Abstract

Primary cilia are multisensory organelles recently found to be absent in some tumor cells, but the mechanisms of deciliation and the role of cilia in tumor biology remain unclear. Cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells lining the biliary tree, normally express primary cilia and their interaction with bile components regulates multiple processes, including proliferation and transport. Utilizing cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) as a model, we found primary cilia are reduced in CCA by a mechanism involving histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6). The experimental deciliation of normal cholangiocyte cells increased the proliferation rate and induced anchorage-independent growth. Furthermore, deciliation induced the activation of MAPK and Hedgehog signaling, two important pathways involved in CCA development. We found HDAC6 is overexpressed in CCA and overexpression of HDAC6 in normal cholangiocytes induced deciliation, and increased both proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. To evaluate the effect of cilia restoration on tumor cells, we targeted HDAC6 by shRNA or by the pharmacologic inhibitor, tubastatin-A. Both approaches restored the expression of primary cilia in CCA cell lines and decreased cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. The effects of tubastatin-A were abolished when CCA cells were rendered unable to regenerate cilia by stable transfection of IFT88-shRNA. Finally, inhibition of HDAC6 by tubastatin-A also induced a significant decrease in tumor growth in a CCA animal model. Our data support a key role for primary cilia in malignant transformation, provide a plausible mechanism for their involvement, and suggest that restoration of primary cilia in tumor cells by HDAC6 targeting may be a potential therapeutic approach for CCA.

INTRODUCTION

Primary cilia are microtubule based organelles that function as multisensors of the extracellular environment (1). Interest in primary cilia has increased markedly over the last 15 years, since it was observed that mutations in genes required for the assembly and/or the sensory properties of cilia result in diverse human disorders like visceral epithelial hyperplasia, polycystic kidneys, pancreas and liver among other abnormalities (2). Recent observations also suggest a relationship between ciliary structure/function and tumorigenesis. For example, Aurora A kinase mediates ciliary disassembly and is overexpressed in many epithelial cancers (3). Nek8, a kinase expressed in primary cilia that regulates ciliogenesis, is increased in breast cancer (2, 4); and the loss of the VHL tumor suppressor gene inhibits ciliogenesis and is associated with renal cancers (5, 6). Also mutations in mice of Tg737, the mammalian homolog of Chlamydomonas IFT88, a key component for ciliary formation (7) accelerate the rate at which chemical carcinogens induce liver neoplasms (8). Finally, very recent findings showed reduced expression of cilia in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (2), renal cancer (6), astrocytoma/glioblastoma (9), and breast cancer (10). While these data suggest that ciliary dysfunction may be associated with cancer development, the mechanisms leading to ciliary reduction in tumor cells as well as the consequences of such a lost remain poorly understood, and are the subject of the present manuscript.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignancy thought to be derived from cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells lining the biliary tree. CCA is a highly aggressive tumor whose incidence has been increasing worldwide over the past two decades, now accounting for 10–15% of all hepatobiliary malignancies. Advanced CCA has a devastating prognosis, with a median survival of less than 24 months (11, 12).

Cholangiocytes normally express primary cilia extending from their apical plasma membrane into the ductal lumen. In cholangiocytes, the primary cilium functions as a multi-sensor of the extracellular milieu detecting a wide variety of chemical and physical stimuli. Indeed, we reported that cholangiocyte primary cilia are mechano-, chemo- and osmosensory organelles (13–16).

In the present manuscript, we describe that ciliary expression is decreased in CCA by a mechanism involving overexpression of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6). We found that targeting HDAC6 in CCA cells decreases the tumorigenic phenotype of the cells in a ciliary re-expression dependent manner in vitro and in an animal model of CCA. The data not only shed light on the mechanisms by which ciliary disassembly facilitate malignant transformation but also identify a potential molecular target for CCA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture

The normal human cholangiocytes (H69 and NHC) and the normal rat (NRC) cell lines were manteined as previously described (13, 17, 18). The human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines (HuCCT-1(19) and KMCH(20)) and the rat cholangiocarcinoma cell line (BDEneu(21, 22)) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100ug/Ml streptomycin, and 100 ug/L insulin.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and synthesized into cDNA using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR for HDAC6 was performed using 1 μl of cDNA and the Light Cycler Fast Start DNA MasterPlus SYBR Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics) as previously described (23). The primers used were HDAC6 sense (5′-AGTCTTATGGATGGCTATTGCATG-3′), HDAC6 antisense (5′-TGGACCAGTTAGAGGCCTTCAGG-3′), PTCH1 sense (5′-CGCTGTCTTCCTTCTGAACC-3′), and PTCH1 antisense (5′-ATCAGCACTCCCAGCAGAGT-3′). IFT88 expression were analyzed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Assay ID Hs00197926_m1) from Applied Biosystems following the manufacturer directions. The samples were normalized to 18 S rRNA.

