Abstract

BACKGROUND

The authors assessed patterns of perioperative chemotherapy use in elderly patients with resected stage I, II, or IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from 1992 to 2002.

METHODS

By using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 11,807 patients were identified who had resected stage I, II, or IIIA NSCLC between 1992 and 2002 and survived ≥120 days beyond diagnosis. The rate of perioperative chemotherapy use was measured by calendar year, and the association between clinical/demographic characteristics and the receipt of chemotherapy was examined by using logistic regression.

RESULTS

In total, 957 patients with stage I, II, or IIIA NSCLC (8.1% of the study population) received perioperative chemotherapy. The proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy for stage I NSCLC changed little during the study period. Of 3230 patients with stage II and IIIA NSCLC, 609 patients (18.9%) received chemotherapy, 423 patients (13%) received chemotherapy combined with radiation. 452 patients (15.6%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, and 66 patients (2.3%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The use of chemotherapy increased significantly among patients who were diagnosed after 1994 relative to patients who were diagnosed in 1992 after controlling for sociodemographic and treatment characteristics (P <.001). There was significantly increased use of new-generation chemotherapy agents, such as carboplatin and taxanes (P <.001). The proportion of patients receiving combined-modality therapy also increased significant (P <.001). Younger age, being married, having advanced-stage tumor or adenocarcinoma, having a later diagnosis year, receiving radiation, and seeing an oncologist were predictors for the receipt of chemotherapy (P <.001).

CONCLUSIONS

A substantial proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with NSCLC received perioperative chemotherapy. Specifically designed prospective trials that focus on older patients are needed.

Keywords: Medicare beneficiaries, nonsmall cell lung cancer, chemotherapy, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database

Lung cancer is the most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related death in the U.S., with 174,470 new diagnoses and 163,460 deaths in 2006.1 The majority of patients with lung cancer have nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).2 The most effective treatment for stage I, II, and IIIA NSCLC is surgical resection. Despite surgical resection, from 50% to 60% of patients relapse and die from their lung cancer.3 Systemic recurrence has been reported as the most frequent type of failure in patients with NSCLC,4 and it is postulated that >75% of deaths are related to disease relapse, especially distant metastases.5 Because of these recurrences, the 5-year survival rate of patients with early-stage NSCLC, despite complete resection, ranges from 45% to 70%.5,6 After other solid cancers (ie, breast, colon), effective adjuvant therapy theoretically should include systemic chemotherapy. Many attempts have been made in the past to reduce the risk of relapse and death from lung cancer by administering adjuvant chemotherapy to patients after surgical resection.

In 1995, a meta-analysis of postoperative chemotherapy in NSCLC by the British Medical Council indicated a 13% reduction in the hazard of death, leading to a 5% absolute improvement in survival 5 years after the start of adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy compared with observation only.7 Although this trend did not reach statistical significance, the findings led to multiple national and international trials that were powered adequately to find an absolute benefit of 5% at 5 years. Results of these trials have been reported in the last 5 years.8–16

In 2003, the abstract of the International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial (IALT) study, which was presented at the Annual Meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology, first demonstrated a survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy.8 In 2004, chemotherapy became the standard of care in the U.S., when the IALT trial demonstrated that, compared with surgery alone, cisplatin-based adjuvant therapy improved the 5-year survival rate by 40% to 44.5% in patients with resected NSCLC.9

To our knowledge, there is little information regarding the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with resectable NSCLC outside clinical trials. It is known that the elderly are underrepresented in clinical trials.17 For example, the median age in the IALT trial was 59 years (range, 27–77 years).8,9 We used data from the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database to study the trend in receipt of chemotherapy during the decade from 1992 to 2002 to investigate factors associated with use of perioperative chemotherapy among elderly patients with resected NSCLC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source and Cohort

The study cohort was comprised of patients who were registered in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program from 1992 to 2002. The SEER Program collects uniformly reported data from 11 population-based cancer registries covering approximately 14% of the U.S. population.18 For each incident cancer, the SEER registries collect information on patients’ tumor characteristics, demographic characteristics, and month and year of diagnosis. Since 1991, SEER data have been merged with Medicare administrative data by a matching algorithm that has successfully linked files for >94% of SEER registry patients who were diagnosed at age ≥65 years. The Medicare claims files contain extensive diagnostic, treatment, and cost data for patients who are covered by Medicare. In 1993, these 2 databases were linked.19

We identified 34,511 patients aged >66 years who were diagnosed with NSCLC between 1992 and 2002 (SEER codes 34.0–34.9 and International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Second edition [ICD-O-2] morphology codes 8010–8040, 8050–8076, 8140, 8250–8260, 8310, 8320, 8323, 8430, 8470–8490, 8550–8573, 8980, and 8981). We excluded patients without Medicare Part A and Part B coverage during the year before and the 120 days after diagnosis and those who were members of a health maintenance organization (n = 9709 patients for both exclusions).

