Abstract

Context:

Evidence suggests that certain yoga practices are useful in the management of depression. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no study that deals with the formulation of a yoga module for the particular clinical features of depression.

Aim:

The main aim of our study was to develop a comprehensive yoga therapy module targeting specific clinical features of depression.

Settings and Design:

Specific yoga practices were matched for clinical features of depression based on a thorough literature review. A yoga program was developed, which consisted of Sukṣmavyayāma, (loosening exercises), äsanas (postures), relaxation techniques, Prāṇāyāma (breathing exercises) and chanting meditation to be taught in a 2 week period.

Materials and Methods:

A structured questionnaire was developed for validation from nine experienced yoga professionals. The final version of yoga therapy module was pilot-tested on seven patients (five females) with depression recruited from outpatient service of National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore.

Results:

The final yoga therapy module had those practices that received a score of three or more (moderately/very much/extremely useful) from all responders. Six out of nine (>65%) experts suggested Sūkśmavyāyāma should be included. Five out of nine experts opined that training with 10 sessions (over 2 weeks) is rather short. All experts opined that the module is easy to teach, learn and practice. At the pilot stage, the five patients who completed the module reported more than 80% satisfaction about the yoga practices and how the yoga was taught. Severity of depression substantially reduced at both 1 and 3 months follow-up.

Conclusion:

The developed comprehensive yoga therapy module was validated by experts in the field and was found to be feasible and useful in patients with depression.