Immunfluorescences

Liver sections were incubated with antibodies against acetylatedα-tubulin (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), ift88 (1:100, Proteintech), CK19 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology or Abcam), γ-tubulin (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich), PCNA (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and/or HDAC6 (1:100, Abcam) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation for 1 h with fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:100). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Prolong Gold w/DAPI, Invitrogen). For HDAC6-flag expression analysis, cells were transfected with the Addgene plasmid 13823 (Dr. Eric Verdin(24)) using Fugene reagent (Roche). After 3 days of incubation in media without serum, cells were fixed and stained for ciliary markers acetylated α-tubulin and/or ift88 and ciliated cells were analyzed under the confocal microscopy.

Scanning electron microscopy

Cells were processed as previously described(25).

Chemical and molecular deciliation

Chemical deciliation was carried out by treatment with 4mM chloral hydrate as previously described (26). Molecular deciliation was obtained by stably transfection with ift88, Kif3a, or Cep164 shRNA plasmids (Supp Table 1).

Proliferation assays

Proliferation assays were carried out using the CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS) (Promega) and/or counting cells using the Cellometer Auto4 (Nexcelom Bioscience) cell counter.

Anchorage-independent growth

Anchorage independent growth was assessed by growing cells in soft agar. 25,000 cells supended in 0.4% agar in culture media were layered over a 1% agar layer in a six-well plate. Media was added twice a week and pictures were taken after 14–21 days of incubation. The number and size of colonies were analyzed using the Gel-Pro software.

Invasion assays

Invasion assays were performed using the CytoSelect 24-well cell invasion Assay kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc.) following the manufacturer directions.

Western blots

Protein fractions were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following antibodies: HDAC6 (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Erk (1:2000, Abcam), p-Erk (1:1000, BD Biosciences), Gli1 (1:500, Abcam), ift88 (1:1000, Proteintech), Kif3a (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Cep164 (1:500, Genetex), IL-6 (1:500, Santa Cruz), bcl-2 (1:1000, Santa Cruz), actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich or Abcam), acetylated-α-tubulin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich); washed and incubated 1 h at room temperature with HRP conjugated (1:5000, Invitrogen) or IRdye 680 or 800 (1:15000, Odyssey) corresponding secondary antibody. For protein detection, ECL system or Odyssey Liquor Scanner was employed, and the Gel-Pro Analyzer 6.0 software was used for densitometric analysis.

In vivo experiments

All animal experimentation was performed in accordance with and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In vivo cell transplantation was carried out in adult fisher 344 male rats (Harlan) with initial mean body weights ranging between 200 and 250 g, as previously described(21, 27, 28). Five days after tumor implantation, animals were treated daily with tubastatinA (10 mg/100g body weight i.p.) or vehicle for 7 days. After treatment, animals were euthanized and the livers were removed for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed by One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posthoc test to compare more than two groups and by the Student t test to compare two groups. Results were considered statistically different at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Primary cilia are reduced in CCA in vivo and in vitro

To assess the expression of primary cilia in CCA, we stained liver samples from 21 CCA patients and 6 normal controls with the ciliary markers, acetylated α-tubulin and/or IFT88, and the cholangiocyte marker, CK19. We found that while 100% of bile ducts from normal controls show primary cilia, only 20% are ciliated in CCA samples (Figure 1A–E). We found a similar situation when we stained a commercially available CCA tissue array (AccuMax Array A205(II), Supp. Figure 1). To further explore the differential expression of primary cilia, we assessed their expression on two normal human cholangiocyte cell lines (H69, NHC), and the CCA cell lines Hucct-1 and KMCH. Ciliary expression was induced by serum starvation (15) and assessed by staining with acetylated α-tubulin, IFT88, and the centrosome marker,γ-tubulin; our results showed that only 3% (Hucct-1) and 1.8% (KMCH) of the CCA cell lines express cilia, while in the normal cell lines cilia were found in 67% (H69) and 61% (NHC) of the cells, respectively (Figure 1F–H). Finally, to confirm ciliary loss in CCA cells we performed scanning electron microscopy of the apical surface of normal and CCA cells (Figure 1I–L).

Figure 1. Primary cilia are reduced in Cholangiocarcinoma.

Confocal immnunofluorescence for two ciliary markers, acetylated-α-tubulin in red, and IFT88 in purple. Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI. Cilia are easily appreciated on the bile duct lumen of control normal human tissue and on normal cholangiocyte cell lines (A, C, F). Even though the red and purple signals were saturated, reduced amount of ciliary structures were found on cholangiocarcinoma samples (B, D) or in the cell lines HuCCT-1 (G) and KMCH as shown in the accompanying quantifications (E, H). In vivo, the cholangiocyte marker CK19, and in vitro, the centrosome marker γ-tubulin, were stained in green. (*p<0.0001, n=21; #p<0.001, n=110). I–L, Scanning electron microscopy of the apical surface of normal rat cholangiocytes (NRCs) and the rat CCA cells BDEneu.

