Abstract

Context:

The efficacy of yoga as an intervention for in-patients with psychosis is as yet unknown; although, previous studies have shown efficacy in stabilized out-patients with schizophrenia.

Aim:

This study aimed to compare the effect of add-on yoga therapy or physical exercise along with standard pharmacotherapy in the treatment of in-patients with psychosis.

Settings and Design:

This study was performed in an in-patient setting using a randomized controlled single blind design.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 88 consenting in-patients with psychosis were randomized into yoga therapy group (n=44) and physical exercise group (n=44). Sixty patients completed the study period of 1½ months. Patients who completed in the yoga group (n=35) and in the exercise group (n=25) were similar on the demographic profile, illness parameters and psychopathology scores at baseline.

Results:

The two treatment groups were not different on the clinical syndrome scores at the end of 2 weeks. At the end of 6 weeks, patients in the yoga group however had lower mean scores on Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGIS), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (total and general psychopathology subscale) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (P<0.05). Repeated measure analysis of variance detected an advantage for yoga over exercise in reducing the clinical CGIS and HDRS scores.

Conclusion:

Adding yoga intervention to standard pharmacological treatment is feasible and may be beneficial even in the early and acute stage of psychosis.

Keywords: In-patients, psychosis, schizophrenia, yoga

INTRODUCTION

In-patient care in the acute phase of functional psychosis (including schizophrenia) is often found necessary. First and second generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA) have a profound role in reducing symptoms as well as disability.[1] Following acute care too, a substantial number of patients remain modestly symptomatic, needing other inputs. Yoga is one among these complementary therapies that has received attention in recent years.[2,3] Randomized trials in medication-stabilized patients have demonstrated the efficacy of yoga in treating schizophrenia,[4,5,6] particularly negative symptoms (Varambally, personal communication). Yoga also benefits social cognition in schizophrenia.[7] However, the efficacy of yoga as a complementary intervention in acutely ill-patients during in-patient care has not been examined. One of the reasons may be apprehensions about the feasibility of teaching yoga practices to patients in the acute stage of psychosis. On the positive side, patients being admitted in the hospital might overcome a potential barrier for seeking yoga therapy.[8] In this study, relative benefits of either yoga or exercises given concurrently with the antipsychotic treatment in newly admitted patients of functional non-affective psychosis were studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Settings and design

The study was conducted in the wards of a large psychiatric institute. The Institute's Ethics Committee approved this study. Newly admitted (within past 1 week) patients with a diagnosis of functional non-affective psychosis formed the study population. If their status permitted participating in yoga/exercise, they were invited to participate in a randomized trial. The treating consultant psychiatrist made a clinical Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition diagnosis.[9] This was later confirmed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview by the first author.[10] All except five received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The major subgroup was paranoid schizophrenia (46.6%). The rest of the patients were diagnosed to have other subtypes of schizophrenia (41.9%) and unspecified psychosis (11.5%).

Patients received antipsychotic medication at therapeutic doses with anti-parkinsonian drugs as needed. The drug management was under the control of their treating psychiatrist, unrelated to this yoga trial. In the 2 weeks of in-patient study, the doses were changed by the treating psychiatrist as needed and therefore only the nature of drugs was recorded (FGA or SGA).

Adult psychiatry units and nurses referred patients to the research team. The first author (MRB) screened the referred patients using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. He informed the patients about their suitability for this study (i.e., their clinical state permitted them to perform yoga/exercise) and sought their consent to take part in the study. They were also explained that these procedures (yoga/exercise) had been earlier used in out-patients with similar illness and also that the procedures did not cause any adverse effect in them. The patients’ competence to comprehend the information and consent was assessed clinically (no scale was used to assess competence). In rare circumstances, when the researcher doubted their competence, consent was also sought from the relative who stayed with patients or available during the hospitalization. Patients and relatives were explained about the study through an information brochure as well as in-person interview; they were counseled about their right and freedom to refuse to take part in the study as well as to withdraw their consent at any stage of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient/family members who were willing to partake in the study.