Keywords: Antidepressant, depression, module, out-patients, yoga

INTRODUCTION

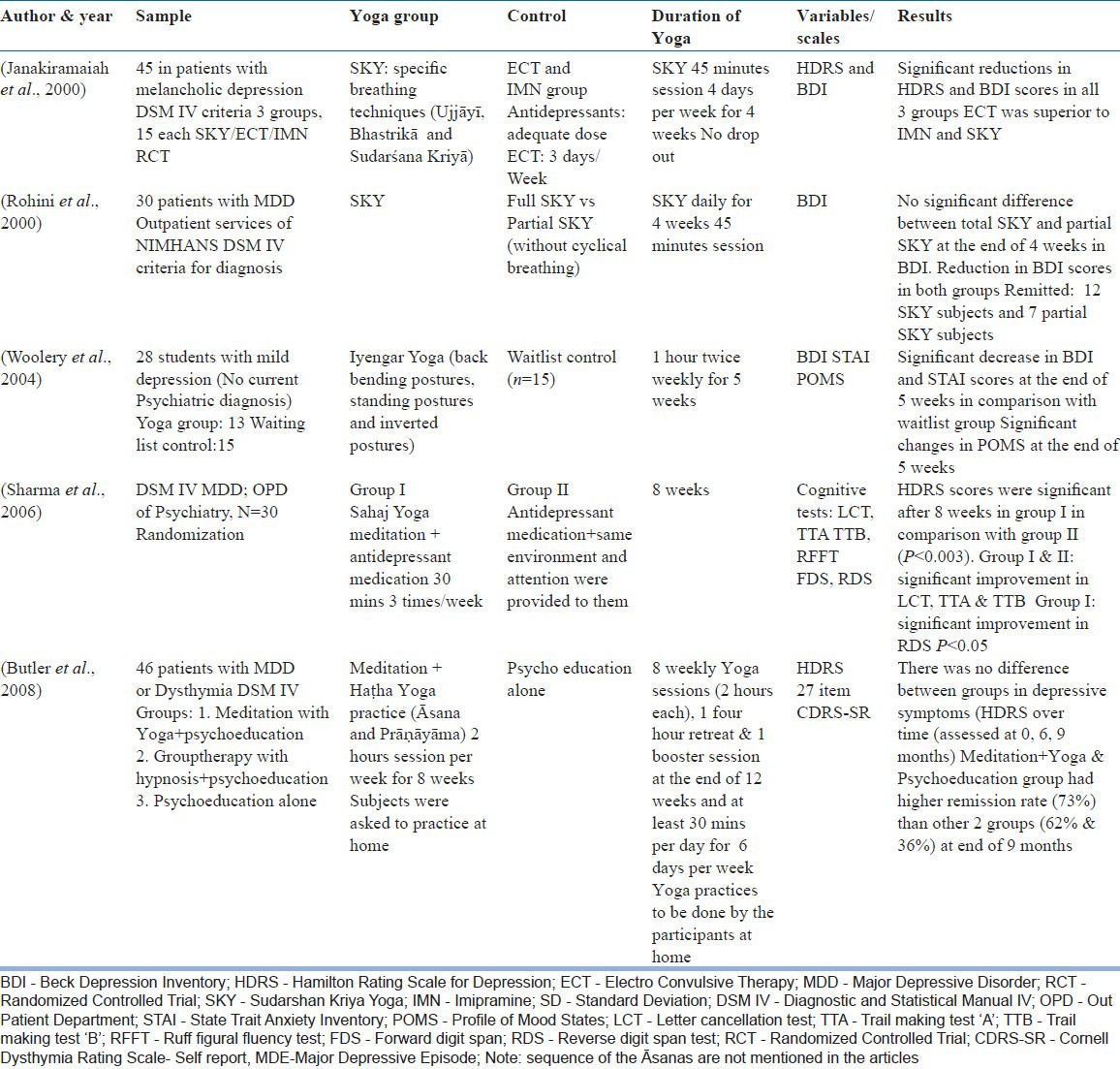

Earlier reports have suggested usefulness of yoga in the treatment of depression.[1,2] Practices used in these reports have been different. Yogāsanas, breathing exercises, meditation and relaxation techniques have been used individually or in different combinations.[3,4,5,6] Previous controlled studies on yoga in depression are detailed in Table 1. The rationale for choosing any of these methods merits attention. The traditional texts do not refer to yoga practices specifically aimed at helping the syndrome of depression.

Table 1.

Previous Controlled studies of Yoga and depression

Development of yoga modules for use in elderly subjects,[7] caregivers of persons with disease or disability,[8] and caregivers of patients with schizophrenia[9] have been described in the literature.

We are unaware of development of a yoga module specifically for therapy of patients with depressive disorder. In this report, we describe the process of developing a module for depressive disorder that was pilot-tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

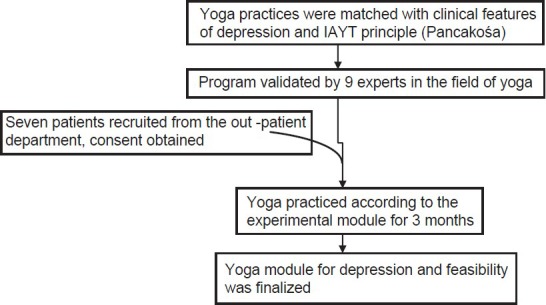

Yoga therapy module development [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Depicts the steps in the development of the yoga module

The yoga module was developed by the researcher, with 5 years’ experience in yoga therapy. Specific yoga practices were selected by matching the clinical features of depression.[10] Classical yoga texts such as Hatha Yoga Pradeepika,[11] Gheraṇda samhitā[12] and Patañjali yoga sūtrās[13,14] and also contemporary yoga texts such as Yogāsanā Vijïäna;[15] Integrated approach of yoga therapy for positive health;[16] Prāṇāyāma - The arts and science;[17] Yoga Darśana;[18] Sūryanamaskara (sun solutation);[19] light on yoga[20] and yoga therapy series-yogic management of diseases[21] formed the sources of information on yoga. These were reviewed to understand the yoga practices that would lessen directly or indirectly the clinical features of depression. The review showed that āsanas mentioned in Table 1 are useful directly or indirectly to address different clinical features of depression. Yogic counseling was also included by taking references from yoga texts such as Bhagavad-gītā, Patañjali yoga sūtrās[13,14] and Yogavaśista. A power point of slides used for counseling was developed. Yoga practices that helped against Tāmasik Guëa were included as Tāmasik predominance has been known to be associated with symptoms of depression.[22] Besides this Guëas (personality predominance) of patients, scientific evidence about effects of specific practices (e.g., backward bending postures, fast breathing exercises) were also considered.[3,5,23]

Validation

The research protocol was approved by the institute's ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from the yoga experts who validated this module. Nine experts were contacted for the purpose of validation: Five experts had PhD in yoga, one had a graduate degree in yoga and Naturopathy, one physician (MD) had been practicing yoga as therapy for over three decades, one medical graduate (MBBS) had a formal training in yoga and one who headed the yoga therapy department was formally trained in yoga. The average number of years of clinical experience with yoga was close to 20 years (range: 12-36 years). Their average age was 45 years (range: 35-66 years). Experts selected were essentially a convenience sample. The experts were known to authors and thus were expected to return the forms after completing them promptly. They were all using yoga for therapeutic purposes in different illnesses. However, this (yoga therapy) was not the primary profession in some of them.

