Abstract

This case report presents a female patient whose chief complaint was of mobile and palatally drifted upper left central incisor which led to malalignment of upper anterior teeth. Orthodontic treatment of upper left central incisor was done with the help of ‘Z’ spring for the alignment of the upper anterior teeth. It was followed by splinting of upper anterior teeth to improve the stability and masticatory comfort. Regenerative periodontal surgery with Decalcified freeze dried bone allograft was done in relation to upper left central incisor.

Keywords: Bone graft, orthodontics, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Orthodontic treatment in adult patients who have advanced periodontal disease can be performed by a team of clinicians, using a multidisciplinary approach to reestablish dentition, both esthetically and functionally.[1]

Among the most notable clinical signs of advanced periodontitis is pathological tooth migration.[2] Pathological migration of anterior teeth is an esthetic and functional problem that may be associated with advanced periodontal disease. The destruction of tooth supporting structures is the most relevant factor associated with pathologic migration. Although some case reports have shown spontaneous repositioning of teeth following periodontal therapy alone, the treatment of severe cases of anterior spacing can be complex and time consuming and a multidisciplinary approach is often required including periodontal, orthodontic and restorative treatment.[3,4]

The number of periodontal pathogens in the anterior sites of malaligned teeth is much greater than that in the sites of aligned teeth.[5] The correction of the malaligned teeth can eliminate any harmful occlusal interference, which may offer a great opportunity for the development of a periodontal breakdown.[6] This data definitely supports the concept that orthodontic treatment can positively affect the periodontal health, prevent the development of periodontal diseases and offer a possible action to enhance the bone formation within the bony defects.[7,8,9] The purpose of this case report is to discuss how recent basic and clinical information may be used to improve the treatment planning, clinical management and retention of teeth in which pathological migration occurs owing to moderate to advanced periodontal destruction.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old Indian female patient came to the Department of Periodontology, Government Dental College and Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, with a chief complaint of loose and palatally drifted upper left central incisor, which led to malalignment of upper anterior teeth. Patient wanted to correct those teeth for restoring the esthetics [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pre-operative view

A comprehensive periodontal examination was completed including extraoral, intraoral and radiographic evaluations.

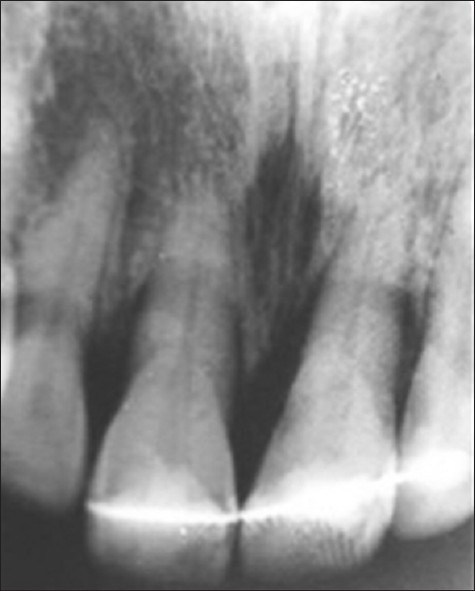

Thorough clinical examination revealed, the maxillary left central incisor was drifted palatally with Grade II mobility, with a 9 mm deep periodontal pocket. Radiographic evaluation revealed angular bony defect extending until middle-third of the root of maxillary left central incisor [Figure 2]. Intraoral clinical status assessment was made and the treatment was planned sequentially.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative radiograph

Initial periodontal treatment consisting of scaling and root planning was performed and patient was given oral hygiene instructions. An ideal diagnostic upper working cast was made. On that cast, “Z” spring with labial bow was fabricated [Figure 3]. The “Z” spring was made of 0.5 mm hard round stainless steel wire. The spring consisted of two coils of very small internal diameter. The spring was made perpendicular to the palatal surface of the tooth. It had a retentive arm of 10-12 mm length that was embedded in the acrylic. The “Z” spring was activated by opening both the helices by about 2-3 mm at a time. This removable appliance was modified to form a fitted labial bow, which was used as a retaining device during the treatment. Patient was advised to wear it for a period of at least 6 weeks [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

“z” spring with labial bow

Figure 4.

Placement of appliance in mouth

Post-orthodontic treatment, when maxillary left central incisor was realigned in the arch [Figure 5], it was splinted with the adjacent teeth to improve the stability and masticatory comfort [Figures 6 and 7]. Later, surgical intervention of left maxillary incisors was recommended to eradicate the deep infrabony pocket.

Figure 5.