Identification of Staging and Surgical Procedures

We defined resection surgery as wedge resection, pneumonectomy, or lobectomy that occurred within 4 months after the diagnosis of NSCLC from both the site-specific surgery code in SEER and Medicare claims. The IDC ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were taken from outpatient and inpatient billing claims and were used to define the following procedures: pneumonectomy (ICD9-CM codes 32.50 and 32.60; CPT codes 32,440, 32,442, and 32,445), lobectomy (ICD9-CM code 32.40; CPT codes 32,480, 32,482, 32,484, and 32,486), and wedge resection (ICD9-CM codes 32.29 and 32.30; CPT code 32,500). Of 24,802 patients who met the selection criteria, 11,807 patients underwent resection.

Identification of Chemotherapy and Radiation Treatment

We used the Health Care Financing Administration’s Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) to identify patients who received a specific chemotherapeutic drug within 120 days after their NSCLC diagnosis according to their physician claims or their hospital outpatient claims files. We chose the 120-day window to differentiate initial adjuvant treatment from treatment at relapse. In addition, using Level II HCPCS codes (J9XXX, 96,400–96,549), ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes (V581, V662, and V672), revenue codes (0331, 0332, and 0335), and a procedure code (9925) from physician claims files or outpatient or admission hospital claims, we searched for evidence of other chemotherapy delivery. Among patients without specific J9XXX chemotherapy HCPCS codes, these codes were used to capture evidence that an unspecified chemotherapeutic drug had been given during the 120 days after diagnosis. We defined radiation therapy within 120 days after cancer diagnosis through the radiation code in SEER and Medicare claims.

Identification of Patients Seeing a Medical Oncologist

We defined the patient as one who “saw a medical oncologist” if the patient had a physician claim within the 4-month period from the month of diagnosis and the physician specialty (primary or secondary) was medical oncology or hematology based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The physician claims have a 2-digit CMS provider specialty code (90 for medical oncologist, 83 for hematology oncologist) that represents the specialty reported to the carrier who processed the claim.18

Definition of Explanatory Variables

Our analysis of use of adjuvant chemotherapy by year was adjusted by the following patient-level variables: sex, race, marital status, age at diagnosis, American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, tumor grade, histology type, and SEER site. The socioeconomic characteristics of each patient were based on the percentage of adults with <12 years of education and the percentage of residents living below the poverty level from census tract data. To assess the prevalence of comorbid disease in our cohort, we calculated the Charlson comorbidity index by identifying billing codes for various conditions during the year before diagnosis of cancer using the Deyo implementation of the Charlson score applied to both inpatient and outpatient claims.19 Hospital affiliation with a medical school was available from the SEER-Medicare Hospital file and was categorized as no, limited, graduate, and major affiliation. The number of beds at each hospital also was available from the SEER-Medicare Hospital file.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.13; SAS Inc., Cary, NC). We measured the proportion of patients with resected NSCLC who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy in each calendar year stratified by stage. We performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to evaluate the association between other clinical and demographic characteristics and adjuvant chemotherapy use. Covariates included sex, race, age, marital status, SEER registry, median household income, tumor stage at diagnosis, tumor grade, and histology.

RESULTS

Receipt and Predictors of Perioperative Chemotherapy

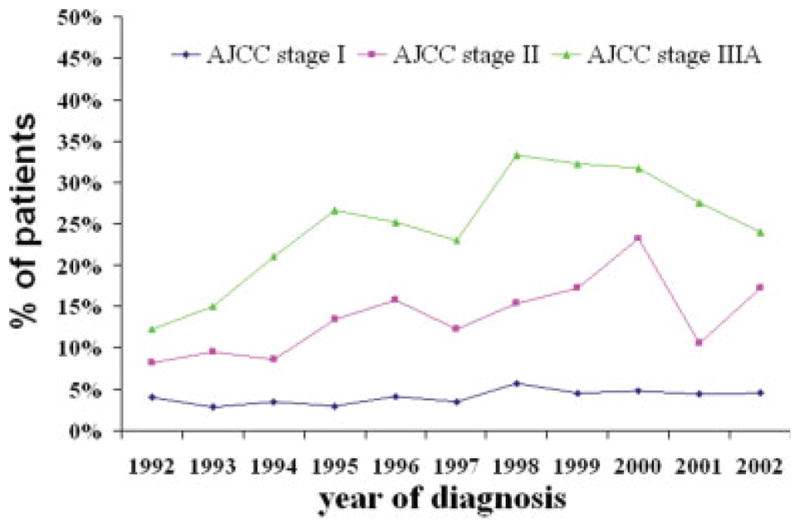

In total, 11,807 patients with stage I, II, or IIIA underwent surgical resection during the study period. Among them, 957 patients (8.1% of the study population) received perioperative chemotherapy. The proportion of patients with stage I NSCLC receiving chemotherapy changed little over the study period (Fig. 1). Next, we focused our attention on the 3230 patients with stage II or IIIA NSCLC who underwent resection. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of those 3230 patients and the percentage in each subgroup who received chemotherapy. Overall, 609 patients (18.9%) received perioperative chemotherapy. Chemotherapy was delivered postoperatively to 15.6% of patients and preoperatively to 2.3% of patients. Combined-modality therapy (chemotherapy and radiation therapy) were delivered to 423 patients (13%), and chemotherapy alone was delivered to 186 patients (5.8%).