Experts were requested to rate the usefulness of the practices listed on a 5 point scale ([1] not at all useful, [2] a little useful, [3] moderately useful, [4] very much useful [5] extremely useful). Four additional questions were posed.

Do you have any comment/alternative to those practices that you have rated as 1 or 2?

Should Sukṣmavyayāma (loosening exercises) be used as part of the module?

Is the duration of training (10 days over 2 weeks) sufficient to learn and practice these at home for 3 months?

How easy/suitable are these procedures for men and women between 18 and 55 years?

In addition, they were requested to provide any other comments or suggestions. They also received five case vignettes of patients with major depressive disorder to indicate that yoga module was aimed at helping patients of such nature.

Eventually, the researcher made changes in the module as per the suggestions/comments/rating by the professionals. A final yoga therapy module for depression was developed by incorporating the comments of the nine experts who responded. The final script included the list of yoga practices technique along with pictures and a brief note on yogic counseling. The handouts of this were developed for distribution to the participants.

Pilot study

This too was approved by the institute's ethics committee. All participants signed an informed consent form.

The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of yoga therapy module in out-patients with depression.

Seven out-patients (five females) who had a diagnosis of major depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders-IV[24] consented for the study. Their diagnosis was confirmed by qualified psychiatrist who also excluded mental retardation and co-morbid substance use disorders (except nicotine). No patient had history suggesting mania or psychosis in the past. None had history of epilepsy or cerebrovascular accidents. They had no contraindications for practicing yoga (recent fracture, major surgery, de-compensated cardiac functions etc.). Patients were aged between 18 and 55 years. They had scored 11 or more on Hamilton depression rating scale (HDRS).[25]

Five of them completed 10 days training as well as practice at home for 3 months. HDRS was administered at baseline, end of 1 month and 3 months. At this point, they completed the feedback form that included the degree of improvement from depression and the degree of satisfaction of learning the module on a visual analogue scale of 100 mm. Paired sample t-test was used to compare HDRS scores at baseline, 1 month and 3 months of yoga practice.