Post-orthodontic treatment after 6 weeks

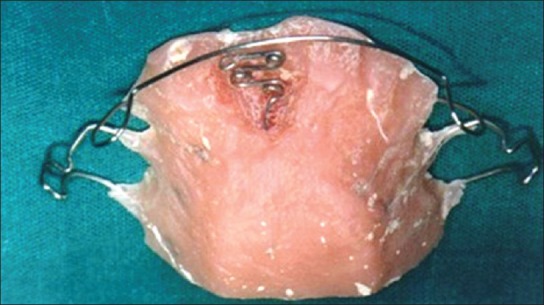

Figure 6.

Splinting

Figure 7.

Post-operative orthodontic treatment and splinting radiograph

After the full thickness, mucoperiosteal flap was reflected labially and palatally under local anesthesia, angular bony defect was found in relation to maxillary left central incisor [Figure 8]. The surgical site was grafted with decalcified freezed dried bone allograft [Figure 9]. The flaps were reapproximated and sutured. The sutures were removed after a week. Healing was uneventful. Patient was placed on a 3 month periodontal maintenance recall program [Figures 10 and 11].

Figure 8.

Reflection of Flap and debridement of defect

Figure 9.

Placement of bone graft

Figure 10.

Post-operative follow-up at 3 months

Figure 11.

Post-operative radiograph after 3 months

On post-treatment evaluation (after 8 years), realigned maxillary left central incisor was observed; thus, achieving an acceptable occlusion. Furthermore, there was a normal gingiva showing no evidence of bleeding on probing. Radiographic examination revealed significant fill of the infrabony defect [Figures 12 and 13].

Figure 12.

Follow-up after 8 years

Figure 13.

Post-operative radiograph after 8 years

Finally, the ortho-perio interdisciplinary approach resulted in the restoration of esthetics and function, thus improving self-confidence of the patient.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of periodontal therapy is to restore and maintain the health and integrity of the attachment apparatus of teeth. In adult patients, the loss of teeth or periodontal support can result in pathological migration involving either a single tooth or a group of teeth.[9]

Modern treatment and maintenance capabilities have made tremendous advances in allowing the severely damaged periodontally involved tooth to continue as a functioning member of the masticatory apparatus.[10] Wojcik et al. found that periodontally hopeless teeth that are retained do not significantly affect the proximal periodontium of adjacent teeth when treated with scaling and root planning, oral hygiene instructions, occlusal adjustment and periodontal surgery.[11]

In case of advanced periodontal disease with a pathological migration of anterior teeth, which may hamper esthetics, a combined periodontic-orthodontic therapy may be a reliable approach to solve both functional and esthetic problems.

The pathological migration of teeth is caused by unresolved inflammation and subsequent destruction of periodontal tissues, increasing periodontal tension and leading to direct extrusion of teeth where this is not prevented by opposing forces. Anterior teeth are therefore, especially prone to elongation and displacement since they are not protected by occlusal forces and have no anterior-posterior contacts, which are able to inhibit tooth migration.[12]

Many dentists are reluctant to refer adult patient for orthodontic treatment if they have suffered or are suffering from, obvious signs of periodontal disease such as chronic periodontitis. Periodontally compromised adult patients often present with drifting teeth leading to the development or worsening of a malocclusion. Many orthodontists are often reluctant to provide fixed appliance therapy. There is good evidence that if high quality periodontal intervention is carried out and patient is able to maintain adequate hygiene procedures to control the disease, even in the presence of alveolar bone loss, fixed appliance treatment can be carried out safely and satisfactorily.[13]

For orthodontic treatment in patient with periodontal disease, there should be appropriate control of existing inflammation and subsequent regular periodontal supportive care during orthodontic treatment. When considering the best time to begin orthodontic treatment in patient with moderate to advanced periodontitis, multiple factors should be considered. These include patient's compliance, motivation and plaque control levels, an effective periodontal treatment response, periodontal stability and reestablishment of a relatively stable occlusion. Patient should be followed for a period of up to 6 months after active periodontal treatment, for observation of resolution of inflammation and healing, prior to commencing orthodontic tooth movement.[14]

After proper periodontal therapy, orthodontic treatment can positively improve both alveolar bone and the soft periodontal tissues.[15]

In some patients, periodontal therapy may cause spontaneous correction of pathologic migration. Spontaneous repositioning in such cases can be attributed to the elimination of inflammation and repair of transseptal and other gingival fibers.[16] However, in the present case, there was no evidence of spontaneous repositioning of the teeth after periodontal treatment, probably because of the presence of severe bone loss around the involved incisor teeth.[17]

