Abstract

Background:

Periodontal debridement has an impact on the vascular thrombotic markers in healthy individuals. This study aimed to investigate changes in several vascular thrombotic markers after surgical and non-surgical periodontal debridement in hypertensives with periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

40 hypertensives, 27 males and 13 females, 37-68 year old, mean 51.2 years, with moderate to severe periodontitis, were divided into two groups, (n = 20 for each); the first received comprehensive one session non-surgical periodontal debridement, (pockets 4-6 mm), while the second received comprehensive supragingival scaling with surgical debridement at one quadrant, (Pockets > 6 mm). Periodontal parameters included; plaque index (PI), gingival inflammation (GI), bleeding on probing (BOP), pocket probing depth (PPD). Vascular thrombotic tests included; platelets count (Plt), fibrinogen (Fib), Von Willebrand factor antigen activity (vWF:Ag), and D-dimers (DD).

Results:

PI, GI, BOP, PPD, decreased significantly (P = 0.001) after 6 weeks of periodontal debridement in both groups, while BOP and PPD remained higher in the surgical one (P < 0.05). Thrombotic vascular markers changes through the three-time intervals were significant in each group (P = 0.001), and time-group interception effect was significant for vWF:Ag (P = 0.005), while no significant differences between groups after treatment (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Periodontal debridement, surgical and non-surgical, improved the periodontal status in hypertensives. Periodontal treatment activated the coagulation system in hypertensives and recessed later while the treatment modality did not affect the degree of activation.

Keywords: Hypertension, periodontitis, periodontal debridement, vascular thrombotic markers

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis has been described as a probable risk factor for evoking a procoagulant state mediated by periodontal pathogens and its bioactive products,[1] which contributes to an induction of a low-grade systemic inflammation that complies with a transient repeated bacteremia.[2] On the other hand, endothelial dysfunction and hypercoagulability are thought to be a result of the concomitant involvement of hypertension and the physical friction of blood on the vascular wall. Apparently, the activation of platelets and the endothelial cells is reflected by an increase in the plasmatic vascular and thrombotic markers, for example, platelets count (Plt), fibrinogen (Fib), von Willebrand factor antigen activity (vWF:Ag) and D-dimers (DD).[3,4,5] Periodontal debridement itself has been assumed to induce additional transient bacteraemia through the concomittant traumatic procedures.[6,7,8] The aim of this study was to assess changes in blood levels of several vascular thrombotic markers; platelets count, Fib, vWF:Ag and the DD, accompanying surgical and non-surgical periodontal debridement in hypertensive patients with periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and general examination

A total of 40 consecutive patients, 27 males and 13 females, aged 37-68 years old, (mean 51.2 years), of whom recalled the department of periodontology, faculty of dental surgery at Damascus University from March 2010 to April 2010, met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate signing an informed written consent. They were non-smokers, had more than 20 teeth, did not have any coagulopathies or metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia) or any periodontal treatment or extractions during the last 6 months or any antibiotic therapy for 3 months or corticosteroids for the last year. Pregnant and breast feeding women, uncontrolled hypertensive (systolic blood pressure [SBP] >160 mm/Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm/Hg) and body mass index >31 were excluded.[9,10] Personal information, medical history and blood pressure mean value before treatment were also registered. Hypertension was diagnosed depending on the medical history and checking the current blood pressure as patients were on different antihypertensive agents (Losartan*, Deltiazim*, Metoprolol*, Amlodepin*).[11]

Periodontal disease was diagnosed depending on the existence of 4 teeth or more with one site or more in which pocket probing depth (PPD) ≥4 mm and/or clinical attachment loss ≥3 mm.[12] Accordingly, the study population was distributed into two groups: Non-surgical group with pockets 4-6 mm, 12 males and 8 females and surgical group, pockets >6 mm, 15 males and 5 females. The scientific research board and Ethical Committee of Damascus University approval was obtained with the primary project plan.