FIGURE 1.

Time trends in Medicare claims for perioperative chemotherapy by stage during the period from 1992 to 2002. AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on Cancer.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Resected Stage II, IIIA Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer and the Percentage Treated With Adjuvant Chemotherapy During the Period 1992–2002

| Characteristic | Total no. of patients | Adjuvant chemotherapy

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | % | |||

| Total | 3230 | 609 | 18.9 | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 66–69 | 938 | 242 | 25.8 | <.0001 |

| 70–74 | 1148 | 227 | 19.8 | |

| 75–79 | 787 | 108 | 13.7 | |

| ≥80 | 357 | 32 | 9 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 1804 | 349 | 19.3 | .4219 |

| Women | 1426 | 260 | 18.2 | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 2793 | 534 | 19.1 | .4837 |

| Black | 164 | 33 | 20.1 | |

| Hispanic | 99 | 15 | 15.2 | |

| Other/unknown | 174 | 27 | 15.5 | |

| AJCC stage | ||||

| II | 1624 | 216 | 13.3 | <.0001 |

| IIIA | 1606 | 393 | 24.5 | |

| Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 169 | 34 | 20.1 | .1625 |

| Moderate differentiated | 953 | 167 | 17.5 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1788 | 334 | 18.7 | |

| Unknown | 320 | 74 | 23.1 | |

| Histologic type | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1025 | 157 | 15.3 | .0003 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1257 | 270 | 21.5 | |

| Bronchioalveolar | 206 | 29 | 14.1 | |

| Others | 742 | 153 | 20.6 | |

| SEER region | ||||

| San Francisco | 224 | 30 | 13.4 | .0011 |

| Connecticut | 510 | 83 | 16.3 | |

| Michigan | 574 | 139 | 24.2 | |

| Hawaii | 86 | 13 | 15.1 | |

| Iowa | 398 | 62 | 15.6 | |

| New Mexico | 101 | 14 | 13.9 | |

| Seattle | 362 | 73 | 20.2 | |

| Utah | 56 | 7 | 12.5 | |

| Georgia | 206 | 50 | 24.3 | |

| San Jose | 161 | 35 | 21.7 | |

| Los Angeles | 552 | 103 | 18.7 | |

| Census tract education (% of adults with<12 y of education) | ||||

| <11 | 694 | 141 | 20.3 | .2164 |

| 11–18 | 696 | 137 | 19.7 | |

| 18–26 | 673 | 124 | 18.4 | |

| ≥26 | 696 | 113 | 16.2 | |

| Census tract poverty level (% living below the poverty line) | ||||

| <3.5 | 728 | 155 | 21.3 | .1170 |

| 3.5–6.5 | 708 | 117 | 16.5 | |

| 6.5–12 | 666 | 118 | 17.7 | |

| ≥12 | 657 | 125 | 19 | |

| Comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 2158 | 429 | 19.9 | .1945 |

| 1 | 719 | 123 | 17.1 | |

| 2 | 242 | 38 | 15.7 | |

| ≥3 | 111 | 19 | 17.1 | |

| Married | ||||

| No | 1223 | 194 | 15.9 | .0007 |

| Yes | 2007 | 415 | 20.7 | |

| Metropolitan area | ||||

| No | 396 | 75 | 18.9 | .9632 |

| Yes | 2834 | 534 | 18.8 | |

| Teaching hospital* | ||||

| Major | 1127 | 181 | 16.1 | .0362 |

| Limited/graduate | 673 | 106 | 15.8 | |

| No affiliation | 1098 | 216 | 19.7 | |

| No. of hospital beds* | ||||

| <350 | 1231 | 226 | 18.4 | .2209 |

| ≥350 | 1667 | 277 | 16.6 | |

| Seeing oncologists | ||||

| Yes | 1540 | 485 | 31.5 | <.0001 |

| No | 1690 | 124 | 7.3 | |

AJCC indicates American Joint Committee on Cancer; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 9% of patients, surgical procedures could not be found in inpatient claims from 1 month before to 4 months after lung cancer diagnosis.