Deciliation of normal cholangiocytes induces proliferation, anchorage independent growth, and invasion

In order to explore the potential relationship between ciliary loss and cholangiocyte phenotype, we assessed the effect of deciliation on normal human (ie, H69) and rat (NRC) cholangiocyte cell lines. First, we induced chemical deciliation by ClHy treatment(15); deciliation by this manipulation increased normal cholangiocyte proliferation by 2-fold (Figure 2A). We complemented this approach of chemical deciliation by molecular deciliation using specific shRNAs against IFT88, Kif3a or Cep164 (Supp. Figure 2); this approach caused an increase in cell proliferation by 1.89-fold, 1.77-fold, and 1.63-fold, respectively (Figure 2B). The increased proliferation was confirmed by nucleotide incorporation assays (Supp. Figure 3). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis showed an increase in G2/M and a decrease in G1/G0 phases in IFT88-shRNA deciliated cells compared to normal NT-shRNA controls (Supp. Figure 4), further supporting increased proliferation. To further characterize the effect of ciliary loss, we assessed anchorage-independent growth and invasion, and found that deciliation by IFT88 shRNAs induced both parameters by 6- and 3-fold, respectively; and by 3-fold and 2-fold, respectively when deciliation was induced by Kif3a shRNAs (Figure 2C, D). Finally, we analyzed the status of the Hh signaling pathway by RT-PCR of patched mRNA and western blots for Gli1, IL6 and Bcl2; and the MAPK signaling pathway by western blot, and found that deciliation induced activation of both hedgehog and MAPK signaling pathways (Figure 2E, F, and Supp. Figure 2). Taken together, these data suggest that experimentally induced deciliation stimulates a phenotypic transformation of normal cholangiocytes in culture to a malignant phenotype.

Figure 2. Cholangiocyte deciliation induces a malignant-like phenotype.

A, SEM images from control NRCs showed normal cilia (left panel) but when treated with ClHy for 24 hrs, cilia were absent (right panel). Proliferation rates were measured by MTS assay. NRCs and H69 cells were followed during 3 days after deciliation. B, SEM (top panels) and IF (botton panels) images from scrambled non-target (NT) control and IFT88 shRNA H69 tranfected cells cultured 3 days in minimal medium. Acetylated-α-tubulin, a ciliary marker, is stained in red. Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI. Proliferation rates for IFT88-, Kif3a-, Cep164-, or non-target- (NT) shRNAs stable transfected cells were measured by MTS assay. C, non-target (NT) control and IFT88 or Kif3a shRNAs tranfected cells were cultured 21 days in soft agar. Colonies quantification for IFT88, and Kif3a shRNAs cells showed a 6-fold and 3-fold increase compared to NT shRNAs cells, respectivelly. D, Invasion assays where cells were cultured on polycarbonate membrane inserts coated with uniform layer of basement membrane in 24-well plates (CytoSelect 24-well cell invasion Assay, Cell Biolabs). E, NRCs and H69 cells were deciliated with ClHy and IFT88 shRNAs, respectively, and Patched mRNA levels, a marker of the Hedgehog pathway activation, were quantified by real time PCR. F, Normal cells stably transfected with Kif3a, Cep164, or IFT88 shRNAs show elevated p-ERK/t-ERK ratio, Gli1, and IL6 compared to non-target controls.

HDAC6 is overexpressed in CCA and decreases ciliary expression

To explore the potential mechanisms involved in the CCA decreased ciliary expression, we analyzed HDAC6, a tubulin deacetylase reported to induce ciliary resorption in the immortalized retinal pigment epithelial cell line hTERT-RPE1(3); moreover, evidence in the literature suggests an important role for HDAC6 overexpression in tumorigenesis(29–32). We assessed the expression of HDAC6 by western blot analysis on two different CCA cell lines (Hucct-1 and KMCH) and found increased expression in both (on average, 100%) of HDAC6 compared to normal cultured cholangiocytes (H69). Overexpression of HDAC6 correlated with the decreased amount of its target, acetylated α-tubulin (Figure 3A) supporting the validity of our analyses. The mRNA level was analyzed by qRT-PCR and no significant differences were found (Figure 3B), suggesting a posttranscriptional regulatory pathway. Using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, we also observed that HDAC6 was overexpressed in liver specimens from 10 patients with CCA compared to 11 normals (Figure 3C). We found a similar situation when we stained the commercially available CCA tissue array (AccuMax Array A205(II), Supp. Figure 5).

Figure 3. HDAC6 expression in Cholangiocarcinoma.

A, Western blot analysis of HDAC6 protein expression showed increased levels in different tumor cell lines compared to control H69 cells. The upregulation of HDAC6 correlates with the decreased amount of acetylated α-tubulin. B, qRT-PCR showed no significant differences in the messenger level of HDAC6. C, Confocal immunofluorescence images for HDAC6 (green) on normal and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) human liver samples. Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI.