Periodontal examination

All patients had generalized chronic periodontitis with mean PPD >4 mm.[13] Periodontal indices included Plaque index (PI), gingival inflammation (GI), bleeding on probing (BOP) and PPD, were measured by a trained examiner taking four-site registration (midfacial, mesial, distal and lingual/palatal) by means of University of North Carolina-15 periodontal probe, (Medesy-Italy).[14,15] Panoramic radiographs were taken to assess the intensity and type of bony defects.

Periodontal debridement procedures

Non-surgical mechanical debridement consisted of one session full mouth scaling and root planning under local anesthesia as required using ultrasonic instruments, (Satelec-Switzerland) and was accomplished by Gracey's manual instrumentation, (LASCAD/Zeffiro-Italy). Surgical group received full mouth supragingival scaling with Widman flap reflected at one quadrant, mechanical debridement without any chemical conditioning, flap reduction and 4/0 silk interrupted suturing.[16] Actual working time was registered for each patient at the end of the treatment session.

Laboratory biochemical tests

Blood samples, 20 ml, were collected from the antecubital veins of all patients after 16 h of fasting at the first visit for baseline, by the same patient-status-blinded technician. Blood samples were distributed into two types of tubes; the first contained ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for general blood chemistry tests; (cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose fasting, (Chemistry analyzer AU 400-life and material science-Germany), and complete blood count and platelets (ref. interval 150-400 × 103/mm3), (ABX-5 Pentra-60, Horiba ABX-France), while the second and the third tubes contained sodium citrate 3.8% for the coagulation tests (Clotting analyzer CoaDATA 2001, Labitech-Germany); Fib, (ref. interval Clauss 200-400 mg/dL), vWF:Ag, (ref. interval 100%), (Hitachi 911, Roche-Diagnostics, U.S.A) and D-Dimers, (ref. interval 0.05 ΅g FEU/mL), (AU400 Olympus). All tests were performed at the Police Hospital central lab while vWF:Ag test was performed at the laboratories Department of Al-Assad Hospital, Damascus University. Plasma samples were refrigerated at −56°C until the coagulation tests were performed.[17,18,19]

Follow-up

Chlorhexidine 0.12% mouth rinses were prescribed and sutures removal after 7 days with a weekly recall.[16,20] A second periodontal parameters determination was performed after 6 weeks for each patient while blood samples were re-collected after 48 h and after 6 weeks of treatment.

Statistical study

Independent t-test was used to study the differences in variables between the treatment groups and paired samples t-test to study differences in each group before and after periodontal treatment. General linear model ANOVA analysis for repeated measures was applied to study the significance of the thrombotic variables changes through the three-time intervals, as well as the effect of interaction between time and group for each variable. All tests were performed at 5% of confidence level, SPSS 19th edition software (Chicago, IL, USA).[21]

RESULTS

General examination

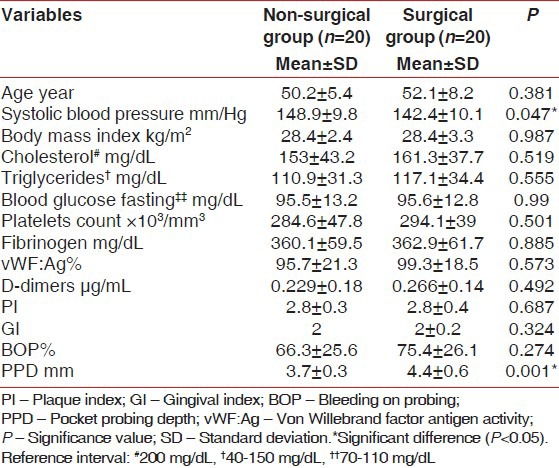

Statistical study showed higher SBP mean value at baseline in the non-surgical group compared with the surgical one (P = 0.047) [Table 1]. There was no statistically significant differences in age, body mass index, cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose fasting (P > 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Means of variables in the non-surgical and before periodontal debridement (baseline) surgical groups (n=40)