RESULTS

Development and validation and final yoga module

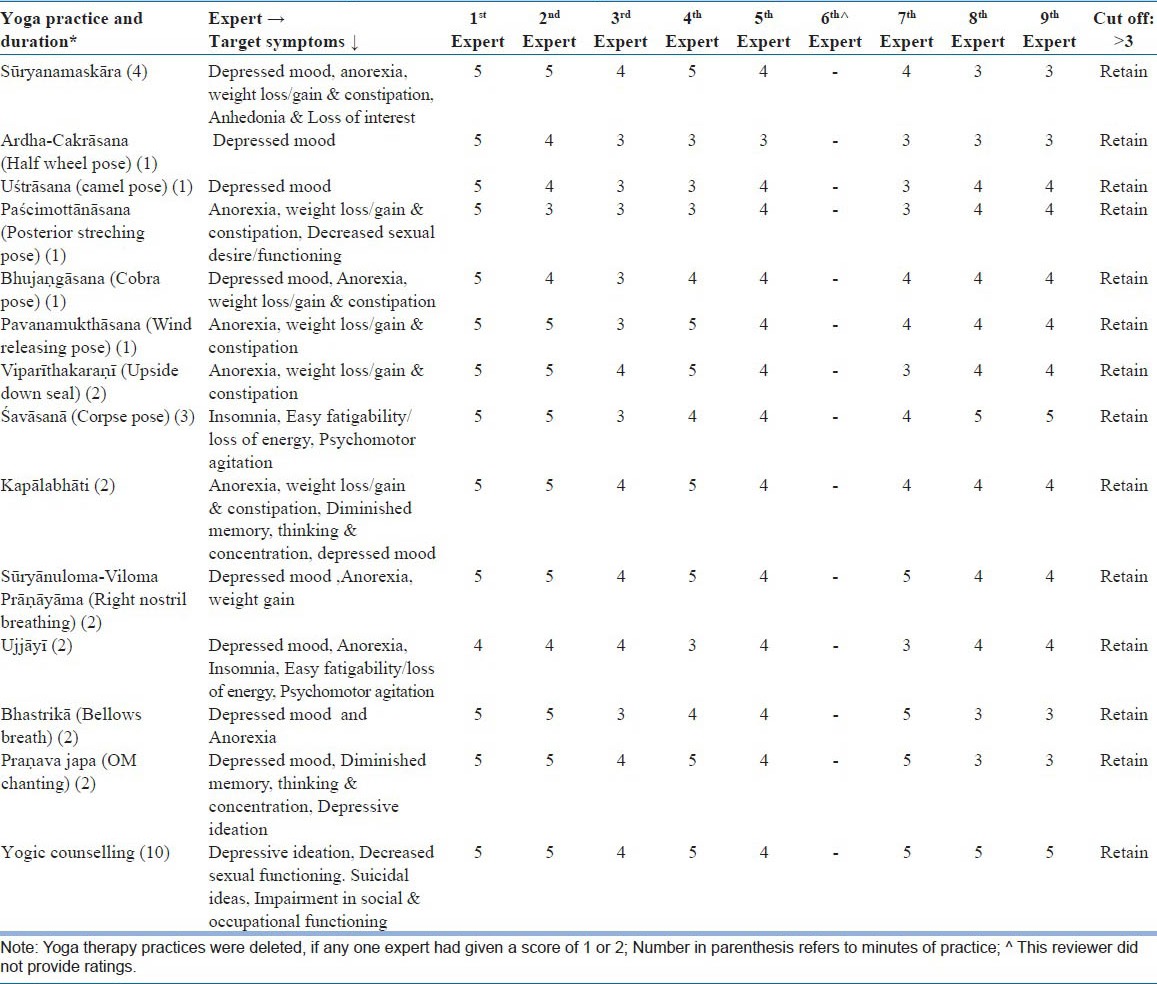

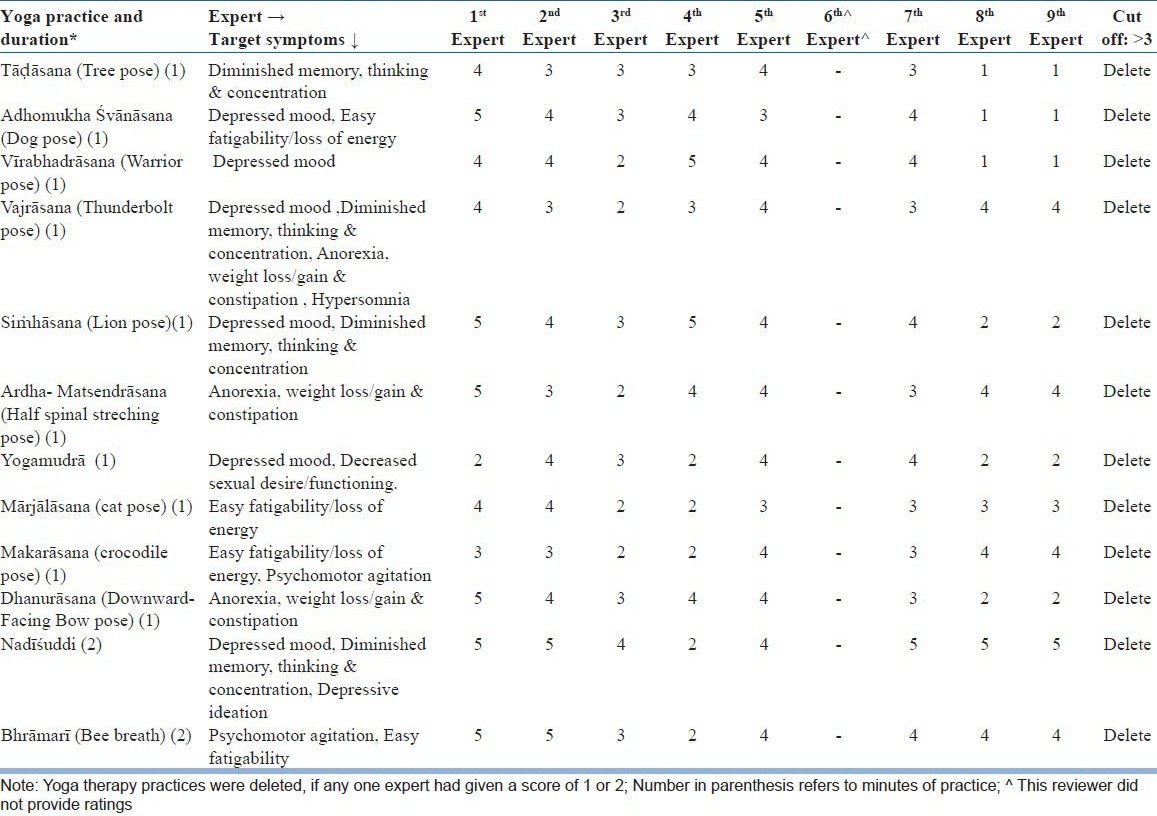

Table 2a shows the final module and the ratings provided by the experts to the different components of the module. Table 2b shows the deleted practices based on the recommendations by the experts.