A randomization table was generated for 90 patients to have equal representation of yoga or exercise as an add-on/complementary treatment. However, the recruitment had to be stopped after 88 patients when 44 patients each had been randomized into yoga and exercise groups.

These consenting patients (n=88) were randomized equally to receive yoga or exercise therapy sessions daily over 2 weeks in the wards (at least 10 sessions). The procedures for these two interventions were adopted from an earlier study.[4] The modules for yoga and exercise used in this study are available with the authors on request. A formally trained yoga therapist provided both these sessions for corresponding patients in batches not exceeding five. Each session lasted 1 h. After 2 weeks, patients were advised to practice the same for the next 4 weeks. The family members, who were observing their training during their inpatient stay, were requested to monitor their performance at home after discharge.

Patients’ demographic data was recorded on a pro forma. They included sex of the patient, age, age at the first onset of psychosis symptoms, total duration of illness from this point, marital status, education (college or lower) and current medication (FGA or SGA). The severity of clinical state was measured on Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),[11] Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)[12] and Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGIS).[13] Assessment was performed at the time of starting yoga/exercise as well as 2 and 6 weeks thereafter. At these 3 time points, the extrapyramidal (Parkinsonian) side-effects too were measured using Simpson Angus Scale (SAS).[14]

Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between the treatment groups using Chi-square and independent sample t-tests. Differences in clinical symptoms scores were compared between the groups at 2 weeks and 6 weeks using independent sample t-test. Change in symptom scores over the sessions and between the two groups were examined using two-way repeated measure analysis of variance (RMANOVA). Alpha was fixed at 5%.

The primary outcome was change in CGIS and total PANSS scores. Secondary outcomes included changes in the subscale scores of PANSS (positive, negative and general), total HDRS and SAS scores.