Periodontal parameters

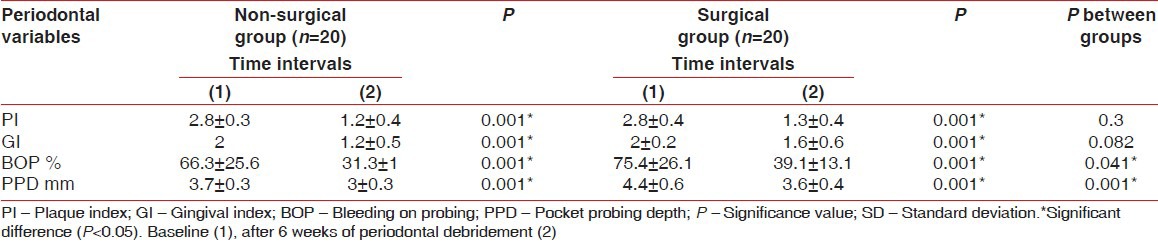

PPD was higher at baseline in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical one, (P = 0,001), [Table 1]. The periodontal indices decreased significantly after 6 weeks in both groups (P = 0.001), [Table 2] despite of the fact that BOP and PPD values remained higher in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical one (P = 0.041-0.001 respectively), [Table 2]. Working time was significantly higher in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical (40.2 ± 5.1 vs. 74.3 ± 10.4, respectively P = 0.001). (Not mentioned in tables).

Table 2.