Table 2a.

shows the retained practices of the Yoga module, their target symptoms and ratings provided by the experts to the different components of the Yoga module

Table 2b.

Shows the Yoga practices deleted from the final module and their ratings by the experts

All the nine experts provided written response sheets. However, one of them did not provide ratings for the usefulness of each yoga practices. The final yoga module retained those practices that scored three or above by all who completed this rating. Six of the eight experts (75%)recommended the addition of Sukṣmavyayāma. This was hence included. The order of the practices in this was different across sessions to avoid monotony.

We modified the module based on two aspects: (a) components, which were given ratings of two or less by any of the experts, were deleted and (b) suggestions given by the experts were reviewed and incorporated.

Based on ratings provided, 12 practices were deleted and the others were retained. All experts opined that the module is easy to teach, learn and practice. Five of the nine opined that 2 weeks training was short and suggested to increase to 3 weeks.

As we felt that patients would find it hard to practice under the supervision for 3 weeks continuously, we retained 2 weeks of supervised training, but added two more sessions in each of the next 2 weeks and also one session at the start of next 2 months. Two weeks was chosen based on earlier experiences on outpatient subjects.[26] As compensation, we added three more sessions (one each at the end of week 3 and 4 and one at the end of week 8). We also provided one at the end of week 12 when the patients were assessed. The suggestion that we could have tested a longer training module will be considered if the initial results are less satisfactory. However, it is to be noted that yoga practices on the rest of the days were monitored by a family member. Based on the comments on the sequence of yoga practices given by four experts following order was finalized. i.e., one fast repetitive practice followed by the slow movement and then to maintaining a final posture. This was performed to avoid boredom, which is usually prevalent in patients with depression. E.g., fast forward-backward bend for 10 times, then repeat Pādahastāsanā - Ardhacakrāsana with slow breathing 5 times, then maintain in Ardhacakrāsanā (Half wheel pose) for 30 s. Similarly, fast breathing followed by slow breathing and one slow chanting will help them to maintain their awareness, thus order of the sequence was revised based on the experts opinion. Further Setubandhāsana (bridge pose) and breathing exercises were included as per the expert's suggestion to include back bending postures and breathing exercises. Furthermore, additional comments of two experts were included. Advise on consuming Satvik foods was suggested by them. Given the practical difficulties in supervising the food in OP patients this aspect was deliberately retained as an information and suggestion instead of prescription. This element will be used to fortify the yoga module if proved to be less potent in our studies. Although it was difficult to advice consuming only Sātvik foods, participants were educated about the importance and source of these foods during yogic counseling.