In order to assess the role of HDAC6 overexpression in cholangiocyte ciliary loss, we transfected NHC cells with a HDAC6-flag expression vector. Confocal immunofluorescences using anti-flag and HDAC6 antibodies demonstrated the expression of the HDAC6-flag construct (Figure 4A). As predicted, when the cells were co-stained with the ciliary markers, ac-α-tubulin and IFT88, the cells that were positive for the flag epitope showed reduced cilia expression compared with the surrounding non-transfected cells (Figure 4B). After stable transfected cells were obtained by antibiotic selection, western blot analysis demonstrated the overexpression of HDAC6 in the stably transfected cells using anti-flag antibodies (Figure 4C). In addition to the decreased ciliary expression (Figure 4D), these cells showed an increased proliferation rate (1.7-fold) (Figure 4E), increased anchorage-independent growth (1.5-fold) (Figure 4F), and decreased protein levels of acetylated-α-tubulin compared with empty vector transfected cells (Figure 4G). Taken together, these results suggest that the overexpression of HDAC6 in normal cholangiocytes correlates with the reduction of primary cilia expression and the acquisition of a malignant-like phenotype.

Figure 4. Effect of HDAC6 overexpression in normal cholangiocytes.

A, NHC cells were transfected with HDAC6-flag expression vector, and protein expression was analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence using anti-flag (green) and anti-HDAC6 antibodies (red); nuclei were stained in blue with DAPI. B, Confocal immunofluorescence using anti-flag (purple), anti-acetylated-α-tubulin (red) and anti-ift88 (green) showed that cells overexpressing HDAC6 do not grow cilia compared with non-transfected surrounding cells. C, NHC cells were stably transfected with empty vector or with HDAC6-flag expression vector. Western blots analysis showed the expression of HDAC6-flag. D, confocal immunofluorescence on cells cultured 2 days in cilia promoting media showed ciliary expression by acetylated-α-tubulin staining (red) and centrioles (purple). Note that cilia are easily detected by the basal bodies in empty vector transfected cholangiocytes (EV) while they are mainly absent on the HDAC6-flag transfected cells. Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI. E, MTS proliferation assay comparing empty vector (EV) and HDAC6-flag stably transfected cells (p<0.05). F, Colony number after 14 days of growth in soft agar (p<0.05). G, Western blot analysis of acetylated-a-tubulin on NHC cells stable transfected with EV and HDAC6-flag.

Targeting HDAC6 induces ciliary restoration and reverses the malignant phenotype of CCA cells

Since HDAC6 overexpression seems to contribute importantly to CCA ciliary lost, we inhibited HDAC6 expression by specific shRNAs (Figure 5A), or with the HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin-A(33). These approaches both induced an increase in acetylated-α-tubulin levels, and the restoration of primary cilia expression in the CCA cell lines (3.3 and 18 –fold, respectivelly) (Figure 5A, D, and E); and the restoration of primary cilia correlated with downregulated Hh and MAPK signaling pathways (Figure 5C), as well as decreased cell proliferation rates (decresed in average by 50%) (Figure 5B and F) and invasion (decreased by 40%) (Figure 5G). To analyze if the restoration of cilia is a major reason for these phenotypic changes, we repeated the experiments in KMCH cells stably transfected with IFT88-shRNA to prevent ciliogenesis. In the experiments in which CCA cells were prevented from developing cilia, the proliferation rates and anchorage-independent growth rates were not significantly different from the vehicle-treated cells (Figure 6A and B), showing that the ability of cells to undergo ciliogenesis is essential for the effects of tubastatin-A. These data are consistent with a critical role of HDAC-6 in reduced ciliogenesis in CCA cells and provide further support for a relationship between the absence of cilia and a malignant phenotype.

Figure 5. Targeting of HDAC6 induces cilia restoration in tumor cells.

A, CCA cells were stably transfected with HDAC6 specific or with a non-target control (NT) shRNAs. HDAC6 and acetylated-α-tubulin protein expression was analyzed by western blot. Ciliary expression was analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence. The ciliary marker, acetylated-α-tubulin in red; the centrioles marker γ-tubulin in green; and nuclei were stained with DAPI in blue. B, Proliferation analysis by MTS (p<0.001). C, MAPK and Hh signaling pathways were analyzed by western blots of pERK and Gli1, respectively. D, CCA cells were treated for 2 days in ciliary promoting media in the absecence or presence of the HDAC6 inhibitor tubastatin-A. Acetylated-α-tubulin protein expression was analyzed by western blot (D), and the expression of cilia was analyzed by confocal microscopy (E). Cilia are stained in red with the ciliary marker IFT88 and nuclei in blue with DAPI. F, Tubastatin-A treatment reduced proliferation rates in two different CCA cell lines (*p<0.05). G, Invasion assays comparing vehicle treated (control) and tubastatin-A treated KMCH cells (*p<0.05).

Figure 6. HDAC6 inhibition by Tubastatin-A decreased proliferation and anchorage independent growth in a ciliary dependent manner.

KMCH cells stably transfected with NT or IFT88 shRNA were incubated in the presence or absence of tubastatin-A and proliferation by cell counting (A) and anchorage independent growth (B) were assessed.