Means of periodontal indices in the non-surgical and surgical groups

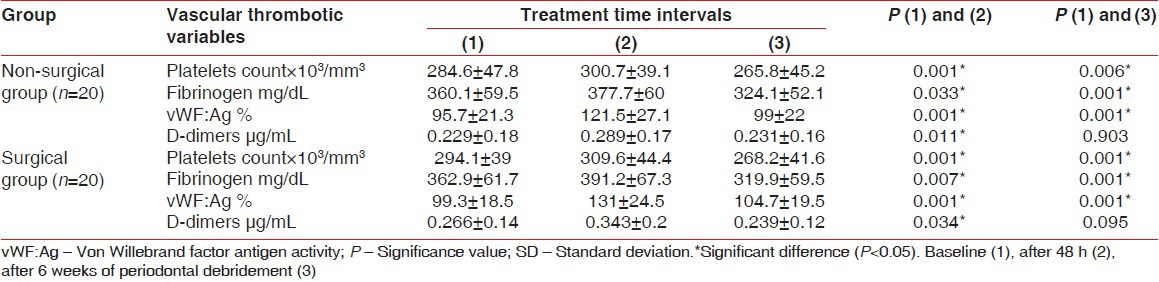

Vascular thrombotic markers

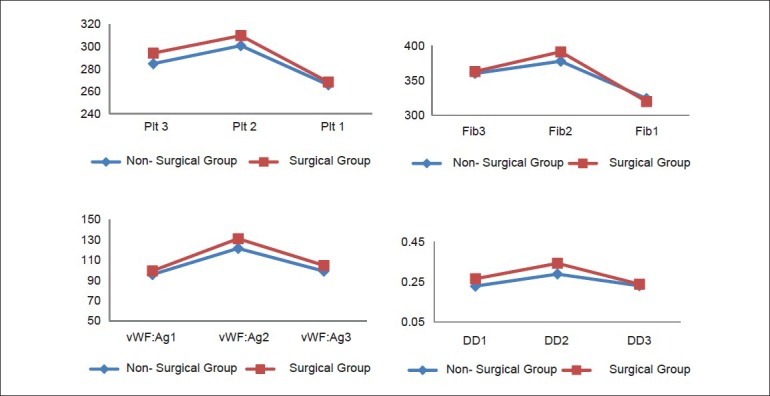

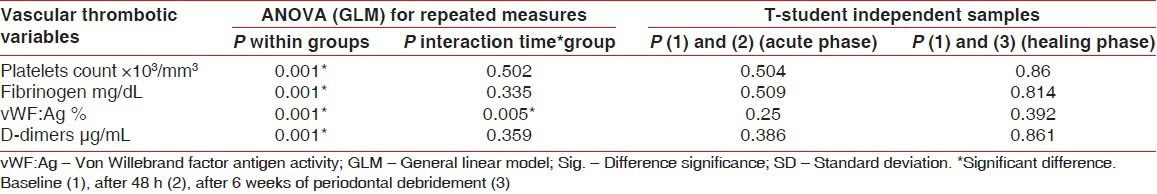

No significant differences appeared between groups regarding vascular thrombotic variables at baseline, (P > 0.05), [Table 1]. Nonetheless, all vascular thrombotic markers levels increased significantly after 48 h in both groups (P < 0.05), [Table 3]. After 6 weeks, Plt and Fib decreased significantly while vWF:Ag sustained higher than baseline, (P < 0.05) and DD restored approximately baseline, (P > 0.05), [Table 3, Figure 1]. No significant differences were noticed between the two groups after 48 h and 6 weeks, (P > 0.05), [Table 4]. However, ANOVA General linear model test revealed significant changes through the three-time interval within each group, (P = 0.001) and a significant effect of interaction between time and group for vWF:Ag, (P = 0.005), [Table 4].

Table 3.

Means of vascular thrombotic markers in the non-surgical and surgical groups

Figure 1.

Changes in vascular thrombotic markers across the three-time intervals

Table 4.

ANOVA test for vascular thrombotic markers changes across time intervals within the two groups and the t test results for acute and healing phases

DISCUSSION

Statistical study revealed groups homogeneity regarding age, gender and body mass index (P > 0.05) while higher blood pressure in the non-surgical group compared with surgical one (148.9 ± 9.8 vs. 142.4 ± 10.1 mm/Hg, respectively, P = 0.047), which might be contributed to coincidence or the small size of population and groups. Ageing was described as a common risk factor for chronic periodontitis and hypertension as both diseases have a middle age predilection, bearing in mind that age and gender are determinant factors that cannot be modified with the fact of lower healing responses are assumed in males and females older than 40 years.[11,22] Angeli et al.,[23] suggested a direct association between periodontitis and the left ventricular volume in hypertensives. Völzke et al.[24] also reported that blood pressure was higher in individuals who had 0 to 6 teeth in their mouth compared with those who had 27-28 teeth. Recent reports have pointed out that ageing is accompanied by changes at the hemostatic level presented with hypercoagulability.

Cholesterol, triglycerides and blood glucose fasting levels in both groups were comparable (P > 0.05) and within the reference interval, Table 1, which negates the metabolic syndrome existence in our study population. However, Benguigui et al.[25] revealed an association between the Metabolic syndrome, especially increased insulin resistance and severe periodontitis. Moreover, Oz et al.[26] reported that the systemic inflammation in periodontitis is accompanied with dyslipidemia, which improved after periodontal treatment.

PPD was higher in the surgical group at baseline (4.4 ± 0.6 vs. 3.7 ± 0.3 mm, respectively, P = 0.001). Nevertheless, after 6 weeks of periodontal treatment all periodontal parameters improved in each group (P < 0.05). However, both of BOP and PPD remained higher in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical (39.1 ± 13.1 vs. 31.3 ± 1%, P = 0.041), (3.6 ± 0.4 vs. 3 ± 0.3 mm, P = 0.001) respectively. Oral hygiene instructions and periodontal treatment, after different follow-up periods extended from 6 weeks to 6 years, lead to an improvement in periodontal indices such as Plaque index, gingival inflammation, Pocket probing depth and clinical attachment loss, regardless of the treatment modality.[27] The differences in the healing degree reflect a difference in the healing volume depending on the initial pocket depth when it is ≥7 mm.[28,29] Considering that our study population individuals were administering a wide-spectrum of antihypertensive agents, which may influence the periodontal disease process,[30] since the results of our previous study comparing hypertensives on antihypertensive agents with normotensives as higher values in PPD (4.1 ± 0.6 vs. 3.75 ± 0.55 respectively, P = 0.008) and clinical attachment loss (3.3 ± 0.93 vs. 2.31 ± 1.43, respectively, P = 0.001).[31]

Despite of the difference in pockets depth and the periodontal disease intensity, there were no statistically significant differences in vascular thrombotic markers between the two groups at baseline, (P > 0.05).