RESULTS

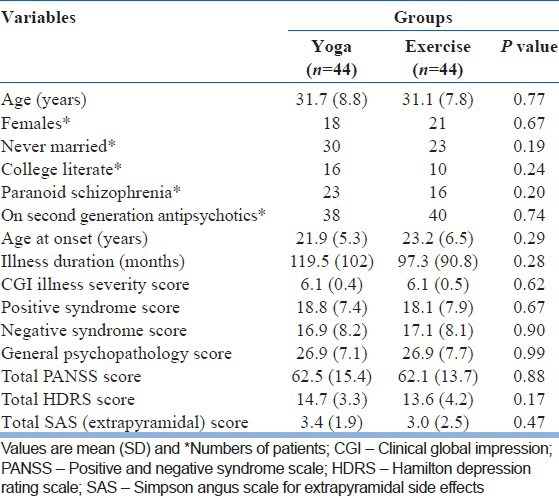

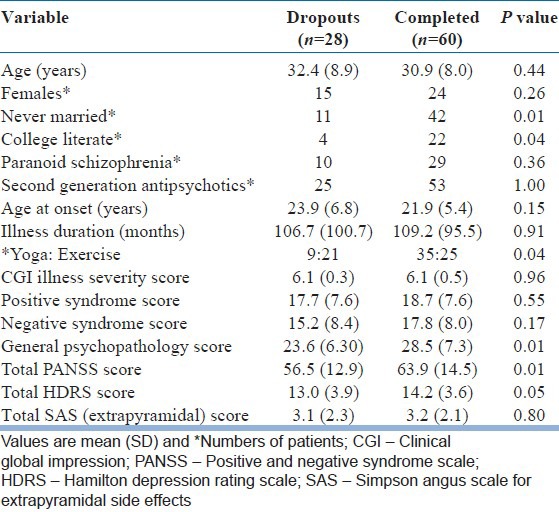

The two groups of patients who were randomized were comparable on all the parameters measured [Table 1]. Among the 88 patients, 82 completed the 2-week intervention successfully and were assessed at that time point. During follow-up at 6th week, more patients dropped out (n=28) and only 60 were available for third assessment (completed sample). The proportions of patients dropping out at the 2nd week were not significantly different across groups (exercise=5; yoga=1). At the 6th week, more patients in the exercise group had dropped out (19 vs. 9; P<0.04). Patients who dropped out were comparable to the completed sample on most parameters except a few; fewer patients who were married and college educated dropped out. Patients who dropped out had also scored lower on PANSS general psychopathology, PANSS total and HDRS scores at baseline [Table 2]. In the sample that completed all three assessments (n=60), the two groups (yoga and exercise) were comparable on all demographic and clinical variables.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between groups

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between dropouts and the completed group

