Abstract

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use appears to be increasing in children with developmental disorders. However, it is not clear whether parents perceive their healthcare providers as resources who are knowledgeable about CAM therapies and are interested in further developing their knowledge.

Objectives

(1) To establish and compare use of, and perceived satisfaction with, traditional medicine and CAM in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and (2) to assess parental perceptions of physician knowledge of CAM and physician interest in continuing education about CAM for the two groups of parents.

Methods

Families of children with a diagnosis of ADHD or ASD were surveyed regarding the frequency of use of traditional treatment and CAM, parental perceptions of the helpfulness of each therapy, parental perceptions regarding physicians' knowledge level about CAM, and physician interest in continuing education.

Results

Thirty-six percent (n=135) of 378 surveys were returned: 41 contained a diagnosis of ADHD and 22 of ASD. Traditional therapies were used by 98% of children with ADHD and 100% of those with ASD. Perceived helpfulness of medication was 92% for children with ADHD and 60% for children with ASD (p<0.05). CAM was used for 19.5% of children with ADHD and 82% of children with ASD. Perceived satisfaction for any form of CAM in the children with ADHD was at an individual patient level. Satisfaction for two of the most commonly used CAM treatments in children with ASD ranged from 50% to 78%. In children with ASD (the diagnostic group with the highest use of and satisfaction with CAM), physician's perceived knowledge of CAM was lower (14% versus 38%; p<0.05), as was perceptions of the physician's interest in learning more (p<0.05).

Conclusion

CAM use is significant, especially in children with ASD. Physicians are not perceived as a knowledgeable resource.

Introduction

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as a group of diverse medical healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not currently considered to be part of conventional medicine.1 The use of CAM is increasing, especially for conditions without effective medical treatment, or those for which medical treatment is associated with serious adverse effects.2 An estimated $21.2 billion was spent on CAM in 1997 alone.2

CAM use has been documented in all age groups for chronic health problems, such as cancer, arthritis2, allergies, asthma, and others.3 However, children with developmental disabilities tend to be higher users of CAM, perhaps because of their young age, lack of effective treatments, and greater concern about the adverse effects of traditional medications. CAM is used in 30%–70% of children with special healthcare needs.2 Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are among the most common users.2,4 Although families are encouraged to discuss their intention to use or interest in using CAM with their child's primary care physician,5 not all do so.6 Moreover, a national survey of pediatricians indicated that few routinely elicit this information or feel very knowledgeable about CAM.7 Thus, although the American Academy of Pediatrics has been an advocate for having pediatricians increase their knowledge of CAM and their ability to counsel families,2,8 it is not clear whether parents actually perceive their healthcare providers as professional resources who are knowledgeable about CAM therapies.

Because using CAM without provider guidance may lead to use of therapies that are potentially harmful,9 this study sought to determine the relative use of, and satisfaction with, CAM in two common diagnoses of developmental disability, ADHD and ASD. Another objective was to determine whether the level of dissatisfaction with conventional treatments was associated with use of CAM, which CAM treatments families turn to, and how knowledgeable parents perceived their physicians to be.

The study hypotheses were as follows: (1) that CAM use, relative to the use of traditional therapies, varied by diagnostic category, as did perceptions of helpfulness of these therapies and (2) that perception of provider knowledge of, and interest in, learning more about CAM was lowest in the diagnostic category where need and use were greatest.

Methods

Participants for this cross-sectional study were recruited from among the parents/caregivers of the patient panel of Kapila Seshadri, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Child Neurology and Neurodevelopmental Disabilities at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey–Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. The institutional review board exempted this study from review. Participants were recruited and data gathered via surveys mailed to caregivers. Each survey was accompanied by a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study and emphasizing that participation was voluntary and anonymous. No identifiers were associated with returned surveys. Caregivers were informed in the cover letter that in completing and returning the survey, they were giving consent for their responses to be used in the study.

Participants completing the survey were asked to provide demographic data regarding the age of the patient, gender, racial/ethnic background, age at diagnosis, and perceived disease severity. They were also asked to provide information on the ages of the parents/caregivers, level of caregiver education, and caregiver occupation. Caregivers were then asked questions about their use of various traditional treatments for their child's condition, their perceptions regarding the efficacy of these treatments, and any perceived adverse effects. Traditional treatments listed included speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, early intervention, special education, and prescribed medications. Caregivers were then surveyed regarding their use of nontraditional treatments for their child's condition, their perceptions regarding their efficacy, and any perceived adverse effects. Nontraditional/alternative treatments listed included ingestible supplements, auditory integration therapy, sensory integration therapy, facilitated communication, music therapy, intravenous secretin, chelation therapy, treatments for Candida, and others as noted by the caregiver.