Platelets count increased after 48 h of treatment in both groups and decreased after 6 weeks (P < 0.05), with no significant differences between the two groups at both time intervals, (P > 0.05). These findings comply with the study of Balwant et al.[32] on 26 healthy patients aged 30-65 years with severe periodontitis, PPD > 6 mm, reporting that Plt count decreased significantly after 10 weeks of scaling and root planning (245 vs. 223 × 103/mm3) as it has been assumed that platelets have a role in the inflammatory process through adhesion and aggregation. Platelets are activated in hypertension[4] and in our previous study on 80 patients with periodontitis, Plt count was higher in the hypertensive group compared with those with periodontitis alone (266 ± 43.5 vs. 289.3 ± 43.6 respectively, P = 0.022).[31] On the other hand, other studies[33,34] on the effect of periodontal treatment on vascular thrombotic markers in healthy individuals with periodontitis, reported a significant increase in Plt count after 48 h in the non-surgical group compared with the surgical one in addition to a significant time group interaction (P = 0.001), which might be attributed to the extension of working surface. However, Plt count values decreased significantly after 6 weeks in both groups.

Fib levels increased after 48 h in both groups and decreased after 6 weeks (P < 0.05), with no significant differences between groups at both time intervals, (P > 0.05). Our results agreed with many studies. D’Aiuto et al.[35] reported that intensive periodontal treatment in severe periodontitis was accompanied with an increase in Fib levels, which peaked after 24 h and decreased significantly after 30 weeks while Balwant et al.[32] marked this decrease after 10 weeks. Vidal et al.[36] suggested that non-surgical periodontal treatment was effective in improving BOP and PPD indices and in reducing inflammatory markers interleukin-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), including Fib in severe periodontally diseased hypertensives. In contrast, Radafshar et al.[37] did not find a significant decrease in Fib levels after 1 week and after 3 months following mechanical periodontal treatment in severe periodontitis, even though there was a significant decrease in CRP and white blood cell count.

vWF:Ag activity increased significantly in both groups after 48 h (P < 0.05) and it decreased after 6 weeks retaining higher values in comparison to baseline with no significant differences between groups at both time intervals, (P > 0.05). Nonetheless, despite there was no statistical significant difference between the two groups at baseline, ANOVA test showed a significant effect of interaction of time group, (P < 0.05). This outcome would be attributed to the intensity of periodontal disease in the surgical group compared to the non-surgical one represented by the deeper PPD (4.4 ± 0.6 vs. 3.7 ± 0.3 respectively, P = 0.001). These results may enhance the suggestion that poor oral hygiene is accompanied with increased levels of Von Willebrand factor.[10] Tonetti et al.[38] reported that vWF:Ag activity was higher in the intensive group after 24 h of treatment compared to multi-sessions. Furthermore, D’Aiuto et al.[7] mentioned that intensive treatment was accompanied with a mild inflammatory response, 30% higher than baseline, which persisted for 1 week. It was also associated with clear endothelial cell activating during 30 day, adding that population contained smokers as smoking had influenced the acute release of the bioactive markers.

Likewise, DD levels raised after48 h in both groups (P < 0.05) and decreased after 6 weeks, with no significant differences between groups at both time intervals, (P > 0.05). Endothelial surface coursing as noticed in atherosclerosis, trauma and infection, would initiate thrombosis.[39] D’Aiuto et al.[2] postulated that intensive periodontal treatment evoked changes at the hemostatic system plane manifested by an increase in DD level, which peaked after 24 h and resettled within 1 month. Graziani et al.[34] mentioned that non-surgical periodontal treatment in systemic healthy individuals lead to a significant increase in DD levels after 24 h, which was more evident in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical. Controversially, Montebugnoli et al.[40] did not find any significant differences before and after periodontal treatment regarding DD in patients exhibiting periodontitis with coronary heart disease.

Small size of population formed a limitation of this study, but the overall data might infer that both modalities of periodontal treatment had induced, after 48 h, a mild activation of several thrombotic system mediators presenting a procoagulatory state, even though not exceeding the normal range of values, which recessed within 6 weeks. Despite of the longer operating time in the surgical group, the degree of changes was close in both groups.