Pilot study

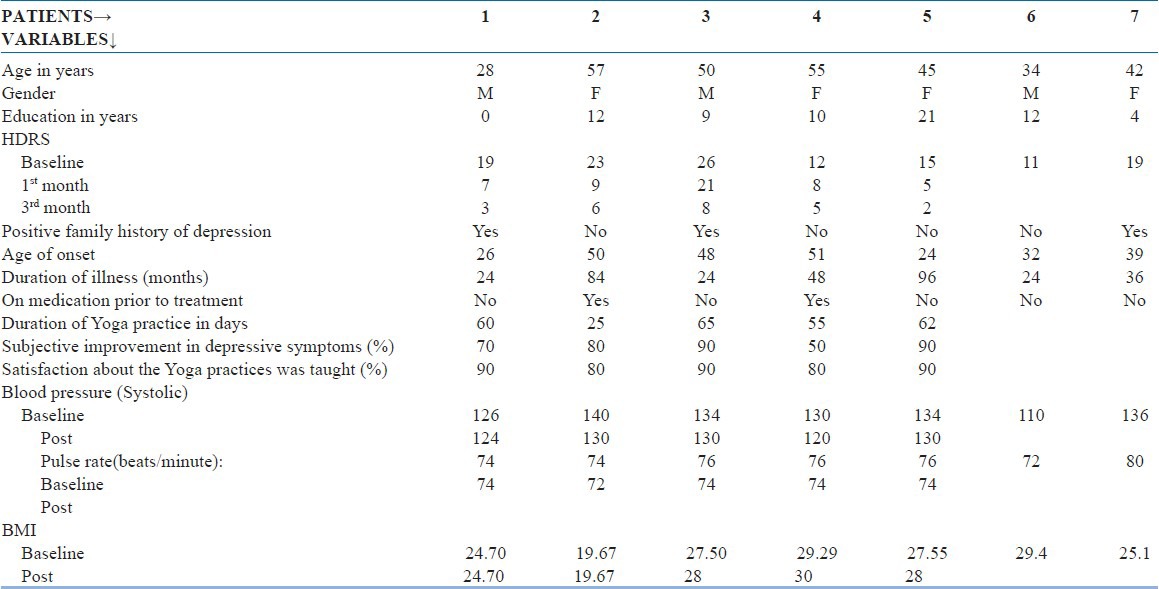

Five patients completed the pilot study [Table 3]. All the completed patients had a drop in the depression scores. They reported over 80% or more satisfaction about Yoga practices and substantial improvement in their depressive symptoms [Table 3].

Table 3.

Socio-demographic and clinical details of patients with depression (n=7). Patients # 6 and 7 dropped out

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a yoga module for treating depression by choosing specific yoga practices from the traditional literature on yoga to target specific symptoms of depression. The module was validated by experts in yoga therapy and was modified according to their suggestions. We retained only those practices, which were rated by all experts as useful (score of three or more). We also ordered the yoga practices in the module as suggested by experts. The training sessions were increased as “booster” sessions at spaced intervals after the first two weeks. All experts opined that these practices should be easy for patients of depression. We also included some loosening exercises as majority suggested so.

The pilot study found that the yoga module was well received by patients of depression. They all reported improvement. They were also satisfied with the module. The measures of depression yielded lowering of scores indicative of therapeutic benefit. No spontaneous reportage of side-effects occurred after yoga.

To our knowledge, this is the first time a specific yoga module has been developed with components addressing specific symptoms of depression. This matching of yoga practices with symptoms of depression was performed after reviewing traditional literature[3,11,12,15,16,18,19,20,21,27,28] This is in contrast to the modules used by previous researchers. Initially, the plan was to train the practices over a 2-week period in ten sessions and let the patient practice them at home on a daily basis for 3 months. Nearly, all experts opined that the duration of training was short. Accordingly, we changed this by adding two sessions at weekly intervals in the next 2 weeks and two more sessions at monthly intervals in next 2 months. On all other days, the patient is advised to follow the practices at home. Having to come daily for longer periods to yoga center for therapy/training has been recognized as an important barrier[26] for patients with psychiatric disorders. Therefore, our approach of spacing the latter sessions appears pragmatic. The length of intervention varied between 1 and 3 h in earlier yoga studies. A recent study included 8 weekly group sessions of 2 h each, one 4-h retreat and one booster session in week 12.[29] Another study had a duration of 30 min for 3 times a week for an 8 week period.[6] Woolery et al. had duration of 1 h twice weekly for 5 weeks.[30] Rohini et al. had duration of 4 weeks daily[31] and Janakiramaiah et al. had duration of 4 days/week for 4 weeks.[3] All these studies reported positive findings in reducing depression scores in patients with depression. Hence, our study duration is in similarity with the majority of the previous studies.

In the pilot study, the patients who completed the 3 months therapy as scheduled in this module reported satisfaction. Not only were their self-ratings indicative of reduction in depressive symptoms; clinical ratings on a scale too were corroboratory. This is in keeping with the known antidepressant effects of yoga.[3,5,6,32] However, this is not an evidence for efficacy of this yoga module in depression. No spontaneous reporting of side-effects from these five subjects reinforces a case for testing this yoga a module for therapy in depression.

The efficacy of this module needs to be tested in comparison with existing antidepressant therapies and where possible, against a placebo despite the limitations of finding a suitable placebo yoga.[33] Biological correlates of the effects of this yoga module in depression too deserve attention.