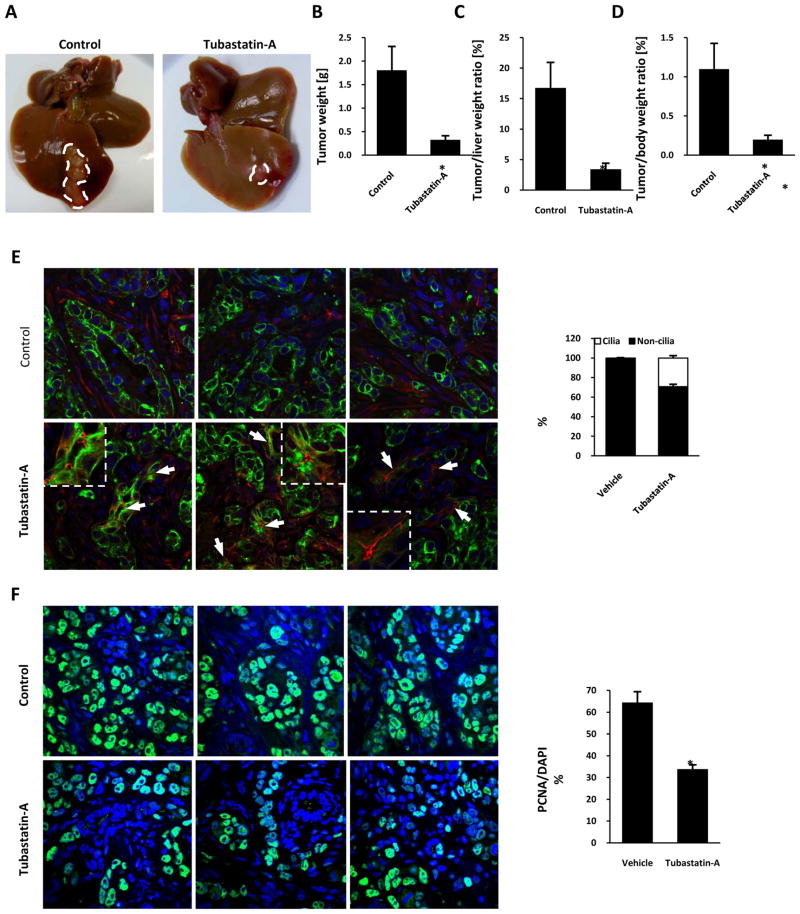

HADC6 inhibition by tubastatin-A treatment reduces tumor growth and induces ciliogenesis in vivo

Based on the in vitro activity of tubastatin-A on CCA cell lines, we tested the effect of this drug using a recently developed syngeneic rat orthotopic model of CCA (21, 27, 28). Tumors were removed after treatment with tubastatin-A or vehicle for 7 days. The mean tumor weights in animals treated with tubastatin-A was 6-fold lower than vehicle-treated controls (0.33 ± 0.09 vs. 1.81 ± 0.51 g, P<0.05), and the ratios of tumor weight to liver weight and body weight were also significantly reduced (5-and 5.6-fold, respectively) by tubastatin-A treatment (Figure 7A, B, C, D). Furthermore, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy showed a greater frequency of ciliated cholangiocytes in the treated animals compared with controls (29% vs 1.4% ciliated cells per high power field) (Figure 7E, G). Finally, the amount of PCNA positive cells were significantly reduced in the treated tumors compared with vehicle controls (34% vs 65% PCNA positive cells per high power field), indicating decreased proliferation (Figure 7F, H). These data indicate that a drug that inhibits HDAC6 can significantly reduce the growth of CCA in vivo.

Figure 7. Effect of tubastatin-A on cholangiocarcinoma growth in vivo.

The effect of tubastatin-A was tested on an orthotopic, syngeneic CCA model in rats. A, Livers were removed after 7 days of treatment and tumors were dissected. Tumor weights, tumor/liver weight, and tumor/body weight ratios were calculated and compared (B–D). Tumor sections were stained with the ciliary marker acetylated-α-tubulin in red and the cholangiocyte marker CK-7 in green (E), or with the proliferation marker PCNA in green (F), nuclei were stained in blue with DAPI. The amount of ciliated and PCNA positive cells per field were quantificated (G, H). (*p<0.05, n=5 for controls and n=6 for tubastatin-A).

DISCUSSION

The key findings reported here relate to the potential role of primary cilia in the pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. Our data show that: i) the expression of primary cilia is decreased in CCA in vivo and in vitro; ii) chemical or molecular deciliation of normal cholangiocytes induces a malignant phenotype characterized by increased proliferation, anchorage independent growth, invasion and activation of Hh and MAPK signaling pathways; iii) HDAC6 is overexpressed in CCA in vivo and in vitro; (iv) molecular overexpression of HDAC6 causes decreased ciliogenesis and induces proliferation, and anchorage independent growth in normal cholangiocytes (i.e., a malignant phenotype); (v) molecular downregulation of HDAC6 or its pharmacological inhibition by tubastatin-A induces restoration of primary cilia in CCA cells and reduces cell proliferation, anchorage-independent growth and invasion in a ciliary dependent manner, and vi) the HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin-A, reduces tumor growth in a CCA animal model. The data are consistent with an important role for HDAC6 and primary cilia in the pathogenesis of CCA.