According to the chronic nature of both periodontitis and hypertension, the periodontal intervention, when one of the two diseases exists or both do, may not decrease the symptoms or lower the risk of future thrombotic events, but it may augment the overall prophylactic circumstances to decrease this risk by introducing better oral hygiene and the suitable intervention. This might be supported by systemic antibiotics and anti- inflammatory agents that lower the microbial and inflammatory burden, that's why development of new anticoagulants or antithrombotics that reduce the contribution of the inflammatory reaction to the vascular thrombotic disease is being warranted.[41] Data presented in this study may subject using the adjunctive therapies such as systemic antibiotics and justifies not interrupting platelets antagonists prescribed for hypertensive.

CONCLUSIONS

Periodontal debridement, surgical and non-surgical, has improved the periodontal status in hypertensives. Periodontal treatment activated the coagulation system in hypertensives and recessed later while the treatment modality did not affect the degree of activation. Ultimately, more studies are suggested to investigate the effect of periodontal disease and its treatment, in healthy and systemically diseased individuals, on the overall coagulation activation process output which is presented by thrombin activation using advanced thrombin generation assays such as the calibrated automated thrombogram that would help in assessing additional meticulous markers such as the microparticles levels that play, like thrombin, a role in both of the inflammatory and coagulation process, which would enhance more strict prophylactic procedures when treating health-compromised individuals.[42,43]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Talal Jarrouje MD., Haytham Fawal MD., Mazen Moghrabi DDS., MSc, Ousama Dieri DDS., Samer Arous MD., MSc. at the medical services administration and police hospital for facilitating administrative correspondences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Tayebb W. PhD, Thesis. Damascus: University of Damascus; 2007. Evaluating periodontitis role as a risk factor in atherosclerosis; pp. 120–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Andreou G, Suvan J, Brett PM, Ready D, et al. Periodontitis and systemic inflammation: Control of the local infection is associated with a reduction in serum inflammatory markers. J Dent Res. 2004;83:156–60. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bautista LE, Vera LM, Arenas IA, Gamarra G. Independent association between inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha) and essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:149–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lip GY. Hypertension, platelets, and the endothelium: The “thrombotic paradox” of hypertension (or “Birmingham paradox”) revisited. Hypertension. 2003;41:199–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049761.98155.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe GD. Measurement of thrombosis and its prevention. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:96–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asi KS, Gill AS, Mahajan S. Postoperative bacteremia in periodontal flap surgery, with and without prophylactic antibiotic administration: A comparative study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:18–22. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.65430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Tonetti MS. Acute effects of periodontal therapy on bio-markers of vascular health. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:124–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying Ouyang X, Mei Xiao W, Chu Y, Ying Zhou S. Influence of periodontal intervention therapy on risk of cardiovascular disease. Periodontol 2000. 2011;56:227–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bizzarro S, van der Velden U, ten Heggeler JM, Leivadaros E, Hoek FJ, Gerdes VE, et al. Periodontitis is characterized by elevated PAI-1 activity. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:574–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: An update on the associations and risk. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:362–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topol EJ, Califf RM. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Textbook of Vascular Medicine; pp. 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman M. Classification of diseases and conditions affecting the periodontium. In: Newman M, Palisano R, Carranza F, Taka H, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badersten A, Nilvéus R, Egelberg J. Scores of plaque, bleeding, suppuration and probing depth to predict probing attachment loss. 5 years of observation following non-surgicalperiodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:102–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joss A, Adler R, Lang NP. Bleeding on probing. A parameter for monitoring periodontal conditions in clinical practice. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:402–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson TG, Kornman KS. 2nd ed. U.K: Surrey, Quintessence; 2003. Fundamentals of Periodontics; pp. 330–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dacie S, Lewis B. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2001. Practical Haematology; pp. 353–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry JB. 20th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2001. Clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods; pp. 821–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewandrowski K. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Willkins; 2002. Clinical chemistry: Laboratory management and clinical correlations; pp. 365–74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL. Integration of plaque control into the practice of dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 1972;16:621–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman G, Streiner D. 3rd ed. Colorado, BC: Decker Inc; 2008. Biostatistics: The bare essentials; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maĭborodin IV, Pritchina IA, Gavrilova VV, Kolmykova IA, Kolesnikov IS, Sheplev BV. Periodontal tissues status after treatment of chronic periodontitis with consideration of gender and age. Stomatologiia (Mosk) 2008;87:31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Pellegrino C, Pellegrino RG, Pellegrino G, Prosciutti L, et al. Association between periodontal disease and left ventricle mass in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:488–92. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000056525.17476.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Völzke H, Schwahn C, Dörr M, Schwarz S, Robinson D, Dören M, et al. Gender differences in the relation between number of teeth and systolic blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1257–63. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234104.15992.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benguigui C, Bongard V, Ruidavets JB, Chamontin B, Sixou M, Ferrières J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and periodontitis: A cross-sectional study in a middle-aged French population. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:601–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oz SG, Fentoglu O, Kilicarslan A, Guven GS, Tanrtover MD, Aykac Y, et al. Beneficial effects of periodontal treatment on metabolic control of hypercholesterolemia. South Med J. 2007;100:686–91. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31802fa327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Shammari KF, Neiva R, Hill R, Wang H. Surgical and non-surgical treatment of chronic periodontal disease. Int Chin J Dent. 2002;2:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker B, Caffesse R, Ochsenbein C, Morrison E. Three modalities of periodontal therapy: II, 5-year final results. J Dent Res. 1990;69:219–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramfjord SP, Caffesse RG, Morrison EC, Hill RW, Kerry GJ, Appleberry EA, et al. 4 modalities of periodontal treatment compared over 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:445–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macovei G, Cotrutz C, Ursache M. Relationship aspects of general pathology and oral pathology in elderly patients. Ann RSCB. 2010;15:289–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.AlBush MM, Khattab R. Studying vascular thrombotic markers in chronic periodontitis with hypertension. J Damascus Univ Med Sci. 2011 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balwant R, Simmi K. Effect of scaling and root planning in periodontitis on peripheral blood. Int J Dent Sci. 2008;6:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.AlBush MM, Khattab R. Effect of non-surgical and surgical periodontal debridement on vascular thrombotic markers in chronic periodontitis. J Damascus Univ Med Sci. 2011 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graziani F, Cei S, Tonetti M, Paolantonio M, Serio R, Sammartino G, et al. Systemic inflammation following non-surgical and surgical periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:848–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Tonetti MS. Periodontal therapy: A novel acute inflammatory model. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:412–4. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vidal F, Figueredo CM, Cordovil I, Fischer RG. Periodontal therapy reduces plasma levels of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen in patients with severe periodontitis and refractory arterial hypertension. J Periodontol. 2009;80:786–91. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radafshar G, Shad B, Ariamajd E, Geranmayeh S. Effect of intensive non-surgical treatment on the level of serum inflammatory markers in advanced periodontitis. J Dent (Tehran) 2010;7:24–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonetti MS, D’Aiuto F, Nibali L, Donald A, Storry C, Parkar M, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:911–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mann KG. Biochemistry and physiology of blood coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:165–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montebugnoli L, Servidio D, Miaton RA, Prati C, Tricoci P, Melloni C, et al. Periodontal health improves systemic inflammatory and haemostatic status in subjects with coronary heart disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:188–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips DR. New directions in antithrombotic drug discovery: pharmacological uncoupling of arterial thrombosis from hemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;7 Abstract AS-TU-026. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hemker HC, Giesen P, AlDieri R, Regnault V, de Smed E, Wagenvoord R, et al. The calibrated automated thrombogram (CAT): A universal routine test for hyper- and hypocoagulability. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2002;32:249–53. doi: 10.1159/000073575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grassos C, Gourlis D, Papaspyropoulos A, Spyropoulos A, Kranidis A, Almagout P, et al. Association of severity of hypertension and periodontitis. J Hypertens. 2010;28:335–6. [Google Scholar]