Follow-up assessments

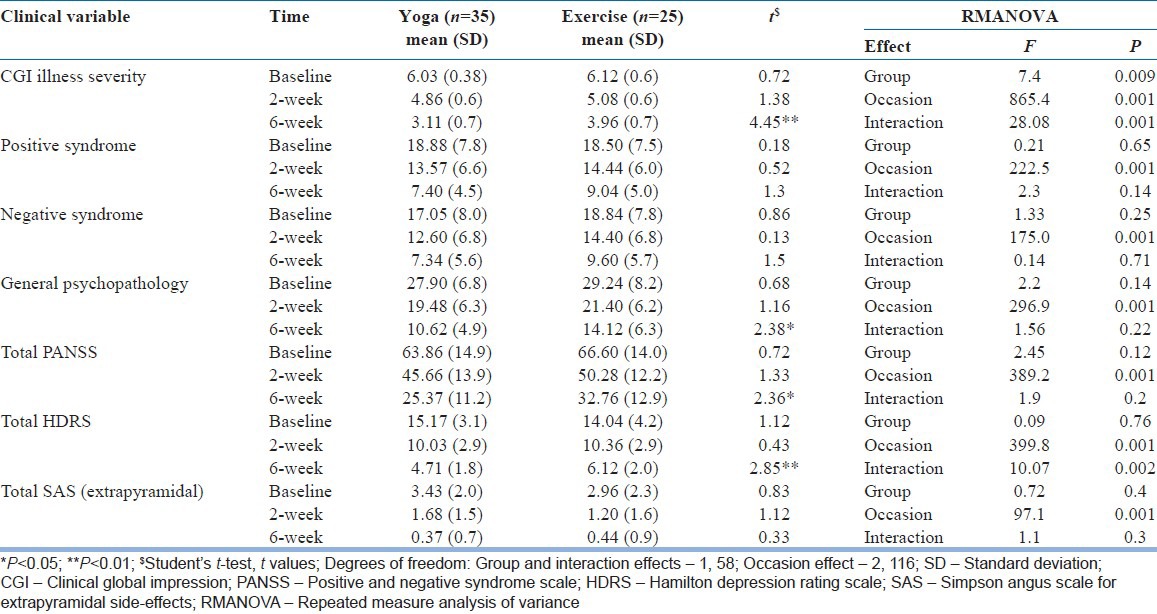

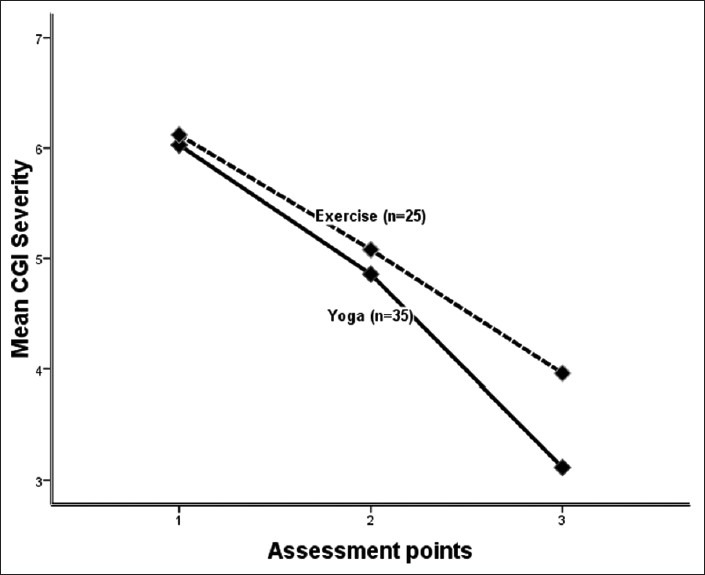

The two treatment groups were not different on the clinical syndrome scores at the end of 2 weeks. At the end of 6 weeks however, patients in the yoga group had lower mean scores on CGIS, HDRS, total PANSS and PANSS general psychopathology subscore [Table 3]. RMANOVA detected an advantage for yoga over exercise in reducing the CGIS scores and HDRS scores; though, the scores dropped in both treatment groups [Table 3 and Figure 1].

Table 3.

Outcome on clinical scales at different assessment points among the completers in yoga and exercise groups

Figure 1.

Among those available at all assessment points (1=baseline, 2=2 weeks, 3=6 weeks) the Clinical Global Impression Severity scores significantly fell over the treatment (occasion effect; F=7.7, df=1, 56, P<0.005). Scores were lower in the yoga group (group effect; F=7.7, df=1, 56, P<0.005) and the difference was widest in favor of yoga at the last assessment (interaction effect; F=7.7, df=1, 56, P<0.005)

DISCUSSION

This study examined the relative merits, if any, of yoga and exercise in newly admitted in patients with functional, non-affective psychosis, most of whom had a diagnosis of Schizophrenia. Among patients who completed 6 weeks follow-up, the yoga group obtained a significant advantage in reduction of illness severity.

However, nearly a third of the sample (n=28 of 88) were not available for the study until the end. In addition, those who remained in the study differed from those who dropped out on variables such as marital status, education and baseline illness severity [Table 2]. This suggests that the sample was not necessarily representative of the in-patients who were newly admitted with such diagnosis. This calls for more inputs into the study to bring back a larger number of them to follow-up sessions. In this study, it was not possible to prescribe several constraints as patients were from different wards and from different clinical teams. Given these limitations, the findings from this study must be viewed with caution. In the completed sample, the variables were comparable across the yoga and exercise groups, suggesting that the dropout (though higher in the exercise group) did not influence the group characteristics. The diagnostic status, illness duration, as well as drug status, was similar in the two groups. It is well-known that in the acute phase of treatment in psychosis, these play a major role. Therefore, the differences detected at the end of the study may truly be a result of the two additional experimental therapies that were compared.

The setting of the study was a large mental hospital. Nurses encourage some form of physical activity, though unstructured, for patients who can participate. Games, exercises and some chanting in varied combination are given in the wards to those patients who are able to participate. This ward session happens between 8 and 9 am. The patients of this study were not instructed to necessarily refrain from this session. It is likely that the yoga/exercise session of this study was in addition to the morning's nurses’ inputs. No record of this however was maintained. We had also not planned a “placebo” group, which precludes a comment on the efficacy of such structured physical activity as a complementary therapy. Wait-listed patients receiving treatments as usual could have been the best, yet limited, option as a control.[15] However, these patients too would receive some physical activity inputs in this ward hence narrowing differences of such intervention in this study. Resources limited efficient monitoring of the practices at home. At 6th week follow-up many patients came alone or with different caregivers/kin and hence the report of practice at home was not reliably obtained.

