including ions, and ALTR (Collier et al. 1992, Langton et al. 2011, Cooper et al. 2012, Gill et al. 2012, Vundelinckx et al. 2013).

Our case is interesting, as the ALTR could only have been triggered by metal ion release from the head-neck taper junction since no other MoM articulating surface was used. ALTR can also be associated with polyethylene wear (Leigh et al. 2008). However, in this case polyethylene wear was not a likely cause of the massive pseudotumor since the hip arthroplasty was only 2 years in situ, which is a short time for abundant polyethylene wear to occur, and this is consistent with the lack of polyethylene debris in the tissues.

Furthermore, the SEM and EDAX analysis showed corrosion products on the trunnion. Corrosion and wear at this modular head-neck junction can occur when a passive protective oxide film on the metallic surfaces is constantly disrupted by fretting and micromotion (Gilbert et al. 1993, Jacobs et al. 1998). The extent of the corrosion process is affected by a number of factors, including the amount and quality of metallic junctions and forces that are projected on the junctions (Brown et al. 1995, Jacobs et al. 1998, Goldberg et al. 2002, Goldberg and Gilbert 2003).

In our case, several factors may have contributed to the release of metal corrosion products from the head-neck junction together with the rapid formation of a massive pseudotumor. First, the quality of the tapered head-neck junction may have been impaired by a subtle mismatch between components from different manufacturers. Both the head and neck had a 12/14 taper, which indicates a gradual decrease in diameter from 14 mm to 12 mm. In contrast to what is commonly believed, a 12/14 taper is not standard and can reveal subtle inter- and intra-manufacturer differences between components. In fact, it is the angle by which the taper goes from 14 to 12 mm that truly determines its profile. This angle is expressed in degrees, minutes, and seconds where 1 degree is made up of 60 minutes and 1 minute has 60 seconds. In our case, according to manufacturer-derived data, the implanted stem trunnion had a 12/14 taper with a 5-degree, 38-min, and 0-s taper, and the head had a 5-degree, 42-min, and 30-s taper. The amount of manufacturing tolerance of these parts is not known but the ball taper was demonstrated by CMM to be 5 degrees, 47 min, and 34 s, which may reflect the allowable tolerance, the effect of wear or corrosion, or a combination of the two. Even a subtle angular mismatch between the trunnion and taper may have led to an incongruence of the head-neck junction, leading to increased wear and corrosion. The release of metal debris from a modular junction due to a mismatch of components from different manufacturers has recently been addressed by Chana et al. (2012). However, reports on release of metal debris from the head-neck junction are also available with the use of components from the same manufacturer (Cooper et al. 2012). This may be related to the fact that for a given taper from one manufacturer, the angle may also differ by a few minutes of a degree within the accepted range of tolerance. This tolerance is generally higher for ceramic heads than for metallic ones as used in this case (Hallab et al. 2004).

Secondly, the corrosion may partly be explained by increased mechanical stresses on the head-neck junction. In a sense, the double-mobility acetabular system mimics the configuration of a large-diameter femoral head. An increase in head diameter may cause the frictional force between the articulating surfaces to produce a greater frictional torque at the head-neck interface and may facilitate mechanically assisted fretting corrosion. Similarly, when the articulating surface is medialized with a large-diameter head, the frictional torque may be increased on the taper junction due to the greater length of arm. Forces on the taper may be even further increased when longer necks are used. Brown et al. (1995) found a correlation between corrosion and the length of neck extensions. They concluded that longer head-neck extensions may be more susceptible to fretting and crevice corrosion because of instability at the interface. This was also confirmed in a study by Lavigne et al. (2011), where higher cobalt ion levels were seen in patients with longer sleeve lengths than in those with shorter lengths at 12 months of follow-up. In our case, the double-mobility system may have led to greater stresses on the taper junction according to the same principle that applies to large-diameter head THAs. A +10.5-mm (XXL) extended head increased the lever arm and applied even greater forces to the taper junction. Although contact stress may account for the contour irregularities observed (Figure 4), corrosion may have occurred without the presence of contact stress, which makes it difficult to definitively attribute the contour irregularities to contact stress alone.

Apart from the relatively increased lever arm and the possible taper mismatch, important patient factors may also have had a role in the formation of this destructive pseudotumor. Unknown patient susceptibility factors (Hart et al. 2012, Matthies et al. 2012) or metal hypersensitivity (Willert et al. 2005, Campbell et al. 2010,) could explain pseudotumor formation. In a study by Matthies et al. (2012), pseudotumors were common in patients with well-positioned prostheses and were not necessarily associated with high wear or high metal ion levels. Moreover, Hart et al. (2012) found that a considerable proportion of unexplained hip pain could not be related to either excessive wear or elevated metal ion levels. They proposed that a patient susceptibility factor caused at least a proportion of the hip arthroplasty failures. Our patient may have been more vulnerable to developing ALTR due to her history of rheumatoid arthritis. In addition, corrosion at the trunnion from her earlier contralateral THA may have alerted her immune system to the metal debris released at the pseudotumor side. The rapid formation of the mass, the impressive surgical and histological findings in the surprising absence of substantial wear, and only moderate levels of ions may be explained by heightened sensitivity. The histological evaluation was based on only a small area of viable tissue but the features were comparable to several other cases with low wear-related pseudotumors attributed to metal allergy (Campbell et al. 2010). Although rheumatoid arthritis and metal hypersensitivity share lymphocytic predominance as a characteristic immunohistological feature, no studies have supported the association between rheumatoid arthritis and ALTR. However, given the profound immune response in rheumatoid arthritis, it is conceivable that rheumatoid arthritis may enhance the development of ALTR.