Younger patients were more likely than older patients to receive chemotherapy. For patients ages 66 to 69 years and aged ≥80 years, chemotherapy use declined from 25.8% to 9% (P <.0001). Among patients who had stage II NSCLC, 13.3% received chemotherapy compared with 24.5% of patients who had stage IIIA NSCLC (P <.0001). In addition to age and advanced stage, having an adenocarcinoma histology (P <.0001), having a later diagnosis year (P <.0001), being married (P <.0001), receiving radiation (P <.0001), and seeing an oncologist (P <.0001) were associated with chemotherapy use in univariate analysis (Table 1). Multivariate analyses generally confirmed the results of the univariate analyses (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Factors Associated With the Receipt of Chemotherapy in Patients With Stage II, IIIA Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer

| Characteristic | Receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: OR (95% CI)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Model I | Model II | |

| Age | ||

| Every 5 y | 0.67 (0.60–0.75) | 0.68 (0.61–0.77) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Women | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.87 (0.55–1.37) | 1.00 (0.62–1.62) |

| Hispanic | 0.61 (0.33–1.12) | 0.58 (0.30–1.09) |

| Other/unknown | 0.69 (0.41–1.17) | 0.72 (0.41–1.26) |

| AJCC stage | ||

| II | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| IIIA | 1.79 (1.47–2.18) | 1.74 (1.42–2.14) |

| Grade | ||

| Well differentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate differentiated | 0.78 (0.50–1.22) | 0.91 (0.57–1.46) |

| Poorly differentiated | 0.78 (0.51–1.20) | 0.88 (0.56–1.38) |

| Unknown | 0.99 (0.60–1.63) | 1.09 (0.64–1.85) |

| Histologic type | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.57 (1.24–1.99) | 1.42 (1.11–1.82) |

| Bronchioalveolar | 0.98 (0.61–1.57) | 0.90 (0.55–1.47) |

| Others | 1.40 (1.07–1.84) | 1.39 (1.04–1.85) |

| SEER region | ||

| Utah | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| San Francisco | 1.47 (0.58–3.73) | 2.03 (0.77–5.32) |

| Connecticut | 1.70 (0.71–4.10) | 2.31 (0.93–5.71) |

| Michigan | 2.78 (1.17–6.57) | 2.95 (1.22–7.15) |

| Hawaii | 1.64 (0.52–5.14) | 1.46 (0.44–4.78) |

| Iowa | 1.68 (0.70–4.04) | 1.61 (0.65–3.96) |

| New Mexico | 1.44 (0.52–4.01) | 1.44 (0.50–4.15) |

| Seattle | 2.47 (1.03–5.95) | 2.87 (1.16–7.07) |

| Georgia | 2.88 (1.17–7.12) | 2.28 (0.90–5.78) |

| San Jose | 2.83 (1.12–7.15) | 3.99 (1.53–10.43) |

| Los Angeles | 2.59 (1.09–6.15) | 2.37 (0.98–5.77) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 1992 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1993 | 1.43 (0.85–2.14) | 1.29 (0.74–2.23) |

| 1994 | 1.89 (1.14–3.12) | 1.84 (1.08–3.11) |

| 1995 | 2.57 (1.57–4.21) | 1.90 (1.13–3.19) |

| 1996 | 2.84 (1.75–4.63) | 2.14 (1.28–3.57) |

| 1997 | 2.44 (1.48–4.03) | 1.77 (1.05–2.99) |

| 1998 | 4.10 (2.50–6.72) | 2.87 (1.71–4.84) |

| 1999 | 4.43 (2.66–7.38) | 3.40 (1.98–5.82) |

| 2000 | 4.72 (2.85–7.83) | 3.57 (2.09–6.09) |

| 2001 | 3.44 (1.85–6.38) | 2.30 (1.20–4.40) |

| 2002 | 4.22 (2.11–8.43) | 2.77 (1.33–5.76) |

| Comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 0.84 (0.65–1.07) |

| 2 | 0.77 (0.52–1.14) | 0.73 (0.49–1.10) |

| ≥3 | 0.85 (0.50–1.45) | 0.81 (0.46–1.42) |

| Married | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.32 (1.07–1.64) | 1.29 (1.03–1.61) |

| Census tract poverty level (% living below the poverty line) | ||

| <3.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3.5–6.5 | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) | 0.76 (0.56–1.04) |

| 6.5–12 | 0.88 (0.65–1.19) | 0.81 (0.59–1.12) |

| ≥12 | 1.02 (0.74–1.42) | 1.06 (0.75–1.49) |

| Teaching hospital* | ||

| Major | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Limited/graduate | 1.02 (0.76–1.37) | 1.06 (0.78–1.45) |

| No affiliation | 1.20 (0.90–1.60) | 1.12 (0.83–1.51) |

| No. of hospital beds* | ||

| <350 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥350 | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) | 0.88 (0.68–1.13) |

| Radiation | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2.43 (1.98–2.98) | 2.15 (1.74–2.66) |

| Seeing oncologists | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 5.63 (4.46–7.10) | |

OR indicates odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 9% of patients, surgical procedures could not be found in inpatient claims from 1 month before to 4 months after lung cancer diagnosis.