In addition to questions on the use of traditional and nontraditional/alternative treatments, caregivers were surveyed about their interest in research on alternative treatments and their willingness to have their child participate in a research study. They were also surveyed regarding their perceptions of the primary care physician's knowledge of alternative treatments and their perceptions regarding the primary care physician's interest in learning more about alternative treatments.

The major diagnoses solicited were ADHD and ASD. Data were categorized by patient diagnosis as reported by the parent. Because all questionnaires were de-identified, diagnosis and treatment were not independently corroborated. Categorical data were analyzed by chi-square or Fisher exact tests (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). A two-tailed p-value of 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

Results

Descriptive data for children with ADHD and ASD

Three hundred and seventy-eight questionnaires were mailed. Five (1%) were undeliverable. Of the remaining 373 surveys, 135 (36%) were completed and returned. Of these, 41 (31%) were from parents who reported that their child had a diagnosis of ADHD, and 22 (17%) were from parents who reported that their child had a diagnosis of ASD.

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 contains demographic data on the children in these two diagnostic groups: age, race, gender, parental ages, and parental education levels. The children with ADHD and the children with ASD did not differ for any of these variables. Children in both groups were approximately 11 years of age and were disproportionately white and male. The parents in both groups were in their early forties, and the majority had a college-level or advanced degree.

Table 1.

Patient and Family Characteristics

| Population characteristics | ADHD (n=41) | ASD (n=22) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age±SD (y) | 10.9±3.2 | 10.9±5.5 | 1.0 |

| White race (95% CI) (%) | 78 (62–89) | 68 (45.85) | 0.39 |

| Male gender (95% CI) (%) | 76 (59–87) | 68 (45–85) | 0.53 |

| Mean maternal age±SD (y) | 41.6±5.3 | 43.1±6.2 | 0.32 |

| Mean paternal age±SD (y) | 44.5±5.5 | 44.9±7.0 | 0.8 |

| Maternal education (95% CI) (%)a | |||

| Less than high school | 7.5 (2–21) | 4.5 (0.2–25) | |

| High school | 25 (13–42) | 22.7 (9–46) | 0.36 |

| College | 32.5 (19–49) | 54.5 (33–75) | |

| Advanced degree | 35 (21–52) | 18.2 (6–41) | |

| Paternal education (95% CI) (%)a | |||

| Less than high school | 0.3 (3–25) | 4.5 (0.2–25) | 0.90 |

| High school | 30.8 (18–48) | 27.3 (12–50) | |

| College | 28.2 (16–45) | 31.8 (15–55) | |

| Advanced degree | 30.8 (18–48) | 36.4 (18–59) | |

Parental education level for ADHD group based on 40 of 41 maternal responses and 39 of 41 paternal responses.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Use of traditional and CAM therapies

Table 2 presents the percentage of patients in each diagnostic category who used the specific traditional or CAM treatments indicated, along with the percentage of users for whom the parents perceived each treatment to be helpful.

Table 2.

Parental Use of and Satisfaction with Traditional and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatment in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder or Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Treatment | ADHD use (n=41) | Perceived helpfulness by ADHD parents | ASD use (n=22) | Perceived helpfulness by ASD parents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional treatment | ||||

| Medication | 38 (93)* | 35 (92)** | 15 (68) | 9 (60) |

| Special education | 17 (41) | 16 (94) | 20 (91)* | 18 (90) |

| Speech/physical/ occupational therapy | 12 (29) | 11 (92) | 22 (100)* | 20 (91) |

| Early intervention | 9 (22) | 9 (100) | 19 (86)* | 15 (79) |

| Complementary/ alternative treatment | ||||

| Dietary supplements | 6 (15) | 1 (17) | 12 (55)* | 6 (50) |

| Sensory integration | 1 (2) | NA | 9 (41) | 7 (78) |

| Auditory integration | 0 | – | 4 (18) | 2 (50) |

| Facilitated communication | 1 (2) | NA | 3 (14) | 2 (67) |

| Music therapy | 0 | – | 3 (14) | 1 (33) |

| Candida therapy | 0 | – | 3 (14) | 1 (33) |

| Gluten casein–free diet | 0 | – | 2 (9) | 1 (50) |

| Intravenous secretin | 0 | – | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Kinesiology | 1 (2) | 1 (100) | 0 | – |

| Behavior modification | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (100) |

| Vision therapy | 0 | – | 1 (5) | 1 (100) |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) of respondents. All categories with the exception of gluten casein–free diet, kinesiology, behavior modification, and vision therapy were presented on the survey; the exceptions were provided by the parent in response to the request to list other forms of therapy.