Recently, four different tumors were described to be devoid of primary cilia. In pancreatic cancer cells, the absence of cilia is independent of ongoing proliferation and ciliogenesis can be reversed by inhibiting Kras pathways(2). These findings are consistent with our results since HDAC6 is activated by Kras and the incidence of Kras mutations in CCA is estimated to be 54–67% (3, 34). The absence of primary cilia has also been reported in sporadic clear cell renal carcinoma; in this case, ciliary loss is mediated by dysfunction of the protein of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene, pVHL(6). pVHL binds and stabilizes microtubules by protecting them from depolymerization, which is a prerequisite for ciliogenesis (6). Interestingly, pVHL inactivation induces HEF1 and AuroraA(35), and these events lead to HDAC6 activation and ciliary resorption(3). Aberrant ciliogenesis is also found in cells derived from astrocytomas/glioblastomas; it has been proposed that this deficiency likely contributes to the phenotype of these malignant cells(9). Finally, primary cilia are decreased in breast cancer as well, by unknown mechanisms(10). Taken together, our results and these previous studies suggest that the loss of primary cilia is a common feature in many epithelial tumors. However, our studies are the first to demonstrate the reduction of cilia and the overexpression of HDAC6 in CCA. Moreover, our data are first to demonstrate that restoration of primary cilia by targeting HDAC6 is a potential therapeutic approach for CCA and perhaps other tumors characterized by defective ciliogenesis.

On the other hand, the situation is different in medulloblastoma and basal cell carcinoma; these tumors are mainly ciliated and cilia are required for the growth of tumors bearing an activation mutation at the level of smoothened (ciliary dependent activator of the Hh signaling pathway). In contrast, if the tumors have an activation mutation of the downstream effector of the pathway, the transcription factor Gli2, primary cilia play a similar role as described in the present work, i.e. inhibition of tumor development(36, 37). In CCA, consistent with our results, the aberrant activation of Gli transcription factors has been described(38, 39).

HDAC6 is a unique member of the histone deacetylase family because, unlike other histone deacetylases, it does not interact with histones (i.e., inhibition of HDAC6 inhibits deacetylation of α-tubulin without affecting histone acetylation)(40). HDAC6 not only deacetylates α, tubulin but also cortactin, Hsp90 and the redox regulatory proteins, PrxI and II(41). Moreover, HDAC6 has been identified as a key regulator of many processess that are linked to cancer (e.g., cell survival, motility and metastasis), making it an attractive therapeutic target (40). Based on our results, it appears that the antitumorigenic effect of HDAC6 inhibition in CCA mainly depends on ciliary restoration, since KMCH cells stably transfected with ift88 shRNA did not respond to tubastatin-A treatment. We acknowledge that the involvement of the other targets of HDAC6 cannot be confidently excluded.

Previous work with embryonic kidney cells, mammary epithelial cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and ovarian and cancer cell lines, showed that HDAC6 is not only important for Ras- or ErbB2-dependent oncogenic transformation of primary cells but is also required for maintaining the anchorage-independent growth of established cancer cell lines(29). The exact molecular mechanisms mediating such a tumor-promoting effect remains unknown. Our results in CCA cells suggest that HDAC6 mediates the oncogenic-induced loss of primary cilia and the subsequent derepression of tumorigenic signaling pathways like Hh and MAPK. The mechanisms by which HDAC6 is overexpressed in CCA remain to be elucidated. Since we found alterations in protein but not mRNA levels for HDAC6, post-translational regulations (e.g., HCAC6 turnover rates, the downregulation of microRNAs potentially targeting HDAC6 mRNA, etc), are possibilities.

Hedgehog and ERK1/2 pathways are both activated in CCA (38, 39, 42) and the dual targeting of these pathways coordinately decrease proliferation and survival of CCA cells (42). IL6 and bcl-2, both targets of hedgehog signaling (43–45), are also activated in CCA (46, 47). Our results show that the experimental deciliation of normal cholangiocytes induced the activation of both, hedgehog and MAPK pathways, consistent with the concept that cilia normally act as a negative regulator of these pathways in cholangiocytes. Importantly, our results also show that the restoration of primary cilia, by targeting HDAC6 in CCA cells, decreases Hh and MAPK signaling pathways.