In univariate analysis, certain geographic locations also were associated with a higher rate of adjuvant chemotherapy use, from a high of 24.2% in Michigan to a low of 12.5% in Utah (Table 1). In multivariate analyses, this variable became less significant (Table 2).

Receiving care in a nonteaching hospital also was associated with a higher rate of adjuvant chemotherapy use than receiving care in a teaching hospital in univariate analysis (Table 1). However, this factor became nonsignificant in multivariate analyses (Table 2). Sex, race, comorbidity, tumor grade, urban residence, income, education level, and hospital volume were not associated with use of perioperative chemotherapy after adjusting for other variables in this cohort of elderly patient with resected NSCLC (Table 2).

Trend and Frequency of Perioperative Chemotherapy Use

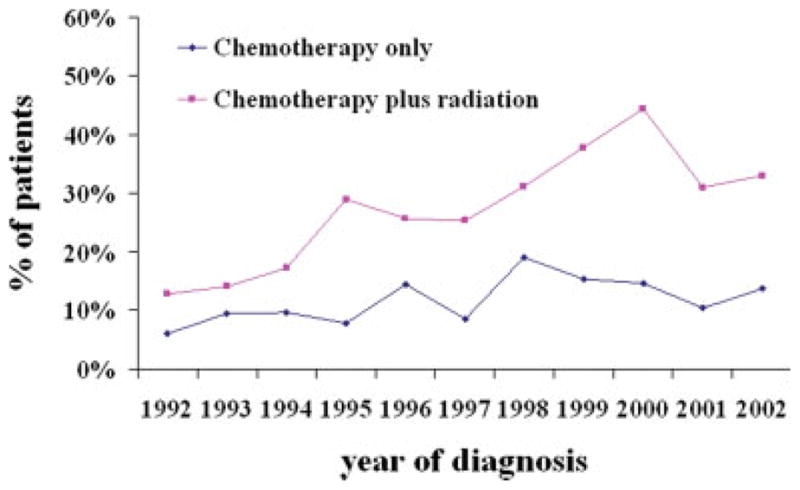

The proportion of patients who received perioperative chemotherapy and combination therapy changed significantly during the study period. The use of chemotherapy increased significantly in patients who were diagnosed in 1994 (odds ratio [OR], 1.89; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.41–3.12), 1995 (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.57–4.21), 1996 (OR, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.75–4.63), 1997 (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.48–4.03), 1998 (OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 2.50–6.72), 1999 (OR, 4.43; 95% CI, 2.66–7.38), 2000 (OR, 4.72; 95% CI, 2.85–7.83), 2001 (OR, 3.44; 95% CI, 1.85–6.38), and 2002 (OR, 4.22; 95% CI, 2.11–8.43) relative to the proportion of patients who were diagnosed in 1992 after controlling for sociodemographic and treatment characteristics (Table 2). Chemotherapy use initially increased in the early 1990s, reached to its peak around 1997/ 1998 for stage II and around 1999/2000 for stage IIIA, and slowly declined afterward. The use of chemotherapy in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC increased again around 2000 (Fig. 1). The time trend for the proportion of patients who received combined-modality therapy and chemotherapy alone is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Time trends in Medicare claims for perioperative chemotherapy or combined-modality therapy during the period from 1992 to 2002.

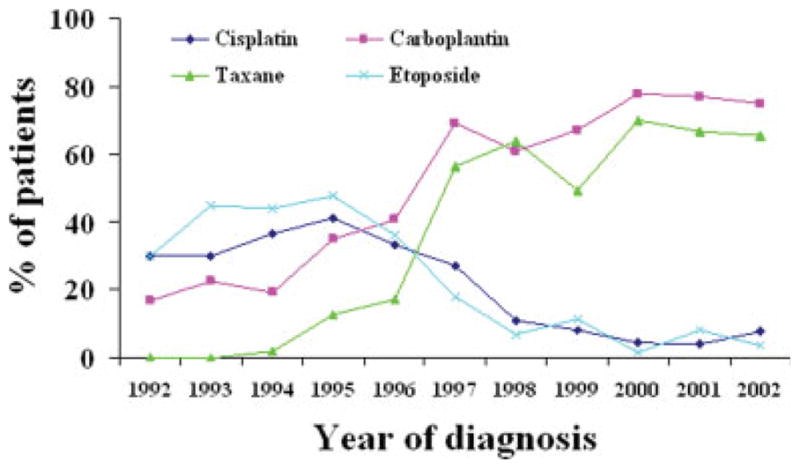

Type of Chemotherapeutic Agents Used

The proportion of patients receiving specific chemotherapeutic agents also changed significantly during the study period (Fig. 3), rising from 16.7% to 75% and from 0% to 65.4% for carboplatin and taxane, respectively, and declining from 45% to 3.85% and from 30% to 7% for etoposide and cisplatin, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Time trends in Medicare claims for specific chemotherapeutic agents for resected stage II, IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer during the period from 1992 to 2002.