p<0.05 in comparison of use between ADHD and ASD groups.

p<0.05 in comparison of helpfulness between ADHD and ASD groups. Statistical comparisons were made only in categories with more than single-case use.

NA, not available.

For the group with ADHD, traditional therapy use ranged from 93% for medication (the only traditional therapy used by more than half of these cases) to 22% for early intervention. The perceived efficacy of traditional therapies ranged from 100% for early intervention to 92% for medications. There were 76 reports of traditional therapy use. These were accounted for by 40 of the 41 cases (98%). The mean number of traditional therapies±standard deviation per user was 1.9±1.1.

In contrast to traditional therapies, CAM therapy use by children with ADHD was lower, ranging from 15% for dietary supplements to none in 6 of the 11 categories. The remaining four categories had single-case use; thus, perceived efficacy for each of these therapies represents the comment of a single case. For the most frequently used CAM category in children with ADHD, perceived efficacy was 17%, placing it below the satisfaction levels of the traditional therapies. In all, there were 10 instances of reported use of any form of CAM therapy by children with ADHD, and these instances were accounted for by 8 of the 41 cases (19.5%). The average number of CAM therapies per user was 1.3±0.5.

For children with ASD, traditional therapy use ranged from 100% for speech, physical, or occupational therapy to 68% for medication. Compared with children with ADHD, medication use by children with ASD was significantly lower (p<0.05), whereas special education, speech, physical, and occupational therapy and early intervention use was significantly higher (p<0.05). Among users, the perceived efficacy for the group of children with ASD was highest for speech/physical and occupational therapy (91%) and lowest for medication (60%). Compared with the group with ADHD, perceived efficacy of medication use was significantly lower (p<0.05). There were 76 reports of traditional therapy use by the 22 children with ASD (100%). The average number of therapies per user, 3.5±0.7, was thus higher for the group with ASD than for the group with ADHD noted above (p<0.001).

Ingested dietary supplements, the most common CAM therapy for children with ASD, were used by 12 (55%) of these children. These 12 children accounted for 30 reports of dietary supplement use, indicating that individual children used more than one supplement. Of the 12 children, 58.3% reported use of vitamin B6 plus magnesium; 50%, dimethylglycine, 33.3%, flaxseed; 33.3%, omega-3; 25%, Defeat Autism Now (DAN)-based dietary supplements; 16.7%, probiotics; and 8.3% each, calcium, zinc, cod liver oil, and enzymes. Table 3 presents use calculated as a proportion of all 22 children with ASD.

Table 3.

Dietary Supplements Used by Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Dietary supplement | ASD patients using supplement (n=22) (95% CI) (%)a |

|---|---|

| Vitamin B6+magnesium | 31.8 (15–55) |

| Dimethylglycine | 27.2 (12–50) |

| Flaxseed | 18.2 (6–41) |

| Omega-3 | 18.2 (6–41) |

| DAN-based dietary supplements | 13.6 (4–36) |

| Probiotics | 9.1 (2–31) |

| Calcium | 0.8 (0.2– 25) |

| Zinc | 0.8 (0.2–25) |

| Cod liver oil | 0.8 (0.2–25) |

| Enzymes | 0.8 (0.2–25) |

Supplements were used by 12 of 22 (55%) children with ASD. These 12 children accounted for 30 reports of using a supplement, indicating that individuals used more than one supplement.

DAN, Defeat Autism Now.

The least common CAM therapies were intravenous secretin, behavior modification, and vision therapy, each of which was used by one child, and kinesiology, which no patient used (Table 2). In CAM categories with more than single-child use, the highest perceived efficacy was for sensory integration therapy (78%). In all, the 39 instances of reported use of CAM therapies were accounted for by 18 of the 22 children with ASD, making the proportion of children using CAM significantly higher for children with ASD than for children with ADHD (82% versus 19.5%; p<0.0001). The average number of CAM therapies per user, 2.2±1.1, was also higher for children with ASD than for children with ADHD, as noted above (p<0.05).