Finally, an Alloclassic uncemented titanium-niobium (Ti6A/7Nb) stem was combined with a cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr) articulating prosthetic head. Differences in electrical potential may cause galvanic corrosion when 2 different metals are in contact in an electrolyte solution (Jacobs et al. 1998). There is evidence that mixed-alloy combinations are associated with a higher corrosion incidence than similar-alloy combinations (Collier et al. 1992, Goldberg et al. 2002, Goldberg and Gilbert 2003). However, the role of galvanic corrosion in the latter is still debated, whereas the electrochemical gradient between Co-Cr and Ti alloys is said to be small (Lucas et al. 1981). In our patient, the fact that there were relatively low chromium ion levels (0.5 µg/L) relative to cobalt levels in serum (5.7 µg/L) makes it likely that there was corrosion.

In conclusion, we believe that several factors have had a role in the development of a severe ALTR in our patient. It is most likely that we were confronted with a profound patient-related immunological response to a moderate amount of metal debris and corrosion products from the mismatched head-neck junction. One should be aware that, with or without a MoM articular bearing, the head-neck junction may also be a source of metal debris and corrosion products and can then trigger the development of ALTR. In spite of the fact that there are also subtle taper mismatches between components from the same company, mixing components from different companies should be avoided if possible.

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was a collaboration between all the authors, who contributed to and approved the manuscript. ZL performed analysis of retrieved material.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Brown SA, Flemming CA, Kawalec JS, Placko HE, Vassaux C, Merritt K, Payer JH, Kraay MJ. Fretting corrosion accelerates crevice corrosion of modular hip tapers . J Appl Biomater. 1995;6(1):19–26. doi: 10.1002/jab.770060104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P, Ebramzadeh E, Nelson S, Takamura K, De Smet K, Amstutz HC. Histological features of pseudotumor-like tissues from metal-on-metal hips . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(9):2321. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1372-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chana R, Esposito C, Campbell PA, Walter WK, Walter WL. Mixing and matching causing taper wear: corrosion associated with pseudotumour formation . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94:2, 281–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B2.27247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JP, Surprenant VA, Jensen RE, Mayor MB, Surprenant HP. Corrosion between the components of modular femoral hip prostheses . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74:4, 511–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B4.1624507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, Tetreault M, Paprosky WG, Sporer SM, Jacobs JJ. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(18):1655–61. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbuz DS, Tanzer M, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP. The John Charnley Award: Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing versus large-diameter head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial . Clin Orthop. 2010;2(468):318–25. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1029-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JL, Buckley CA, Jacobs JJ. In vivo corrosion of modular hip prosthesis components in mixed and similar metal combinations. The effect of crevice, stress, motion, and alloy coupling . J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(12):1533–44. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill IP, Webb J, Sloan K, Beaver RJ. Corrosion at the neck-stem junction as a cause of metal ion release and pseudotumour formation . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94(7):895–900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.29122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JR, Gilbert JL. In vitro corrosion testing of modular hip tapers . J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2003;64(2):78–93. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JR, Gilbert JL, Jacobs JJ, Bauer TW, Paprosky W, Leurgans S. A multicenter retrieval study of the taper interfaces of modular hip prostheses . Clin Orthop. 2002;(401):149–61. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallab NJ, Messina C, Skipor A, Jacobs JJ. Differences in the fretting corrosion of metal-metal and ceramic-metal modular junctions of total hip replacements . J Orthop Res. 2004;22(2):250–9. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AJ, Matthies A, Henckel J, Ilo K, Skinner J, Noble PC. Understanding why metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties fail: a comparison between patients with well-functioning and revised birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasties. AAOS exhibit selection . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(4):e22. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JJ, Gilbert JL, Urban RM. Corrosion of metal orthopaedic implants . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998;80:2, 268–82. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199802000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YM, Glyn-Jones S, Simpson DJ, Kamali A, McLardy-Smith P, Gill HS, Murray DW. Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on-metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumours . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(3):356–61. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, Hallab NJ, Natu S, Nargol AV. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: A consequence of excess wear . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(1):38–46. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, Gandhi JN, Sidaginamale R, Mereddy P, Lord J, Nargol AV. Accelerating failure rate of the ASR total hip replacement . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(8):1011–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.26040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne M, Belzile EL, Roy A, Morin F, Amzica T, Vendittoli PA. Comparison of whole-blood metal ion levels in four types of metal-on-metal large-diameter femoral head total hip arthroplasty: the potential influence of the adapter sleeve . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2011;93:128–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh W, O’Grady P, Lawson EM, Hung NA, Theis JC, Matheson J. Pelvic pseudotumor: an unusual presentation of an extra-articular granuloma in a well-fixed total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6):934–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas LC, Buchanan RA, Lemons JE. Investigations on the galvanic corrosion of multialloy total hip prostheses . J Biomed Mater Res. 1981;15(5):731–47. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820150509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies AK, Skinner JA, Osmani H, Henckel J, Hart AJ. Pseudotumors are common in well-positioned low-wearing metal-on-metal hips . Clin Orthop. 2012;7(470):1895–906. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90:7, 847–51. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendittoli PA, Amzica T, Roy AG, Lusignan D, Girard J, Lavigne M. Metal Ion release with large-diameter metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(2):282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vundelinckx BJ, Verhelst LA, De Schepper J. Taper corrosion in modular hip prostheses: Analysis of serum metal ions in 19 patients . J Arthroplasty. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.01.018. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Koster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87:1, 28–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.A.02039pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]