DISCUSSION

The decision to use chemotherapy is complex in the face of uncertain benefit. Surveys reveal that individual physicians and types of specialists differ widely in their beliefs regarding chemotherapy.20,21 Because of the high risk of recurrence even in patients with resected NSCLC, clinicians are motivated strongly to add systemic therapy to surgery either preoperatively or postoperatively even in patients with early-stage disease.22,23 Some experts recommended adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with resected NSCLC in the absence of definitive data because of the great risk of distant recurrence.22,23 Some patients prefer aggressive treatment because of the perceived high risk of recurrence.24

In a population-based sample of Medicare beneficiaries with resected stage I, II, and IIIA NSCLC between 1992 and 2002, we observed that 8.1% of patients received perioperative chemotherapy. The use of chemotherapy increased significantly in patients who were diagnosed after 1994 relative to patients who were diagnosed in 1992 after controlling for sociodemographic and treatment characteristics. Our findings are consistent with recent studies of patterns of care in patients NSCLC conducted in the U.S. and other countries.25–27 A noteworthy observation from our study was that chemotherapy use initially increased and reached to its peak around 1997/1998 for stage II, around 1999/2000 for stage IIIA, and slowly declined afterward. Increased chemotherapy use in the 1990s corresponded temporally with publication of the British Medical Council’s meta-analysis, which demonstrated the moderate efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resected NSCLC.7 The later decline in the use of chemotherapy corresponded to the publication of several randomized trials, which failed to demonstrate the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy,16,28 suggesting that community practice is sensitive to new findings from clinical trials. However, some of those trials were criticized for being underpowered for detecting small benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy in this patient population.29

Chemotherapy use declined dramatically with increasing age at diagnosis, consistent with previous findings.30,31 This may be because of physicians’ perception of decreased chemotherapy tolerance or increased risks of toxicity in elderly patients.30 Older patients with lung cancer often are compromised by the surgery itself and have a prolonged recovery time compared with other cancer operations, such as mastectomy and colectomy. This may interfere with the receipt of chemotherapy. Elderly patients also may be reluctant to trade quality of life for a perceived survival benefit31 and may be more likely to refuse chemotherapy.32,33

We observed significant associations between disease stage and the receipt of chemotherapy. For patients with stage I disease, perioperative chemotherapy use was rare. This is in line with a recent updated analysis of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B trial, which failed to show a significant improvement in overall survival in patients with stage IB NSCLC.11 For patients with stage II or IIIA disease, chemotherapy use was greater and increased substantially by stage. This is consistent with the results from clinical trials in which increasing benefit was reported with advanced stage.5,6

We observed that married patients received chemotherapy more often, consistent with findings in other cancers.34,35 The reasons underlying treatment differences by marital status are unclear but may include encouragement or support from patients’ spouses in seeking aggressive treatment36 or the perception of a higher “value” of life in those patients with a spouse and dependents.36 Clinicians also may recommend aggressive therapies more often to married patients.

Patients who had a medical oncology referral were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy (adjusted OR, 5.63; 95% CI, 4.46–7.10). This is in agreement with other studies, which demonstrated that the decision to get a medical oncology referral is a key step in the eventual receipt of chemotherapy.37–39

From 1992 to 2002, the combination of chemotherapeutic agents also changed. Our results suggest that carboplatin and paclitaxel came into wide use as agents for patients with NSCLC in the U.S. This shift occurred despite lack of definitive data on the efficacy of these agents in the adjuvant setting. Tolerance and toxicity of chemotherapy is a major concern for elderly patient with lung cancer.40 Many elderly patients with NSCLC have difficulty tolerating cisplatin-based treatment because of its nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and neurotoxicity; cisplatin administration requires aggressive hydration that may be contraindicated in elderly patients because of their comorbidities. Furthermore, cisplatin is also one of the most emetogenetic drugs. The substitution of carboplatin in elderly patients is appealing.22 Although carboplatin does not possess activity equivalent to that of cisplatin in all platinum-sensitive tumors,41–43 carboplatin still may be an alternative to cisplatin in elderly patients who are poor candidates for cisplatin. With both activity and tolerability demonstrated in the treatment of advanced NSCLC,44,45 the taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) also became a popular option in the U.S.; with the increased use of newer chemotherapeutic agents, the use of older agents (cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and cisplatin) dropped to a low rate.