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the relationship between prescribed medication use and use of the more common CAM therapies, noting a nonsignificant trend toward more CAM therapy use by the children who did not use prescribed medication. Of the 15 children with ASD who used medication, 7 (46.7%) also used dietary supplements. In contrast, in the 7 children with ASD who did not use medication, there was a higher percentage of dietary supplement use (5 of 7; 71.4%). A similar relationship was noted between medication use and sensory integration therapy, the second most commonly used CAM therapy by children with ASD. In this instance, 25.7% of the children who used medication also used sensory integration therapy, whereas 71.4% of the children who did not use medication used sensory integration therapy (p=0.07).

Parental perception of primary care physician's knowledge and interest

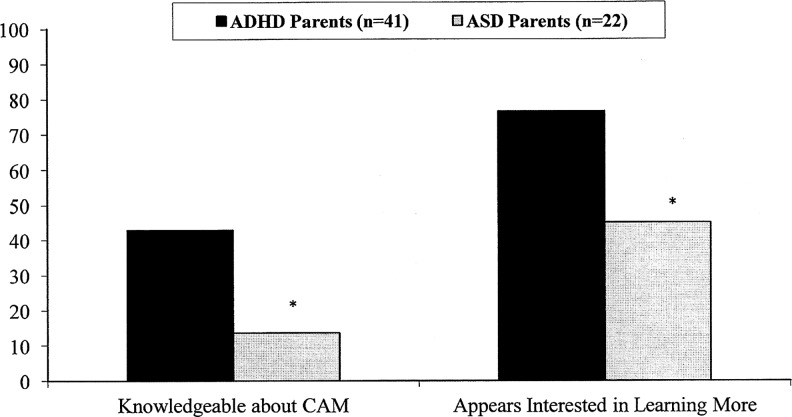

Figure 1 compares parents of children with ADHD and parents of children with ASD with respect to their perceptions of the primary care physician's knowledge of CAM and interest in learning more about CAM. A smaller proportion of parents of children with ASD compared with parents of children with ADHD perceived their physicians to be knowledgeable and interested in CAM (p<0.05). However, parents in both categories were similar in that more rated the primary care physician as interested rather than knowledgeable.

FIG 1.

Comparing perceptions by parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) of physician knowledge of and interest in learning about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). ADS data are based on yes/no replies by 20 of 22 ASD parents to question on physician interest in learning; ADHD data are based on yes/no replies by 35 of 41 parents to question on physician knowledge and 34 of 41 parents to question on physician interest in learning. *p<0.05.

Parental interest in research

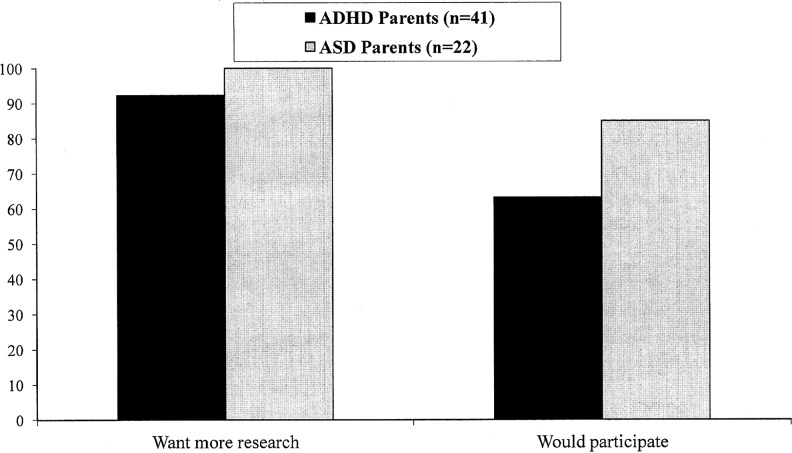

As noted in Figure 2, more than 90% of both parents of children with ADHD and ASD wanted to see more research into CAM. Although parents were more likely to advocate for research than to have their children actually participate in such research, over two thirds of both groups of parents did report a willingness to participate in research.

FIG 2.

Comparing parental desire for and willingness to have their children participate in research on alternative treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). ASD data are based on yes/no replies by 20 of 22 ASD parents to question on participation; ADHD data are based on yes/no replies by 39 of 41 parents to question on wanting more research and 38 of 41 patients to question on participation.