Michaud and Yoder speculated that genes and proteins involved in the structure or function of primary cilia may represent new targets for small-molecule inhibitors, small interfering RNAs, or antibody therapeutics (48). Based on our data, we would extend this concept by suggesting that restoration of primary cilia and their complex multisensory signals by HDAC6 targeting could act as a tumor suppressor mechanism. Indeed, the rapidly evolving field of HDAC inhibitors promises to generate very potent and specific HDAC6 inhibitors, like tubastatin-A (33) and the more recently developed ACY-1215 (49). The fact that mice lacking HDAC6 are viable and develop normally (50) suggests that HDAC6 specific targeting may have minimal adverse effects. Furthermore, our in vivo experiments on a rat CCA model using tubastatin-A showed a significant decrease in tumor growth associated with an increased ciliary expression, suggesting that the restoration of primary cilia in tumor cells by means of HDAC6 inhibitors may be a potential therapeutic approach for CCA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by a Pilot and Feasibility Award to SAG from the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (P30DK084567), a Wendy Will Case Cancer Fund Award to SAG, a Mayo Clinic Cancer Center Eagle Fellowship to SAG, a R01 DK24031 to NFL, and the Mayo Foundation.

We thank Drs. Tetyana Masyuk, Anatoliy Masyuk, Steven O’Hara and Patrick Splinter for insightful discussions and Drs. Gregory Gores and Martin Fernandez-Zapico for carefully reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Satir P, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. The primary cilium at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:499–503. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeley ES, Carriere C, Goetze T, Longnecker DS, Korc M. Pancreatic cancer and precursor pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesions are devoid of primary cilia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:422–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugacheva EN, Jablonski SA, Hartman TR, Henske EP, Golemis EA. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell. 2007;129:1351–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowers AJ, Boylan JF. Nek8, a NIMA family kinase member, is overexpressed in primary human breast tumors. Gene. 2004;328:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutz MS, Burk RD. Primary cilium formation requires von hippel-lindau gene function in renal-derived cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6903–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schraml P, Frew IJ, Thoma CR, Boysen G, Struckmann K, Krek W, et al. Sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma but not the papillary type is characterized by severely reduced frequency of primary cilia. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:31–6. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, Seeley ES, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB, et al. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:709–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isfort RJ, Cody DB, Doersen CJ, Richards WG, Yoder BK, Wilkinson JE, et al. The tetratricopeptide repeat containing Tg737 gene is a liver neoplasia tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 1997;15:1797–803. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser JJ, Fritzler MJ, Rattner JB. Primary ciliogenesis defects are associated with human astrocytoma/glioblastoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan K, Frolova N, Xie Y, Wang D, Cook L, Kwon YJ, et al. Primary Cilia Are Decreased in Breast Cancer: Analysis of a Collection of Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 58:857–70. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.955856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzioni M, Invernizzi P, Candelaresi C, Maggioni M, Saccomanno S, Selmi C, et al. Human cholangiocarcinoma development is associated with dysregulation of opioidergic modulation of cholangiocyte growth. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis H, Alpini G, DeMorrow S. Recent advances in the regulation of cholangiocarcinoma growth. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00114.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masyuk AI, Huang BQ, Ward CJ, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Masyuk TV, et al. Biliary exosomes influence cholangiocyte regulatory mechanisms and proliferation through interaction with primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00093.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masyuk AI, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Lee SO, et al. Cholangiocyte primary cilia are chemosensory organelles that detect biliary nucleotides via P2Y12 purinergic receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G725–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gradilone SA, Masyuk AI, Splinter P, Banales JM, Huang B, Tietz P, et al. Cholangiocyte cilia express TRPV4 and detect changes in luminal tonicity inducing bicarbonate secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705964104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:911–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Hara SP, Splinter PL, Trussoni CE, Gajdos GB, Lineswala PN, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte N-Ras protein mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin 6 secretion and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30352–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banales JM, Saez E, Uriz M, Sarvide S, Urribarri AD, Splinter P, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA 506 leads to decreased Cl(−)/HCO(3) (−) anion exchanger 2 expression in biliary epithelium of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hep.25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyagiwa M, Ichida T, Tokiwa T, Sato J, Sasaki H. A new human cholangiocellular carcinoma cell line (HuCC-T1) producing carbohydrate antigen 19/9 in serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989;25:503–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02623562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami T, Yano H, Maruiwa M, Sugihara S, Kojiro M. Establishment and characterization of a human combined hepatocholangiocarcinoma cell line and its heterologous transplantation in nude mice. Hepatology. 1987;7:551–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirica AE, Zhang Z, Lai GH, Asano T, Shen XN, Ward DJ, et al. A novel “patient-like” model of cholangiocarcinoma progression based on bile duct inoculation of tumorigenic rat cholangiocyte cell lines. Hepatology. 2008;47:1178–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.22088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai GH, Zhang Z, Shen XN, Ward DJ, Dewitt JL, Holt SE, et al. erbB-2/neu transformed rat cholangiocytes recapitulate key cellular and molecular features of human bile duct cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:2047–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Hara SP, Splinter PL, Gajdos GB, Trussoni CE, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Chen XM, et al. NFkappaB p50-CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta)-mediated transcriptional repression of microRNA let-7i following microbial infection. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:216–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischle W, Emiliani S, Hendzel MJ, Nagase T, Nomura N, Voelter W, et al. A new family of human histone deacetylases related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae HDA1p. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11713–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gradilone SA, Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Banales JM, Lehmann GL, Radtke BN, et al. Activation of Trpv4 reduces the hyperproliferative phenotype of cystic cholangiocytes from an animal model of ARPKD. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:304–14. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gradilone SA, Masyuk AI, Splinter PL, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Tietz PS, et al. Cholangiocyte cilia express TRPV4 and detect changes in luminal tonicity inducing bicarbonate secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705964104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smoot RL, Blechacz BR, Werneburg NW, Bronk SF, Sinicrope FA, Sirica AE, et al. A Bax-mediated mechanism for obatoclax-induced apoptosis of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1960–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fingas CD, Blechacz BR, Smoot RL, Guicciardi ME, Mott J, Bronk SF, et al. A smac mimetic reduces TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced invasion and metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2010;52:550–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.23729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YS, Lim KH, Guo X, Kawaguchi Y, Gao Y, Barrientos T, et al. The cytoplasmic deacetylase HDAC6 is required for efficient oncogenic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7561–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakuma T, Uzawa K, Onda T, Shiiba M, Yokoe H, Shibahara T, et al. Aberrant expression of histone deacetylase 6 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcus AI, Zhou J, O’Brate A, Hamel E, Wong J, Nivens M, et al. The synergistic combination of the farnesyl transferase inhibitor lonafarnib and paclitaxel enhances tubulin acetylation and requires a functional tubulin deacetylase. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3883–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haggarty SJ, Koeller KM, Wong JC, Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Domain-selective small-molecule inhibitor of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6)-mediated tubulin deacetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4389–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430973100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler KV, Kalin J, Brochier C, Vistoli G, Langley B, Kozikowski AP. Rational design and simple chemistry yield a superior, neuroprotective HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin A. J Am Chem Soc. 132:10842–6. doi: 10.1021/ja102758v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa D, Ojima H, Kokubu A, Ochiya T, Kasai S, Hirohashi S, et al. Vandetanib (ZD6474), an inhibitor of VEGFR and EGFR signalling, as a novel molecular-targeted therapy against cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1257–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Li H, Wang B, Xu Y, Yang J, Zhang X, et al. VHL inactivation induces HEF1 and Aurora kinase A. J Am Soc Nephrol. 21:2041–6. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han YG, Kim HJ, Dlugosz AA, Ellison DW, Gilbertson RJ, Alvarez-Buylla A. Dual and opposing roles of primary cilia in medulloblastoma development. Nat Med. 2009;15:1062–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong SY, Seol AD, So PL, Ermilov AN, Bichakjian CK, Epstein EH, Jr, et al. Primary cilia can both mediate and suppress Hedgehog pathway-dependent tumorigenesis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1055–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurita S, Mott JL, Cazanave SC, Fingas CD, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, et al. Hedgehog inhibition promotes a switch from Type II to Type I cell death receptor signaling in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurita S, Mott JL, Almada LL, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Sun SY, et al. GLI3-dependent repression of DR4 mediates hedgehog antagonism of TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2010;29:4848–58. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldana-Masangkay GI, Sakamoto KM. The role of HDAC6 in cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011:875824. doi: 10.1155/2011/875824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parmigiani RB, Xu WS, Venta-Perez G, Erdjument-Bromage H, Yaneva M, Tempst P, et al. HDAC6 is a specific deacetylase of peroxiredoxins and is involved in redox regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9633–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803749105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jinawath A, Akiyama Y, Sripa B, Yuasa Y. Dual blockade of the Hedgehog and ERK1/2 pathways coordinately decreases proliferation and survival of cholangiocarcinoma cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:271–8. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0166-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elsawa SF, Almada LL, Ziesmer SC, Novak AJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM, et al. GLI2 transcription factor mediates cytokine cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:21524–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bigelow RL, Chari NS, Unden AB, Spurgers KB, Lee S, Roop DR, et al. Transcriptional regulation of bcl-2 mediated by the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway through gli-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:1197–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu XF, Guo CY, Liu J, Yang WJ, Xia YJ, Xu L, et al. Gli1 maintains cell survival by up-regulating IGFBP6 and Bcl-2 through promoter regions in parallel manner in pancreatic cancer cells. J Carcinog. 2009;8:13. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.55429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wehbe H, Henson R, Meng F, Mize-Berge J, Patel T. Interleukin-6 contributes to growth in cholangiocarcinoma cells by aberrant promoter methylation and gene expression. Cancer research. 2006;66:10517–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harnois DM, Que FG, Celli A, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. Bcl-2 is overexpressed and alters the threshold for apoptosis in a cholangiocarcinoma cell line. Hepatology. 1997;26:884–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. The primary cilium in cell signaling and cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6463–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santo L, Hideshima T, Kung AL, Tseng JC, Tamang D, Yang M, et al. Preclinical activity, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic properties of a selective HDAC6 inhibitor, ACY-1215, in combination with bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:2579–89. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Kwon S, Yamaguchi T, Cubizolles F, Rousseaux S, Kneissel M, et al. Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1688–701. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01154-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.