The best sequence of surgery and chemotherapy remains controversial. The majority of patients received chemotherapy postoperatively during the study period. The advantage of adjuvant chemotherapy includes no delay of tumor resection and precise pathologic staging. In addition, chemotherapy generally is more effective in treating minimal-volume disease compared with grossly apparent disease.29 The advantages of using neoadjuvant chemotherapy include earlier commencement of systemic therapy, allowing for the surgical resection of tumor that may not have been suitable for surgery at diagnosis. The potential disadvantages of neoadjuvant therapy include delaying potentially curative surgery and increasing postoperative morbidity and mortality.29

The patients in the current analysis were aged ≥66 years. To our knowledge, there have been no trials specifically assessing chemotherapy for NSCLC in older patients. In a subgroup analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group study JBR.10, adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin improved survival in patients aged >65 years with acceptable toxicity, even though elderly patients received less chemotherapy.46 The results from a meta-analysis of NSCLC7 indicated that the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was independent of age. We examined the association of chemotherapy with survival from lung cancer in the SEER-Medicare data.

There are major challenges to assessing treatment outcomes in observational data, most of which relate to selection biases. For example, a selection bias may be expected for patients with better underlying health to be more likely to receive chemotherapy.47 In our analyses, we used multivariable survival analyses and also controlled for propensity to treat. We also stratified the analyses into deaths from cancer versus deaths from other causes. In our analyses, patients with lung cancer who received chemotherapy experienced an approximate 33% lower mortality from noncancer causes. This indicates that there were strong residual selection biases that were not eliminated after controlling for potential confounders and propensity to receive chemotherapy. Consequently, the survival analyses lack validity, and we did not present them.

The current study has several strengths. First, the nationwide Medicare claims data offer a unique opportunity to study the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with NSCLC. Compared with clinical trials data, which are known to underrepresent elderly patients, population studies are more likely to represent all elderly patients in the real world. Second, this large, population-based study conducted in community-dwelling elderly patients accounted for 14% of the U.S. population. The sample size was large enough to allow us to draw conclusions regarding patterns of care in a diverse population and to examine several potentially confounding variables.

Our study had some limitations. First, the study findings may be applicable only to patients who were diagnosed with NSCLC at age ≥66 years who were not health maintenance organization members and had both Medicare Part A and Part B coverage. Chemotherapy use most likely was greater in patients aged <65 years. Second, administrative databases have inherent problems with data collection and coding. Another limitation is that we were unable to address the role of patients’ performance status in perioperative chemotherapy use. Although the diagnoses included in Medicare claims data do allow for an assessment of comorbidity, previous studies indicate that comorbidity may not be associated with performance status.48,49