Discussion

Families of children with ADHD and ASD pursued multiple treatments that included both traditional and CAM therapies. However, patterns of use of traditional and CAM therapy varied with diagnostic category, with a higher proportion of parents of children with ASD opting for, and expressing satisfaction, with CAM, compared with parents of children with ADHD. This may in part be because there are fewer effective traditional treatments for ASD compared with ADHD.

Intravenous secretin and vision therapy were the least used among CAM treatments, perhaps because these interventions have been formally studied and established to be ineffective.10–12 These preferences suggest that parents can make more informed choices and decisions when adequate scientific data are made available. In the current study, parental desire for information was reflected in their interest in research pertaining to CAM treatments, with more than 90% of the parents of children with ADHD and ASD wanting to see more research. Less than 20% of the parents of children with ASD, the group with the highest use of CAM, described their healthcare providers as knowledgeable. Moreover, fewer than 50% of these parents perceived their physicians to be interested in learning more. These findings are of concern given the growing use of CAM and a recent survey documenting parental interest in receiving counseling from their providers about CAM.2,13 The current findings can be used by healthcare providers to better serve their patients by fostering further research into traditional and CAM treatments and by increasing their knowledge level of the existing treatments.2,7 The recommendations of the Task Force on Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the American Academy of Pediatrics support this view.2 More randomized controlled trials of CAM therapies are emerging,14,15 along with new recommendations for methodologic approaches to the study of CAM.16 CAM research and knowledge are advocated by the American Academy of Pediatrics and are being implemented for physicians in training;17 thus, promotion of research and knowledge has become more feasible.

The current study was similar to those of Chan et al.18 and Levy et al.9 in terms of identifying frequency of CAM use in diagnoses of ADHD and ASD, respectively. However, this study also compared use between these diagnoses and surveyed parental perception of helpfulness. The study was limited by the low response rate and subsequent small sample size. The participants were derived from one medical practice, which may have biased the results as well. These results may not be generalizable to all physician populations who see children with ADHD and ASD, but the results show that further study on a much larger scale is warranted.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Huang, Dr. Seshadri, Dr. Matthews, and Dr. Ostfeld have no commercial associations with any of the CAM treatments discussed in the article.

References

- 1.National Institute of Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. What is Complementary in Alternative Medicine (CAM)? 2012. www.NCCAM.NIH.gov. [Jan 14;2013 ]. www.NCCAM.NIH.gov [home page on Internet]

- 2.Kemper KJ. Vohra S. Walls R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1374–1386. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouster-Stevens K. Nageswaran S. Arcucy TA. Kemper KJ. How do parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritic (JIA) perceive their therapies? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong HH. Smith RG. Patterns of complementary and alternative medical therapy use in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy SE. Hyman SL. Use of complementary and alternative treatments for children with autistic spectrum disorders is increasing. Pediatr Ann. 2003;32:685–691. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20031001-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha D. Efron D. Complementary and alternative medicine use in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:23–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemper KJ. O'Connor KG. Pediatricians' recommendations for complementary and alternative medical therapies. Ambulator Pediatr. 2004;4:482–487. doi: 10.1367/A04-050R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Complementary and Integrative Medicine and Council on Children with Disabilities. Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1186–1189. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy SE. Mandell DS. Merhar S. Ittenback RF. Pinto-Martin JA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among children recently diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:418–423. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnaswami S. McPeeters ML. Veenstra-Vander Weele J. A systematic review of secretin for children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1322–e1325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett B. A critical evaluation of the evidence supporting the practice of behavioural vision therapy. Ophthal Physiol Optics. 2009;29:4–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumgaertel A. Alternative and controversial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:977–992. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liptak GS. Orlando M. Yingling JT, et al. Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with developmental disabilities. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong SS. Cho SH. Acupuncture for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:173. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpouzis F. Pollard H. Bonello R. A randomized control trial of the Neuro Emotional Technique (NET) for childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a protocol. Trials. 2009;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aickin M. Comparative effectiveness research and CAM. J Altern Comp Med. 2010;16:1–2. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vohra S. Surette S. Mittra D. Rosel LD. Gardiner P. Kemper KJ. Pediatric integrative medicine: pediatrics' newest subspecialty? BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan E. Rappaport LA. Kemper KJ. Complementary and alternative therapies in childhood attention and hyperactivity problems. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:4–8. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]