The present case report shows that patient with a pathological migration of maxillary left central incisor resulted in esthetic and functional problems. The malalignment was believed to be the result of pathological migration because previous crowding was not reported by patient. Since esthetic improvement was required in the maxillary anterior region, it was necessary to minimize the risk of secondary occlusal trauma that would result from excessive mobility of the teeth caused by extensive loss of the supporting bone.[18]

Periodontally compromised patients may have problems such as relapse during the retention stage and therefore these patients require a long period of retention. Permanent retention is often part of the total treatment plan for these patient, so that regeneration of bone can be completed without the risk of relapse and to eliminate secondary occlusal trauma, thereby improving patient comfort.[19,20]

CONCLUSION

In today's practice, conservation of the teeth is the main demand of patients with compromised periodontal support. They also seek esthetic and functional improvement. Advanced periodontal disease may result in pathologic migration and intraosseous defects. In such cases, combined orthdontic and periodontic treatment can greatly enhance periodontal health and dentofacial esthetics. Combined interdisciplinary treatment aim should include dental and facial esthetics, periodontal health, optimum functional occlusion, stable result and satisfaction of patients. Successful treatment and its long-term maintenance can only be achieved by close coordination between the periodontist and orthodontist.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ingber JS. Forced eruption. I. A method of treating isolated one and two wall infrabony osseous defects-rationale and case report. J Periodontol. 1974;45:199–206. doi: 10.1902/jop.1974.45.4.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bednar JR, Wise RJ. Interaction of periodontol and orthodontic treatment: Clinical approaches and evidence of success. Quintessence Int. 1998;1:149–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirelli JA, Cirelli CC, Holzhausen M, Martins LP, Brandão CH. Combined periodontal, orthodontic, and restorative treatment of pathologic migration of anterior teeth: A case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26:501–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deepa D, Mehta DS, Puri VK, Shetty S. Combined periodontic-orthodontic endodontic interdisciplinary approach in the treatment of periodontally compromised tooth. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:139–43. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.70837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindhe J, Svanberg G. Influence of trauma from occlusion on progression of experimental periodontitis in the beagle dog. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1974.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazit E, Lieberman M. The role of orthodontics as an adjunct to periodontal therapy. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim. 1978;27:5–12. 5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown IS. The effect of orthodontic therapy on certain types of periodontal defects. I. Clinical findings. J Periodontol. 1973;44:742–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.12.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diedrich P. Periodontal relevance of anterior crowding. J Orofac Orthop. 2000;61:69–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01300349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dannan A. An update on periodontic-orthodontic interrelationships. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:66–71. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.65445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson TG, Kornmanks KS, Melloning JT, Brunsvold MA. Treating aggressive forms of periodontal disease. In: Wilson TG, Kornman KS, editors. Fundamentals of Periodontics. Chicago: Quintessence Int; 1996. pp. 389–421. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojcik MS, DeVore CH, Beck FM, Horton JE. Retained “hopeless” teeth: Lack of effect periodontally-treated teeth have on the proximal periodontium of adjacent teeth 8-years later. J Periodontol. 1992;63:663–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Markenstam G. Intrusion of incisors in adult patients with marginal bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:232–41. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd RL, Murray P, Robertson PB. Effect of rotary electric toothbrush versus manual toothbrush on periodontal status during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:342–7. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tulloch JF. Adjunctive treatment for adults. In: Proffit WR, Fields HW, editors. Contemporary Orthodontics. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000. pp. 616–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu XF, Pan XG, Shu R. A preliminary study of combined periodontal-orthodontic approach for treating labial displacement of incisors in patients with periodontal diseases. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 2008;17:264–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaumet PE, Brunsvold MI, McMahan CA. Spontaneous repositioning of pathologically migrated teeth. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1177–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.10.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Re S, Corrente G, Abundo R, Cardaropoli D. The use of orthodontic intrusive movement to reduce infrabony pockets in adult periodontal patients: A case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda S, Maeda Y, Ono Y, Nakamura K, Matsui T. Interdisciplinary approach and orthodontic options for treatment of advanced periodontal disease and malocclusion: A case report. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:653–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalia S, Melsen B. Interdisciplinary approaches to adult orthodontic care. J Orthod. 2001;28:191–6. doi: 10.1093/ortho/28.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghezzi C, Masiero S, Silvestri M, Zanotti G, Rasperini G. Orthodontic treatment of periodontally involved teeth after tissue regeneration. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008;28:559–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]