Our results demonstrated a trend toward the increased use of chemotherapy and combined-modality therapy in elderly patients with resected NSCLC during the decade from 1992 to 2002. The most frequent use of chemotherapeutic agents also changed. Our analysis assessed practice patterns that existed before the publication of a large clinical trial that confirmed the survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy. Consequently, the proportion of patients receiving chemotherapy today may be higher. Better understanding of the biology of lung cancer, the introduction of less toxic regimens, and better supportive care are likely to impact treatment patterns further in elderly patients with NSCLC. Our findings may be used as a baseline against which the benefit of new therapies can be compared.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Branch, Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Science, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Information Services, and the Office of Strategic Planning, Health Care Financing Administration; Information Management Services, Inc; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. Interpretation and reporting of these data are solely the responsibility of the authors. We also thank Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spira A, Ettinger DS. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:379–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Immerman SC, Vanecko RM, Fry WA, Head LR, Shields TW. Site of recurrence in patients with stages I and II carcinoma of the lung resected for cure. Ann Thorac Surg. 1981;32:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosell R, Felip E, Maestre J, et al. The role of chemotherapy in early non-small-cell lung cancer management. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(suppl 3):S63–S74. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mountain CF. Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest. 1997;111:1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Chevalier T for the IALT Investigators. Results of the Randomized International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial (IALT) cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CT) versus no CT in 1867 patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:Abstract 6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:351–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winton TL, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. Vinorelbine and cisplatin vs observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–2597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss GM, Herndon JE, Maddaus MA, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in stage IB non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): update of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) Protocol 9633 [abstract] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006;24:365. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douillard J, Rosell R, Delena M, et al. ANITA: phase III adjuvant vinorelbine (N) and cisplatin (P) versus observation (OBS) in completely resected (stage I–III) non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (pts); final results after 70-month median follow-up [abstract] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;24:619. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scagliotti GV, Fossati R, Torri V, et al. Randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage I, II, or IIIA non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1453–1461. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waller D, Peake MD, Stephens RJ, et al. Chemotherapy for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the surgical setting of the Big Lung Trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tada H, Tsuchiya R, Ichinose Y, et al. A randomized trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone for completely resected pN2 non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG9304) Lung Cancer. 2004;43:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller SM, Adak S, Wagner H, et al. A randomized trial of postoperative adjuvant therapy in patients with completely resected stage II or IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1217–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010263431703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Humble CG, Key CR, Samet JM. Cancer treatment protocols. Who gets chosen? Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2258–2260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde CN, et al. Linking physician characteristics and Medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40(8 suppl):IV-82–IV-95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackillop WJ, O’Sullivan B, Ward GK. Non-small cell lung cancer: how oncologists want to be treated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:929–934. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer MJ, O’Sullivan B, Steele R, Mackillop WJ. Controversies in the management of non-small cell lung cancer: the results of an expert surrogate study. Radiother Oncol. 1990;19:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(90)90162-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greco FA, Hainsworth JD. Paclitaxel-based therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: improved third generation chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(suppl 5):S63–S67. doi: 10.1093/annonc/10.suppl_5.s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greco FA, Burris HA, 3rd, Gray JR, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin adjuvant therapy alone or with radiotherapy for resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: a feasibility study of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. Cancer. 2001;92:2142–2147. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2142::aid-cncr1556>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Cure me even if it kills me: preferences for invasive cancer treatment. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:614–619. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer CJ, Moughan J, Movsas B, et al. Patterns of care survey (PCS) in lung cancer: how well does current U.S practice with chemotherapy in the non-metastatic setting follow the literature? Lung Cancer. 2005;48:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien CR, Lai MS. Trends in the pattern of care for lung cancer and their correlation with new clinical evidence: experiences in a university-affiliated medical center. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21:408–414. doi: 10.1177/1062860606292863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmud SM, Reilly M, Comber H. Patterns of initial management of lung cancer in the Republic of Ireland: a population-based observational study. Lung Cancer. 2003;41:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logan DM, Lochrin CA, Darling G, Eady A, Newman TE, Evans WK. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy for stage II or IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer after complete resection. Provincial Lung Cancer Disease Site Group. Cancer Prev Control. 1997;1:366–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choong NW, Vokes EE. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7(suppl 3):S98–S104. doi: 10.3816/clc.2005.s.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JS, Eraut D, Trask C, Davision AG. Age and treatment of lung cancer. Thorax. 1996;51:564–568. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.6.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Rijke JM, Schouten LJ, ten Velde GP, et al. Influence of age, comorbidity and performance status on the choice of treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer; results of a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Earle CC, Venditti LN, Neumann PJ, et al. Who gets chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer? Chest. 2000;117:1239–1246. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Determinants of cancer therapy in elderly patients. Cancer. 1993;72:594–601. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<594::aid-cncr2820720243>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. A population-based study of functional status and social support networks of elderly patients newly diagnosed with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:366–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Key CR, Samet JM. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;258:3125–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stiggelbout AM, Jansen SJ, Otten W, Baas-Thijssen MC, van Slooten H, van de Velde CJ. How important is the opinion of significant others to cancer patients’ adjuvant chemotherapy decision-making? Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Earle CC, Neumann PJ, Gelber RD, Weinstein MC, Weeks JC. Impact of referral patterns on the use of chemotherapy for lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1786–1792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo R, Giordano SH, Freeman JL, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Referral to medical oncology: a crucial step in the treatment of older patients with stage III colon cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11:1025–1033. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-9-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo R, Giordano SH, Zhang DD, Freeman J, Goodwin JS. The role of the surgeon in whether patients with lymph node-positive colon cancer see a medical oncologist. Cancer. 2007;109:975–982. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gridelli C, Perrone F, Monfardini S. Lung cancer in the elderly. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2313–2314. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosell R, Gatzemeier U, Betticher DC, et al. Phase III randomised trial comparing paclitaxel/carboplatin versus paclitaxel/cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a cooperative multinational trial. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1539–1549. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lokich J, Anderson N. Carboplatin versus cisplatin in solid tumors: an analysis of the literature. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:13–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008215213739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of 4 chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon GR, Bunn PA., Jr Taxanes in the treatment of advanced (stage III and IV) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): recent developments. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:87–104. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120005919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramalingam S, Belani CP. Taxanes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:1693–1709. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.12.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pepe C, Hasan B, Winton TL, et al. National Cancer Institute of Canada, Intergroup Study JBR.10. Adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin in elderly patients: National Cancer Institute of Canada and Intergroup Study JBR. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1553–1561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2750–2756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, Parr J, Balducci L. Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1582–1587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Repetto L, Venturino A, Vercelli M, et al. Performance status and comorbidity in elderly cancer patients compared with young patients with neoplasia and elderly patients without neoplastic conditions. Cancer. 1998;82:760–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]