In summary, a yoga module for use as treatment in depression was designed based on traditional texts and was validated with the help of experts. The final module that was developed was found to be acceptable by patients in a pilot run. The module remains to be tested in formal clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr. R. Nagarathna, Dean, Life Sciences, Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandana Samsthana, Bangalore for her support, encouragement and guidance.

We thank Mr. Sushrutha and Mr. Bhagath of Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana for their help with transliteration.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The research was done under the Advanced Centre for Yoga - Mental Health and Neurosciences, a collaborative centre of NIMHANS and the Morarji Desai Institute of Yoga, New Delhi

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iyengar BK. 2nd ed. Great Britain: Dorling Kindersley Limited; 2008. Yoga the Path to Holistic Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. 1st ed. Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2001. Yoga practices for anxiety and depression. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Naga Venkatesha Murthy PJ, Harish MG, Subbakrishna DK, Vedamurthachar A. Antidepressant efficacy of sudarshan kriya yoga (SKY) in melancholia: A randomized comparison with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khumar SS, Kaur P, Kaur S. Effectiveness of shavasana on depression among university students. Indian J Clin Psychol. 1993;20:82–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro D, Cline K. Mood changes associated with iyengar yoga practices: A pilot study. Int J Yoga Therap. 2004;14:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma VK, Das S, Mondal S, Goswami U, Gandhi A. Effect of sahaj yoga on neuro-cognitive functions in patients suffering from major depression. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;50:375–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen KM, Tseng WS, Ting LF, Huang GF. Development and evaluation of a yoga exercise programme for older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:432–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Puymbroeck M, Payne LL, Hsieh PC. A phase I feasibility study of yoga on the physical health and coping of informal caregivers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:519–29. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagannathan A, Hamza A, Thirthalli J, Nagendra H, Nagarathna R, Gangadhar BN. Development and feasibility of need-based yoga program for family caregivers of in-patients with schizophrenia in India. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:42–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.91711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svatmarama . 4th ed. Adyar (Madras, India): Adyar Library and Research Centre; 1994. Hatha Yoga Pradipika of Svatmarama. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Digambarji S, Gharote ML. 1st ed. Lonavala (India): Kaivalyadhama S.M.Y.M Samiti; 1978. Gheranda Samhita. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyengar BK. London: Harper Collins Publishers; 1993. Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadhakas . 4th ed. Santacruz, Bombay, India: The Yoga Institute; 2006. Patanjali Yoga Sutras. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahmachari D. New Delhi, India: Dhirendra Yoga Publications; 1983. Yogasana Vignana. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R. Bangalore, India: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2008. Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy for Positive Health. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagendra HR. Bangalore, India: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2007. Pranayama-The Art and Science. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraswati SS. Munger, Bihar, India: Yoga Publications Trust; 2005. Yoga Darshana. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraswati SS. Munger, Bihar, India: Yoga Publications Trust; 2004. Suryanamaskara. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyengar BK. London: Harper Collins Publishers; 1993. Light on Yoga. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acharya I, Basavaraddi IV. New Delhi (India): Morarji Desai National Institute of Yoga; 2007. Yoga therapy series-Yogic management of diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dasa DG. Ardennes, Belgium: Bhaktivedanta College; 1999. The vedic personality inventory-An analysis of gunas. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro D, Cook IA, Davydov DM, Ottaviani C, Leuchter AF, Abrams M. Yoga as a complementary treatment of depression: Effects of traits and moods on treatment outcome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baspure S, Jagannathan A, Kumar S, Varambally S, Thirthalli J, Venkatasubramanain G, et al. Barriers to yoga therapy as an add-on treatment for schizophrenia in India. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:70–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.91718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brahmachari D. New Delhi, India: Dhirendra Yoga Publications; 1983. Sukshma Vyayama. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Telles S, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Autonomic changes during “OM” meditation. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;39:418–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler LD, Waelde LC, Hastings TA, Chen XH, Symons B, Marshall J, et al. Meditation with yoga, group therapy with hypnosis, and psychoeducation for long-term depressed mood: A randomized pilot trial. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:806–20. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolery A, Myers H, Sternlieb B, Zeltzer L. A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:60–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohini SS, Pandey RS, Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Vedamurthachar A. A comparative study of full and partial sudarshan kriya yoga (SKY) in major depressive disrder. NIMHANS J. 2000;18:53–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: The research evidence. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gangadhar BN, Varambally S. Yoga as therapy in psychiatric disorders: Past, present and future. Biofeedback. 2011;39:60–3. [Google Scholar]