Severity of symptoms dropped in both groups from baseline through 2nd to 6th week in both groups. A large proportion of the improvement is expected to be a contribution by the potent drug treatments (mostly the SGA's). We have only recorded the class of the drug, but not its dose. This is a limitation partly because different drugs were used by different treating psychiatrists. We assume that randomization would have protected the study from this potential confound. Yet, a small difference was detected between yoga and exercise groups. At the end of the study, patients who have received yoga had lower scores on PANSS, HDRS as well as CGIS [Table 3]. The effect sizes of these differences were however only modest. In the multivariate model (RMANOVA), significant group and interaction effects in favor of yoga group were detected only on CGIS ratings and depression ratings. The rater on this scale was uninvolved in the treatment and therefore blind to group status. Furthermore, patients received the experimental therapy sessions in a separate location and hence the rest of the ward staff too was expected to be unaware of the treatment groups. Yoga and exercise intervention were both provided by the same therapist. The therapist could have inadvertently emphasized the need for regular practice and follow-up thereof in yoga intervention group. As a result, better adherence and/or follow-up could have occurred in the yoga group. However, different therapists for these two interventions could invite other methodological concerns.[15] Furthermore, lack of a record of practice at home is a limiting factor in this study.

Given the known antidepressant effects of yoga,[16] it is not unexpected to have lower HDRS scores in this group at the end of the study. The narrow differences between the two interventions are expected as exercise is also known to help mood states and perhaps offer other unknown benefits of well-being to individuals.[17] In this regard, absence of a group that did not receive any other similar inputs during hospital stay becomes important. Both interventions in this study could have proved beneficial to patients, though yoga proved statistically superior in this data.

Patients did not spontaneously report any adverse event that was clinically regarded as related to these interventions. Future studies must have a provision to directly elicit the same to confirm the absence of side-effects with such interventions. Multicenter, larger studies with a control sample may definitively test the efficacy of such interventions. Until then, we may only cautiously encourage the use of yoga as a complementary intervention where possible, in centers offering inpatient treatment to patients with psychosis. There is also a need to examine if such benefit extends to patients with other diagnostic conditions receiving treatment in the wards.

In summary, a structured yoga or exercise program for 2 weeks is feasible during acute in-patient care for patients with functional non-organic psychosis. Short term outcome favors yoga over exercise, though with only a modest effect size.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable inputs from Dr. D K Subbakrishna, Professor and Head, Department of Biostatistics, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences.

We thank Mr. Sushrutha and Mr. Bhagath of Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana for their help with transliteration.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The research was done under the Advanced Centre for Yoga - Mental Health and Neurosciences, a collaborative centre of NIMHANS and the Morarji Desai Institute of Yoga, New Delhi

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thirthalli J, Venkatesh BK, Naveen MN, Venkatasubramanian G, Arunachala U, Kishore Kumar KV, et al. Do antipsychotics limit disability in schizophrenia? A naturalistic comparative study in the community. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:37–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Knapen J, Wampers M, Demunter H, Deckx S, et al. State anxiety, psychological stress and positive well-being responses to yoga and aerobic exercise in people with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:684–9. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.509458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Yoga: A spiritual practice with therapeutic value in psychiatry. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5:186–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varambally S, Gangadhar BN, Thirthalli J, Jagannathan A, Kumar S, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia: Randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:227–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visceglia E, Lewis S. Yoga therapy as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia: A randomized, controlled pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:601–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behere RV, Arasappa R, Jagannathan A, Varambally S, Venkatasubramanian G, Thirthalli J, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on facial emotion recognition deficits, symptoms and functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:147–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baspure S, Jagannathan A, Kumar S, Varambally S, Thirthalli J, Venkatasubramanain G, et al. Barriers to yoga therapy as an add-on treatment for schizophrenia in India. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:70–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.91718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guy W. Rockville (MD): National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. ECDEU Assessment Manual For Psychopharmacology; pp. 218–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangadhar BN, Varambally S. Yoga as therapy in psychiatric disorders: Past, present, and future. Biofeedback. 2011;39:60–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: The research evidence. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deslandes A, Moraes H, Ferreira C, Veiga H, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. Exercise and mental health: Many reasons to move. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59:191–8. doi: 10.1159/000223730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]